Abstract

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is used to asses the hydrodynamic performance of a positive displacement left ventricular assist device. The computational model uses implicit large eddy simulation direct resolution of the chamber compression and modeled valve closure to reproduce the in vitro results. The computations are validated through comparisons with experimental particle image velocimetry (PIV) data. Qualitative comparisons of flow patterns, velocity fields, and wall-shear rates demonstrate a high level of agreement between the computations and experiments. Quantitatively, the PIV and CFD show similar probed velocity histories, closely matching jet velocities and comparable wall-strain rates. Overall, it has been shown that CFD can provide detailed flow field and wall-strain rate data, which is important in evaluating blood pump performance.

1 Introduction

The 70 cc pneumatic Penn State University left ventricular assist device (LVAD) received FDA approval for bridge-to-transplant use in 1985 [1]. A completely implantable version of the 70cc LVAD, dubbed the “LionHeart,” has since been developed. This device removed the external leads present in the pneumatic device and relied on an electrically driven pusher plate to achieve the compression [2, 3]. The 70 cc device was designed by in vitro and in vivo techniques without using computational fluid dynamics (CFD).

The 70 cc pump has performed well hemodynamically with the explanted device from animals and patients generally being free of thrombus. Several fluid dynamic factors are believed to contribute to the pump’s satisfactory hemodynamic performance including low turbulent stresses within the chamber [4], wall-shear stresses high enough during the cycle to promote wall washing [5], and no regions of flow stasis [6]. A single wall-washing recirculation was observed during diastole, which served to deter thrombus formation and deposition. This rotational pattern was dependent on both the sac motion and inlet port jet formed during early diastole [5, 7–9]. Dye injection showed that washout occurred within one or two beats, indicating no regions of sustained flow stagnation within the 70 cc device [6].

The 70 cc LVAD was developed for use in a patient population exceeding a bodyweight of 70 kg, restricting use in small adults and children [3]. Several programs related to device scaling are ongoing at the Pennsylvania State University. One program is working to develop a scaled pneumatic device for pediatric applications (PVAD). A second program aims at a fully implantable electric 50 cc device for small adults and adolescents. Scaled-down devices have been prone to thrombus formation during animal testing [10–13]. It has been hypothesized that the increased level of thrombosis is related to changes in the flow field when scaling down from the 70 cc device. It is known that low wall-shear stresses and high residence times influence thrombus formation and deposition within artificial blood pumps [6, 10, 14, 15]. In addition, high fluid shear, turbulence, and regurgitant jets near the mechanical heart valves can cause blood element activation and damage, initiating the clotting cascade [16, 17].

Most of the work to date on the Penn State devices involved experimental based fluid dynamics. Hochareon et al. [5, 7, 9] performed a series of particle image velocimetry (PIV) studies on the 50 cc Penn State LVAD, obtaining both velocity and wall-shear measurements. Hochareon et al. [5, 13] refined the estimation of the wall location and the position of the velocity vector in the irregular measurement volumes nearest the walls to estimate the wall-shear stresses from the PIV measurements. The authors observed regions of low shear rate and flow stasis correlating to areas of in vivo thrombus formation. It was postulated that platelets, having been activated by the high shear stresses found in the vicinity of the mitral valve, aggregate and adhere in areas of the chamber that do not receive adequate wall washing, i.e., regions of low wall-shear or flow stagnation.

Kreider et al. [18] studied the effects of mitral valve orientation on the flow field within the 50 cc Penn State LVAD. Experiments were performed in the mock circulatory pump loop, with the mitral valve at 0 deg, 15 deg, 30 deg, and 45 deg orientations. PIV measurements were taken at planes parallel to the piston, located between 3 mm and 8 mm from the stationary front face, opposite the piston. Mitral valve orientation was found to influence the inlet jet formed during diastole. The most intense and longest duration wall washing was found to occur at a mitral valve orientation of 45 deg, where the flow was directed between the mitral port side wall and the stationary front wall.

Oley et al. [19] used the PIV measurements to assess the off-design performance of the 50 cc Penn State LVAD. Higher beat rates and increased systolic duration were found to behave in a similar manner, showing improved mitral jet penetration and increased wall washing. However, increased wall washing at the top of the chamber was associated with a larger separation near the aortic valve minor orifice. Additionally, it was shown that the Bjork–Shiley valves being used were not optimal for the device.

Computational analysis is playing an increased role in the development and evaluation of heart assist pumps. Detailed experimental measurements require optical access, which can be restricted by components such as the valves. The need for optical access also necessitates the use of a blood analog fluid for many experiments. Important quantities, such as the wall-shear stresses, can be difficult to measure in vitro. CFD can provide more detailed flow field data than either bench top or animal experiments. Detailed in vitro data are often restricted to a few selected region of interest in the device while in vivo experiments yield minimal flow field details.

CFD is useful for predicting the three-dimensional velocities and wall-shear rates through the entire device. However, care must be taken that the computational model adequately reproduces the device behavior. This requires high fidelity simulations, physically realistic models, and validated methodologies. Analysis of a positive displacement LVAD requires resolving/modeling the chamber compression, valve closure, and near-transitional flow regimes. Also, the device thrombotic performance is difficult to assess computationally due to the limited understanding of the relationship between the flow field and the clotting process.

A wide range of computational techniques, useful for modeling positive displacement LVADs, can be found in the literature. To date, however, only a minimal amount of validation has been performed on these models.

Avrahami et al. [20–22] performed an unsteady 3D analysis of a complete pumping cycle for several LVADs. The analysis assumed incompressible, Newtonian, and laminar fluid behaviors. Experimental measurements supplied the inflow and outflow boundary conditions and served as validation for the computational model. The number of nodes for the 3D meshes varied between 10,000 and 50,000. The LVAD contained dual pusher plates acting on opposing faces of the chamber. The wall motion, due to the device pumping, was simulated by moving the front and back circular walls to expand and contract the device volume. Both prescribed chamber motion and fluid-structure interaction (FSI) calculations were included. The valve leaflets were gridded as fully opened and closure was modeled by locally increasing the fluid viscosity.

Stijnen [23, 24] performed computations of a simplified 3D heart model, a 2D moving valve, and a 2D VAD with moving valves. The fictitious domain method, which allows coupling of solid object velocities to fluid velocities, was used to model the fluid-structure interactions of the devices. Valve closure was modeled using both a fictitious domain method and a viscosity valve closure model. Stijnen’s investigations primarily focused on the effects of valve orientation, motion, and interaction. The computational velocities for the 3D heart and 2D valve studies were compared with in vitro data.

Medvitz et al. [25] performed a CFD analysis on the 50 cc Penn State positive displacement LVAD. Both steady-flow and pulsatile-flow conditions were simulated and velocity fields were compared against in vitro PIV measurements. Pulsatile-flow simulations applied a time varying velocity at the piston face to model the chamber compression and a viscosity valve closure model to model the valve effects. Wall-stain rates were also computed from the CFD results.

Medvitz [26] used in vitro PIV velocity and wall-strain rate measurements to validate CFD results of the 50 cc Penn State LVAD. The CFD results compared well against in vitro measurements, demonstrating similar mitral jet and chamber rotational patterns and closely matching velocity magnitudes. Wall-strain rate comparisons showed greater variations but were considered acceptable based on the large experimental and computational uncertainties in predicting wall shear. An empirical metric relating wall-shear rate to thrombus deposition was developed and used to quantitatively compare the geometric variants. Hubbell and McIntire [27] showed that thrombus deposition decreased on polyurethane when the wall-strain rate was raised above 500 s−1. The device thrombotic performance is assessed using this criterion along with the wall-strain histories [26].

Medvitz [26] then used the validated computations along with the empirical thrombus criterion to study geometric scaling, design variants, and valve type. A scaling analysis demonstrated which device geometric and flow field parameters were important for device scaling. The CFD results showed that maintaining Reynolds and Strouhal numbers when geometrically scaling from the 70 cc to the 50 cc device resulted in a less thrombogenic chamber flow. Design comparisons indicated that the addition of a curved front face to the chamber design increased the potential thrombus formation of the modified device. Finally, the use of Bjork–Shiley monostrut valves in the mitral port yielded increased wall washing within the device.

The objective of this work is to validate a computational model thereby demonstrating that CFD is a useful tool for predicting pulsatile LVAD performance. In particular, difficult to measure quantities such as wall-strain rates and three-dimensional velocities are readily obtained using CFD. Also, it will be shown that the valve, piston, Newtonian fluid, and turbulence models are appropriate for use as an engineering design tool.

In this work, the 50 cc Penn State positive displacement LVAD is analyzed computationally. The computations are performed using an implicit large eddy simulation (LES) turbulence approach, dynamic mesh motion for chamber compression, and a viscosity valve closure model. The CFD results are then validated against in vitro PIV measurements. Validation includes qualitative comparisons of the flow patterns, velocity fields, and wall-strain rates. To the best of the author’s knowledge, the comparison of the local CFD and in vitro wall-strain rates is the first of its kind for a blood pump. Once validated, the CFD results can then be used to study design variants, vary operating conditions, and relate the device fluid dynamics (i.e., wall-shear rate) to thrombus deposition [26].

2 Methods

2.1 Model Geometry

The 50 cc Penn State LVAD is a pusher-plate driven positive displacement type pump containing two Bjork–Shiley monostrut valves [23 mm mitral and 21 mm aortic). The valves have a 70 deg maximum opening angle. For this analysis, the mitral valve has a 30 deg orientation while the aortic valve has a 0 deg orientation. The 0 deg orientation is defined such that the valve leaflet pivot axis is perpendicular to the pusher-plate face and flow is directed toward the outer walls. The mitral valve angle (ϕ) is shown in Fig. 1, where the valve is at a 30 deg orientation.

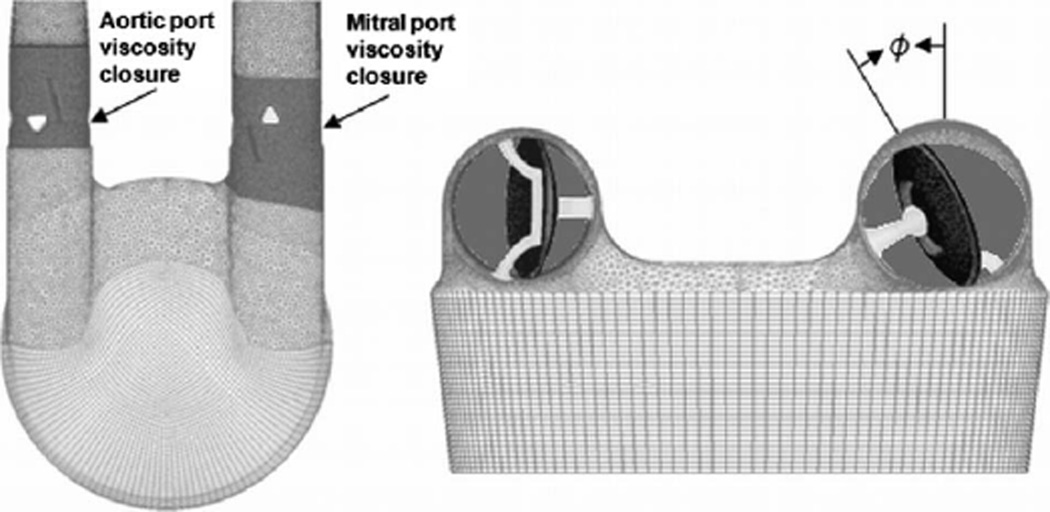

Fig. 1.

Computational mesh used for the analysis of the 50 cc LVAD. Grid includes Bjork–Shiley monostrut valves with support struts. The figure shows the definition of the valve orientation angle along with the regions where the valve viscosity closure model was applied.

The LVAD chamber is 18.8 mm thick and the pusher plate is 6.35 mm in diameter. The stroke length and beat rate determine the flow rate through each device, with the stroke length nominally being 15 mm, yielding a device volume displacement of approximately 50 cc. A thin polyurethane blood sac inserted into the chamber acts as the blood contacting surface and isolates the blood from the mechanical components of the device. In vitro experiments attach a clear acrylic model to a mock circulatory loop [5, 7–9, 18]. The acrylic model is sealed at the piston face using a flexible polyurethane insert.

2.2 In Vitro Validation Model

In vitro PIV data are used for computational validation. The experiments are conducted in a mock circulatory loop, first described by Rosenberg et al. [28]. Physiological atrial and aortic compliances are simulated using piston-type compliance chambers. The systemic resistance is simulated by a parallel plate resistor located downstream of the aortic compliance chamber. Finally, the preload to the LVAD chamber is controlled by a reservoir located between the systemic resistance and the atrial compliance.

PIV measurements are used to obtain noninvasive, instantaneous, spatially resolved velocity measurements. The PIV measurements presented here are averaged over 200 pump cycles. The measurements required optical accessibility to the test fluid, necessitating that the in vitro device be modified from the implantable in vivo device. An optically accessible in vitro model, described in detail in Ref. [5], was designed to mimic the in vivo LVAD fluid dynamics. The in vitro test chamber was machined from acrylic and a nontransparent polyurethane diaphragm sealed the pump at the piston. The portion of the model made from acrylic moved very little in the in vivo model, therefore the rigidity of the acrylic is not considered to be an issue. To reduce image distortion, the measurements require that the fluid be optically clear and the index of refraction of the test fluid equal that of the acrylic; therefore, a blood analog fluid of 50% sodium iodide, 34.47% water, 15.5% glycerin, and 0.03% Xanthan Gum by weight is used as the working fluid. This fluid is non-Newtonian, approximating a 40% hematocrit blood sample, with a kinematic viscosity of 4.3 cS at the high shear limit and a refractive index of 1.49, matching that of the acrylic.

2.3 Computational Simulations

Computational analyses are undertaken with the goal of validating a model to predict the flow field over several heart cycles [26]. To model the pump operation, it is important to apply physical models to both the piston motion and valve closure. In the computational model, the flow is driven through the device using the motion of the piston and the valves are modeled as either fully opened or fully closed. The flow pulsatility is developed by the interaction of the valve and piston models. Both the valve and piston models are specified based on in vitro flow rate measurements.

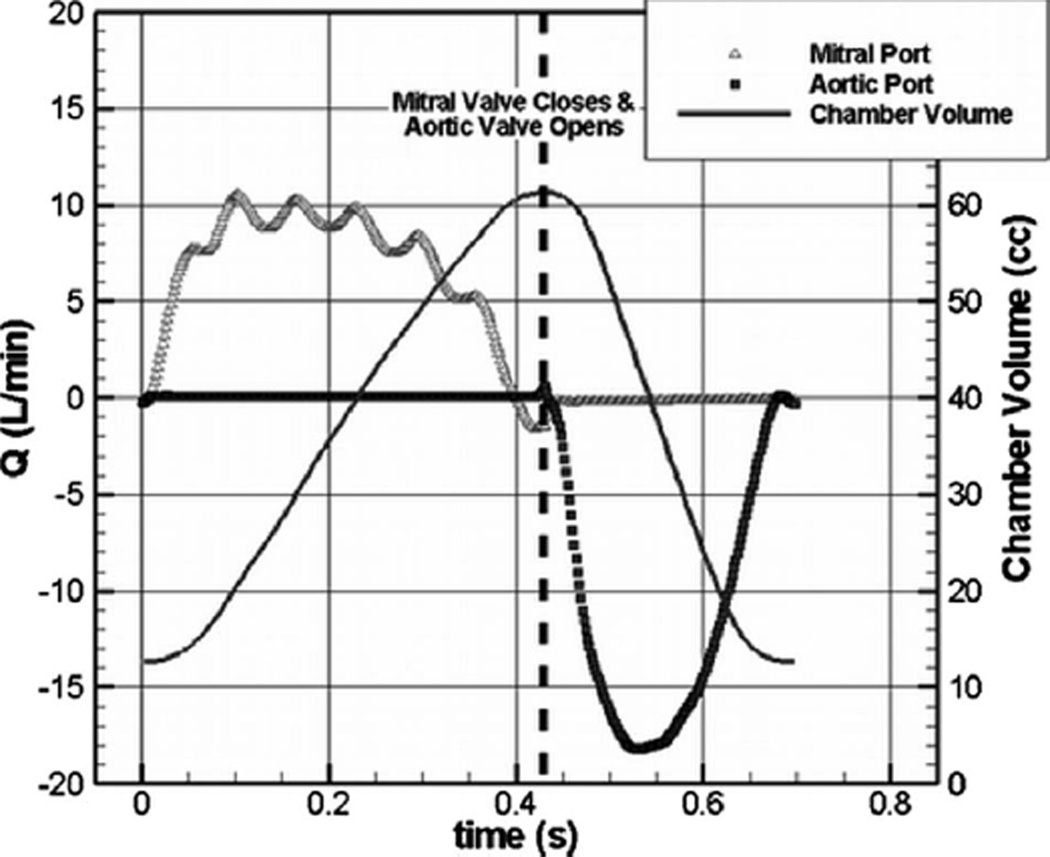

The 50 cc CFD results are validated against in vitro PIV measurements at a device flow rate of 4.2 LPM (liter per minute) at 86 BPM (beats per minute), using a mesh with 3.5×106 grid points and with 400 time steps per cycle (Δt=0.00174 s). A Bjork–Shiley monostrut valve is placed in both ports with the mitral valve angled at a 30 deg orientation. Figure 2 shows the instantaneous chamber volume for one pulse cycle along with the resultant mitral and aortic port volume flow rates. Diastole lasts from the cycle start until 430 ms into the cycle. During diastole, the aortic port flow is negligible and the chamber increases in volume. Systole starts at 430 ms and lasts until 700 ms. During systole, the mitral port flow is negligible and the chamber volume decreases.

Fig. 2.

Instantaneous chamber volume and resultant mitral and aortic port flow rates for the computations of the LVAD operating at 4.2 LPM and 86 BPM

The fluid properties are chosen to match the blood analog fluid used in the in vitro experiments. While the blood analog displays some non-Newtonian characteristics, we assume that these effects are negligible and therefore the fluid is treated as Newtonian in our CFD simulations. The device Reynolds number of 1865 and Strouhal number of 9.0 are computed based on the following equations, which are variations in those used by Bachmann [10] and Deutsch [13]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where SV is the chamber stroke volume, di is the mitral port diameter, N is the beat rate, and R is the ratio of diastolic time to cycle time.

The pulsatile full cycle simulations are computed without a turbulence model via an implicit-LES methodology. This is reasonable based on the low-Reynolds number of the flow and the questionable applicability of most RANS turbulence models near transition. We note that the low-Reynolds number combined with high grid resolution should result in the simulations capturing the larger of the turbulent eddy scales in the unsteady simulations.

2.4 Valve Closure Model

The valves that maintain unidirectional flow must be modeled in a manner that allows proper diastolic and systolic behaviors in the pump. During diastole, blood enters through the mitral port and is stored in the expanding chamber. During systole, blood is ejected from the compressing chamber through the aortic port. Computationally, to account for the valve effects, either the full range of motion of the valves must be included via a dynamically moving mesh or a valve closure model must be used.

For this research, valve closure is modeled using the variable viscosity model employed by Avrahami et al. [20–22] and Stijnen [23, 24]. The valve grids are fixed at the fully opened position for the duration of the analysis. To model valve closure, the fluid viscosity in the ports local to the valves (as shown in Fig. 1) is increased by a multiplier ranging from 5000 to 50,000, resulting in approximately zero velocity through the viscously dominated “closed” valve. This range of multipliers was found to be optimal for both maintaining solution stability and minimizing regurgitant flow. Higher factors reduced the backflow but adversely effected algorithm stability. Lower values resulted in excessive backflow through the closed valve.

The timing of valve opening and closing is based on in vitro flow waveforms and is specified to take on the order of 10 ms. For the case with 400 time steps per beat, closure occurs over 5 time steps (8.7 ms), during which the valve viscosity multiplier is linearly interpolated.

The valve model neglects rebound and leakage as well as the dynamic effects of the valve motion. We assume that the dynamic valve closure effects are of secondary importance to the flow within the chamber, since the duration of opening and closing is short compared with the duration of systole and diastole [23, 24]. Also, the specific aim of the analysis is to evaluate the effects of chamber design on the hemodynamics of the device, assuming the use of a commercial valve, not to design or to optimize an existing valve.

2.5 Chamber Compression Model

The piston motion driving the flow field is modeled using a deforming mesh to displace the piston and vary the chamber volume. A moving mesh model is possible since the piston did not interfere with the mitral or aortic ports. To facilitate the model, the chamber side walls are angled slightly such that the diameter of the bottom face is equal to the piston diameter. To account for the increased displacement volume resulting from compressing the entire angled chamber the stroke length is shortened slightly (by 5–10% depending on the operating conditions) to maintain the correct stroke volume. Previous work has shown that incorporating the grid motion improved the prediction of the mitral jet penetration and the strength of the chamber rotational pattern [26].

The piston is displaced using a time-periodic user defined mesh-displacement function, derived from experimental flow rate measurements. The grid points on the piston are displaced by the full multiplier; the grid points within the chamber are displaced by a linearly decreasing multiplier of the mesh-displacement function, until a location is reached near the stationary chamber face where the mesh is fixed.

A Fourier series of the in vitro flow meter measurements provides a mathematical model of the flow rate, from which the equivalent instantaneous piston velocity is determined. The piston motion is determined by integrating the piston velocity Fourier series, yielding position as a function of time. Describing the piston motion in this manner allows the in vitro flow waveform to be closely reproduced.

2.6 Computational Solver

The computational analyses use an unstructured CFD code to solve the incompressible time accurate conservation of mass and Navier–Stokes equations. ACUSOLVE™ is a finite element CFD solver, which is based on a Galerkin/least-squares formulation, is second-order accurate in space and time and supports a variety of element types [29, 30]. In addition, it uses a fully coupled pressure/velocity iterative solver and a generalized alpha method as a semidiscrete time-stepping algorithm [31]. The solver permits parallel implementation, customized boundary conditions, and contains a native FSI capability along with a discontinuous Galerkin method for sliding mesh simulations.

2.7 Grid Generation

The goals of the grid generation include near-wall resolution able to accurately compute the wall-shear stresses, grid densities able to resolve the larger scales of turbulence, gridding of the fully opened valves, and resolution of the chamber compression. The unstructured mesh used for this analysis contains approximately 3.5×106 points and makes use of tetrahedral, brick, and pyramid elements. A thin layer of brick elements is built near each solid surface using a near-wall spacing of 10−3 in. (25.4 µm), chosen from Kolmogorov length scale approximations. A combination of tetrahedral, brick, and pyramid elements are used to fill the complicated geometry between the wall resolution layers. The occluder, occluder support struts, and outer housing of the Bjork–Shiley valve are included. To facilitate the deforming LVAD chamber, the stroke volume is built exclusively using brick elements. Figure 1 shows the computational mesh for the simulations.

The inlet of the computational domain is located seven diameters upstream of the mitral valve. Because of the aortic valve wake, the outlet is located 15 inlet diameters downstream of the aortic valve, so that the outlet boundary condition is away from the valve induced flow unsteadiness.

2.8 Boundary Conditions

A constant total pressure boundary condition is set at the inflow while a constant static pressure is set at the outlet. In vitro measurements give a device mean static pressure rise of 80 mm Hg with in-cycle fluctuations of ±20 mm Hg. The velocity contribution to the total pressure at the inflow is negligible in comparison to the static pressure contribution, allowing the experimental static pressure to be used as the inflow total pressure boundary condition. For all simulations, the LVAD pressure rise was set to a constant 80 mm Hg. Test simulations, where the pressure fluctuations were added, yielded velocity and strain rate fields virtually indistinguishable from the constant pressure rise condition [26].

2.9 Validation Methods

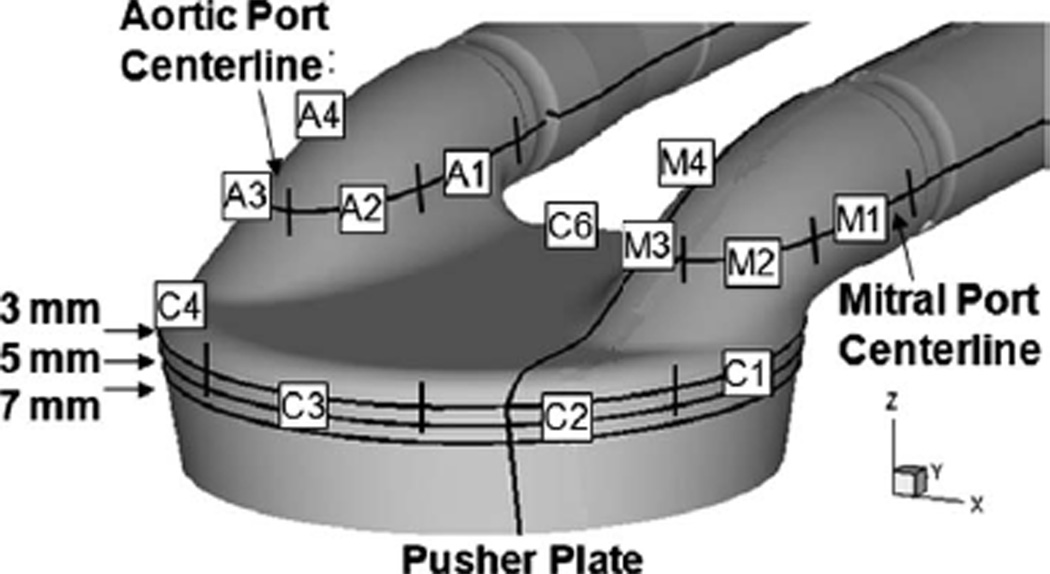

The computational simulations are validated by comparing against two-dimensional in vitro PIV data taken from the 50 cc model. The CFD and PIV data are compared at measurement planes parallel to the pusher plate, at locations ranging from 3 mm to 8 mm from the front stationary face of the LVAD. Additional comparisons are made at the mitral and aortic port centerlines parallel to the pusher plate and in the mitral port perpendicular to the pusher plate. Figure 3 shows the comparison locations. The PIV data contain two in-plane components of velocity averaged over 200 cycles. The CFD results are instantaneous, taken from the third pulse cycle. Choosing the third cycle reduces startup effects while limiting the computational effort. The difference between instantaneous CFD and averaged PIV results is a potential source of error in the validation comparisons.

Fig. 3.

CFD extraction planes located 3 mm, 5 mm, and 7 mm from the front face of the LVAD, at the mitral and aortic port centerlines parallel to the pusher plate, and through the mitral port perpendicular to the pusher plate 5 mm inside of the port centerline. The strain rate extraction arcs for the mitral and aortic ports along with the chamber are labeled.

Wall-strain rates extracted from the PIV and CFD are compared at selected locations in the chamber and ports. Shear rate histories are extracted along surface arcs at the mitral and aortic port centerlines and at the chamber 3 mm plane, parallel to the pusher plate. Figure 3 shows the extraction arcs for the ports and chamber. Each port is broken into four separate segments defined as M1, M2, M3, and M4 for the mitral port and A1, A2, A3, and A4 for the aortic port. Figure 3 also shows the extraction arcs at the 3 mm plane, where the chamber is broken into six arcs (C1–C6], beginning beneath the mitral port. The arc marching direction for each segment is defined as clockwise positive when looking from the stationary face toward the pusher plate. The marching direction is important for defining the sign of the strain rate; near-wall velocity in the same direction as the segment marching gives a positive strain rate, and velocity in the opposite direction gives a negative strain rate.

The PIV strain rate is calculated using high-resolution two-dimensional velocity fields. To account for the irregular PIV interrogation regions close to the walls, a centroid shifting technique described by Hochareon et al. [5, 7] is employed. The postprocessing algorithm determines the wall location and the in-plane velocity component tangential to the wall. The wall-strain rate for the PIV is defined as

| (3) |

where Vt is the wall tangential velocity and dw is the wall normal distance [7]. This methodology has proven highly reliable in regions where the flow is relatively two dimensional but likely underpredicts the wall-shear in highly three-dimensional regions of flow. The computational wall-strain rate for the PIV validation is defined as

| (4) |

where the velocity and coordinates axes are in a rotated coordinate frame aligned with the principal axis.

To preserve two dimensionality, the velocity component through the plane is neglected. The velocity gradient tensor is directly outputted from CFD simulation, and a coordinate rotation is performed to align the velocity gradient tensor with the principle axis.

3 Results

3.1 Velocity Comparisons

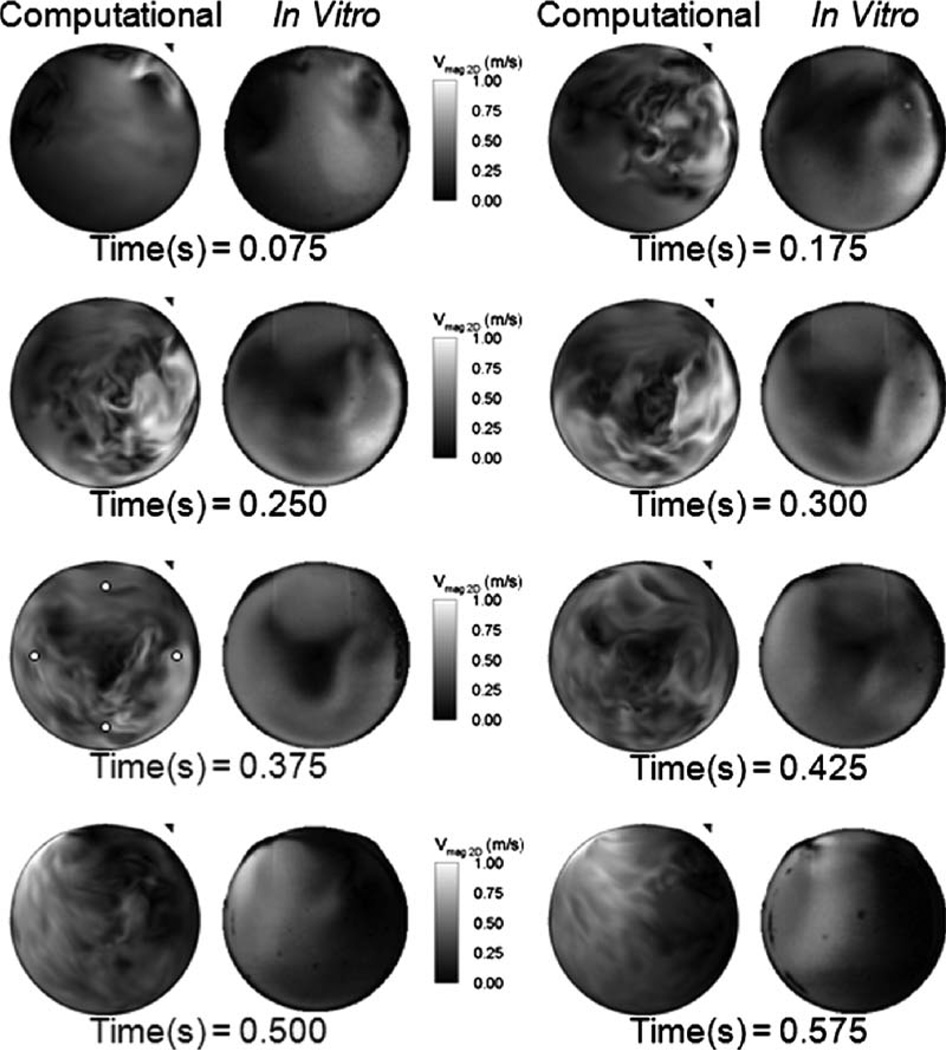

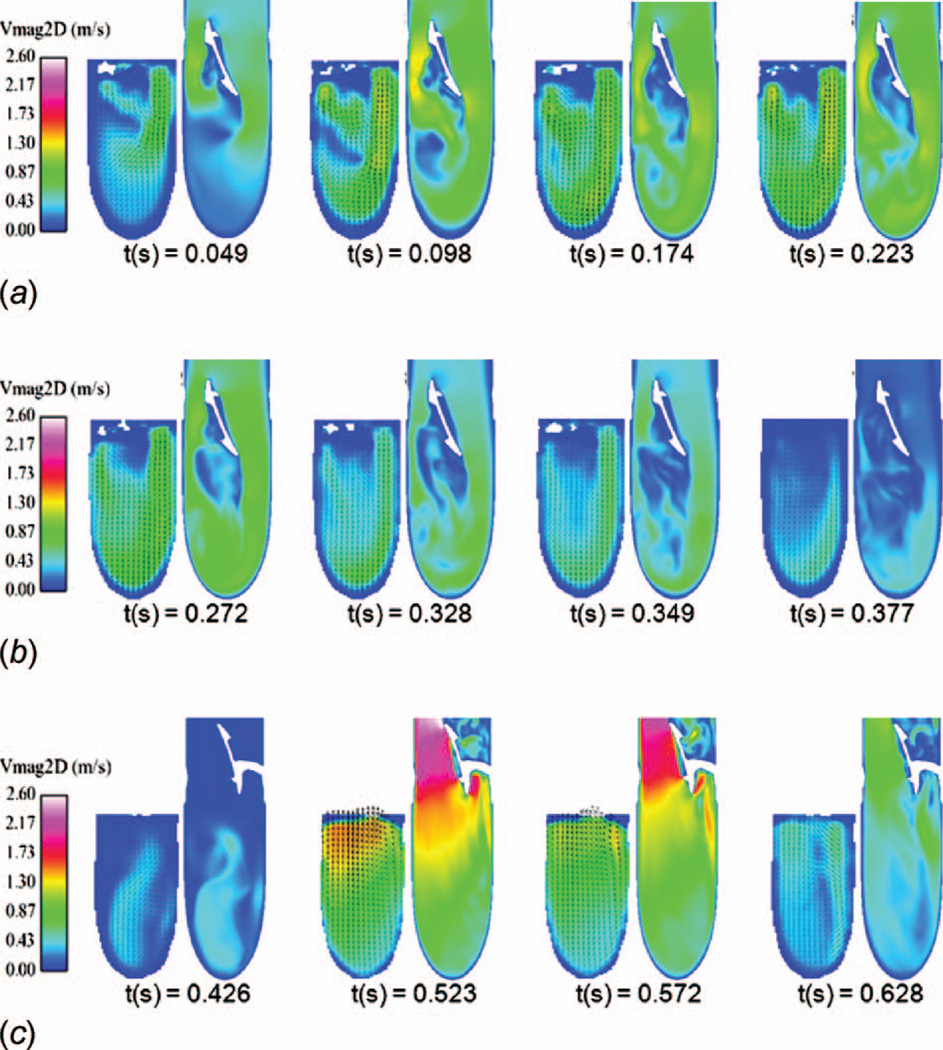

Figure 4 shows the in-plane velocity magnitude contours at the chamber 3 mm location for both the computations and the PIV measurements from early diastole to midsystole. The computations compare reasonably well with the PIV data displaying similar chamber rotational patterns and mitral port jets. The mitral jet peaks at approximately 1 m/s, whereas the PIV peaks at 0.9 m/s for the diastolic times shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Computational and in vitro velocity magnitude contours at the 3 mm plane comparing the CFD against the PIV results at 4.2 LPM and 86 BPM. The 0.375 time step displays the probe locations where PIV and CFD velocity time histories were extracted.

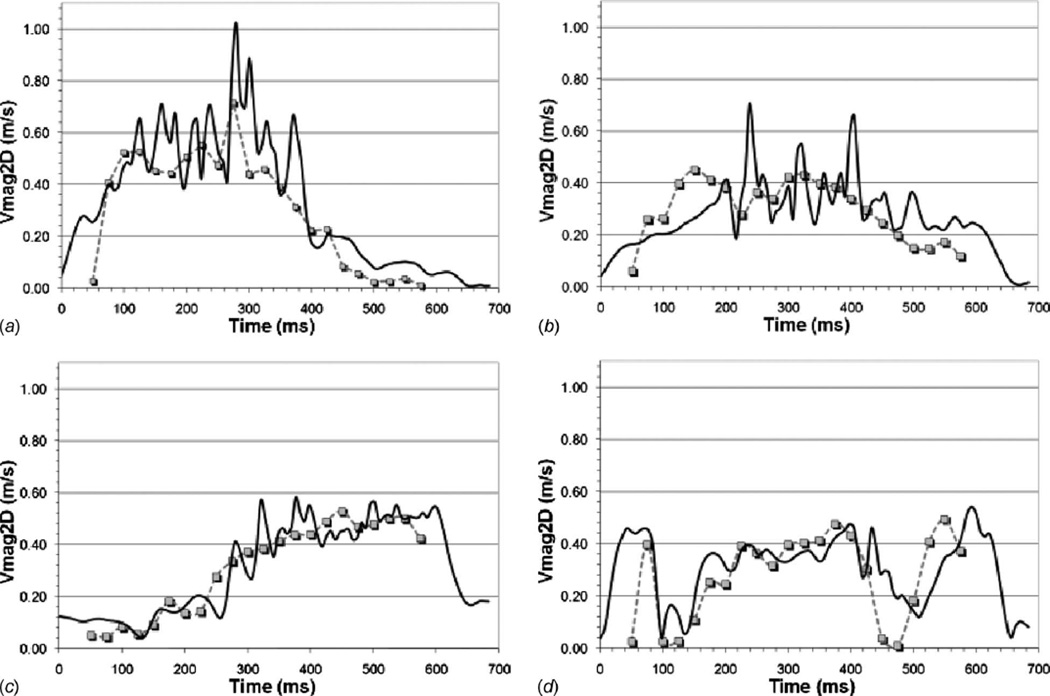

Figure 5 shows a comparison of the PIV and CFD in-plane velocity magnitude at four-probe locations along the chamber 3 mm plane. The probe locations in the chamber were previously shown in Fig. 4 at the 375 ms time step. The probes show that the PIV and CFD velocity time histories closely followed the same trends and are of comparable magnitude. High frequency velocity fluctuations are observed in the CFD results and are likely an artifact of the instantaneous nature of the CFD results, the implicit-LES turbulence methodology, and the significantly higher temporal resolution of the CFD. The comparisons also show that the mitral valve timing, which was inferred from the in vitro flow waveform data, varies slightly between the PIV and CFD. This is evident in Fig. 5 at the beginning and end of the cycle.

Fig. 5.

In vitro and CFD in-plane velocity magnitude comparisons at four points on the 3 mm measurement plane. The symbols show the PIV data and the solid lines the CFD data. The figures correspond to extraction points 75% out from the chamber center at the (a) 3 o’clock, (b) 6 o’clock, (c) 9 o’clock, and (d) 12 o’clock positions, as shown in Fig. 3.

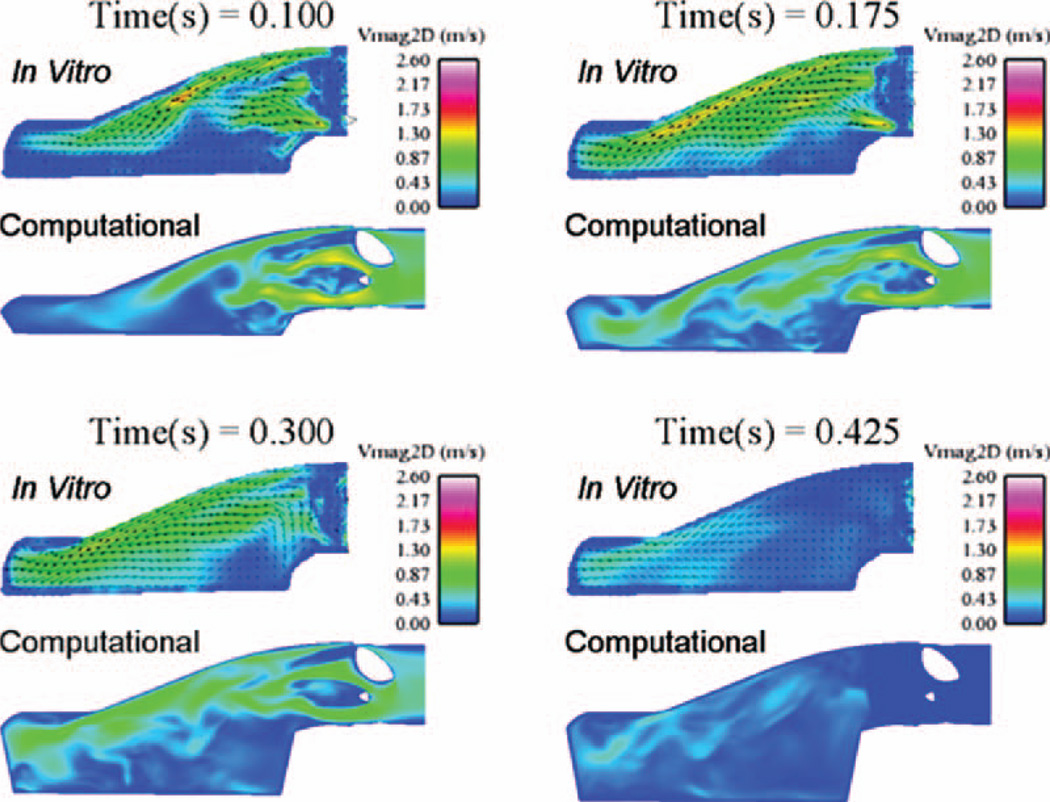

In-plane velocity magnitude contours perpendicular to the piston are shown in Fig. 6, where the piston is at the bottom of the images. The measurement plane is located 5 mm inside the mitral port centerline, as shown in Fig. 3. It should be noted that the PIV measurements are unavailable within the lower portion of the chamber due to a loss of optical access caused by the polyurethane diaphragm. The PIV results are taken downstream of the valve only, whereas the valve and support struts are visible in the CFD results.

Fig. 6.

Computational and in vitro in-plane velocity magnitude contours at a plane 5 mm to the inside of the mitral port centerline

During early and mid-diastole, three jets are observed in both the CFD and PIV measurements. The jets are caused by flow accelerating between the outer port walls, valve leaflet, and valve support struts. Regions of low flow are observed in the chamber directly under the port where the device geometry results in a separated flow region. During late diastole, the velocity in the plane decreases substantially and by systole (flow images for systole not shown) the in-plane flow is negligibly small.

Figure 7 shows the in-plane velocity magnitude contours at the centerline of the mitral and aortic ports, in a plane parallel to the pusher plate. The CFD results are compared against the PIV measurements. The valve leaflet is readily observable in the CFD results, although the near valve model does not capture the valve’s opening and closing phases. The valves and near valve flow are not clearly defined in the PIV results, where the laser sheet is blocked by the leaflets.

Fig. 7.

In-plane velocity magnitude contours at a plane through the center of the mitral and aortic ports parallel to the pusher plate. (a) shows the mitral port during early diastole, (b) shows the mitral port during late diastole, and (c) shows the aortic port during systole. The left image for each port and time step shows the in vitro results while the right image shows the CFD results.

Figure 7 (a) shows the mitral port flow field during early diastole. Two jets develop during this period through the mitral valve’s major and minor orifices and increase in strength with time. A wake forms downstream of the valve and is evident in both the PIV and CFD. A low velocity region develops along the inner wall of the mitral port, downstream of the minor orifice beginning at a time of 0.049 s and continuing through early diastole. The CFD captures the flow field details observed in the PIV, such as the jets and separations, to a high degree of fidelity. During both early and late diastoles, the flow in the aortic port was negligible.

Figure 7 (b) shows the mitral port during late diastole as the jet strength progressively weakens. The separation emanating from the mitral valve leaflet grows in length, and a weak flow begins to develop in the aortic port, despite the aortic valve remaining closed.

Figure 7 (c) shows the aortic port flow field during systole. A strong major orifice jet and a weaker minor orifice jet form in the aortic port. The peak systolic jets through the aortic port are much stronger than the peak diastolic jets in the mitral port, suggesting that the aortic port should experience higher wall shear. High velocity jets through the aortic valve major orifice along with the wake behind the aortic minor orifice support strut are readily observable in the CFD. Flow in the mitral port is very low during systole.

3.2 Wall-Strain Rate Comparisons

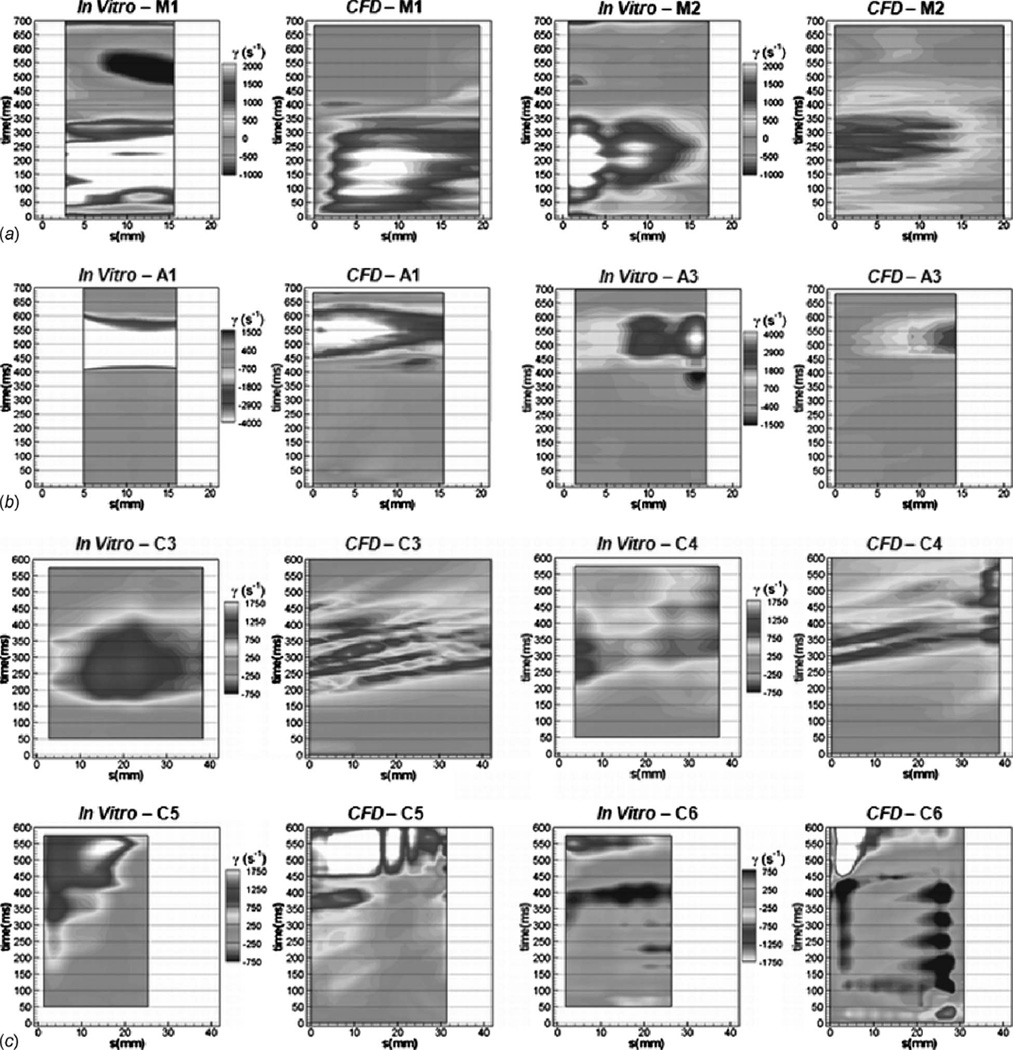

Figure 8 shows the two-dimensional wall-strain rate histories for the mitral and aortic port centerlines along with the chamber’s 3 mm plane. The methodology for developing the strain rate histories was previously described. The extractions are taken along the arcs defined in Fig. 3. The figures show the PIV data and the 2D CFD strain as defined by Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively.

Fig. 8.

Wall-strain rate histories showing in vitro and computational results in (a) the mitral port M1 and M2 locations, (b) the aortic port A1 and A3 locations, and (c) the chamber C3–C6 locations

Figures 8(a) and 8(b) show the wall-strain rate histories for the centerline of the mitral and aortic ports, respectively. The highest shear rates in the device are observed in the aortic port during systole, for both the PIV and CFD. The PIV and CFD strain rates compare well at most locations in the mitral and aortic ports.

The mitral port exhibits time dependent fluctuations in strain rate not observed in the PIV data. This is likely due to flow unsteadiness at the inside of the mitral port caused by the flow expanding from the port into the chamber. In this case, phase averaging of the CFD solution would likely reduce the fluctuations. No fluctuations are observed in the aortic port, where the flow is constricted and accelerated as it entered the port from the chamber.

The 2D computational shear rate maps demonstrate a reasonable resemblance to the PIV maps within the mitral and aortic ports. Because of the nature of the valve model, the CFD results tend to miss the regurgitant flow visible in the PIV measurements. This is most evident at the outer walls of the device; the M1 and M2 locations in the mitral port during systole (500 ms) and the A3 and A4 (not shown) locations in the aortic port during late diastole (350 ms).

Figure 8 (c) shows the chamber wall-strain rate comparisons at the C3–C6 locations. The C1 and C2 planes were also analyzed and are summarized in Ref. [26]. At the C1 location, both the PIV and CFD display very low strain rates throughout the cycle. Both the PIV and CFD show a peak wall-strain rate of approximately 1700 s−1 at C2.

Figure 8(c) shows the C3 plane has a peak CFD shear of 1550 s−1 and a peak PIV wall shear of 1320 s−1. The peaks occur 300 ms into the cycle. The location displays a similar trend between the PIV and CFD. The CFD exhibits strain rate fluctuations not occurring in the PIV data. The temporal resolution is much higher for the CFD data; the PIV is obtained in 25 ms increments while CFD results are available every 1.75 ms. The higher temporal resolution of the CFD along with the comparison of instantaneous CFD against 200 beat averaged PIV are the likely contributors to fluctuations appearing in the CFD but not in the PIV strain rates in both the chamber and the ports.

The C4 and C5 arcs are located between the 7 o’clock and 11 o’clock positions on the aortic port side of the chamber. The C4 arc shows very similar trends between the PIV and CFD, both in shape and magnitude. The peaks at the C4 plane are 1650 s−1 for the CFD and 1150 s−1 for the PIV. At the C5 arc, the strain rate follows very similar trends, although the CFD predicts higher levels of strain, 3000 s−1 peak against 2100 s−1 for the PIV.

The chamber C6 arc is located between the ports. It should be noted that the contour levels of C6 are reversed from the other chamber arcs. At the C1–C5 arcs, the nominal chamber flow direction is consistent with the arc marching direction, whereas the nominal flow direction is opposite the arc marching direction for the C6 arc. Comparing the PIV and CFD, the C6 arc shows similar trends. The CFD consistently predicts higher levels of strain, and the peak CFD strains are more than twice the peak PIV strains. Similar fluctuations are observed in both CFD and PIV between 150 ms and 400 ms.

4 Discussion

The objective of this work was to validate a computational methodology for predicting the detailed flow field through a positive displacement LVAD. In this work, the CFD results are compared against in vitro data as a means of computational validation. Both in-plane velocity magnitudes and two-dimensional wall-strain rates in the ports and chamber are compared.

The computed velocities within the chamber were found to agree well with the experimental predictions. The largest observed differences were the fluctuations present in the instantaneous CFD results, which were absent from the averaged PIV results. However, the bulk CFD flow patterns closely resembled the in vitro chamber flow. In the future, to improve comparisons, it would be desirable to average the computational results in a manner similar to that of the PIV measurements.

The velocity magnitude contours through the ports match very closely between the CFD and PIV throughout the cycle. Minimal differences are observed between the averaged PIV and the instantaneous CFD, due to the high velocity jet nature of the flow through the ports, which damps the unsteady fluctuations within the ports.

The CFD wall-shear rates are in general found to compare well with the PIV data in both contour shape and magnitude range. This is particularly encouraging given the high level of uncertainty inherent to the measurement of local wall-strain rate using PIV and the effects of low-Reynolds number turbulence on the CFD wall strains. Within the chamber, the CFD is found to consistently predict a larger value of wall shear than the PIV data. Within the mitral and aortic ports, the CFD predicts a consistently lower level of wall shear than the PIV data. It should be noted that the chamber PIV resolution (85 µm/pixel) is lower than the ports (50 µm/pixel), increasing the uncertainty of the in vitro chamber measurements. Despite the uncertainties, the comparisons seem to indicate that CFD can provide wall-strain rate estimates useful needed for design guidance.

A discrete method was used to model the valve closure, where the valves were gridded and fixed as fully opened and the local fluid viscosity was increased to “shut off” the flow through the valves. Based on the validation results, this model was deemed adequate to capture the chamber flow patterns critical to thrombus formation. However, near valve effects, critical to platelet activation and possibly hemolysis, were ignored. The compressing mesh piston model was implemented to reproduce the in vitro device flow waveform. The compressing mesh model was found to accurately reproduce the chamber flow patterns and the resolution of the piston motion was deemed an essential capability of the model. Future improvements can be made to the CFD model by eliminating the simplifications of the current valve and piston models, allowing the in vitro motion of the valves and chamber to be captured.

The implicit-LES model proved reliable for predicting the low-Reynolds number flows within the LVAD. In the future, increased mesh resolution would be useful to capture a larger range of the turbulent eddies. Measurements in the 70 cc device [4] and estimates based on computations of the 50 cc device [26] have found the Kolmogorov length scale to be on the order of 0.001 in. (25.4 µm). This resolution was achieved for only the near-wall regions in the current simulation. Increased mesh refinement along with the computing of more cycles for statistical purposes would increase the accuracy when determining the Reynolds stresses. Also, the effects of implicit-LES modeling compared with LES, direct numerical simulation (DNS), and Reynolds averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) models should be investigated.

Finally, the working fluid should in the future be treated as non-Newtonian in the computations to give better insight into the device operation in clinical applications.

5 Conclusions

This work established a computational model for use on a positive displacement LVAD, producing an accurate reproduction of the device in vitro flow field. This model was validated against in vitro PIV measurements of both flow velocities and wall-strain rates. The validation comparisons demonstrate that despite simplifications made to the CFD model, such as the valve, piston, and implicit-LES models, physically realistic results can be obtained for both velocity and wall-strain rates. In general, the CFD compared well against the measurements, demonstrating similar mitral jet strengths and distributions, and establishing a similar rotational pattern within the chamber during mid- to late diastole and early systole. The wall-strain rate measurements also compared well between the CFD and PIV considering the high level of uncertainty in those comparisons. The valve model, piston model, implicit-LES model, and Newtonian fluid assumption were justified based on the validation comparisons. Validation of the CFD methodology established that the model was adequate to provide device design guidance. The quality of the comparisons gives confidence that the CFD results can be extended to obtain flow details, which are not readily available in vitro, such as the through plane velocity and the wall-strain rate field over the entire device. Based on the quality of the validation data, it is possible to extend the analysis to simulate operating conditions where experimental data are not available.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through Grant No. 2 R01 HL060276-08A1.

Contributor Information

Richard B. Medvitz, Email: rbm120@psu.edu, Applied Research Laboratory, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802.

Varun Reddy, Department of Bioengineering, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802.

Steve Deutsch, Applied Research Laboratory and Department of Bioengineering, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802.

Keefe B. Manning, Department of Bioengineering, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802

Eric G. Paterson, Applied Research Laboratory and Department of Mechanical and Nuclear Engineering, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802

References

- 1.Magovern JA, Pennock JL, Campbell DB, Pae WE, Pierce WS, Waldhausen JA. Bridge to Heart Transplantation: The Penn State Experience. J. Heart Transplant. 1986;5:196–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snyder AJ, Rosenberg G, Weiss WJ, Ford SK, Nazarian RA, Hicks DL, Marlotte JA, Kawaguchi O, Prophet GA, Sapirstein JS. In Vivo Testing of a Completely Implanted Total Artificial Heart System. ASAIO J. 1993;39:M177–M184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta SM, Weiss WJ, Snyder AJ, Prothet GA, Pae WE, Rosenberg G, Pierce WS. Testing of a 50 cc Stroke Volume Completely Implantable Artificial Heart: Expanding Chronic Mechanical Circulatory Support to Women, Adolescents, and Small Statue Men. ASAIO J. 2000;46:779–782. doi: 10.1097/00002480-200011000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin JT, Deutsch S, Geselowitz DB, Tarbel JM. LDA Measurements of Mean Velocity and Reynolds Stress Fields Within an Artificial Heart Ventricle. ASME J. Biomech. Eng. 1994;116:190–200. doi: 10.1115/1.2895719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hochareon P. Ph.D. thesis. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State Universiy; 2003. Development of Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) for Wall Shear Stress Estimation Within a 50cc Penn State Artificial Heart Ventricular Chamber. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francischelli DE, Tarbell JM, Geselowitz DB. Local Blood Residence Times in the Penn State Artificial Heart. Artif. Organs. 1991;15:218–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1991.tb03042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochareon P, Manning KB, Fontaine AA, Tarbell JM, Deutsch S. Wall Shear-Rate Estimation Within the 50cc Penn State Artificial Heart Using Particle Image Velocimetry. ASME J. Biomech. Eng. 2004;126:430–437. doi: 10.1115/1.1784477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hochareon P, Fontaine AA, Deutsch S, Tarbell JM, Manning KB. Diaphragm Motion Affects Flow Patterns in an Artificial Heart. Artif. Organs. 2003;27(12):1102–1109. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2003.07206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochareon P, Manning KB, Fontaine AA, Tarbell JM, Deutsch S. Fluid Dynamic Analysis of the 50cc Penn State Artificial Heart Under Physiological Operating Conditions Using Particle Image Velocimetry. ASME J. Biomech. Eng. 2004;126:585–593. doi: 10.1115/1.1798056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachmann C, Hugo G, Rosenberg G, Deutsch S, Fontaine AA, Tarbell JM. Fluid Dynamics of a Pediatric Ventricular Assist Device. Artif. Organs. 2000;24(5):362–372. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2000.06536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamanaka H, Rosenberg G. A Multiscale Surface Evaluation of Thrombosis in Left Ventricular Assist Systems. ASAIO J. 2003;49:222. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daily BB, Pettitt TW, Sutera SP, Pierce WS. Pierce-Donarchy Pediatric VAD: Progress in Development. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1996;61:437–443. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00991-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutsch S, Tarbell JM, Manning KB, Rosenberg G, Fontaine AA. Experimental Fluid Mechanics of Pulsatile Artificial Blood Pumps. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2006;38:65–86. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown CH, Leverett LB, Lewis CH. Morphological, Biochemical, and Functional Changes in Human Platelets Subjected to Shear Stress. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1975;86:462–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konig CS, Clark C. Flow Mixing and Fluid Residence Times in a Model of a Ventricular Assist Device. Med. Eng. Phys. 2001;23:99–110. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(01)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoganathan AP, Reul H, Blank MM. Cardiovascular Biomaterials. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1992. Heart Valve Replacements: Problems and Developments; pp. 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu PC, Lau HC, Liu JS. A Reevaluation and Discussion on the Threshold Limit for Hemolysis in a Turbulent Shear Flow. J. Biomech. 2001;34:1361–1364. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreider JW, Manning KB, Oley LA, Fontaine AA, Deutsch S. A Parametric Study of Valve Orientation Flow Dynamics. ASAIO J. 2006;52:123–131. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000199750.89636.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oley LA, Manning KB, Fontaine AA, Deutsch S. Off- Design Considerations of the 50cc Penn State Ventricular Assist Device. Artif. Organs. 2005;29(5):378–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2005.29064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avrahami I. Ph.D. thesis. Tel-Aviv, Israel: Tel-Aviv University; 2003. The Effects of Structure on the Hemodynamics of Artificial Blood Pumps. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avrahami I, Rosenfeld M, Einav S. The Hemodynamics of the Berlin Pulsatile VAD and the Role of Its MHV Configuration. J. Biomed. Eng. 2006;34(9):1373–1388. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avrahami I, Rosenfeld M, Raz S, Einav S. Numerical Model of Flow in a Sac-Type Ventricular Assist Device. Artif. Organs. 2006;30(7):529–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2006.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stijnen J. Ph.D. thesis. Eindhoven, The Netherlands: Eindhoven University; 2004. Interaction Between the Mitral and Aortic Heart Valve: An Experimental and Computational Study. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stijnen J. Evaluation of a Fictitious Domain Method for Predicting Dynamic Response of Mechanical Heart Valves. J. Fluids Struct. 2004;19:835–850. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medvitz RB, Kreider JW, Manning KB, Fontaine AA, Deutsch S, Paterson EG. Development and Validation of a Computational Fluid Dynamics Methodology for Simulation of Pulsatile Left Ventricular Assist Devices. ASAIO J. 2007;53:122–131. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e31802f37dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medvitz RB. Ph.D. thesis. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University; 2008. Development and Validation of a Computational Fluid Dynamic Methodology for Pulsatile Blood Pump Design and Prediction of Thrombus Potential. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hubbell JA, McIntire LV. Visualization and Analysis of Mural Thrombogenesis on Collagen, Polyurethane, and Nylon. Biomaterials. 1986;7:354–363. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(86)90006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg G, Phillips WM, Landis DL, Pierce WS. Design and Evaluation of the Pennsylvania State University Mock Circulatory System. ASAIO J. 1981;4(2):41–49. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shakib F. Ph.D. thesis. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University; 1989. Finite Element Analysis of the Compressible Euler and Navier–Stokes Equations. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes TJR, Shakib F. Computational Aerodynamics and the Finite Element Method; AIAA/AAS Astrodynamics Conference; Jan. 11–15; Reno, NV. 1988. AIAA Paper No. 88-0031. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jansen KE, Whiting C, Hulbert GM. A Generalized-Alpha Method for Integrating the Filtered Navier-Stokes Equations With a Stabilized Finite Element Method. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2000;190:305–319. [Google Scholar]