Abstract

Objective

This study examines whether alcohol use disorder status and consequences of drinking moderate the course of PTSD over the first 6 months following trauma exposure in a sample of female victims of interpersonal violence.

Methods

Female sexual and physical assault victims (n = 64) were recruited through police, hospital, and victim service agencies. Women completed structured clinical interviews and self-report measures within the first five weeks, three months, and six months post-trauma with 73% retention across all three time points (n = 47). Analyses were conducted using Hierarchical Linear Modeling using alcohol abuse/dependence, peak alcohol use, and consequences during the 30 days prior to assault as moderators of the course of PTSD over time.

Results

Women with alcohol use disorder at baseline had lower initial PTSD symptoms but also less symptom recovery over time than women without alcohol use disorder. This pattern of results was also found for those with high negative drinking consequences during the month prior to the assault. Baseline alcohol use was not found to significantly moderate PTSD course over the 6 months.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that negative consequences associated with alcohol use may be a risk factor for PTSD. Incorporating assessment of drinking problems for women presenting early post-trauma may be useful for identifying PTSD risk.

Keywords: PTSD, alcohol abuse, rape, crime victims, comorbidity

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcohol use disorders often co-occur in women (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005; Kessler, Crum, Warner, Nelson, & et al., 1997; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995; Mills, Teeson, Ross, & Peters, 2006; Stewart, Ouimette, & Brown, 2002). Comorbid PTSD and alcohol use disorder are associated with poorer outcomes than the presence of either disorder alone. Specifically, individuals with alcohol use disorder who also meet criteria for PTSD tend to have poorer physical health and more functional impairment than those without PTSD (Back, Sonne, Killeen, Dansky, & Brady, 2003; Kaysen et al., 2006; McFarlane et al., 2009; Ray et al., 2009; Read, Brown, & Kahler, 2004; Riggs, Rukstalis, Volpicelli, Kalmanson, & Foa, 2003; Stewart, Conrod, Pihl, & Dongier, 1999). However, many of these studies have been conducted in cross-sectional samples. Thus, they cannot evaluate whether those with alcohol use disorder are prospectively more likely to develop more severe PTSD symptoms following trauma exposure or are at greater risk of chronicity. Using a longitudinal design, the current study examined the impact of alcohol misuse on the course of PTSD in women who experienced recent trauma.

PTSD is often conceptualized as a failure of natural recovery (e.g., Foa, Huppert, & Cahill, 2006; Foa & Rothbaum, 1998). According to this conceptualization, trauma-related symptoms are common in the immediate aftermath of trauma and represent a non-pathological response and adaptation to extremely stressful events. Although these symptoms tend to abate for most trauma-exposed individuals over time, it is suggested that they persist in others, ultimately leading to a diagnosis of PTSD. Consistent with this conceptualization, symptoms of PTSD are commonly reported in the weeks immediately following trauma, and these symptoms decline over the initial months after trauma exposure for many trauma survivors (e.g., Kessler et al., 1995; Riggs, Rothbaum, & Foa, 1995; Rothbaum, Foa, Riggs, Murdock, & Walsh, 1992). Courses of PTSD include resilience, a delayed course, a chronic course, and one of recovery (Bonanno, 2004; Dickstein et al., 2010; Elliott et. al., 2005; O’Donnell, Elliott, Lau, & Creamer, 2007).

Accordingly, the identification of factors that may interfere with natural recovery and thereby may contribute to the development of PTSD is of critical importance. A number of factors have been found to predict a more chronic course of PTSD, including both trauma characteristics and individual vulnerabilities. Sexual assault, number of prior traumatic events, and younger age at the time of trauma exposure all predict a greater likelihood to develop PTSD (Brewin et al., 2000; Cougle, Resnick & Kilpatrick 2009; Kessler et al., 1995; Kilpatrick & Saunders, 1999; Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2007). In addition, history of prior psychological difficulty has been found to increase vulnerability (Brewin et al., 2000).

The Impact of Alcohol on PTSD

Misuse of alcohol appears to be another factor that may hinder natural recovery and increase the risk of a more chronic course of PTSD (Blanchard et al., 1996; Zlotnick et al., 2004). Alcohol use may interfere with emotional processing of the traumatic event, which is hypothesized to be critically linked to recovery from PTSD symptoms (Foa et al., 2006). Indeed, several studies have found that alcohol use disorders are associated with increased risk of PTSD diagnosis or a more severe and chronic course of symptoms (e.g., Acierno et al., 1999; Blanchard et al., 1996; Conrod & Stewart, 2003; Cottler et al., 1992; Flood, McDevitt-Murphy, Weathers, Eakin, & Benson, 2009; Kessler et al., 2005; Ray et al., 2009; Riggs et al., 2003; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Stazynski, 2006; Zlotnick et al., 2004).

Need for Longitudinal Studies

Despite theories and findings suggesting that alcohol use disorder is associated with a more chronic course of PTSD, only four longitudinal studies have been conducted soon after trauma exposure to examine this relationship (Kaysen et al., 2006; McFarlane et al., 2009; Zatzick et al., 2002, 2006). In a study of female crime victims, Kaysen and colleagues (2006) examined the role of a prior diagnosis of an alcohol use disorder or drinking problems on recovery from PTSD following a physical or sexual assault. A lifetime history of prior alcohol problems was associated with more severe initial PTSD. Moreover, although PTSD symptoms improved from one month to three months post-assault, women with alcohol problems remained more symptomatic at three months than women without a history of alcohol problems. However, the ultimate implications of the study findings are unclear given limitations in the measurement of alcohol-related variables. Specifically, only lifetime history of alcohol use disorder and alcohol problems was measured, and variables related to alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol use disorder diagnoses at the time of the assault were not measured.

In a second longitudinal study, McFarlane and colleagues (2009) assessed trauma-related symptoms, alcohol use, and alcohol-related consequences at the time of initial hospitalization and three months later in individuals who experienced a traumatic injury. Traumatic injury was defined as any injury that required a hospital admission of greater than twenty-four hours. Moderate alcohol consumption before and after trauma exposure was associated with lower PTSD symptoms, whereas those with problematic drinking endorsed higher PTSD symptoms immediately after trauma exposure. Similarly, individuals reporting drinking problems three months after trauma exposure had higher PTSD symptom severity than abstainers or moderate drinkers.

Although these two studies differed substantially with respect to sample, design, and measurement of alcohol-related variables, their findings suggest that problematic alcohol use is associated with greater severity of PTSD over time. However, because each study included only two assessment points, they were unable to test models of curvilinear relationships over time or to address whether the observed changes in patterns of symptoms persist or change over longer time periods. Moreover, both studies only included acute responses lasting over the first 3-months after trauma exposure. Thus, neither study can address issues relevant to longer-term effects of drinking on the long-term course of PTSD.

In contrast, two additional studies found that alcohol-related variables did not predict PTSD symptom severity during the year after injury in hospitalized traumatic injury survivors (e.g., Zatzick et al., 2002, 2006). Traumatic injury was defined as violent assaults and motor vehicle crashes that led to hospital admission. Both studies included four assessment points and assessed numerous pre- and peri-traumatic factors encompassing mental health, physical health, and injury characteristic domains. In these studies, neither pre-injury alcohol use nor peritraumatic alcohol intoxication was retained in the final predictive models of PTSD symptoms over time. The repeated assessments and one-year follow up represent important study design improvements relative to the limitations of Kaysen et al. (2006) and McFarlane et al. (2009). However, the ultimate implications of these findings with respect to the relationship between alcohol and PTSD remain unclear because of limitations in the measurement of alcohol-related variables (e.g., the lack of measurement of alcohol use disorder at the time of injury, of alcohol-related negative consequences at the time of injury or during follow up, and of alcohol use during follow up).

The purpose of the present study is to examine the impact of alcohol misuse on the course of PTSD symptoms in female crime victims both in the acute phase and over the first six months after exposure. For the present study we hypothesized that alcohol use disorder at the time of the trauma and peak drinking level (i.e., greatest amount of alcohol consumption in the 30 days prior to the trauma) would moderate the course of PTSD over time. Specifically, we hypothesized that each of these variables would be associated with higher initial PTSD symptoms and a more severe and chronic course of PTSD symptoms. In addition, we hypothesized that drinking-related consequences in the month prior to the trauma and since the trauma would be associated with higher initial PTSD symptoms and a more severe and chronic course.

METHODS

Setting and Procedures

Initial screenings were conducted using a 5 to 10 minute telephone interview to explain study procedures and screen for English literacy, assault severity, and time since assault. Eligible participants were scheduled for a more comprehensive in-person assessment. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the project was reviewed and approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. In-person assessments were conducted by psychology graduate students or postdoctoral fellows at the University of Washington Medical Center. The assessments began with a complete discussion of the study and written informed consent. Each assessment was administered in two parts. In the first part, interviewers conducted diagnostic interviews for PTSD, alcohol use, and variables related to trauma history. In the second part, self-report questionnaires were administered via computer with the interviewer nearby for assistance. The assessments lasted approximately two to four hours. Approximately one month prior to each follow up assessment, participants were contacted to schedule the interviews. Participants completed assessments at three time periods: within five weeks of the assault (Time 1), three months post-assault (Time 2), and six months post-assault (Time 3). Participants were paid for their participation; they received a financial incentive that increased at each assessment ($50 for Time 1, $75 for Time 2, $100 for Time 3).

As the focus of the study was on the natural course of recovery from trauma, no treatment was provided. However, participants were not excluded from participation if they were enrolled in treatment at any point in the study. In addition, given the study focus on natural recovery, we included only participants who could be assessed within the first five weeks after trauma exposure. Acute reactions to trauma exposure appear to be normative, and most individuals who suffer from trauma-related symptoms show a notable decrease in symptoms without clinical intervention over the first four to five weeks (Riggs et al., 1995; Rothbaum et al., 1992). Thus, the first assessments were conducted within five weeks to capture the acute period of initial trauma responses following trauma exposure.

Participants

Female assault victims in the Seattle metropolitan area were recruited through hospitals and victim service agencies. Flyers were posted or distributed around the greater Seattle metropolitan area (e.g., college campuses, hospital emergency rooms, domestic violence shelters, grocery stores). Advertisements were also placed in local community newspapers. Of the women enrolled in the study, 13% were informed of the study at hospitals or victim service agencies, 15% found out about the study through advertisements, 46% saw flyers, 11% were referred via word of mouth, and 15% did not indicate how they heard about the study. Inclusion criteria included: 1) the assault met DSM-IV criterion A for PTSD, and 2) the assault occurred within the past five weeks. Eleven individuals were excluded for the following reasons: 1) current delusions or psychosis (n = 4), 2) lack of English literacy (n = 1), 3) more than five weeks post-trauma at the initial phone screen (n = 3), 4) did not meet assault criteria (n = 2), and 5) intoxication during the in-person assessment (n = 1).

Assaults consisted of sexual (n = 24; completed vaginal, oral, or anal penetrative assault) or first-degree physical assaults (n = 40; experienced injury or felt perpetrator was trying to kill/injure her). The mean age was 35.6 years (SD = 9.0; range = 19-53). The majority of participants had received at least a high school education (n = 49, 77%) and 45% (n = 29) had attended at least some college. Only 16% (n = 10) had competed college or earned a higher degree. Fifty-two percent (n = 33) of participants were single, 19% (n = 12) were married/ cohabiting, and the remainder (n = 18) were separated, widowed, or divorced. Seventy percent (n = 45) earned less than $10,000 annually. Twenty-nine percent (n = 18) identified as African American, 44% (n = 28) Caucasian, 5% (n = 3) Asian/Pacific Islander, 14% (n = 9) Native American, and 8% (n = 5) other. Twelve percent (n = 8) of the participants identified as Hispanic/Latina. Of participants assessed at Time 1 (n = 64), 81% returned for Time 2 (n = 52), and 80% returned for Time 3 (n = 51). Seventy three percent of participants were seen at all three time points (n = 47).

Measures

A battery of interviews and self-report questionnaires were administered to participants, of which the following were relevant to the purposes of this study:

Demographics, including age, racial background, ethnicity, education, and income were assessed.

The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) is a clinician-administered diagnostic interview that measures PTSD and has been found to have excellent psychometric properties (Blake et al., 1995). For each symptom, a clinician rates two separate dimensions, frequency and intensity of symptoms, on a scale ranging from 0-4. In order for a symptom to be considered clinically significant, it must meet threshold criteria on both dimensions, i.e., at least a ‘“1” on frequency and a “2” on intensity. The scale yields both a PTSD diagnosis and a continuous measure of PTSD severity including intrusive, hyperarousal, and avoidance symptoms. The CAPS was used to assess current PTSD symptom severity at each time point.

The Depression and Substance Use Disorders modules of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV; First, Spitzer & Williams, 2001) are clinician-administered, structured interviews that were used to assess current and lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence diagnoses and current and lifetime major depressive disorder diagnoses at baseline, and current alcohol use disorder and major depressive disorder at follow-up.

Timeline Follow-back Interview (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) was used for assessment of alcohol consumption patterns for the 30 days prior to the assault. The TLFB has been found to have good psychometric properties (Sobell, Brown, Leo, & Sobell, 1996). Although the TLFB can be scored in multiple ways, for the present study we concentrated on peak number of drinks on one occasion over the past 30 days. Peak drinks were chosen as the primary outcome measure for consumption because of prior research suggesting that this variable is predictive of PTSD symptoms in an acute, trauma-exposed sample of women (Kaysen et al., 2007). Models were also examined using total number of drinking days and total number of drinks over past 30 days; these results were highly similar to those involving peak drinks and thus only that outcome is reported below.

The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC-2R; Project MATCH Research Group, 1997) was used as a measure of alcohol-related negative consequences. This 50-item scale measures a broad range of drinking consequences in the past 30 days on a 4-point Likert scale, such as, “I have had a hangover after drinking,” and, “I have lost interest in activities and hobbies because of my drinking.” The DrInC-2R has been shown to have good reliability, validity, and both research and clinical utility (Forcehimes, Tonigan, Miller, Kenna, & Baer, 2006). This measure was administered for the 30 days prior to the assault, as well as the 30 days prior to the 3- and 6-month assessments.

The Traumatic Life Event Questionnaire (TLEQ; Kubany et al., 2000) is a 23-item measure of 22 types of potentially traumatic events, including natural disasters, sexual assaults, and physical assault. The TLEQ also asks individuals to choose their most distressing event and to provide the age at which it first occurred. The TLEQ has demonstrated good content validity in assessing trauma across several different experiences (Kubany et al., 2000).

Family History of Alcohol Problems was assessed using a scale from the Brief Drinker Profile (BDP; Miller & Marlatt, 1984). Participants reported whether any biological maternal or paternal family member or sibling might have had a significant drinking problem - i.e., one that did or should have led to treatment. This measure has been shown to have good construct validity compared to other family history measures (Larimer, et al., 2001; Turner, et al., 2000).

Data Analyses

The primary goal of the current study was to model the change in PTSD symptoms directly after an assault and for approximately the following six months. Because women contacted the project and were scheduled for assessments at different times, data across assessments varied with respect to days since the assault (Time 1 assessment: M = 26.6, SD = 9.9; Time 2 assessment: M = 102.9, SD = 15.0; Time 3 assessment: M = 193.7, SD = 20.2). In addition, there were some missing data, leading to data imbalance in number as well as timing. Because of our interest in modeling change longitudinally and the aforementioned characteristics of the data, hierarchical linear models (HLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002, also called multilevel or mixed-effects models) were used for all analyses.

The basic HLM that we used took the following form (using current alcohol use disorder as an example):

where i indexes participants and t indexes time. Descriptive analyses revealed a curvilinear slope for PTSD across time that was well described by a log transformation for time. The model includes random intercepts and slopes at level 2 (i.e., r0i, r1i), which describe individual variability in initial severity of PTSD and change over time. The key terms for testing the hypotheses are β01 and β11, which describe the differences in PTSD symptoms just following the assault (i.e., intercept) and over the next six months (i.e., slope) for those who had an active alcohol use disorder during the 30 days prior to the trauma versus those participants who did not - a form of moderation analysis. Finally, the model assumes normally distributed and homoskedastic residuals, which was checked via residual plots. A second, similar model used peak drinking during the 30 days prior to the trauma from the TLFB as the level two covariate (instead of alcohol use disorder).

Drinking consequences were measured at each time point and treated somewhat differently in the analyses. Consequences were divided into two variables: a) severity of drinking consequences experienced during the 30 days prior to the assault (i.e., baseline drinking consequences), and b) changes in consequences from baseline to three months and from baseline to six months. This approach allowed us to examine the association of consequences that occurred during the 30 days prior to the assault with the course of PTSD, as well as whether changes in drinking consequences interacted with course of PTSD over time.

As a sensitivity analysis, we used propensity scores to examine whether participants with and without alcohol use disorder were notably different on background characteristics and whether those differences influenced the observed results. Propensity scores formalize the ideas behind including covariates in treatment studies (Gelman & Hill, 2007; Rosenbaum, 2002). The basic process was to form a logistic regression equation using alcohol use disorder as the outcome and background characteristics as covariates. The logistic regression can inform where there might be imbalance between the two groups, but more importantly, the estimated probabilities of alcohol use disorder status from this model serve as a single summary of the background imbalance. Thus, although the propensity score model might have a large number of covariates (e.g., 20 or more), any group imbalance gets summarized by the predicted probabilities, a single covariate, which can then be included in the primary analyses, here HLMs.

In this study, demographic variables (i.e., age, race, ethnicity, education, income), trauma variables (i.e., lifetime number of traumas, age at worst trauma, whether assault was sexual assault), and psychological variables (i.e., lifetime major depression, family history of alcohol problems) were included in the propensity score model. Predicted probabilities were estimated from the logistic regression and included as an additional covariate in the models including alcohol use disorder, peak drinks, and drinking consequences.

Finally, we examined whether effects were driven by a particular PTSD symptom cluster: intrusion, hyperarousal, or avoidance. These subscales were modeled simultaneously using a multivariate HLM that allowed the outcomes to be correlated with one another. Two models were tested: a) one that forced a single intercept and slope across outcomes, and b) a second model that fit outcome-specific (i.e., subscale-specific) intercepts and slopes. The model comparison between these two would identify whether any observed effects were common across the subscales or, alternatively, were being driven by a single subscale (or some combination). All analyses were done using R v2.11.1 (R Development Core Team, 2010) and made use of the nlme package for linear and nonlinear mixed-effects models (Pinheiro et a., 2010).

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

At Time 1 (within five weeks of the assault), 48% (n = 31) of the participants met criteria for PTSD only, 9% (n = 6) met criteria for current alcohol abuse or dependence only, 14% (n = 9) met criteria for both PTSD and current alcohol abuse or dependence, and 28% (n = 18) met criteria for neither PTSD nor alcohol abuse or dependence. Participants drank an average of 3.8 drinks (SD = 5.5) on a peak drinking occasion during the 30 days prior to the assault. Average drinking consequences scores were 35.8 pre-assault (SD = 50.3) and 18.2 (SD = 18.2) 6 months post-assault. Time 1 drinking consequences and alcohol use disorder diagnosis were significantly correlated, r = .38, p = .002. Average PTSD symptom severity post-assault was 62.0 (SD = 27.3) and at 6 months was 40.9 (SD = 28.8). Table 1 reports PTSD symptom severity and drinking outcomes by diagnostic group.

Table 1.

PTSD Symptom Severity, Trauma Exposure, and Drinking Outcomes by Diagnostic Category at Time One (n = 64).

| Diagnostic Type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PTSD only (n = 31) |

AUD only (n = 6) |

PTSD + AUD (n = 9) |

No Diagnosis (n = 18) |

|

|

|

||||

| Variable | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| CAPS Total Score | 79.1 (17.4) | 32.5 (23.6) | 73.2 (23.0) | 36.8 (15.1) |

| CAPS Intrusive Subscale | 22.0 (8.1) | 10.0 (10.6) | 17.4 (9.0) | 11.1 (5.7) |

| CAPS Hyperarousal Subscale | 26.5 (6.8) | 11.0 (9.2) | 24.3 (8.3) | 13.6 (8.1) |

| CAPS Avoidance Subscale | 30.6 (7.7) | 11.5 (10.3) | 31.4 (10.4) | 12.1 (7.5) |

| Number of Traumatic Events† | 7.5 (4.2) | 9.6 (5.2) | 7.1 (3.5) | 4.8 (3.2) |

| Peak Drinking | 3.2 (5.8) | 7.0 (2.8) | 9.5 (7.4) | 2.0 (2.4) |

| Total Drinking Days | 2.0 (3.2) | 12.0 (10.7) | 12.8 (11.0) | 4.1 (7.6) |

| Drinking Consequences | 72.8 (41.8) | 127.2 (22.5) | 126.3 (40.2) | 73.8 (49.1) |

|

| ||||

| n (%)* | n (%)* | n (%)* | n (%)* | |

|

|

||||

| Family Alcohol History | 20 (31.2) | 5 (7.8) | 8 (12.5) | 8 (12.5) |

| Major Depressive Disorder (Lifetime) |

29 (48.3) | 4 (6.7) | 8 (13.3) | 9 (15) |

Note. PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale.

Based on Traumatic Life Event Questionnaire.

Percentage based on total sample.

PTSD Over Time by Alcohol

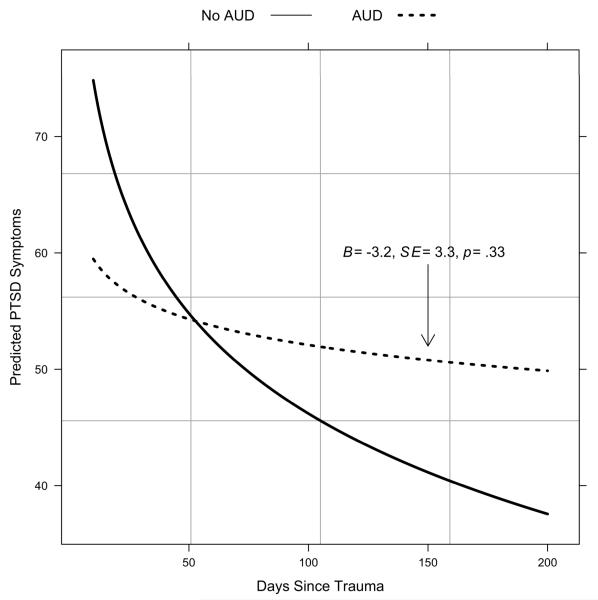

Table 2 reports coefficients, 95% confidence intervals for the (previously described) HLM analyses using alcohol use disorder, peak alcohol use, and consequences during the 30 days prior to assault as moderators. As discussed above, our primary focus was on whether the aforementioned variables had significant main effects and/or interacted significantly with time (log transformed). As shown in Table 2, there was a main effect of alcohol use disorder and a significant interaction between alcohol use disorder and time (log transformed) such that those individuals with a current alcohol use disorder diagnosis at the time of the assault scored, on average, 36 points lower on the PTSD outcome measure at the first assessment. In addition, the slope over time for the alcohol use disorder subgroup was far shallower than the non-alcohol use disorder subgroup, as seen by the positive interaction coefficient. Moreover, the simple slope for the alcohol use disorder subgroup was not significant (B = −3.2, 95% CI for B = −9.7, 3.3), indicating that there was not a significant decrease in PTSD symptoms over time. The simple slopes are plotted in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Fixed-effects and 95% Confidence Intervals for Three Hierarchical Linear Models Examining Alcohol Use Disorder, Peak Drinking, and Drinking Consequences as Moderators of PTSD Symptoms

| 95% Confidence Interval |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | B | lower limit | upper limit |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | |||

| Intercept | 103.46* | 87.98 | 118.93 |

| Current Alcohol Use Disorder | −36.59* | −68.67 | −4.50 |

| Time | −12.43* | −15.96 | −8.91 |

| Current Alcohol Use Disorder x Time | 9.23* | 1.87 | 16.58 |

| Peak Drinking | |||

| Intercept | 95.10* | 80.89 | 109.30 |

| Peak Drinking | −5.34 | −19.52 | 8.85 |

| Time | −10.37* | −13.63 | −7.12 |

| Peak Drinking x Time | 1.65 | −1.63 | 4.93 |

| Drinking Consequences | |||

| Intercept | 92.44* | 78.29 | 106.58 |

| Drinking Consequences (Time 1) | −44.34* | −82.54 | −6.14 |

| Drinking Consequences (Deviations) | 0.70 | −0.44 | 1.83 |

| Time | −9.80* | −13.12 | −6.47 |

| Drinking Consequences (Time 1) x Time | 12.59* | 2.81 | 22.36 |

| Drinking Consequences (Deviations) x Time | −0.16 | −0.41 | 0.08 |

Note.

p<.05. PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Drinking consequences was a time- varying covariate and modeled in two parts: Drinking consequences reported at Time 1, and the change (i.e., deviations) at Time 2 and Time 3 from the reported consequences at Time 1. Note that time was log transformed to linearize its relationship with the outcome and that peak drinking and drinking consequences were log transformed due to highly skewed distributions.

Figure 1.

Predicted Regression Lines From HLM of PTSD Symptoms on Current Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) and Time Since Assault

In contrast, in the HLM investigating peak drinking and PTSD symptoms, there was no main effect or interaction of peak drinking and time (log transformed). Thus, peak drinking over the 30 days prior to the assault was not a significant predictor either of initial PTSD symptoms or change in symptoms over time.

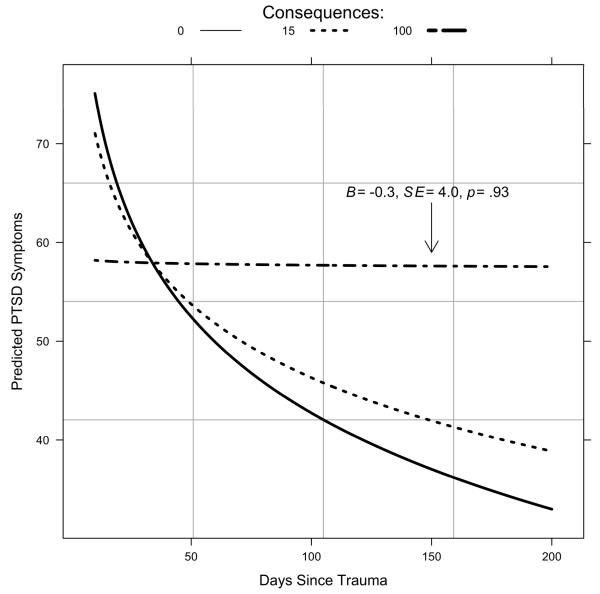

Similar to current alcohol use disorder, drinking consequences during the month prior to assault were significantly related to the level of PTSD symptoms experienced initially and the change over time. However, changes in drinking consequences over time did not significantly interact with changes in PTSD symptoms. The simple slopes for drinking consequences are plotted in Figure 2, using the 10th, 50th, and 90th quartiles of consequences during the month prior to assault. As seen in Figure 2, at higher levels of drinking consequences during the month prior to assault, the slope of PTSD symptoms over time is not significant. To better understand the interaction between prior month drinking consequences and change in PTSD symptoms, we examined the region of significance for the interaction, i.e., at what slope value is the simple slope no longer significant? (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). We found that the simple slope of PTSD on days following the assault was no longer significant at DrInC values higher than 52.

Figure 2.

Predicted Regression Lines From HLM of PTSD Symptoms on Drinking Consequences at Time 1 and Time Since Assault

We then retested our models for alcohol use disorder and negative drinking consequences after including the propensity score model to control for demographics, trauma variables, and psychological variables. In both cases, conclusions were identical whether or not the propensity scores were included, and there were no differences in magnitude or significance of predictors. Thus, the results of this analysis would suggest that the background characteristics included in the propensity score equation did not function as confounders (i.e., third variables associated with both PTSD symptoms and drinking variables).

Finally, multivariate HLMs were fit such that the three PTSD subscales (i.e., intrusions, hyperarousal, and avoidance) were modeled simultaneously over time. These analyses were used to examine whether a specific cluster (or clusters) of PTSD symptoms was driving the effects seen above. For both alcohol use disorder status and drinking consequences during the 30 days prior to assault, the multivariate HLMs were not significantly improved by allowing intercepts and slopes to vary across cluster outcomes based on deviance tests for model comparison (χ2 (6) = 2.1, p = .91 and χ2 (10) = 5.5, p = .85 for alcohol use disorder and drinking consequences, respectively). Thus, no individual cluster of PTSD symptoms appeared to account for the relationship between alcohol use disorder, drinking consequences, and PTSD severity or course.

DISCUSSION

Summary of Findings

The present study is part of a growing body of literature addressing the impact of alcohol use on PTSD over time in acute trauma samples (Acierno et al., 1999; Kaysen et al., 2006; Zatzick et al., 2002). This study expanded upon previous findings suggesting that women with prior alcohol use disorder are at increased risk for PTSD (Acierno et al., 1999; Cottler et al., 1992) by considering the impact of alcohol use and problems on both early PTSD symptoms and recovery over time. Contrary to our hypotheses, alcohol use disorder and pronounced alcohol-related consequences during the month prior to trauma exposure were associated with significantly lower reports of PTSD symptoms immediately post-trauma exposure. However, as hypothesized, both factors were associated with less PTSD symptom improvement over time. Due to the small sample size, results should be seen as exploratory. The results provide preliminary but convergent evidence that alcohol consequences at the time of trauma influence initial severity and chronicity of PTSD symptoms. Given that there is substantial overlap between alcohol use disorder status and severity of alcohol-related consequences, the results suggest that this is the case whether alcohol consequences are dichotomized, as would be done clinically and diagnostically, or when treated continuously.

Results did not support the other a priori hypothesis that pre-trauma alcohol consumption would similarly be associated with higher PTSD symptoms initially and poorer recovery over time. Instead, we found no significant relationship between peak use prior to the trauma and course of PTSD symptoms. Neither did we find any relationship with other commonly evaluated indices of alcohol use, namely days drinking or overall amount of alcohol consumed (see also McFarlane et al., 2009; Zatzick et al., 2002; 2006).

The present study adds to previous work in several ways. This is the first study to assess both alcohol use and problems within the initial, acute phase after sexual or physical assault in a community sample of women. The use of longitudinal data allowed for better understanding of the impact of alcohol use and problems on the process of natural recovery from trauma-related symptoms. Overall retention rates in this sample of recently traumatized women were good. In addition, the use of propensity scores to control for potential confounds helped to conserve statistical power by consolidating a number of different person factors that would otherwise have had to be in the models individually.

Limitations

There are also several important limitations to note. There are a number of other confounding variables that we did not include in our analyses. Many of the women in our sample had prior trauma histories, and they may have had previous courses of PTSD. While we did take into account number of previous traumas through the propensity score, we did not assess number of lifetime PTSD episodes, and future work would benefit from inclusion of this information. We did not examine treatment that participants may have received for PTSD or for substance misuse either before the trauma or during the six month follow-up phase. Nor did we include ongoing traumatization, which may also have played a role in the chronicity of PTSD symptoms (Hedtke, Ruggiero, Fitzgerald, Zinzow, Saunders, Resnick, & Kilpatrick, 2008). We did not examine drug use, including prescription narcotics or benzodiazepines. Use of these drugs is prevalent among PTSD samples and may affect natural recovery following traumatic stressors (Matar, Zohar, Kaplan, & Cohen, 2009; McCauley, Amstadter, Danielson, Ruggiero, Kilpatrick, & Resnick, 2009; Zatzick & Roy-Byrne, 2006). We also did not examine the possible mitigating role of social support, which can also affect PTSD course and be affected by substance misuse (Ullman, Starzynski, Long, Mason, & Long, 2008). Further examination of these important issues would be useful to the literature but is beyond the scope of the current paper.

The study had several methodological limitations as well. The study only followed women for six months following trauma exposure and thus cannot address the impact of alcohol on long-term recovery from trauma. The study relied solely on self-report measures of alcohol use and trauma exposure and might not accurately reflect alcohol use or trauma exposure of our participants. Although self-report has generally been found to match reports of alcohol use from collateral sources, it is possible that participants underreported these behaviors. To mitigate this, all efforts were made to ensure confidentiality of reporting.

The study also was limited by a relatively small sample size. Although our current sample should be sufficient for the primary HLM analyses, it is possible that with a larger sample size, there would have been greater power to detect effects. In particular, the sample size may have limited our ability to find an effect of alcohol consumption on PTSD. Thus, a lack of findings for the role of alcohol consumption on PTSD course should be interpreted with caution. Our small sample size also prohibited us from examining subgroup differences. For example, we were unable to examine alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence separately. It is likely that the women in our sample who reported the highest levels of alcohol-related consequences (see Figure 2) would meet criteria for alcohol dependence given that one must have experienced several such consequences to qualify for the diagnosis. In addition, the small sample size and makeup of the sample (only women, recent physical or sexual assault exposure, low income) may limit our ability to generalize to other samples. Given the overrepresentation of low income participants, it is unclear whether the composition of the sample may reflect a sampling bias. Women who were lower income may have been more able or willing to participate in the research study. These concerns are somewhat offset by the overall similarity of our results to those found in larger samples of recent injury victims (McFarlane et al., 2009; Zatzick et al., 2002, 2006).

Implications

In this study, marked alcohol-related consequences and positive alcohol use disorder status at the time of trauma exposure were related to initial presentation and course of PTSD in the immediate aftermath of an assault. Interestingly, the findings for alcohol use diverged from this pattern. Specifically, results regarding alcohol-related consequences and alcohol use disorder were consistent with the self-medication hypothesis, i.e., apparent suppression of initial PTSD symptoms and worse chronicity, presumably due to avoidance and interference with trauma processing. However, we did not find evidence of this pattern for alcohol use (see also McFarlane et al., 2009). Should these findings be replicated with larger samples, they raise the question: What aspect of alcohol-related consequences influences the course of recovery following trauma exposure?

Various types of consequences can be associated with more problematic alcohol use, including compromised work and social role functioning, legal involvement, health issues, and inter- and intrapersonal difficulties, such as broken or impaired relationships or strong feelings of guilt and shame regarding drinking (Project MATCH Research Group, 1997). Individuals with few practical, social, or personal resources in place prior to exposure to a trauma may well not be able to cope adequately with yet another setback, let alone a traumatic event. Future research evaluating whether there are particular types of alcohol consequences associated with poorer natural recovery would be beneficial both conceptually and clinically.

Identifying those most at risk for PTSD is important in appropriately targeting early interventions to those who need it, as well as developing effective prevention programs for those who are at risk following trauma exposure (Litz, Gray, Bryant, & Adler, 2006). Typically those individuals with lower PTSD symptoms in the immediate aftermath also have lower risk of PTSD three to six months following trauma exposure (Kilpatrick, Veronen, & Best, 1985; Girelli, Resick, Marhoefer-Dvorak, & Hutter, 1986; Rothbaum et al., 1992). Our findings suggest that lower PTSD symptom severity following trauma exposure among drinkers may not necessarily indicate reduced risk for PTSD over time. Given that early interventions may not be offered to those who initially present with lower PTSD symptoms, it is possible that these particular individuals may be missed using indicated prevention (Roberts, Kitchiner, Kenardy, & Bisson, 2009). Accordingly, these findings suggest a need for routinely assessing alcohol problems, not just alcohol consumption itself, both prior to and in the months following trauma exposure. In one study, a videotaped brief intervention for PTSD was found to improve later marijuana use but did not reduce alcohol use three to six months following trauma exposure (Resnick, Acierno, Amstadter, Self-Brown, & Kilpatrick, 2007). However, this study did not select for individuals endorsing problems with alcohol or higher negative consequences from drinking. Given our findings, providing a brief PTSD intervention for trauma exposed individuals who are also endorsing difficulties with drinking may facilitate natural recovery. Conversely, reducing the degree of problems associated with alcohol use could, in turn, encourage PTSD recovery (Zatzick et al., 2004). Research examining which presenting problem to address first in an acute trauma exposed sample, or whether to address both concurrently, would be invaluable in addressing the needs of trauma exposed populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the women who participated in this research study, as well as the community agencies that assisted with participant recruitment. We wish to thank Nicole Fossos, Hong Ngyuen, and Neharika Chawla for their assistance in data collection, and Dr. Mary Larimer for her consultation and guidance throughout the project. Data collection and manuscript preparation was supported by grants from the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (F32AA014728, PI: Debra Kaysen) and a grant from the Alcohol Beverage Medical Research Foundation (PI: Tracy Simpson and Debra Kaysen). The content here is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsors. Portions of these results were presented at the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Annual Meeting (November 2008) in Chicago, Illinois.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

REFERENCES

- Acierno R, Resnick H, Kilpatrick DG, Saunders B, Best CL. Risk factors for rape, physical assault, and posttraumatic stress disorder in women: Examination of differential multivariate relationships. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1999;13(6):541–563. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(99)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SE, Sonne SC, Killeen T, Dansky BS, Brady KT. Comparative profiles of women with PTSD and comorbid cocaine or alcohol dependence. American Journal of Drug & Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29(1):169–189. doi: 10.1081/ada-120018845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisby JA, Brewin CR, Leitz JR, Curran VH. Acute effects of alcohol on the development of intrusive memories. Psychopharmacology. 2009;204:655–666. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP. The Importance of the Peritraumatic Experience in Defining Traumatic Stress. Psychological Bulletin. 2010 Nov 22; doi: 10.1037/a0021353. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0021353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Back SE, Coffey SF. Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13(5):206–209. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, Schultz L. Psychiatric sequelae of posttraumatic stress disorder in women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(1):81–87. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130087016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AL, Testa M, Messman-Moore TL. Psychological consequences of sexual victimization resulting from force, incapacitation, or verbal coercion. Violence Against Women. 2009;15:898–919. doi: 10.1177/1077801209335491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Posttraumatic stress disorder and drug disorders: Testing causal pathways. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:913–917. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Stewart SH. Experimental studies exploring functional relations between posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder. In: Ouimette P, Brown PJ, editors. Trauma and substance abuse: Causes, consequences, and treatment of comorbid disorders. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2003. pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Compton WM, Mager D, Spitznagel EL, Janca A. Posttraumatic stress disorder among substance users from the general population. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149(5):664–670. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.5.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darves-Bornoz J, Lepine J, Choquet M, Berger C, Degiovanni A, Gaillard P. Predictive factors of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims. European Psychiatry. 1998;13(6):281–287. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(98)80045-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood AM, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Weathers FW, Eakin DE, Benson TA. Substance use behaviors as a mediator between posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health in trauma-exposed college students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:234–243. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Huppert JD, Cahill SP. Emotional processing theory: An update. In: Rothbaum BO, editor. Pathological anxiety: Emotional processing in etiology and treatment. The Guilford Press; New York: 2006. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Rothbaum BO. Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD. The Guilford Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Forcehimes AA, Tonigan JS, Miller WR, Kenna GA, Baer JS. Psychometrics of the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC) Addictive Behaviors. 2006;32:1699–1704. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74(3):223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG, Bissett RT, Pistorello J, Toarmino D, Polusny M,A, Dykstra TA, Batten SV, Bergan J, Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH, Bond FW, Forsyth JP, Karekla M, McCurry SM. Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record. 2004;54:553–578. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of the literature. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1184–1190. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Simpson T, Dillworth T, Larimer ME, Gutner C, Resick PA. Alcohol problems and posttraumatic stress disorder in female crime victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(3):399–403. doi: 10.1002/jts.20122. doi: 10.1002/jts. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Morris M, Rizvi S, Resick P. The role of perceived threat in female victims’ within-trauma responses. Violence Against Women. 2005;11(12):1515–1535. doi: 10.1177/1077801205280931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Scher C, Mastnak J, Resick P. Cognitive mediation of childhood maltreatment and adult depression. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36(3):235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80072-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Haynes SN, Leisen MB, Owens JA, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Burns K. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:210–224. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: A review of major perspectives and findings. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(2):149–171. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeies M, Pagura J, Sareen J, Bolton JM. The use of alcohol and drugs to self-medicate symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2010 doi: 10.1002/da.20677. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1002/da.20677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Grills-Taquechel A, Axsom D. Impaired and incapacitated rape victims: Assault characteristics and post-assault experiences. Violence and Victims. 2009;24:439–457. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS. To have but one true friend: Implications for practice of research on alcohol use disorders and social networks. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:113–121. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC, Browne D, Bryant RA, O’Donnell M, Silove D, Creamer M, Horsley K. A longitudinal analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of posttraumatic symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;118:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.017. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teeson M, Ross J, Peters L. Trauma, PTSD, and substance use disorders: Findings from the Australian National Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:651–658. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24(8):981–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette P, Read JP, Wade M, Tirone V. Modeling associations between posttraumatic stress symptoms and substance use. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.009. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, the R Development Core Team nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. [Software] R package version 3. 2010:1–97. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, Capone C, Sheets E, Young D, Chelminski I, Zimmerman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder with and without alcohol use disorders: Diagnostic and clinical correlates in a psychiatric sample. Psychiatry Research. 2009;170:278–281. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.015. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Brown PJ, Kahler CW. Substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders: Symptom interplay and effects on outcome. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1665–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DS, Rothbaum BO, Foa EB. A prospective examination of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in victims of nonsexual assault. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1995;10(2):201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DS, Rukstalis M, Volpicelli JR, Kalmanson D, Foa EB. Demographic and social adjustment characteristics of patients with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence: Potential pitfalls to PTSD treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1717–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.044. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Foa EB, Riggs DS, Murdock T, Walsh W. A prospective examination of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1992;5(3):455–475. [Google Scholar]

- Slone LB, Norris FH, Gutiérrez Rodriguez F, Gutiérrez Rodriguez J, Murphy AM, Perilla JL. Alcohol use and misuse in urban Mexican men and women: An epidemiologic perspective. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;85:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.006. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonne SC, Back SE, Zuniga CD, Randall CL, Brady KT. Gender differences in individuals with comorbid alcohol dependence and post-traumatic stress disorder. American Journal on Addictions. 2003;12(5):412–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spak L, Spak F, Allebeck P. Sexual abuse and alcoholism in a female population. Addiction. 1998;93(9):1365–1373. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93913657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R-Non-Patient Version (SCID-MDD) New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; New York, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH. Alcohol abuse in individuals exposed to trauma: A critical review. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120(1):83–112. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Conrod PJ, Pihl RO, Dongier M. Relations between posttraumatic stress symptom dimensions and substance dependence in a community-recruited sample of substance abusing women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13(2):78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Pihl RO, Conrod PJ, Dongier M. Functional associations among trauma, PTSD and substance-related disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23(6):797–812. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Mitchell TL, Wright KD, Loba P. The relations of PTSD symptoms to alcohol use and coping drinking in volunteers who responded to the Swissair Flight 111 airline disaster. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2004;18:51–68. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.07.006. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabatchnik BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. Allyn & Bacon; Needham Heights, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, D’Amico EJ, Wenzel SL, Golinelli D, Elliott MN, Williamson S. A prospective study of risk and protective factors for substance use among impoverished women living in temporary shelter settings in Los Angeles County. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Stazynski LL. Correlates of comorbid PTSD and drinking problems among sexual assault survivors. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.002. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Starzynski LL, Long SM, Mason GE, Long LM. Exploring the relationships of women’s sexual assault disclosure, social reactions, and problem drinking. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1235–1257. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli J, Balaraman G, Hahn J, Wallace H, Bux D. The role of uncontrollable trauma in the development of PTSD and alcohol addiction. Alcohol Research & Health. 1999;23(4):256–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatzick DF, Grossman DC, Russo JE, Pynoos R, Berliner L, et al. Predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms longitudinally in a representative sample of hospitalized injured adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;24(10):1188–1195. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000231975.21096.45. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000231975.21096.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatzick DF, Kang SM, Muller HG, Russo JE, Rivara FP, Katon W, Jurkovich GJ, Roy-Byrne P. Predicting posttraumatic distress in hospitalized trauma survivors with acute injuries. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):941–946. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Resnick HS, Amstadter AB, McCauley JL, Ruggiero KJ, Kilpatrick DG. Drug- or alcohol- facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape in relationship to mental health among a national sample of women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:2217–2236. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354887. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]