Abstract

Objective

This study examined relationships among family history of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems and substance use severity, interpersonal relationships, and service use in individuals with dual diagnosis.

Methods

Data were collected with the family history section of the Addiction Severity Index administered as part of three studies of individuals with dual disorders (N=413). Participants were categorized into family history risk groups for each problem domain based on the number of first and second degree relatives with alcohol, drug, or psychiatric problems.

Results

Rates of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems were high across family member categories and highest overall for siblings. Over two-thirds of the sample was categorized in the high-risk group in the alcohol problem domain, almost half of the sample was categorized as high-risk in the drug problem domain, and over a third of the sample was categorized as high-risk in the psychiatric problem domain. Across problem domains, individuals in the high-risk group reported more relationship problems with parents and siblings and higher rates of lifetime emotional, physical, and sexual abuse than did those in the low or moderate-risk groups.

Conclusions

Family history of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems is associated with greater rates of poor family relationships and history of abuse. Assessment of these different forms of family history in multiple family members can aid treatment providers in identifying individuals with dual disorders who may benefit from trauma-informed care as part of their overall mental health and substance abuse treatment services.

Keywords: dual diagnosis, family history, serious mental illness

Family history of substance abuse is an important correlate of problem severity in primary substance abusers (Kendler et al., 2008; Coviello et al., 2004; Pickens et al., 2001; Merikangas et al., 1998; Bierut et al., 1998; Boyd et al., 1999; Rutherford, Metzger & Alterman, 1994). Positive family history is associated with increased severity of substance use disorders as well as a range of family, social, and psychological problems (Boyd et al., 1999; Coviello et al., 2004; Pickens et al., 2001; Rutherford et al., 1994). Boyd and colleagues (1999) not only found a positive relationship between parental drug or alcohol problems and problem substance use in probands, but that this relationship was also strengthened when probands had two affected parents. Thus, severity of substance use problems may be affected by the number of relatives with problem use.

Less is known about the impact of family history of substance abuse for individuals with serious mental illness and substance use disorders. Research confirms high prevalence rates of substance use disorders and negative consequences in individuals with serious mental illness (Dixon, 1999; Lehman et al., 1994; Marshall, 1998; Reiger et al., 1990), but there has been little research on how family history impacts use and functioning among those with dual diagnosis. What has been done suggests that individuals with dual diagnosis have high rates of family history of problematic substance use, and that family history may impact use severity and consequences (Comptois et al., 2005; Davis et al., 2008; Morean et al., 2009; Rounsaville et al., 1991). Cantor-Graae, Nordstrom, and McNeil (2001) found that positive family history of substance abuse was correlated with participants’ substance abuse in a sample of 87 individuals with schizophrenia. In a sample of 89 individuals with serious mental illness, Comptois and colleagues (2005) found that positive family history was related to greater severity of substance-related consequences in the respondent. Smith and colleagues (2008) compared individuals with schizophrenia and their siblings without psychosis (n=59 probands, 53 siblings) to community controls and their siblings (n=80 controls, 75 siblings) on rates of substance use disorders. Those with schizophrenia and their siblings reported higher rates of alcohol and cannabis use disorders than did the comparison subjects and their siblings. In a large-scale study of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia, alcohol use disorders in mothers and fathers were independently associated with increased risk of disorder in probands (Jones et al., 2011).

Important questions remain about the impact of family history on those with dual diagnosis. First, while research has found that rates of family history of substance abuse are high, few studies have separated out family history of alcohol abuse from drug abuse to determine if there are differences. Another domain - family history of psychiatric problems – could also be especially relevant to individuals with dual diagnosis. Second, family history has been defined in a number of ways and has generally examined first-degree relatives (i.e., parents, siblings) without including secondary family members. Factors such as the number of relatives (single = parents only; multigenerational = parents + grandparents) and the proximity of the relative to the proband (high proximity = parents, siblings; low proximity = aunts, uncles, grandparents) may impact rates and have not been fully explored. Third, the impact of family history on important variables such as interpersonal relationships, abuse history, and service use has not been fully examined. Exploration of these issues would provide a more detailed picture of how family history relates to problems and functioning in individuals with dual diagnosis.

We examined rates of family history of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems and their impact on substance use severity, interpersonal relationships, and service use in individuals with dual diagnosis. We utilized self-report data on family history collected in three separate studies, and classified individuals into risk categories based on number and proximity of relatives. Our goals were to describe rates of these types of family histories, and to examine how having a positive family history in these different domains may impact substance use severity, interpersonal relationships, and service use. We expected high rates of family history of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems, and that problems would be highest among those with parental history. We also expected that higher risk individuals in all problem domains would show greater severity of substance use, more problematic relationships, and greater service use than those with lower risk.

METHODS

Participants

Data were collected across three studies: (1) a randomized trial of a behavioral intervention for substance abuse in individuals with serious mental illness who were seeking treatment for dependence (in the last 6 months) on cocaine, heroin, or marijuana (n=175; Bellack et al., 2006), (2) a survey of substance use and motivation to change in individuals with serious mental illness in the community who met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder or a non-psychotic affective disorder and for either current cocaine dependence or cocaine dependence in remission (n=240; Bennett et al., 2009), and (3) a pilot study of a behavioral intervention for individuals with serious mental illness and recent alcohol dependence (n=41). Inclusion criteria across studies were diagnosis of serious mental illness1; diagnosis of alcohol, cocaine, heroin, or marijuana dependence (within the last 6 months); age 18-65; and willingness to provide consent. Exclusion criteria were: documented history of neurological disorder or head trauma with loss of consciousness, mental retardation indicated by chart review, and inability to participate due to intoxication or escalation of psychiatric symptoms at assessment resulting in disruptive/aggressive behavior.

The sample (n=413) was predominantly male (64.9%), African American (73.4%), and unmarried (92.9%), with a mean age of 43.17 (SD=7.35) years and a mean of 11.82 (SD=2.23) years of education. Diagnostically, 64% had a current affective disorder, 33.1% had a current diagnosis of schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, and 3% had other diagnoses. Overall, 83.5% had a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol dependence and 97.4% had a lifetime diagnosis of drug dependence; 30.1 % met criteria for current alcohol dependence, and 62.9% for current drug dependence. Participants reported a mean of 4.59 (SD=6.46) episodes of alcohol abuse treatment and a mean of 6.04 (SD=5.81) episodes of drug abuse treatment.

Measures

Substance use and family history

The Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan, Alterman, et al., 1992; McLellan et al., 1992) was used to assess substance use and family history of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems. The ASI is a semi-structured interview that assesses lifetime and recent functioning in seven areas: medical, employment/economic, drug use, alcohol use, legal, family/social and psychiatric. The drug, alcohol, family history, family/social, and legal sections of the ASI were administered in all three parent studies; these sections have been the most reliable in serious mental illness (Carey, Cocco, & Correia, 1997; Hodgins and el-Guebaly, 1992; Zanis, McLellan, & Corse, 1997). Variables from the ASI included here were: (1) substance use severity (number of years of: drinking to intoxication, heroin use, cocaine use, marijuana use, any drug use; and number of times ever treated for: alcohol problems, drug problems), (2) relationship problems with family members (serious problems getting along with parents and siblings) and lifetime experience of abuse (emotional, physical, and sexual abuse), (3) history of legal problems (lifetime number of arrests and convictions), and (4) family history of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems. Participants completed an expanded family history section of the ASI (McLellan, Alterman et al., 1992; McLellan et al., 1992) asking respondents to report on the presence or absence of problem drug use, problem drinking, or psychiatric problems in maternal and paternal grandparents, mother and father, maternal and paternal aunts, maternal and paternal uncles, and siblings (including information on two brothers and two sisters). Specifically, respondents were asked if these relatives had “what could be called a significant alcohol, drug use, or psychiatric problem that did or should have led to treatment.” Participants could respond “I don’t know”, and adoptive and foster families were not included. Responses were then categorized by family member type - any grandparent, any parent, any aunt, any uncle, any sibling - and as long as at least one family member of that type was reported on, data were included. Rates of missing information (i.e., no relative reported on in the category) were: (1) Any grandparent: alcohol = 23 (5.3%), drug = 23 (5.6%), psychiatric = 22 (5.3%); (2) Any parent: alcohol = 14 (3.4%), drug = 16 (3.9%), psychiatric = 14 (3.4%); (3) Any aunt: alcohol = 19 (4.6%), drug = 20 (4.8%), psychiatric = 21(5.1%); (4) Any uncle: alcohol = 19 (4.6%), drug = 20 (4.8%), psychiatric = 21 (5.1%); (5) Any sibling: alcohol = 11 (2.7%), drug = 11 (2.7%), psychiatric = 12 (2.9%).

Service use and recent functioning

The Substance Use Event Survey for Severe Mental Illness (Bennett, Bellack, & Gearon, 2006) is a brief measure of recent (last 90 days) service use and functioning in several domains: medical, employment and support, alcohol and drug use, family and relationships, legal, psychological and emotional, victimization, changes in drug use, and reasons for seeking treatment. Psychometric properties and validity are good (see Bennett et al., 2006). Variables included here (all for last 90 days) were: inpatient drug or alcohol treatment, speaking with a professional about alcohol or drug problems, outpatient drug or alcohol treatment, psychiatric hospitalization, outpatient treatment for a psychiatric problem, and talking to a professional about family problems. Information on victimization, including violent crime, physical attack, rape, sexual assault, or other life threatening or serious injury, was also collected, as was the presence or absence of serious problems with a family member.

Procedures

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland School of Medicine approved all study procedures for the current study and the parent studies. Participants in the three parent studies were recruited from outpatient community clinics and a Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Baltimore, Maryland. Potential participants were identified either through regular screening of medical records of new intakes or via clinician referral. Medical records were then reviewed to determine preliminary eligibility, including diagnosis of serious mental illness. All potential participants completed a standardized informed consent process with trained recruiters and were advised that a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality would protect the information provided. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the informed consent document included the name of the Institutional Review Board that approved and monitored the study.

Participants first completed the diagnostic interview and generally completed the remaining assessments within a week. Trained masters or doctoral level interviewers administered all assessments. Interviewers were supervised biweekly by a doctorate level researcher. Where participants were enrolled in more than one of the parent studies, the most recent assessment was used; duplicate data were excluded.

Analyses

Family history variables were combined using a logic-based strategy to yield categories for alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problem domains: any grandparent, any parent, any aunt, any uncle, and any sibling. For each problem domain, three risk groups were created, based on a categorization strategy described by Coviello et al. (2004): (1) high-risk: two or more 1st degree relatives or one 1st degree plus two or more 2nd degree with a history of alcohol, drug, or psychiatric problems; (2) medium-risk: one 1st degree relative plus at least one 2nd degree relative or no 1st degree relative and at least two or more 2nd degree relatives with a history of alcohol, drug, or psychiatric problems; and (3) low-risk: one 2nd degree relative or no relative with a history of alcohol, drug, or psychiatric problems. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and chi-square tests were used to compare family history risk groups in each problem domain on variables tapping demographics, substance use severity, interpersonal relationships, legal and victimization variables, and recent substance abuse and mental health treatment use. For analyses using MANOVA, post-hoc univariate comparisons were examined only when the overall MANOVA was significant to protect against Type-I error. To address the number of individual ANOVAs and chi-square tests performed, a Bonferroni correction was applied for (1) variables tapping interpersonal relationships, legal and victimization variables (.05/30 tests = p values ≤ .0017 considered significant, p values ranging from .05 - .0016 considered suggestive), and (2) variables tapping recent substance abuse and mental health treatment use (.05/24 tests = p values ≤ .0021 considered significant, p values ranging from .05 - .0020 considered suggestive).

RESULTS

Rates of Alcohol, Drug, and Psychiatric Problems by Family Member Category

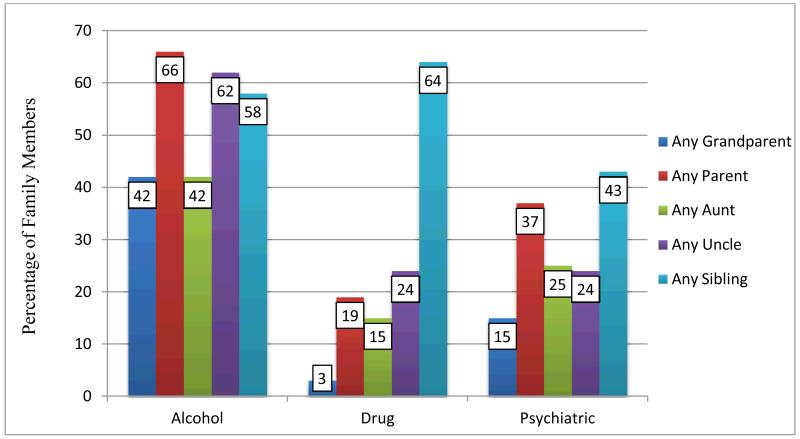

Rates of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems by family member category are presented in Figure 1. Rates of alcohol problems among family members were generally highest, followed by rates of psychiatric problems and rates of drug problems. The one exception was for problems among siblings, which ranged from 43% for psychiatric problems to 64% for drug problems. Rates of drug and psychiatric problems increased from older (i.e., grandparents) to more recent (i.e., siblings) generations.

Figure 1.

Percentage Rates of Self-Reported Alcohol, Drug, and Psychiatric Problems by Family Member Category (N=413)

Family History Risk Groups

Family history risk groups by problem domain are listed in Table 1. In the alcohol problem domain, over two thirds of the sample was categorized as high-risk. While the sample was more evenly distributed across risk groups in the drug problem domain, almost half of the sample was categorized as high-risk. In the psychiatric problem domain, over a third of the sample was categorized as high-risk, although the largest portion of the sample (44%) was in the low-risk group.

Table 1.

Family History Risk Groupsa for the Total Sample (N=413)

| High Risk (HR) n (%) |

Medium

Risk (MR) n (%) |

Low Risk (LR) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Family History, Alcohol Problems | 277 (67.01%) | 69 (16.71%) | 67 (16.22%) |

| Family History, Drug Problems | 192 (46.49%) | 89 (21.55%) | 132 (31.96%) |

| Family History,

Psychiatric Problems |

144 (34.87%) | 87 (21.01%) | 182 (44.01%) |

| Average % | 54.38% | 24.92% | 28.86% |

High risk = two or more 1st degree relatives or one 1st degree plus two or more 2nd degree with alcohol, drug, or psychiatric problem history; Medium risk = one 1st degree relative plus at least one 2nd degree relative or no 1st degree relative and at least two or more 2nd degree relatives with alcohol, drug, or psychiatric problem history; Low risk = only one 2nd degree relative or no relative with a history of alcohol, drug or psychiatric problems.

Comparison of Family History Risk Groups

For each problem domain, risk groups were compared on demographic variables (gender, age, marital status, current living situation, and level of education). In the alcohol and psychiatric problem domains, risk groups did not differ on any demographic variables. For the drug problem domain, those in the medium risk group were more likely to be female [x2 (2, 413) = 7.01, p = 0.03] and those in the low risk group were older [F(2,410) = 7.56, p = 0.001] and had more years of education [F(2, 402) = 3.05, p = 0.05] than those in the other risk groups.

MANOVAs were used to compare risk groups in each problem domain on substance use history variables (number of years of: drinking to intoxication, heroin use, cocaine use, marijuana use, any drug use; and lifetime number of times treated for alcohol problems or drug problems). None of the MANOVAs were significant; alcohol problem domain: F(12/722)=1.26, p=0.24; drug problem domain: F(12/722) = 0.63, p = 0.82; psychiatric problem domain: F(12/722) = 0.67, p = 0.79).

A series of ANOVAs and chi-square tests were used to compare risk groups in each problem domain on variables tapping family relationships, lifetime experience of abuse, recent victimization, and lifetime legal problems (Table 2). In each problem domain, the high-risk group generally showed more relationship problems and higher rates of most types of abuse than the other risk groups. For some types of abuse, rates in the medium-risk group were either similar to those in the high-risk group or fell in between rates of the high- and low-risk groups. Consistently, the low-risk group reported fewer relationships problems and lower rates of all types of abuse. In the alcohol problem domain, the high and medium risk groups reported more recent family problems than the low risk group. There were no differences among the risk groups on lifetime legal problems.

Table 2.

Comparison of Risk Groups on Relationship, Abuse/Victimization, and Legal Variables

| Variable | High Risk (HR) |

Medium Risk (MR) |

Low Risk (LR) |

Test/Value | df | P b | Post hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Problem Domain | |||||||

| Problems with mother (lifetime) | 164 (59.60%) | 31 (45.60%) | 30 (47.60%) | x2=6.19 | 2 | 0.045 | HR,MR>LR |

| Problems with father (lifetime) | 136 (53.10%) | 31(47.70%) | 19 (33.30%) | x2=7.38 | 2 | 0.025 | HR > LR |

| Problems with siblings (lifetime) | 173 (63.60%) | 28 (42.40%) | 22 (38.60%) | x2=18.33 | 2 | 0.0001 | HR > MR, LR |

| Emotional abuse (lifetime) | 232 (83.80%) | 48 (69.60%) | 31 (49/20%) | x2=35.53 | 2 | <0.0001 | HR > MR > LR |

| Physical abuse (lifetime) | 149 (54.20%) | 34 (49.30%) | 22 (34.90%) | x2=7.65 | 2 | 0.022 | HR > LR |

| Sexual abuse (lifetime) | 90 (32.70%) | 20 (29.00%) | 16 (25.40%) | x2=1.44 | 2 | 0.487 | |

| Problems with family (recentc) | 114 (41.2%) | 29 (43.3%) | 11 (16.4%) | x2=15.25 | 2 | <0.0001 | HR,MR>LR |

| Victimization (recentc) | 77 (27.8%) | 18 (26.5%) | 18 (26.9%) | x2=0.06 | 2 | 0.970 | |

| Number of arrests (lifetime) | 6.17 ± 11.79 | 5.65 ± 9.28 | 3.77 ± 7.41 | F=1.29 | 2/407 | 0.227 | |

| Number of

convictions (lifetime) |

3.65 ± 10.81 | 3.30 ± 7.07 | 2.24 ± 6.58 | F=0.54 | 2/404 | 0.581 | |

|

| |||||||

| Drug Problem Domain | |||||||

| Problems with mother (lifetime) | 110 (57.60%) | 51 (58.60%) | 64 (50.00%) | x2=2.25 | 2 | 0.325 | |

| Problems with father (lifetime) | 90 (51.10%) | 46 (55.40%) | 50 (42.0%) | x2=4.01 | 2 | 0.135 | |

| Problems with siblings (lifetime) | 130 (68.1%) | 45 (52.30%) | 48 (40.7%) | x2=23.01 | 2 | <.0001 | HR > MR, LR |

| Emotional abuse (lifetime) | 156 (81.30%) | 73 (82.0%) | 82 (64.1%) | x2=14.69 | 2 | 0.001 | HR, MR > LR |

| Physical abuse (lifetime) | 106 (55.5.0%) | 50 (56.20%) | 49 (38.60%) | x2=10.27 | 2 | 0.006 | HR, MR > LR |

| Sexual abuse (lifetime) | 77 (40.50%) | 23 (25.80%) | 26 (20.3%) | x2=16.01 | 2 | 0.0006 | HR > MR, LR |

| Problems with family (recentc) | 78 (40.8%) | 36 (40.4%) | 40 (30.5%) | x2=3.95 | 2 | 0.139 | |

| Victimization (recentc) | 55 (28.6%) | 21 (23.6%) | 37 (28.2%) | x2=0.84 | 2 | 0.656 | |

| Number of arrests (lifetime) | 6.98 ± 13.47 | 4.16 ± 4.99 | 4.88 ± 9.08 | F =2.64 | 2/407 | 0.073 | |

| Number of

convictions (lifetime) |

4.18 ± 12.73 | 2.19 ± 3.63 | 2.98 ± 6.90 | F=1.41 | 2/404 | 0.244 | |

|

| |||||||

| Psychiatric Problem Domain | |||||||

| Problems with mother (lifetime) | 94 (65.7%) | 43 (50.0%) | 88 (49.7%) | x2=9.51 | 2 | 0.009 | HR > LR |

| Problems with father (lifetime) | 81 (61.4%) | 39 (50.0%) | 66 (39.3%) | x2=14.44 | 2 | 0.001 | HR > LR |

| Problems with siblings (lifetime) | 104 (73.20%) | 45 (53.6%) | 74 (43.8%) | x2=27.59 | 2 | <0.0001 | HR > MR, LR |

| Emotional abuse (lifetime) | 127 (88.2%) | 65 (74.7%) | 119 (66.9%) | x2=20.00 | 2 | <0.0001 | HR > LR |

| Physical abuse (lifetime) | 97 (68.3%) | 41 (47.1%) | 67 (37.6%) | x2=30.19 | 2 | <0.0001 | HR > MR, LR |

| Sexual abuse (lifetime) | 61 (43.0%) | 24 (27.6%) | 41 (23.0%) | x2=15.26 | 2 | <0.0005 | HR > MR, LR |

| Problems with family (recentc) | 65 (45.1%) | 28 (32.6%) | 61 (33.7%) | x2=5.60 | 2 | 0.061 | |

| Victimization (recentc) | 50 (34.7%) | 20 (23.3%) | 43 (23.6%) | x2=5.92 | 2 | 0.052 | HR>MR,LR |

| Number of arrests (lifetime) | 5.88 ± 14.09 | 6.43 ± 9.25 | 5.23 ± 8.26 | F=0.38 | 2/407 | 0.683 | |

| Number of

convictions (lifetime) |

3.45 ± 12.97 | 3.25 ± 6.85 | 3.37 ± 7.68 | F=0.01 | 2/404 | 0.989 | |

High risk = two or more 1st degree relatives or one 1st degree plus two or more 2nd degree with alcohol, drug, or psychiatric problem history; Medium risk = one 1st degree relative plus at least one 2nd degree relative or no 1st degree relative and at least two or more 2nd degree relatives with alcohol, drug, or psychiatric problem history; Low risk = only one 2nd degree relative or no relative with a history of alcohol, drug or psychiatric problems.

p values ≤ .0017 considered significant, p values ranging from .05 - .0016 considered suggestive

Recent = Last 90 days

ANOVAs and chi-square tests were used to compare the risk groups in each problem domain on recent use of substance abuse treatment services, psychiatric treatment services, and talking to a professional about family problems (Table 3). In the alcohol problem domain, the high- and medium-risk groups were more likely to have talked to a professional about family problems than the low risk group. In addition, the high-risk group reported somewhat higher rates of talking to a mental health professional about alcohol use and somewhat higher rates of outpatient treatment for alcohol abuse than the low-risk group. There were no significant differences between the risk groups in the drug or psychiatric problem domains.

Table 3.

Comparison of Risk Groups on Recenta Use of Substance Abuse and Psychiatric Treatment Services

| Variable | High Risk (HR) |

Medium Risk (MR) |

Low Risk (LR) |

Test/Value | df | P b | Post hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Problem Domain | |||||||

| Talked with professional, alcohol use | 148 (53.4%) | 35 (51.5%) | 21 (31.8%) | x2=10.07 | 2 | 0.007 | HR > LR |

| Outpatient treatment for alcohol abuse | 186 (67.1%) | 42 (61.8%) | 33 (50.0%) | x2=6.87 | 2 | 0.032 | HR > LR |

| Talked with professional, drug use | 237 (85.9%) | 52 (76.5%) | 56 (83.6%) | x2=3.58 | 2 | 0.167 | |

| Outpatient treatment for drug abuse | 235 (85.1%) | 53 (77.9%) | 53 (80.3%) | x2=2.48 | 2 | 0.289 | |

| Inpatient psychiatric treatment | 86 (31%) | 23 (33.8%) | 17 (25.4%) | x2 =1.22 | 2 | 0.543 | |

| Use psychiatric medication | 266 (96.0%) | 67 (98.5%) | 62 (92.5%) | Fisher | - | 0.209 | |

| Outpatient psychiatric treatment | 183 (66.3%) | 40 (58.8%) | 37 (55.2%) | x2=3.54 | 2 | 0.170 | |

| Talked with professional, family problems | 114 (41.2%) | 29 (43.3%) | 11 (16.4%) | x2=15.25 | 2 | <0.0001 | HR,MR>LR |

|

| |||||||

| Drug Problem Domain | |||||||

| Talked with professional, alcohol use | 99 (51.6%) | 44 (50.0%) | 61 (46.6%) | x2=0.78 | 2 | 0.676 | |

| Outpatient treatment for alcohol abuse | 165 (86.4%) | 67 (75.3%) | 109 (83.8%) | x2=5.41 | 2 | 0.067 | |

| Talked with professional, drug use | 163 (85.3%) | 72 (80.9%) | 110 (84.0%) | x2=0.89 | 2 | 0.641 | |

| Outpatient treatment for drug abuse | 165 (86.4%) | 67 (75.3%) | 109 (83.8%) | x2=5.41 | 2 | 0.067 | |

| Inpatient psychiatric treatment | 57 (29.7%) | 29 (32.6%) | 40 (30.5%) | x2=0.24 | 2 | 0.887 | |

| Use psychiatric medication | 186 (96.9%) | 83 (93.3%) | 126 (96.2%) | Fisher | - | 0.342 | |

| Outpatient psychiatric treatment | 124 (64.9%) | 51 (57.3%) | 85 (64.9%) | x2=1.73 | 2 | 0.420 | |

| Talked with professional, family problems | 115 (61.2%) | 58 (65.2%) | 68 (53.5%) | x2=3.27 | 2 | 0.195 | |

|

| |||||||

| Psychiatric Problem Domain | |||||||

| Talked with professional, alcohol use | 80 (55.6%) | 43 (50.6%) | 81 (44.5%) | x2=3.97 | 2 | 0.138 | |

| Outpatient treatment for alcohol abuse | 92 (63.9%) | 62 (72.9%) | 107 (58.8%) | x2=5.02 | 2 | 0.081 | |

| Talked with professional, drug use | 124 (86.7%) | 71 (82.6%) | 150 (82.4%) | x2=1.25 | 2 | 0.535 | |

| Outpatient treatment for drug abuse | 118 (81.9%) | 72 (83.7%) | 151 (83.9%) | x2=0.24 | 2 | 0.887 | |

| Inpatient psychiatric treatment | 46 (31.9%) | 29 (33.7%) | 51 (28.0%) | x2=1.09 | 2 | 0.581 | |

| Use psychiatric medication | 140 (97.2%) | 82 (95.3%) | 173 (95.1%) | Fisher | - | 0.592 | |

| Outpatient psychiatric treatment | 92 (64.3%) | 56 (65.1%) | 112 (61.5%) | x2=0.43 | 2 | 0.806 | |

| Talked with professional,

family problems |

95 (66.9%) | 51 (60.0%) | 95 (53.7%) | x2=5.74 | 2 | 0.057 | |

High risk = two or more 1st degree relatives or one 1st degree plus two or more 2nd degree with alcohol, drug, or psychiatric problem history; Medium risk = one 1st degree relative plus at least one 2nd degree relative or no 1st degree relative and at least two or more 2nd degree relatives with alcohol, drug, or psychiatric problem history; Low risk = only one 2nd degree relative or no relative with a history of alcohol, drug or psychiatric problems.

p values ≤ .0021 considered significant, p values ranging from .05 - .0020 considered suggestive

Recent = Last 90 days

DISCUSSION

This study examined self-reported rates of family history of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems in individuals with dual diagnosis. In line with other research, alcohol problems were the most frequently reported problem among family members and were uniformly high, ranging from 42% among grandparents to 66% among parents (Boyd et al., 1999; Powell et al., 1982; Rounsaville et al., 1991). In the drug and psychiatric problem domains, rates of family history increased by generation, with younger family members (i.e., siblings) showing the highest rates of these problems. This pattern was particularly pronounced for drug problems – the rate of reported drug problems among siblings was over 60% while that of grandparents and parents was 3% and 19%, respectively. When we categorized participants into risk groups based on reported family history of alcohol, drug or psychiatric problems, over half of the total sample was classified as high-risk. The highest rate of high-risk categorization was for alcohol problems at 67%. While these rates are higher than what has been found in primary substance abusers (Rounsaville et al., 1991), they are consistent with findings from samples of individuals with serious mental illness (Cantor-Graae et al., 2001; Comptois et al., 2005). Because our rates include grandparents and siblings, they highlight how risk is evident within families and across generations. The increasing rate of family history problems from grandparents to siblings may be indicative of a generational accumulation of genetic and psychosocial influences that may increase risk for developing substance use and psychiatric disorders (Bierut et al., 1998; Kendler, Davis & Kessler, 1997). Assessing family history risk separately for alcohol and drug domains showed how patterns differ by domain: higher rates of family history of problems overall in the alcohol problem domain, and increasing rates of problems from older to younger generations in the drug problem domain. Family history of psychiatric problems was reported most often among parents and siblings.

Risk groups in each problem domain did not differ on alcohol or drug use severity. This was somewhat surprising as it was expected that more problems among family members would be related to higher substance use severity (Bierut et al., 1997, Kendler et al., 1997; Milne et al., 2009). There are several possible explanations for this finding. The sample had a long history of substance use and problems, and individuals were selected for participation in the three parent studies due to having substance dependence in the last one to six months. Given this level of disorder, there may not have been enough variability in substance use in the sample to find any impact of family history risk status. In addition, our data for the alcohol problems domain suggested that the high-risk group may have been more likely to have recently talked with a professional about alcohol use. While this finding was only suggestive, it illustrates a possible connection between family problems and treatment seeking: those in the highest risk group might be more likely to seek assistance for drinking problems and thus keep severity of problems lower than would be expected without treatment. In addition, it is possible that our measures of substance use severity – number of years of drinking or drug use and number of times treated for alcohol or drug problems - were not sensitive enough to detect differences among the risk groups. Perhaps including measures of quantity of recent drinking or drug use, time of heaviest use, or lifetime consequences experienced as a result of use would have helped us identify more subtle but still important differences in severity among the groups.

Most differences among risk groups in all problem domains were found in relationships with family members and the experience of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. The high-risk groups in each problem domain reported more problems with parents and siblings and were more likely to report histories of physical, sexual, and/or emotional abuse than the other risk groups; most of these differences were statistically significant and even those that were suggestive were still illustrative. For example, over 50% of those in the high-risk group in the alcohol problem domain reported past physical abuse in comparison to 35% of those in the low-risk group – a difference that did not meet the standard for statistical significance in this study but is still clinically meaningful. This pattern was especially pronounced in the psychiatric problem domain, where the high-risk group reported significantly higher rates of problems with all family members and all types of abuse than the other risk groups. There also were some differences in recent functioning: the high- and medium-risk groups in the alcohol problem domain reported significantly more recent problems with family members, and the high-risk group in the psychiatric problem domain reported somewhat greater rates of recent victimization than the other risk groups. These relationships suggest a link between family history of psychiatric and alcohol problems and present day functioning. These findings are in line with other research indicating vulnerability to abuse and victimization among individuals with mental illness (Gearon, Kaltman, Brown, & Bellack, 2003; Goodman et al., 2001; Teplin et al., 2005) and relationships between maltreatment and a range of poor outcomes, including earlier onset and longer duration of substance abuse, worse physical health, and more interpersonal problems (Goulding et al., 1988; Shäefer & Najavits, 2006; Scott et al., 2010). Individuals with dual diagnosis with multiple family members with histories of psychiatric problems may be especially vulnerable to these sorts of poor outcomes.

There are several clinical implications of these findings. Individuals with dual diagnosis should be asked about their family history in these problem domains, including inquiring about grandparents, parents, and siblings. Those with multiple generations of family members with problems in these domains may be at increased risk for some sort of abuse; clinicians must be on the lookout for these patterns and feel comfortable asking about them, given the evidence that a history of trauma and comorbid substance abuse can negatively impact treatment outcomes (Brown, Recupero, & Stout, 1995; Ouimette, Brown & Najavits, 1998). Importantly, because participants reported on abuse histories but were not asked for details of when or where the abuse took place, these data cannot distinguish between family-based abuse and abuse outside the family. Nevertheless, assessment of abuse is critically important in terms of identifying those with dual diagnosis who may require trauma-informed care as part of their overall mental health and substance abuse treatment services (Silverstein & Bellack, 2008). These data suggest that such assessment may be especially important for those with high-risk family histories. These data also illustrate the extent of negative family relationships among those with dual diagnosis with family histories of substance use and mental health problems, and point to the potential value of family-based interventions as part of substance abuse treatment for this group. An important concern for those in the high-risk groups in the alcohol and drug problem domains is the difficulty of reducing substance use when family members, who may live with the individual or play a role in his/her life, have histories of substance use that could impact the individual’s efforts to reduce or stop using. In addition, those with high family history risk of alcohol problems were more likely to report recent family problems and that family problems were recently discussed with a mental health professional. For many with dual diagnosis, a family history of alcohol problems is relevant to their present day relationships, highlighting the need for attention to family problems within substance abuse treatment for this group.

Overall rates of use of substance abuse or mental health treatment services were high across risk groups in all problem domains. As noted above, the one significant difference among risk groups in recent service use were found in the alcohol problem domain, where the high-risk group was significantly more likely to have recently talked with a professional about alcohol use. While these data do not provide any strong explanation for this finding, it could be that the higher frequency of family history of alcohol problems may serve to increase awareness among probands of the negative effects of alcohol, making them more likely to seek out a professional for advice about their own alcohol problems.

These data illustrate the different patterns and impacts of family history of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems for individuals with dual diagnosis. These patterns raise interesting questions about the single and combined influence of a range of factors - genetics, historical influences, and modeling during childhood, to name a few - that may underlie the impact of family history of problems on relationships and functioning in individuals with dual diagnosis. These findings highlight the possibility that the influence of such factors may build with more affected family members, vary over time, and change from one generation to the next.

This study had a large and well-defined sample, family history data in multiple problem domains, and included multiple generations of relatives in our classification of risk. There were also some limitations. As mentioned above, the sample had high severity of substance use problems, making it hard to find differences by risk group. The data gathered here were self-reports that present potential confounds including cases of poor participant recall and the lack of verification of family relationships and family history information. While participants were instructed to report on biological relatives and to not include adoptive and foster families, inaccuracies are still possible. For example, in the context of substance abuse and relationship difficulties among family members, it is possible that some participants may have unknowingly not been raised by biological parents. While this study relied on self-report, future research may benefit from investigating relationships among family history of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems and interpersonal relationships in samples of probands and family members with verified genetic links. Relatedly, not verifying the reports of family history of alcohol, drug, and psychiatric problems could have resulted in underreporting of problems by probands (Rounsaville et al, 1991), especially for older generations of family members that probands may not have known well. This could in part explain why rates of problems increased substantially in the proband generation - probands may have more information about relatives that are closer to them in age (such as siblings) than they have about relatives from older generations (such as grandparents). It is important, however, to note that rates of missing data were not substantially greater for older versus younger generations - rates of missing data ranged from 5.3-5.6% for grandparents and 2.7-2.9% for siblings – suggesting somewhat but not substantially greater knowledge of siblings than grandparents. In addition, research has shown good reliability and validity of self-reported information by persons with serious mental illness (Bennett, 2009; O’Hare et al., 2001), further supporting the validity of these data. However, collecting data from family members themselves could confirm proband reports and improve accuracy. In addition, we inquired only about problems among relatives and did not assess for formal diagnoses. Further research should use standardized measures, such as the Family History Method (Andreason et al., 1977), to improve diagnostic accuracy. Participants came from only one geographic location with a relatively narrow demographic profile that could impact findings. Issues such as poverty, inner-city residence, or family disintegration could be more or less prevalent in this sample and so could impact these findings. Studies with samples with more geographic and demographic variability could help corroborate and extend the generalizability of the findings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research reported in this manuscript was supported by NIDA grant R01 DA11753 (The Process of Change in Drug Abuse by Schizophrenics, A.S. Bellack PI), NIDA grant RO1 DA 012265 (Behavior Therapy for Substance Abuse in Schizophrenia, A.S. Bellack PI), and NIAAA grant R21 AA014231 (Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorders In Schizophrenia, M.E.

Footnotes

As defined by Lehman et al. (1997): Diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder or other serious mental disorder including bipolar disorder, major depression, or anxiety disorder; for non-schizophrenia diagnoses, individual has worked 25% or less of the past year and/or receives benefits for mental disability.

DISCLOSURES

Ms. Wilson and Drs. Bennett and Bellack report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

REFERENCES

- Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Winkour G. The family history method using diagnostic criteria: Reliability and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1977;34:1129–1235. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770220111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellack AS, Bennett ME, Gearon JS, Brown CH, Yang Y. A randomized clinical trial of a new behavioral treatment for drug abuse in people with severe and persistent mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:426–432. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.426. doi:10.1001/archpsych.63.4.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett ME. Assessment of substance use and substance use disorders in schizophrenia. Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses. 2009;3(1):50–63. doi:10.3371/CSRP.3.1.5. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett ME, Bellack AS, Brown CH, DiClemente C. Substance dependence and remission in schizophrenia and affective disorders. Journal of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:806–814. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.023. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett ME, Bellack AS, Gearon JS. Development of a comprehensive measure to assess clinical issues in dual diagnosis patients: The Substance Use Event Survey for Severe Mental Illness. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:2249–2267. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.012. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Dinwiddie SH, Begleiter H, Crowe RR, Hesselbrock V, Nurnberger JI, Porjesz B, Reich T. Familial transmission of substance dependence: Alcohol, marijuana, cocaine and habitual smoking. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:982–988. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.982. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd SJ, Plemons BW, Schwartz RP, Johnson JL, Pickens RW. The relationship between parental history and substance use severity in drug treatment patients. American Journal on Addictions. 1999;8:15–23. doi: 10.1080/105504999306045. doi: 10.1080/105504999306045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Recupero PR, Stout R. PTSD substance abuse co-morbidity and treatment utilization. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:251–254. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00060-3. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(94)00060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor-Graae E, Norstrom LG, McNeil TF. Substance abuse in schizophrenia: A review of the literature and a study of correlates in Sweden. Schizophrenia Research. 2001;48:69–82. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00114-6. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(00)00114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Cocco KM, Correia CJ. Reliability and validity of the Addiction Severity Index among outpatients with severe mental illness. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9(4):422–428. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.9.4.422. [Google Scholar]

- Comptois KA, Tisdall WA, Holdcraft LC, Simpson T. Dual diagnosis: Impact of family history. The American Journal on Addictions. 2005;14:291–299. doi: 10.1080/10550490590949479. doi:10.1080/10550490590949479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coviello DM, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Rutherford MJ, Zanis DA. The role of family history in addiction severity treatment and response. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;26:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00143-0. doi:10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis L, Uezato A, Newell JM, Frazier E. Major depression and comorbid substance use disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2008;21:14–18. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f32408. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f32408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L. Dual diagnosis of substance use in schizophrenia: Prevalence and impact on outcomes. Schizophrenia Research. 1999;35:S93–S100. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00161-3. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(98)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearon JS, Kaltman SI, Brown C, Bellack AS. Traumatic life events and PTSD among women with substance use disorders and schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54(4):523–528. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.523. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Salyers MP, Mueser KT, Rosenberg SD, Swartz M, Essock SM, 5 Site Health and Risk Study Research Committee Recent victimization in women and men with severe mental illness: Prevalence and correlates. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14(4):615–632. doi: 10.1023/A:1013026318450. doi: 10.1023/A:1013026318450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulding JM, Stein JA, Siegel JM, Burnam MA, Sorenson SB. Sexual assault history and use of mental health services. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1988;16(5):625–644. doi: 10.1007/BF00930018. doi:10.1007/BF00930018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins DC, el-Guebaly N. More data on the Addiction Severity Index: Reliability & validity with the mentally ill substance abuser. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1992;180:197–201. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199203000-00009. doi:10.1097/00005053-199203000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RM, Lichtenstein P, Grann M, Längström N, Fazel S. Alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia: a national cohort study of 12,653 patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;72(6):775–779. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06320. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Davis CG, Kessler RC. The familial aggregation of common psychiatric and substance use disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey: A family history study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;170:541–548. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.6.541. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.6.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Myers CP, Corty E, Thompson JW. Prevalence and patterns of “dual diagnosis” among psychiatric inpatients. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1994;35(2):106–112. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(94)90054-l. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(94)90054-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Dixon LB, Kernan E, DeForge BR, Postrado LT. A randomized trial of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:1038–1043. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230076011. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230076011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J. Dual diagnosis: Co-morbidity of severe mental illness and substance abuse. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 1998;9(1):9–15. doi:10.1080/09585189808402176. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Alterman AI, Cacciola J, Metzger D, O’Brien CP. A new measure of substance abuse treatment. Initial studies of the treatment services review. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1992;180(2):101–110. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199202000-00007. doi:10.1097/00005053-199202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grisson G, Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Use Treatment. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. doi:10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Stolar M, Stevens DE, Goulet J, Preisig MA, Fenton B, Rounsaville S. Familial transmission of substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:973–979. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.973. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne BJ, Caspi A, Harrington H, Poulton R, Rutter M, Moffitt TE. Predictive value of family history on severity of illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66(7):738–747. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.55. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Corbin WR, Sinha R, O’Malley SS. Parental history of anxiety and alcohol-use disorders and alcohol expectancies as predictors of alcohol-related problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(2):227–236. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare T, Cutler J, Sherrer MV, McCall TM, Dominique KN, Garlick K. Co-occurring psychosocial distress and substance abuse in community clients: Initial validity and reliability of self-report measures. Community Mental Health Journal. 2001;37(6):481–487. doi: 10.1023/a:1017522011729. doi:10.1023/A:1017522011729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette PC, Brown PJ, Najavits LM. Course and treatment of patients with both substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23(6):785–795. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00064-1. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickens RW, Preston KL, Miles DR, Gupman AE, Johnson EO, Newlin DB, Umbricht A. Family history influence on drug abuse severity and treatment outcome. Journal of Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;61:261–270. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00146-0. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BJ, Penick EC, Othmer E, Bingham SF, Rice AS. Prevalence of additional psychiatric syndromes among male alcoholics. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1982;43(10):404–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiger DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264:2511–2518. doi:10.1001/jama.264.19.2511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Kosten TR, Weissman MM, Prusoff B, Pauls D, Anton SF, Merikangas K. Psychiatric disorders in relatives of probands with opiate addiction. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:33–42. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250035004. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford MJ, Metzger DS, Alterman AI. Parental relationships and substance use among methadone patients: The impact on levels of psychological symptomatology. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1994;11(5):415–423. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)90094-9. doi:10.1016/0740-5472(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäefer I, Najavits LM. Clinical challenges in the treatment of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and substance abuse. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007;20(6):614–618. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f0ffd9. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f0ffd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JM, Smith DR, Ellis P. Prospectively ascertained child maltreatment and its association with DSM-IV mental disorders in young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(7):712–719. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.71. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein SM, Bellack AS. A scientific agenda for the concept of recovery as it applies to schizophrenia. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(7):1108–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.004. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Weiner DA. Crime victimization in adults with severe mental illness: Comparison with the National Crime Victimization Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;62(8):911–921. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.911. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanis DA, McLellan AT, Corse S. Is the Addiction Severity Index a reliable and valid assessment instrument among clients with severe and persistent mental illness and substance abuse disorders? Community Mental Health Journal. 1997;33(3):213–227. doi: 10.1023/a:1025085310814. doi:10.1023/A:1025085310814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]