A systematic review of publications from 1990–2012 regarding anaplastic large cell lymphoma and breast implantation to see if implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma may be a distinct entity is reported.

Keywords: Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, Breast implant, Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

Learning Objectives

Describe the spectrum of diseases, represented by CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs), that can give rise to a reactive process.

Discuss the favorable prognoses of reactive CD30+ LPDs and how they do not therefore require aggressive therapy.

Explain how implant-associated ALCL (iALCL) follows Hanahan and Weinberg's principles and acquires the ability to metastasize with new mutations.

Abstract

CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders represent a spectrum of diseases with distinct clinical phenotypes ranging from reactive conditions to aggressive systemic anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)− anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). In January 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced a possible association between breast implants and ALCL, which was likened to systemic ALCL and treated accordingly. We analyzed existing data to see if implant-associated ALCL (iALCL) may represent a distinct entity, different from aggressive ALCL. We conducted a systematic review of publications regarding ALCL and breast implantation for 1990–2012 and contacted corresponding authors to obtain long-term follow-up where available. We identified 44 unique cases of iALCL, the majority of which were associated with seroma, had an ALK− phenotype (97%), and had a good prognosis, different from the expected 40% 5-year survival rate of patients with ALK− nodal ALCL (one case remitted spontaneously following implant removal; only two deaths have been reported to the FDA or in the scientific literature since 1990). The majority of these patients received cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone with or without radiation, but radiation alone also resulted in complete clinical responses. It appears that iALCL demonstrates a strong association with breast implants, a waxing and waning course, and an overall good prognosis, with morphology, cytokine profile, and biological behavior similar to those of primary cutaneous ALCL. Taken together, these data are suggestive that iALCL may start as a reactive process with the potential to progress and acquire an aggressive phenotype typical of its systemic counterpart. A larger analysis and prospective evaluation and follow-up of iALCL patients are necessary to definitively resolve the issue of the natural course of the disease and best therapeutic approaches for these patients.

Implications for Practice:

Breast implant – associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (iALCL) is a relatively new and rare entity. Since it was first described in the 1990s it has been treated with aggressive therapies, similar to cutaneous lymphomas until they were designated to their own treatment category. This review demonstrates the similarities of iALCL to primary cutaneous ALCL by its good prognosis, biologic behavior, morphology, and relapsing nature. A larger analysis with prospective evaluation and follow-up of iALCL patients is necessary to definitively resolve the issue of the natural course and best therapeutic approaches for these patients. Less aggressive therapeutic options may be used in the future but this cannot be recommended without further investigation and clinical trials.

Introduction

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a rare CD30+ T-cell lymphoma among a spectrum of CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). Primary systemic ALCL (PSALCL) represents approximately 2%–3% of all non-Hodgkin's lymphomas in adults [1, 2]. Based on expression of the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) protein, this lymphoma can be further subdivided into ALK− and ALK+ lymphoma. Historically, patients with ALK− ALCL have had a more aggressive disease course, with an overall 5-year survival rate of approximately 40% despite aggressive therapies, compared with patients with ALK+ ALCL who have a survival rate of 80% [3].

Primary cutaneous ALCL (PCALCL) is almost exclusively an ALK− lymphoma that, in contrast to its systemic counterpart, follows a rather indolent and relapsing course, is associated with an overall 5-year survival rate greater than 90%, and is usually treated conservatively with a single agent, such as methotrexate or radiation [4]. The majority of PCALCL cases present as solitary or localized skin nodules or tumors that often spontaneously regress and may recur over time. Many cases are thought to be a reactive process in the skin as opposed to a true lymphoma [5].

In January 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced a possible association between saline and silicone breast implants and ALCL, which has been likened to systemic ALCL and treated accordingly, with multiagent chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy. Since the first case of ALCL in proximity to a breast implant was published in 1997 [6], there have been more than 60 unique reports of primary breast lymphoma (PBL) associated with implants, greater than 90% of which have been of T-cell origin [7]. This is unexpected because PBL is extremely rare, accounting for only up to 0.5% of all breast cancers, with the great majority, more than 80% of nonimplant-associated PBLs, being of B-cell origin [8]. However, this seemingly surprising finding may indicate an immunologic derivation of this rare malignancy. The mammary gland develops from the surface ectoderm [9] and shares common properties with the skin and skin appendages, including its immune system. Understanding of cutaneous immunity may shed light on immune-mediated processes in the breast.

It is well established that skin injury triggers innate immune responses, resulting in the release of various cytokines and chemokines from keratinocytes and skin-resident immune cells, creating a proinflammatory environment. This leads to recruitment of other immune cells, such as dendritic cells, capable of stimulating naïve T cells in the draining lymph nodes, making them antigen-specific effector memory cells capable of traveling back to the original site of inflammation (adaptive immune response) [10]. Chronic antigenic and inflammatory stimulation leads to constitutive recruitment of these memory T cells to the site and their further proliferation and expansion, and, eventually, may lead to natural selection of a clone with survival advantages and establishment of malignancy [11].

The CD30 antigen is a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily, which is normally expressed by CD45RO+ activated memory T cells [12]. CD30 overexpression is observed in a number of inflammatory, infectious, and autoimmune conditions [13]. Chronic inflammation instigates the development of a malignant clone by numerous mechanisms, including induction of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, epigenetic modulation of chromatin, and microRNA instability, among others [11]. Chronic inflammation stimulates abnormal induction of CD30, which, combined with TNF-α overproduction [14] as well as the chromosomal and microsatellite instability found in the CD30+ cells, may be directly related to induction of CD30+ LPDs and play a role in disease progression [15].

In the same way, chronic inflammation in the skin is thought to play a role in the induction of cutaneous lymphomas [10]. It has long been established that reactive cutaneous CD30+ LPDs, such as lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP), can give rise to overt CD30-expressing malignancies [16]. It is hypothesized that the mysterious resistance of benign or indolent CD30+ cutaneous lymphoid proliferations, such as LyP and PCALCL, after successful chemotherapy for Burkitt's lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia may be a result of the presence of a chemotherapy-resistant stem cell [17]. Relapse rates for patients with PCALCL after treatment with multiagent chemotherapy, such as cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP), are in the range of 62%–71% [18]. Importantly, these do not represent progression to systemic disease and do not change the overall excellent prognosis of patients with these indolent cutaneous proliferations [19]. Similarly to LyP and PCALCL, some implant-associated ALCL (iALCL) cases relapse after aggressive chemotherapies, most without further progression to aggressive and metastatic disease, demonstrating a course similar to that of patients with PCALCL.

CD30+ cutaneous lymphoma has been reported in association with arthropod bites [20], pseudolymphomas [21], and metallic orthopedic implants [22], whereas cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs) have been noted in association with breast implants [23] and other foreign objects. We observed a case of Sezary syndrome, a leukemic form of CTCL, which was induced by a penile prosthesis (unpublished personal observation by L.G.). The disease completely resolved after removal of the prosthesis. Similarly, in patients with iALCL, the presence of an implant, especially in cases with textured implants or possible contamination with certain bacterial fragments (such as small portions of the bacterial wall, capable of stimulating toll-like receptors on immune cells), inciting strong immune responses [11], may initiate and maintain chronic inflammatory responses.

Our review of the published literature suggests that iALCL may arise as a reactive entity with an indolent course and favorable outcome, different from the systemic counterpart. However, with time and constant antigenic stimulation, multiple oncogenic mutations may accumulate in T cells in a stepwise fashion during the process of somatic evolution.

Our review of the published literature suggests that iALCL may arise as a reactive entity with an indolent course and favorable outcome, different from the systemic counterpart. However, with time and constant antigenic stimulation, multiple oncogenic mutations may accumulate in T cells in a stepwise fashion during the process of somatic evolution. The dominant malignant clone that has a competitive advantage over cells that have not acquired the same characteristics of cancer, including an ability to invade and metastasize, is self-selected. At this point, iALCL behaves similarly to aggressive CD30+ systemic lymphoma. The difference between the localized and metastatic forms probably has clinical significance because an indolent local disease may require conservative therapeutic approaches, in contrast to the metastatic form. Although the data on iALCL are sparse and no definitive conclusions can be drawn, we desired to initiate a thought-provoking discussion bringing to light numerous similarities in the natural course of localized iALCL and PCALCL and to propose a potential pathway for iALCL pathogenesis.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the scientific literature for all publications relating to ALCL and breast implantation using the PubMed, Embase, FDA, and Web of Knowledge databases for 1990–2012. Search methods, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data to be extracted from publications were specified in a protocol prior to study commencement. For each database, we used the following keyword search method: (breast implantation) AND (lymphoma) OR (anaplastic large cell lymphoma). This search was followed by: (prosthesis) AND (lymphoma) OR (anaplastic large cell lymphoma). When available, we applied filters to narrow our search to human-based and English language publications.

Two independent researchers (S.S. and M.S.) reviewed the resulting search data for studies meeting the protocol criteria. Inclusion criteria included publications and abstracts that pertained to both ALCL and breast implantations. We excluded foreign language publications, reviews, and publications that included repeat cases. Data extracted from the publications included patient age, type of implant, time from implant to ALCL diagnosis, ALK status, presenting symptoms, treatments, responses to therapy, implantation removal, long-term follow-up, lymphadenopathy, the presence of systemic disease, and survival outcomes. Corresponding authors for all publications were contacted for updated information regarding long-term patient follow-up.

Results

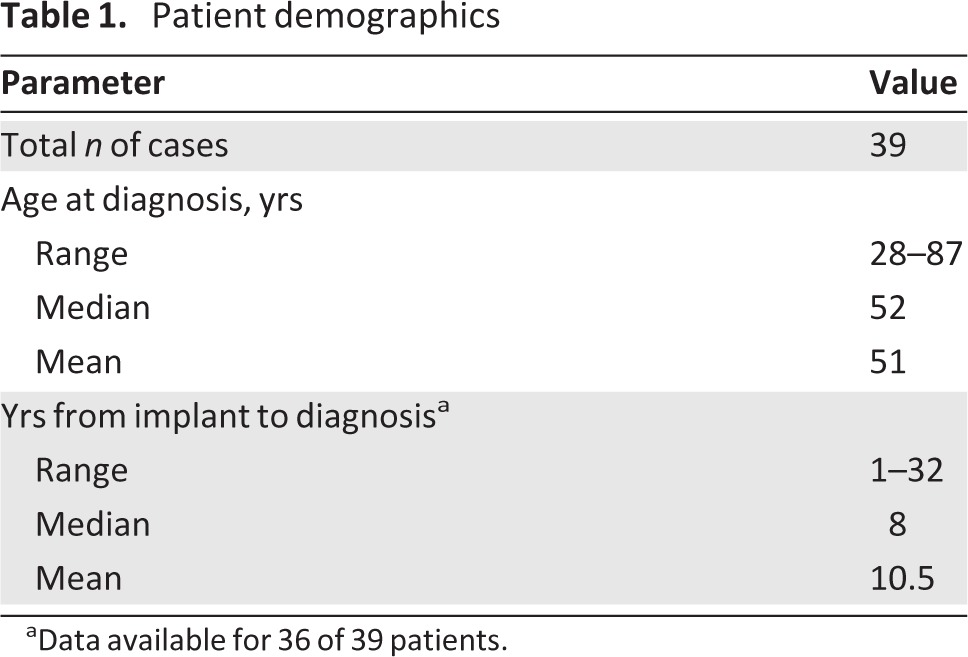

We identified 23 case reports describing 44 unique patients with ALCL in proximity to saline or silicone gel implants (Table 1). We excluded five patients from this analysis because of insufficient information available (abstract only), leaving 39 cases for review [1, 3, 6, 24–39]. All patients had a pathologic diagnosis of ALCL. Of these, the ALK status was available in 36 cases. Thirty-five (97%) of these 36 patients were ALK−. The one patient with an ALK+ biopsy was initially ALK−, but repetitive testing proved to be ALK+ on two subsequent evaluations [36].

Table 1.

Patient demographics

aData available for 36 of 39 patients.

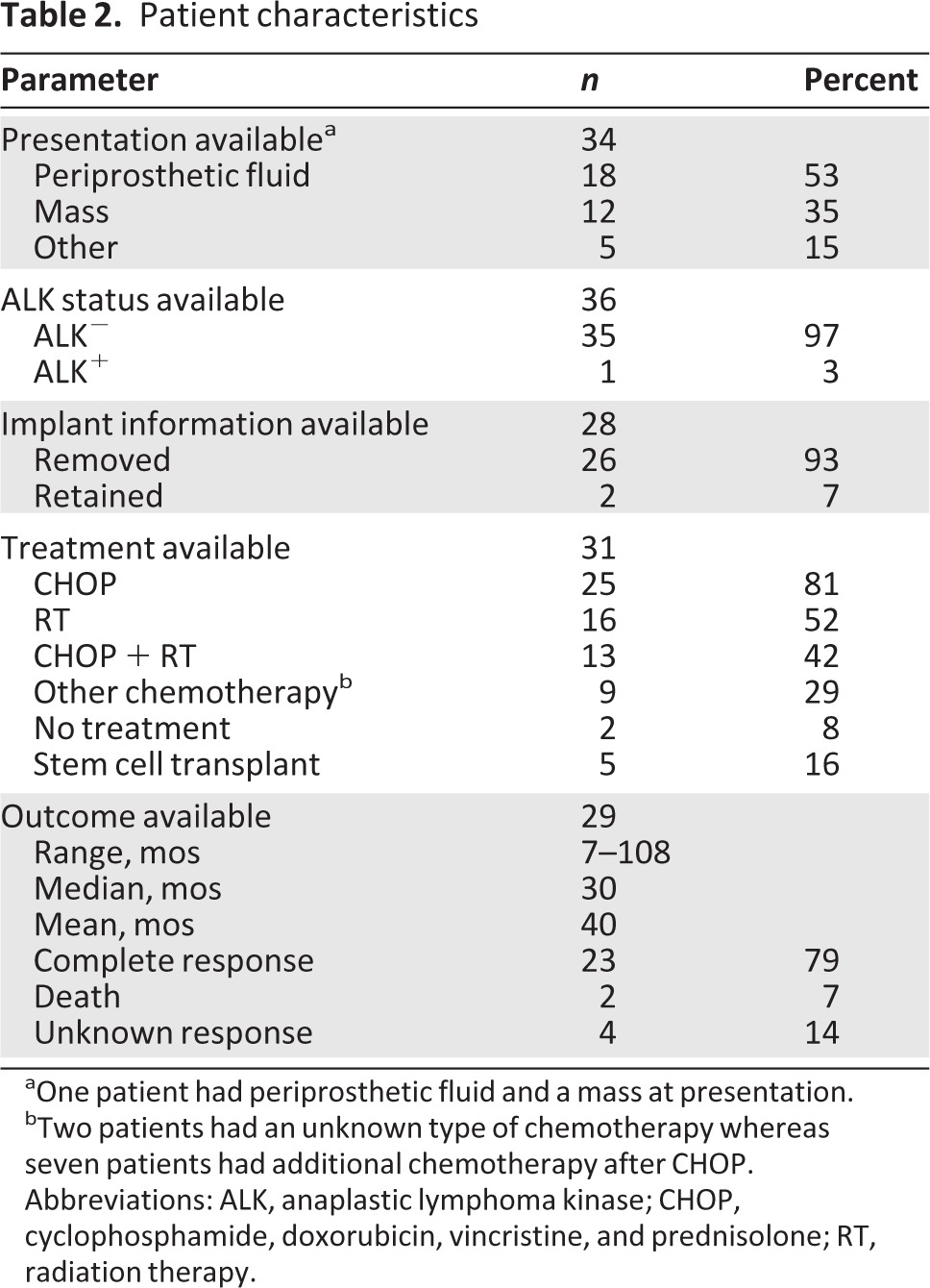

Available patient characteristics and information regarding their presentation, treatment, and outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Patient age was in the range of 28–87 years, with a median age of 51 years at the time of diagnosis. Presenting symptoms were available for 34 patients, the most common of which was swelling of the affected breast, which was associated with pain in some patients. Of these, 18 (53%) were found to have late periprosthetic fluid collection (>1 year from implantation), while 12 (35%) had a palpable mass. One patient reportedly had both a fluid collection and a mass at presentation. Two patients (6%) presented with pain alone and were found to have capsular contractions. Seven of 31 (23%) patients for whom data were available had lymph node involvement at the time of diagnosis; one patient had pleural thickening and anterior chest wall involvement, while another was found to have thoracolumbar spine and lung metastasis following her first round of CHOP therapy. Long-term follow-up was available for 20 patients, with a range of 7–108 months and a median of 30 months (Fig. 1). The corresponding authors were contacted and 10 provided additional data to what was previously published (response rate, 50%).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

aOne patient had periprosthetic fluid and a mass at presentation.

bTwo patients had an unknown type of chemotherapy whereas seven patients had additional chemotherapy after CHOP.

Abbreviations: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone; RT, radiation therapy.

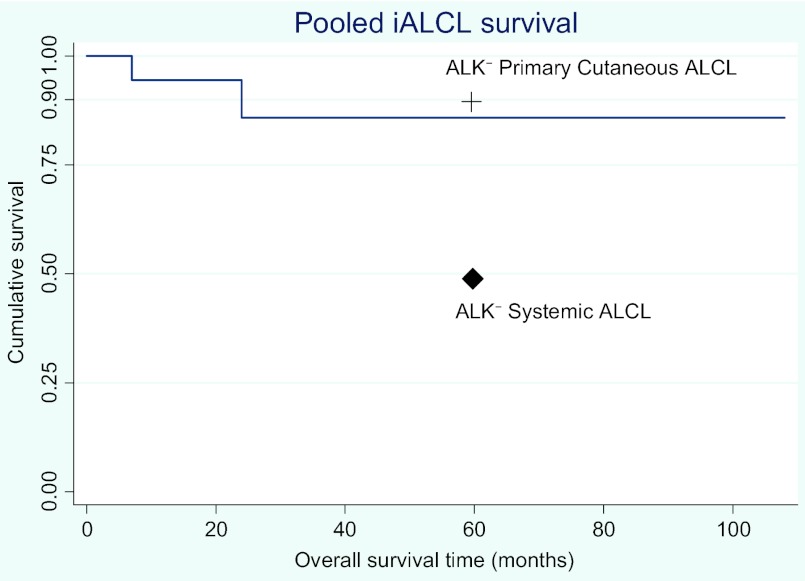

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve of 18 iALCL patients with survival data available. 5-year survival probabilities for patients with other ALK− ALCLs are plotted for comparison [3, 41].

Abbreviations: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; iALCL, implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

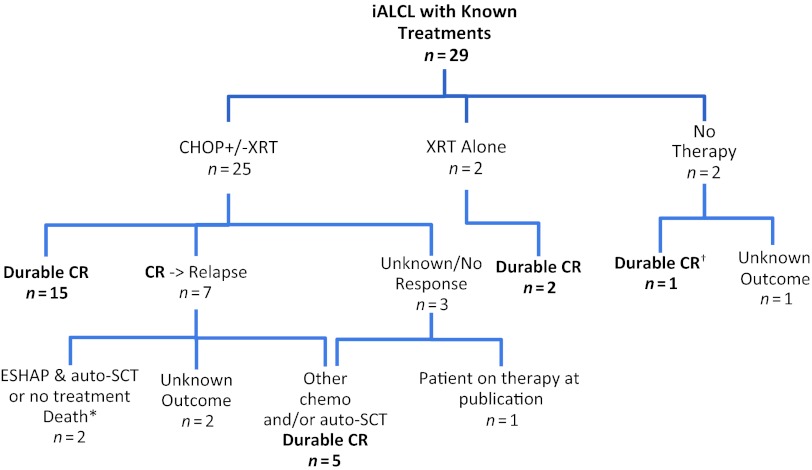

Information on treatment was available for 31 of the 39 cases reviewed (Fig. 2). Breast implants were removed in the vast majority of patients for whom such information was available (26 of 28 patients, 93%). The most frequently used therapy was CHOP, in 25 of 31 (81%) patients. Fifteen (48%) patients underwent radiation therapy, 13 of whom did so in conjunction with CHOP. Two patients had chemotherapy of an unknown type with no evidence of disease (NED) 24 months and 30 months after treatment. Two patients had no treatment other than implant removal; on follow-up, one of them was alive with NED 20 months after surgery. One patient had radiation alone and was alive with NED 10 months after completion of treatment.

Figure 2.

Treatments and outcomes in patients with available data (29 or 39) with an overall response rate to treatment of 79% (23 or 29).

†No therapy other than removal of implant alone.

*One patient had no further treatment after CHOP, one had ESHAP and auto-SCT prior to death.

Abbreviations: auto-SCT, autologous stem cell transplant; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone; CR, complete response; ESHAP, etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, and cisplatin; iALCL, implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma; XRT, radiation therapy.

Of the patients treated with CHOP (n = 25), the majority (n = 15, 60%) had a complete response (CR) to initial therapy that was durable and did not require additional treatment. Follow-up was in the range of 9–108 months. Seven patients (28%) initially responded but relapsed soon after therapy was stopped. They were retreated with various multiagent chemotherapeutic regimens, including ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE); etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, and cisplatin; gemcitabine, ifosfamide, and vinorelbine; and autologous stem cell transplantation (auto-SCT), leading to an additional five CRs (20%). Two patients (9%) did not respond to initial CHOP treatment and were retreated with ICE, with a CR, although only 8 months of follow-up were available for one patient. Of the four patients who received auto-SCT, three had a CR and NED at 2 years, 6 years, and 7.5 years after diagnosis; the third patient had progressive disease and died. One patient relapsed following CHOP, had no further treatment, and died 7 months after diagnosis. There was no follow-up available for eight patients.

Two patients had no treatment other than removal of their implant and capsule, one of whom was disease free 20 months after diagnosis. Follow-up is not available for the other patient. One of the two patients who retained their implants received CHOP plus radiation therapy and was alive with NED 8 years after diagnosis until she was lost to follow-up; the other has no follow-up records available.

Discussion

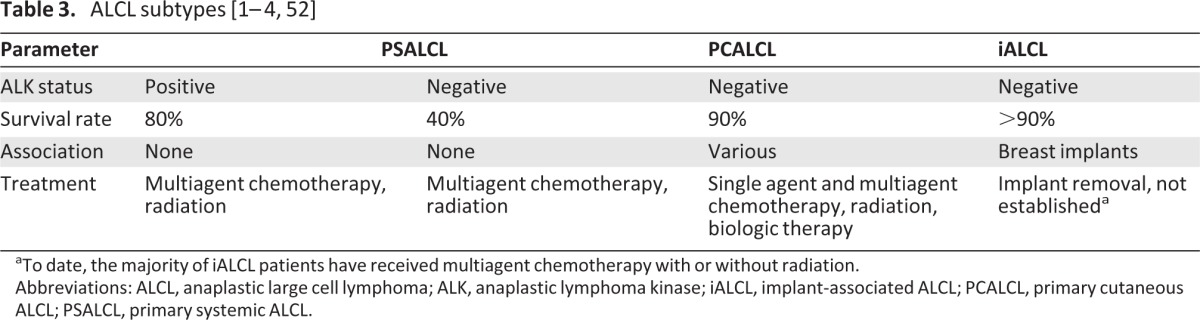

ALK status predicts vastly different outcomes for affected patients with PSALCL and PCALCL. Systemic ALK− ALCL is associated with a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 40%, versus 90% in patients with ALK− PCALCL (Table 3). iALCL was found to be 100% ALK− in one previous study, whereas only 37% (10 of 27) of patients with breast ALCL without implants had ALK− lymphoma [40]. Our expanded dataset of 39 cases of iALCL occurring in women with breast implants confirmed that the vast majority of these patients (97%) have ALK− disease.

Table 3.

aTo date, the majority of iALCL patients have received multiagent chemotherapy with or without radiation.

Abbreviations: ALCL, anaplastic large cell lymphoma; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; iALCL, implant-associated ALCL; PCALCL, primary cutaneous ALCL; PSALCL, primary systemic ALCL.

Survival data and long-term follow-up were inconsistently reported throughout the case reports. Recognizing the limitations of our analysis, no definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding survival times. However, in 18 cases for which outcomes and survival times were documented, nine patients were alive and disease free for 40–108 months and seven patients were alive and disease free with only short-term follow-up available (≤30 months). There have been two reported deaths in association with iALCL. Both those patients had involvement beyond the primary site at the time of diagnosis, including nodal and systemic involvement. Based on the available data, the survival rate of patients with localized iALCL is 100%, with a median follow-up duration of 38 months, which is much better than expected for patients with ALK−negative systemic ALCL.

A recent study by Kadin et al. [41] compared several aspects of iALCL and PCALCL cells, including gene expression and cytokine profiles. They found that these two diseases were similar in their morphologies and cytokine profiles and distinctly different from other CTCLs. They also found that the cytokines produced by these tumor cells were more representative of the Th17 type, which is classically associated with inflammation, further supporting the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of iALCL.

Furthermore, PCALCL has been reported in association with various agents, and in some cases clearly presents a reactive phenomenon. Similar to iALCL, PCALCL is an ALK− cutaneous ALCL, an indolent malignancy with a relapsing and remitting course despite systemic therapies, and in some cases spontaneous regression. True malignant transformation of PCALCL is possible, resulting from chronic antigenic stimulation [20–22]. In this respect, the high incidence of late onset periprosthetic fluid formation in iALCL patients is intriguing, especially when compared with the incidence found in the overall breast implant population. Fifteen of 29 (52%) cases for which data were available reported periprosthetic fluid formation as a part of the presentation, whereas studies have reported an incidence of 0.05–0.1 after any breast augmentation [34]. The causal relationship between ALCL and seroma formation is unclear. Seroma may form as a result of chronic inflammation or secondary to malignant transformation of cells. In any case, the presence of late onset seroma is a warning sign, and further investigation into its etiology should be initiated immediately [42]. Interestingly, PCALCL is known to relapse frequently (62%–71%) [18] in patients treated with traditional chemotherapy, such as CHOP, but a relapse does not predict a worse outcome [43]. Moreover, a conventional multiagent chemotherapy regimen does not have a higher cure rate nor does it prevent future relapses, when compared with single-agent therapies in patients with PCALCL [44]. Similarly to PCALCL patients, 23% of the iALCL cases had relapses and underwent additional treatment, without a change in the disease course or outcome. In cases for which data were available, we observed a >80% durable CR rate in patients with iALCL treated with various therapies as well as spontaneous resolution of the lymphoma without additional therapy, other than removal of the implant. It is widely accepted that malignant transformation involves the accumulation of somatic mutations that favors growth of a specific clone, with thousands of mutations detected in a malignant cell population, especially of lymphoid origin [45, 46]. Even in the absence of genomic instability, extensive cell proliferation together with selection for a mutant phenotype can lead to the accumulation of somatic mutations for malignant transformation [47–50]. The primary stimulus to cell proliferation may eventually result in cancer. It is conceivable that the persistent external stimulus associated with a breast implant is a primary “event” that is followed by additional mutations that give selective growth advantages in a minority of patients with breast implants. The likelihood of this stepwise process resulting in overt life-threatening malignancy is low, explaining the low rate of lymphomas associated with breast implants and other foreign bodies. It is possible that mutations continue to accumulate in originally reactive lymphocytic infiltrate, resulting in progression of the disease from low-grade malignancy with an excellent prognosis to aggressive lymphoma.

It is conceivable that the persistent external stimulus associated with a breast implant is a primary “event” that is followed by additional mutations that give selective growth advantages in a minority of patients with breast implants. The likelihood of this stepwise process resulting in overt life-threatening malignancy is low, explaining the low rate of lymphomas associated with breast implants and other foreign bodies.

Our analysis revealed that localized iALCL may represent a distinctive subset of the CD30+ LPDs, similar to PCALCL. There are several unique features of localized iALCLs that set them apart from systemic ALCL. (a) The combination of a strong association with trauma or a foreign object (breast implant) with spontaneous remissions reported after removal of the implant are suggestive of a reactive component. (b) Patients have a relapsing course after multiagent chemotherapy but retain their good prognosis despite their ALK− status, not unlike PCALCL patients. (c) They are similar in morphology and cytokine profile to PCALCLs while distinctly different from other CTCLs [41].

Hanahan and Weinberg's [51] principles indicate that tumor progression happens via a process analogous to Darwinian evolution, whereby each consequent genetic change provides a growth advantage to the cell. Although a number of associations of foreign objects and ALK− ALCLs are reported in humans, surprisingly, there are no animal models for the disease. iALCL may represent a unique opportunity to study the induction and progression of ALCL. The difference between the localized and metastatic forms probably has clinical significance because a less aggressive local disease may require conservative therapeutic approaches, in contrast to the metastatic form. We conclude that iALCL warrants further consideration and investigation, not only clinically but also biologically.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by SPORE NIH 5P50CA121973–03 Project 5 and by grant number UL1 RR024153 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) to L.G.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Larisa J. Geskin, Sara K. Story

Provision of study material or patients: Sara K. Story

Collection and/or assembly of data: Sara K. Story, Michael K. Schowalter

Data analysis and interpretation: Larisa J. Geskin, Sara K. Story, Michael K. Schowalter

Manuscript writing: Larisa J. Geskin, Sara K. Story, Michael K. Schowalter

Final approval of manuscript: Larisa J. Geskin, Sara K. Story, Michael K. Schowalter

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Section editor: George P. Canellos: Celgene Business Advisory Board (C/A)

Reviewer “A”: Biogen Idec, Seattle Genetics, Genentech, Sigma Tau (C/A)

Reviewer “B”: None

Reviewer “C”: None

C/A: Consulting/advisory relationship; RF: Research funding; E: Employment; H: Honoraria received; OI: Ownership interests; IP: Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; SAB: scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Bishara MR, Ross C, Sur M. Primary anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the breast arising in reconstruction mammoplasty capsule of saline filled breast implant after radical mastectomy for breast cancer: An unusual case presentation. Diagn Pathol. 2009;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim B, Roth C, Chung KC, et al. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma and breast implants: A systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2141–2150. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182172418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong AK, Lopategui J, Clancy S, et al. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma associated with a breast implant capsule: A case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1265–1268. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318162bcc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo DK, Jones CR, Vanoli-Storz MN, et al. Prognostic factors in primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: Characterization of clinical subset with worse outcome. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:667–674. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. J Clin Oncol; Report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House; November 1997; Virginia. 1999. p. 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keech JA, Jr, Creech BJ. Anaplastic T-cell lymphoma in proximity to a saline-filled breast implant. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:554–555. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199708000-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazzeri D, Agostini T, Bocci G, et al. ALK-1-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma associated with breast implants: A new clinical entity. Clin Breast Cancer. 2011;11:283–296. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joks M, Myśliwiec K, Lewandowski K. Primary breast lymphoma—a review of the literature and report of three cases. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:27–33. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.20600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikkola ML, Millar SE. The mammary bud as a skin appendage: Unique and shared aspects of development. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2006;11:187–203. doi: 10.1007/s10911-006-9029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kupper TS, Fuhlbrigge RC. Immune surveillance in the skin: Mechanisms and clinical consequences. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:211–222. doi: 10.1038/nri1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowe DB, Storkus WJ. Chronic inflammation and immunologic-based constraints in malignant disease. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:1265–1274. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis TM, Simms PE, Slivnick DJ, et al. CD30 is a signal-transducing molecule that defines a subset of human activated CD45RO+ T cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:2380–2389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadin ME. Regulation of CD30 antigen expression and its potential significance for human disease. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1479–1484. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65018-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Y, Zhou BP. TNF-α/NF-κB/Snail pathway in cancer cell migration and invasion. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:639–644. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levi E, Wang Z, Petrogiannis-Haliotis T, et al. Distinct effects of CD30 and Fas signaling in cutaneous anaplastic lymphomas: A possible mechanism for disease progression. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1034–1040. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis TH, Morton CC, Miller-Cassman R, et al. Hodgkin's disease, lymphomatoid papulosis, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma derived from a common T-cell clone. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1115–1122. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204233261704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gniadecki R. Neoplastic stem cells in cutaneous lymphomas: Evidence and clinical implications. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1156–1160. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.9.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: Lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024–4035. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-351346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akilov OE, Pillai RK, Grandinetti LM, et al. Clonal T-cell receptor β-chain gene rearrangements in differential diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis from skin metastasis of nodal anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:943–947. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamant L, Pileri S, Sabattini E, et al. Cutaneous presentation of ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma following insect bites: Evidence for an association in five cases. Haematologica. 2010;95:449–455. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.015024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergman R. Pseudolymphoma and cutaneous lymphoma: Facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palraj B, Paturi A, Stone RG, et al. Soft tissue anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma associated with a metallic orthopedic implant: Case report and review of the current literature. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:561–564. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duvic M, Moore D, Menter A, et al. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in association with silicone breast implants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:939–942. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alobeid B, Sevilla DW, El-Tamer MB, et al. Aggressive presentation of breast implant-associated ALK-1 negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma with bilateral axillary lymph node involvement. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:831–833. doi: 10.1080/10428190902795527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carty MJ, Pribaz JJ, Antin JH, et al. A patient death attributable to implant-related primary anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:112e–118e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318221db96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Jong D, Vasmel WJ, de Boer JP, et al. Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in women with breast implants. JAMA. 2008;300:2030–2035. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Do V, Shifrin DA, Oostendorp L. Lymphoma of the breast capsule in a silicone implant-reconstructed patient. Am Surg. 2010;76:1030–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farkash EA, Ferry JA, Harris NL, et al. Rare lymphoid malignancies of the breast: A report of two cases illustrating potential diagnostic pitfalls. J Hematop. 2009;2:237–244. doi: 10.1007/s12308-009-0043-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fritzsche FR, Pahl S, Petersen I, et al. Anaplastic large-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the breast in periprosthetic localisation 32 years after treatment for primary breast cancer—a case report. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:561–564. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaudet G, Friedberg JW, Weng A, et al. Breast lymphoma associated with breast implants: Two case-reports and a review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:115–119. doi: 10.1080/10428190210189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gualco G, Chioato L, Harrington WJ, Jr, et al. Primary and secondary T-cell lymphomas of the breast: Clinico-pathologic features of 11 cases. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2009;17:301–306. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e318195286d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li S, Lee AK. Silicone implant and primary breast ALK1-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma, fact or fiction? Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;3:117–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miranda RN, Lin L, Talwalkar SS, et al. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma involving the breast: A clinicopathologic study of 6 cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1383–1390. doi: 10.5858/133.9.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newman MK, Zemmel NJ, Bandak AZ, et al. Primary breast lymphoma in a patient with silicone breast implants: A case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:822–825. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olack B, Gupta R, Brooks GS. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma arising in a saline breast implant capsule after tissue expander breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59:56–57. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31804d442e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Popplewell L, Thomas SH, Huang Q, et al. Primary anaplastic large-cell lymphoma associated with breast implants. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52:1481–1487. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.574755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roden AC, Macon WR, Keeney GL, et al. Seroma-associated primary anaplastic large-cell lymphoma adjacent to breast implants: An indolent T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:455–463. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3801024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sahoo S, Rosen PP, Feddersen RM, et al. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma arising in a silicone breast implant capsule: A case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:e115–e118. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-e115-ALCLAI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong A, Subtil A. Secondary cutaneous involvement by breast implant-associated ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL)—report of a case with fatal outcome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:423. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lazzeri D, Agostini T, Pantaloni M, et al. Further information on anaplastic large cell lymphoma and breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:813–815. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318222158b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kadin ME, Xu H, Pavlov I, et al. Breast implant associated ALCL closely resembles primary cutaneous ALCL. Lab Investig. 2012;92(suppl 1):346A. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bengtson B, Brody GS, Brown MH, et al. Late Periprosthetic Fluid Collection after Breast Implant Working Group. Managing late periprosthetic fluid collections (seroma) in patients with breast implants: A consensus panel recommendation and review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:1–7. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318217fdb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shehan JM, Kalaaji AN, Markovic SN, et al. Management of multifocal primary cutaneous CD30 anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bekkenk MW, Geelen FA, van Voorst Vader PC, et al. Primary and secondary cutaneous CD30(+) lymphoproliferative disorders: A report from the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Group on the long-term follow-up data of 219 patients and guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 2000;95:3653–3661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nowell PC. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976;194:23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.959840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. The multistep nature of cancer. Trends Genet. 1993;9:138–141. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90209-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chow M, Rubin H. Clonal selection versus genetic instability as the driving force in neoplastic transformation. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6510–6518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Preston-Martin S, Pike MC, Ross RK, et al. Increased cell division as a cause of human cancer. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7415–7421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomlinson I, Bodmer W. Selection, the mutation rate and cancer: Ensuring that the tail does not wag the dog. Nat Med. 1999;5:11–12. doi: 10.1038/4687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tomlinson IP, Novelli MR, Bodmer WF. The mutation rate and cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14800–14803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Querfeld C, Khan I, Mahon B, et al. Primary cutaneous and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma: Clinicopathologic aspects and therapeutic options. Oncology. 2010;24:574–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]