Motivations and other variables influencing patients in their decision to participate in phase I oncology trials were investigated.

Keywords: Phase I, Oncology, Enrollment, Trial participation, Patient

Abstract

Introduction.

For anticancer drug development, it is crucial that patients participate in early-phase clinical trials. The main aim of this study was to gain insight into the motivations and other variables influencing patients in their decision to participate in phase I oncology trials.

Materials and Methods.

Over a period of 25 months, all patients who were informed about (specific) phase I trials in our cancer center were retrospectively included in this study. Data on providing informed consent and final phase I enrollment were collected.

Results.

In total, 365 patients, with a median age of 59 years and a median World Health Organization performance status score of 1, were evaluated. The majority of patients (71%) were pretreated with systemic therapy, with a median of two lines. After specific study information had been given, 145 patients (40%) declined informed consent, 54% of them mainly because of low expectations regarding treatment benefits and concerns about potential side effects. Patients who had received previous systemic therapy consented more frequently than others. After initial consent, 61 patients (17%) still did not receive study treatment, mostly because of secondary withdrawal of consent or rapid clinical deterioration prior to first dosing.

Discussion.

After specific referral to our hospital for participation in early clinical trials, only 44% of all patients who were informed about a specific phase I trial eventually participated. Reasons for both participation and nonparticipation were diverse. Patient participation rates could be improved by forming an experienced and dedicated study team.

Implications for Practice:

Clinical drug development is the basis for the further evolution of the field of medical oncology. The early phases of drug development are especially important for testing new compounds, because in these phases, pharmacokinetic endpoints and pharmacodynamic endpoints (toxicity and efficacy) are studied for the first time in a clinical setting. It is, therefore, essential to encourage patients to participate in early clinical trials, despite the potentially limited benefits for themselves. This can only be done in an adequate way if those patients are understood correctly for their motives and other reasons why they do or do not want to participate. In our opinion, the current inclusion rate is disappointingly low, despite specific referral to those trials. Based on our study results, patient incentives are clarified, which could help to improve the inclusion rate in early clinical trials in the future.

Introduction

Cancer is the leading cause of death in all developed countries, and therefore the development and subsequent clinical testing of new and better anticancer agents remain important [1]. Clinical drug development requires participation of cancer patients in clinical trials, the magnitude of which is well known to be far from optimal. Phase I clinical studies are performed in patients with advanced disease for whom standard approaches have either failed or do not exist [2]. Therefore, these patients may have received earlier lines of palliative systemic therapy, or any other form of palliative therapy, but they could also be treatment naïve. The primary aim of phase I studies is to determine the safety profile of a new agent (or a new combination). Antitumor effects are analyzed as a secondary endpoint, but the expected therapeutic benefit for the participating patient is relatively limited [3–5].

As a consequence, recruiting patients for early-phase clinical trials is a challenge. Historically, the elderly and people with a lower socioeconomic status participate less in clinical trials [6–9]. There is some controversy about the participation rate of minorities [10]. In 1993, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration retracted their 1977 policy that prohibited the participation of females of childbearing potential in phase I and early phase II trials. However, women are still underrepresented in phase I clinical trials, although their participation rate has increased in the last decade [7].

The reasons for patients to give or deny informed consent to undergo experimental therapy are multifactorial. The facts that limited or no other treatment options exist and that life expectancy is uncertain render the phase I population a vulnerable group [11, 12]. In addition, early-phase clinical trial participation is quite demanding for patients [13]. Several studies have indicated that, despite the fact that patients are adequately informed that trial participation is unlikely to offer them clinical benefit, hope for remission or even a cure of the disease is an important incentive to participate in early clinical trials [14–16]. Usually, altruistic reasons do not play an important role [17]. The decision to give consent is also influenced by the attitude of physicians and patients' relatives in the informed consent process, the contents of informed consent forms, past involvement in anticancer treatments, and attitude towards living with cancer [18–22]. Reasons for denying informed consent have rarely been investigated [23], although perceived understanding may play a role [24, 25].

Whereas many have reported outcome data from phase I populations, recruitment and enrollment data from phase I trials have rarely been reported. Here, we report on an institutional assessment of patient motives and other variables influencing patient enrollment into phase I oncology trials.

Materials and Methods

Patients

For 25 months (October 2008 to November 2010), all patients visiting the Erasmus University Medical Center, Daniel den Hoed Cancer Center outpatient clinic of medical oncology who received information about a specific phase I trial were retrospectively included in this study. During the study period, 19 phase I trials were open for inclusion at our center (supplemental online Table 1). In the Netherlands, nine centers, equally distributed throughout the country (Fig. 1), offer early clinical trials in oncology. Two of them are exclusive cancer centers, including our center. The Dutch health care system is freely accessible for every patient, and all residents are mandatorily insured for health care costs. Therefore, economic reasons to participate in a trial are probably negligible.

Figure 1.

Actual living places of referred patients in The Netherlands and Belgium, based on postal codes. Patients were classified according to their informed consent status: patients who did not sign an informed consent form (red circles), patients who signed an informed consent form and participated (green circles), and patients who signed an informed consent form but never started therapy (yellow circles). Black squares represent the nine Dutch centers where oncology phase I trials are offered.

All patients enrolled were specifically referred for trial participation because no (standard) treatment options were deemed to be available (any longer) to them. Patients were seen by a medical oncologist or a fellow to discuss treatment options and potential trial participation. Both general and specific phase I trial information was provided verbally and in writing, the latter by means of an institutional review board (IRB)-approved informed consent form. Subsequently, at the next visit, they were seen by a clinician or nurse practitioner to discuss participation in a specific phase I trial. Consent or refusal of consent was discussed during this appointment, within a median of 9 days after the first visit. For patients ultimately participating in multiple phase I trials during the period of the study, only the first informed consent procedure was considered for the present analysis.

Phase I Trial Characteristics

All phase I trials involved were open to patients with diverse histological types of solid tumors. Several phase I trials investigated combinations of drugs, and some combined systemic therapy with hyperthermia and radiation (supplemental online Table 1). In seven trials, participating patients had to be hospitalized for more than two nights, whereas in one trial patients had to visit the hospital daily for 5 days per week for four consecutive weeks. Phase I trial screening investigations included a physical examination, (routine) laboratory tests, electrocardiograms and baseline radiological examinations (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] scans). Additional investigations performed during trial participation included pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and pharmacogenetic sampling, hair collection, tumor and/or skin biopsies, dynamic enhanced MRI, and serial ophthalmologic examinations. The effort of undergoing these investigations was scored by oncologists and a nurse practitioner on a three-level Likert scale as: 1, small effort; 2, moderate effort; 3, big effort (supplemental online Table 1) [26].

Data Collection

Variables were collected from electronic patient charts. This electronic system was specifically designed to describe the medical history of cancer patients. The collected variables were: referral source (other departments of our hospital—internal, other hospitals—external, own department of medical oncology—own cancer population), tumor classification using the International Classification of Diseases (10th revision) [27], date of primary diagnosis, number of prior systemic anticancer treatments, number of prior systemic experimental treatments, World Health Organization (WHO) performance status (PS) score at the start of the informed consent period and at the final consent decision, age, gender, marital status, distance from home to the hospital, written informed consent, and eligibility for a specific proposed phase I trial. The following variables for all phase I studies were analyzed: tumor type, number of pages on consent form, and complexity of the trial. Complexity during the first two courses of treatment was defined by the number of hospital visits and the duration of hospitalization. Also, the number of studied agents and the type of agent (an experimental compound or registered drug for other indications) were studied. In addition, the required numbers and types of invasive procedures were analyzed. Patient charts were meticulously scrutinized in order to interpret patients' motives for nonparticipation, and their motives were categorized into groups.

Statistical Analysis

Data were first compared between patients who did and those who did not give informed consent to participate in a phase I trial. The Pearson's χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate, was used to compare discrete data between the two groups, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test (Mann-Whitney U-test) was used for continuous data. Next, the same analyses were performed but restricted to patients who gave informed consent, and the data were then compared between patients who did and those who did not start treatment within a phase I trial.

Results

Patient Characteristics

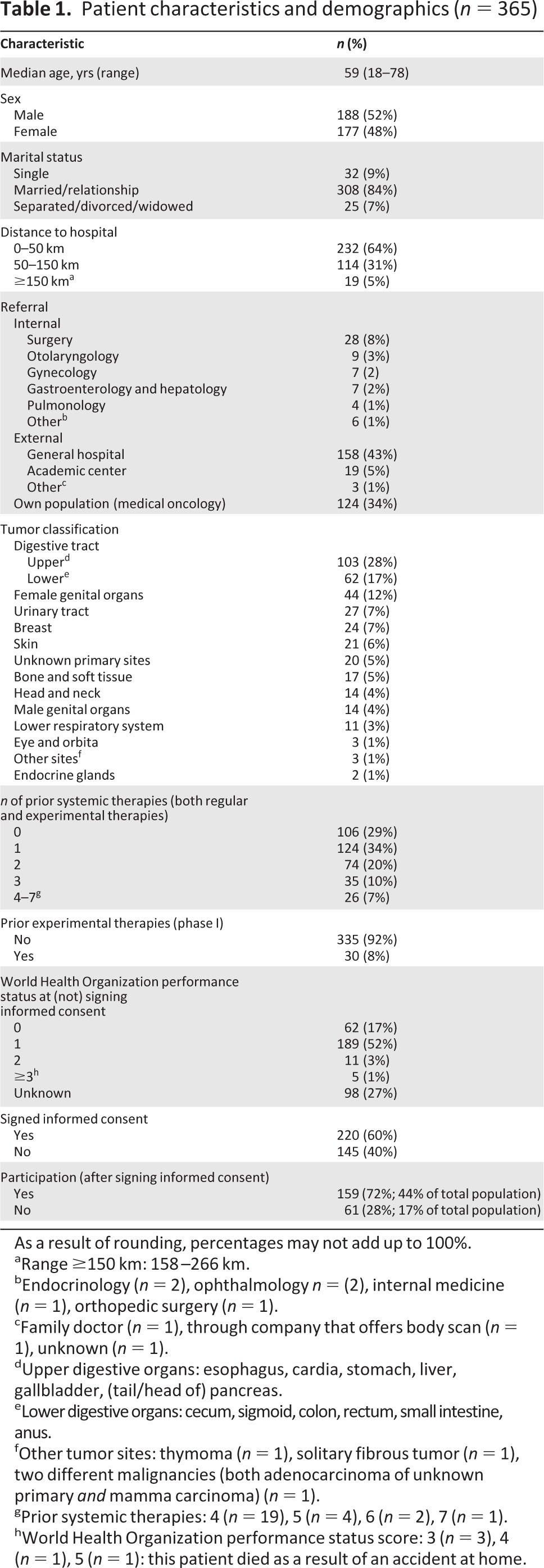

In total, 365 patients (188 men and 177 women) with a median age of 59 years (range, 18–78 years) were included (Table 1). External patients were referred by general hospitals from all over the country, but mostly from the Rotterdam (Southwest Netherlands) region (Fig. 1). The median distance between the patient's home and our cancer center was 31 km (range, 1–266 km). Most tumors originated from the gastrointestinal tract (45%). The majority of patients were pretreated with systemic therapy, with a median of two lines of treatment (range, 1–7). Patients without pretreatment were those with tumors for which no standard treatment options were considered to be available. The approach to include them in phase I trials is in line with the recommendations of the Dutch Society for Medical Oncology and is standard practice in The Netherlands. Only 8% of patients had previously participated in another phase I trial before October 2008. At the decisive moment of signing or not signing the informed consent form, most patients had a WHO PS score of 0 or 1. Despite being an inclusion criterion for most studies, PS was not yet formally scored for 98 patients. The vast majority of this specific group of patients (>90%) eventually ended up not participating, because of patient refusal in 63%.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and demographics (n = 365)

As a result of rounding, percentages may not add up to 100%.

aRange ≥150 km: 158–266 km.

bEndocrinology (n = 2), ophthalmology n = (2), internal medicine (n = 1), orthopedic surgery (n = 1).

cFamily doctor (n = 1), through company that offers body scan (n = 1), unknown (n = 1).

dUpper digestive organs: esophagus, cardia, stomach, liver, gallbladder, (tail/head of) pancreas.

eLower digestive organs: cecum, sigmoid, colon, rectum, small intestine, anus.

fOther tumor sites: thymoma (n = 1), solitary fibrous tumor (n = 1), two different malignancies (both adenocarcinoma of unknown primary and mamma carcinoma) (n = 1).

gPrior systemic therapies: 4 (n = 19), 5 (n = 4), 6 (n = 2), 7 (n = 1).

hWorld Health Organization performance status score: 3 (n = 3), 4 (n = 1), 5 (n = 1): this patient died as a result of an accident at home.

Recruitment and Participation

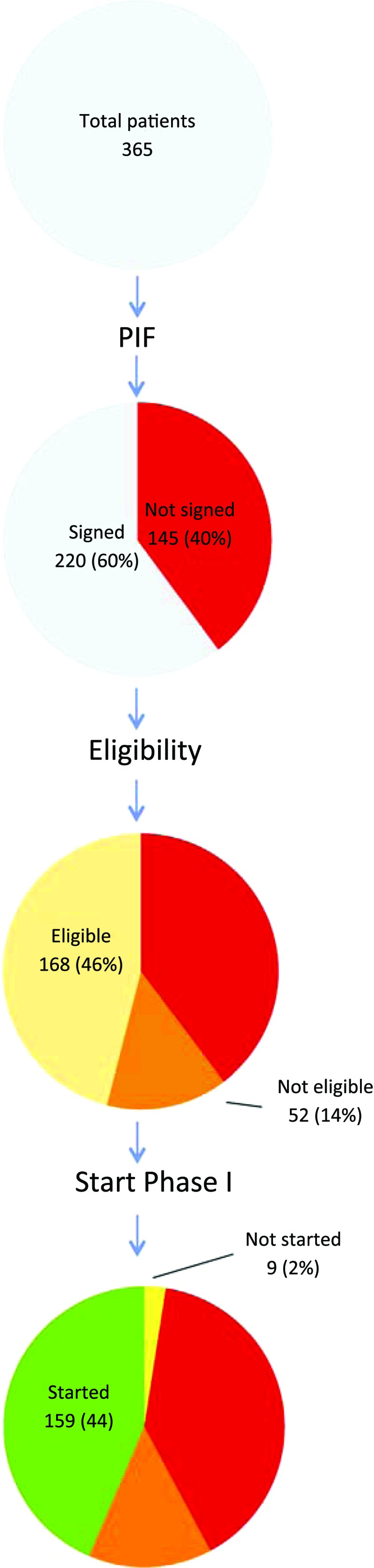

Figure 2 shows the consecutive steps of the process from the informed consent procedure until the actual start of the phase I study treatment. Despite their specific referral, 145 patients (40%) refused or were not eligible for study participation.

Figure 2.

Pie charts of patients receiving a patient information form (top pie, n = 365) and their decision to sign an informed consent form (second pie), their eligibility after signing (third pie), and their final ability to start in a specific phase I trial (bottom pie).

The most frequently mentioned reasons for not consenting to participate in a study were: (a) patient refusal (78 patients, 54%); (b) physiological reasons, mostly clinical deterioration and formal ineligibility according to protocol at the time of the informed consent visit (39 patients, 27%); and (c) being offered alternative palliative treatment options (most often radiotherapy, not in the context of a phase I trial; 27 patients, 19%). Patients refused study participation for various reasons, such as low expectations regarding treatment benefit, concern about side effects, and, after being given detailed information about a specific trial, not wishing to be exposed to an experimental agent. Both a declining clinical condition and a currently excellent condition were mentioned by individual patients as reasons not to participate.

Of the 220 (60%) patients who provided informed consent, 52 (14%) were found to be unable to start study participation. Rapid clinical deterioration occurred in 12 patients and 40 patients were found to be ineligible as a result of specific inclusion and exclusion criteria that were assessed after informed consent was given.

Finally, a small group of nine eligible patients (2%) did not commence study participation either because of late withdrawal of consent or the need for urgent palliative treatment modalities, such as radiation for pain control. As a consequence, only 44% of the initial population actually undertook phase I study participation.

Comparison of Variables

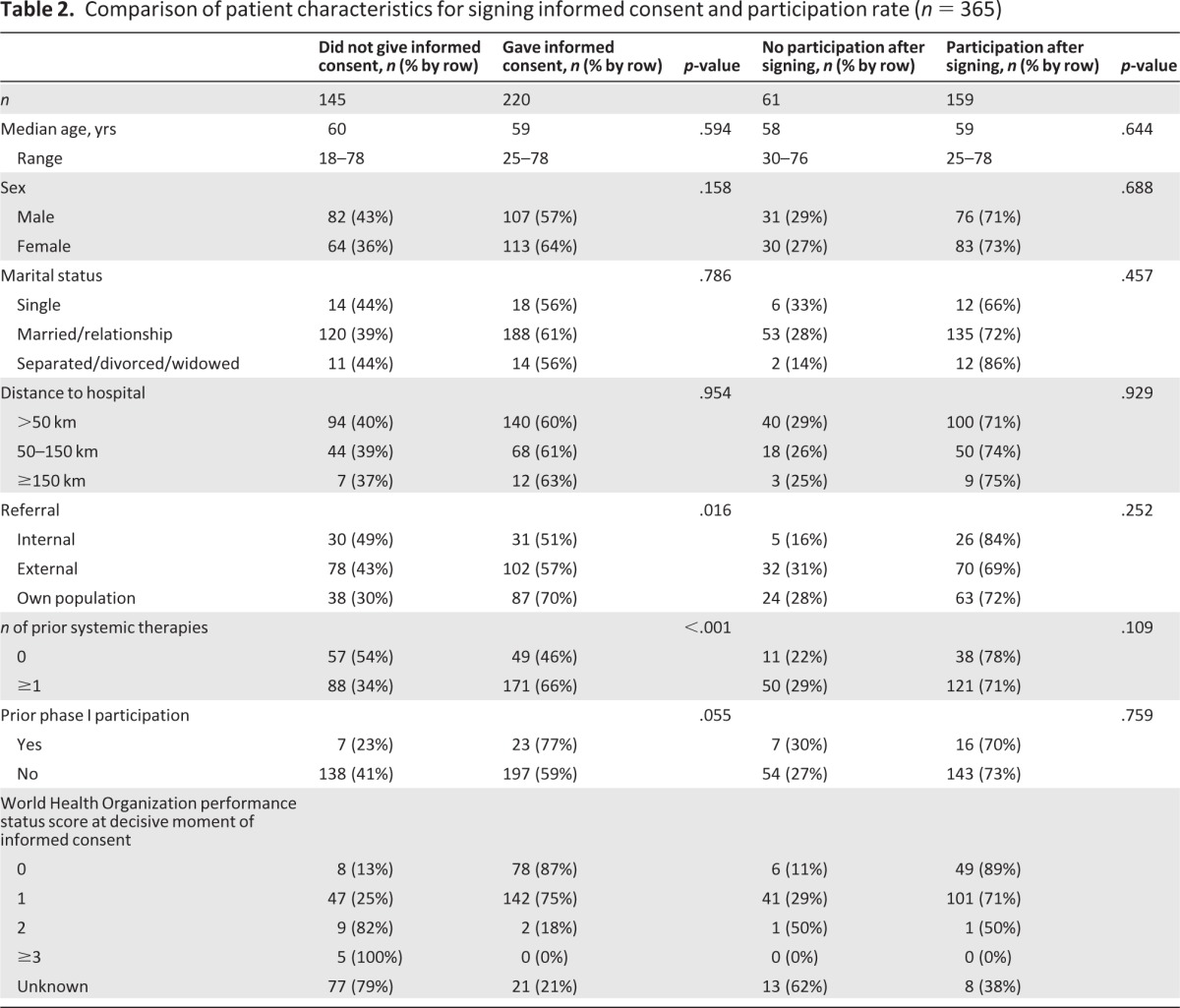

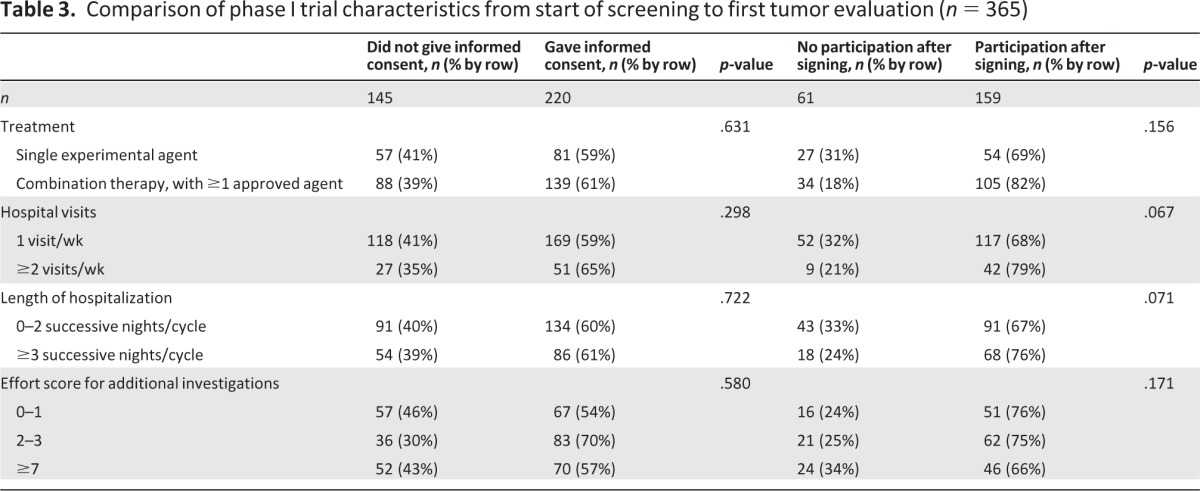

Sixty-six percent of patients who had received previous systemic therapy consented to participate, versus 46% of those who had not received systemic therapy before (p < .001). In addition, patients referred for phase I participation by external hospitals and by other internal departments provided informed consent less frequently than those who had already visited our medical oncology outpatient clinic (p = .016) (Table 2). The design of trials, that is, the number of agents, number of hospital visits per week, number of nights in the hospital per cycle, and burden of additional investigations, did not differ significantly between patients who did and those who did not give informed consent for study participation (Table 3). Moreover, age, marital status, sex, distance to the hospital (Fig. 1), and tumor type classification were not found to be decisive factors.

Table 2.

Comparison of patient characteristics for signing informed consent and participation rate (n = 365)

Table 3.

Comparison of phase I trial characteristics from start of screening to first tumor evaluation (n = 365)

Discussion

After specific referral for participation in phase I trials and provision of the IRB consent form of a specific phase I trial, more than half of the patients in this analysis ultimately did not consent to study participation or were found to be ineligible. Previous studies from the Royal Marsden Hospital in London, U.K. [28], and the Princess Margaret Hospital in Toronto, Canada [29], reported participation rates of 32% and 30%, respectively. However, in those studies, the population consisted of all patients referred for phase I treatment, whereas in our analysis only the group of patients receiving an IRB consent form were taken into account.

The reasons why patients denied consent were in line with the previous literature [23–25, 29]. A rapid decline in clinical condition as well as a stable and well-maintained clinical condition were reasons for patients to reject informed consent. From a patient perspective, no ideal moment for trial participation can be mentioned because individual motives influence the best moment in the course of their disease.

Because information and participation preferences can possibly change over time [30], patients who felt very well and did not consent because of that could potentially opt for study participation later on in the course of their disease. Several patients were disappointed with the quoted expected benefits or were concerned about potential side effects. Others were concerned that frequent hospital visits would interfere with their quality of life, which is of particular relevance given the limited life expectancy of these patients.

Only a small number of patients mentioned that a long travel distance to the hospital was a reason not to consent. This is encouraging because phase I trials are not, and never will be, available in every local hospital because of their academic nature. Interestingly, prior systemic treatment exposure was positively correlated with phase I study participation. Whether this can be explained by positive experiences with previous therapies, familiarity with the department, or other reasons remains largely unknown [19]. Patients' trust in the clinical study team may be an asset in the context of their willingness to participate. The fact that a higher percentage of the patient population previously treated at our own institute decided to participate in a study could support this hypothesis. Similar findings were also observed at the Princess Margaret Hospital, where patients who were referred from their own hospital consented to study participation more often [29]. However, the relationship with, or feeling of dependency toward, caregivers might also play a role here. An impression that research participation is strongly encouraged could be an additional factor. The potential relationship between familiarity with a certain department and other motives for participation are currently being prospectively assessed at our department using standardized questionnaires (Dutch Trial Registry number NTR3354).

In contrast to earlier data showing that females are underrepresented in phase I trials, the numbers of participating men and women were almost equal in our department. One of the possible explanations for this could be an increasing number of female cancer patients for whom no standard treatment options remain. Another explanation could be that patients are increasingly aware of data suggesting the potential benefit of phase I drugs in specific female cancers (i.e., ovarian, uterine, and cervical cancer) [31].

Quite a large number of patients did not meet one or more specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Clinical deterioration over time is a limiting barrier for both patients and investigators. The availability of an objective prognostic score that enables discrimination between patients with probable rapid deterioration and those with a true survival time >3 months—an inclusion criterion for most phase I studies—could prove to be a useful tool in the decision-making process of phase I study participation [32–34]. Still, a number of patients who gave informed consent and were willing to participate in a study eventually could not partake because they were found to have become ineligible during prestudy procedures that were performed after the informed consent form had been signed. We believe that this could have been disappointing for patients, but because of the many regulations accompanying and preceding clinical trial enrollment this, to a certain extent, may well be unavoidable. Nonetheless, in some cases, we feel that this kind of disappointment could have been prevented by better education among subinvestigators and by the use of a dedicated and experienced study team.

A limitation of our study is the fact that the results were obtained retrospectively. As a result, clinicians did not use standardized questionnaires to document reasons for participation or refusal thereof and the interpretation of some of the patients' motives may have influenced the results of this analysis. Another limitation of the current dataset is the absence of information about patients who could not participate in a phase I study because of a lack of available study slots. One of the barriers to finding new treatments against cancer [35, 36] is a shortage of available studies. Cooperation among medical centers in performing early clinical studies could increase the number of available studies. By further specialization and understanding the motivation of patients and the characteristics of these patients, these centers may also improve their aiding in the decision-making process.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Peter Barry (the Royal Marsden Hospital, London, United Kingdom) for assistance in proofreading and editing this manuscript.

This study was presented in part at the ECCO 16/ESMO 36/ESTRO 30 Annual Meeting, Stockholm, Sweden, September 23–27, 2011 (abstract #1256).

Gaia Schiavon is currently affiliated with the Breast Unit, Royal Marsden Hospital, London, U.K.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Ron H. Mathijssen, Diane A.J. van der Biessen, Bronno van der Holt, Ferry A.L.M. Eskens, Jaap Verweij

Provision of study material or patients: Ron H. Mathijssen, Diane A.J. van der Biessen, Merlijn A. Cranendonk, Gaia Schiavon, Jaap Verweij, Maja J.A. de Jonge

Collection and/or assembly of data: Diane A.J. van der Biessen, Merlijn A. Cranendonk, Gaia Schiavon, Jaap Verweij, Maja J.A. de Jonge

Data analysis and interpretation: Ron H. Mathijssen, Diane A.J. van der Biessen, Merlijn A. Cranendonk, Gaia Schiavon, Bronno van der Holt, Erik A.C. Wiemer, Ferry A.L.M. Eskens, Jaap Verweij, Maja J.A. de Jonge

Manuscript writing: Ron H. Mathijssen, Diane A.J. van der Biessen, Merlijn A. Cranendonk, Gaia Schiavon, Bronno van der Holt, Erik A.C. Wiemer, Ferry A.L.M. Eskens, Jaap Verweij, Maja J.A. de Jonge

Final approval of manuscript: Ron H. Mathijssen, Diane A.J. van der Biessen, Merlijn A. Cranendonk, Gaia Schiavon, Bronno van der Holt, Erik A.C. Wiemer, Ferry A.L.M. Eskens, Jaap Verweij, Maja J.A. de Jonge

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Cancer Fact Sheet No 297. [Accessed November 23, 2012]. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/index.html.

- 2.Meropol NJ, Weinfurt KP, Burnett CB, et al. Perceptions of patients and physicians regarding phase I cancer clinical trials: Implications for physician-patient communication. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2589–2596. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller FG, Joffe S. Benefit in phase 1 oncology trials: Therapeutic misconception or reasonable treatment option? Clin Trials. 2008;5:617–623. doi: 10.1177/1740774508097576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulmasy DP, Astrow AB, He MK, et al. The culture of faith and hope: Patients' justifications for their high estimations of expected therapeutic benefit when enrolling in early phase oncology trials. Cancer. 2010;116:3702–3711. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts TG, Jr, Goulart BH, Squitieri L, et al. Trends in the risks and benefits to patients with cancer participating in phase 1 clinical trials. JAMA. 2004;292:2130–2140. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.17.2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Townsley CA, Chan KK, Pond GR, et al. Understanding the attitudes of the elderly towards enrolment into cancer clinical trials. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinnow E, Sharma P, Parekh A, et al. Increasing participation of women in early phase clinical trials approved by the FDA. Womens Health Issues. 2009;19:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Rayes BF, Jasti P, Severson RK, et al. Impact of race, age, and socioeconomic status on participation in pancreatic cancer clinical trials. Pancreas. 2010;39:967–971. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181da91dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zafar SF, Heilbrun LK, Vishnu P, et al. Participation and survival of geriatric patients in phase I clinical trials: The Karmanos Cancer Institute (KCI) experience. J Geriatr Oncol. 2011;2:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher JA, Kalbaugh CA. Challenging assumptions about minority participation in US clinical research. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:2217–2222. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinfurt KP, Castel LD, Li Y, et al. The correlation between patient characteristics and expectations of benefit from phase I clinical trials. Cancer. 2003;98:166–175. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catt S, Langridge C, Fallowfield L, et al. Reasons given by patients for participating, or not, in phase 1 cancer trials. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1490–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craft BS, Kurzrock R, Lei X, et al. The changing face of phase 1 cancer clinical trials: New challenges in study requirements. Cancer. 2009;115:1592–1597. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daugherty C, Ratain MJ, Grochowski E, et al. Perceptions of cancer patients and their physicians involved in phase I trials. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1062–1072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.5.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoh K, Sasaki Y, Fujii H, et al. Patients in phase I trials of anti-cancer agents in Japan: Motivation, comprehension and expectations. Br J Cancer. 1997;76:107–113. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nurgat ZA, Craig W, Campbell NC, et al. Patient motivations surrounding participation in phase I and phase II clinical trial of cancer chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1001–1005. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Truong TH, Weeks JC, Cook EF, et al. Altruism among participants in cancer clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2011;8:616–623. doi: 10.1177/1740774511414444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchison C. Phase I trials in cancer patients: Participants' perceptions. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 1998;7:15–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.1998.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohara I, Inoue T. Searching for a way to live to the end: Decision-making process in patients considering participation in cancer phase I clinical trials. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:E124–E132. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.E124-E132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung WY, Pond GR, Heslegrave RJ, et al. The contents and readability of informed consent forms for oncology clinical trials. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:387–392. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181b20641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wootten AC, Abbott JM, Siddons HM, et al. A qualitative assessment of the experience of participating in a cancer-related clinical trial. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:49–55. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0787-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Zhang H, Yu C, et al. The attitudes of oncology physicians and nurses toward phase I, II, and III cancer clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32:649–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox K, McGarry J. Why patients don't take part in cancer clinical trials: An overview of the literature. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2003;12:114–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2003.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergenmar M, Johansson H, Wilking N. Levels of knowledge and perceived understanding among participants in cancer clinical trials—Factors related to the informed consent procedure. Clin Trials. 2011;8:77–84. doi: 10.1177/1740774510384516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergenmar M, Molin C, Wilking N, et al. Knowledge and understanding among cancer patients consenting to participate in clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2627–2633. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards AL, Kenney KC. A comparison of the Thurstone and Likert techniques of attitude scale construction. J Appl Psychol. 1946;30:72–83. doi: 10.1037/h0062418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Manual of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision. Volume 2. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karavasilis V, Digue L, Arkenau T, et al. Identification of factors limiting patient recruitment into phase I trials: A study from the Royal Marsden Hospital. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:978–982. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho J, Pond GR, Newman C, et al. Barriers in phase I cancer clinical trials referrals and enrollment: Five-year experience at the Princess Margaret Hospital. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pardon K, Deschepper R, Vander Stichele R, et al. Changing preferences for information and participation in the last phase of life: A longitudinal study among newly diagnosed advanced lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2473–2482. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moroney J, Wheler J, Hong D, et al. Phase I clinical trials in 85 patients with gynecologic cancer: The M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117:467–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chau NG, Florescu A, Chan KK, et al. Early mortality and overall survival in oncology phase I trial participants: Can we improve patient selection? BMC Cancer. 2011;11:426. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olmos D, A'hern RP, Marsoni S, et al. Patient selection for oncology phase I trials: A multi-institutional study of prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:996–1004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.5074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arkenau HT, Olmos D, Ang JE, et al. 90-Days mortality rate in patients treated within the context of a phase-I trial: How should we identify patients who should not go on trial? Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1536–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lara PN, Jr., Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: Identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1728–1733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castel P, Négrier S, Boissel JP. Why don't cancer patients enter clinical trials? A review. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:1744–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]