Abstract

Introduction

There has been limited investigation of the sexuality and sexual dysfunction in non-heterosexual subjects by the sexual medicine community. Additional research in these populations is needed.

Aims

To investigate and compare sexuality and sexual function in students of varying sexual orientations.

Methods

An internet-based survey on sexuality was administered to medical students in North American between the months of February and July of 2008.

Main Outcome Measures

All subjects provided information on their ethnodemographic characteristics, sexual orientation, and sexual history. Subjects also completed a series of widely-utilized instruments for the assessment of human sexuality (International Index of Erectile Function [IIEF], Female Sexual Function Index [FSFI], Premature Ejaculation Diagnostic Tool [PEDT], Index of Sex Life [ISL]).

Results

There were 2,276 completed responses to the question on sexual orientation. 13.2% of male respondents and 4.7% of female respondents reported a homosexual orientation; 2.5% of male and 5.7% of female respondents reported a bisexual orientation. Many heterosexual males and females reported same-sex sexual experiences (4% and 10%, respectively). Opposite-sex experiences were very common in the male and female homosexual population (37% and 44%, respectively). The prevalence of premature ejaculation (PEDT > 8) was similar among heterosexual and homosexual men (16% and 17%, P = 0.7, respectively). Erectile dysfunction (IIEF-EF < 26) was more common in homosexual men relative to heterosexual men (24% vs. 12%, P = 0.02). High risk for female sexual dysfunction (FSFI < 26.55) was more common in heterosexual and bisexual women compared with lesbians (51%, 45%, and 29%, respectively, P = 0.005).

Conclusion

In this survey of highly educated young professionals, numerous similarities and some important differences in sexuality and sexual function were noted based on sexual orientation. It is unclear whether the dissimilarities represent differing relative prevalence of sexual problems or discrepancies in patterns of sex behavior and interpretation of the survey questions.

Keywords: Homosexual, Bisexual, Medical Student, Female Sexual Function, Male Sexual Function, Heterosexual

Introduction

Homosexual men and women have received limited attention in the sexual medicine literature despite constituting a substantial minority of the population (estimated at 4–5% and 2–3% for male and female, respectively) [1–3]. Nonheterosexual orientation is an exclusion criterion in many large scale studies in sexual medicine [4,5]. Although the exclusion of homosexuals from these studies is grounded in the need for a homogenous study population for optimization of scientific rigor rather than prejudice, the end result is that homosexual people are often excluded from important clinical trials [4,5]. Furthermore, the majority of instruments for the assessment of sexual problems have not been validated in homosexual patients and feature language oriented towards heterosexual people [6,7].

Much of the biomedical literature on these sexual minority groups is centered on high-risk sexual behaviors and sexual dysfunction in HIV-positive men [8,9]. However, recent normative sexual dysfunction research in homosexual subjects has provided interesting preliminary data. An internet-based survey of 7001 men who have sex with men found that 79% of men reported one or more sexual dysfunction symptoms [10]. The most common problems were low sexual desire, erection problems, and performance anxiety [10]. In addition, a report on Chinese men who have sex with men also found a relatively high incidence (around 43%) of sexual concerns. In this population, there was an association between social support/acceptance of sexual orientation from associates and sexual dysfunction, HIV-risk-related behaviors, and sociocultural factors [11]. Bancroft and colleagues analyzed a large convenience sample of gay men (N = 1,196) and age-matched heterosexual men (N = 1,558) for erectile dysfunction and ejaculatory problems. Problems with erection over the past 3 months were reported by 43% of gay men compared with 31% of heterosexual men; a problem with erectile function at some point in life was reported by 58% of gay men and 46% of heterosexual men. These differences were statistically significant, leading the authors to speculate that either erectile dysfunction is more common in homosexual men and/or that erectile function plays a more critical role in the sexual lives of gay men [12].

It is implied that sexual dysfunction may impact sexual minority groups in ways that are different from what is observed in heterosexuals. Our research team recently surveyed sexuality and sexual practices of medical students enrolled in osteopathic and allopathic medical schools in North America. We subsequently conducted a cross-sectional subset analysis stratifying sexual practice and dysfunction by sexual orientation. We hypothesized that heterosexual, homosexual and bisexual medical students would have differing sexual repertoires and experiences and that the rate of sexual problems might differ significantly between individuals of different sexual orientations.

Methods

Study Population

Medical students in North America were invited to participate in a cross-sectional internet-based survey of sexual practices and dysfunction. Invitations were extended via postings on the American Medical Student Association list-serves, the Student-Doctor Network, and a news story posted on Medscape.com. The survey was administered through QuestionPro.com (Survey Analytics LLC, Seattle, WA, USA) and was available from February 22, 2008 to July 31, 2008. Approval for this study and the survey instrument was given by our Institutional Committee for Human Research. Implied consent was assumed by subject participation in, and completion of, the survey instrument.

Exposure Variables

Primary Outcome Variable

Students were asked “What is your sexual orientation?” and given the option of selecting “heterosexual”, “homosexual”, “bisexual”, “asexual”, or “other”. We defined heterosexuality and homosexuality as attraction to members of the opposite or same gender, respectively. We defined bisexuality as attraction to both genders with no or only slight preference for one gender over the other. Asexuality was defined as lack of attraction to members of either gender.

Socio-Demographic

The survey gathered demographic characteristics such as age (continuous), gender (male/female/other) sexual relationship status (yes/no), and prior maternity/paternity (yes/no).

Sexual Experience

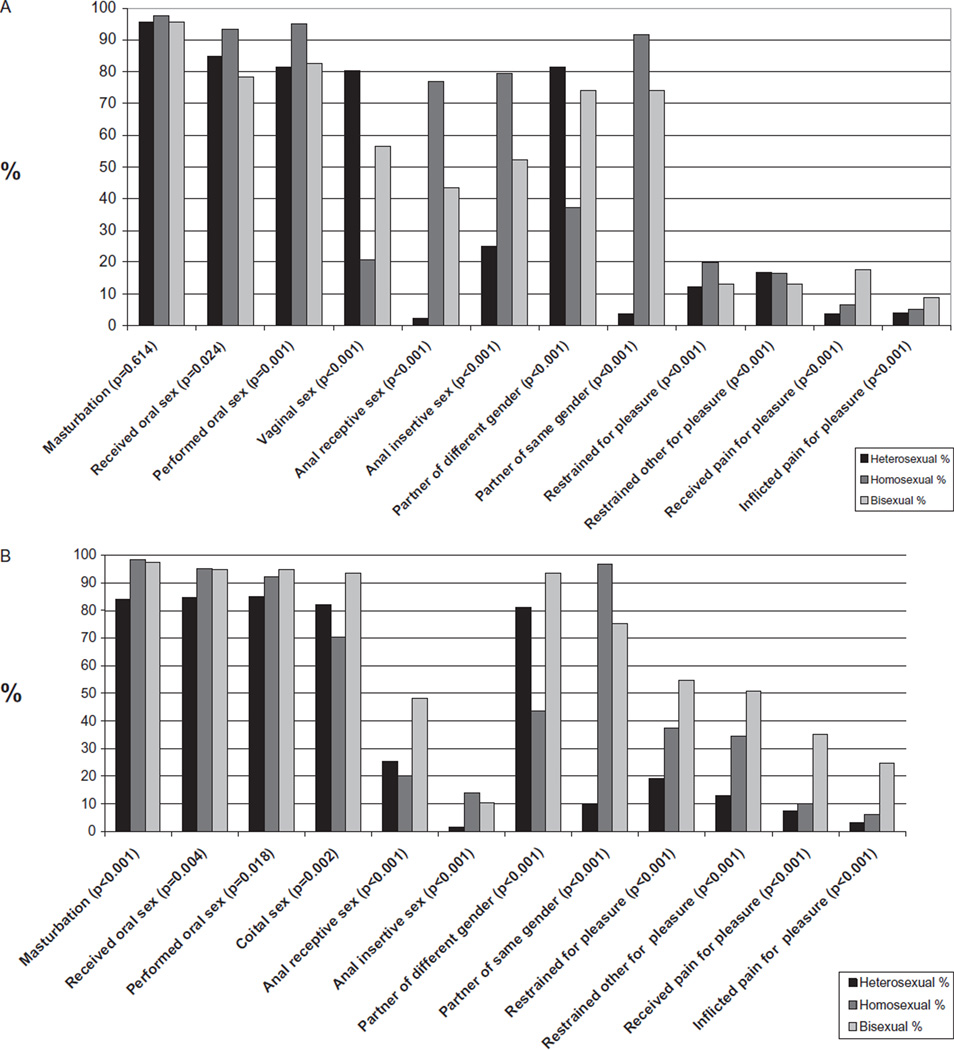

Subjects were asked their age at first intercourse as defined by the individual (continuous), number of lifetime and recent partners (categorical), and whether or not the subject had engaged in several specific sexual acts (listed in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sexual practices among male and female North American medical students. Percentages of students who have engaged in various sexual activities (A) male subjects (B) female subjects.

Sexual Quality of Life Instruments

Gender specific sexual function instruments were utilized to screen for sexual problems. Male subjects completed the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), a 15-item instrument assessing male sexual function (desire, erectile function, intercourse satisfaction, orgasmic function, and overall satisfaction) [6]. The erectile function domain (IIEF-EF) consists of 6 questions (score range 5–30); cut-off scores were used to classify ED (≥26 = no ED, 22–25 = mild ED, 17–21 = mild–moderate ED, 11–16 = moderate ED, ≤10 = severe ED) [13]. Premature ejaculation was evaluated with the Premature Ejaculation Diagnostic Tool (PEDT) [14,15]. Subjects with PEDT scores less than 9 were considered normal. PEDT scores of 9 or 10 represent “high risk for PE” whereas scores above 11 represent clinically significant PE. Male subjects who were in relationships completed the Self-Esteem and Relationship quality instrument (SEAR). SEAR measures two domains of relationship quality; sexual relationship and confidence (which are further divided into self-esteem and relationship quality subdomains) [16].

Female subjects completed the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), a 19 item questionnaire with domains quantifying desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain [17]. A total score of 26.55 or less on the FSFI (score range 2–36) was utilized as a cut-off value for “high risk” of female sexual dysfunction (FSD) [18]. Only those women who completed all questions were included in the calculation of total FSFI score. Female subjects in a relationship completed the Index of Sex Life (ISL) to assess their relationship quality and sexual desire [19].

The IIEF, PEDT, and FSFI were designed and initially validated for subjects participating in heterosexual coitus; therefore, IIEF, PEDT, and FSFI scores from subjects who did not report prior intercourse were excluded from subsequent analysis. The FSFI has been validated for use in lesbian subjects and recently the IIEF was validated for use in HIV-positive men who have sex with men [7,20]. The modified IIEF was not available at the time of study inception; furthermore, our objective was to obtain data using single instruments in a diverse population; hence, we did not create separate questionnaires for homosexual and heterosexual subjects. In order to make the instruments inclusive of nonheterosexual subjects, minor modifications to syntax were made. Gender specific terms for the subject’s partner were replaced with gender neutral pronouns. “Sexual intercourse” was expanded to include “vaginal intercourse and/or stimulation of the genitalia with hands or mouth in the intent of producing orgasm (not as part of foreplay)” for the FSFI and “entering your partner’s mouth, vagina, or anus” for the IIEF and PEDT. Subjects with a gender identity other than male or female were asked to select the instruments most applicable to their unique cases.

In addition to the quantitative instruments, subjects answered a single item subjective assessment question regarding their sexual function at present. Response options included: (i) “I am satisfied with my sexual function and would not change anything”; (ii) “I am mostly satisfied with my sexual function but there are things I would like to change”; (iii) “I am dissatisfied with my sexual function but I don’t want to change anything at this time”; (iv) “I am dissatisfied with my sexual function and there are things I would like to change”; (v) “I have a sexual problem or dysfunction and would like to do something about it”; and (vi) “Sexual function and dysfunction are not issues for me”.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. Chi-squared tests were used for categorical variables, whereas analysis of variance was used to assess differences for continuous variables. We report odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals to model the association between subject sexual characteristics, orientation, and sexual dysfunction. Multivariate logistic regression models were developed with a priori selected predictor variables. Subjects with missing data were excluded from multivariate analysis. Statistical significance was defined as a P < 0.05 and all tests were two-sided. STATA 11 (Statacorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all analysis.

Results

There were 2,276 subjects who completed the survey’s sexual orientation question; of these, 919 were men and 1,357 were women. Eight subjects reported a gender other than male/female; because of small numbers these subjects were not included in subsequent analyses.

Demographic data are summarized in Table 1. Homosexual or bisexual orientation was reported by 121 (13.2%) and 23 (2.5%) of the male subjects, respectively. Homosexual or bisexual orientation was reported by 64 (4.7%) and 77 (5.7%) of the female subjects, respectively. There were no significant differences between heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual subjects with respect to ethnicity, geographic location, or medical school year (data not shown).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of male and female medical students stratified by sexual orientation

| Female | Male | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age | ||||

| Heterosexual | 25.3 | 3.3 | 25.8 | 4.2 |

| Homosexual | 26.1 | 3.4 | 24.1 | 2.8 |

| Bisexual | 26.5 | 4.3 | 25.5 | 3.5 |

| N | % | N | % | |

| Sexual preference | ||||

| Heterosexual | 1,210 | 89.2 | 772 | 84 |

| Homosexual | 64 | 4.7 | 121 | 13.2 |

| Bisexual | 77 | 5.7 | 23 | 2.5 |

| Total | 1,357 | 100 | 919 | 100 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 913 | 69.5 | 623 | 70.1 |

| Hispanic | 82 | 6.3 | 63 | 7.1 |

| Black | 55 | 4.2 | 23 | 2.6 |

| Asian | 165 | 12.5 | 131 | 14.7 |

| Other | 98 | 7.5 | 49 | 5.5 |

| Prior paternity/maternity | ||||

| Heterosexual | 65 | 5.4 | 71 | 9.3 |

| Homosexual | 2 | 3.1 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Bisexual | 6 | 7.8 | 0 | 0 |

| Married/domestic partnership | ||||

| Heterosexual | 374 | 45.2 | 243 | 48.1 |

| Homosexual | 19 | 46.3 | 17 | 32.7 |

| Bisexual | 29 | 60.4 | 3 | 23.1 |

SD = standard deviation.

Male respondent sexual practice, stratified by sexual orientation, is presented in Figure 1A. Receptive and insertive oral and anal intercourse was more common in homosexual men relative to heterosexual and bisexual men, whereas vaginal intercourse was more common in heterosexual men relative to homosexual and bisexual men. Homosexual and bisexual men were less likely to be in a current sexual relationship or domestic partnership or to have children (Tables 1 and 2). Heterosexual men tended to have had fewer partners (over the past 6 months and over their lifetime) compared with both bisexual and homosexual men.

Table 2.

Sexual practices and function among heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual male medical students

| Heterosexual | Homosexual | Bisexual | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P value | |

| Age of first intercourse | 18.8 | 2.7 | 18.6 | 2.7 | 18.3 | 2.4 | 0.59 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Virgin (no intercourse) | 113 | 14.6 | 11 | 9.1 | 6 | 26.1 | 0.07 |

| Current sexual relationship | 518 | 67.1 | 55 | 45.5 | 13 | 56.5 | <0.001 |

| # Sex partners (last 6 months) | |||||||

| 0 | 50 | 7.6 | 9 | 8.2 | 2 | 11.8 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 473 | 72.0 | 48 | 43.6 | 7 | 41.2 | |

| 2+ | 134 | 20.4 | 53 | 48.3 | 8 | 47.1 | |

| # Sex partners (lifetime) | |||||||

| 1 | 154 | 23.6 | 4 | 3.8 | 1 | 5.9 | <0.001 |

| 2–5 | 238 | 36.4 | 25 | 23.9 | 6 | 35.3 | |

| 6–10 | 129 | 19.7 | 25 | 23.6 | 5 | 29.4 | |

| 11+ | 133 | 20.3 | 52 | 49.1 | 5 | 29.4 | |

| Erectile dysfunction | |||||||

| IIEF-EF >26 | 551 | 87.6 | 71 | 75.5 | 11 | 78.6 | 0.02 |

| IIEF-EF 22–25 | 51 | 8.1 | 14 | 14.9 | 3 | 21.4 | |

| IIEF-EF 17–21 | 22 | 3.5 | 6 | 6.4 | 0 | 0 | |

| IIEF-EF 11–16 | 4 | 0.6 | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | |

| IIEF-EF 6–10 | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 2.1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Premature ejaculation (PE) | |||||||

| PE | 71 | 16.2 | 13 | 17.3 | 3 | 33 | 0.68 |

| No PE | 334 | 76.0 | 57 | 76.0 | 5 | 55.6 | |

| High-risk of PE | 33 | 7.5 | 5 | 6.7 | 1 | 11.0 | |

| How do you feel about your sexual function at this time? | |||||||

| Sexual function is not an issue for me | 36 | 4.8 | 5 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.05 |

| Satisfied, desire no change | 226 | 30.4 | 27 | 22.7 | 3 | 13.6 | |

| Mostly satisfied, desire change | 375 | 50.4 | 60 | 50.4 | 16 | 72.7 | |

| Dissatisfied, desire no change | 13 | 1.8 | 2 | 1.7 | 1 | 4.6 | |

| Dissatisfied, desire change | 74 | 10 | 19 | 16 | 0 | 0 | |

| I feel I have a sex dysfunction, and desire change | 20 | 2.7 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 9.1 | |

| SEAR | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Sex relationship | 83 | 13.3 | 81 | 13.8 | 77.7 | 14.2 | 0.23 |

| Confidence | 87.8 | 12.9 | 84.7 | 12.8 | 79.5 | 15 | 0.02 |

| Self-esteem | 88.3 | 14.4 | 85 | 15.7 | 75.8 | 18 | 0.003 |

| Relationship | 87 | 14.8 | 84 | 15.3 | 86.9 | 13.2 | 0.36 |

| Total | 85 | 12.2 | 82.6 | 12.6 | 78.5 | 13.8 | 0.08 |

SD = standard deviation; IIEF-EF = International Index of Erectile Function-erectile function domain; SEAR = Self-Esteem and Relationship quality instrument.

Male sexual function results, stratified by sexual orientation, are listed in Table 2. Erectile dysfunction of all severity levels was more common in homosexual men (P = 0.019). There were no significant differences between groups with respect to the presence of PE or high risk of PE. Heterosexual men where more likely to report a higher SEAR-confidence score (P = 0.021) relative to bisexual men; this difference was driven primarily by higher SEAR-self-esteem scores in heterosexual men (P = 0.003). Heterosexual men were also more likely than either homosexual or bisexual men to report general satisfaction with sexual function based on the single item question (P = 0.05).

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for erectile dysfunction is shown in Table 3. In an unadjusted logistic model, homosexual orientation was associated with greater odds of ED (OR 2.29, 95% CI 1.35–3.87, P = 0.002). However, after adjusting for the number of partners in the last 6 months, marriage status, age of losing virginity, age, and SEAR scores, the association was no longer strictly significant (OR 2.27 95% CI 0.89–5.75, P = 0.083). In the adjusted model, being married or in a domestic partnership, losing one’s virginity at a younger age, and higher SEAR scores were associated with lower odds of ED.

Table 3.

Adjusted and unadjusted multivariate logistic regression analysis of sexual characteristics in North American medical students with erectile dysfunction (IIEF < 26)

| Odds ratio |

P value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Unadjusted | |||

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | Ref | ||

| Homosexual | 2.29 | 0.002 | 1.35–3.87 |

| Bisexual | 1.93 | 0.32 | 0.53–7.06 |

| B. Adjusted | |||

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | Ref | ||

| Homosexual | 2.27 | 0.083 | 0.89–5.75 |

| Bisexual | 0.66 | 0.657 | 0.10–4.2 |

| Sexual partners in the past 6 months | |||

| 0 | ref | ||

| 1 | 0.48 | 0.545 | 0.05–5.14 |

| 2 to 5 | 0.91 | 0.937 | 0.08–10.3 |

| 6 plus | 4.77 | 0.367 | 0.16–142.8 |

| Married/domestic partnership | 0.19 | <0.001 | 0.08–0.45 |

| Age virginity lost | 0.88 | 0.042 | 0.77–0.99 |

| Age | 1.16 | 0.478 | 0.77–1.72 |

| SEAR total | 1.16 | 0.109 | 0.97–1.40 |

| SEAR sexual relationship | 0.85 | 0.01 | 0.74–0.96 |

| SEAR esteem | 0.92 | 0.017 | 0.87–0.99 |

SEAR = Self-Esteem and Relationship quality instrument; CI = confidence interval.

Female respondent sexual practice, stratified by sexual orientation, is presented in Figure 1B. Homosexual and bisexual women were more likely to have masturbated and to have both performed and received oral sex relative to heterosexual women although the majority of all women had performed all three of these activities. Lesbian women were less likely to have engaged in vaginal intercourse relative to other groups although 70% of the lesbians in this sample had done so; this number is similar to what has been previously reported in lesbian women [21]. Both bisexual and homosexual women tended to have had more partners (over both the lifetime and within the past 6 months), were less likely to be virgins (Table 4), and had a more diverse sexual repertoire relative to heterosexual women (Figure 1). No significant differences were noted in relationship status between groups.

Table 4.

Sexual practices and function among heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual female medical students

| Heterosexual | Homosexual | Bisexual | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P value | |

| Age of first intercourse | 18.7 | 2.7 | 18.4 | 2.4 | 17.7 | 2.2 | 0.053 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Virgin (no intercourse) | 163 | 13.5 | 2 | 3.1 | 3 | 3.9 | 0.003 |

| Current sexual relationship | 850 | 70.3 | 42 | 65.6 | 51 | 66.2 | 0.574 |

| # Sex partners (last 6 months) | |||||||

| 0 | 91 | 8.7 | 4 | 6.5 | 4 | 5.4 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 812 | 77.9 | 43.0 | 69.4 | 45.0 | 60.8 | |

| 2+ | 139 | 13.4 | 15 | 24.2 | 25 | 33.8 | |

| # Sex partners (lifetime) | |||||||

| 1 | 244 | 23.6 | 5 | 8.1 | 4 | 5.5 | <0.001 |

| 2–5 | 422 | 40.7 | 23 | 37.1 | 19 | 26 | |

| 6–10 | 211 | 20.4 | 15 | 24.2 | 22 | 30.1 | |

| 11+ | 159 | 15.4 | 19 | 30.6 | 28 | 38.4 | |

| FSFI | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Desire | 3.7 | 1.2 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 4.0 | 1.2 | 0.037 |

| Arousal | 3.8 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 1.9 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 0.062 |

| Lubrication | 4.2 | 2.1 | 4.6 | 2.1 | 4.5 | 1.8 | 0.146 |

| Orgasm | 3.5 | 2.1 | 4.5 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 1.9 | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction | 4.0 | 1.6 | 4.2 | 1.5 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 0.707 |

| Pain | 4.0 | 2.3 | 4.6 | 2.1 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 0.015 |

| Total | 24.0 | 8.7 | 26.2 | 9.42 | 25.4 | 7.6 | 0.088 |

| How do you feel about your sexual function at this time? | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Sexuality is not an issue for me | 68 | 6 | 3 | 4.8 | 1 | 1.4 | 0.825 |

| Satisfied, desire no change | 221 | 19.6 | 16 | 25.8 | 15 | 20.3 | |

| Mostly satisfied, desire change | 530 | 46.9 | 27 | 43.6 | 34 | 46 | |

| Dissatisfied, desire no change | 35 | 3.1 | 2 | 3.2 | 3 | 4.1 | |

| Dissatisfied, desire change | 217 | 19.2 | 10 | 16.1 | 15 | 20.3 | |

| I feel I have a sex dysfunction and desire change | 58 | 5.1 | 4 | 6.5 | 6 | 8.1 | |

| ISL | |||||||

| Sex life satisfaction | 21.8 | 5.2 | 21.7 | 5.2 | 21.8 | 5.5 | 0.995 |

| Sex drive | 6.1 | 2.8 | 5.1 | 2.6 | 6.5 | 2.6 | 0.067 |

| General life satisfaction | 7.9 | 1.7 | 7.7 | 1.3 | 7.4 | 2 | 0.095 |

| Interference from disease | 46 | 5.4 | 4 | 9.5 | 7 | 13.7 | 0.033 |

| Interference from gyne problem | 121 | 14.2 | 6 | 14.3 | 13 | 25.5 | 0.089 |

| Lack of partner availability | 256 | 30.1 | 17 | 40.5 | 13 | 25.5 | 0.269 |

FSFI = Female Sexual Function Index; ISL = Index of Sex Life; SD = standard deviation.

Results from the ISL and FSFI are listed in Table 4. There were also slight but statistically significant differences in mean FSFI domain score between groups; specifically, homosexual and bisexual women had higher mean desire, orgasm, and pain scores (P < 0.05). The number of women with FSFI scores <26.55 was 519 (26.2%), 16 (8.5%), and 31 (30.1%) for heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual women. Despite these differences, neither mean FSFI-satisfaction nor ISL-sex life satisfaction differed significantly between groups (P = 0.707 and P = 0.869, respectively). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in subjective report of feelings about sexual function based on sexual orientation (P = 0.825). Lesbian and bisexual women were significantly more likely to report interference in their sexual lives from disease relative to heterosexual women (0.033); there were no other significant differences between groups with respect to specific factors that interfered with sexual life. Interestingly, although lesbian women scored higher on the FSFI desire domain relative to heterosexual women, mean scores for ISL-sex drive (a proxy measure for women in relationships) tended to be lower in lesbians (P = 0.067).

In the unadjusted logistic regression model, homosexual women were less likely to be at high risk of FSD relative to heterosexual women (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.22–0.71, P = 0.002) (Table 5). After adjusting for the number of partners in the last 6 months, marriage status, age of losing virginity, and chronologic age, homosexual orientation remained associated with lower odds of FSD (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.06–0.72, P = 0.013). Higher total ISL score was associated with higher FSFI scores.

Table 5.

Adjusted and unadjusted multivariate logistic regression analysis of characteristics associated with a high risk of female sexual dysfunction (FSFI <26.55) in North American medical students

| Odds ratio | P value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Unadjusted | |||

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | Ref | ||

| Homosexual | 0.39 | 0.002 | 0.22–0.71 |

| Bisexual | 0.8 | 0.368 | 0.49–1.3 |

| B. Adjusted | |||

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | Ref | ||

| Homosexual | 0.21 | 0.013 | 0.06–0.72 |

| Bisexual | 0.6 | 0.304 | 0.22–1.6 |

| Sex partners last 6 months | |||

| 0 | Ref | ||

| 1 | 1.09 | 0.948 | 0.09–12.6 |

| 2 to 5 | 0.53 | 0.624 | 0.04–6.78 |

| Married | 1.26 | 0.319 | 0.8–2.0 |

| Age virginity lost | 1.07 | 0.131 | 0.98–1.16 |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.71–1.37 |

| ISL | |||

| Satisfaction | 0.4 | <0.001 | 0.32–0.5 |

| Sex drive | 2.27 | <0.001 | 1.78–2.9 |

| General life | 1.91 | <0.001 | 1.54–2.35 |

ISL = Index of Sex Life; CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

This study provides a contemporary, large cross-sectional sample of the sex practices and dysfunctions in a young, highly educated population of various sexual orientations. Homosexual men reported higher rates of ED; however, after adjusting for confounding variables this relationship was no longer statistically significant. On the other hand, even after adjustment, female homosexuals had lower odds of female sexual dysfunction (as defined by the FSFI) than female heterosexuals.

Although there are general differences in the occurrence of certain sexual behaviors between different groups of heterosexual and nonheterosexual individuals, it is clear from prior reports and our own data set that no sexual act is exclusive to a particular sexual orientation [22]. Exploration of sexual experience with same gendered partners is not uncommon even in individuals who later go on to endorse heterosexual orientation [1,23]. Similarly, many self-identified homosexuals report sexual encounters (both historical and current) with opposite-gender partners [21,24–26]. Our study supports these prior observations and suggests that self-professed sexual orientation is not a perfect predictor of sexual practices and/or history.

The rates of premature ejaculation (PEDT > 8) were similar among heterosexual and homosexual men (16% and 17%, P = 0.681, respectively). However, homosexual men reported a higher rate of ED relative to heterosexual men (24% vs. 12%, respectively, P = 0.019). The difference did not maintain statistical significance after adjustment for marital/domestic partnership status and relationship status as determined by SEAR. The explanation for these observations is uncertain. It is suggested that relationship stability (as would be expected in marriages or in relationships where high SEAR scores are reported) are protective against ED and that differences in these relationship factors between homosexual and heterosexual men in our cohort drive the statistically significant differences in rate of ED that we observed. Other conceivable explanations for the differences include a higher rate of organic conditions which produce ED or greater burden of psychological stress in gay men. There is evidence in the literature that psychological morbidity tends to be more common in homosexual people [11,27–29]. Whether this morbidity occurs secondary to societal stigma against homosexuals [11,30,31] or some intrinsic factor [32] has not been conclusively resolved, but it does appear that homosexuals are at greater risk of psychological distress as compared with their heterosexual peers. This consideration should be taken into account when addressing the sexual health needs of non-heterosexuals. Different interpretations of IIEF questions and/or greater expectations with respect to capacity to attain rigid erections in gay men may also drive differences in IIEF scoring between groups. This intriguing possibility merits further research; it may be hypothesized that as homosexual men engage in sex with a partner who has a penis, they may be more likely to feel a degree of competition and need for more rigid and reliable erectile capacity to match their partner.

In contrast to what was observed with respect to ED in men, homosexual women tended to have better FSFI scores and were less likely to be at high risk of FSD. The greatest differences noted between groups were higher mean scores for FSFI-pain and orgasm in lesbian women. Again, it is impossible to know the exact reason for these findings from this data set but possible explanations include: (i) lesbian women may tend to be more effective at producing orgasm in their partners; and (ii) lesbians may be less likely to engage in vigorous penetrative intercourse, which may be uncomfortable in some cases for some women. It is also of interest that sexual desire was slightly higher in lesbian and bisexual women according to the FSFI but sex drive (as determined by the ISL for women in relationships) tended to be lower in lesbians compared with the other two groups. This interesting phenomenon suggests that lesbian women in relationships have lower drive towards sexual expression (as defined by currently available instruments) despite not having significant differences in generalized interest in sex. This gives some credence to the concept of “lesbian bed death” [33] although further research is required to fully explore this. The situation of declining interest and frequency of sex in relationships is not exclusively a lesbian one [34]. It must also be considered that differences in sexual expression and activity in lesbians may not be representative of a distressing or pathological condition. It is interesting that overall satisfaction appears to be similar between women of different orientations despite some domain-specific significant differences.

With respect to specific sexual practice, heterosexual women tended to have a more limited repertoire of lifetime sexual acts. This is not unexpected as women with nonheterosexual orientations are more likely to be amenable to engaging in alternative sexual acts [35]. Lesbian women have also been reported to have a higher rate of masturbatory or autosexual activity relative to heterosexual women [36]. Both bisexual and homosexual women have a higher number of lifetime partners on average compared with heterosexual women [37–39]. Our results are generally supportive of these associations.

This study has a number of limitations. The overall response rate of approximately 3% makes our results subject to volunteer bias [40]. Individuals with liberal views on sexuality and sex practice may be more likely to take and finish a sexuality survey; the higher than expected fraction of respondents who endorsed a homosexual orientation is likely reflective of this [2,3]. However, in our opinion, the fact that a relatively high number of male homosexual subjects participated tends to give greater credence to our investigation of differences between orientation groups; a sampling of a small number of gay men compared with a large population of heterosexuals would be more likely to be inaccurate and over-estimate differences between these groups.

The survey instruments that were modified have not been validated. Use of non-validated instruments may introduce measurement bias. Taken together, it is possible that the comparative measures of association are attenuated or further from the null than stated. Another possible limitation of the study design is that we were unable to verify the accuracy of survey responses with face to face interviews. The numeric data we used as the foundation of our analysis have been validated elsewhere [13,18]. It is impossible to conclusively assess the true sexual function of subjects in this setting without face to face interview and assessment.

Although the data on prevalence rates should be interpreted with caution, the purpose of this particular analysis was not to report on prevalence of sexual orientations and sexual problems but rather on differences between students of differing sexual orientations. To this end, it was essential that we include a single instrument for all respondents of a given gender. Although a number of instruments have been developed to assess sexual function in non-heterosexual subjects, we are not aware of any one single instrument that has been validated for use in both homosexual and heterosexual subjects. Hence, although the use of non-validated instruments in this study may introduce bias with respect to raw prevalence data, it is of greater use when comparing between groups.

In clinical practice, these data may be important to consider as they indicate that sexual function is discernibly different between orientation groups. It is vital for sexual medicine clinicians to be aware of differences in sexuality and sexual practices and how these factors can affect sexual dysfunction. Homosexual men may have a relatively greater degree of distress regarding erectile capacity compared with heterosexual men, whereas despite differences in numeric FSFI scores women of varying sexual orientation seem to have similar overall rates of sexual satisfaction. Clinician understanding and acceptance of patients with diverse sexual repertoires will promote improved patient health and better patient-physician relationships.

Conclusions

There appear to be important differences and similarities in sexual function between healthy young heterosexual, bisexual, and homosexual individuals. Further investigation of how sexual orientation may be predictive of sexual health and concerns is needed to improve our ability to care for sexual problems in a diverse population.

Acknowledgments

This study received financial support from the Sexual Medicine Society of North America and publicity support from the American Medical Student Association.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: A.W. Shindel is an informal consultant for Boehringer-Ingelheim and is an editor for Yearbook of Urolgoy by Elsevier, Inc.

- Category 1

-

Conception and DesignAlan W. Shindel; Kathryn A. Ando

-

Acquisition of DataAlan W. Shindel

-

Analysis and Interpretation of DataBenjamin N. Breyer; James F. Smith; Michael L. Eisenberg; Alan W. Shindel

-

- Category 2

-

Drafting the ArticleBenjamin N. Breyer

-

Revising It for Intellectual ContentAlanW. Shindel; James F. Smith; Michael L. Eisenberg; Kathryn A. Ando; Tami S. Rowen

-

- Category 3

-

Final Approval of the Completed ArticleBenjamin N. Breyer; Alan W. Shindel; James F. Smith; Michael L. Eisenberg; Kathryn A. Ando; Tami S. Rowen

-

References

- 1.Rubio-Aurioles E, Wylie K. Sexual orientation matters in sexual medicine. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1521–1533. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00903.x. quiz 34–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pillard RC, Bailey JM. A biologic perspective on sexual orientation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1995;18:71–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey JM, Pillard RC, Neale MC, Agyei Y. Heritable factors influence sexual orientation in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:217–223. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820150067007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein I, Lue TF, Padma-Nathan H, Rosen RC, Steers WD, Wicker PA. Oral sildenafil in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Sildenafil Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1397–1404. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805143382001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rendell MS, Rajfer J, Wicker PA, Smith MD. Sildenafil for treatment of erectile dysfunction in men with diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Sildenafil Diabetes Study Group. JAMA. 1999;281:421–426. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.5.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–830. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyne K, Mandalia S, McCullough S, Catalan J, Noestlinger C, Colebunders R, Asboe D. The international index of erectile function: Development of an adapted tool for use in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. J Sex Med. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarcz S, Scheer S, McFarland W, Katz M, Valleroy L, Chen S, Catania J. Prevalence of HIV infection and predictors of high-transmission sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1067–1075. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lallemand F, Salhi Y, Linard F, Giami A, Rozenbaum W. Sexual dysfunction in 156 ambulatory HIV-infected men receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy combinations with and without protease inhibitors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:187–190. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200206010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirshfield S, Chiasson MA, Wagmiller RL, Jr, Remien RH, Humberstone M, Scheinmann R, Grov C. Sexual dysfunction in an internet sample of U.S. men who have sex with men. J Sex Med. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau JT, Kim JH, Tsui HY. Prevalence and sociocultural predictors of sexual dysfunction among Chinese men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2766–2779. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bancroft J, Carnes L, Janssen E, Goodrich D, Long JS. Erectile and ejaculatory problems in gay and heterosexual men. Arch Sex Behav. 2005;34:285–297. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-3117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cappelleri JC, Rosen RC, Smith MD, Mishra A, Osterloh IH. Diagnostic evaluation of the erectile function domain of the International Index of Erectile Function. Urology. 1999;54:346–351. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Symonds T, Perelman M, Althof S, Giuliano F, Martin M, Abraham L, Crossland A, Morris M, May K. Further evidence of the reliability and validity of the premature ejaculation diagnostic tool. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19:521–525. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Symonds T, Perelman MA, Althof S, Giuliano F, Martin M, May K, Abraham L, Crossland A, Morris M. Development and validation of a premature ejaculation diagnostic tool. Eur Urol. 2007;52:565–573. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cappelleri JC, Althof SE, Siegel RL, Shpilsky A, Bell SS, Duttagupta S. Development and validation of the Self-Esteem And Relationship (SEAR) questionnaire in erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16:30–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, D’Agostino R., Jr The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): Cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31:1–20. doi: 10.1080/00926230590475206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chevret M, Jaudinot E, Sullivan K, Marrel A, De Gendre AS. Quality of sexual life and satisfaction in female partners of men with ED: Psychometric validation of the Index of Sexual Life (ISL) questionnaire. J Sex Marital Ther. 2004;30:141–155. doi: 10.1080/00926230490262339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tracy JK, Junginger J. Correlates of lesbian sexual functioning. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16:499–509. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diamant AL, Schuster MA, McGuigan K, Lever J. Lesbians’ sexual history with men: Implications for taking a sexual history. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2730–2736. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.22.2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeffries WLt. A comparative analysis of homosexual behaviors, sex role preferences, and anal sex proclivities in latino and non-latino men. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38:765–778. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diamond LM. Was it a phase? Young women’s relinquishment of lesbian/bisexual identities over a 5-year period. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:352–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pathela P, Hajat A, Schillinger J, Blank S, Sell R, Mostashari F. Discordance between sexual behavior and self-reported sexual identity: A population-based survey of New York City men. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:416–425. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-6-200609190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zule WA, Bobashev GV, Wechsberg WM, Costenbader EC, Coomes CM. Behaviorally bisexual men and their risk behaviors with men and women. J Urban Health. 2009;86(Suppl 1):48–62. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9366-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks KD, Quina K. Women’s sexual identity patterns: Differences among lesbians, bisexuals, and unlabeled women. J Homosex. 2009;56:1030–1045. doi: 10.1080/00918360903275443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, Nazareth I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:1270–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:2275–2281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian. gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1869–1876. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zietsch BP, Verweij KJ, Bailey JM, Wright MJ, Martin NG. Sexual orientation and psychiatric vulnerability: A twin study of neuroticism and psychoticism. Arch Sex Behav. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9508-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Rosmalen-Nooijens KA, Vergeer CM, Lagro-Janssen AL. Bed death and other lesbian sexual problems unraveled: A qualitative study of the sexual health of Lesbian women involved in a relationship. Women Health. 2008;48:339–362. doi: 10.1080/03630240802463343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brewis A, Meyer M. Marital coitus across the life course. J Biosoc Sci. 2005;37:499–518. doi: 10.1017/s002193200400690x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richters J, de Visser RO, Rissel CE, Grulich AE, Smith AM. Demographic and psychosocial features of participants in bondage and discipline, “sadomasochism” or dominance and submission (BDSM): Data from a national survey. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1660–1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burleson MH, Trevathan WR, Gregory WL. Sexual behavior in lesbian and heterosexual women: Relations with menstrual cycle phase and partner availability. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:489–503. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grulich AE, de Visser RO, Smith AM, Rissel CE, Richters J. Sex in Australia: Homosexual experience and recent homosexual encounters. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2003;27:155–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2003.tb00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisenberg M. Differences in sexual risk behaviors between college students with same-sex and opposite-sex experience: Results from a national survey. Arch Sex Behav. 2001;30:575–589. doi: 10.1023/a:1011958816438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostovich JM, Sabini J. How are sociosexuality, sex drive, and lifetime number of sexual partners related? Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30:1255–1266. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.AAMC. Total U.S. Medical School Enrollment by Race and Ethnicity within Sex, 2002–2009. [accessed February 26, 2010];2009 Available at: http://www.aamc.org/data/facts/enrollmentgraduate/table28-enrllbyraceeth0209.pdf. [Google Scholar]