Abstract

Background

Pre-infarction angina may act as a clinical surrogate of ischemic preconditioning that may reduce infarct size and improve mortality in the setting of thrombolytic therapy for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). However, the benefits of pre-infarction angina in the setting of primary PCI with stenting is inconclusive due to the greater achievement of infarct artery patency and speed of reperfusion.

Methods and Results

To identify a homogeneous population, we performed a retrospective analysis of 1031 patients admitted with a first STEMI with ischemic times between 1 and 6 hours who received primary PCI. We identified 245 patients who had occluded arteries on presentation of which 79 patients had documented pre-infarction angina defined as chest pain within 24 hours of infarction. Infarct size was measured as the peak CK level, a metric supported in a subgroup by late enhancement on cardiac MRI. Patients with pre-infarction angina (n=79) had a 50% reduction in infarct size compared to those patients without pre-infarction angina (n=166) by both peak CK (1094 ± 75 IU/L vs. 2270 ± 102 IU/L, p<0.0001) and CK area-under-curve (18,420 ± 18,941 vs. 36,810 ± 21,741 IU-hr / L, p <0.0001) despite having identical ischemic times (185 ± 8 min vs 181 ± 5 min, p=0.67) and angiographic area-at-risk (24.1 ± 1.2% vs. 25.3 ± 0.9%, p=0.43). There was an absolute 4% improvement in left-ventricular ejection fraction prior to discharge in those patients with pre-infarction angina (p < 0.02).

Conclusion

The occurrence of pre-infarction angina is associated with significant myocardial protection in the setting of primary PCI with stenting during STEMI. Because pre-infarction angina is relatively common, it is important that these patients be identified in clinical trials investigating therapies designed to reduce reperfusion injury and infarct size.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, stents, angina, reperfusion

Ischemic preconditioning (IP) is the phenomenon by which transient episodes of ischemia protect the myocardium against a subsequent episode of prolonged ischemia [1]. IP represents the most potent form of myocardial protection yet discovered. In humans, angina pectoris preceding myocardial infarction is thought to represent a clinical correlate of ischemic preconditioning. Multiple studies have shown that pre-infarction angina prior to ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) limits infarct size, improves left ventricular function and enhances survival [2–9]. However, the majority of these studies were performed when reperfusion was achieved with thrombolysis (2–7). To date, significant uncertainty remains as to whether the benefit of this phenomenon translates to patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). While one small study demonstrated decreased infarct size in patients with pre-infarction angina [8], two larger trials showed no protective effect in the setting of primary PCI with angioplasty alone, or in conjunction with stenting [10, 11]. However, confounding factors that affect infarct size such as collateral blood flow and accurate measurements of ischemic time and myocardial area-at-risk (AAR) were not accounted for in these trials. Thus, the true benefit of pre-infarction angina in the primary PCI era remains unclear. To clarify if pre-infarction angina reduces infarct size following a well-defined duration of myocardial ischemia, we analyzed its protective effect in 245 patients with well defined ischemic times who presented with an occluded coronary artery during primary PCI in the setting of STEMI.

Methods

Study Design

A retrospective analysis was performed on all patients who were admitted to the Minneapolis Heart Institute at Abbott Northwestern Hospital from January 2006 through September 2010 as part of the Level 1 Acute MI program (12). This is a regionalized transfer network developed for primary PCI involving 31 community hospitals and emergency departments throughout Minnesota and Western Wisconsin. Patients are enrolled in a prospective registry with detailed baseline clinical, time to treatment, laboratory, angiographic and follow-up data.

A total of 1031 patients were identified in the Level 1 Program database who presented with STEMI and had well defined ischemic times between 1 and 6 hours. The ischemic time was defined as the time difference between onset of chest pain to restoration of flow following the first balloon inflation during primary PCI. All patients were pre-medicated with aspirin (325 mg), clopidogrel (600mg), heparin (60 Units /kg) or bivalirudin (0.75 mg/kg bolus followed by 1.75 mg/kg-hr) and underwent routine primary PCI and stenting of the culprit vessel. The vast majority of patients received drug-eluting stents.

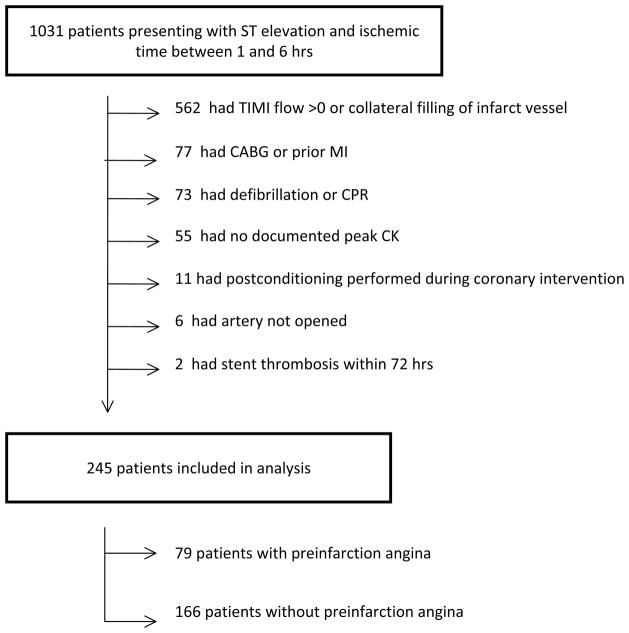

A total of 786 were excluded from further analysis as they met at least one of the following exclusion criteria: TIMI flow > 0 prior to coronary intervention or presence of visible collaterals to infarct vessel (n=562), prior CABG or MI in same vascular distribution (n=77), cardiac arrest requiring more than 1 shock or CPR (n=73), peak of cardiac enzymes was not recorded (n=55), postconditioning performed during coronary intervention (n=11), vessel could not be opened (n=6), or acute stent thrombosis within 72hrs (n=2). A total of 245 patients including 166 patients without pre-infarction angina and 79 patients with pre-infarction angina were included in the final analysis (Fig.1). Pre-infarction angina was defined as one or more occurrence of chest pain similar to their STEMI pain that occurred within 24 hours on infarct onset.

Figure 1.

Study Design: Of 1031 patients presenting with ST elevation and an ischemic times between 1 and 6 hrs, 786 patients were excluded based on pre-specified exclusion criteria. Patients could have more than 1 reason for exclusion but only 1 per patient is noted in the diagram.

Measurement of Infarct Size

The peak creatine kinase (CK) level was used as a surrogate of infarct size as previously validated by us (13) and others (14,15) using delayed enhancement measurements with cardiac MRI. Measurements of CK were performed on presentation and every 6 to 8 hrs for 24 to 48 hours following reperfusion with the highest value designated as the peak CK. Measurement of left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by echocardiography was obtained in 220 patients within 48 hours following reperfusion. Confirmatory measurements of infarct size difference between groups was also performed by measuring the CK area-under-curve (AUC).

Measurement of the Angiographic Area at Risk (AAR)

The angiographic AAR was calculated for each patient using the modified Alberta Provincial Project for Outcome Assessment in Coronary Heart Disease (APPROACH) score (16). This method is based on previous pathological studies estimating the percentage of myocardium perfused by each coronary artery. For each patient, an area at risk score, expressed as percentage of myocardium, was calculated based on the location of the culprit lesion in the infarct artery (proximal, mid, distal) in relation to major side branches and dominance of the vessel. This method has been previously validated by MRI measurements of AAR by us (13) and others (17).

Statistical Analysis

Comparison of infarct size, ischemic times, area at risk and left ventricular ejection fraction was performed by two-tailed Student t test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to determine relationship between ischemic time and peak CK. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Quantile-Quantile plot (QQ plot) was constructed by calculating the quantiles of the PIA population and plotting the corresponding EF and CK values on the x-axis of the respective graphs. The y-axis shows the EF and CK values of the same quantiles in the non-PIA population. Graph Pad Prism was used for all statistical calculations.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Pre-infarction angina within 24 hours of admission was present in 79 patients and absent in 166 patients. As summarized in the Table there were no significant differences in terms of age, sex, BMI, ischemic time and classical risk factors for CAD.

Table. Patient Demographics.

Baseline characteristics of patients who had pre-infarction angina prior to STEMI compared to patients without pre-infarction angina.

| No Pre-Infarction Angina (n=166) | Pre-Infarction Angina (n=79) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs), mean(SD) | 58.9 ± 12.5 | 60.7 ± 12.7 | 0.31 |

| Males, (%) | 133 (80.1) | 59 (74.7) | 0.33 |

| Hypertension, (%) | 79 (47.6) | 39 (50.0) | 0.73 |

| Dyslipidemia, (%) | 83 (50.9) | 39 (49.4) | 0.82 |

| Diabetes, (%) | 22 (13.3) | 10 (12.7) | 0.90 |

| Culprit Artery | |||

| LAD, (%) | 65 (39.2) | 32 (40.5) | 0.69 |

| RCA, (%) | 73 (44.0) | 37 (46.8) | |

| LCx, (%) | 28 (16.9) | 10 (12.7) | |

| Killip Class | |||

| 0/1, (%) | 149 (89.8) | 74 (93.7) | 0.65 |

| 2/4, (%) | 17 (10.2) | 5 (6.3) | |

| CK AUC (IU-hr / L) | 36,810±21,741 | 18,420±18,941 | p < 0.0001 |

| Time to peak CK post- reperfusion (min) | 550 ± 29 | 581 ± 42 | 0.54 |

| Number of stents placed | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.58 |

| Fluoroscopy time (min) | 11.9 ± 0.6 | 11.9 ± 1.0 | 0.97 |

| Contrast use (ml) | 168 ± 4 | 164 ± 7 | 0.64 |

| Bivalirudin (%) | 10.6 ± 2 | 15.6 ± 4 | 0.28 |

| GP IIB IIIA (%) | 78.1 ± 3.3 | 77.9 ± 4.7 | 0.97 |

| Aspiration Thrombectomy (%) | 38.1 ± 3.9 | 43.6 ± 5.7 | 0.42 |

AUC = CK area-under-curve; GP = glycoprotein;

Primary PCI Characteristics

There were no differences between the two groups in regards to fluoroscopy time, contrast use and number of stents delivered. A similar number of patients in both groups received glycoprotein IIB IIIA receptor antagonists and aspiration thrombectomy (Table).

Infarct Size, Ischemic Times and Angiographic Area-at-Risk

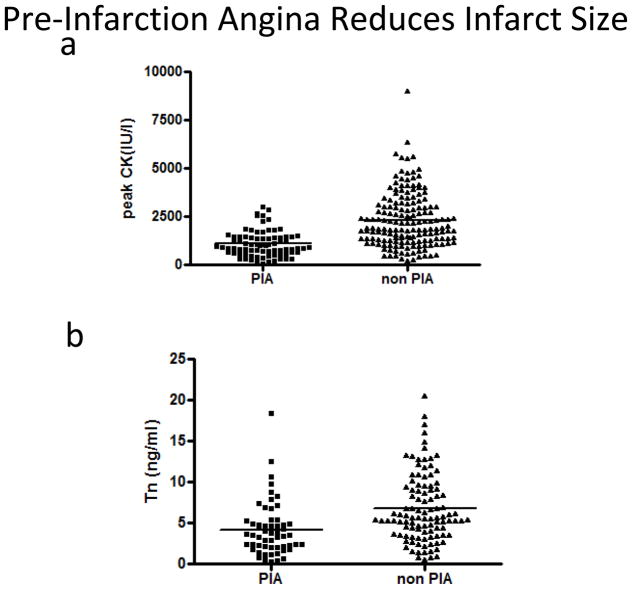

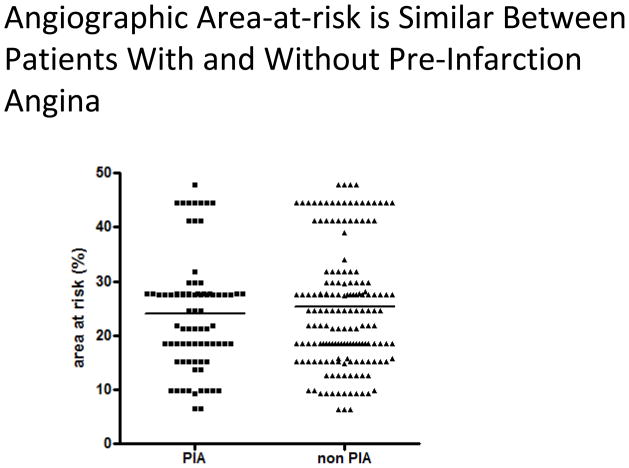

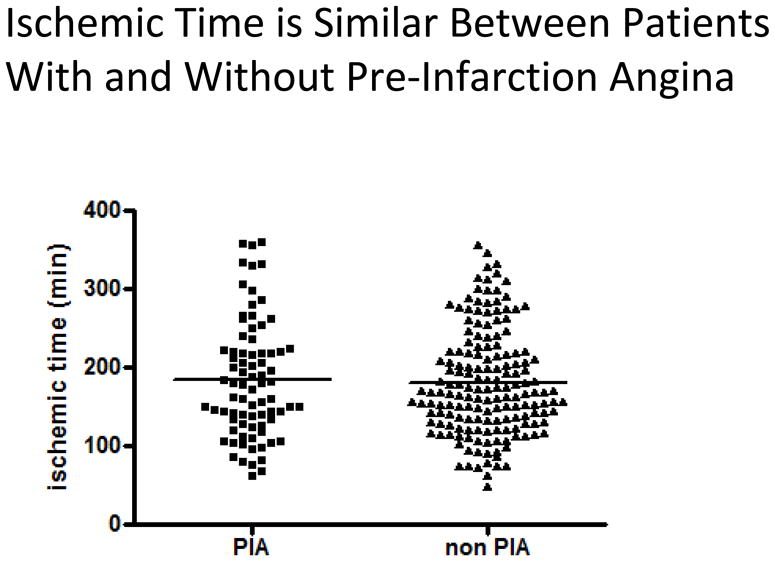

Infarct size was significantly lower in patients with pre-infarction angina compared to those without (1094 ± 75 IU/l vs. 2270 ± 102 U/l, p<0.0001) (Fig 2a). Similar results were observed when peak troponin T was used as a marker for myocardial damage (4.2 ± 0.4ng/ml vs. 6.7 ± 0.4ng/ml, p<0.0001) (Fig 2b). CK AUC was significantly reduced in the patients with pre-infarction angina (18,420 ± 18,941 vs 36,810 ± 21,741 IU-hr / L, p< 0.0001) (Table). Ischemic times were similar between the two groups (185 ± 8 min vs 181 ± 5 min, p=0.67) (Fig 3) and no difference in the AAR was observed between patients with and without pre-infarction angina (24.1 ± 1.2% vs. 25.3 ± 0.9%, p=0.43) (Fig4).

Figure 2.

Ischemic time according to the presence or absence or pre-infarction angina: Ischemic time was plotted according to the presence of absence of pre-infarction angina. Mean ischemic time, indicated by horizontal line, is not significantly different between patients with and without pre-infarction angina (185 ± 8min vs. 181 ± 5, p=0.67, Student’s t-test).

Figure 3.

Peak CK and peak Troponin I according to the presence or absence or pre-infarction angina: Peak CK (a) and peak Troponin I (b) were plotted according to the presence or absence of pre-infarction angina. Mean peak CK, indicated by horizontal line, is significantly different in patients with and without pre-infarction angina 1094+/−75 IU/l vs. 2270+/−102 IU/l (p<0.0001, Student’s t-test). Mean peak Troponin I was 4.2+/−0.4 ng/ml vs.6.7+/−0.4 ng/ml, p<0.0001).

Figure 4.

Area-at-risk according to the presence or absence or pre-infarction angina: Area-at-risk was assessed angiographically by ACCORD score and was plotted according to the presence of absence of pre-infarction angina. Mean area-at-risk, indicated by horizontal line, is not significantly different between patients with and without pre-infarction anginna (24.1+/− 1.2% vs. 25.3+/− 0.9%, p=0.43, Student’s t-test).

Measurement of Left Ventricular Function

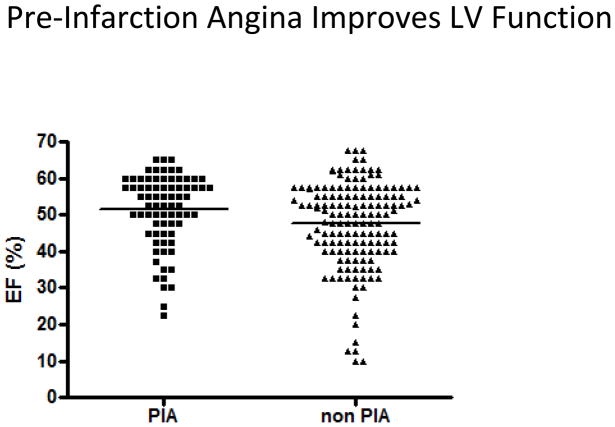

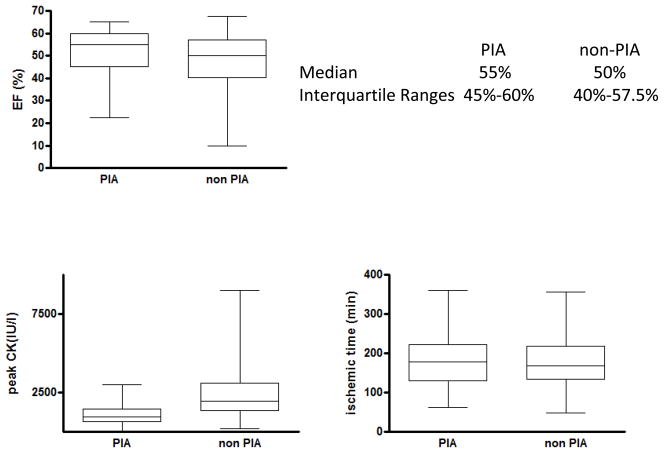

We investigated if the significant difference in infarct size in patients with and without pre-infarction angina was associated with a significant difference in left-ventricular function. A total of 220 patients had measurements of LVEF obtained within 2 days of STEMI. Ejection fraction was 4% higher in patients with pre-infarction angina (51.4 ± 1.1%, median = 55%, IQR = 45–60%) compared to patients without (47.5 ± 1.0%, median = 50%, IQR = 40–57.5%) (p<0.02) (Fig.5–6).

Figure 5.

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) according to the presence or absence of pre-infarction angina: LVEF was plotted according to the presence of absence of pre-infarction angina. Mean LVEF, indicated by horizontal line, was significantly higher in patients with pre-infarction angina compared to patients without (51.4 ± 1.1% vs. 47.5 ± 1.0%, p<0.02, Student’s t-test).

Figure 6.

Medians and Interquartile ranges for LVEF (%), peak CK (IU / L) and ischemic times (min) in patients with and without pre-infarction angina.

To determine if PIA acts to limit large infarctions we compared the two populations using a Q-Q plot of the peak CK values and LVEF. Data points on the CK plot follow a straight line with a slope >1. This suggests that the two populations have a similar distribution and differ in scale only. It indicates that the protective effect of PIA is present regardless of infarct size. The LVEF curve is also straight except for the bottom-left of the curve where the slope is greater. This suggests that the distribution of the LVEF in the non- PIA population is skewed to the left showing a comparatively larger number of low EF patients (Supplemental Figure 2)

Protective Effect of Pre-infarction Angina is Dependent on Ischemic Time

Previous studies showed improved clinical outcome in patients with pre-infarction angina only if reperfusion by thrombolysis occurred after 2 hours of chest pain whereas no beneficial effect was seen in early reperfusion (4). We therefore investigated if a similar time dependence of the protective effect of pre-infarction angina in patients treated with PCI can be seen. We plotted ischemic time against peak CK and performed linear regression. In patients without pre-infarction angina, we observed a linear increase in infarct size with increasing ischemic time (r= 0.35, p<0.0001) (Fig 7a). In contrast, patients with pre-infarction angina demonstrated no correlation between ischemic time and peak CK within 6 hours of ischemia (r=0.07, p=0.53) (Fig 7b). This suggests that the protection potentially conferred by pre-infarction angina may extend for at least 6 hours of ischemia and becomes more protective with increasing ischemic times.

Figure 7.

Relationship of ischemic time and peak CK in patients with and without pre-infarction angina: Peak CK was plotted against ischemic time in patients with (a) and without (b) pre-infarction angina. Linear regression was performed as indicated by solid line. The slope of the linear regression curve is significantly different from 0 in non-pre-infarction angina patients (6.1 ± 1.6, p<0.001) but not in patients with pre-infarction angina (0.7 ± 1.0, p=0.49).

Discussion

Our results suggest that pre-infarction angina is associated with significant myocardial protection in the setting of primary PCI for STEMI. Multiple mechanisms have been proposed to account for these protective effects including accelerated thrombolysis (18), opening of pre-existing collateral vessels (19), reduced microvascular obstruction (20) and a myocardial conditioning effect similar to IP. Several clinical studies have demonstrated significant cardioprotective effects of pre-infarction angina in the setting of thrombolytic therapy including reduced infarct size (2–7, 9, 21) and improved short and long-term mortality (22). In contrast, its beneficial effect in patients treated with primary PCI with and without stenting has been inconclusive. A small, prospective study by Ottani et al (8) in 22 patients with anterior STEMI undergoing primary PCI with stenting, demonstrated that the occurrence of angina within 24 hours of infarction significantly reduced infarct size and improved myocardial salvage by 32% that translated into an 8% improvement in LVEF at 6 months. Kosuge et al (23) presented data from the Japan Acute Coronary Syndrome Study in 913 STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI (78% stenting) with ischemic times up to 12 hours. Pre-infarction angina described as ≤ 30 mins of chest pain within 24 hrs of MI was observed in 358 patients (39%). Patients with pre-infarction angina and anterior STEMIs had significant reductions in infarct size and improved mortality compared to those without pre-infarction angina. However, two other studies observed no clinical benefit of pre-infarction angina. Zahn et al (10) analyzed 774 STEMI patients from the German Myocardial Infarction Registry treated with primary PCI without stenting who had ischemic durations of up to 12 hours. Pre-infarction angina defined as any episode of chest pain within 4 weeks of infarction occurred in 69% of all patients. They observed no clinical benefit of pre-infarction angina in regards to mortality or development of heart failure suggesting that its benefit was potentially overshadowed in the setting of primary angioplasty due to the much greater achievement of rapid reperfusion compared to thrombolytic therapy. Tomodo and Aoki (11) presented data from 613 STEMI patients with up to 12 hours of ischemia treated with thrombolysis or medical therapy alone (Group 1, n=306) or primary PCI (Group 2, n=307). In patients with pre-infarction angina, defined as chest pain within 24 hours of infarction, only those patients with pre-infarction angina in Group 1 demonstrated significant reductions in peak CK and development of heart failure while there was no additional benefit observed in Group 2 patients that had pre-infarction angina.

In contrast, in a homogeneous population with similar ischemic times and myocardial AAR, we observed a greater than 50% reduction in infarct size associated with patients with pre-infarction angina who underwent primary PCI, suggesting a powerful myocardial protective effect of this corellate of IP. It is likely that patient selection and study design in previous studies significantly contributed to the inconsistent benefits of pre-infarction angina. Our highly selected patient cohort was chosen by design in order to more accurately determine the benefits of pre-infarction angina on infarct size reduction in STEMI. To achieve this, we excluded patients with previous myocardial infarction, infarct artery patency prior to PCI (TIMI ≥ 1) or visible collateral blood flow to the infarct region. Importantly, this potent infarct- sparing mechanism (19) was never accounted for in any of the other trials with the exception of the small study of Ottani et al (8). Ischemic duration was further limited to 6 hours, since the benefit of IP may be lost with prolonged ischemic duration (1). Using these selection criteria, we observed a linear increase in infarct size with ischemic duration in the control group that was abrogated in those patients with pre-infarction angina (Figure 6).

These observations may have implications for studies investigating novel therapies to reduce reperfusion injury and infarct size in the setting of STEMI. It is remarkable that pre-infarction angina is rarely accounted for in clinical trials despite its high prevalence, which may exceed 50% of all patients presenting with STEMI in some trials (2). This could contribute to the largely negative outcomes of clinical trials in this area, despite encouraging pre-clinical data in animals (24).

While eventual reperfusion is essential for the protective effect of pre-infarction angina, the time course is less well defined. Benefits of pre-infarction angina were mainly associated with patients who had intermediate or late reperfusion (4). Our study shows a similar pattern. While myocardial damage increased with ischemic duration in patients without pre-infarction angina, no such correlation was observed in those patients with pre-infarction angina. While infarct size was smaller in patients with pre-infarction angina regardless of ischemic time, the difference were most pronounced in prolonged ischemic time suggesting that the protective effect of pre-infarction angina may last for at least 6 hours. This also implies that the benefit of late PCI may be greater in patients with pre-infarction angina as more myocardium can be salvaged.

Study Limitations

We cannot completely rule out that patients with pre-infarction angina had spontaneous episodes of reperfusion during their STEMI that may have reduced their infarct size despite all patients having an occluded artery on presentation. The finding that the time to peak CK was similar between the two groups argues against this possibility. However, the only way to completely exclude this would have patients undergo continuous ST-segment monitoring during their STEMI which was not feasible in this study. We did not include patients with short ischemic times (< 2hrs) as the relationship with infarct size in patients with PIA may reflect difficulty in establishing the true ischemic time as much as a physiologic effect.

Conclusions

This study represents the most detailed analysis to date describing the potential myocardial protective effects of pre-infarction angina in patients with STEMI undergoing primary PCI with stenting. These findings may have implications for clinical trials investigating agents designed to reduce reperfusion injury and infarct size. Because pre-infarction angina is relatively common and may result in significant myocardial protection, it is imperative that patients with pre-infarction angina be identified in clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

What is Known

Chest pain in the 24 hours prior to myocardial infarction called pre-infarction angina is common.

Pre-infarction angina is thought to reduce infarct size by a preconditioning mechanism.

In the thrombolytic era, pre-infarction angina was shown to limit infarct size, and improve LV function and survival.

It is not known if pre-infarction angina remains protective in the era of primary PCI where reperfusion can be achieved more quickly.

What this Article Adds

This article is the largest cohort to date to examine the effect pre-infarction angina in patients with STEMI in the setting of primary PCI with well-defined ischemic times and angiographic areas-at-risk..

The occurrence of pre-infarction resulted in a 50% reduction in infarct size compared to patients without pre-infarction angina despite having similar ischemic times and angiographic areas-at-risk.

Patients with pre-infarction angina had improved ejection fractions at discharge compared to those patients without pre-infarction angina.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

Supported in part by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute to JHT (1-RO1-HL103927).

This study was presented in abstract form at the 2011 Scientific Sessions of the American Heart Association, Orlando FL. The authors would like to thank Ross Garberich for his statistical assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–36. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anzai T, Yoshikawa T, Asakura Y, Abe S, Akaishi M, Mitamura H, Handa S, Ogawa S. Preinfarction angina as a major predictor of left ventricular function and long-term prognosis after a first Q wave myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:319–27. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)80002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahr RD, Leino EV, Christenson RH. Prodromal unstable angina in acute myocardial infarction: prognostic value of short- and long-term outcome and predictor of infarct size. Am Heart J. 2000;140:126–33. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.106641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishihara M, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, Shimatani Y, Kurisu S, Nishioka K, Umemura T, Nakamua S, Yoshida K. Effect of prodromal angina pectoris on altering the relation between time to reperfusion and outcomes after a first anterior wall acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:128–32. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kloner RA, Shook T, Antman EM, Cannon CP, Przyklenk K, Yoo K, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. Prospective temporal analysis of the onset of preinfarction angina versus outcome: an ancillary study in TIMI-9B. Circulation. 1998;97:1042–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.11.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kloner RA, Shook T, Przyklenk K, Davis VG, Junio L, Matthews RV, Burstein S, Gibson M, Poole WK, Cannon CP, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. Previous angina alters in-hospital outcome in TIMI 4. A clinical correlate to preconditioning? Circulation. 1995;91:37–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Napoli C, Liguori A, Chiariello M, Di leso N, Condorelli M, Ambrosio G. New-onset angina preceding acute myocardial infarction is associated with improved contractile recovery after thrombolysis. Eur Heart J. 1998;19:411–9. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1997.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ottani F, Galli M, Zerboni S, Galvani M. Prodromal angina limits infarct size in the setting of acute anterior myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1545–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ottani F, Galvani M, Ferrini D, Sorbello F, Limonetti P, Pantoli D, Rusticali F. Prodromal angina limits infarct size. A role for ischemic preconditioning. Circulation. 1995;91:291–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zahn R, Schiele R, Schneider S, Gitt AK, Seidl K, Bossaller C, Schuler G, Gottwik M, Altmann E, Rosahl W. Effect of preinfarction angina pectoris on outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty (results from the Myocardial Infarction Registry. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomoda H, Aoki N. Comparison of protective effects of preinfarction angina pectoris in acute myocardial infarction treated by thrombolysis versus by primary coronary angioplasty with stenting. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:621–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry TD, Sharkey SW, Burke N, Chavez IJ, Graham KJ, Henry CR, Lips DL, Madison JD, Menssen KM, Mooney MR, Newell MC, Pedersen WR, Poulose AK, Traverse JH, Unger BT, Wang YL, Larson DM. A regional system to provide timely access to percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:721–728. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.694141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reiter R, Swingen C, Moore L, Henry TD, Traverse JH. Circadian dependence of infarct size and left-ventricular function following ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2012;110:105–110. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.254284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chia S, Senatore F, Raffel OC, Lee H, Wackers FJT, Jang I-K. Utility of cardiac biomarkers in predicting infarct size, left ventricular function, and clinical outcome after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:415–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haase J, Bayer R, Hackenbroch M, Storger H, Hofmann M, Schwarz C-E, Reinemer H, Schwarz F, Ruef J, Sommer T. Relationship between size of myocardial infarctions assessed by delayed contrast-enhanced MRI after primary PCI, biochemical markers, and time to intervention. J Interv Cardiol. 2004;17:367–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2004.04078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham MM, Faris PD, Ghali WA, Galbraith D, Norris CM, Badry JT, Mitchell LB, Curtis MJ, Knudtson ML. Validation of three myocardial jeopardy scores in a population-based cardiac catheterization cohort. Am Heart J. 2001;142:254–61. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.116481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ortiz-Perez JT, Meyers SN, Lee DC, Kansal P, Klocke FJ, Holly TA, Davidson CJ, Bonow RO, Wu E. Angiographic estimates of myocardium at risk during acute myocardial infarction: validation study using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1750–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andreotti F, Pasceri V, Hackett DR, Davies GJ, Haider AW, Maseri A. Preinfarction angina as a predictor of more rapid coronary thrombolysis in patients with acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:7–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601043340102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billinger M, Fleisch M, Eberli FR, Garachemani A, Meier B, Seiler C. Is the development of myocardial tolerance to repeated ischemia in humans due to preconditioning or collateral recruitment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1027–35. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00674-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jessel L, Morel O, Ohlmann P, Germain P, Faure A, Jahn PM, Coulbois PM, Chauvin M, Bareiss P, Roul G. Role of pre-infarction angina and inflammatory status in the extent of microvascular obstruction detected by MRI in myocardial infarction patients treated by PCI. Int J Cardiol. 2007;121:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller DW, Topol EJ, Califf, Sigmon KN, Gormon L, George BS, Kereiakes DJ, Lee KL, Ellis SG. Relationship between antecedent angina pectoris and short-term prognosis after thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Thrombolysis and Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (TAMI) Study Group. Am Heart J. 1990;119:224–31. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(05)80008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christenson RH, Leino EV, Giugliana RP, Bahr RD. Usefulness of prodromal unstable angina pectoris in predicting better survival and smaller infarct size in acute myocardial infarction (The InTIME-II prodromal symptoms substudy) Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:598–600. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00732-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosuge M, Kimura K, Kojima S, Sakamoto T, Ishihara M, Asada Y, Tei C, Miyazaki S, Sonoda M, Tsuchihashi K, Yamagishi M, Ikeda Y, Shirai M, Hiraoka H, Inoue T, Saito F, Ogawa H. Effects of pre-infarction angina pectoris on infarct size and in-hospital mortality after coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:840–843. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00896-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolli R, Becker L, Gross G, Mentzer R, Balshaw D, Lathrop DA. Myocardial protection at a crossroads: the need for translation into clinical therapy. Circ Res. 2004;95:125–34. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000137171.97172.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.