Abstract

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a necroinflammatory liver disease of unknown etiology. The disease is characterized histologically by interface hepatitis, biochemically by increased aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels, and serologically by increased autoantibodies and immunoglobulin G levels. Here we discuss AIH in a previously healthy 37-year-old male with highly elevated serum levels of soluble interleukin-2 receptor and markedly enlarged hepatoduodenal ligament lymph nodes (HLLNs, diameter, 50 mm). Based on these observations, the differential diagnoses were AIH, lymphoma, or Castleman’s disease. Liver biopsy revealed the features of interface hepatitis without bridging fibrosis along with plasma cell infiltration which is the typical characteristics of acute AIH. Lymph node biopsy revealed lymphoid follicles with inflammatory lymphocytic infiltration; immunohistochemical examination excluded the presence of lymphoma cells. Thereafter, he was administered corticosteroid therapy: after 2 mo, the enlarged liver reached an almost normal size and the enlarged HLLNs reduced in size. We could not find AIH cases with such enlarged lymph nodes (diameter, 50 mm) in our literature review. Hence, we speculate that markedly enlarged lymph nodes observed in our patient may be caused by a highly activated, humoral immune response in AIH.

Keywords: Autoimmune hepatitis, Humoral immune response, Hepatoduodenal ligament lymph nodes, Corticosteroid, Hepatomegaly

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is histologically characterized by inflammatory cell infiltration (plasma cell-dominant), piecemeal necrosis in the portal area of the liver, hypergammaglobulinemia, and autoantibodies in the serum[1,2]. The onset is frequently insidious with nonspecific symptoms; however, the clinical spectrum is wide, ranging from an asymptomatic presentation[3,4] to an acute severe disease such as fulminant hepatitis[5,6]. The diagnosis is based on typical histological changes in the liver and the presence of autoantibodies in the serum after excluding other etiologies that cause liver diseases. Because there can be a wide range of presentations at onset, a prompt diagnosis is required to achieve a favorable prognosis.

Here we report the case of a previously healthy patient who developed acute hepatitis with markedly enlarged hepatoduodenal ligament lymph nodes (HLLNs).

CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old male presented to a hospital with the complaints of general fatigue, loss of appetite, and icterus for the past two weeks. He was a non-smoker and non-drinker with no relevant medical history. Until that date, blood biochemistry (including liver function) was normal. He gave no history of previous trauma, indulgence in casual sex, or illicit drug abuse. He was suffering from mild atopic dermatitis that was not treated. Laboratory examination revealed a high serum total bilirubin (T-Bil) levels of 13.8 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels of 828 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels of 823 IU/L and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels of 1055 IU/L. In addition, the HLLNs were markedly enlarged along with elevated serum levels of the soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R, 2167 U/mL).

Eventually, he was referred to our hospital. Upon admission, his blood pressure, pulse rate, and body temperature were normal. Neurological examination did not reveal hepatic encephalopathy; however, severe icterus was observed. The liver was palpable > 5 cm below the costal margin and was smooth and hard. Mild lymphadenopathy of the axillary lymph nodes (diameter ≤ 10 mm) was observed, which were palpable but asymptomatic.

The laboratory data collected at the time of admission are summarized in Table 1. Following were the important parameters recorded for evaluation: AST, 1068 IU/L; ALT, 696 IU/L; T-Bil, 15.6 mg/dL; prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR), 1.2; immunoglobulin (Ig) G, 3814 mg/dL; anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) × 2560; anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA)-negative; anti-smooth muscle antibody-negative; serum sIL-2R, 2550 U/mL.

Table 1.

Laboratory data of the patient on admission

| WBC | 2460/μL | IL-2 | 1.5 U/mL |

| Neut | 65% | IL-6 | 7.4 pg/mL (0-4.0 pg/mL) |

| Lym | 20% | IgG | 3814 mg/dL (820-1740 mg/dL) |

| Mono | 13% | IgA | 298 mg/dL (90-400 mg/dL) |

| RBC | 313 × 104/μL | IgM | 1738 mg/dL (31-200 mg/dL) |

| Hb | 10.1 g/dL | IgG4 | 97 mg/dL (4-108 mg/dL) |

| Plt | 17.5 × 104/μL | ANA | × 2560 |

| PT-INR | 1.2 | AMA | (-) |

| TP | 8.9 g/dL | Antismooth muscle antibody | (-) |

| Alb | 2.7 g/dL | ||

| T-Bil | 15.6 mg/dL | sIL2R | 2550 U/mL |

| D-Bil | 12.4 mg/dL | HA IgM-Ab | (-) |

| ALP | 847 IU/L | HBsAg | (-) |

| γ-GTP | 91 IU/L | HBcAb | (-) |

| AST | 1068 IU/L | IgM-HBcAb | (-) |

| ALT | 696 IU/L | HCVAb | (-) |

| LDH | 455 IU/L | HCV-RNA | (-) |

| ChE | 130 IU/L | Fourth-generation HIV screening assay | (-) |

| Tch | 146 mg/dL | ||

| CPK | 63 IU/L | ||

| CRP | 0.70 mg/dL | EBV VCA-IgM | (-) |

| FBS | 95 mg/dL | EBV VCA-IgG | (+) |

| Ferritin | 504 ng/mL | CMV-IgM | 2.06 |

| Serum copper | 177 μg/dL | CMV-IgG | (-) |

| Ceruloplasmin | 40.2 mg/dL | pp65 antigenemia method | (-) |

WBC: White blood cell; RBC: Red blood cell; PT/INR: Prothrombin time/international normalized ratio; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; LDH: Lactic dehydrogenase; CPK: Creatine phosphokinase; CRP: cAMP receptor protein; FBS: Fatal bovine serum; IL: Interleukin; ANA: Anti-nuclear antibody; AMA: Anti-mitochondrial antibody; sIL-2R: Soluble interleukin-2 receptor; Ig: Immunoglobulin; HA-IgM: Hepatitis A virus IgM; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HBcAb: Anti-hepatitis B core antibody; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; EBV VCA: Epstein-barr virus viral capsid antigen; CMV: Cytomegalovirus; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus.

Extensive serological screening was conducted to identify liver injury caused by viral infection. Subsequently, the following tests were negative: hepatitis A virus IgM (HA-IgM), hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), anti-hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb), hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA, fourth-generation human immunodeficiency virus screening assay, and Epstein-barr virus viral capsid antigen IgM (EBV VCA IgM). In addition, we excluded other potential causes of acute hepatitis (drug-induced liver injury, hereditary hemochromatosis, and Wilson’s disease). Cytomegalovirus IgM (CMV IgM) was positive by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (2.06); however, CMV IgG and pp65-antigenemia (by immunofluorescent assay of peripheral blood leukocytes) were negative. Immunoelectrophoresis revealed increased polyclonal immunoglobulins. The following types of human leukocyte antigen were detected: A24, B7, B71, DR1 and DR4.

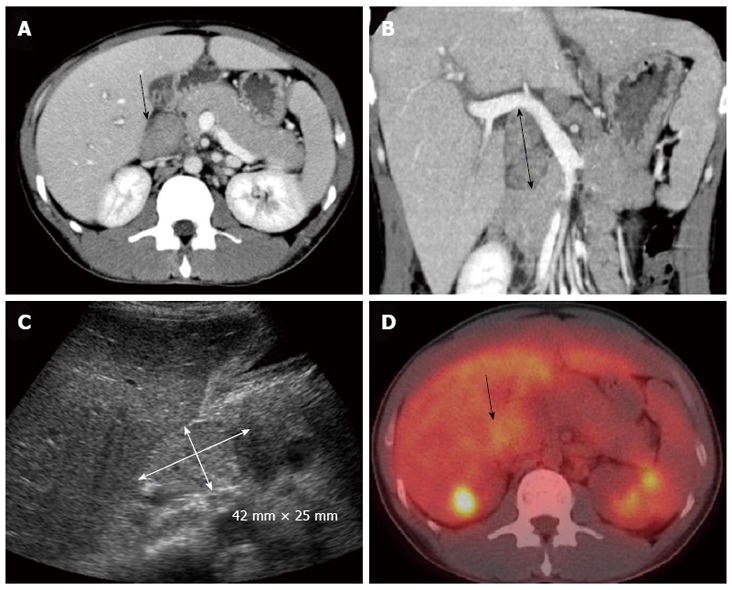

Ultrasonography of the abdomen revealed slightly heterogeneous liver parenchyma and hypoechoic masses around the main trunk of the portal vein. Dynamic computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed an enlarged liver and markedly enlarged HLLNs (50 mm in length along the major axis). Periportal edema, hepatomegaly and thickening of the gallbladder wall were apparent, thereby suggesting acute hepatitis. These lymph nodes displayed high intensity in diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed no dilation of the biliary tract. The positron emission tomography (PET)/CT using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) revealed mild uptake of 18F-FDG in these lymph nodes. The maximum standardized uptake value was determined as 3.98 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Imaging findings. A: Dynamic computed tomographic image (CT) of a transverse section; B: A coronal section revealing enlargement of the hepatoduodenal ligament lymph nodes (arrows); C: Ultrasonography of the abdomen revealing a large mass in the region of the hepatic portal vein (arrow); D: Positron emission tomography/CT using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose revealing mild accumulation. The maximum standardized uptake value was 3.98. The arrow shows the hepatoduodenal ligament lymph nodes.

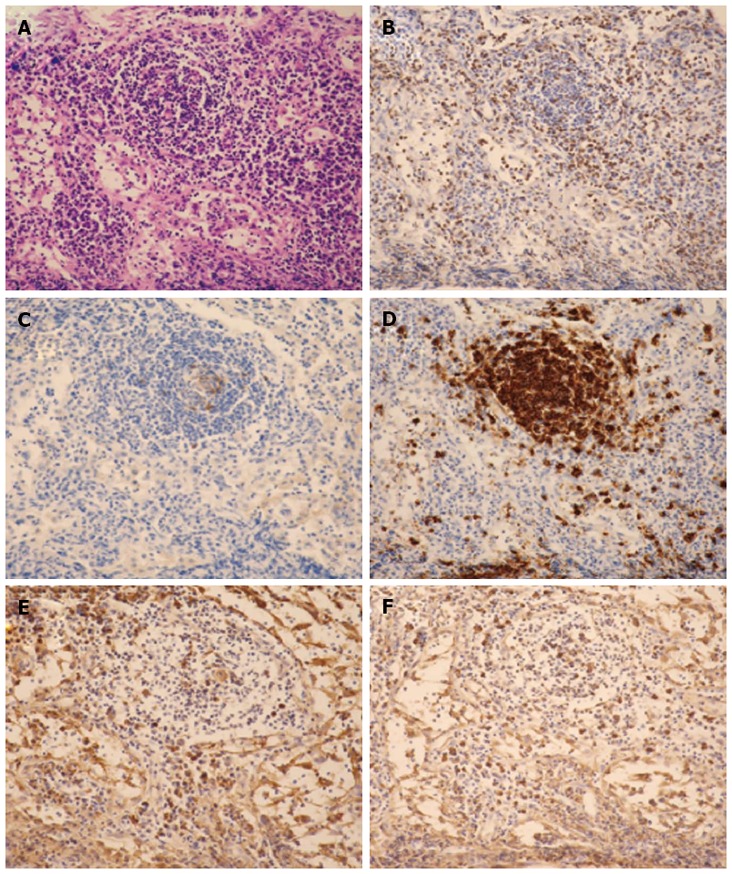

A high titer of ANA and high serum levels of IgG suggested the diagnosis of AIH; however, high serum levels of sIL-2R and markedly enlarged HLLNs prompted us to exclude the possibility of lymphoma before initiating the treatment. Biopsy of the liver and HLLNs were simultaneously performed. Liver biopsy revealed interface hepatitis and lymphocytic infiltration (plasma cell-dominant) without the formation of bridging fibrosis. Lymph node biopsy revealed lymphoid follicles with plasma cell infiltration; however, monoclonal proliferation of malignant cells was not observed by immunohistochemical staining. These observations confirmed the diagnosis of inflamed lymph nodes (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Liver biopsy. A: Liver biopsy specimen with hematoxylin and eosin staining (× 100 magnification) revealing the histopathological appearance of acute hepatitis. Interface hepatitis and plasmacytic infiltrates are present; B: This is the same image at × 400 magnification. P: Portal area; C: Central vein area.

Figure 3.

Histological sections of hepatoduodenal ligament lymph nodes (× 200 magnification). A: The lymphoid follicles contain a reactive germinal center with hematoxylin and eosin staining. No evidences of granuloma or necrosis are visible; B: CD3 (T-cell marker) is positive in the interfollicular areas; C: CD10 (a marker of B-cell activation) is positive in the center of the follicles; D: CD20 (B-cell marker) is observed in the nodules; E: Kappa chain; F: Lambda chain. Neither the kappa nor the lambda chains predominate.

As per the international diagnostic criteria for AIH, our patient’s score was 15[7]. Using the simplified criteria for the diagnosis of AIH, the score was 8[8]. These data were compatible with the final diagnosis of AIH. Moreover, the patient had a hyperbilirubinemia and a mildly reduced PT; thus, we had to consider the potential for severe acute hepatitis or fulminant hepatitis[9]. Corticosteroid pulse therapy with 1000 mg of methylprednisolone for 3 d was started followed by daily administration of 40 mg of prednisolone (per orally) with a dose reduction of 10 mg/d each week. Levels of AST, ALT and T-Bil improved gradually (Figure 4). At the time of discharge, the dose was 20 mg/d, thereafter the dose was reduced by 5 mg/d every 2 wk; subsequently, the levels of AST, ALT, T-Bil, and PT-INR improved. After 2 mo, the enlarged liver reached an almost normal size, and the markedly enlarged HLLNs reduced in size as well (Figure 5). Now, the levels of AST and ALT remain in the normal ranges with 5 mg/d of prednisolone after 8 mo and the size of HLLNs also presents normal size.

Figure 4.

Clinical course. The patients showed high levels of alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin. However, after the initial corticosteroid therapy, these levels improved gradually. ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; T-Bil: Total bilirubin.

Figure 5.

Computed tomography of the transverse section recorded 2 mo after starting corticosteroid. The hepatoduodenal ligament lymph nodes reduced in size.

DISCUSSION

Here we present a case of AIH with markedly enlarged HLLNs (50 mm in diameter). Liver biopsy revealed the features of acute phase AIH; lymph node biopsy revealed lymphoid follicles with inflammatory lymphocytic infiltration (plasma cell-dominant). He was successfully treated with oral prednisolone therapy. After 2 mo, the enlarged lymph nodes reduced in size and the serum AST and ALT levels lowered to normal ranges. In this case, a high serum titer of ANA and elevated IgG levels led us to a diagnosis of AIH. However, elevated serum levels of sIL-2R, markedly enlarged HLLNs, and accumulation of 18F-FDG required us to exclude malignant lymphoma or Castleman’s disease (CD).

A lymphoma in the abdominal cavity is not rare[10]; however, some cases of hepatic lymphoma (e.g., lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma) have been reported to present as a diffuse infiltration of the liver parenchyma without forming a discrete mass[11]. Although the imaging findings of lymphoma vary appreciably in each case[12,13], 18F-FDG PET/CT has become widely used in the diagnosis of malignant lymphomas. However, only 67% of marginal zone lymphomas and 40% of peripheral T-cell lymphomas can take up FDG[14]. The blood chemistry reports and markedly enlarged HLLNs with weakly positive 18F-FDG PET indicated that a malignant lymphoma could not be excluded until biopsy.

CD (also known as angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia) is a rare non-neoplastic lymphoproliferative disorder of unknown etiology[15]. Two clinical presentations can be distinguished. The localized (unicentric) variant of CD is the most common form of the disease and is confined to a single lymph node chain or area; histologically, it is usually a hyaline vascular form and is often asymptomatic and curable by surgical excision. The systemic (multicentric) variant of CD is less common and more aggressive; its corresponding histological pattern is a plasma cell variant and rarely the plasmablastic type[16]. Extremely high levels of interleukin (IL)-6[17] could be a characteristic of the multicentric variant of CD but not of IgG4-related systemic disease or other diseases presenting with lymphadenopathy[18]. CD is usually localized to the chest (especially in the mediastinum and neck) and rarely occurs in the abdominal cavity[19]. A differential diagnosis was necessary between AIH and the unicentric variant of CD. However, in this case, high serum levels of liver transaminases, lymph node findings, and slightly increasing levels of IL-6[17] did not correspond to the unicentric variant of CD. Another differential diagnosis was IgG4-related disease but serum levels of IgG4 were substantially low.

A high incidence of swelling of the intra-abdominal lymph nodes has been reported in patients with non-malignant tumors, particularly subjects with chronic hepatitis B (CHB), chronic hepatitis C (CHC) or primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC)[20]. Swelling of the lymph nodes near the common hepatic artery has been observed in 77%-91% of patients with CHC and 96% of patients with CHB. In addition, a higher incidence of lymph node swelling in PBC (74%-100%) and AIH (13%-73%) has been reported[21]. Furthermore, some studies have reported that lymph node size can be correlated with an index of hepatocellular injury[22,23]. However, the correlation between lymph node size and laboratory data is controversial[24]. We could not find cases of AIH with such enlarged lymph nodes in the literature review similar to the ones described in our case. The pathological significance of enlarged lymph nodes in liver disease is unknown; however, further studies of such cases might help in clarifying its significance.

sIL-2R is an extracellular domain of a membrane-bound IL-2 receptor that is detectable on the cell surface of lymphoid cell lines such as activated T cells and natural killer cells, monocytes, eosinophils[25-27]; and on the cell surface of some tumor cells[28] as well. The biological function of sIL-2R is incompletely understood; however, it is thought to be a marker of T-cell activation[28]. Some studies have demonstrated that sIL-2R levels are increased in liver diseases[29]. Liver damage in AIH is triggered by CD4+ T lymphocytes that recognize a certain autoantigenic epitope on the hepatocytes[30,31]. An activated immune system is deeply involved in the pathophysiology of AIH; thus, highly elevated serum levels of sIL-2R could reflect the inflammatory activity of AIH, as observed in our patient.

In summary, we reported a case of AIH with elevated serum levels of sIL-2R and markedly enlarged HLLNs. Cases with such enlarged lymph nodes (50 mm in diameter) in AIH were not found in our literature review. We speculate that markedly enlarged lymph nodes might reflect a highly activated, humoral immune response in AIH, as observed in our patient.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer Foreman AL S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Czaja AJ, Manns MP. Advances in the diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:58–72.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, Krawitt EL, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Vierling JM. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2193–2213. doi: 10.1002/hep.23584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kogan J, Safadi R, Ashur Y, Shouval D, Ilan Y. Prognosis of symptomatic versus asymptomatic autoimmune hepatitis: a study of 68 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:75–81. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200207000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feld JJ, Dinh H, Arenovich T, Marcus VA, Wanless IR, Heathcote EJ. Autoimmune hepatitis: effect of symptoms and cirrhosis on natural history and outcome. Hepatology. 2005;42:53–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.20732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler WR, Cummings OW, Eckert G, Chalasani N, Lumeng L, Kwo PY. Fulminant hepatic failure as the initial presentation of acute autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:625–631. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Terada R, Onishi T, Okamoto R, Sakai N, Sakaguchi K, Shiratori Y. Clinical characteristics of fulminant-type autoimmune hepatitis: an analysis of eleven cases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1347–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929–938. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Boberg KM, Hofer H, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169–176. doi: 10.1002/hep.22322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abe M, Onji M, Kawai-Ninomiya K, Michitaka K, Matsuura B, Hiasa Y, Horiike N. Clinicopathologic features of the severe form of acute type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:255–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu RS, Zhang WM, Liu YQ. CT diagnosis of 52 patients with lymphoma in abdominal lymph nodes. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7869–7873. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i48.7869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castroagudin JF, Gonzalez-Quintela A, Fraga M, Forteza J, Barrio E. Presentation of T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma mimicking acute hepatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1710–1713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foschi FG, Dall'Aglio AC, Marano G, Lanzi A, Savini P, Piscaglia F, Serra C, Cursaro C, Bernardi M, Andreone P, et al. Role of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in primary hepatic lymphoma. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:1353–1356. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.9.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaneko K, Nishie A, Arima F, Yoshida T, Ono K, Omagari J, Honda H. A case of diffuse-type primary hepatic lymphoma mimicking diffuse hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Nucl Med. 2011;25:303–307. doi: 10.1007/s12149-010-0460-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seam P, Juweid ME, Cheson BD. The role of FDG-PET scans in patients with lymphoma. Blood. 2007;110:3507–3516. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-097238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castleman B, Towne VW. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital; weekly clinicopathological exercises; founded by Richard C. Cabot. N Engl J Med. 1954;251:396–400. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195409022511008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Osta HE, Kurzrock R. Castleman's disease: from basic mechanisms to molecular therapeutics. Oncologist. 2011;16:497–511. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishimoto N, Terao K, Mima T, Nakahara H, Takagi N, Kakehi T. Mechanisms and pathologic significances in increase in serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) and soluble IL-6 receptor after administration of an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Castleman disease. Blood. 2008;112:3959–3964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato Y, Kojima M, Takata K, Morito T, Mizobuchi K, Tanaka T, Inoue D, Shiomi H, Iwao H, Yoshino T. Multicentric Castleman's disease with abundant IgG4-positive cells: a clinical and pathological analysis of six cases. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:1084–1089. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.082958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greco LG, Tedeschi M, Stasolla S, Gentile A, Gentile A, Piscitelli D. Abdominal nodal localization of Castleman's disease: report of a case. Int J Surg. 2010;8:620–622. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakanishi S, Shiraki K, Sugimoto K, Tameda M, Yamamoto K, Masuda C, Iwata M, Koyama M. Clinical significance of ultrasonographic imaging of the common hepatic arterial lymph node (No. 8 LN) in chronic liver diseases. Mol Med Rep. 2010;3:679–683. doi: 10.3892/mmr_00000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.del Olmo JA, Esteban JM, Maldonado L, Rodríguez F, Escudero A, Serra MA, Rodrigo JM. Clinical significance of abdominal lymphadenopathy in chronic liver disease. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28:297–301. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyttkens K, Prytz H, Forsberg L, Hägerstrand I. Hepatic lymph nodes as follow-up factor in primary biliary cirrhosis. An ultrasound study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:1036–1040. doi: 10.3109/00365529509096350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller P, Renou C, Harafa A, Jouve E, Kaplanski G, Ville E, Bertrand JJ, Masson C, Benderitter T, Halfon P. Lymph node enlargement within the hepatoduodenal ligament in patients with chronic hepatitis C reflects the immunological cellular response of the host. J Hepatol. 2003;39:807–813. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00357-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dietrich CF, Lee JH, Herrmann G, Teuber G, Roth WK, Caspary WF, Zeuzem S. Enlargement of perihepatic lymph nodes in relation to liver histology and viremia in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1997;26:467–472. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holter W, Goldman CK, Casabo L, Nelson DL, Greene WC, Waldmann TA. Expression of functional IL 2 receptors by lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma stimulated human monocytes. J Immunol. 1987;138:2917–2922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rand TH, Silberstein DS, Kornfeld H, Weller PF. Human eosinophils express functional interleukin 2 receptors. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:825–832. doi: 10.1172/JCI115383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waldmann TA, Goldman CK, Robb RJ, Depper JM, Leonard WJ, Sharrow SO, Bongiovanni KF, Korsmeyer SJ, Greene WC. Expression of interleukin 2 receptors on activated human B cells. J Exp Med. 1984;160:1450–1466. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.5.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witkowska AM. On the role of sIL-2R measurements in rheumatoid arthritis and cancers. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:121–130. doi: 10.1155/MI.2005.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seidler S, Zimmermann HW, Weiskirchen R, Trautwein C, Tacke F. Elevated circulating soluble interleukin-2 receptor in patients with chronic liver diseases is associated with non-classical monocytes. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Aetiopathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3306–3312. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferri S, Longhi MS, De Molo C, Lalanne C, Muratori P, Granito A, Hussain MJ, Ma Y, Lenzi M, Mieli-Vergani G, et al. A multifaceted imbalance of T cells with regulatory function characterizes type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;52:999–1007. doi: 10.1002/hep.23792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]