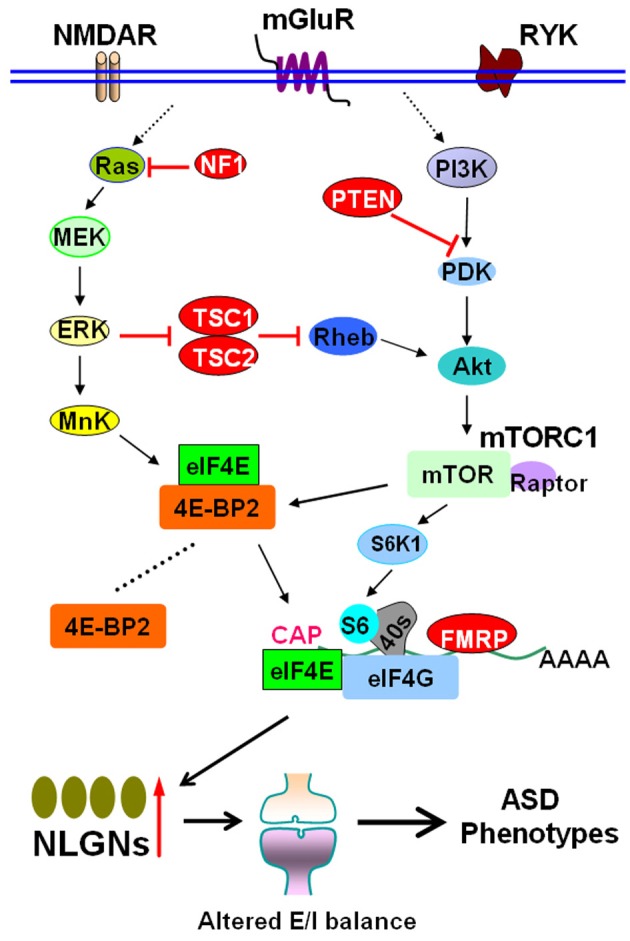

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are a group of clinically and genetically heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by impaired social interactions, repetitive behaviors and restricted interests (Baird et al., 2006; Zoghbi and Bear, 2012). The genetic defects in ASDs may interfere with synaptic protein synthesis. Synaptic dysfunction caused by aberrant protein synthesis is a key pathogenic mechanism for ASDs (Kelleher and Bear, 2008; Richter and Klann, 2009; Ebert and Greenberg, 2013). Understanding the details about aberrant synaptic protein synthesis is important to formulate potential treatment for ASDs. The mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) pathway plays central roles in synaptic protein synthesis (Hay and Sonenberg, 2004; Hoeffer and Klann, 2010; Hershey et al., 2012). Recently, Gkogkas and colleagues published exciting data on the role of downstream mTOR pathway in autism (Gkogkas et al., 2013) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The mTOR signal pathway in autism spectrum disorders. The mTOR pathway integrates inputs from different sources, such as NMDAR, mGluR, and RYK. Activation of mTORC1 promotes the formation of the eIF4F initiation complex. Mutations in TSC1/2, NF1, and PTEN, or loss of FMRP due to mutations of the FMR1gene, cause hyperactivity of mTORC1–eIF4E pathway and lead to syndromic ASDs. 4E-BP2 inhibits translation by competing with eIF4G for eIF4E binding. Gkogkas et al. demonstrated that removal of 4E-BP2 or overexpression of eIF4E enhances cap-dependent translation. The increased translation of NLGNs causes increased synaptic E/I ratio, which may eventually lead to ASD phenotypes. Abbreviations: Akt, also known as PKB, protein kinase B; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; 4E-BP2, eIF4E-binding protein 2; E/I, excitation/inhibiton; ERK, extracellular signal regulated kinase; FMRP, fragile X mental retardation protein; MEK, mitogen-activated protein/ERK kinase; mGluR, metabotropic glutamate receptor; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; mTORC1, mTOR complex 1; NF1, neurofibromatosis 1; NLGN, neuroligin; NMDAR, NMDA receptor; PDK, phosphoinositide dependent kinase; PI3K, phosphoinositide-3 kinase; PTEN, Phosphatase and tensin homolog; Raptor, regulatory associated protein of mTOR; Rheb, Ras homolog enriched in brain; RYK, receptor-like tyrosine kinase; S6K1, p70 ribosomal S6 kinase 1; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex.

Previous studies have indicated that upstream mTOR signaling is linked to ASDs. Mutations in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) 1/TSC2, neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1), and Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) lead to syndromic ASD with tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, or macrocephaly, respectively (Kelleher and Bear, 2008; Bourgeron, 2009; Hoeffer and Klann, 2010; Sawicka and Zukin, 2012). TSC1/TSC2, NF1, and PTEN act as negative regulators of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), which is activated by phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) pathway (Kelleher and Bear, 2008; Auerbach et al., 2011; Sawicka and Zukin, 2012) (Figure 1). Activation of cap-dependent translation is a principal downstream mechanism of mTORC1. The eIF4E recognizes the 5′ mRNA cap, recruits eIF4G and the small ribosomal subunit (Richter and Sonenberg, 2005; Hershey et al., 2012). The eIF4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs) bind to eIF4E and inhibit translation initiation. Phosphorylation of 4E-BPs by mTORC1 promotes eIF4E release and initiates cap-dependent translation (Richter and Klann, 2009; Hoeffer and Klann, 2010) (Figure 1). A hyperactivated mTORC1–eIF4E pathway is linked to impaired synaptic plasticity in fragile X syndrome, an autistic disorder caused by lack of fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) due to mutation of the FMR1 gene (Wang et al., 2010; Auerbach et al., 2011; Santoro et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012), suggesting that downstream mTOR signaling might be causally linked to ASDs. Notably, one pioneering study has identified a mutation in the EIF4E promoter in autism families (Neves-Pereira et al., 2009), implying that deregulation of downstream mTOR signaling (eIF4E) could be a novel mechanism for ASDs.

As an eIF4E repressor downstream of mTOR, 4E-BP2 has important roles in synaptic plasticity, learning and memory (Banko et al., 2005; Richter and Klann, 2009). Writing in their Nature article, Gkogkas and colleagues reported that deletion of the gene encoding 4E-BP2 (Eif4ebp2) leads to autistic-like behaviors in mice. Pharmacological inhibition of eIF4E rectifies social behavior deficits in Eif4ebp2 knockout mice (Gkogkas et al., 2013). Their study in mouse models has provided direct evidence for the causal link between dysregulated eIF4E and the development of ASDs.

Are these ASD-like phenotypes of the Eif4ebp2 knockout mice caused by altered translation of a subset mRNAs due to the release of eIF4E? To test this, Gkogkas et al. measured translation initiation rates and protein levels of candidate genes known to be associated with ASDs in hippocampi from Eif4ebp2 knockout and eIF4E-overexpressing mice. They found that the translation of neuroligin (NLGN) mRNAs is enhanced in both lines of transgenic mice. Removal of 4E-BP2 or overexpression of eIF4E increases protein amounts of NLGNs in the hippocampus, whereas mRNA levels are not affected, thus excluding transcriptional effects (Gkogkas et al., 2013). In contrast, the authors did not observe any changes in the translation of mRNAs coding for other synaptic scaffolding proteins. Interestingly, treatment of Eif4ebp2 knockout mice with selective eIF4E inhibitor reduces NLGN protein levels to wild-type levels (Gkogkas et al., 2013). These data thus indicate that relief of translational suppression by loss of 4E-BP2 or by the overexpression of eIF4E selectively enhances the NLGN synthesis. However, it cannot be ruled out that other proteins (synaptic or non-synaptic) may be affected and contribute to animal autistic phenotypes.

Aberrant information processing due to altered ratio of synaptic excitation to inhibition (E/I) may contribute to ASDs (Rubenstein and Merzenich, 2003; Bourgeron, 2007; Uhlhaas and Singer, 2012). The increased or decreased E/I ratio has been observed in ASD animal models (Chao et al., 2010; Bateup et al., 2011; Luikart et al., 2011; Schmeisser et al., 2012). In relation to these E/I shifts, Gkogkas et al then examined the synaptic transmission in hippocampal slices of Eif4ebp2 knockout mice. They found that 4E-BP2 de-repression results in an increased E/I ratio, which can be explained by the increase of vesicular glutamate transporter and spine density in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. As expected, application of eIF4E inhibitor restores the E/I balance (Gkogkas et al., 2013).

Finally, in view of the facts that genetic manipulation of NLGNs results in ASD-like phenotypes with altered E/I balance in mouse models (Chubykin et al., 2007; Tabuchi et al., 2007; Etherton et al., 2011) and NLGN mRNA translation is enhanced concomitant with increased E/I ratio in Eif4ebp2 knockout mice, Gkogkas et al. tested the effect of NLGN knockdown on synaptic plasticity and behaviour in these mice (Gkogkas et al., 2013). NLGN1 is predominantly postsynaptic at excitatory synapses and promotes excitatory synaptic transmission (Varoqueaux et al., 2006; Kwon et al., 2012). The authors found that NLGN1 knockdown reverses changes at excitatory synapses and partially rescues the social interaction deficits in Eif4ebp2 knockout mice (Gkogkas et al., 2013). These findings thus established a strong link between eIF4E-dependent translational control of NLGNs, E/I balance and the development of ASD-like animal behaviors (Figure 1).

In summary, Gkogkas et al. have provided a model for mTORC1/eIF4E-dependent autism-like phenotypes due to dysregulated translational control (Gkogkas et al., 2013). This novel regulatory mechanism will prompt investigation of downstream mTOR signaling in ASDs, as well as expand our knowledge of how mTOR functions in human learning and cognition. It may narrow down therapeutic targets for autism since targeting downstream mTOR signaling reverses autism. Pharmacological manipulation of downstream effectors of mTOR (eIF4E, 4E-BP2, and NLGNs) may eventually provide therapeutic benefits for patients with ASDs.

Acknowledgments

Hansen Wang was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No.30200152) for Rett syndrome studies and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Fragile X Research Foundation of Canada. Laurie Doering was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and the Fragile X Research Foundation of Canada.

References

- Auerbach B. D., Osterweil E. K., Bear M. F. (2011). Mutations causing syndromic autism define an axis of synaptic pathophysiology. Nature 480, 63–68 10.1038/nature10658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird G., Simonoff E., Pickles A., Chandler S., Loucas T., Meldrum D., et al. (2006). Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Lancet 368, 210–215 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69041-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banko J. L., Poulin F., Hou L., DeMaria C. T., Sonenberg N., Klann E. (2005). The translation repressor 4E-BP2 is critical for eIF4F complex formation, synaptic plasticity, and memory in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 25, 9581–9590 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2423-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateup H. S., Takasaki K. T., Saulnier J. L., Denefrio C. L., Sabatini B. L. (2011). Loss of Tsc1 in vivo impairs hippocampal mGluR-LTD and increases excitatory synaptic function. J. Neurosci. 31, 8862–8869 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1617-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeron T. (2007). The possible interplay of synaptic and clock genes in autism spectrum disorders. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 72, 645–654 10.1101/sqb.2007.72.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeron T. (2009). A synaptic trek to autism. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 19, 231–234 10.1016/j.conb.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao H. T., Chen H., Samaco R. C., Xue M., Chahrour M., Yoo J., et al. (2010). Dysfunction in GABA signalling mediates autism-like stereotypies and Rett syndrome phenotypes. Nature 468, 263–269 10.1038/nature09582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubykin A. A., Atasoy D., Etherton M. R., Brose N., Kavalali E. T., Gibson J. R., et al. (2007). Activity-dependent validation of excitatory versus inhibitory synapses by neuroligin-1 versus neuroligin-2. Neuron 54, 919–931 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D. H., Greenberg M. E. (2013). Activity-dependent neuronal signalling and autism spectrum disorder. Nature 493, 327–337 10.1038/nature11860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etherton M., Foldy C., Sharma M., Tabuchi K., Liu X., Shamloo M., et al. (2011). Autism-linked neuroligin-3 R451C mutation differentially alters hippocampal and cortical synaptic function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 13764–13769 10.1073/pnas.1111093108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkogkas C. G., Khoutorsky A., Ran I., Rampakakis E., Nevarko T., Weatherill D. B., et al. (2013). Autism-related deficits via dysregulated eIF4E-dependent translational control. Nature 493, 371–377 10.1038/nature11628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay N., Sonenberg N. (2004). Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 18, 1926–1945 10.1101/gad.1212704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey J. W., Sonenberg N., Mathews M. B. (2012). Principles of translational control: an overview. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4 pii: a011528 10.1101/cshperspect.a011528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffer C. A., Klann E. (2010). mTOR signaling: at the crossroads of plasticity, memory and disease. Trends Neurosci. 33, 67–75 10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher R. J., 3rd, Bear M. F. (2008). The autistic neuron: troubled translation? Cell 135, 401–406 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H. B., Kozorovitskiy Y., Oh W. J., Peixoto R. T., Akhtar N., Saulnier J. L., et al. (2012). Neuroligin-1-dependent competition regulates cortical synaptogenesis and synapse number. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1667–1674 10.1038/nn.3256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luikart B. W., Schnell E., Washburn E. K., Bensen A. L., Tovar K. R., Westbrook G. L. (2011). Pten knockdown in vivo increases excitatory drive onto dentate granule cells. J. Neurosci. 31, 4345–4354 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0061-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves-Pereira M., Muller B., Massie D., Williams J. H., O'Brien P. C., Hughes A., et al. (2009). Deregulation of EIF4E: a novel mechanism for autism. J. Med. Genet. 46, 759–765 10.1136/jmg.2009.066852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter J. D., Klann E. (2009). Making synaptic plasticity and memory last: mechanisms of translational regulation. Genes Dev. 23, 1–11 10.1101/gad.1735809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter J. D., Sonenberg N. (2005). Regulation of cap-dependent translation by eIF4E inhibitory proteins. Nature 433, 477–480 10.1038/nature03205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein J. L., Merzenich M. M. (2003). Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav. 2, 255–267 10.1034/j.1601-183X.2003.00037.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro M. R., Bray S. M., Warren S. T. (2012). Molecular mechanisms of fragile X syndrome: a twenty-year perspective. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 7, 219–245 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicka K., Zukin R. S. (2012). Dysregulation of mTOR signaling in neuropsychiatric disorders: therapeutic implications. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 305–306 10.1038/npp.2011.210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeisser M. J., Ey E., Wegener S., Bockmann J., Stempel A. V., Kuebler A., et al. (2012). Autistic-like behaviours and hyperactivity in mice lacking ProSAP1/Shank2. Nature 486, 256–260 10.1038/nature11015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi K., Blundell J., Etherton M. R., Hammer R. E., Liu X., Powell C. M., et al. (2007). A neuroligin-3 mutation implicated in autism increases inhibitory synaptic transmission in mice. Science 318, 71–76 10.1126/science.1146221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas P. J., Singer W. (2012). Neuronal dynamics and neuropsychiatric disorders: toward a translational paradigm for dysfunctional large-scale networks. Neuron 75, 963–980 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoqueaux F., Aramuni G., Rawson R. L., Mohrmann R., Missler M., Gottmann K., et al. (2006). Neuroligins determine synapse maturation and function. Neuron 51, 741–754 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Bray S. M., Warren S. T. (2012). New perspectives on the biology of fragile X syndrome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 22, 256–263 10.1016/j.gde.2012.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Kim S. S., Zhuo M. (2010). Roles of fragile X mental retardation protein in dopaminergic stimulation-induced synapse-associated protein synthesis and subsequent alpha-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA) receptor internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 21888–21901 10.1074/jbc.M110.116293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoghbi H. Y., Bear M. F. (2012). Synaptic dysfunction in neurodevelopmental disorders associated with autism and intellectual disabilities. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4 pii: a009886 10.1101/cshperspect.a009886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]