|

Nico Westerhof is emeritus professor of physiology. He received an MS degree from Utrecht University, and a Ph.D degree from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Pa. He became associate professor of physiology at VU university, Amsterdam and became full professor in 1980. From 1992 to 2002 he was Scientific Director of the Institute for CArdiovascular Research of VU University (ICaR-VU). In 1996 he received an honorary doctorate from Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland. In 2009 he was recipient of the ‘Oeuvre-prize’ of the Netherlands Society of Physiology and in 2011 received the ‘life time achievement award’ of Artery. His research interest is the cardiovascular system in general, with, at present emphasis on pulmonary hypertension. Berend E Westerhof received a master's degree in Electrotechnical Engineering from the Delft University of Technology and a Ph.D. from the University of Amsterdam in Medical Physics. Berend Westerhof was one of the founders of BMEYE, now Edwards Lifesciences BMEYE, and is involved in clinical studies and multicenter trials. His focus is on noninvasive hemodynamic monitoring and arterial pressure and flow and their relations in the systemic circulation. Berend Westerhof is adjunct researcher in the Laboratory for Clinical Cardiovascular Physiology, AMC Heart Failure Research Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

The heart pumps into the arterial load, a system of elastic tubes. The pump is of pulsatile character and produces pulsatile pressure (P) and flow (F) waves. When we consider pressure and flow only at the entrance of the arterial tree, we have two ways to analyse the system. The first of these is input impedance, a comprehensive but complex description requiring Fourier analysis (Westerhof et al. 2010). The second is the use of models, most notably the Windkessel model, originally proposed by Otto Frank and later extended (Westerhof et al. 2009). However, these overall descriptions do not give information on detailed arterial function. For instance, impedance and Windkessel cannot inform us about what happens to pressure and flow waves in the arterial system.

From measurements of pressure and flow at different locations in the arterial system, we learn that both pressure and flow wave shapes depend on the location of measurement, and that they travel with a certain speed. The so-called wave speed (pulse wave velocity, c) is determined by vessel cross-sectional area A, stiffness and blood density (ρ), as formulated in the Newton–Young and Moens–Korteweg equations. These equations allow for estimation of (local) arterial stiffness (Van Bortel et al. 2012) and are often used in hypertension research (McEniery et al. 2005; Hickson et al. 2010).

Waves and their properties

Let us first assume that the arterial system is a single tube (aorta) of great (infinite) length, with constant properties in terms of diameter and stiffness (‘uniform tube model’). In such a large-diameter model of the aorta, blood viscosity can be neglected. The waves set up by the heart travel forward (‘forward waves’). These pressure and flow waves travel with the same velocity (c) and have the same wave shape at all locations (i.e. they are proportional). The ratio of P and F is given by proportionality factor Zc, the characteristic impedance of the tube, with Zc = ρ × c/A. However, the wave shapes of pressure and flow in the arterial system differ strongly from the ones of this tube model.

An approach one step more realistic is that the tube is not infinitely long, but has the length (l) of the aorta, about 40 cm. If the end is closed, or is set equal to total peripheral resistance, reflections occur at that point. An example of making use of reflections is ultrasound echo. If the medium is infinitely large, no echo can be detected. If an organ is encountered with different speed of sound (and different characteristic impedance), reflected waves arise and can be measured. A similar phenomenon occurs at the end of the tube; reflected or ‘backward’ waves arise.

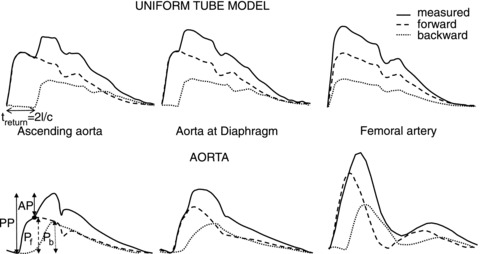

Reflection pertains to pressure and flow in a similar manner with one exception, namely the backward waves of pressure and flow are ‘upside down’ with respect to each other. This may be seen as follows. At the end of the closed tube, the sum of forward and backward pressure makes total pressure twice forward pressure. However, there is no flow, implying that the sum of the forward and backward flow wave is zero, or backward flow is inversed with respect to forward flow. The forward waves arrive at the end after a time delay of c/l, and the backward waves arrive back at the pump after a delay of 2l/c, the so-called return time of the backward wave (Fig. 1). With increasing aortic stiffness, i.e. increasing c, this return time is predicted to decrease. Although this model can be used to explain the basics of wave travel and wave reflection, it is much too simple to be used as model of the arterial system (Taylor, 1957a,b).

Figure 1. Pressure at three locations as predicted by the uniform tube model (top) and as measured (bottom).

The model shows that the forward and backward waves have the same shape at all locations, and the time difference between forward and backward waves decreases with distance from the heart. In the real system, the wave shapes depend on location and the time delay does not decrease with distance. The black dot gives the so-called inflection point, assumed to be equal to the time of return of the backward wave. Abbreviations: AP, augmented pressure; AP/PP, augmentation index; and PP, pulse pressure. The treturn is return time of the reflected wave; l is tube length and c is wave speed. Data are recalculated from earlier studies (left and middle, Murgo et al. 1980, 1981; and right, O’Rourke & Taylor, 1966).

Wave separation

When pressure and flow are known, the forward and backward waves can be derived (Westerhof et al. 1972; Murgo et al. 1981). Even a triangular flow without calibration can be used for the separation (Westerhof et al. 2006). The forward and backward waves derived in this manner are used for analysis of arterial function.

Use of the single tube model of the circulation

Much interpretation of waves is, often unconsciously, based on the single tube model. However, the single tube model is geometrically too simple; it accounts for neither the many branching arteries, nor the local differences in diameter and stiffness of arteries. Based on the tube model, the return time of the backward wave is predicted to depend on length and pulse wave velocity so that aortic stiffness can be derived. This return time prediction is not in agreement with the findings in man (Baksi et al. 2009). Also, the moment of the return time is assumed to be equal to the time of the infection point (Fig. 1, black dot) on the aortic pressure wave. This assumption is inaccurate (Westerhof & Westerhof, 2012). Wang et al. (2011) showed that the time difference between forward and backward waves does not decrease towards the periphery, also underpinning shortcomings of the tube model.

Use of waves to explain changes in the arterial system

Wave reflections occur at all discontinuities, i.e. changes in diameter, branches and changes in stiffness cause reflection; therefore, the single tube with reflection at its end is a poor model of the arterial system (Taylor, 1957a,b). Thus, the predictions given by the single tube model cannot be extrapolated to the real arterial system. Several aspects of forward and backward waves have therefore wrongly been used to gain insight into arterial function, especially its stiffness (see Fig. 1). The augmented pressure is not equal to the backward wave, the inflection point in pressure is wrongly assumed equal to return time of the backward wave and the augmentation index is not equal to reflection magnitude (RM), the amplitude ratio of the backward and forward waves (Westerhof & Westerhof, 2012). These parameters show only weak relations with arterial stiffness (Westerhof & Westerhof, 2012).

We conclude that forward and backward pressure waves in the arterial system do represent reality, but that wave travel and reflection give limited information on arterial function. The uniform tube model with a single reflection site as the basis for interpretation should be abandoned, because reflections occur at many locations.

Call for comments

Readers are invited to give their views on this and the accompanying CrossTalk articles in this issue by submitting a brief comment. Comments may be posted up to 6 weeks after publication of the article, at which point the discussion will close and authors will be invited to submit a ‘final word’.

To submit a comment, go to http://jp.physoc.org/letters/submit/jphysiol;591/5/1167

References

- Baksi AJ, Treibel TA, Davies JE, Hadjiloizou N, Foale RA, Parker KH, Francis DP, Mayet J, Hughes AD. A meta-analysis of the mechanism of blood pressure change with aging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2087–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickson SS, Butlin M, Graves M, Taviani V, Avolio AP, McEniery CM, Wilkinson IB. The relationship of age with regional aortic stiffness and diameter. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:1247–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEniery CM, Yasmin f, Hall IR, Qasem A, Wilkinson IB, Cockcroft JR. Normal vascular aging: differential effects on wave reflection and aortic pulse wave velocity: the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial (ACCT) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1753–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgo JP, Westerhof N, Giolma JP, Altobelli SA. Aortic input impedance in normal man: relationship to pressure wave forms. Circulation. 1980;62:105–116. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.62.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgo JP, Westerhof N, Giolma JP, Altobelli SA. Manipulation of ascending aortic pressure and flow wave reflections with the Valsalva maneuver: relationship to input impedance. Circulation. 1981;63:122–132. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke MF, Taylor MG. Vascular impedance of the femoral bed. Circ Res. 1966;18:126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MG. An approach to an analysis of the arterial pulse wave. I. Oscillations in an attenuating line. Phys Med Biol. 1957a;1:258–269. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/1/3/304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MG. An approach to an analysis of the arterial pulse wave. II. Fluid oscillations in an elastic pipe. Phys Med Biol. 1957b;1:321–329. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/1/4/302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bortel LM, Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Chowienczyk P, Cruickshank JK, De Backer T, Filipovsky J, Huybrechts S, Mattace-Raso FU, Protogerou AD, Schillaci G, Segers P, Vermeersch S, Weber T Artery Society; European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Vascular Structure and Function; European Network for Noninvasive Investigation of Large Arteries. Expert consensus document on the measurement of aortic stiffness in daily practice using carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity. J Hypertens. 2012;30:445–448. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834fa8b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JJ, Shrive NG, Parker KH, Hughes AD, Tyberg JV. Wave propagation and reflection in the canine aorta: analysis using a reservoir-wave approach. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:389–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2010.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof BE, Guelen I, Westerhof N, Karemaker JM, Avolio A. Quantification of wave reflection in the human aorta from pressure alone: a proof of principle. Hypertension. 2006;48:595–601. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000238330.08894.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof BE, Westerhof N. Magnitude and return time of the reflected wave: the effects of large artery stiffness and aortic geometry. J Hypertens. 2012;30:932–939. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283524932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof N, Lankhaar JW, Westerhof BE. The arterial Windkessel. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2009;47:131–141. doi: 10.1007/s11517-008-0359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof N, Sipkema P, van den Bos GC, Elzinga G. Forward and backward waves in the arterial system. Cardiovasc Res. 1972;6:648–656. doi: 10.1093/cvr/6.6.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof N, Stergiopulos N, Noble NIM. Snapshots of Hemodynamics: An Aid for Clinical Research and Graduate Education. 2nd edition. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]