Abstract

The immunological parameters leading to viral persistence in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) are not clearly established. We analyzed HBV-specific immunoregulatory mechanisms in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected HBeAg+ CHB patients to determine (1) the roles of immunoregulatory pathways, (2) the effect of anti-HBV therapy on immunoregulatory pathways, and (3) the role of immunomodulatory therapy to overcome the effect of T regulatory cells (Tregs, CD4+CD25+FoxP3+) in HBV-infected individuals. A prospective, double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial treated HBV (HIV+/–)-infected patients with adefovir 10 mg daily or placebo for 48 weeks. HBV viral load (VL), immunophenotying, and functional studies were performed at multiple time points. Suppression of HBV VL with adefovir leads to decreased peripheral expansion of Tregs. While declining, Tregs significantly inhibit cytokine-secreting HBV-specific CD8+ T cell responses over 48 weeks of anti-HBV adefovir therapy (p<0.05). A large proportion of these Tregs express programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1), blockade of which in vitro leads to improved cytokine-secreting HBV-specific CD8+ T cell responses, particularly in HIV/HBV-coinfected patients (p<0.05). Peripheral expansion of Treg levels correlated with HBV viral load and decreased HBV-specific CD8+ T cells. PD-1 blockade increased survival of HBV-specific CD8+ T cells, removing the inhibitory effect of PD-1+ peripheral Tregs. Hence therapies involving PD-1 blockade in combination with directly acting antivirals should be investigated to reduce the need for life-long directly acting antiviral therapy.

Introduction

Globally, about 350 million people live with chronic hepatitis B (CHB), a leading cause of hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis.1,2 Due to shared routes of transmission, an estimated two to four million CHB patients are coinfected with HIV-1.3,4 While use of highly active antiretroviral therapy has slowed HIV progression, prolonged survival has increased the risk of liver-related mortality in persons coinfected with HIV-1 and hepatitis B virus (HBV).5,6 Furthermore, individuals with HIV-1 exposed to HBV have a greater risk of developing chronicity, a lower rate of spontaneous HBsAg and HBeAg seroconversion, a higher level of HBV DNA, and modest responses to antiviral treatment compared with HIV-uninfected individuals.7,8 Although directly acting nucleoside analogs have been shown to suppress HBV replication in vivo to below the level of detection9 only interferon-α (IFN)-based therapy has been shown to eradicate HBV by boosting host immunity against HBV.10,11 The differential treatment responses observed between immunomodulatory (IFN) and nucleoside analog HBV drugs suggest that an immune-mediated mechanism directed toward HBV is essential for clearance of HBV and development of protective immunity. However, IFN is associated with significant adverse events and poor tolerance.9 Enhancement of HBV-specific immunity using novel immunomodulatory agents offers a promising strategy for eradication of HBV in CHB patients.

Most studies have shown that the peripheral HBV-specific immune response is weak in CHB patients.12,13 Recent studies, however, have shown a higher percentage of T regulatory cells (Treg) in the peripheral blood of CHB patients as compared to uninfected individuals14 and a positive correlation between Treg activity and HBV viral load among HBeAg-negative CHB patients.15 Tregs, demarcated by CD4+CD24+FoxP3+ expression,16 inhibit effective virus-specific immune responses17,18 and can also express programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1), which further deters immune responses when expressed on CD4+, CD8+, NK T cells, monocytes, or B cells.19–23 In this study, we investigated the immunoregulatory mechanisms that suppress HBV-specific immunity in HIV-positive and HIV-negative CHB patients and explored methods to augment the HBV-specific immune response thereby enhancing the potential for HBV eradication.

Materials and Methods

Study design

Patient samples were obtained from two studies, a prospective double blind randomized placebo controlled trial in which HBV/HIV-1-coinfected patients (n=11) were treated with adefovir (n=8) or placebo (n=3) for 48 weeks and a second prospective study in which HBV-monoinfected patients (n=5) received open label adefovir for 48 weeks. Patients receiving adefovir had liver biopsies before and after treatment. All HIV-infected patients were receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) with CD4>100 cells/μl. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from healthy individuals in the Transfusion Medicine Department of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center (negative controls). All patients signed informed consent forms and were enrolled in protocols approved by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Institutional Review Board. Immunophenotyping and functional studies were performed at baseline and after 24 and 48 weeks of treatment. HBL viral load (VL) was measured by real-time PCR at frequent time points.

Isolation of PBMCs and detection of HBV-specific responses

PBMCs were separated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation and washed twice in RPMI-1640 medium. For functional assays, the frequency of cytokine-producing [interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interleukin (IL)-2] CD8+ T cells was determined as described below. PBMCs (2×105 cells/well), in the presence of 1 μg/ml anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody (mAb), were stimulated in triplicate with 2 μg/ml pooled overlapping 15-mer peptides derived from consensus sequences of the HBV genotype A complete genome (Mimotopes, Inc., Australia), HIV-Gag pooled peptides, cytomegalovirus (CMV) peptides (ProSpec), or staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) (positive control). After the first 1 h of incubation, Brefeldin-A (Sigma, USA) was added at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Following a 12-h incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, cells were stained for surface antigens using APC-Cy7-anti-CD3, APC-anti-CD4, and PE-Cy7-anti-CD8, washed, centrifuged, permeabilized, fixed, and then stained with the cytokine-specific antibodies PE-anti-IFN-γ, PE-anti-TNF-α, and PE-anti-IL-2. All samples were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer [containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.05% NaN3] and resuspended in 0.1% paraformaldehyde. Cells were acquired on a Cyan Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar Inc.). The magnitude of patient responses was calculated as the sum of the percentage of CD8+ cytokine-positive T cells for peptide pools.24 Supplementary Fig. S1 (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid) shows the gating strategy for detecting and quantifying HBV-specific CD8+ T cell responses.

Quantitation of Tregs in peripheral blood

To determine the frequency of cells with a Treg phenotype, 2×105 PBMCs/well were plated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were stained for surface markers using APC-Cy7-anti-CD3, APC-anti-CD4, and PE-Cy7-anti-CD8 (BD Biosciences), washed, centrifuged, permeabilized, fixed, and stained with PE-anti-FoxP3 antibody (BD Biosciences). All samples were washed in PBS buffer (containing 0.1% BSA and 0.05% NaN3), resuspended in 0.1% paraformaldehyde, acquired by flow cytometry, and analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar Inc.)

Measurement of the modulatory effects of HBV-specific Tregs

PBMCs were depleted of CD4+ T cells followed by removal of CD4+CD25+ T cells by magnetic labeling per the manufacturer's protocol (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany). To determine the effect of CD4+CD25+ Tregs on virus-specific CD8+ T cells, CD4−CD25− T cells were incubated±CD4+CD25+ at a 1:10 ratio and stimulated with HBV-, HIV-, or CMV-specific peptides at a concentration of 2 μg/ml. The frequency of pooled cytokine-producing CD8+ T cells was measured at baseline and at week 24 and week 48 as described above.

PD-1/PD-L1 blockade and HBV-specific CD8+ T cell immune responses

PBMCs were stimulated with HBV-, HIV-, or CMV-specific peptides at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml with or without PD-1/PD-L1 (BioLegend) or mouse IgG (isotype control) at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. Stimulation of PBMCs with SEB was used as a positive control. Brefeldin-A (Sigma, USA) (10 μg/ml) was added after the first 1 h of incubation. Cytokine-secreting CD8+ T cells were analyzed as previously described. FoxP3 expression was confirmed on Tregs using an anti-FITC-FoxP3 antibody.

Cell surface markers and flow cytometric analysis

The following antibodies were used for PBMC staining: PECy7-anti-CD3, FITC-anti-CD8, APC-anti-CD25, and PE-anti-PD-1 (Biolegend) for 20 min at room temperature and then washed twice with PBS and fixed using 0.1% paraformaldehyde.

A total of 100,000 events were acquired on the Facsarray flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analysis was performed using FlowJo software (DAKO, USA). The percentage expression of each subset was evaluated within the total CD3+ or CD3+CD4+ or CD3+CD8+ T cell population.

Direct immunostaining of liver biopsy tissue for FoxP3 and PD-1-expressing cells

Immunohistochemistry staining for FoxP3 and dual staining for PD-1 and CD3 were performed on human paraffin-embedded liver biopsy tissue before and after 48 weeks of adefovir therapy, as well as on tonsillar tissues (positive control) using PE-conjugated antihuman FoxP3 mAb, anti-PD-1-Ab (J116 clone, ebioscience) with HRP and DAB for color development, or rabbit anti-CD3 (Dako) with polymer AP and fast-red chromogen (Dako) for color development.

Statistical analysis

ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison tests was used to compare means of independent groups. Mean HBV DNA (log10) at baseline and follow-up were analyzed using Student's t-test. R-values were calculated for HBV DNA levels and frequency of CD4+ Tregs at baseline and follow-up using the Pearson correlation coefficient. A paired t-test with the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple tests was used to compare paired responses.

Results

Patient profile

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The blind was broken after data analysis was completed. The mean age was 41 years (range, 17–71 years). Race, mean CD4+ T cell count, and HBV DNA were significantly different between the two groups (χ2=0.04, p=0.02, p=0.0003, respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Patients by HIV Infection Status

| HBV+/HIV− | HBV+/HIV+ | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 5 | 11 |

| Age (median years (IQR) | 40 (30–46) | 38.5 (36.75–47.25) |

| Male (%) | 100% | 100% |

| Race | ||

| Asian (n) | 2 (40%) | 0 |

| AA (n) | 1 (20%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| White (n) | 2 (40%) | 11 (91.7%) |

| CD4+ [median cells/μl (IQR)] | 816 (773, 918) | 303 (163, 576) |

| Plasma HBV DNA [median copies/ml (IQR)] | 1.9×1010 (2.16×107, 3.37×109) | 3.9×108 (5.4×106, 2.7×109) |

| Plasma HIV-1 RNA [median copies/ml (IQR)] | <50 | 1,148 (445, 1,819) |

HBV, hepatitis B virus; IQR, interquartile range; AA, African-American.

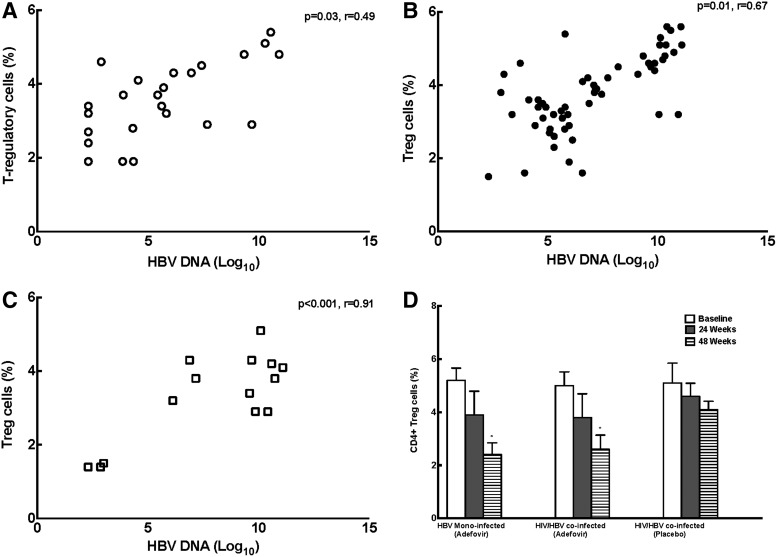

Plasma HBV virus levels correlate with the frequency of Treg cells

We performed immunophenotyping of PBMCs at baseline and after 24 and 48 weeks of treatment. Correlation analysis were performed with various immune markers and HBV DNA. There was a positive correlation between HBV DNA and percentages of cells with a Treg phenotype (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+) in HBV-monoinfected adefovir-treated (Fig. 1A, p=0.03, r=0.49), HIV/HBV adefovir-treated (Fig. 1B, p=0.01, r=0.67), and placebo-treated patients (Fig. 1C, p<0.001, r=0.91). Over 48 weeks a significant reduction in Tregs was observed in HBV-treated (5.2±0.8%, 3.9±2.0%, 2.4±1.0% Tregs at baseline and at 24 and 48 weeks; p=0.01 baseline vs. 48 weeks) and HIV/HBV-treated patients (5.0±0.9%, 3.8±2.0%, 2.6±1.2% Tregs at baseline and at 24 and 48 weeks, p=0.03 baseline vs. 48 weeks). No reduction in Tregs was seen in placebo-treated patients (5.1±1.3%, 4.6±1.1%, 4.1±0.7% Tregs at baseline and at 24 and 48 weeks) (Fig. 1D). One placebo-treated patient who had a decline in Tregs also had a spontaneous decline in HBV VL.

FIG. 1.

Plasma hepatitis B virus (HBV) viral levels correlate with the frequency of cells with Treg phenotype. (A) HIV/HBV adefovir-treated patients. (B) HBV-monoinfected adefovir-treated patients. (C) HIV/HBV-coinfected patients. (D) A significant reduction in Tregs over 48 weeks was observed in HBV-monoinfected adefovir-treated patients and HIV/HBV adefovir-treated patients (*p<0.05). No reduction in Tregs was seen in placebo-treated patients.

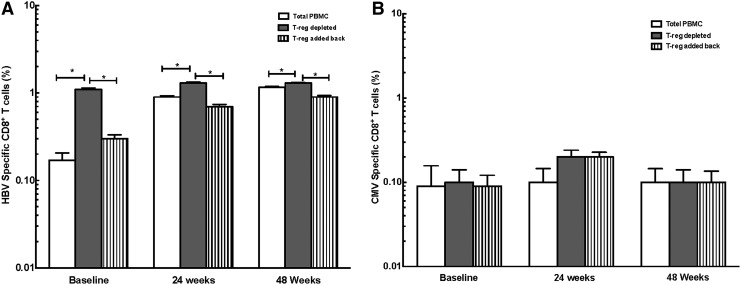

Tregs suppress HBV-specific CD8+ T cell responses at baseline

To determine the effect of Tregs on immune function, we performed experiments to quantitate virus (HBV, HIV, and CMV)-specific or polyclonal (SEB) (positive control) CD8+ T cell responses in vitro in the presence or absence of Tregs. Depletion of Tregs led to an increase in cytokine-secreting HBV-specific CD8+ T cells in both HBV-infected and HIV/HBV-infected patients. Readdition of autologous Tregs decreased HBV-specific cytokine-secreting CD8+ T cells, suggesting that Tregs inhibit HBV-specific responses in both HBV-monoinfected and HIV/HBV-coinfected patients [HBV monoinfected baseline: 0.17±0.08%, 1.10±0.09%, 0.30±0.07% HBV-specific CD8+ T cells in PBMCs, with Treg depletion and readdition, respectively, p<0.0001 PBMCs vs. Treg-depleted and Treg-depleted vs. readdition; 24 weeks: 0.9±0.06%, 1.3±0.09%, 0.30±0.07% HBV-specific CD8+ T cells in PBMCs, with Treg depletion and readdition, respectively, p<0.0001 PBMCs vs. Treg-depleted and Treg-depleted vs. readdition; 48 weeks: 1.16±0.07%, 1.3±0.06%, 0.90±0.08% HBV-specific CD8+ T cells in PBMCs, with Treg depletion and readdition, respectively, p<0.001 PBMCs vs. Treg-depleted and depleted vs. Treg readdition (Fig. 2A); HIV/HBV baseline: 0.14±0.07%, 1.30±0.10%, 0.18±0.09% HBV-specific CD8+ T cells in PBMCs, with Treg depletion and readdition, respectively, p<0.0001 PBMCs vs. Treg-depleted and Treg-depleted vs. readdition; 24 weeks: 0.65±0.09%, 0.9±0.08%, 0.56±0.10% HBV-specific CD8+ T cells in PBMCs, with Treg depletion and readdition, respectively, p<0.0001 PBMCs vs. Treg-depleted and Treg-depleted vs. readdition; 48 weeks: 0.95±0.09%, 1.10±0.1%, 0.80±0.90% HBV-specific CD8+ T cells in PBMCs, with Treg depletion and readdition, respectively, p<0.008 PBMCs vs. Treg-depleted and Treg-depleted vs. readdition (Fig. 3A)]. Our results demonstrate a significant and persistent (48 week) reduction in HBV-specific peripheral CD8+ T cell responses in the presence of expanded Tregs in both HBV-infected and HIV/HBV-infected patients.

FIG. 2.

Tregs suppress HBV-specific CD8+ T cell responses in HBV-infected patients. (A) The depletion and readdition of autologous Tregs significantly increased and then decreased the number of HBV-specific CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from HBV monoinfected adefovir-treated patients at baseline and at 24 and 48 weeks (*p<0.001). (B) No change in CD8+ T cells was seen in response to cytomegalovirus (CMV)-specific peptides.

FIG. 3.

Tregs suppress HBV-specific CD8+ T cell responses in HIV/HBV-infected patients. (A) The depletion and readdition of autologous Tregs significantly increased and then decreased the number of HBV-specific cytokine-secreting CD8+ T cells in PBMCs from HIV/HBV patients at baseline and at 24 and 48 weeks (*p<0.001). (B) No change in CD8+ T cells was seen in response to CMV-specific peptides. (C) The depletion and readdition of autologous Tregs significantly increased and then decreased the number of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells in HIV/HBV patients at baseline and at 24 and 48 weeks (*p<0.0001).

Comparison of HBV and HIV/HBV patients showed significantly higher HBV-specific CD8+ T cells in HBV-monoinfected patients than HIV/HBV-coinfected patients at baseline and at 24 and 48 weeks (p<0.05).

No significant change in CD8+ T cells was seen in response to CMV-specific peptides despite depletion and readdition of Tregs in HBV- (Fig. 2B) and HIV/HBV-infected patients (Fig. 3B).

Similar to HBV-specific responses, HIV-specific CD8+ T cells increased after Treg depletion in HIV/HBV patients at baseline and at 24 and 48 weeks [baseline: 0.6±0.10%, 0.9±0.7%, 0.5±0.5% HIV-specific CD8+ T cells in PBMCs, with Treg depletion and readdition, respectively; p<0.0001 PBMCs vs. Treg-depleted and Treg-depleted vs. readdition; 24 weeks: 0.8±0.13%, 1.1±0.12%, 0.9±0.10% HIV-specific CD8+ T cells in PBMCs, with Treg depletion and Treg readdition, respectively, p<0.0001 PBMCs vs. depleted and depleted vs. readdition, and 48 weeks: 0.9±0.13%, 1.2±0.12%, 0.9±0.18% HIV-specific CD8+ T cells in PBMCs, with Treg depletion and readdition, respectively, p<0.0001 PBMCs vs. Treg-depleted and Treg-depleted vs. readdition (Fig. 3C)]. There was a small, but significant increase in HIV-specific CD8+ T cells in HIV/HBV-coinfected patients after 48 weeks of HBV therapy (p<0.05).

HBV-specific inhibitory Tregs decline with control of HBV replication

HBV-specific immunity as measured by cytokine-secreting HBV-specific CD8+ T cells was enhanced after 48 weeks of adefovir therapy compared to baseline in both HBV-infected and HIV/HBV-infected patients. This difference was statistically significant in HBV-monoinfected patients (p<0.0001). No enhancement was seen in CMV-specific CD8+ T cells, suggesting a reconstitution of only HBV-specific immune response and an overall decrease in the phenotype and function of HBV-specific peripheral Tregs with control of HBV replication.

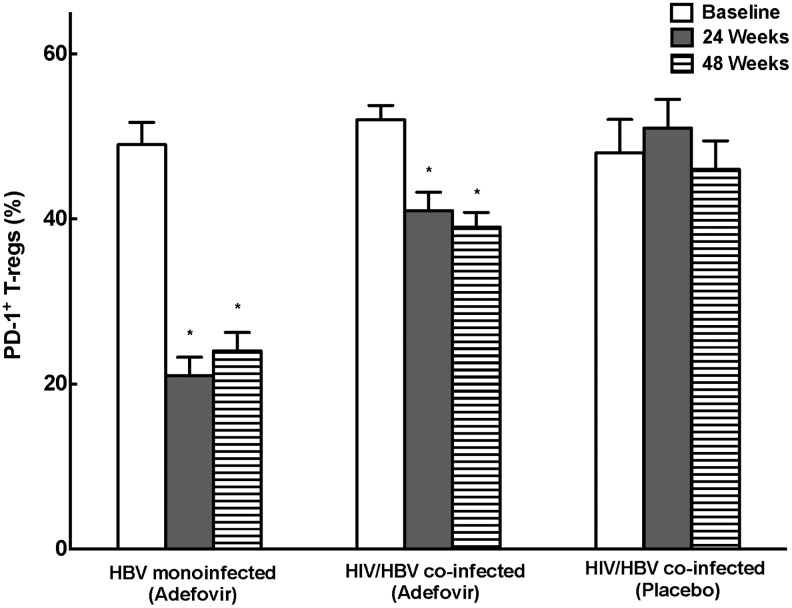

Peripheral Tregs express PD-1

Consistent with the overall decline in peripheral Treg cells with control of HBV replication, the percentage of Tregs expressing PD-1 was high in HBV-infected and HIV/HBV-infected patients at baseline (49±6% HBV, 52±6% HIV/HBV, 48±7% placebo) (Fig. 4A), but decreased significantly after 24 and 48 weeks of adefovir (21±5% and 24±5% HBV and 41±5% and 39±4% HIV/HBV at 24 and 48 weeks, respectively p<0.01). The incomplete suppression of PD-1+ Tregs while on adefovir therapy suggests a potential unique role for these cells in inhibiting HBV-specific immunity.

FIG. 4.

Peripheral Tregs express programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1). The percentage of Tregs expressing PD-1+ was high at baseline, but decreased significantly at 24 and 48 weeks in both HBV- and HIV/HBV-infected patients compared to baseline (*p<0.01).

PD-1 blockade enhances HBV-specific immunity in CHB patients

Although control of HBV replication resulted in improved HBV-specific immunity as measured by increased cytokine-secreting CD8+ T cells at 48 weeks, this did not result in the development of protective immunity, as measured by HBsAg seroconversion (0%) or HBeAg seroconversion (6%). These results suggest that suppression of HBV replication with nucleoside analogs for 48 weeks alone is not enough to boost HBV-specific immunity to eradicate HBV and develop protective immunity. As a strategy to enhance HBV-specific immunity, PBMCs from HIV-positive and HIV-negative CHB patients were treated in vitro with PD-1/PD-L1.

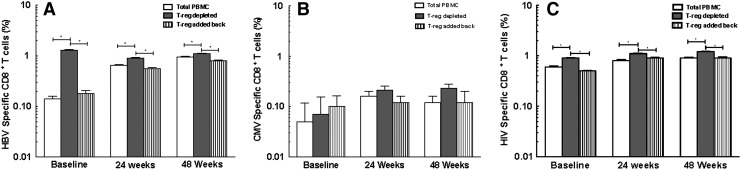

As shown in Figs. 5A and 6A, PD-1 blockade enhanced the frequency of cytokine-secreting HBV-specific CD8+ T cells at baseline more in HIV/HBV-coinfected patients (0.13±0.09% untreated, 0.90±0.10% PD-1/PD-L1 p<0.0001 vs. untreated, respectively) as compared to HBV-monoinfected (0.15±0.10% untreated, 1.6±2% PD-1/PD-L1, p=0.14 vs. untreated) patients.

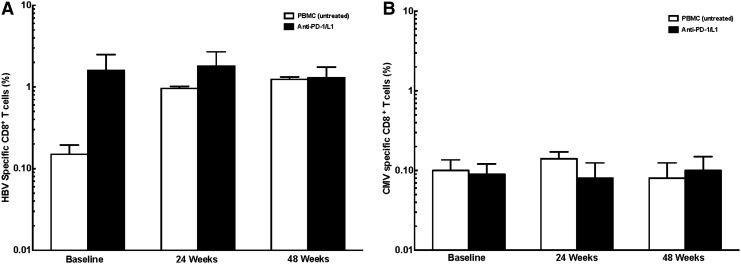

FIG. 5.

HBV-specific immunity after PD-1 blockade in HBV patients. (A) Increased, but not significant, cytokine-secreting HBV-specific CD8+ T cells after PD-1 blockade. (B) No change in cytokine-secreting CMV-specific CD8+ T cells.

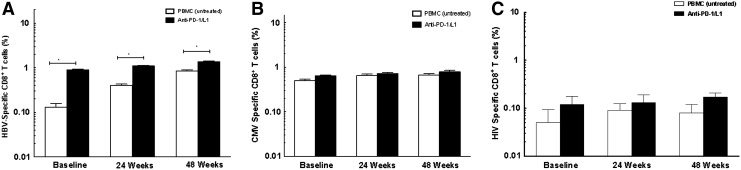

FIG. 6.

PD-1 blockade enhances HBV-specific immunity in HIV/HBV-infected chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients. (A) PD-1 blockade increased cytokine-secreting HBV-specific CD8+ T cells as compared to untreated cells at baseline and at 24 and 48 weeks in HIV/HBV-infected patients (*p<0.001). (B) No change in cytokine-secreting CMV-specific CD8+ T cells. (C) No change in cytokine-secreting HIV-specific CD8+ T cells.

PD-1 blockade similarly enhanced cytokine-secreting HBV-specific CD8+ T cells after 24 and 48 weeks in HBV and HIV/HBV patients. These increases, however, were not as large as those seen as baseline, and were significant only in HIV/HBV-infected patients (HBV: 24 weeks: 0.96±0.13% untreated, 1.8±2% PD-1/PD-L1; 48 weeks: 1.24±0.20% untreated, 1.3±1% PD-1/PD-L1; p>0.05 vs. untreated; HIV/HBV: 24 weeks: 0.40±1.0% untreated; 1.1%±0.09 PD-1/PD-L1, p<0.0001, vs. untreated; 48 weeks: 0.85±0.13% untreated; 1.5±0.4% IL-15, 1.4%±0.15 PD-1/PD-L1; p<0.001 vs. untreated).

PD-1/PD-L1 does not augment HIV or CMV-specific immunity in CHB patients

Addition of PD-1/PD-L1 did not change CMV-specific CD8+ T cells in HBV-infected and HIV/HBV-infected patients [HBV baseline: 0.10±0.08% untreated, 0.90±0.07% PD-1/PD-L1, p>0.05 vs. untreated; 24 weeks: 0.14±0.07% untreated, 0.08±0.10% PD-1/PD-L1, p>0.05 vs. untreated; 48 weeks: 0.08±0.10% untreated, 0.10±0.11% PD-1/PD-L1, p>0.05 vs. untreated, respectively (Fig. 5B); HIV/HBV baseline: 0.05±0.15% untreated, 0.12±0.20% PD-1/PD-L1, p>0.05 vs. untreated; 24 weeks: 0.09±0.12% untreated, 0.13±0.21% PD-1/PD-L1, p>0.05 vs. untreated; 48 weeks: 0.08±0.14% untreated, 0.17±0.13% PD-1/PD-L1 p<0.05 vs. untreated (Fig. 6B)].

In HIV/HBV patients, the addition of PD-1/PD-L1 also does not change HIV-specific CD8+ T cells at baseline (0.50±0.13% untreated, 0.12±0.2% PD-1/PD-L1, p>0.05 vs. untreated), 24 weeks (0.09±0.12% untreated, 0.13±0.21% PD-1/PD-L1, p>0.05 vs. untreated), and 48 weeks (0.08±0.14% untreated, 0.17±0.13% PD-1/PD-L1, p>0.05 vs. untreated) (Fig. 6C).

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that in both HBV and HIV/HBV CHB patients, expansion of HBV-specific peripheral Treg cells correlates with peripheral HBV DNA levels. Control of HBV replication with adefovir was associated with decreased Treg numbers and function. Furthermore, we demonstrated enhanced HBV-specific effector cytotoxic T cells after addition of PD-1 blockade in vitro in HIV/HBV-coinfected patients. Further studies are needed to determine whether the expansion of peripheral Tregs is a direct result of ongoing uncontrolled HBV replication or a bystander effect of the immunological events associated with CHB.

Several studies have reported peripheral expansion of Tregs in HIV-seronegative patients with CHB that correlates with high HBV DNA levels, suggesting an association between HBV replication and induction of Tregs, leading to chronicity in CHB patients.25–27 Treg expansion has also been demonstrated in HIV viremic patients,13 but the relationship between HBV replication and Treg expansion has not been studied in detail in HIV/HBV-coinfected patients. In addition, to our knowledge, no studies have examined a functional role for Tregs in CHB patients before and after control of HBV replication.

In this comprehensive study, we demonstrated that expansion of HBV-specific peripheral Tregs correlates positively with peripheral HBV DNA levels, suggesting that an abundance of Tregs may contribute to the establishment of chronicity by blunting anti-HBV responses.28,29 Second, we demonstrated a specific, suppressive effect of Tregs on HBV-specific cytokine-secreting CD8+ T cells.30 Although other studies have suggested an association between Tregs and HBV viremia,6,31 our findings show that Tregs specifically inhibit HBV-specific immune responses in HIV-negative and HIV-positive CHB patients.

We observed that the frequency of Tregs was significantly reduced with control of HBV replication after 48 weeks of adefovir, and similarly found a significantly higher HBV-specific CD8+ T effector cell response after 48 weeks compared to baseline, suggesting improved HBV immunity. HIV-positive as compared to HIV-negative CHB patients, however, did have a significantly lower HBV-specific CD8+ T effector cell response at 24 and 48 weeks. While other studies have suggested reconstitution of HBV-specific immunity in CHB patients,32,33 our study supports previous literature indicating that this reconstitution is delayed or never complete in HIV-infected CHB patients.24

We also demonstrated that while a decline in HBV DNA levels is accompanied by a reduction in peripheral Treg cells and improved HBV-specific immunity, the CMV- and HIV-specific CD8+ T cell response does not improve as dramatically, similar to other published data.34 The significance of Treg cell reduction in the periphery and enhancement of immunity against HBV antigens is presently not clearly understood.

Although most of our patients had a boost in HBV-specific CD8+ T cells after control of HBV viremia at 48 weeks, this was not associated with the development of long lasting protective immunity (i.e., HBsAg seroconversion). This suggests that control of HBV replication may boost HBV-specific immunity, but complementing this therapy with an immune-based approach, associated with the development of protective immunity and/or the eradication of CHB in infected patients,35 may be necessary to achieve long lasting protective immunity. Immune-based therapies such as IL-15 have been shown to specifically induce cytotoxic CD8+ T effector cells, but these cells can develop an exhaustive, nonfunctional phenotype expressing PD-1.36,37 In our study, a large proportion of peripheral Tregs observed in the periphery of CHB patients also express high levels of PD-1, even after 48 weeks of adefovir and suppression of HBV VL, predisposing them to impaired responsiveness to antigenic stimulation or apoptosis soon after activation.26,27 Additionally, we were able to demonstrate diminished but still high levels of FoxP3+(Supplementary Fig. S2) and PD-1+ Treg cells (Supplementary Fig. S3) in liver biopsy samples after 48 weeks of adefovir treatment compared to baseline (data not shown).

While other studies have examined the role of a PD-1 blockade in regulating Tregs for hepatitis C virus infection, our study demonstrated the effectiveness of PD-1 blockade in HIV/HBV-infected patients.38 Since many effector T cells and Tregs in CHB patients express PD-1, it is unclear whether the enhancement of HBV-specific immunity observed in our patients is due to a direct effect on T cells, T effector memory cells, or both. Regardless of the specific mechanism, our findings show that this strategy is a viable option for treatment of CHB. PD-1 blockade is a therapeutic strategy currently being developed for the treatment for malignancies and other chronic immune disorders.37,39 Our data provide compelling evidence that PD-1 blockade should be investigated in vivo as a viable, adjunct treatment for CHB infection in HIV-positive and potentially HIV-negative patients, especially if the combined effect can eradicate HBV.

The small sample size and short follow-up have limited the ability of our study to some extent. A larger patient population with longer follow-up is needed to determine if diversity of samples (gender, age, race, and HBeAg) has a significant effect on the results. Such a study may show more statistically significant changes in immune responses among coinfected individuals. Although this study clearly showed the association between high viral load and high Treg expression, further studies should be conducted to determine why the correlation exists.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that patients with chronic hepatitis B (HIV+/–) possess high Treg levels, which inhibit anti-HBV immunity. Control of HBV viremia is associated with decreased Treg levels and a boost in HBV-specific immunity. However, eradication of HBV in CHB patients requires a significant increase in HBV-specific effector response, which will likely require an immune-based therapy. PD-1 blockade boosts the HBV-specific CD8+ T cell effector response, particularly in HIV/HBV-coinfected patients, and alone or in combination with other immune-based therapies may result in preferential expansion of long-lived effector memory cells and reduce the need for life long DAT in CHB patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract no. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This research was supported [in part] by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Shi JZL. Liu S. Xie WF. A meta-analysis of case-control studies on the combined effect of hepatitis B and C virus infections in causing hepatocellular carcinoma in China. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:607–612. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Fact Sheet, Hepatitis B: World Health Organization (WHO) Fact Sheets

- 3.WHO: AIDS Epidemic Update

- 4.Alter M. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol. 2006;44(Suppl 1):S6–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bica I. McGovern B. Dhar R, et al. Increasing mortality due to end-stage liver disease in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:492–497. doi: 10.1086/318501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thio CL. Skolasky R., Jr Phair J. Visscher B. Muñoz A. Thomas DL. HIV-1, hepatitis B virus, and risk of liver-related mortality in the Multicenter Cohort Study (MACS) Lancet. 2002;360(9346):1921–1926. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11913-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rector WGS. Horsburgh C. Penley K. Cohn D. Judson F. Hepatic inflammation, hepatitis B replication, and cellular immune function in homosexual males with chronic hepatitis B and antibody to HIV. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:262–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colin J. Loriot M. Influence of HIV infection on chronic hepatitis B in homosexual men. Hepatology. 1999;29:1306–1310. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liaw YF. Sung JJ. Chow WC. Farrell G. Lee CZ. Yuen H. Tanwandee T. Tao QM. Shue K. Keene ON. Dixon JS. Gray DF. Sabbat J. Cirrhosis Asian Lamivudine Multicentre Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521–1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong DK. Cheung AM. O'Rourke K. Naylor CD. Detsky AS. Heathcote J. Effect of alpha-interferon treatment in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(4):312–323. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-4-199308150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akbar F. Yoshida O. Abe M. Hiasa Y. Onji M. Engineering immune therapy against hepatitis B virus. Hepatol Res. 2007;37(Suppl 3):S351–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen M. Zhang D. Zhen W, et al. Characteristics of circulating T cell receptor gamma-delta T cells from individuals chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV): An association between V(delta)2 subtype and chronic HBV infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(11):1643–1650. doi: 10.1086/593065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlaak JF. Tully G. Lohr HF. Gerken G. Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH. HBV-specific immune defect in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is correlated with a dysregulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115(3):508–514. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00812.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guoping Peng SL. Wei W. Zhen S. Yiqiong C. Zhi C. Circulating CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells correlate with chronic hepatitis B infection. Immunology. 2008;123:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeroen N. van der Molen1 RG. Kuipersa EJ. Kustersa JG. Janssen HLA. Inhibition of viral replication reduces regulatory T cells and enhances the antiviral immune response in chronic hepatitis B. Virology. 2007;361(1):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker MR. Gersuk VH. Bènard A. Van Landeghen M. Buckner JH. Ziegler SF. Induction of FoxP3 and acquisition of T regulatory activity by stimulated human CD4+CD25− T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1437. doi: 10.1172/JCI19441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franzese OKP. Gehring AJ. Gotto J. Williams R. Maini MK. Bertoletti A. Modulation of the CD8+ T-cell response by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:3322–3328. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3322-3328.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoop JN vdMR. Baan CC. van der Laan LJ. Kuipers EJ. Kusters JG. Janssen HL. Regulatory T cells contribute to the impaired immune response in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2005;41:771–778. doi: 10.1002/hep.20649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenwald RJ. Freeman GJ. Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:515–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okazaki T. Honjo T. The PD-1-PD-L pathway in immunological tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisicaro P. Valdatta C. Massari M, et al. Antiviral intrahepatic T-cell responses can be restored by blocking programmed death-1 pathway in chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(2):682–693. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Z. Zhang JY. Wherry EJ, et al. Dynamic programmed death 1 expression by virus-specific CD8 T cells correlates with the outcome of acute hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(7):1938–1949. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raziorrouh B. Schraut W. Gerlach T, et al. The immunoregulatory role of CD244 in chronic hepatitis B infection and its inhibitory potential on virus-specific CD8+ T-cell function. Hepatology. 2010;52:1935–1948. doi: 10.1002/hep.23936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crane M. Sirivichayakul S. Chang JJ, et al. No increase in hepatitis B virus (HBV)-specific CD8+ T cells in patients with HIV-1-HBV coinfections following HBV-active highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 2010;84(6):2657–2665. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02124-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang HH. Guo F. Fei R, et al. [Inhibition of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in chronic hepatitis B patients] Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2008;88(8):511–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng G. Li S. Wu W. Sun Z. Chen Y. Chen Z. Circulating CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells correlate with chronic hepatitis B infection. Immunology. 2008;123(1):57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nan XP. Zhang Y. Yu HT, et al. Circulating CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells and expression of PD-1 and BTLA on CD4+ T cells in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Viral Immunol. 2010;23(1):63–70. doi: 10.1089/vim.2009.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.TrehanPati N. Geffers R. Sukriti , et al. Gene expression signatures of peripheral CD4+ T cells clearly discriminate between patients with acute and chronic hepatitis B infection. Hepatology. 2009;49(3):781–790. doi: 10.1002/hep.22696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyaaki H. Zhou H. Ichikawa T, et al. Study of liver-targeted regulatory T cells in hepatitis B and C virus in chronically infected patients. Liver Int. 2009;29(5):702–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rushbrook SM. Hoare M. Alexander GJ. T-regulatory lymphocytes and chronic viral hepatitis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007;7(11):1689–1703. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.11.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furuichi Y. Tokuyama H. Ueha S. Kurachi M. Moriyasu F. Kakimi K. Depletion of CD25+CD4+ T cells (Tregs) enhances the HBV-specific CD8+T cell response primed by DNA immunization. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(24):3772–3777. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i24.3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boni C. Penna A. Bertoletti A, et al. Transient restoration of anti-viral T cell responses induced by lamivudine therapy in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2003;39(4):595–605. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kondo Y. Asabe S. Kobayashi K, et al. Recovery of functional cytotoxic T lymphocytes during lamivudine therapy by acquiring multi-specificity. J Med Virol. 2004;74(3):425–433. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pan XC. Yang F. Chen M. [The effect of telbivudine on peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells and its significance in patients with chronic hepatitis B] Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2008;16(12):885–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hui CK. Lau GK. Advances in immunomodulating therapy of HBV infection. Int J Med Sci. 2005;2(1):24–29. doi: 10.7150/ijms.2.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang W. Dong SF. Sun SH. Wang Y. Li GD. Qu D. Coimmunization with IL-15 plasmid enhances the longevity of CD8 T cells induced by DNA encoding hepatitis B virus core antigen. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(29):4727–4735. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i29.4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinter AL. Godbout EJ. McNally JP, et al. The common gamma-chain cytokines IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21 induce the expression of programmed death-1 and its ligands. J Immunol. 2008;181(10):6738–6746. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radziewicz H. Dunham RM. Grakoui A. PD-1 tempers Tregs in chronic HCV infection. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(3):450–453. doi: 10.1172/JCI38661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoyos V. Savoldo B. Quintarelli C, et al. Engineering CD19-specific T lymphocytes with interleukin-15 and a suicide gene to enhance their anti-lymphoma/leukemia effects and safety. Leukemia. 2010;24(6):1160–1170. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.