Abstract

Extracellular nucleotides are potent signaling molecules mediating cell-specific biological functions, mostly within the processes of tissue damage and repair and flogosis. We previously demonstrated that adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) inhibits the proliferation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-hMSCs), while stimulating, in vitro and in vivo, their migration. Here, we investigated the effects of ATP on BM-hMSC differentiation capacity. Molecular analysis showed that ATP treatment modulated the expression of several genes governing adipogenic and osteoblastic (ie, WNT-pathway-related genes) differentiation of MSCs. Functional studies demonstrated that ATP, under specific culture conditions, stimulated adipogenesis by significantly increasing the lipid accumulation and the expression levels of the adipogenic master gene PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma). In addition, ATP stimulated osteogenic differentiation by promoting mineralization and expression of the osteoblast-related gene RUNX2 (runt-related transcription factor 2). Furthermore, we demonstrated that ATP stimulated adipogenesis via its triphosphate form, while osteogenic differentiation was induced by the nucleoside adenosine, resulting from ATP degradation induced by CD39 and CD73 ectonucleotidases expressed on the MSC membrane. The pharmacological profile of P2 purinergic receptors (P2Rs) suggests that adipogenic differentiation is mainly mediated by the engagement of P2Y1 and P2Y4 receptors, while stimulation of the P1R adenosine-specific subtype A2B is involved in adenosine-induced osteogenic differentiation. Thus, we provide new insights into molecular regulation of MSC differentiation.

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent adult stem cells that can be isolated from several tissues, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood [1,2]. MSCs can be expanded and induced to differentiate in vitro and in vivo into several tissue lineages originating from the three germinal layers [3,4]. MSCs are thought to be immunoprivileged, since they do not express costimulatory molecules that are involved in the activation of T cells for transplant rejection [5–7]. Moreover, MSCs display immunomodulatory properties by inhibiting the activation, proliferation, and function of immune cells by different mechanisms of action [7,8]. Although some reports, showing evidence of MSC immunogenicity in vivo [9–12], suggest a more cautious approach, a growing body of preclinical and clinical studies indicates MSCs as a promising tool for cell therapy, bioengineering, and gene therapy [13–16].

Extracellular adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) and other nucleotides elicit a wide array of cell-specific responses [17–20]. In particular, ATP is a major signaling molecule during flogosis and in the tissue repair [21–23]. Nucleotide activity is mediated by specific purinerigic receptors (P2Rs) expressed on many different cell types. So far, seven P2XR subtypes (P2X1R to 7) and eight P2YR subtypes (P2Y1R, 2, 4, 6, 11, 12, 13, and 14) have been identified [24]. P2XRs are ligand-gated ion channels, while P2YRs are G-protein-coupled receptors [25,26]. The pattern of expression of different P2R subtypes on cell membrane influences activity and the ultimate effect of nucleotides. Moreover, the intracytoplasmic signal cascade activated by extracellular nucleotides is the result of the balance between binding to specific receptors and their metabolism. Indeed, ATP is converted to adenosine in intracellular and extracellular spaces by the sequential activity of specific nucleotide-hydrolyzing enzymes, such as the ecto-NTPDase CD39 and the ecto-5'-nucleotidase CD73 (NT5E) [27,28]. However, the resulting adenosine is not a mere degradation product, but it is, in turn, a physiological regulator of a number of metabolic activities [21,29–31]. Adenosine binds to P1 plasma membrane receptors, which are activated by various ranges of adenosine concentrations. Four subtypes of P1Rs have been cloned so far, namely A1, A2A, A2B, and A3. All P1Rs are typical G-protein-coupled receptors [24,32].

We have recently demonstrated that purinergic signaling modulates several biological functions of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-hMSCs), which express functional P2R subtypes. Gene expression profiling (GEP) and functional studies revealed the ATP inhibited the proliferation and the clonogenic potential of MSCs. Moreover, ATP potentiated chemotactic response of BM-hMSCs to CXCL12, and increased their spontaneous migration in vitro and homing in vivo [33]. Other studies from our group have also shown that human hematopoietic stem cells express functional P2XRs and P2YRs of several subtypes, and that the stimulation of CD34+ cells with extracellular nucleotides improves their clonogenic capacity, migration, and engraftment in immunodeficient mice [34,35]. Conversely, ATP inhibits proliferation and migration of leukemic cells [36].

Here, we show that extracellular ATP, through specific receptors, stimulates the differentiation capacity of BM-hMSCs to the adipogenic lineage, while the ATP degradation product adenosine induces osteogenic differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

ATP, UTP, and adenosine were from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO). CD73 inhibitor (α, β metylene adenosine), CD39 inhibitor (ARL67156), P2Y2R agonist (MRS2768), P2Y1R antagonist (MRS 2279), P2Y11R antagonist (NF340), P2Y12R antagonist (ARC66096), P2Y6R antagonist (MRS2578), P2X7R antagonist (KN62), A2B adenosine receptor antagonist (PSB1115), and the generic adenosine receptor antagonist (CGS15943) were all from Tocris (Bristol, UK). P2Y2R/P2Y4R agonist (INS45973) was kindly provided by Inspire Pharmaceutical (Durham, NC). Pertussis toxin (PTX) from Bordetella pertussis was from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell isolation and culture

hMSCs were isolated from BM aspirates of normal donors after obtaining informed consent, as previously described [15]. Briefly, the mononuclear cell fraction was separated by centrifugation over a Ficoll-Paque gradient (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ), resuspended in a proliferation medium consisting of a low-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Lonza, Milan, Italy), 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Gibco–Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 1% antibiotics (MP Biomedicals, Verona, Italy), and plated at an initial seeding density of 1.6×105 cells/cm2. After 3 days, the nonadherent cell fraction was removed by rinsing cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and monolayers of adherent cells were cultured until they reached 70%–90% confluence. Cells were then trypsinized (0.25% trypsin with 0.1% EDTA; EuroClone, Pero, Italy), subcultured at a density of 3.5×103 cells/cm2, and used for experiments within passages 3 to 5.

BM-hMSCs were treated with 1 mM ATP or with 100 μM adenosine or with solvent alone 24 h before starting the osteogenic or adipogenic differentiation protocols. Doses of purines used in this study were selected based on previous work [33] and dose–response curves. Briefly, we tested different concentrations of ATP, ranging from 500 μm to 2 mM, and we evaluated the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ), the adipogenic differentiation master gene. Similarly, we tested increasing doses of adenosine (ie, 50 μm, 100 μm, and 200 μM) on the expression of runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), the osteogenic differentiation master gene. The level of induction of PPARγ increased in a dose-dependent manner. However, the highest dose of ATP (ie, 2 mM) induced a slightly toxic effect (unpublished data). Therefore, we decided to use 1 mM ATP in all experiments. Adenosine was used at the concentration that produced the maximum level of induction of RUNX2 (ie, 100 μM) (data not shown). In some experiments, BM-hMSCs were treated with 1 mM ATP for the first 3 days of differentiation. The results of these experiments were not significantly different from those where MSCs were preincubated with ATP.

Adipogenic and osteogenic induction

To induce adipogenic differentiation, BM-hMSCs were seeded at 2.1×104 cells/cm2 on a Lab-Tek II coverglass chamber (Nalge-Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) and grown for 3 days in an adipogenic induction medium (Lonza) containing additional h-Insulin, l-glutamine, mesenchymal cell growth supplement (MCGS), dexamethasone, indomethacin, 3-isobuty-I-methyl-xanthine, and pen/strep, followed by 3 days in an adipogenic maintenance medium containing h-Insulin, l-glutamine, MCGS, and pen/strep (1 cycle). Both steps were repeated up to day 12 (indicated in the results as second cycle) or 18 (indicated in the results as third cycle), when cell cultures were stopped for histological staining and total RNA extraction.

To induce osteogenic differentiation, BM-hMSCs were seeded at 3.1×103 cells/cm2 and grown in an osteogenic differentiation medium (Lonza) containing l-glutamine, MCGS, dexamethasone, ascorbate, β-glycerophosphate, and pen/strep. The media were replaced every 3–4 days. Cell cultures were stopped at days 14 (2 weeks) and 21 (3 weeks) for histological staining and total RNA extraction.

Oil-red-O and Alizarin Red staining procedure

Fat droplets within adipocytes were identified using the Oil-red-O staining method. Briefly, cells were fixed in 10% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and rinsed in 60% isopropanol. Isopropanol was removed, and the wells were completely dried and stained with a 0.6% (w/v) Oil red O solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min at room temperature with gentle rotation. For quantification, cell monolayers were washed extensively with water to remove the unbound dye, and then 100% isopropanol was added to the stained cultures. The absorbance of the extract was assayed by a spectrophotometer at 500 nm (Multiskan Ex; Thermo Electron Corporation Waltham, MA). Each sample was measured in duplicate wells. The final concentration was determined using an Oil red O standard curve.

Calcium deposition was determined using Alizarin Red staining. Briefly, cells were fixed in 10% PFA in PBS for 15 min at room temperature and rinsed with PBS and distilled water. Fixed cultures were stained with 40 mM Alizarin Red solution (Sigma-Aldrich) pH 4.2, for 75 min at room temperature with gentle agitation and rinsed with distilled water. Alizarin Red was extracted from fixed cells by incubating in 10% (w/v) cethylpyridinium chloride solution (Sigma-Aldrich) in 10 mM sodium phosphate for 15 min at room temperature with gentle agitation. The absorbance of extracted Alizarin Red was measured at 570 nm. Each sample was measured in duplicate wells. The final concentration was determined using the appropriate standard curve.

Total RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated using Rneasy Micro kit (Qiagen, MI, Italy) according to the manufacturer's instructions and quantified by a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). 1μg of denatured total RNA was reverse transcribed using Promega Improm II kit and random hexamers in a 20μL final volume according to manufacturer's instruction (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using the ABI-PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

The qRT-PCRs were performed using a 96-well Optical Reaction Plate and a 7700 ABI PRISM system (Applied Biosystem). For each PCR run, 1 μL of cDNA product was mixed with 2×Platinum Super mix (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 25 μL. The thermal cycling conditions consisted of an initial stage of 50°C for 2 min, and 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of melting at 95°C for 15 s, and annealing at 60°C for 1 min. Threshold cycle (Ct) values for specific and control gene were determined automatically using a 7700 ABI PRISM system (Applied Biosystem). Relative quantification was calculated using ΔCt comparative method [37], and GAPDH was used as the endogenous reference gene. Briefly, the relative level of a specific mRNA, PPARγ and RUNX2, was calculated by subtracting the Ct value of the control gene from the Ct value of the specific gene. PPARγ or RUNX2 mRNA levels in untreated/undifferentiated cells for each time of differentiation were taken as 1. All reactions were performed in duplicate, and samples were obtained from at least 4 independent experiments.

Primer probes for PPARγ, Hs01115513_m1, RUNX2, Hs00231692_m1, GAPDH, Hs00266705_g1, P2Y1 Hs 00704965_s1, P2Y2 Hs00175732_m1, P2Y4 Hs00267404_s1, P2Y6 Hs00602548_m1, P1A1 Hs 00379752_m1, P1A2A Hs 00386497_m1, P1A2B Hs00169123_m1, and P1A3 Hs 00252933_m1 were purchased from Applied Biosystems.

Microarrays

Microarray data utilized for the analysis of genes differentially expressed in undifferentiated BM-hMSCs untreated versus treated with ATP (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd) originate from Ferrari et al. [33] and were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus MIAME compliant public database, at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=dlmdfaeamiqioxs&acc=GSE14566

For microarray analysis in differentiated cells (Fig. 1), BM-hMSCs were pretreated with 1 mM ATP (ATP-pre-treat) or with solvent alone (untr) for 24 h, before initiating the osteogenic or adipogenic differentiation protocols as described above. ATP-pretreated and untreated BM-hMSCs were cultured also in the medium without differentiation-inducing agents (und) (for sample nomenclature, see Supplementary Table S1). After 3 weeks of osteogenic/adipogenic differentiation, ATP-treated or untreated differentiated or undifferentiated BM-hMSCs were collected and lyzed in the QIAZOL Buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Total RNA from BM-hMSCs was extracted using an miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. Disposable RNA chips (Agilent RNA 6000 Nano LabChip kit; Agilent Technologies, Waldbrunn, Germany) were used to determine the concentration and purity/integrity of RNA samples using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies) was used to evaluate the RNA sample concentration, and 260/280 and 260/230 nm ratios were considered to verify the purity of total RNA. Microarray analysis was performed starting from pooled RNA obtained from 5 independent experiments.

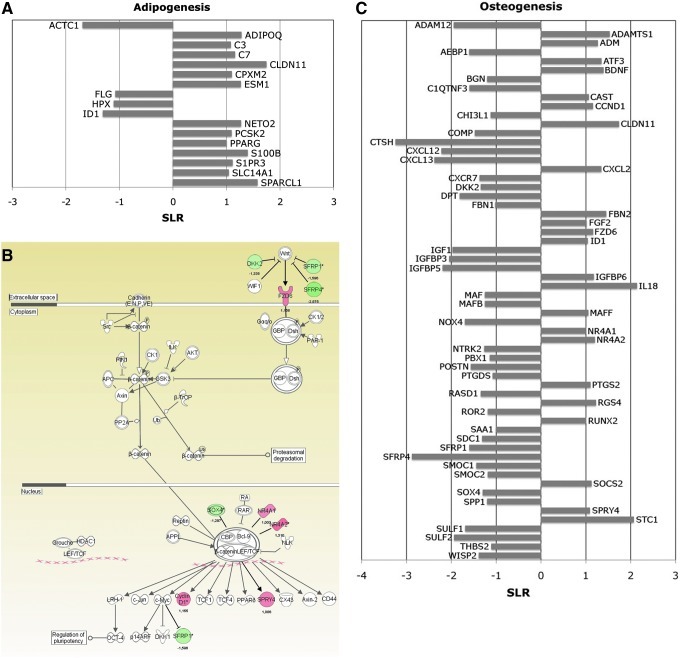

FIG. 1.

Microarray analysis in adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP)-pretreated differentiated human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-hMSCs). (A) Gene expression profile of untreated or ATP-pretreated BM-hMSCs after 3 weeks of adipogenic differentiation induction. Changes in gene expression are reported on the x-axis as signal log ratio (SLR) in the pairwise comparison ATP-pretreated versus untreated BM-hMSCs differentiated to adipocytes. (B) Ingenuity pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes in ATP-pretreated BM-hMSCs compared with untreated counterpart after 3 weeks of osteogenic differentiation. Green and red colors indicate genes down- and upregulated, respectively, in the pairwise comparison ATP-pretreated versus untreated BM-hMSCs differentiated to osteocytes. Expression of WNT-signaling pathway components resulted modulated by ATP pretreatment. (C) Gene expression profile of untreated or ATP-pretreated BM-hMSCs after 3 weeks of osteogenic differentiation. Changes in gene expression are reported on the x-axis as SLR in the pairwise comparison ATP-pretreated versus untreated BM-hMSCs differentiated to osteocytes. For sample nomenclature, see Supplementary Table S1. For annotations of genes included in this figure, see Supplementary Table S3.

GeneAtlas 3′IVT Express Kit as well as Affymetrix HG-U219 array strip hybridization, staining, and scanning were performed, using the Affymetrix GeneAtlas standard protocols (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). All the data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus MIAME compliant public database, at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=dlmdfaeamiqioxs&acc=GSE37237. Gene expression data were imported into Partek Genomics Suite 6.5 (Partek, St. Louis, MO) as CEL files using default parameters. Raw data were preprocessed, including background correction, normalization, and summarization, using robust multiarray average analysis, and expression data were log2-transformed. Differentially expressed genes were selected as the sequences showing signal log ratio (SLR) ≥1 or ≤−1 in the pairwise comparisons between ATP-pretreated and untreated samples. Ingenuity pathways analysis (IPA) (www.ingenuity.com) was used to examine selected lists of genes to study pathways modulated by treatment.

Flow cytometry

Dual-color immunofluorescence was performed using anti-human phycoerythrin-conjugated CD39 (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and anti-human fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated CD73 (BD Pharmingen) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). Negative controls were isotype-matched irrelevant mAbs. For cell-surface staining, cells (5×105) were incubated in the dark for 30 min at 4°C in PBS–1% BSA. Cells were rinsed in PBS and analyzed using BD FACSCanto™II equipment (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). A minimum of 10,000 events was collected in list mode on FACSDiva software.

Statistical analysis

Results are given as mean±SD. Data collected from all experiments were analyzed using the Student's t-test. P≤0.05 was considered as statistically significant and indicated with * 0.001≤P≤0.02 was considered as highly significant and indicated with ** P>0.05 was considered as not significant.

Results

Gene expression profile of ATP-treated undifferentiated BM-hMSCs

We previously demonstrated that ATP treatment of BM-hMSCs upregulated many genes involved in skeletal development, bone mineralization, regulation of bone remodeling, and osteoblast differentiation [33]. In this article, further analysis of differentially expressed genes showed that ATP induces, even in the absence of any differentiation stimuli, the expression of master regulatory genes of osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation in BM-hMSCs. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, different genes involved in osteogenic differentiation are upregulated in ATP-treated BM-hMSCs compared to the untreated sample, such as osteoblastic transcription factors (ie, RUNX2 [38] and FOXO1 [39]), osteoblastic markers (ie, ANKH, BGLAP, and SPP1 [40,41]), and osteogenic growth factors (ie, BMP2, BMP6, WISP2, and IGFBP5 [42–45]). Moreover, ATP treatment of BM-hMSCs increased the expression of adipogenic transcription factors (ie, CEBPA, PPARGC1A, and CEBPB) [46] and adipocyte-specific proteins (ie, ADFP, PC, and SPG20 [47–49]) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Finally, although ATP upregulated some genes associated with chondrocyte differentiation, such as CHI3L1, CRTAP, and BMP1 [50,51], none of master regulator genes of this lineage resulted modulated (Supplementary Fig. S1; for annotation of genes included in this figure see Supplementary Table S2). Thus, based on these data obtained in undifferentiated BM-hMSCs, we studied the effects of ATP on osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation.

GEP of ATP-treated BM-hMSCs in adipogenic and osteogenic culture conditions

BM-hMSCs were transiently exposed to ATP (1 mM) for 24 h (ATP pre-treat) before starting differentiation induction. BM-hMSCs were then cultured under adipogenic or osteogenic conditions as described in the Materials and Methods section, and GEP was analyzed after 3 weeks of culture.

For comparison, we first analyzed the GEP of undifferentiated BM-hMSCs (und) and that of BM-hMSCs differentiated to the osteogenic (untr osteo) and adipogenic (untr adipo) lineages without addition of ATP. As expected, osteogenic transcription factors such as RUNX2 and FOXO1 and adipogenic transcription factors PPARγ, CEBPA, and CEBPD were increased in differentiated MSCs even in the absence of ATP (not shown).

However, when BM-hMSCs were preincubated with ATP and then differentiated to the adipogenic lineage (ATP pre-treat adipo), some master genes involved in adipogenesis such as ADIPOQ, a PPARγ [52] and CEPBPA [53] target gene, and several adipocyte differentiation markers such as ESM1 [54] and S100B [55] were significantly increased compared to untreated counterpart (untr adipo). Moreover, ID1, a key transcription factor in osteogenic differentiation, was downregulated, as previously reported [56] (Fig. 1A).

Furthermore, to study pathways modulated by ATP treatment in osteogenic differentiated cells, we compared ATP-pretreated (ATP pre-treat osteo) versus untreated BM-hMSCs (untr osteo) differentiated versus osteogenic lineage and uploaded a list of 290 differentially expressed transcripts to IPA software (see the Materials and Methods section) (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, we found that ATP modulated several genes coding for proteins involved in the WNT/β-catenin pathway, involved in supporting MSC osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 1B). In particular, the expression of WNT receptor FZD6 [57], beta-catenin interactor NR4A orphan nuclear receptors (NR4A1 and NR4A2) [58], and WNT target genes as CCND1 (cyclin D1) and SPRY4 were increased in ATP-treated cells. Consistently, some WNT/β -catenin signaling pathway inhibitors, such as DKK2 [59], SFRP1 [60], and SFRP4 [61], were downregulated (Fig. 1B). Moreover, as shown in Fig. 1C, the expression of many other genes important for osteoblastic differentiation was modulated by ATP treatment. In particular, among upregulated transcripts, we found signal transduction proteins involved in osteogenic differentiation, such as CAST [62], ID1, and SOCS2 [63]; osteogenic growth factors, such as FGF2, STC1 [64], ADM, and IL18, described as a mitogen to the osteogenic and chondrogenic cells [65], and osteoblastic differentiation markers, such as ADAMTS1 and CLDN11. Among ATP-downregulated genes, we found PBX1, a transcription factor that impaired osteogenic commitment of pluripotent cells and the differentiation of osteoblasts [66] and other transcripts whose expression was inversely related to cell mineralization and terminal differentiation, such as POSTN [67], DPT, ROR2 [68], and SOX4 [69] (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, ATP increased the expression of FBN2, but downregulated FBN1 (Fig. 1C). FBN1 and FBN2 are structural components of extracellular microfibrils and critical regulators of bone formation. The increase of FBN2 and downregulation of FBN1 resulted in the promotion of osteogenic differentiation [70] (For annotations of genes included in this paragraph see Supplementary Table S3).

Taken together, these data demonstrate the role of ATP in promoting osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of MSCs.

Exogenously added ATP increases BM-hMSC adipogenic differentiation

We then studied at the functional level, the effects of ATP on adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of BM-hMSCs.

To this aim, BM-hMSCs were transiently exposed to ATP before inducing differentiation as previously described. BM-hMSCs were then cultured under adipogenic conditions as described in the Materials and Methods section. Differentiated cells were analyzed after 2 and 3 weeks.

First, we asked whether ATP treatment would be able to stimulate the expression of PPARγ, a ligand-dependent transcription factor known to be a primary inducer of adipogenesis [71]. As shown in Fig. 2A, qRT- PCR confirmed that 2 weeks of adipogenic differentiation resulted in 15–20-fold-increase of PPARγ mRNA as compared to undifferentiated cells (P<0.001), and that preincubation with ATP induced a further 10–15-fold-increase in PPARγ mRNA expression as compared to untreated cells (P<0.01). Similar results were observed after 3 weeks of differentiation (Fig. 2A).

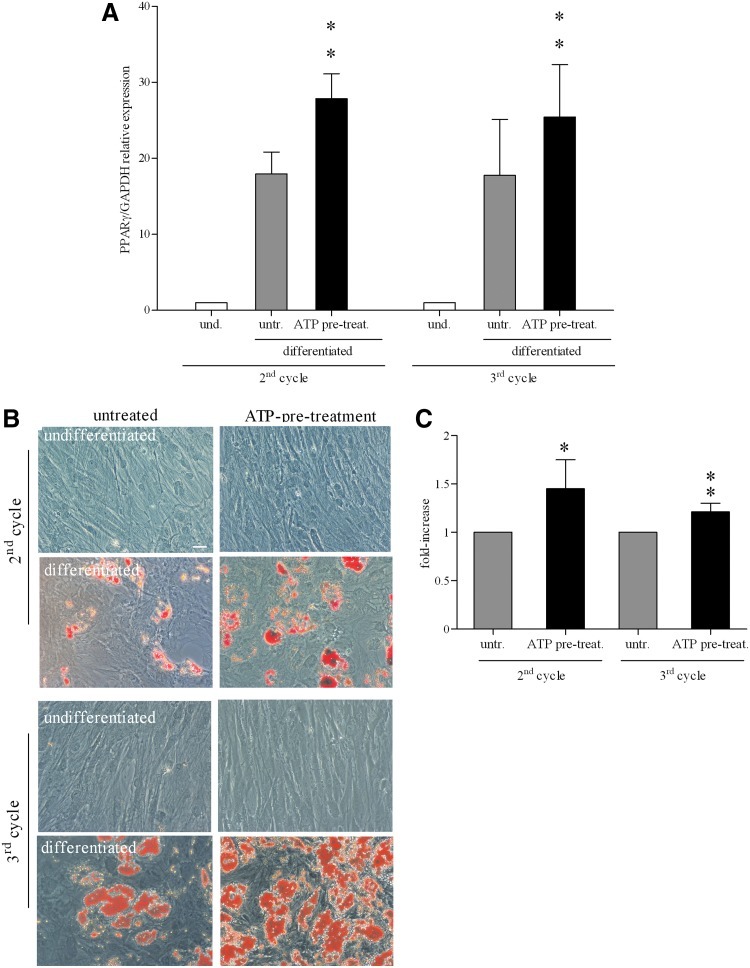

FIG. 2.

Effect of ATP during differentiation of BM-hMSCs into adipocytes. (A) Quantitative real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) mRNA (PPARγ/GAPDH relative levels) in undifferentiated (white histograms) and differentiated cells, untreated (light gray histograms), or treated with ATP (black histograms), after 2 (second cycle) or 3 weeks (third cycle) of culture. mRNA levels of PPARγ present in differentiated cells were normalized to that in undifferentiated cells (assigned a value of 1) (mean±SD of 8 independent experiments), **0.01≤P≤0.001. und., undifferentiated; untr., untreated; ATP pre-treat., ATP pre-treatment. (B) Representative microphotos of Oil-red-O-stained BM-hMSCs cultured for 2 (second cycle) or 3 weeks (third cycle) in a proliferation medium (undifferentiated), first and third row, or in adipogenic condition (differentiated), second and fourth row, untreated (left column) or treated with ATP (right column). Magnification 20×. Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Quantitative destaining of adipogenic differentiated BM-hMSCs, untreated (light gray histograms) or treated with ATP (black histograms), stained with Oil red O. The graphs indicated the fold increase in the dye concentration, calculated from the appropriate standard curve, and taking the value in untreated cells as 1 (mean±SD of 4 independent experiments), *P<0.05; **P<0.001.

We then analyzed differentiated cultures under the microscope. After 2 weeks of adipogenic differentiation (second cycle), numerous lipid drops could be observed in the intracellular space of differentiated cells. Lipid content of the cells was demonstrated through Oil red O staining. As shown in Fig. 2B, adipogenesis-related accumulation of lipids was more evident in ATP-treated cells with respect to untreated cultures. Lipid drops were not observed in the cells cultured in the medium without differentiation-inducing agents with or without ATP (Fig. 2B). The destaining of the cultures and the evaluation of the dye extract absorbance by a spectrophotometer showed a significant increase in dye concentration (a measure of the total lipid content of the culture) in ATP-treated cells in comparison with untreated cells (Fig. 2C). After 3 weeks of differentiation (third cycle), these differences were still present (Fig. 2C). The data indicated that extracellular ATP improved differentiation under adipogenic culture conditions.

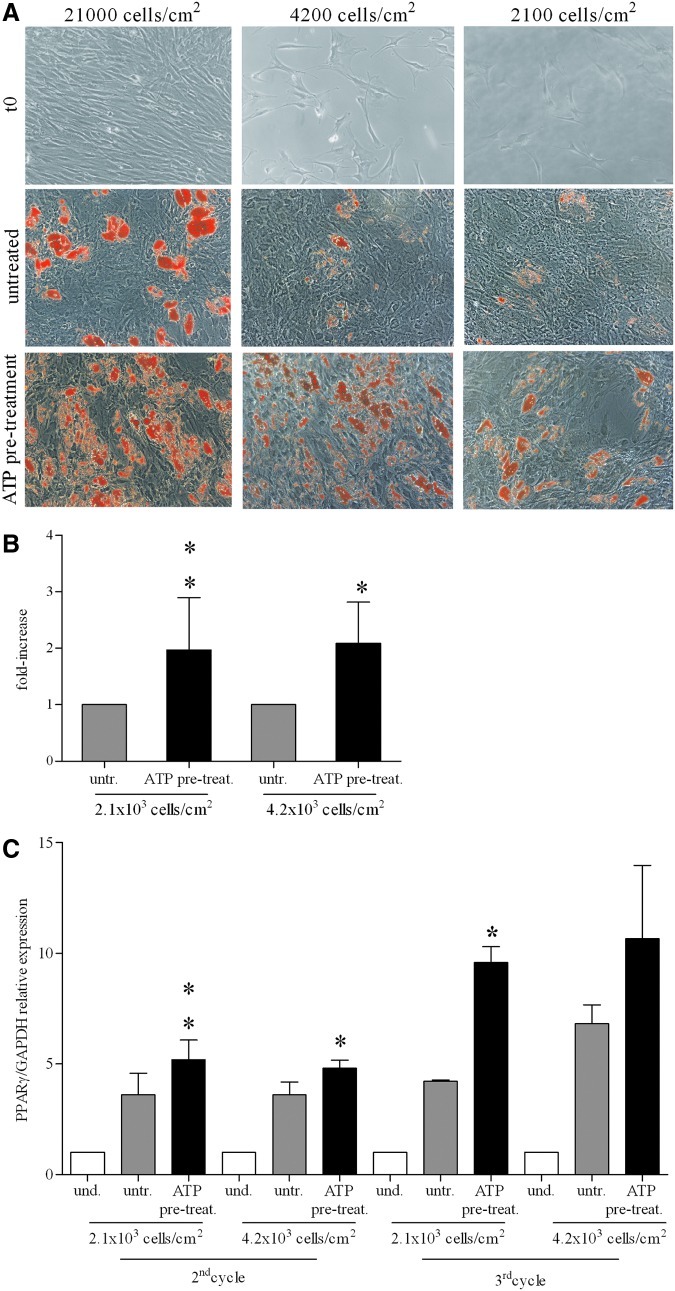

Furthermore, we asked whether ATP could improve BM-hMSC differentiation in adipocytes under suboptimal culture conditions (ie, treating preconfluent proliferating cells). To this aim, we seeded BM-hMSCs at low cell density: 5-fold (4.2×103 cells/cm2) and 10-fold (2.1×103 cells/cm2) less than the standard concentration (2.1×104 cells/cm2), respectively, and then we started the differentiation protocol. As shown in Fig. 3A, diluted, untreated cells poorly differentiated in adipocytes, whereas ATP-treated cells showed a massive adipocyte induction, as demonstrated by both Oil-red-O quantitative destaining (Fig. 3B) and PPARγ mRNA expression in qRT-PCR assay (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that extracellular ATP makes BM-hMSCs more sensitive to adipogenic hormones even before reaching confluence.

FIG. 3.

Effect of ATP on BM-hMSC adipogenic differentiation in preconfluent/proliferating culture conditions. (A) Examples of BM-hMSCs starting culture conditions (t0) in differentiation experiments at the indicated cell concentration (first row). Oil red O staining of BM-hMSCs cultured for 3 weeks in adipogenic conditions, untreated (second row) or treated with ATP (third row). Magnification 10×. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Quantification of Oil red O staining in BM-hMSCs untreated (light gray histograms) or treated with ATP (black histograms) at the indicated cell concentrations after 3 weeks of culture in adipogenic conditions. The dye concentration in untreated cells was taken as 1 (mean±SD of 2 independent experiments), *P<0.05; **P<0.01. (C) mRNA expression of PPARγ (PPARγ/GAPDH relative levels) quantified by qRT-PCR in undifferentiated (white histograms) and differentiated cells (light gray and black histograms), untreated or treated with ATP, at the indicated cell concentrations after 2 (second cycle) or 3 weeks (third cycle) of culture. mRNA levels of PPARγ present in undifferentiated cells at each cell concentration was taken as 1 (mean±SD of 2 independent experiments), *P<0.05; **P<0.01. Where not indicated the differences are not significant. und., undifferentiated; untr., untreated; pre-treat., ATP pre-treatment.

Effects of extracellular ATP on BM-hMSC osteogenic differentiation

We next tested the effect of ATP treatment on the differentiation of BM-hMSCs to osteoblasts. We first assessed, by qRT-PCR, the expression of the osteogenic marker gene RUNX2, a pivotal transcription factor involved in the regulation of osteogenesis [38]. Our data indicated that ATP treatment significantly increased RUNX2 expression both after 2 or 3 weeks of differentiation (Fig. 4A).

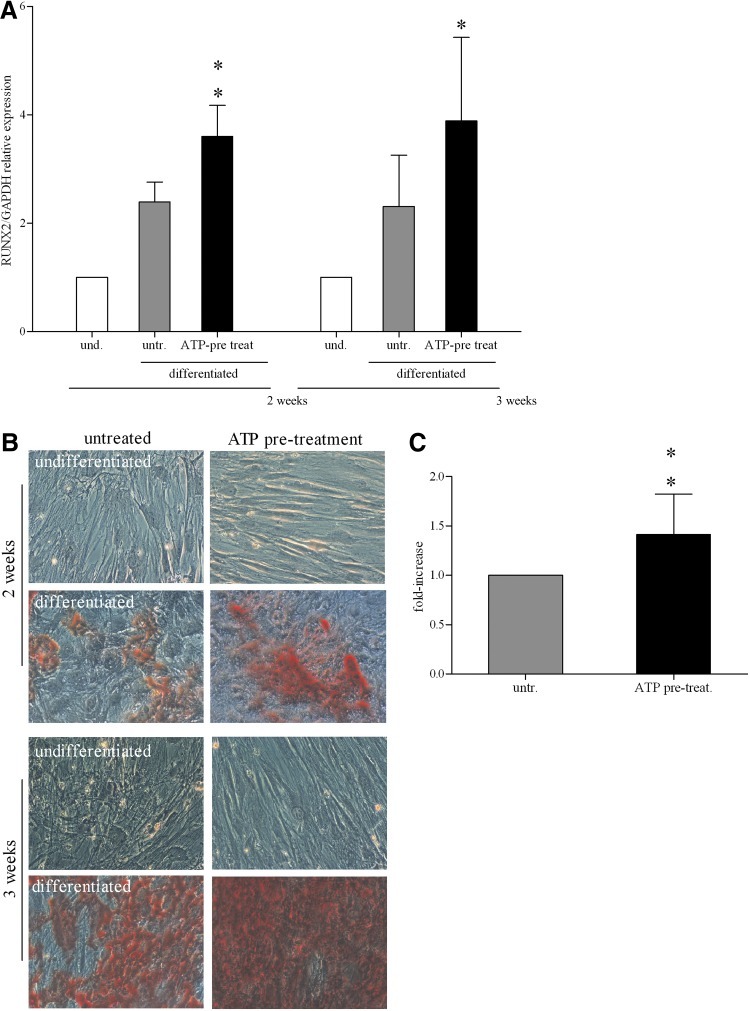

FIG. 4.

ATP stimulation of osteogenesis on BM-hMSCs. (A) mRNA expression of runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) (RUNX2/GAPDH relative levels) quantified by qRT-PCR in undifferentiated (white histograms) and differentiated BM-hMSCs (light gray and black histograms), untreated or treated with ATP, after 2 and 3 weeks of culture. mRNA levels of RUNX2 in undifferentiated cells at each time was taken as 1 (mean±SD of 10 independent experiments), *P<0.05, **P<0.01. und., undifferentiated; untr., untreated; pre-treat., ATP pre-treatment. (B) Alizarin Red staining of BM-hMSCs cultured for 2 and 3 weeks in a proliferation medium (undifferentiated), first and third row, or in osteogenic condition (differentiated), second and fourth row, untreated (left column) or treated with ATP (right column). Magnification 20×. Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Quantitative destaining of Alizarin Red-stained BM-hMSCs, untreated (light gray histograms) or treated with ATP (black histograms) after 3 weeks of differentiation. The graphs indicate the fold increase in the dye concentration, calculated from the appropriate standard curve and taking the value in untreated cells as 1 (mean±SD of 3 independent experiments), **P<0.01.

The analysis of mineralized area with Alizarin Red staining indicated that ATP pre-treatment enhanced the extent of mineralization of BM-hMSC-differentiated cultures compared to the untreated control (Fig. 4B). After 2 weeks of differentiation induction, the mineralization area was already present, but the concentration of Alizarin Red in all samples was too low to be measured. However, the quantification of alizarin red concentration at 3 weeks of differentiation confirmed a significant increase (P<0.01) in calcium deposition in ATP-treated BM-hMSCs as compared to untreated cells (Fig. 4C).

We previously reported that 24h exposure to 1 mM ATP significantly inhibited hMSC proliferation [33]. Since cell cycle arrest is a prerequisite for differentiation, this observation gives rise to the question of whether the effect we observed would be specifically induced by ATP treatment on differentiation or it would be mediated by proliferation arrest. To answer this question, we calculated the number of cells after 2 weeks of osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation (with and without ATP), and we compared those numbers with the number of seeded cells. Overall, the number of cells before and after the differentiation protocols (with and without ATP) did not change significantly (Supplementary Fig. S2A, S2B).

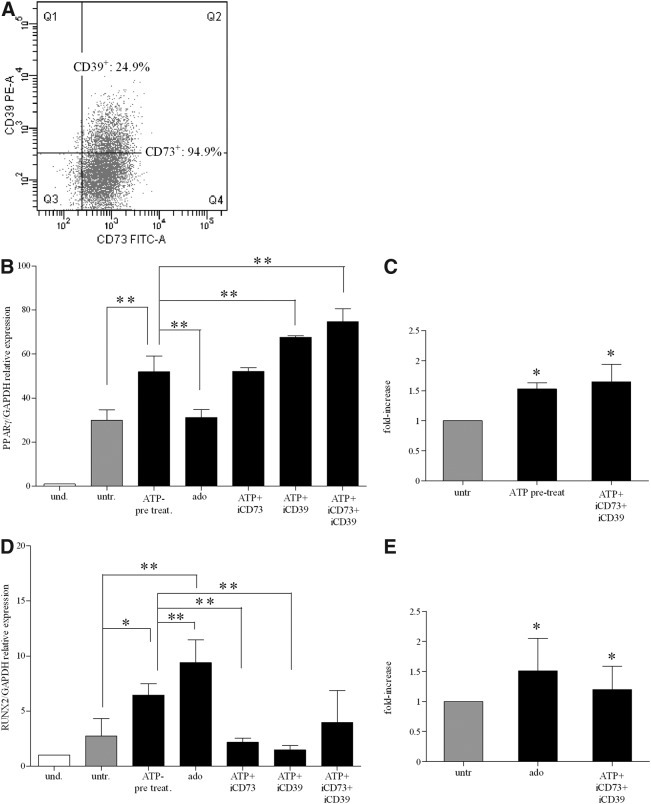

BM-hMSC differentiation is regulated by different signaling cascades

ATP degradation products, such as adenosine, act as signaling molecules in a variety of physiological processes [21,22,29–31]. Adenosine is readily formed from ATP by the sequential activity of CD39 and CD73 ectoenzymes, which are expressed on the MSC plasma membrane [27,28,72–74]. When we tested ectonucleotidase expression, we found that more than 90% of BM-hMSCs were CD73 positive, whereas CD39 was expressed in a median of 25.6% of the cells (range: 14.8%–59.9%) (Supplementary Table S4). Representative dot-plot displaying the coexpression of CD73 and CD39 in BM-hMSCs is shown in Fig. 5A. Thus, we hypothesized that ATP added to the culture medium of differentiating BM-hMSC cultures could be degraded by ectoenzymes to adenosine, which may be able to act as signaling molecules to induce adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation. To answer this question, we tested the effects of CD73- and CD39-specific inhibitors on PPARγ and RUNX2 expression in adipogenic and osteogenic conditions, respectively. Figure 5B shows that the pharmacological blockade of CD73 and CD39 by adding, respectively, α,β methylene-adenosine and ARL67156 to ATP-treated cultures maintained or potentiated the effects of ATP on PPARγ-dependent adipogenic differentiation. The addition of both ectoenzyme inhibitors had a synergistic effect. Accordingly, the PPARγ expression level was similar in adenosine-treated and untreated cultures (Fig. 5B). The potentiating effect of CD73 and CD39 inhibitors was confirmed by quantitative destaining of adipogenic differentiated cultures (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

Adenosine influence on adipogenesis and osteogenesis in BM-hMSCs. (A) Dot-plot of CD39/CD73 coexpression in a representative sample of BM-hMSCs. Percentages of positive cells are indicated. (B) mRNA expression of PPARγ (PPARγ/GAPDH relative levels) quantified by real-time PCR in differentiated cells (light gray and black histograms) at 3 weeks of differentiation after treatment with ATP or adenosine alone or in the presence of CD73 inhibitor (iCD73), or CD39 (iCD39) inhibitor, or both (mean±SD of 3 independent experiments), **P<0.001 when ATP-treatment (ATP pre-treat.), ATP in the presence of iCD73, or iCD39 or both were compared with untreated cells (untr.) (white histograms) (assigned value was 1) **P<0.001 comparing ATP pre-treat. versus ado; **P<0.001 when ATP in the presence of iCD39 or iCD39+iCD73 were compared with ATP pre-treat. Where not indicated the differences are not significant. (C) Quantification of Oil red O staining in BM-hMSCs untreated (light gray histograms) or treated with ATP (black histograms) or with ATP in the presence of CD73 inhibitor (iCD73) and CD39 inhibitor (iCD39) after 3 weeks of culture in adipogenic conditions. The dye concentration in untreated cells was taken as 1 (mean±SD of 2 independent experiments), *P<0.05. (D) mRNA expression of RUNX2 (RUNX2/GAPDH relative levels) by qRT-PCR analysis in undifferentiated (white histograms) (assigned value was 1) and differentiated cells (light gray and black histograms), after 3 weeks of differentiation after incubation with ATP or adenosine (ado) alone and ATP in the presence of CD73 inhibitor (iCD73), or CD39 inhibitor (iCD39) or both (mean±SD of 3 independent experiments), *P<0.05, **P<0.001, when ATP-treatment (ATP pre-treat.) and ado, respectively, were compared with untreated cells; **0.01≤P≤0.001, comparing ado, ATP+iCD73, and ATP+iCD73 versus ATP pre-treat (assigned value in undifferentiated cells was 1). Where not indicated the differences are not significant. (E) Quantitative destaining of Alizarin Red-stained BM-hMSCs, untreated (light gray histograms) or treated with ado (black histograms) or with ATP in the presence of CD73 inhibitor (iCD73) and CD39 inhibitor (iCD39) (mean±SD of 2 independent experiments), after 3 weeks of differentiation. The graphs indicate the fold increase in the dye concentration, calculated from the appropriate standard curve and taking the value in untreated cells as 1. *P<0.05.

Conversely, we found that inhibition of CD73 and CD39 in ATP-treated cells decreased RUNX2 expression levels to that of untreated cells. Moreover, addition of adenosine strongly stimulated RUNX2 upregulation (Fig. 5D). Similar results were obtained by the quantification of Alizarin Red concentration (Fig. 5E). Accordingly, incubation of ATP with the nucleotide-hydrolyzing enzyme apyrase increased RUNX2 expression (data not shown). Taken together, our data suggest that ATP exerts a direct stimulatory effect on adipogenic differentiation, and its degradation to adenosine abolishes ATP activity. Conversely, osteogenesis is induced by adenosine, resulting from the degradation of ATP by ectoenzymes.

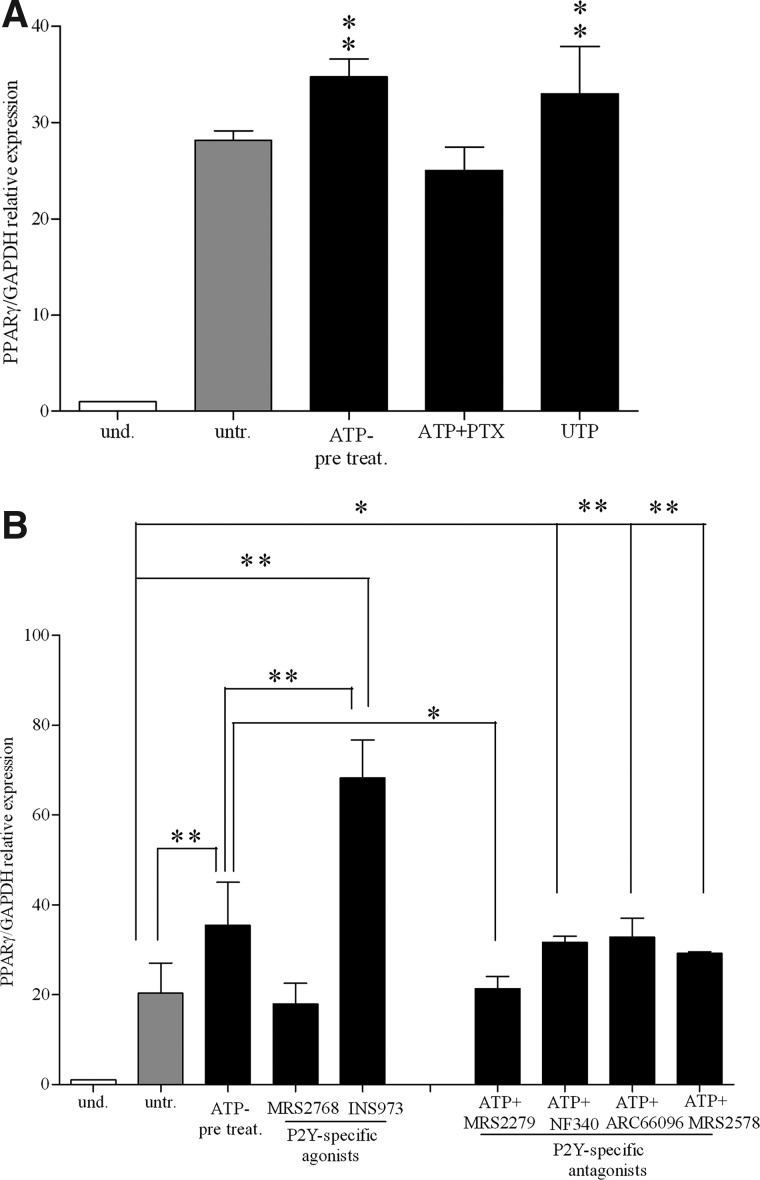

Signaling pathway of ATP-stimulated adipogenic differentiation

In a previous work, we demonstrated that BM-hMSCs express all P2R subtypes cloned so far, except for P2X2R, and that they are functionally active [33].

PTX from B. pertussis is a potent inhibitor of G-protein-coupled receptors [75]. Since P2YRs, but not P2XRs, are G-protein-coupled receptors, we used PTX to assess whether ATP-dependent increase of adipogenic differentiation was mediated by P2X or P2Y receptor stimulation. As shown in Fig. 6A, ATP failed to increase PPARγ expression levels in presence of PTX (100 ng/mL), indicating that ATP modulates adipogenic differentiation by stimulating G-protein-coupled P2YR. Furthermore, UTP, known to be an high-affinity ligand for P2Y2R, P2Y4R, and P2Y6R receptors [26], had a stimulatory effect similar to that of ATP on PPARγ expression (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Purinergic pathway stimulation during adipogenesis in BM-hMSCs. (A) PPARγ mRNA expression (PPARγ/GAPDH relative levels) after treatment with ATP, UTP, or ATP in the presence of pertussis toxin (PTX after 3 weeks of differentiation in adipogenic medium) (black histograms) (mean±SD of 3 independent experiments). Using untreated cells as the reference group, **P<0.02. Where not indicated the differences are not significant. und., undifferentiated; untr., untreated; ATP pre-treat., ATP pre-treatment. (B) mRNA expression of PPARγ (PPARγ/GAPDH relative levels) by qRT-PCR in undifferentiated (white histograms) and differentiated cells (light gray and black histograms), after 3 weeks of differentiation. Differentiated cells were treated with ATP alone or with MRS2768, a P2Y2R-specific agonist, or with INS45973, a P2Y2R/P2Y4R agonist, or with ATP in the presence of MRS2279, a P2Y1R-specific antagonist, or a P2Y11R- (NF340) or a P2Y12R- (ARC66096) specific antagonist, or P2Y6R- (MRS2578) specific antagonist (mean±SD of 4 independent experiments). Using untreated cells as the reference group, **P<0.01 for ATP-pretreatment and ATP+ARC66096; **P<0.001 for INS45973; **P<0.02 for ATP+MRS2578; *P<0.05 for ATP+NF340, not significant for ATP+MRS2279. Using ATP-pretreatment as the reference group **P<0.01 for INS45973, *P<0.05 for ATP+MRS2279, not significant for the others (assigned value in undifferentiated cells was 1).

To dissect out the role of the different receptor subtypes during adipogenic differentiation, we used currently available P2R agonists and antagonists. Indeed, many of the P2YR subtypes are still lacking potent and selective synthetic agonists and antagonists. These reagents are considered effective stimulators and inhibitors of P2R. As shown in Fig. 6B, MRS2768, a P2Y2R agonist, did not substantially modify the PPARγ expression level respect to untreated cells, while the P2Y2R/P2Y4R agonist INS45973 significantly increased PPARγ expression. MRS 2279, a P2Y1R-specific antagonist, significantly modulated ATP-dependent PPARγ expression, whereas P2Y6R- (MRS2578), P2Y11R- (NF340), and P2Y12R- (ARC66096) specific antagonists did not modify the ATP-dependent effect on PPARγ expression (Fig. 6B). As expected, KN62, a P2X7R antagonist, did not affect ATP-dependent increase on PPARγ expression levels (not shown). Receptor antagonists added alone did not induce any effect at tested concentration (not shown). Furthermore, P2Y4R was upregulated during adipogenic differentiation, especially after ATP treatment (Supplementary Fig. S3A). Overall, these data demonstrate that ATP stimulated BM-hMSC adipogenic differentiation via P2YRs, preferentially through stimulation of the P2Y1R and P2Y4R subtypes.

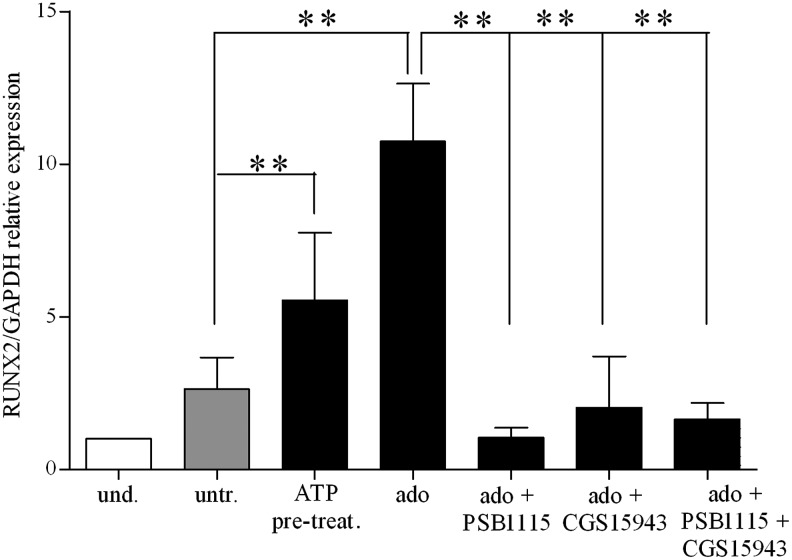

Signaling pathway of adenosine-stimulated osteogenic differentiation

Adenosine exerts its activity via P1 family receptors [32], which are expressed in BM-hMSCs [76]. We first confirmed that all four adenosine receptors, though to a different level, are expressed in BM-hMSCs. A P1 generic antagonist (CGS15943) added to adenosine-treated BM-hMSCs cultured under osteogenic conditions decreased RUNX2 expression levels as compared with adenosine alone confirming involvement of P1Rs in adenosine-dependent stimulation of osteogenesis (Fig. 7). A recently published article indicated A2B receptor as new regulator of osteoblast differentiation in a knockout mouse model [77]. We then demonstrated the expression of the A2B receptor in BM-hMSCs, and this receptor was upregulated upon ATP or adenosine treatment (Supplementary Fig. S3B). Then, we decided to test the A2B-specific antagonists PSB1115, and we found that adenosine failed to increase RUNX2 expression levels in the presence of PSB1115 (Fig. 7). These results suggested that, accordingly to the murine system, adenosine may increase osteogenic differentiation capacity of BM-hMSCs by stimulating the A2B receptor subtype.

FIG. 7.

Adenosine receptor stimulation during osteogenic differentiation of BM-hMSCs. qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression of RUNX2 (RUNX2/GAPDH relative levels) in undifferentiated (white histograms) (taken as 1) and differentiated cells (light gray and black histograms) at 3 weeks of differentiation in an osteogenic medium after incubation with adenosine alone (ado) or in combination with CGS15943, generic P1 receptor antagonist or PSB1115, A2B-specific receptor antagonist or both (mean±SD of 4 independent experiments), using untreated cells as the reference group, **P<0.01 for ATP-pretreatment and **P<0.001 for ado; not significant for the other conditions; using ado as the reference group **P<0.02 for ado+PSB1115; *P<0.01 for the other conditions (assigned value in undifferentiated cells was 1).

Discussion

Purinergic signaling is involved in several physiological pathways of cell biology, including regulation of proliferation, differentiation, migration, and cell death. A growing body of data has indicated that extracellular nucleotides might play an important role in bone and adipocytes cell biology [78–81]. However, little is known about the role of ATP and its metabolites during the lineage determination of human MSCs, bona fide precursors of bone cells and adipocytes.

The presence of nucleotides in the extracellular microenvironment is largely due to the balance between their release from cells and their degradation by sequential intervention of specialized ectoenzymes. Moreover, each cell type expresses a peculiar array of purine and pyrimidine receptors, modulated in different physiologic and pathological conditions. Thus, the ultimate effect of purine and pyrimidine signaling is determined by the concentration of active molecules and by the pattern of P1/P2 receptor expression and stimulation in target cells.

In this view, we previously demonstrated that BM-hMSCs expressed functional P2Rs whose engagement inhibited cell proliferation while enhanced in vitro and in vivo cell migration, as well as the release of proinflammatory cytokines [33].

In this work, we asked whether pharmacological stimulation with extracellular ATP may modulate the differentiation capacity of BM-hMSCs. Our microarray data showed that ATP treatment induced the expression of different key factors involved in osteoblastic and adipogenic differentiation of BM-hMSCs. ATP-dependent induction of differentiation-representative genes (ie, PPARγ and RUNX2) was confirmed by qRT-PCR. More specifically, we investigated the signaling cascades potentially involved. We demonstrated that ATP stimulated adipogenic differentiation, mainly acting through specific membrane purinoceptors such as P2Y1R and P2Y4R subtypes. Conversely, adenosine, resulting from ATP degradation by CD39 and CD73 ectoenzymes expressed on the BM-hMSC membrane, increased BM-hMSC osteogenic differentiation, by activating the A2B adenosine-specific receptor subtype.

Extracellular nucleotides are important modulators of bone cell biology. For example, bone injury induces the increase of extracellular ATP, which in turn acts as an autocrine or paracrine regulator of both osteoblast and osteoclast functions [78]. The differentiation of osteoblasts from their precursors MSCs is an important component of physiological bone homeostasis as well as bone repair after injury [82,83]. For this reason, we decide to analyze the molecular pathway activated by extracellular nucleotides during the MSC differentiation process. Of note, in our experiments, the effects of pretreatment with purines on BM-hMSC differentiation occur very rapidly (ie, within 24 h) and are maintained up to 3 weeks. Molecular analysis indicated that extracellular purines contributed to BM-hMSC differentiation at different levels. In osteogenic conditions, we found a consistent upregulation of factors promoting (1) osteogenic cell proliferation (ie, IL-18), (2) differentiation of preosteoblasts to osteoblast (ie, CAST), and mostly (3) terminal differentiation and bone matrix formation (ie, ROR2, SOX4, POSTN, and STC1). Concurrently, we observed the upregulation of genes inhibiting adipogenesis during osteogenic differentiation (ie, ADM). These data highlighted a key role of extracellular nucleotides during MSC differentiation and not only in already differentiated bone cells.

Furthermore, in this work, we pointed out the pivotal function of adenosine in stimulating BM-hMSC osteogenic differentiation. Indeed, although the pattern of adenosine receptors has been characterized in human osteoblast precursors [76], their involvement in lineage-specific differentiation from MSCs has not been described so far.

We found that osteogenic differentiation of BM-hMSCs was specifically induced by the nucleoside adenosine, rather than by ATP. Indeed, when ectonucleotidase activity (ie, CD39 and CD73) was inhibited, the effect of ATP on rising levels of RUNX2 was abolished. Consistently with our data, the knockout of the ectonucleotidase CD73 in mice decreases osteoblast differentiation, resulting in osteopenia [84]. We also extended to humans a recent report on murine cells showing that A2BKO mice showed impaired osteogenic differentiation [77].

We also demonstrated that ATP, in its triphosphate form, and not adenosine, stimulated adipogenic differentiation. ATP made BM-hMSCs more sensitive to adipogenic hormones even in proliferating nonconfluent cells (Fig. 3). We demonstrated that ATP specifically drives BM-hMSCs toward adipogenic differentiation. Furthermore, using selective receptor agonists and antagonists, we were able to identify the involvement of specific receptor subtypes, such as P2Y1R and P2Y4R, although we cannot rule out the involvement of other pathways. We demonstrated that unlike to what we observed in osteogenic differentiation, inhibition of CD73 potentiated the effect of ATP. Thus, degradation of ATP in adenosine switched off the BM-hMSC adipogenic differentiation. However, as P2Y1R was mainly activated by nucleotide diphosphates [26], we can speculate that the activity of nucleotides on adipogenic differentiation may be due to the cooperative action of ATP stimulating the P2Y4R receptor and ADP acting at the P2Y1R.

In this work, 1 mM ATP and 100 μM adenosine were used in the majority of the experiments as effective concentrations in potentiating MSC differentiation. High concentrations of ATP, ranging from 1 to 10 mM, are present in the cytoplasm of cells, whereas low concentration (1–10 nM) can be found in the extracellular space. Under pathological conditions, such as tissue injury, inflammatory reaction, hyperactivity, and tumor cell growth, ATP is rapidly released by dying cells, leading to massive increase in extracellular ATP and rapid formation of adenosine [21,22,85,86]. Also, adenosine concentrations in cells and tissue fluids are low (30–300 nM), but they rise substantially in different forms of cellular distress [21,22,30]. Thus, we mimic the concentrations that can be reached in the extracellular milieu in pathological conditions, where the regenerative capacity of MSCs is most needed. Furthermore, in this perspective, ATP- or adenosine-treatment, at tested concentrations, may serve as priming agents to modulate adipogenic/osteogenic differentiation for regenerative medicine applications and/or tissue engineering purposes.

In conclusion, with the present study, we provide new insights into molecular regulation of human MSC differentiation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by MIUR (PRIN 2008 and FIRB 2011), grants by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Scientific Research (MIUR), the National Research Council of Italy, the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC), the Italian Space Agency (ASI), and the University of Ferrara. Project Tecnopolo of Regione Emilia Romagna and AIRC project no. 12055, Special Program Molecular Clinical Oncology 5×1000 to AGIMM (AIRC-Gruppo Italiano Malattie Mieloproliferative), project no. 10005. R.Z. is supported by Regione Emilia-Romagna (Progetti di Ricerca Regione-Università).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:641–650. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horwitz EM. Le Blanc K. Dominici M. Mueller I. Slaper-Cortenbach I. Marini FC. Deans RJ. Krause DS. Keating A. Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:393–395. doi: 10.1080/14653240500319234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pittenger MF. Mackay AM. Beck SC. Jaiswal RK. Douglas R. Mosca JD. Moorman MA. Simonetti DW. Craig S. Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang Y. Jahagirdar BN. Reinhardt RL. Schwartz RE. Keene CD. Ortiz-Gonzalez XR. Reyes M. Lenvik T. Lund T, et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418:41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le Blanc K. Immunomodulatory effects of fetal and adult mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotherapy. 2003;5:485–489. doi: 10.1080/14653240310003611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krampera M. Glennie S. Dyson J. Scott D. Laylor R. Simpson E. Dazzi F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the response of naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to their cognate peptide. Blood. 2003;101:3722–3729. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fibbe WE. Nauta AJ. Roelofs H. Modulation of immune responses by mesenchymal stem cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1106:272–278. doi: 10.1196/annals.1392.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uccelli A. Moretta L. Pistoia V. Immunoregulatory function of mesenchymal stem cells. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2566–2573. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eliopoulos N. Stagg J. Lejeune L. Pommey S. Galipeau J. Allogeneic marrow stromal cells are immune rejected by MHC class I- and class II-mismatched recipient mice. Blood. 2005;106:4057–4065. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poncelet AJ. Vercruysse J. Saliez A. Gianello P. Although pig allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells are not immunogenic in vitro, intracardiac injection elicits an immune response in vivo. Transplantation. 2007;83:783–790. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000258649.23081.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isakova IA. Dufour J. Lanclos C. Bruhn J. Phinney DG. Cell-dose-dependent increases in circulating levels of immune effector cells in rhesus macaques following intracranial injection of allogeneic MSCs. Exp Hematol. 2010;38:957–967.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffin MD. Ritter T. Mahon BP. Immunological aspects of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell therapies. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21:1641–1655. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caplan AI. Adult mesenchymal stem cells for tissue engineering versus regenerative medicine. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:341–347. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lemoli RM. Bertolini F. Cancedda R. De Luca M. Del Santo A. Ferrari G. Ferrari S. Martino G. Mavilio F. Tura S. Stem cell plasticity: time for a reappraisal? Haematologica. 2005;90:360–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aluigi M. Fogli M. Curti A. Isidori A. Gruppioni E. Chiodoni C. Colombo MP. Versura P. D'Errico-Grigioni A, et al. Nucleofection is an efficient nonviral transfection technique for human bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:454–461. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sensebé L. Krampera M. Schrezenmeier H. Bourin P. Giordano R. Mesenchymal stem cells for clinical application. Vox Sang. 2010;98:93–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2009.01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryten M. Dunn PM. Neary JT. Burnstock G. ATP regulates the differentiation of mammalian skeletal muscle by activation of a P2X5 receptor on satellite cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:345–355. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sak K. Boeynaems JM. Everaus H. Involvement of P2Y receptors in the differentiation of haematopoietic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:442–447. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1102561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burnstock G. Historical review: ATP as a neurotransmitter. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gachet C. P2 receptors, platelet function and pharmacological implications. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:466–472. doi: 10.1160/TH07-11-0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bours MJ. Swennen EL. Di Virgilio F. Cronstein BN. Dagnelie PC. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate and adenosine as endogenous signaling molecules in immunity and inflammation. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112:358–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Virgilio F. Purines, purinergic receptors, and cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5441–5447. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burnstock G. Knight GE. Greig AV. Purinergic signaling in healthy and diseased skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:526–546. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ralevic V. Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbracchio MP. Burnstock G. Boeynaems JM. Barnard EA. Boyer JL. Kennedy C. Knight GE. Fumagalli M. Gachet C. Jacobson KA. Weisman GA. International Union of Pharmacology LVIII: update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: from molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:281–341. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burnstock G. Purine and pyrimidine receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1471–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6497-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmermann H. Extracellular metabolism of ATP and other nucleotides. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362:299–309. doi: 10.1007/s002100000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yegutkin GG. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:673–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shryock JC. Belardinelli L. Adenosine and adenosine receptors in the cardiovascular system: biochemistry, physiology, and pharmacology. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:2–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fredholm BB. Adenosine, an endogenous distress signal, modulates tissue damage and repair. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fredholm BB. Adenosine receptors as drug targets. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1284–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fredholm BB. IJzerman AP. Jacobson KA. Klotz KN. Linden J. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors—an update. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:1–34. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrari D. Gulinelli S. Salvestrini V. Lucchetti G. Zini R. Manfredini R. Caione L. Piacibello W. Ciciarello M, et al. Purinergic stimulation of human mesenchymal stem cells potentiates their chemotactic response to CXCL12 and increases the homing capacity and production of proinflammatory cytokines. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:360–374. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lemoli RM. Ferrari D. Fogli M. Rossi L. Pizzirani C. Forchap S. Chiozzi P. Vaselli D. Bertolini F, et al. Extracellular nucleotides are potent stimulators of human hematopoietic stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2004;104:1662–1670. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossi L. Manfredini R. Bertolini F. Ferrari D. Fogli M. Zini R. Salati S. Salvestrini V. Gulinelli S, et al. The extracellular nucleotide UTP is a potent inducer of hematopoietic stem cell migration. Blood. 2007;109:533–542. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-035634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salvestrini V. Zini R. Rossi L. Gulinelli S. Manfredini R. Bianchi E. Piacibello W. Caione L. Migliardi G, et al. Purinergic signaling inhibits human acute myeloblastic leukemia cell proliferation, migration, and engraftment in immunodeficient mice. Blood. 2012;119:217–226. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-370775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak KJ. Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otto F. Thornell AP. Crompton T. Denzel A. Gilmour KC. Rosewell IR. Stamp GW. Beddington RS. Mundlos S, et al. Cbfa1, a candidate gene for cleidocranial dysplasia syndrome, is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone development. Cell. 1997;89:765–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siqueira MF. Flowers S. Bhattacharya R. Faibish D. Behl Y. Kotton DN. Gerstenfeld L. Moran E. Graves DT. FOXO1 modulates osteoblast differentiation. Bone. 2011;48:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim HJ. Minashima T. McCarthy EF. Winkles JA. Kirsch T. Progressive ankylosis protein (ANK) in osteoblasts and osteoclasts controls bone formation and bone remodeling. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1771–1783. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Komori T. Regulation of bone development and extracellular matrix protein genes by RUNX2. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:189–195. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0832-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lavery K. Swain P. Falb D. Alaoui-Ismaili MH. BMP-2/4 and BMP-6/7 differentially utilize cell surface receptors to induce osteoblastic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20948–20958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800850200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Si W. Kang Q. Luu HH. Park JK. Luo Q. Song WX. Jiang W. Luo X. Li X, et al. CCN1/Cyr61 is regulated by the canonical Wnt signal and plays an important role in Wnt3A-induced osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2955–2964. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.2955-2964.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schedlich LJ. Muthukaruppan A. O'Han MK. Baxter RC. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 interacts with the vitamin D receptor and modulates the vitamin D response in osteoblasts. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2378–2390. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giustina A. Mazziotti G. Canalis E. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factors, and the skeleton. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:535–559. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farmer SR. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang BH. Li L. Paul A. Taniguchi S. Nannegari V. Heird WC. Chan L. Protection against fatty liver but normal adipogenesis in mice lacking adipose differentiation-related protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1063–1076. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.1063-1076.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang J. Xia WL. Ahmad F. Regulation of pyruvate carboxylase in 3T3-L1 cells. Biochem J. 1995;306:205–210. doi: 10.1042/bj3060205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eastman SW. Yassaee M. Bieniasz PD. A role for ubiquitin ligases and Spartin/SPG20 in lipid droplet turnover. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:881–894. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jacques C. Recklies AD. Levy A. Berenbaum F. HC-gp39 contributes to chondrocyte differentiation by inducing SOX9 and type II collagen expressions. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baldridge D. Lennington J. Weis M. Homan EP. Jiang MM. Munivez E. Keene DR. Hogue WR. Pyott S, et al. Generalized connective tissue disease in Crtap-/- mouse. PLos One. 2010;5:e10560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Combs TP. Wagner JA. Berger J. Doebber T. Wang WJ. Zhang BB. Tanen M. Berg AH. O'Rahilly S, et al. Induction of adipocyte complement-related protein of 30 kilodaltons by PPARgamma agonists: a potential mechanism of insulin sensitization. Endocrinology. 2002;143:998–1007. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.3.8662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park SK. Oh SY. Lee MY. Yoon S. Kim KS. Kim JW. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein and nuclear factor-Y regulate adiponectin gene expression in adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2004;53:2757–2766. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.11.2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wellner M. Herse F. Janke J. Gorzelniak K. Engeli S. Bechart D. Lasalle P. Luft FC. Sharma AM. Endothelial cell specific molecule-1—a newly identified protein in adipocytes. Horm Metab Res. 2003;35:217–221. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonçalves CA. Leite MC. Guerra MC. Adipocytes as an important source of serum S100B and possible roles of this protein in adipose tissue. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2010;2010:790431. doi: 10.1155/2010/790431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moldes M. Lasnier F. Fève B. Pairault J. Djian P. Id3 prevents differentiation of preadipose cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1796–1804. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boland GM. Perkins G. Hall DJ. Tuan RS. Wnt 3a promotes proliferation and suppresses osteogenic differentiation of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2004;93:1210–1230. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rajalin AM. Aarnisalo P. Cross-talk between NR4A orphan nuclear receptors and β-catenin signaling pathway in osteoblasts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;509:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan TF. Couchourel D. Abed E. Delalandre A. Duval N. Lajeunesse D. Elevated Dickkopf-2 levels contribute to the abnormal phenotype of human osteoarthritic osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1399–1410. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yao W. Cheng Z. Shahnazari M. Dai W. Johnson ML. Lane NE. Overexpression of secreted frizzled-related protein 1 inhibits bone formation and attenuates parathyroid hormone bone anabolic effects. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:190–199. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cho HY. Choi HJ. Sun HJ, et al. Transgenic mice overexpressing secreted frizzled-related proteins (sFRP)4 under the control of serum amyloid P promoter exhibit low bone mass but did not result in disturbed phosphate homeostasis. Bone. 2010;47:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murray SS. Grisanti MS. Bentley GV. Kahn AJ. Urist MR. Murray EJ. The calpain-calpastatin system and cellular proliferation and differentiation in rodent osteoblastic cells. Exp Cell Res. 1997;233:297–309. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ouyang X. Fujimoto M. Nakagawa R. Serada S. Tanaka T. Nomura S. Kawase I. Kishimoto T. Naka T. SOCS-2 interferes with myotube formation and potentiates osteoblast differentiation through upregulation of JunB in C2C12 cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207:428–436. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoshiko Y. Maeda N. Aubin JE. Stanniocalcin 1 stimulates osteoblast differentiation in rat calvaria cell cultures. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4134–4143. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cornish J. Gillespie MT. Callon KE. Horwood NJ. Moseley JM. Reid IR. Interleukin-18 is a novel mitogen of osteogenic and chondrogenic cells. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1194–1201. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gordon JA. Hassan MQ. Koss M. Montecino M. Selleri L. van Wijnen AJ. Stein JL. Stein GS. Lian JB. Epigenetic regulation of early osteogenesis and mineralized tissue formation by a HOXA10-PBX1-associated complex. Cells Tissues Organs. 2011;194:146–150. doi: 10.1159/000324790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fortunati D. Reppe S. Fjeldheim AK. Nielsen M. Gautvik VT. Gautvik KM. Periostin is a collagen associated bone matrix protein regulated by parathyroid hormone. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Billiard J. Moran RA. Whitley MZ. Chatterjee-Kishore M. Gillis K. Brown EL. Komm BS. Bodine PV. Transcriptional profiling of human osteoblast differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:389–400. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Billiard J. Way DS. Seestaller-Wehr LM. Moran RA. Mangine A. Bodine PV. The orphan receptor tyrosine kinase Ror2 modulates canonical Wnt signaling in osteoblastic cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:90–101. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nistala H. Lee-Arteaga S. Smaldone S. Siciliano G. Carta L. Ono RN. Sengle G. Arteaga-Solis E. Levasseur R, et al. Fibrillin-1 and -2 differentially modulate endogenous TGF-β and BMP bioavailability during bone formation. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:1107–1121. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Spiegelman BM. Hu E. Kim JB. Brun R. PPAR gamma and the control of adipogenesis. Biochimie. 1997;79:111–112. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(97)81500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sattler C. Steinsdoerfer M. Offers M. Fischer E. Schierl R. Heseler K. Däubener W. Seissler J. Inhibition of T cell proliferation by murine multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells is mediated by CD39 expression and adenosine generation. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:1221–1230. doi: 10.3727/096368910X546553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saldanha-Araujo F. Ferreira FI. Palma PV. Araujo AG. Queiroz RH. Covas DT. Zago MA. Panepucci RA. Mesenchymal stromal cells upregulate CD39 and increase adenosine production to suppress activated T-lymphocytes. Stem Cell Res. 2011;7:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sundin M. D'arcy P. Johansson CC. Barrett AJ. Lönnies H. Sundberg B. Nava S. Kiessling R. Mougiakakos D. Le Blanc K. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells express FoxP3: a marker for the immunosuppressive capacity? J Immunother. 2011;34:336–342. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318217007c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murayama T. Katada T. Ui M. Guanine nucleotide activation and inhibition of adenylate cyclase as modified by islet-activating protein, pertussis toxin, in mouse 3T3 fibroblasts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;221:381–390. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Evans BA. Elford C. Pexa A. Francis K. Hughes AC. Deussen A. Ham J. Human osteoblast precursors produce extracellular adenosine, which modulates their secretion of IL-6 and osteoprotegerin. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:228–236. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carroll SH. Wigner NA. Kulkarni N. Johnston-Cox H. Gerstenfeld LC. Ravid K. A2B adenosine receptor promotes mesenchymal stem cell differentiation to osteoblasts and bone formation in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:15718–15727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.344994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Orriss IR. Burnstock G. Arnett TR. Purinergic signalling and bone remodelling. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vassaux G. Gaillard D. Mari B. Ailhaud G. Negrel R. Differential expression of adenosine A1 and A2 receptors in preadipocytes and adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193:1123–1130. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Børglum JD. Vassaux G. Richelsen B. Gaillard D. Darimont C. Ailhaud G. Negrel R. Changes in adenosine A1- and A2-receptor expression during adipose cell differentiation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;117:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(95)03728-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Omatsu-Kanbe M. Inoue K. Fujii Y. Yamamoto T. Isono T. Fujita N. Matsuura H. Effect of ATP on preadipocyte migration and adipocyte differentiation by activating P2Y receptors in 3T3-L1 cells. Biochem J. 2006;393:171–180. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Krampera M. Pizzolo G. Aprili G. Franchini M. Mesenchymal stem cells for bone, cartilage, tendon and skeletal muscle repair. Bone. 2006;39:678–683. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shapiro F. Bone development and its relation to fracture repair. The role of mesenchymal osteoblasts and surface osteoblasts. Eur Cell Mater. 2008;15:53–76. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v015a05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Takedachi M. Oohara H. Smith BJ. Iyama M. Kobashi M. Maeda K. Long CL. Humphrey MB. Stoecker BJ, et al. CD73-generated adenosine promotes osteoblast differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:2622–2631. doi: 10.1002/jcp.23001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Trabanelli S. Ocadlíková D. Gulinelli S. Curti A. Salvestrini V. de Paula Vieira R. Idzko M. Di Virgilio F. Ferrari D. Lemoli RM. Extracellular ATP exerts opposite effects on activated and regulatory CD4+ T cells via purinergic P2 receptor activation. J Immunol. 2012;189:1303–1310. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pellegatti P. Raffaghello L. Bianchi G. Piccardi F. Pistoia V. Di Virgilio F. Increased level of extracellular ATP at tumor sites: in vivo imaging with plasma membrane luciferase. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.