Abstract

Objective:

Different methods for contouring target volumes are currently in use in the UK when irradiating glioblastomas post operatively. Both one- and two-phase techniques are offered at different centres. 90% of relapses are recognised to occur locally when using radiotherapy alone. The objective of this evaluation was to determine the pattern of relapse following concomitant radiotherapy with temozolomide (RT-TMZ).

Methods:

A retrospective analysis of patients receiving RT-TMZ between 2006 and 2010 was performed. Outcome data including survival were calculated from the start of radiotherapy. Analysis of available serial cross-sectional imaging was performed from diagnosis to first relapse. The site of first relapse was defined by the relationship to primary disease. Central relapse was defined as progression of the primary enhancing mass or the appearance of a new enhancing nodule within 2 cm.

Results:

105 patients were identified as receiving RT-TMZ. 34 patients were not eligible for relapse analysis owing to either lack of progression or unsuitable imaging. Patterns of first relapse were as follows: 55 (77%) patients relapsed centrally within 2 cm of the original gadolinium-enhanced mass on MRI, 13 (18%) patients relapsed >4 cm from the original enhancement and 3 (4%) relapsed within the contralateral hemisphere.

Conclusion:

Central relapse remains the predominant pattern of failure following RT-TMZ. Single-phase conformal radiotherapy using a 2-cm margin from the original contrast-enhanced mass is appropriate for the majority of these patients.

Advances in knowledge:

Central relapse remains the predominant pattern of failure following chemoradiotherapy for glioblastomas.

In the UK, high-grade gliomas have an incidence of approximately 7.7 per 100 000 individuals per year, resulting in around 4800 new cases per year [1]. The current standard treatment for good performance status patients with glioblastomas is maximal safe resection followed by chemoradiotherapy, then 6 months of adjuvant chemotherapy using temozolomide (RT-TMZ). This approach was defined by the pivotal European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer/National Cancer Institute of Canada (EORTC/NCIC) randomised study first published by Stupp et al in 2005 [2,3]. The addition of temozolomide to radiotherapy, 60 Gy in 30 fractions, improved overall survival at 1 year from 10.9% to 27.2% and this survival advantage was maintained at 5 years [1.9% vs 9.8% (p<0.0001)].

Although RT-TMZ has become standard practice, radiotherapy delivery and target delineation variations still exist. Historically, large field radiotherapy was based on post-mortem studies confirming tumour cells within the oedema surrounding the contrast-enhanced mass as defined by CT [4]. A margin of ≥3 cm beyond oedema is required to ensure complete coverage of all tumour cells based on the post-mortem studies [5]. A two-phase technique was commonly used to achieve this and a study analysing pattern recurrence recommended a boost volume using a 4-cm field edge from the contrast-enhanced mass defined on CT [6]. Subsequent Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) guidelines specified a two-phase approach which incorporated oedema with a 2-cm margin in the first phase and subsequent boost to residual disease with a margin [7,8] (RTOG 0525 and 0825 trials). However, the studies carried out by Stupp et al [2,3] defined modern-day practice and 60 Gy in 30 fractions was delivered in a single phase. The protocol recommended a planning target volume (PTV) of 2–3 cm from the enhancing tumour or the tumour bed. This is based on several published series suggesting that the majority of relapses occur within 2 cm of the original tumour edge, indicating that it may be unnecessary to include peritumoral oedema to reduce the risk of future relapse [9,10].

Reducing the volume of brain exposed to radiotherapy could help to minimise toxicity and preserve quality of life. Through high-quality image fusion, improved dosimetry and more accurate treatment delivery many institutions have adapted protocols to permit reduction of the dose given to normal tissue [11–13]. The aim of this study was to evaluate the pattern of relapse following RT-TMZ using conformal radiotherapy to aid the development of a protocol using image-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT).

Methods and materials

All patients receiving RT-TMZ at University Hospital Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, between May 2006 and May 2010 were identified. Patients were eligible if they had histologically confirmed glioblastomas and provided informed consent for radical concomitant chemoradiotherapy using a 6-week fractionation schedule. Data collected included demographics, performance status, details of surgery and clinical outcome. The type of resection was classified according to the surgeon performing the operation as biopsy or partial or complete resection. A review of diagnostic imaging, radiotherapy plan and imaging post chemoradiotherapy was performed. All patients were immobilised using a thermoplastic shell and the gross tumour volume (GTV) was contoured using CT planning. All patients underwent CT scanning for radiotherapy planning using ProSoma® (MedCom GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). Target volumes were then defined by the treating clinician and, using the XiO® treatment planning system (Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden), the physics team produced the optimal plan. This was approved by the treating clinician. All patients were treated with 6-MV photons delivered using a linear accelerator. Portal imaging was performed as a minimum on Days 1, 2 and 3 and weekly thereafter, as per the local protocol. From October 2008, baseline (pre-surgical) T1 gadolinium-enhanced MRI was fused and a single clinical target volume (CTV) was created using a geometric margin of 1.5–2 cm from contrast-enhanced disease to produce the CTV60 with some adjustment to include any oedema visible on the planning CT scan. This was edited according to anatomical barriers including the midline except within the region of the corpus callosum. Patients with secondary glioblastomas had additional fusion of a T2 weighted MRI scan and a minimum margin of 1.5 cm for CTV. An isotropic margin of 0.5 cm was added to produce the PTV. Dose constraints for the optic pathways and brain stem were <55 Gy. If this was not possible owing to the proximity of the GTV, or if the volume was deemed large (typically more than one-third of the brain), 55 Gy in 30 fractions was the prescribed dose. During the early part of the study, standard follow-up consisted of a post-treatment MRI scan within 3 months of completion of RT-TMZ and at least every 6 months thereafter depending on the clinical need. During the early part of the study, standard follow-up consisted of a post-treatment MRI scan within 3 months of completion of RT-TMZ and at least every 6 months thereafter depending on the clinical need.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the site of first relapse in relation to the enhancing tumour as defined by pre-surgical T1 plus gadolinium MRI scan. All sequential MRI scans were reviewed by two neuroradiologists (one consultant and one neuroradiology fellow). Relapses were classified as central if there was progression of the residual tumour enhancement, or as distant if relapse occurred >4 cm from the original tumour edge (in either the ipsilateral or the contralateral hemisphere, or both). In the case of multiple lesions at the time of relapse the lesion furthest from the original enhancing tumour was used to define the pattern of relapse.

For unclear cases, categorised as marginal, where there was new ipsilateral enhancement between 2 and 4 cm, the MRI scan at the time of relapse (T1 with gadolinium) was coregistered with the radiotherapy plan. This was reviewed by a neuroradiologist and a clinical oncologist to assess whether the relapse occurred centrally within the 95% isodose or was truly beyond 2 cm. These were then categorised appropriately as central or marginal relapses. All relapses occurring within the ipsilateral hemisphere but >4 cm from the edge of the original tumour were reviewed to assess the percentage occurring as a result of subependymal spread.

Secondary outcomes included time to progression and overall survival rates.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival was calculated from the start of radiotherapy until death, or for living patients until the date they were last seen. Progression-free survival was defined as the time from the start of therapy until progression of disease or death. Living and non-relapsed patients were censored at the date they were last seen alive and free of progression. Kaplan–Meier survival estimates were calculated and log–rank statistics were used to compare across prognostic factors. All analyses were performed using SAS® v. 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics

105 patients who consented for RT-TMZ were identified between May 2006 and May 2010. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. All patients at the time of first review in the clinic were offered a radical course of radiotherapy (60 Gy in 30 fractions) with concomitant temozolomide.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics

| Characteristic | Patients, n (%) |

| Median age at diagnosis (range), years | 55 (18–69) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 68 (64.8) |

| Female | 37 (35.2) |

| WHO performance status prior to CRT | |

| 0 | 40 (38.1) |

| 1 | 54 (51.4) |

| Unknown | 11 (10.5) |

| Neurosurgery | |

| Biopsy alone | 19 (18.1) |

| Partial resection | 76 (72.4) |

| Complete resection | 10 (9.5) |

| Dose/fractionation received (Gy) | |

| 55/30 fractions | 53 (50.5) |

| 60/30 fractions | 52 (49.5) |

| Concurrent temozolomide 6 weeks completed | |

| Yes | 91 (86.6) |

| No | 14 (13.3) |

| Adjuvant temozolomide 6 months completed | |

| Yes | 86 (81.9) |

| No | 19 (18.1) |

CRT, conformal radiotherapy; WHO, World Health Organization.

Patient outcomes

At the time of analysis, 25 patients were alive and 80 had died. The median follow-up in surviving patients was 23.2 months [range 13–55 months; interquartile range (IQR) 16–29 months]. The 1-, 2- and 3-year survival rates were 63.8%, 31.8% and 17.6%, respectively. The median overall survival was 14.3 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 12.2–16.5 months]. The 1-, 2- and 3-year progression-free survival rates were 35.2%, 18.4% and 7.9%, respectively. The median progression-free survival was 8.9 months (95% CI 7.5–10.6 months).

Patterns of relapse

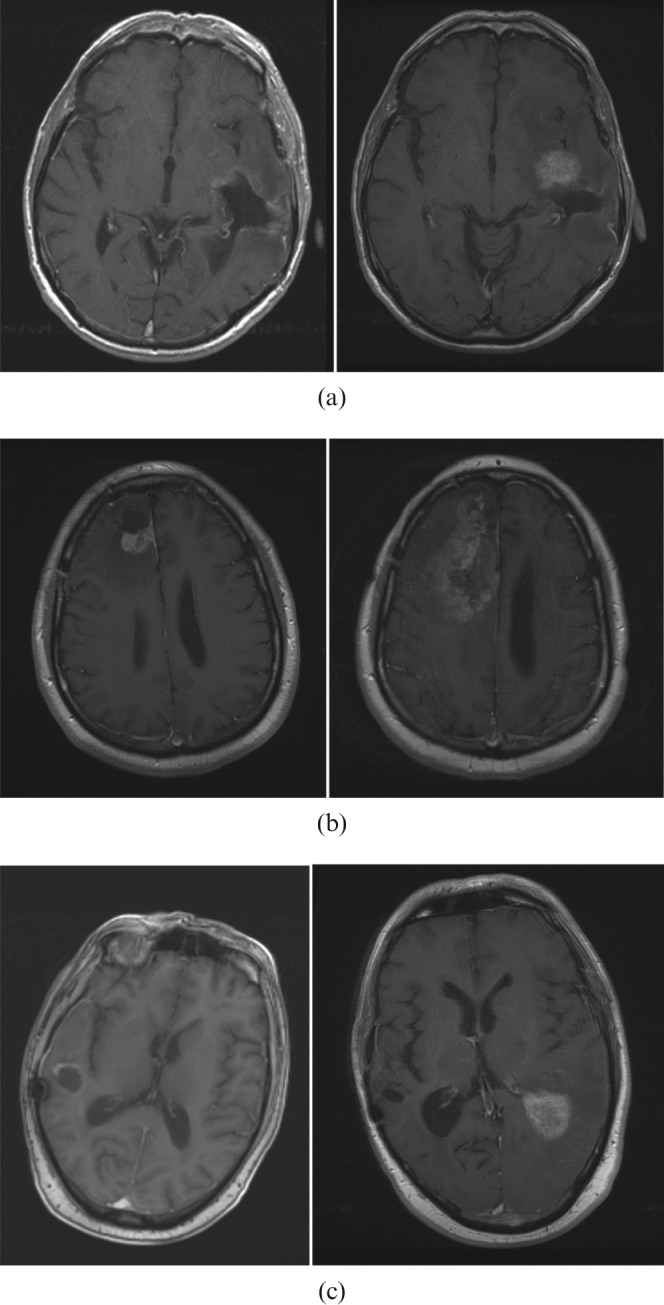

71 patients developed intracranial relapses identified on MRI. Table 2 illustrates the patterns of relapse observed in our cohort and the timing of these relapses. Figure 1a–c compares examples of post-operative MRI (T1 with gadolinium) with the MR images (T1 with gadolinium) at the time of relapse.

Table 2.

Patterns of relapse

| Site of first relapse | Number of patients | Median (range) time to relapse, months |

| Central (within 2 cm of tumour edge) | 55 | 8 (0–30) |

| Marginal (2.1–4.0 cm from tumour edge) | 0 | – |

| Distant: ipsilateral hemisphere (>4 cm from tumour edge) | 13 | 9 (3–23) |

| Distant: contralateral hemisphere (>4 cm from tumour edge) | 3 | 15 (4–27) |

| Stable disease or response on imaging | 22 | – |

| Unknown (no appropriate imaging available) | 12 | – |

Figure 1.

(a) Central relapse: post-surgery MRI (left); MRI at the time of relapse (right). (b) Ipsilateral distant relapse: post-surgery MRI (left); MRI at the time of relapse (right). (c) Contralateral distant relapse: post-surgery MRI (left); MRI at the time of relapse (right).

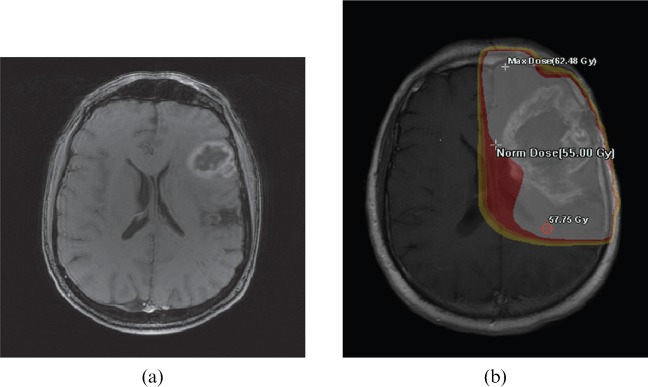

The most commonly occurring site of first relapse was central, occurring in 55 patients. This included the 13 patients identified as having marginal relapse. For the marginal group, the MRI scan at the time of relapse was coregistered with the radiotherapy plan and in all cases the relapse was confirmed to be within the prescribed high-dose volume. Figure 2 shows an example of this comparing the baseline MRI at diagnosis with the coregistered MRI at relapse and radiotherapy isodoses. 16 patients had distant relapses: 13 within the ipsilateral hemisphere, >4 cm from the original tumour, and 3 within the contralateral hemisphere.

Figure 2.

Example of a baseline MRI at diagnosis (a) compared with the coregistered MRI at the time of first relapse and the radiotherapy isodoses (b). Max, maximum; Norm, normal.

22 patients were not analysed because they had either stable disease or a response to treatment at the time of the last imaging. One patient was excluded because the last available imaging suggested pseudoprogression, with no further imaging to clarify this. For the additional 12 patients, no imaging was available to assess the site of relapse owing to rapid clinical deterioration and subsequent death.

The central relapses occurred earlier than the distant (both ipsilateral and contralateral) relapses: the median time to relapse for the central relapses was 8 months (range 0–30 months) compared with 9 months (range 3–23 months) for the ipsilateral distant relapses and 15 months (range 4–27 months) for the contralateral distant relapses. The overall median time to relapse was 8 months (range 0–30 months; IQR 5–11 months). Of the 13 patients developing ipsilateral distant relapses, 10 were identified as showing subependymal spread on imaging.

Treatment compliance

Of the 105 patients, 101 completed the intended radiotherapy schedule without gaps; 4 patients had delays in the middle of treatment but all subsequently restarted and completed the radiotherapy schedule. Of these, one patient suffered a myocardial infarction during radiotherapy and therefore had a gap while this was managed; one patient deteriorated neurologically within the first week of treatment—MRI confirmed disease progression and therefore treatment was delayed and replanned to a larger volume; one patient developed pancytopenia as a consequence of temozolomide—radiotherapy was delayed while the patient recovered and was subsequently restarted without concomitant temozolomide; and one patient developed pneumonia and radiotherapy was therefore delayed while this was treated.

91 patients of the 105 completed 42 days of concomitant RT-TMZ on schedule. The remaining patients (14 of the 105) did not complete the course and had a median duration of temozolomide of 28 days (range 7–30 days). Of these, 10 patients subsequently developed central relapse, 1 developed ipsilateral distant relapse, 1 had stable disease at the time of the last follow-up and 2 did not have imaging to assess the site of the relapse. There was no correlation between failure to complete temozolomide on schedule and subsequent central relapse (χ2=1.346, p=0.246). Of the 14 who failed to complete chemotherapy, 5 developed at least grade 2 thrombocytopaenia, 4 developed fatigue, 2 developed myelosuppression, 2 developed infections (pneumonia and cellulitis) requiring intravenous antibiotics and 1 patient developed abnormal liver function tests.

19 of the 105 patients did not receive any adjuvant temozolomide post RT-TMZ. For the majority of these, this was because of reduced performance status (15) or persistent myelosuppression (2). One patient left the UK after completion of RT-TMZ and the remaining patient had persistent abnormal liver function tests so chemotherapy was never recommenced. Of those patients who received adjuvant temozolomide, 22 continued treatment beyond 6 months, with a median time of 10 months (range 7–26 months).

Discussion

This study confirmed that the majority of first glioblastoma relapses following RT-TMZ occurred close to the original contrast-enhanced mass. The overall survival in this sequential cohort of patients was similar to that seen in the prospective study by Stupp et al [2,3] and reports by other individual institutions using different approaches to contouring [11,12,14,15].

Data on the patterns of relapse of glioblastomas following RT-TMZ using a range of contouring methods are summarised in Table 3 [12–15]. In concordance with the other studies, this study suggests that the addition of temozolomide to radiotherapy does not alter the fact that the majority of first relapses occur close to the original enhancing disease [12–15].

Table 3. Comparison with the literature.

| Study | Number of patients with recurrence confirmed on imaging | Dose/fractionation (Gy/number of fractions) | Planning technique | Site of first local relapse | Number (%) |

| Present study | 71 | 55–60/30 | Conformal (see text) | Central (≤2 cm from baseline tumour) | 55 (77.5) |

| GTV+1.5–2 cm=CTV | Marginal (2.1–4.0 cm from baseline tumour) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| CTV+0.5 cm=PTV | Distant (>4 cm from baseline tumour) | 16 (22.5) | |||

| Minniti et al [12] | 105 | 60/30 | Conformal | Central/in-field (>95% within 95% isodose curve) | 85 (81.0) |

| Post-operative tumour cavity and residual tumour GTV+2 cm to CTV+0.3 cm to PTV | Marginal | 6 (5.7) | |||

| Distant (outside the 20% isodose line) | 14 (13.3) | ||||

| McDonald et al [13] | 41 | 60/30 | IMRT (90%) | Central/in-field | 38 (93) |

| (46/23 Phase 1; 14/7 Phase 2) | Conformal (10%) | Marginal | 2 (5) | ||

| Phase 1: post-operative GTV (T2 or FLAIR MR sequences)+0.5 cm to CTV+0.5 cm to PTV | Distant | 1 (2) | |||

| Phase 2: residual T1 enhancing tumour and resection cavity+0.5 cm to CTV+0.5 cm to PTV | |||||

| Brandes et al [14] | 79 | 60/30 | Conformal | Within field | 57 (72.2) |

| Pre-operative GTV+2–3 cm=CTV | Marginal | 5 (6.3) | |||

| Outside field | 17 (21.5) | ||||

| Milano et al [15] | 39 | 60/30 to tumour+2–2.5 cm margin | Conformal | Within field (within 95% isodose curve) | 36 (92) |

| Oedema+2 cm received 46–50 Gy in 2 Gy per fraction | Marginal (crosses 95% isodose curve) | 6 (15) | |||

| Distant (completely outside 95% isodose curve) | 5 (13) |

CTV, clinical target volume; FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion–recovery; GTV, gross tumour volume; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiotherapy; PTV, planning target volume.

It is possible that single-dose approaches miss the low-volume tumour cells that lie at some distance from the enhancing central tumour volume. McDonald et al [13] analysed 62 consecutive patients treated with 60 Gy and concurrent temozolomide (97%) or arsenic (3%) using 2 dose volumes. The majority of failures occurred close to the original enhancing disease. Central failure occurred in 78% of patients. In-field relapse was defined if 80% of the relapse occurred within the 60-Gy isodose line and occurred in 15% of patients. The low-dose CTV was created by adding a margin to the T2 fluid-attenuated inversion–recovery volume and the margin varied from 0.5 to 1.0 cm. The dose varied according to technique: 46 Gy in 23 fractions for sequential treatment and 54 Gy in 30 fractions for synchronous integrated boost (77%). The 60-Gy CTV was defined by adding a margin to the gadolinium-enhanced mass which varied from 0 to 1 cm. A PTV of 3–5 mm was added to the boost. Distant relapse, defined as <20% of the volume of relapse inside the 60-Gy isodose line, was reported in 2% of patients in this cohort, and marginal relapse, defined as between 20% and 80% of the volume of relapse inside the 60-Gy isodose line, occurred in the remaining 5%. The contouring technique used in this study was compared with the two-phase RTOG technique and revealed significantly smaller volumes of normal brain irradiated without an apparent increase in marginal failure.

Milano et al [15] reported patterns of relapse in 54 patients following 60 Gy in 30 fractions with temozolomide. A range of radiotherapy techniques were used, including IMRT. A two-phase technique was used throughout. During the first phase, 46–50 Gy was delivered to the oedema plus 2 cm, and for the second phase 60 Gy was delivered to the enhancing tumour/tumour bed plus 2.0–2.5 cm. Although not specified, these volumes are assumed to describe the PTVs. Central relapse, defined as progression of the original enhancement or within the post-operative bed, occurred in 31 of 38 patients (82%), although this was not always the site of the first relapse or the only site of relapse. Patterns of first relapse in the form of a new, discrete enhancing lesion were also analysed: 92% developed in-field relapse, defined as a new lesion entirely within the 95% isodose line; 15% developed marginal relapse, defined as a new lesion crossing the 95% isodose line; and 13% developed distant relapse, defined as a new lesion entirely outside of the 95% isodose line.

Minniti et al [12] compared relapse patterns in 105 patients planned using the EORTC technique of GTV encompassing the resection cavity and any residual tumour seen on post-operative T1 weighted MRI with a 2-cm margin to create the CTV prior to adding a 3-mm PTV. After relapse was confirmed, the patients were retrospectively replanned using the two-phase RTOG technique and comparison was made as to radiation coverage of the site of subsequent recurrence with each contouring technique. The results revealed a significantly greater volume of normal brain tissue irradiated using the RTOG two-phase technique; however, no significant difference in the relationship of the site of relapse to the irradiated volume was identified between the two techniques.

Chang et al [11] concluded that inclusion of the oedema had no effect on the site of relapse. No differences were observed in the patterns of relapse between the RTOG two-phase (including all the oedema) and the EORTC single-phase (excluding oedema) techniques when plans were reconstructed. 48 radiotherapy plans were considered and comparison was made between the sites of relapse and compared with a retrospectively planned RTOG two-phase technique. The volume of oedema (Ve) and the volume of recurrence (Vrec) were compared and the overlap region, the volume of intersection (Vint), was considered. No statistically significant correlation was identified between the Vrec and the Ve (p=0.3). 90% of patients had central or in-field relapse regardless of whether the one- or two-phase technique was considered. Of the remaining 10% of patients, all the sites of marginal and distant relapse failed to be covered by the Phase 1 CTV using the larger two-phase RTOG technique.

For the study presented here, the marginal cases were fused to the radiotherapy plan to ensure that truly marginal relapses were accurately identified. However, a distance-based evaluation rather than a volume-based technique was used. Lee et al [16], in the pre-concomitant chemotherapy era, considered the percentage of the relapsed volume that was within the volume receiving 95% of the prescribed dose (D95). This percentage was used to define central (95% of the volume of recurrence within the D95), in-field (80% of the volume of recurrence within the D95), marginal (20–80% within the D95) and outside (<20% within the D95) relapses. It remains unclear as to whether one method of recurrence evaluation is superior to the other. The results of Lee et al, however, remain consistent with those of other studies using the distance from the enhancing tumour, in that the majority of relapses occur centrally.

No survival differences have been identified between the EORTC single-phase and the RTOG two-phase techniques. The two-phase technique no doubt reduces the risk of missing disease and permits radiotherapy to microscopic tumour cells known to exist in both the surrounding oedema and the non-enhancing brain tissue beyond, albeit at a lower dose [4,5]. However, in the era of high-quality MRI, coregistration and more accurate three-dimensional treatment planning, the benefits of large field radiotherapy are less clear, particularly given that the predominant pattern of failure is central. In addition, irradiating large volumes of normal brain tissue could be associated with a higher incidence of late neurocognitive effects and a reduction in quality of life [17]. Furthermore, in this analysis a significant proportion of the ipsilateral failures occurred as a result of subependymal spread, a recognised pattern of failure [9], rather than distant parenchyma disease that would be targeted by a two-phase approach. This indicates that tumours close to ventricles need to be planned with this in mind: it may be better to extend a treatment volume along the ependymal region for a longer distance, while sparing some of the full 2-cm margin if this extends more deeply into the ventricle.

Consistent with other studies, the central and in-field relapses had a tendency to occur earlier and it has been hypothesised that this may be a manifestation of patients with more treatment-sensitive disease being vulnerable to later metastatic or distant spread [14,15]. Brandes et al [14] confirmed that patients with O6-methylguanine-deoxyribonucleic acid methyltransferase methylation developed fewer recurrences in or close to the radiotherapy treatment field [14]. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) gene mutations also have a better prognosis than the wild-type tumours; however, data are presently unavailable as to whether such tumours have different patterns of recurrence [18]. We acknowledge that a limitation of this analysis is the lack of any molecular information. Study into patterns of relapse considering molecular variations could allow for a more individualised or risk-based approach to radiotherapy planning.

Another issue might be underdosage of a superficially situated glioblastoma using 6-MV photons: the electronic build-up through scalp and skull will reach 100% of the dose from lateral beams at a depth of around 1.5 cm, which could result in underdosage of part of a tumour closer than this. Planning software systems may not be highly reliable in the build-up region. The tumour shown in Figure 2 would be an example of this potential problem.

High-grade gliomas that had transformed from low-grade gliomas were included in this study, with consideration given to the T2 alongside the T1 weighted MRI. It is acknowledged that these potentially require a different approach to encompass the low-grade tumour. There is a need to improve imaging techniques to more accurately delineate high- and low-grade tumours. Dose escalation up to 80–90 Gy to improve local control has proven possible with the use of proton irradiation; however, tumours continued to recur peripherally with an increase in the number of patients developing radiation necrosis and progressive neurological deterioration. The dose escalation had little impact on survival, with the patients dying of more distant relapse [19].

Consistent with the trial by Stupp et al [2,3], most would recommend a minimum dose of 60 Gy to the tumour or tumour bed. In this study a significant proportion of patients received 55 Gy in 30 fractions. A review of UK clinical practice confirmed that such an approach is common practice [20]. A common reason for such dose reduction was to permit single-phase or non-segmented treatment to tumours in close proximity to the optic pathways, deep mid-brain structures and/or brain stem, or for larger tumours in older patients. The recent quantitative analysis of normal tissue effects in the clinic publications predict the incidence of radiation-induced optic neuropathy to be 3–7% for doses of 55–60 Gy [21] and suggest that small volumes of the brain stem (1–10 cm3) may be irradiated to doses of 60 Gy with acceptable risks of toxicity [22]. With increased access to IMRT it will be easier to deliver 60 Gy while keeping conventional dose constraints to critical organs at risk [23]. It is more difficult to quantify the correlation between the volume of brain irradiated to a high dose and quality of life or other parameters such as cognitive function. However, such end points are increasingly important for subsets of patients who have a more favourable prognosis.

The retrospective nature of this study no doubt contributed to heterogeneity in the population; pseudoprogression is now a well-recognised cause of early local failure on imaging and is commonly managed with ongoing therapy and sequential imaging [24]. Unfortunately, owing to the inconsistent early post-treatment imaging protocol across this cohort, accurate information on pseudoprogression is not available and this is acknowledged as a further limitation. Current standard practice is to perform a baseline scan 4–6 weeks following RT-TMZ, and then 3-monthly. Brain necrosis is another cause of similar imaging appearances. It is also acknowledged that the T2 weighted MRI scan was not routinely fused with the planning data set for all cases. With improved resources it is now standard practice locally to include the T2 weighted fusion.

Further prospective data on relapse patterns may be made available from prospective randomised control trials; however, heterogeneity in contouring and dose prescription are confounding variables. All prospective clinical trials evaluating new agents for glioblastomas should now have strict quality assurance for the radiotherapy prescription. This should include timing and quality of diagnostic imaging, contouring technique, immobilisation and on-treatment imaging verification. Although the optimum radiotherapy contouring technique remains debated, permitting variations may influence interpretation of data. It is accepted that delineating the tumour bed can be difficult post resection; however, uncertainty can be reduced using multiple image coregistration including an early post-operative MRI scan. This study supports the use of 55–60 Gy to a CTV of 2 cm beyond residual disease or surgical cavity to minimise the risk of marginal relapse, but greater care in planning periventricular tumours, very superficial tumours and transformed tumours is required.

Conclusion

Central relapse remains the predominant pattern of failure following RT-TMZ. Single-phase conformal radiotherapy using a 2-cm margin from the original contrast-enhanced mass is appropriate for the majority of these patients.

References

- 1.Counsell CE, Collie DA, Grant R. Incidence of intracranial tumours in the Lothian region of Scotland, 1989–90. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;61:143–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Mason WP, Van denBent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005;352:987–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, Van denBent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomized phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:459–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burger PC, Dubois PJ, Schold C, Smith KR, Odum GL, Crafts DC, et al. Computerized tomographic and pathologic studies of the untreated, quiescent, and recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurosurg 1983;58:159–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halperin EC, Bentel G, Heinz ER, Burger PC. Radiation therapy treatment planning in supratentorial glioblastoma multiforme: an analysis based on post mortem topographic anatomy with CT correlations. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1989;17:1347–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gasper LE, Fisher BJ, MacDonald DR, Leber DV, Halperin EC, Schold SC, et al. Supratentorial malignant glioma: patterns of recurrence and implications for external beam local treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1992;24:55–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert MR, Wang M, Aldape KD, Stupp R, Hegi M, Jaeckle KA, et al. RTOG 0525: a randomized phase III trial comparing standard adjuvant temozolomide (TMZ) with a dose dense (dd) schedule in newly diagnosed glioblastoma (GBM). J Clin Oncol 2011;29(Suppl.; abstr 2006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.rtog. org [homepage on the internet] Philadelphia, PA: Radiation Therapy Oncology Group; 2011. [cited 12 February 2012]. Available from: http://www.rtog.org/ClinicalTrials/ProtocolTable/StudyDetails.aspx?action=openFile&FileID=4664. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochberg FH, Pruitt A. Assumptions in the radiotherapy of glioblastoma. Neurology 1980;30:907–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallner KE, Galicich JH, Krol G, Arbit E, Malkin MG. Patterns of failure following treatment for glioblastoma multiforme and anaplastic astrocytoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1989;16:1405–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang EL, Akyurek S, Avalos T, Rebueno N, Spicer C, Garcia J, et al. Evaluation of peritumoral edema in the delineation of radiotherapy clinical target volumes for glioblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007;68:144–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minniti G, Amelio D, Amichetti M, Salvati M, Muni R, Bozzao A, et al. Patterns of failure and comparison of different target volume delineations in patients with glioblastoma treated with conformal radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide. Radiother Oncol 2010;97:377–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald MW, Shu HG, Curran WJ, Crocker IR. Pattern of failure after limited margin radiotherapy and temozolomide for glioblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;79:130–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Fransceschi E, Sotti G, Frezza G, Amista P, et al. Recurrence pattern after temozolomide concomitant with and adjuvant to radiotherapy in newly diagnosed patients with glioblastoma: correlation with MGMT promoter methylation status. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1275–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milano MT, Okunieff P, Donatello RS, Mohile MA, Sul J, Walter KA, et al. Patterns and timing of recurrence after temozolomide-based chemoradiation for glioblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;8:1147–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SW, Fraass BA, Marsh LH, Herbort K, Gebarski SS, Martel MK, et al. Patterns of failure following high-dose 3-D conformal radiotherapy for high-grade astrocytomas: a quantitative dosimetric study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999;43:79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence YR, Li XA, El Naqa I, Hahn CA, Marks LB, Merchant TE, et al. Radiation dose–volume effects in the brain. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;76(Suppl. 3):S20–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan H, Williams Parsons D, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med 2009;360:765–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzek MM, Thornton AF, Rabinov JD, Lev MH, Pardo FS, Munzenrider JE, et al. Accelerated fractionated proton/photon irradiation to 90 cobalt gray equivalent for glioblastoma multiforme: results of a phase II prospective trial. J Neurosurg 1999;91:251–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Creak AL, Tree A, Saran F. Radiotherapy planning in high-grade gliomas: a survey of current UK practice. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2011;23:189–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayo C, Martel MK, Marks LB, Flickinger J, Nam J, Kirkpatrick J. Radiation dose–volume effects of optic nerves and chiasm. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;76Suppl. 3:S28–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayo C, Yorke E, Merchant TE. Radiation associated brainstem injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;76Suppl. 3:S36–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davidson MTM, Masucci GL, Follwell M, Blake SJ, Xu W, Moseley DJ, et al. Single arc volumetric modulated arc therapy for complex brain gliomas: is there an advantage as compared to intensity modulated radiotherapy or by adding a partial arc? Technol Cancer Res Treat 2012;11:211–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanghera P, Rampling R, Haylock B, Jefferies S, McBain C, Rees JH, et al. The concepts, diagnosis and management of early imaging changes after therapy for glioblastomas. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2012;24:216–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]