Abstract

Volumetric-modulated arc therapy (VMAT) is increasingly popular as a treatment method in radiotherapy owing to the speed with which treatments can be delivered. However, there has been little investigation into the effect of increased modulation in lung plans with regard to interfraction organ motion. This is most likely to occur where the planning target volume (PTV) lies within areas of low density. This paper aims to investigate the effect of modulation on the dose distribution using simulated patient movement and to propose a method that is less susceptible to such movement. Simulated interfraction motion is achieved by moving the plan isocentre in steps of 0.5 cm and 1.0 cm in six directions for five clinical VMAT patients. The proposed planning method involves optimisation using a density override of 1 g cm−3, within the PTV in lung, to reduce segment boosting in the periphery of the PTV. This investigation shows that modulation can result in an increase in the maximum dose of >25%, an increase in PTV near-maximum dose of 17% and a reduction in near-minimum dose by 46%. Unacceptable organ at risk (OAR) doses are also seen. The proposed method reduces modulation, resulting in a maximum dose increase of 10%. Although safeguards are in place to prevent the increased dose to OARs from patient movement, there is nothing to prevent the increased dose as a result of modulation in lung. A simple planning method is proposed to safeguard against this effect. Investigation suggests that, where modulation exists in a plan, this method reduces it and is clinically viable.

Volumetric-modulated arc therapy (VMAT) is becoming increasingly popular as a treatment method in radiotherapy owing to the speed with which treatments can be delivered [1, 2] and the benefit to dose distribution. This benefit is clear in patients with concave planning target volumes (PTVs) near organs at risk (OARs) [1, 3]. Several studies have compared VMAT with intensity-modulated radiotherapy and conventional plans for lung cancer with a favourable outcome [4–7]. Although there have been recent investigations into the effect of breathing motion [8] and the interplay effect, there has been little investigation into the effect of interfraction internal patient movement [9, 10] on the dose distribution.

Where part of the PTV comprises air or low-density tissue (i.e. lung), the optimiser attempts to boost the dose to these regions to attain coverage with the 95% isodose line despite the lack of tissue providing scatter. This can result in highly modulated plans. This “boosting” effect occurs owing to a lack of the scatter material present in the beam and results in horns in the fluence profile. The effect also occurs in situations where any PTV is positioned near the patient’s skin [11,p. 56–58].

The boosting effect is undesirable for two reasons. Firstly, it is unnecessary to produce the same dose to the PTV in air as the PTV in tumour tissue. As long as the PTV in air is being exposed to the same fluence as the PTV in tissue, then the tumour grows or moves into a region of air, the higher dose will follow it. However, if the plan is modulated to boost the dose to the PTV in air, then organ movement causes a deviation from the planning CT geometry, very high doses can be seen in regions where tissue falls within a boosted part of the beam. This may occur in lung patients as the tumour regresses or owing to atelectasis. In situations where daily imaging and breath-hold devices or gating are not used, consideration should be given as to whether it is appropriate to deliver modulated VMAT plans for lung patients.

There are three options for avoiding unwanted modulation in air in an optimised VMAT plan. Firstly, an edited PTV can be used for optimising, which does not extend fully into the lung, thus preventing the need for any dose boosting in the lung. Alternatively, a bolus on the skin surface can be used to provide scatter in order to increase the dose to the skin region without boosting. However, this is not applicable in the lung. A third alternative is to optimise using a fake bolus, providing the scatter material to prevent boosting, and then to remove the bolus for the final dose calculation of the clinical plan. This results in poorer peripheral coverage near the skin surface or in the lung, compared with using a real bolus, but allows for patient movement within the fake bolus region without any dose boosting. In conformal plans, this could be achieved by pulling back multileaf collimators (MLCs) or jaws.

This paper aims to investigate the effect of patient movement on the dose distribution for the clinical plan of five patients treated with a single VMAT arc. An alternative method of planning is proposed using a density override of the PTV in lung to 1 g cm−3 (i.e. a fake bolus) to reduce the boosting effect. This method is investigated to determine whether it increases the safety of modulated arc therapy in the case of internal organ movement and uncertainties in patient set-up.

METHODS

Commonly, lung patients at our centre are planned using in-house software (Autobeam [2]) that produces a conformal arc. However, in cases where the PTV is situated adjacent to or overlapping with the spinal cord or other OAR, SmartArc (Pinnacle3 v. 9.0; Philips Radiation Oncology Systems, Fitchburg, WI) is used to meet the clinical objectives as it allows a more modulated beam. This can result in increased modulation to boost the dose to the PTV in lung. Single-arc SmartArc plans were therefore used in this study.

Plans were optimised using SmartArc with leaf motion constrained to 0.8 cm per degree. Patients were scanned and treated using the active breathing coordinator [12] device and were also imaged using cone-beam CT (CBCT) for the first three fractions and then weekly thereafter. In this study, five clinical patient plans were reviewed. The location and size of the PTV for each patient can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Size and position of the planning target volume (PTV) for each patient. Prescription is to the mean of the PTV

| Patient | PTV (ml) | PTV location | PTV in lung (%) | Prescription (Gy) |

| 1 | 273 | Superior right post | 33 | 60 |

| 2 | 297 | Medial/left post | 34 | 64 |

| 3 | 252 | Superior left post | 47 | 64 |

| 4 | 266 | Superior right post | 27 | 60 |

| 5 | 342 | Superior left post | 30 | 64 |

Post, posterior.

Assessing the robustness of VMAT for lung

Patient movement was simulated using an isocentre-shift method with shifts of 0.5 cm and 1 cm in the anterior–posterior, superior–inferior and left–right directions. The availability of CBCT online correction makes this an unlikely clinical scenario but the method is sufficient to simulate the effect of internal structure movement that is less easily corrected for [12]. Each clinical plan was then applied to the shifted isocentres by fixing the monitor units and recalculating. Plans were calculated on a rectangular dose grid of 0.25 cm resolution using the Pinnacle adaptive convolution algorithm. The PTV D2, D98 and D50 and maximum point dose in the plan were recorded for each shift and for the original clinical plan to determine the impact of the change in anatomy. The lung V20, lung mean dose and spinal cord maximum dose were also recorded.

PTV D2 and D98 are the near-maximum and near-minimum doses, respectively, reported in accordance with recommendations made in International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements (ICRU) report 83 [11], along with the median absorbed dose, PTV D50. Lung V20 is the volume of lung minus gross tumour volume (GTV) that receives 20 Gy.

Proposed planning method

The boosting effect occurs as the beam is modulated to provide dosimetric coverage by the 95% isodose of the PTV in lung. The proposed solution involved creating a new region of interest comprising the PTV within lung (i.e. within very low-density tissue) and overriding the density of this region to 1 g cm−3. The plans were optimised with the prescription to the mean of the PTV with this density override on. Plans were considered clinically acceptable when the OAR constraints were met. The time for delivery was limited to the minimum allowed for the gantry to do a full rotation (68 s) to limit MLC movement. The density override was then removed for the final dose calculation. Each plan was subsequently represcribed to the PTV in tissue (defined as the PTV–PTV in lung), labelled PTVp. The same isocentre-shift method was then used to assess the impact of interfraction motion.

RESULTS

Assessing the robustness of VMAT for lung

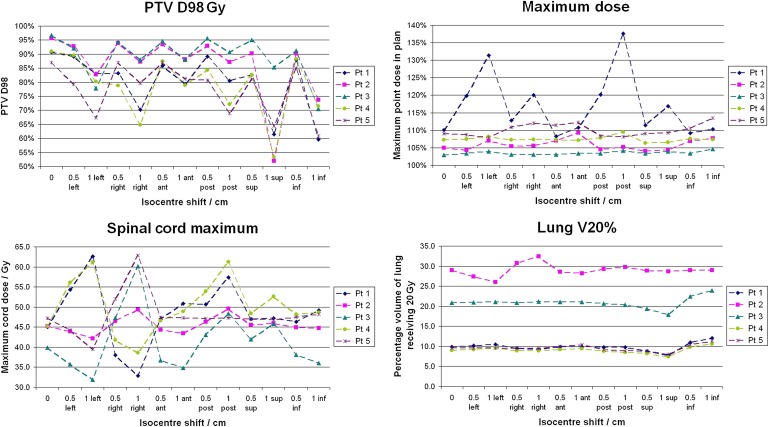

The maximum point dose in the plan, as a percentage of the prescribed dose, is shown for each isocentre-shift plan in Figure 1, along with the PTV D98, lung V20 and spinal cord maximum dose. The results vary considerably between patients. The graph for Patient 1 demonstrates dose boosting up to 138% of the prescribed dose (i.e. 82.6 Gy, an increase from the clinical plan maximum dose of 16.5 Gy) with a 1-cm shift. The graph for Patient 3 shows no boosting whatsoever as the maximum dose remains almost constant at 103% of the prescribed dose.

Figure 1.

Effect of patient movement on the planning target volume (PTV) D98, maximum delivered dose, lung V20 and spinal cord maximum dose. Lines are to guide the eye; they are not intended to indicate a trend. ant, anterior; inf, inferior; post, posterior; pt, patient; sup, superior.

As could be expected, shifting the isocentre results in poorer coverage of the PTV as shown in the D98 graph. The worst case for most patients was a 1-cm shift inferiorly, resulting in a D98 of <55% of the prescribed dose for two of the patients, compared with >90% for both clinical plans. The cord maximum dose and lung V20 are very dependent on the position of the PTV. The tumour for Patient 2 was located in the middle of the left lung resulting in a higher V20. However, this was not greatly affected by isocentre shifts, whereas the cord dose rose as high as 63 Gy.

Proposed planning method

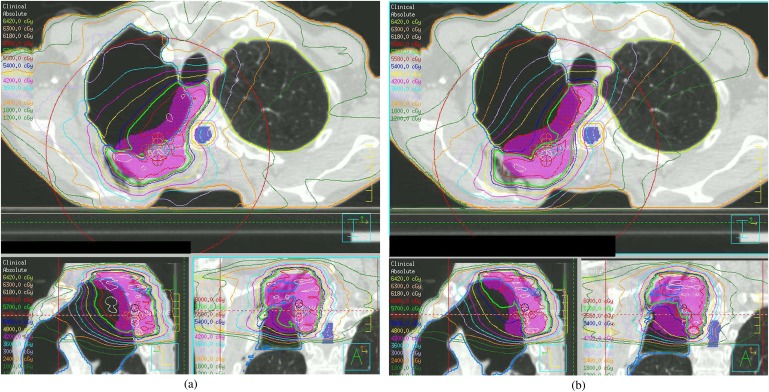

The dose distribution for the clinical plan produced using the proposed planning method was compared with the original plan (Figure 2). Represcribing to the mean of the PTV in tissue once the density override was removed resulted in a reduction in monitor units of on average 0.4% (−0.57% to −0.24%) compared with the optimised plan. In each case, the final clinical plan was clinically acceptable. It was possible to keep all OAR doses within constraints even with the reduced delivery time. Table 2 demonstrates the dose to normal tissues for the new method.

Figure 2.

Original clinical plan for Patient 1 (a), and the proposed new plan with density override switched off (b). Bold isodose represents 95% of the prescribed dose.

Table 2.

Dose to organs at risk for both the original clinical plan and the proposed new planning method for five patients

| Patient no. | Maximum spinal cord | Mean lung dose | Lung V20 | |||

| Clinical plan (Gy) | New plan (Gy) | Clinical plan (Gy) | New plan (Gy) | Clinical plan (%) | New plan (%) | |

| 1 | 45.05 | 45.20 | 5.65 | 5.30 | 10 | 9 |

| 2 | 45.21 | 44.83 | 16.80 | 17.22 | 29 | 29 |

| 3 | 39.88 | 43.83 | 11.92 | 12.38 | 21 | 22 |

| 4 | 45.23 | 45.74 | 6.67 | 6.87 | 9 | 10 |

| 5 | 47.25 | 45.38 | 6.38 | 6.60 | 10 | 10 |

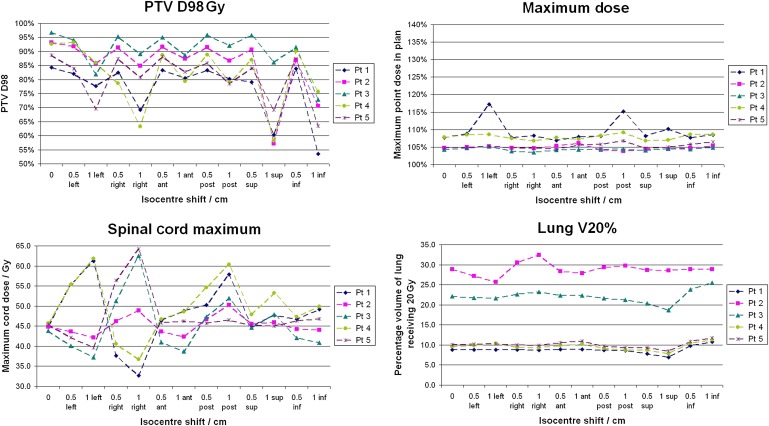

Figure 3 shows the variation in the maximum percentage dose for the isocentre-shifted plans for the proposed planning method. There is a general improvement in the amount of variation in the maximum dose compared with the original planning method. There is a marked improvement in the dose boosting for Patient 1 compared with the original plan, with the maximum dose now 115% of the prescribed dose. An improvement is also seen for Patient 2. The new method produced a higher dose for the clinical plan of Patient 3. However, there is no high dose above 105% of the prescribed dose for any of the shifts. The results for Patient 4 showed no difference in the maximum dose between the planning methods. The clinical plan for Patient 5 was actually improved using the new planning method as a hotspot was removed and the maximum point dose dropped from 109% to 105%. Figure 3 shows that there was also less of an increase when the plan was shifted, as the new plan was less modulated than the original clinical plan.

Figure 3.

Effect of patient movement on the planning target volume (PTV) D98, maximum delivered dose, lung V20 and spinal cord maximum dose for the proposed planning method. Lines are to guide the eye; they are not intended to indicate a trend. Same scale as in Figure 1. ant, anterior; inf, inferior; post, posterior; pt, patient; sup, superior.

There is no substantial difference between the variation in the cord dose, lung V20 and PTV D98 for the original and proposed plans. However, the D98 is lower for the proposed clinical plans. The dose distribution was not expected to cover the PTV in lung with the 95% isodose owing to the lack of dense tissue; however, if the GTV had moved within this region, the 95% isodose would follow it while it remained within the PTV. This is because the GTV is relatively dense tissue.

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to determine the effect of modulation on the dose distribution in the case of internal anatomical movement. There was some variation in the amount of modulation of the plans and the resultant boosting effect that was seen. This is to be expected owing to the varying size and shape of the lung tumour and the PTV and its location within the lung as well as the amount of lung within the PTV.

Clearly, patient movement should be minimised or taken into account during delivery as far as is reasonably possible. This study demonstrated unacceptable OAR doses for some patients when isocentre shifts were applied, particularly in the cases where the PTV was situated adjacent to the spinal cord. This is to be expected as large shifts of 0.5 cm and 1 cm were used. A planning OAR volume is used during planning to account for uncertainties in positioning. CBCT is also used and registration is to bony landmarks, specifically the spinal canal. The PTV should account for this uncertainty in set-up and movement around the clinical target volume [11]. However, none of these methods can completely account for anatomical changes. Consequently, a planning method is proposed to improve the robustness of VMAT for lung patients.

The proposed method is similar to the fake bolus method discussed in ICRU report 83 [11]. Optimising to the tumour tissue volume would not allow for dosimetric coverage if the tissue moved within the PTV in lung, and a real bolus is not a realistic option within the lung. The proposed method is to override the density of the PTV in lung (PTVp) during optimisation. This method resulted in a more stable dose distribution during organ movement and was simple to implement with very little additional planning time required. The proposed method produced a higher dose in the new plan for Patient 3 than the original clinical plan because the plan was optimised with a density override in place. This highlights the lack of control in the final plan as the optimising is done before the density override is removed. However, this resulted in a very small increase in the dose that was consistent across all isocentre shifts showing no dose boosting. Therefore, if a plan is clinically acceptable, then this is not an issue.

As a result of reviewing these five patients, this method could be clinically implemented as a more robust VMAT plan. However, lung patients requiring a SmartArc plan at our centre are relatively rare. In the case of such a patient, it is suggested that the plan with the density override on is also reviewed by the clinician to ensure that the expected coverage in the case of GTV movement within the PTV is good. This study addresses the issue of modulation in SmartArc plans only. It would be worthwhile investigating this effect in other planning systems as well and potentially extending the implementation of the proposed method.

CONCLUSION

This paper investigates the effect of modulation on the dose distribution in lung SmartArc plans by using simulated patient movement. Shifting the isocentre to simulate organ motion gives on average a 2% increase in the maximum dose. The largest increase in the maximum point dose is 28%. Lung V20 varies by 0% on average, with a maximum increase of 2% (from 10% to 12%). The maximum cord dose increases up to 63 Gy with an average maximum dose of 46.2 Gy.

A new method has been devised to reduce the possibility of delivering an unknown high dose in the event of internal patient movement and the results seen using the isocentre-shift method suggest that it is effective. The maximum cord dose is 64.2 Gy with an average of 47.3 Gy. This increase in the cord dose is likely to be a result of moving the high-dose volume towards the spinal cord rather than any boosting of the dose resulting from changes to the modulation in the PTV. The lung V20 mean variation is 0% with a maximum increase of 2% (from 9% to 11%). The mean increase in the maximum dose over all five patients is reduced to 0.5%. The largest increase in the maximum point dose is reduced to 10% for the proposed new planning method.

There is a general reduction in the amount of modulation where modulation exists in the original plan. In those patients in whom there is little MLC leaf motion, there is no benefit of using this method. This new method is simple to implement and does not require additional planning time.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ma L, Yu CX, Earl M, Holmes T, Sarfaraz M, Li XA, et al. Optimized intensity-modulated arc therapy for prostate cancer treatment. Int J Cancer 2001;96:379–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedford JL. Treatment planning for volumetric modulated arc therapy. Med Phys 2009;36:5128–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fogliata A, Clivio A, Nicolini G, Vanetti E, Cozzi L. A treatment planning study using non-coplanar static fields and coplanar arcs for whole breast radiotherapy of patients with concave geometry. Radiother Oncol 2007;85:346–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedford JL, Hansen VN, McNair HA, Aitken AH, Brock JEC, Warrington AP, et al. Treatment of lung cancer using volumetric modulated arc therapy and image guidance: a case study. Acta Oncol 2008;47:1438–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holt A, Vliet-Vroegindeweij CV, Mans A, Belderbos JS, Damen EM. Volumetric-modulated arc therapy for stereotactic body radiotherapy of lung tumours: a comparison with intensity-modulated radiotherapy techniques. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;81:1560–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang X, Li T, Liu Y, Zhou L, Xu Y, Zhou X, et al. Planning analysis for locally advanced lung cancer: dosimetric and efficiency comparisons between intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), single-arc/partial-arc volumetric modulated arc therapy (SA/PA-VMAT). Radiat Oncol 2011;6:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brock J, Bedford J, Partridge M, McDonald F, Ashley S, McNair H, et al. Optimising stereotactic body radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer with volumetric intensity-modulated arc therapy—a planning study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2012;24:68–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao M, Wu J, Cao D, Wong T, Mehta V, Shepard D, et al. Dosimetric impact of breathing motion in lung stereotactic body radiotherapy treatment using image-modulated radiotherapy and volumetric modulated arc therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;83:251–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knap MM, Hoffmann L, Nordsmark M, Vestergaard A. Daily cone-beam computed tomography used to determine tumour shrinkage and localisation in lung cancer patients. Acta Oncol 2010;49:1077–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim G, Bezjak A, Higgins J, Moseley D, Hope AJ, Sun A, et al. Tumour regression and positional changes in non-small cell lung cancer during radical radiotherapy. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:531–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements ICRU report 83: prescribing, recording, and reporting photon-beam intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). J ICRU 2010;10:41–58 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brock J, McNair HA, Panakis N, Symonds-Tayler R, Evans PM, Brada M. The use of the active breathing coordinator throughout radical non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;81:369–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]