Abstract

Mental stress (MS) and changes in posture can both be associated with cardiovascular dysfunction. The purpose of this study was to determine neurovascular responses to MS in the supine and upright postures. MS was elicited in 17 subjects (26 ± 1 y) by 5 min of mental arithmetic. Doppler ultrasound was used to measure peak blood velocity in the renal (RBFV) and superior mesenteric arteries (SMBFV). Leg blood flow (LBF) was measured using Doppler ultrasound and forearm blood flow (FBF) was measured using plethysmography. Microneurography was used to measure muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA; n = 5) in the leg. At rest, heart rate and MSNA were significantly greater whereas LBF, FBF, RBFV, and SMBFV and their respective conductances were significantly less in the upright compared to supine posture. MS elicited similar increases in mean arterial pressure (~12 mmHg) and heart rate (~17 beats/min) regardless of posture. MS in both postures elicited a decrease in RBFV, SMBFV, and their conductances and an increase in LBF, FBF, and their conductances. Changes in blood flow were blunted in the upright posture in all vascular beds examined, but the pattern of the vascular response was the same as the supine posture. MS did not elicit changes in MSNA in either the supine or upright posture (~ Δ 2 ± 2 bursts/min and ~ Δ 1 ± 2 bursts/min, respectively). In conclusion, the augmented sympathetic activity of the upright posture does not alter heart rate, mean arterial pressure, or MSNA responses to MS. MS elicits a divergent vascular response in the visceral and peripheral vasculature. These results indicate that although the upright posture attenuates vascular responses to MS, the pattern of neurovascular responses does not differ between postures.

Keywords: visceral blood flow, sympathetic, orthostatic, vascular conductance, renal, forearm

Introduction

Mental stress is reportedly linked to a variety of cardiovascular disorders. For example, mental stress is associated with development of myocardial ischemia (Deanfield et al., 1984; Smith & Little, 1992; Krantz et al., 1996), hypertension (Yan et al., 2003) and endothelial dysfunction (Ghiadoni et al., 2000; Spieker et al., 2002). The vast majority of studies investigating the physiological responses to mental stress have been performed in the supine posture. However, humans often experience mental stress in conjunction with an orthostatic challenge. Similar to mental stress, maintaining the upright posture is associated with a variety of pathological conditions and it is estimated that 1 to 6 % of emergency room visits a year are related to orthostasis (Sun et al., 2005). The upright posture has been linked to the same physiological phenomena as mental stress including the development of myocardial ischemia (Smith & Little, 1992; Krantz et al., 1996), changes in endothelial function (Guazzi et al., 2004; Guazzi et al., 2005), and abnormal blood pressures (Robertson & Davis, 1995; Fessel & Robertson, 2006). Currently, little is known about how mental stress and the upright posture interact with respect to cardiovascular hemodynamics. An understanding of this interaction is important because both stressors occur together and are linked to similar cardiovascular events.

The cardiovascular responses to mental stress in the supine posture and the upright posture have similarities and differences. Cardiovascular responses to mental stress in the supine posture include: 1) increases in heart rate, blood pressure, and forearm blood flow (FBF) (Blair et al., 1959; Brod et al., 1959; Halliwill et al., 1997), 2) vasoconstriction in the visceral arteries (Tidgren & Hjemdahl, 1989; Hayashi et al., 2006) 3) and increases or no change in muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) (Anderson et al., 1987; Carter et al., 2005b). The physiological responses to the upright posture include increases in heart rate, vasoconstriction in the limbs and viscera, and increases in sympathetic outflow (Rowell et al., 1972; Wallin & Sundlof, 1982; Kitano et al., 2005). How cardiovascular hemodynamics will be altered by the combined challenge of the upright posture and mental stress and how these responses will be regulated remains unclear.

An understanding of the pattern of responses to combined mental stress and orthostatic challenge is important because it has been speculated that vasodilation in the forearm elicited by mental stress may compromise cerebral perfusion and contribute to syncope (Roddie, 1977; Carter et al., 2005a) even though increases in FBF are blunted during combined mental stress and orthostatic challenge (Rusch et al., 1981; Hamer et al., 2003). Therefore, the current study was designed to examine if posture influences neurovascular responses to mental stress. We compared renal artery, superior mesenteric artery, forearm, and leg blood flow during mental stress in the supine and upright postures. Furthermore, MSNA responses to mental stress in the supine and upright postures were examined. It was hypothesized that the upright posture would diminish neurovascular responses to mental stress because of elevated resting MSNA, total peripheral resistance, and heart rate, but that the pattern of the responses would remain the same.

Methods

Seventeen volunteers (7 females and 10 males; age 26 ± 1 year; height 175 ± 3 cm; weight 73 ± 4 kg; BMI, 24 ± 1 kg/m2) participated in the study. All subjects were normotensive, non-obese, non-smokers, not taking any medications, and had no autonomic dysfunction or cardiovascular diseases. Subjects arrived at the laboratory fasted and having abstained from caffeine, alcohol, and exercise for 12 hours. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine and all subjects gave written informed consent before the study.

Experimental Protocol

Renal and superior mesenteric artery peak blood velocities (RBFV and SMBFV, respectively) and FBF and leg blood flow (LBF) were recorded in the supine and upright postures during mental stress. During the upright trials subjects were tilted to 80° degrees. The order of the supine and upright trials was counterbalanced for all trials. A 5-min baseline was recorded in each respective posture followed by 5 min of mental stress and a 5-min recovery. A supine rest period separated each trial and the next trial began when heart rate and mean arterial pressure returned to baseline. RBFV was recorded in eight subjects and SMBFV was recorded in nine subjects. RBFV and SMBFV were recorded on the same laboratory visit. The order of renal and superior mesenteric artery trials in the same subject was counterbalanced. FBF was recorded during all RBFV and SMBFV trials.

LBF was recorded in nine subjects on a different day from the RBFV and SMBFV trials. Leg MSNA responses were measured in five subjects during mental stress in both postures on a separate day from the blood flow trials. A 3-min baseline was recorded in each posture, followed by 5 min of mental stress and a 3-min recovery. Subjects rested in the supine position between each trial and the second trial did not begin until blood pressure and heart rate returned to baseline.

Mental stress was elicited by mental arithmetic. During mental stress, subjects repeatedly subtracted the number six or seven from a two or three digit number. Subjects answered verbally and were encouraged by the investigators to subtract as fast as possible. An investigator provided a new number to subtract from every 5–10 s. The subtraction number, six or seven, was randomized. Subjects were asked to rate perceived stress following mental stress using a standard five-point scale of 0 (not stressful), 1 (somewhat stressful), 2 (stressful), 3 (very stressful), and 4 (very, very stressful) (Carter et al., 2002). Subject perceived stress levels were recorded after each mental stress trial.

Measurements

Duplex ultrasound (HDI 5000, ATL Ultrasound, Bothell, WA, USA) was used to measure RBFV and SMBFV. The renal and superior mesenteric arteries were scanned using the anterior abdominal approach while the subject was lying supine or during head-up tilt. To scan the arteries a curved-array transducer (2–5 MHz) with a 2.5-MHz pulsed Doppler frequency was used. The probe insonation angle to each artery was less than 60°. The focal zone was set at the depth of the target artery. The transducer was held in the same place to record velocity tracings during each trial; therefore, the data were obtained in the same phase of the respiratory cycle. Each cardiac cycle Doppler tracing was analyzed using the software of the ATL machine to obtain RBFV and SMBFV measurements. A minimum of five heartbeats was averaged for each minute of the whole experimental protocol. The ratio of blood flow velocity and mean arterial pressure was used as an index of renal and superior mesenteric artery conductance.

FBF was measured using venous occlusion plethysmography (Hokanson, Bellevue, WA, USA). Mercury-in-silastic strain gauges were placed around the maximal circumference of the forearm. The arm was positioned above the heart in the upright and supine postures. Wrist cuffs were inflated to 220 mmHg to arrest circulation to the hand. Blood flow was determined every 15 sec. The ratio of FBF and mean arterial pressure was used as an index of forearm vascular conductance.

LBF was measured with high resolution Doppler ultrasound. A 5–12 MHz transducer with a 6 MHz pulsed Doppler frequency was positioned over the common femoral artery. The insonation angle for measuring mean blood velocity was 60°. To minimize overestimation of mean blood velocity the sample volume was maximized. To measure arterial diameter a longitudinal view of the artery was taken. Arterial diameter measurements were taken at the end of diastole (determined by ECG) by measuring the distance between near and far wall intima–media. Vessel diameter and blood velocity were averaged from a minimum of 5 heartbeats each minute of the experimental protocol. Arterial blood flow was calculated by multiplying the cross sectional area (πr2) of the vessel by the mean blood velocity and by 60. The ratio of LBF and mean arterial pressure was used as an index of leg vascular conductance.

Multifiber recordings of MSNA were measured directly by inserting a tungsten microelectrode into the peroneal nerve posterior to the fibular head. A reference electrode was inserted subcutaneously 2–3 cm from the recording electrode. Both electrodes were connected to a differential preamplifier and then to an amplifier where the nerve signal was band-pass filtered (700–2000 Hz) and integrated at a time constant of 0.1 s to obtain a mean voltage display of nerve activity. Satisfactory recordings of MSNA were defined by spontaneous, pulse-synchronous bursts that did not change during arousal or stroking of the skin.

Heart rate and blood pressure was continuously recorded during all trials using a Finometer (Finapres Medical Systems, Amsterdam, Netherlands). During the RBFV and SMBFV trials, when FBF and the finometer were recorded simultaneously, we recorded ankle blood pressures (Dinamap, General Electrics, Waukesha, WI, USA). To compare ankle blood pressures when subjects were supine and upright we height corrected the upright blood pressures by multiplying the distance between the suprastrenal notch and the blood pressure cuff by 0.75 and then subtracted this number from the upright pressures. During the femoral and MSNA trials blood pressure was recorded at the brachial artery.

Data analysis

Sympathetic bursts were identified from inspection of mean voltage neurograms displayed by a computer program (Peaks; ADInstruments). MSNA was expressed as burst frequency and total activity (the sum of individual burst area expressed in arbitrary units). Resting variables in each posture were compared using a paired t-test. All data were analyzed using a two-within repeated-measures ANOVA (posture x mental stress time). Baseline and recovery data were averaged for statistical comparison and compared using a two-within repeated measure ANOVA (posture x time). Perceived stress levels were compared using a Wilcoxon ranked sign test. Significance was considered at a p value of < 0.05. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.

Results

Renal vascular responses to mental stress

Baseline

Baseline measurements are presented in Table 1. Heart rate was significantly higher in the upright compared to the supine posture. There was no difference in ankle pressures between the upright and supine postures. Renal vascular conductance was lower in the upright than in the supine posture.

Table 1.

Baseline measurements in the supine and upright postures and perceived stress levels during mental stress.

| Variable | Renal | Superior Mesenteric | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supine (n = 8) | Upright (n = 8) | Supine (n = 9) | Upright (n = 9) | |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 88 ± 3 | 83 ± 6 | 91 ± 11 | 87 ± 6 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 57 ± 2 | 79 ± 4* | 59 ± 2 | 84 ± 5* |

| Forearm blood flow (ml/100 ml/min) | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.2* | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.2* |

| Forearm vascular conductance (units) | 0.038 ± .004 | 0.017 ± .002* | 0.034 ± .007 | 0.016 ± .003* |

| Visceral flow velocity (cm/sec) | 62 ± 4 | 55 ± 5 | 64 ± 9 | 48 ± 6* |

| Visceral artery conductance (units) | 0.75 ± .09 | 0.57 ± .08* | 0.77 ± .14 | 0.49 ± .08* |

| Perceived Stress during mental stress | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

Values are mean ± S.E.

Significantly different from respective supine posture (p < 0.05).

Responses to mental stress

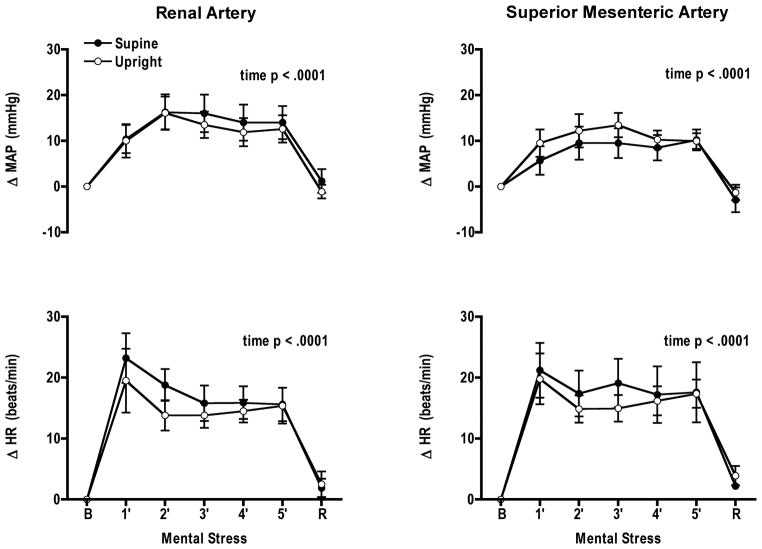

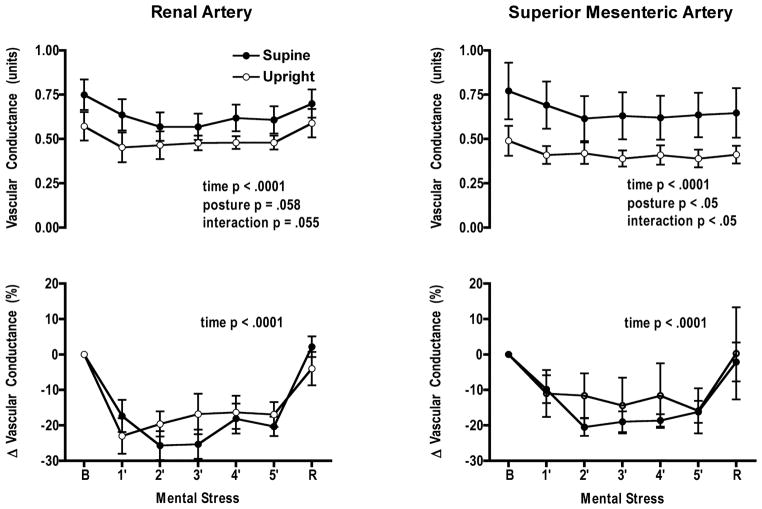

Mental stress significantly increased heart rate and mean arterial pressure from baseline in both postures; however, no interaction was observed between postures (Fig. 1). RBFV decreased significantly with time in both postures (p < 0.0001). Renal vascular conductance decreased with time in both postures and the posture × mental stress time interaction was significant (p = 0.05) (Fig. 2). When changes in RBFV and renal vascular conductance were expressed as percent change from baseline there was only a significant mental stress time effect. Perceived stress levels in each posture were not different (supine 3 ± 0.2; upright 3 ± 0.2) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Comparable increases in mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) during mental stress in the supine and upright postures while measuring blood flow velocity in either the renal or superior mesenteric artery. B, baseline, R, recovery.

Figure 2.

Vascular conductance decreased from baseline during mental stress in the renal and superior mesenteric arteries in both postures. A significant interaction was recorded when absolute values were compared for both postures in both arteries. However, when changes in conductance were expressed as a percent change from baseline, vascular responses to mental stress did not differ between postures. B, baseline, R, recovery.

Responses during recovery

Mean arterial pressure and heart rate were not different from their respective baseline in either posture. RBFV and renal vascular conductance returned to baseline in both postures.

Superior mesenteric vascular responses to mental stress

Baseline

Baseline measurements are presented in Table 1. Heart rate was significantly higher in the upright compared to supine posture. There was no difference in ankle pressures between the upright and supine postures. SMBFV and superior mesenteric vascular conductance were lower in the upright posture.

Responses to mental stress

Mean arterial pressure and heart rate increased during mental stress but the increase was not significantly different between postures (Fig. 1). SMBFV and superior mesenteric artery conductance decreased during mental stress in both postures (p = 0.02 and p = 0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 2). The decrease in SMBFV was not significantly different in each posture but the decrease in superior mesenteric artery conductance was (posture × mental stress time p = 0.013). When changes in SMBFV and superior mesenteric artery conductance were expressed as a percent change from baseline there was no significant interaction. Perceived stress levels in each posture were not different (supine 3 ± 0.2; upright 3 ± 0.2) (Table 1).

Responses during recovery

Mean arterial pressure and heart rate were not significantly different from baseline for both postures. SMBFV and superior mesenteric conductance did not change from baseline in both postures.

Forearm vascular responses to mental stress

Baseline

Baseline measurements are presented in Table 1. FBF and forearm vascular conductance were significantly less in the upright compared to the supine posture for both the renal and superior mesenteric artery trials.

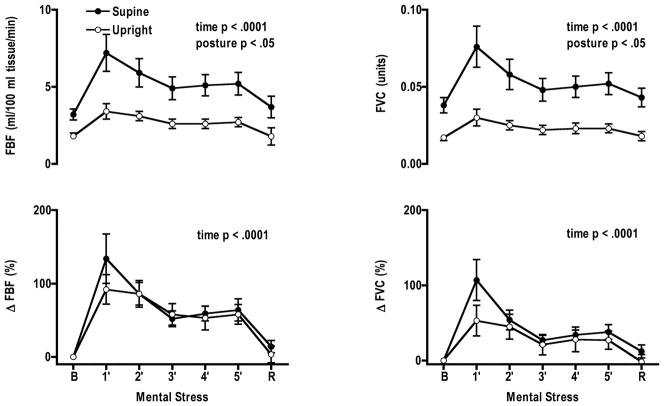

Responses to mental stress

During the renal trials FBF and forearm vascular conductance increased significantly from baseline during mental stress in each posture (Fig. 3). FBF and forearm vascular conductance increased more in the supine posture compared to the upright posture. However, when changes in FBF and forearm vascular conductance were expressed as percent change from baseline, increases in FBF and forearm vascular conductance did not differ. The response patterns during the superior mesenteric artery trials were the same as the renal.

Figure 3.

Forearm blood flow (FBF) and vascular conductance (FVC) increased from baseline during mental stress in both postures in the renal trials. Greater increases in FBF and FVC were observed in the supine compared to the upright postures. Percent change from baseline in FBF and FVC were not significantly different during mental stress in the supine and upright postures. B, baseline, R, recovery.

Responses during recovery

During the renal trial FBF was elevated in the supine posture (posture × time, p = 0.02), while in the upright posture it returned to baseline. When differences in FBF were expressed as a percent change from baseline there was no significant posture by mental stress time interaction. Forearm vascular conductance was greater during recovery in the supine (12.1 ± 9.6) compared to upright posture (1.8 ± 10.2; p = 0.013). FBF and vascular conductance did not differ from baseline in the superior mesenteric trials.

Leg vascular responses during mental stress in the upright and supine postures

Baseline

Mean arterial pressure and heart rate were significantly higher during the upright posture (Table 2). LBF and leg vascular conductance were significantly less in the upright posture.

Table 2.

Baseline measurements in the supine and upright postures and perceived stress levels during mental stress.

| Variable | Leg Blood Flow | Sympathetic Nerve Activity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supine (n = 9) | Upright (n = 9) | Supine (n = 5) | Upright (n = 5) | |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 80 ± 2 | 88 ± 2* | 80 ± 4 | 95 ± 6* |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 57± 2 | 80 ± 3* | 58± 2 | 80 ± 5* |

| MSNA: burst frequency (bursts/min) | 7 ± 3 | 19 ± 4* | ||

| MSNA: total activity (arbitrary units) | 525 ± 200 | 1807 ± 412* | ||

| Leg blood flow (ml/min) | 254 ± 41 | 132 ± 24* | ||

| Leg vascular conductance (units) | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.3* | ||

| Perceived stress during mental stress | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

Values are mean ± S.E.

Significantly different from respective supine posture (P < 0.05). Total activity is equal to sum of bursts area. MSNA, muscle sympathetic nerve activity.

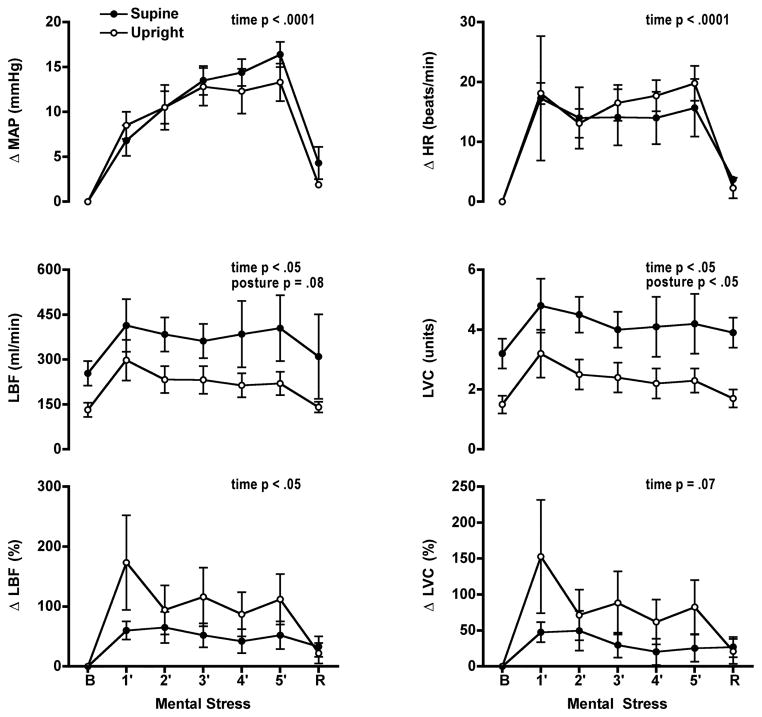

Responses to mental stress

Mental stress elicited comparable increases in mean arterial pressure and heart rate in both postures (Fig. 4). LBF and leg vascular conductance increased during mental stress in both postures. The increase in LBF did not differ between the postures but the increase in vascular conductance was larger in the supine posture. When changes in LBF and vascular conductance were expressed as a percent change from baseline the pattern of the leg vascular responses did not differ between the two postures. Perceived stress levels in each posture were not different (supine 3 ± 0.3; upright 3 ± 0.4) (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Mental stress increased mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) in both postures (n = 9). Leg blood flow (LBF) and vascular conductance (LVC) increased from baseline during mental stress in both postures. Greater increases in LVC were observed in the supine compared to the upright postures. Percent change from baseline in LBF and LVC were not significantly different during mental stress in the supine and upright postures. B, baseline, R, recovery.

Responses during recovery

Mean arterial pressure was not significantly different from baseline for both postures. Heart rate was significantly higher in the upright posture following mental stress but not in the supine posture (upright 87 ± 4 beats/min, supine 60 ± 2 beats/min). LBF and leg vascular conductance did not change from baseline in both postures.

Muscle sympathetic nerve activity during mental stress in the upright and supine postures

Baseline

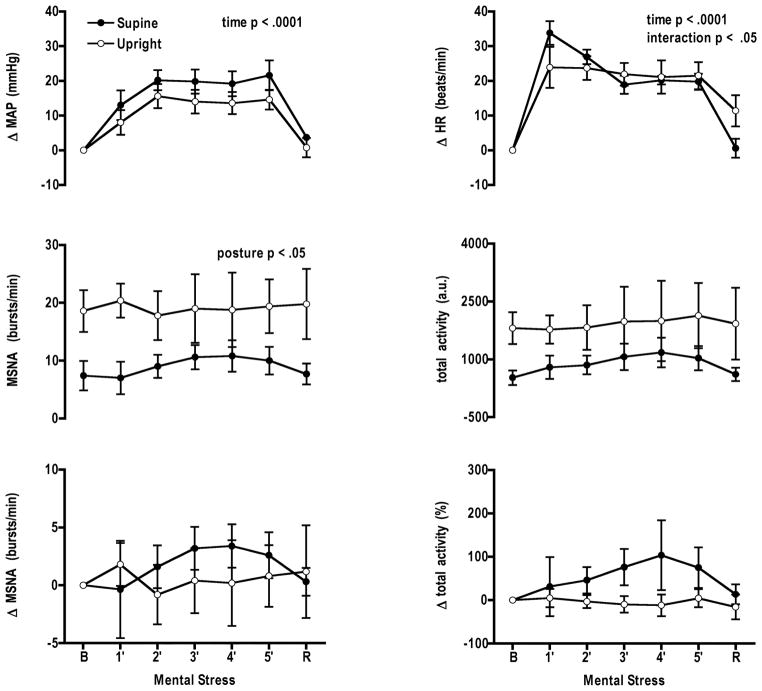

At baseline mean arterial pressure, heart rate, burst frequency, and total activity were significantly higher during the upright posture (Table 2). Mean arterial pressure and heart rate increased during mental stress in both postures (Fig. 5). There was no significant change in burst activity or percent change in total activity during mental stress. Perceived stress levels in each posture were not different (supine 3 ± 0.2; upright 3 ± 0.2) (Table 2).

Figure 5.

During muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) trials mental stress increased mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) in both postures (n = 5). Changes in MSNA burst frequency and total activity did not differ between the two postures. B, baseline, R, recovery.

Discussion

Assumption of the upright posture is characterized by increases in heart rate, sympathetic activity, and total peripheral resistance. Because sympathetic activity is augmented in the upright posture we hypothesized that neurovascular responses to mental stress would be diminished in the upright posture, but the pattern of neurovascular responses would be the same. In the current study the pattern of neurovascular responses to mental stress was the same in both the upright and supine postures although absolute measurements differed significantly between postures. This conclusion is supported by these findings. First, during mental stress changes in mean arterial pressure, heart rate, and MSNA did not differ between postures. Second, decreases in relative renal and superior mesenteric artery blood flow and increases in relative FBF and LBF were similar in both postures during mental stress. Therefore, the upright posture blunts limb vascular responses to mental stress and augments visceral vasoconstriction.

Previous studies investigating the pattern of cardiovascular responses to mental stress have demonstrated that mental stress can override baroreflex control of heart rate, blood pressure and MSNA in the supine posture or during baroreceptor loading induced by phenylephrine infusion (Anderson et al., 1987; Anderson et al., 1991). We found that during mental stress and head-up tilt, heart rate and blood pressure increased; suggesting mental stress is able to override baroreflex control of heart rate and blood pressure even in the upright posture. Therefore, mental stress is able to override baroreceptor control either during periods of baroreceptor unloading or loading.

It has been speculated that there is a link between mental stress induced forearm vasodilation and lower cerebral perfusion that may contribute to syncope (Roddie, 1977). In the current study we observed that increased blood flow in the periphery was mirrored by decreased blood flow to the visceral organs. The decrease in visceral blood flow may serve as a mechanism to fend off syncope onset caused by increases in blood flow to the limbs. The exact mechanisms responsible for the observed differences in blood flow responses during mental stress between the viscera and skeletal muscle remains unclear. We found MSNA increased in the upright posture, but MSNA responses were not altered during mental stress. This supports our previous finding that the pattern of vascular control during mental stress in the extremities is not associated with sympathetic outflow (Carter et al., 2005b). Blood flow control in the limbs may be controlled by other mechanisms, including nitric oxide and circulating epinephrine (Dietz et al., 1994; Lindqvist et al., 1996; Cardillo et al., 1997; Halliwill et al., 1997). Vascular control during mental stress in the viscera may be associated with sympathetic outflow, which directly contrasts with limb blood flow. In the renal artery, Tidgren & Hjemdahl (1989) reported that venous overflow of norepinephrine increased by 214% during mental stress and that the increase correlated with renal vasoconstriction. Infusion of epinephrine at rest into the same subjects did not change renal blood flow, which contrast with the forearms where beta-adrenergic blockade decreases mental stress induced vasodilation (Halliwill et al., 1997; Lindqvist et al., 1997). Chaudhuri et al. (1992) reported that during mental stress the percent change in superior mesenteric blood flow in control subjects was greater than patients suffering from autonomic failure, suggesting a possible vasoconstriction caused by the sympathetic nervous system. Control of visceral blood flow during mental stress may be similar to the heart, where release of norepinephrine has been found to increase during mental stress disproportionately to norepinephrine from the whole body (Esler et al., 1989; Esler et al., 1990). This suggests that visceral blood flow during mental stress may be controlled by sympathetic nerve activity. Therefore, measurement of peripheral MSNA during some stressors may not reflect visceral sympathetic control, even though resting MSNA has been found to correlate with renal norepinephrine spillover (Wallin et al., 1996).

Both mental stress and the upright posture individually are associated with onset of myocardial ischemia (Deanfield et al., 1984; Smith & Little, 1992; Krantz et al., 1996), alterations in endothelial function (Ghiadoni et al., 2000; Spieker et al., 2002; Guazzi et al., 2004; Guazzi et al., 2005), and blood pressure abnormalities (Robertson & Davis, 1995; Yan et al., 2003; Fessel & Robertson, 2006). The combined influence of mental stress and orthostatic challenge is poorly understood in relation to these pathological conditions. The results of the current study indicate that, even though the neurovascular response pattern to mental stress remains the same in the upright posture, the higher absolute heart rates, sympathetic activity, and peripheral resistance of the upright posture when combined with mental stress may exacerbate these pathological conditions.

The combined effect of mental stress and the upright posture on neurovascular function agrees with results of previous work in our lab examining the combined influence of mental stress and activation of the vestibulosympathetic reflex (Carter et al., 2002; Carter et al., 2005a). The current study and our previous work contrasts with Wasmund et al. (2002) who found that the combined influence of mental stress and another stressor, handgrip exercise, were not additive. Activation of the baroreflex and the vestibulosympathetic reflex require little if any input from central command whereas both mental stress and exercise do. Our findings and those of Wasmund et al. suggest that neurovascular responses to mental stress are additive with involuntary reflexes but may not be with physiological reflexes where central command controls part of the physiological response.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, we measured changes in renal and superior artery velocities as an index of blood flow. Because of the spatial resolution of our Doppler probe we are unable to measure diameters of these arteries accurately, therefore it is unapparent if renal and superior mesenteric artery diameter changed during upright tilt or mental stress. However, paradigms that increase renal vascular resistance (or decrease conductance) do not change the diameter of the conduit artery (Marraccini et al., 1996). Second, physiological responses to stress are highly variable and depend on individual responses and laboratory techniques (Roddie, 1977). Therefore, repeated trials of mental stress may alter neurovascular function differently. Within the current study we recorded similar stress levels, heart rate increases and mean arterial pressure increases in all six trials, for that reason we do not believe that variation in responses to mental stress influenced our results.

In summary, posture does not alter heart rate, blood pressure or MSNA responses to mental stress. Mental stress produces divergent vascular responses between the limbs and the viscera. Finally, the upright posture reduced conductance in all vascular beds examined, but the pattern of vascular responses during mental stress remains similar between the upright and supine postures.

References

- Anderson EA, Sinkey CA, Mark AL. Mental stress increases sympathetic nerve activity during sustained baroreceptor stimulation in humans. Hypertension. 1991;17:III43–49. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.4_suppl.iii43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EA, Wallin BG, Mark AL. Dissociation of sympathetic nerve activity in arm and leg muscle during mental stress. Hypertension. 1987;9:III114–119. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.9.6_pt_2.iii114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair DA, Glover WE, Greenfield AD, Roddie IC. Excitation of cholinergic vasodilator nerves to human skeletal muscles during emotional stress. J Physiol. 1959;148:633–647. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brod J, Fencl V, Hejl Z, Jirka J. Circulatory changes underlying blood pressure elevation during acute emotional stress (mental arithmetic) in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Clin Sci. 1959;18:269–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardillo C, Kilcoyne CM, Quyyumi AA, Cannon RO, 3rd, Panza JA. Role of nitric oxide in the vasodilator response to mental stress in normal subjects. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:1070–1074. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00605-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JR, Cooke WH, Ray CA. Forearm neurovascular responses during mental stress and vestibular activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005a;288:H904–907. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00569.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JR, Kupiers NT, Ray CA. Neurovascular responses to mental stress. J Physiol. 2005b;564:321–327. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JR, Ray CA, Cooke WH. Vestibulosympathetic reflex during mental stress. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1260–1264. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00331.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri KR, Thomaides T, Mathias CJ. Abnormality of superior mesenteric artery blood flow responses in human sympathetic failure. J Physiol. 1992;457:477–489. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deanfield JE, Shea M, Kensett M, Horlock P, Wilson RA, de Landsheere CM, Selwyn AP. Silent myocardial ischaemia due to mental stress. Lancet. 1984;2:1001–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz NM, Rivera JM, Eggener SE, Fix RT, Warner DO, Joyner MJ. Nitric oxide contributes to the rise in forearm blood flow during mental stress in humans. J Physiol. 1994;480 ( Pt 2):361–368. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler M, Jennings G, Lambert G. Measurement of overall and cardiac norepinephrine release into plasma during cognitive challenge. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1989;14:477–481. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler M, Jennings G, Lambert G, Meredith I, Horne M, Eisenhofer G. Overflow of catecholamine neurotransmitters to the circulation: source, fate, and functions. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:963–985. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessel J, Robertson D. Orthostatic hypertension: when pressor reflexes overcompensate. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:424–431. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiadoni L, Donald AE, Cropley M, Mullen MJ, Oakley G, Taylor M, O’Connor G, Betteridge J, Klein N, Steptoe A, Deanfield JE. Mental stress induces transient endothelial dysfunction in humans. Circulation. 2000;102:2473–2478. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.20.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guazzi M, Lenatti L, Tumminello G, Guazzi MD. Effects of orthostatic stress on forearm endothelial function in normal subjects and in patients with hypertension, diabetes, or both diseases. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:986–994. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guazzi M, Lenatti L, Tumminello G, Puppa S, Fiorentini C, Guazzi MD. The behaviour of the flow-mediated brachial artery vasodilatation during orthostatic stress in normal man. Acta Physiol Scand. 2004;182:353–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwill JR, Lawler LA, Eickhoff TJ, Dietz NM, Nauss LA, Joyner MJ. Forearm sympathetic withdrawal and vasodilatation during mental stress in humans. J Physiol. 1997;504 ( Pt 1):211–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.211bf.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer M, Boutcher YN, Boutcher SH. The role of cardiopulmonary baroreceptors during the forearm vasodilatation response to mental stress. Psychophysiology. 2003;40:249–253. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi N, Someya N, Endo MY, Miura A, Fukuba Y. Vasoconstriction and blood flow responses in visceral arteries to mental task in humans. Exp Physiol. 2006;91:215–220. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.031971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitano A, Shoemaker JK, Ichinose M, Wada H, Nishiyasu T. Comparison of cardiovascular responses between lower body negative pressure and head-up tilt. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:2081–2086. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00563.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz DS, Kop WJ, Gabbay FH, Rozanski A, Barnard M, Klein J, Pardo Y, Gottdiener JS. Circadian variation of ambulatory myocardial ischemia. Triggering by daily activities and evidence for an endogenous circadian component. Circulation. 1996;93:1364–1371. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.7.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist M, Kahan T, Melcher A, Bie P, Hjemdahl P. Forearm vasodilator mechanisms during mental stress: possible roles for epinephrine and ANP. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:E393–399. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.270.3.E393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist M, Melcher A, Hjemdahl P. Attenuation of forearm vasodilator responses to mental stress by regional beta-blockade, but not by atropine. Acta Physiol Scand. 1997;161:135–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1997.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraccini P, Fedele S, Marzilli M, Orsini E, Dukic G, Serasini L, L’Abbate A. Adenosine-induced renal vasoconstriction in man. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:949–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D, Davis TL. Recent advances in the treatment of orthostatic hypotension. Neurology. 1995;45:S26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roddie IC. Human responses to emotional stress. Ir J Med Sci. 1977;146:395–417. doi: 10.1007/BF03030998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell LB, Detry JM, Blackmon JR, Wyss C. Importance of the splanchnic vascular bed in human blood pressure regulation. J Appl Physiol. 1972;32:213–220. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.32.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch NJ, Shepherd JT, Webb RC, Vanhoutte PM. Different behavior of the resistance vessels of the human calf and forearm during contralateral isometric exercise, mental stress, and abnormal respiratory movements. Circ Res. 1981;48:I118–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Little WC. Potential precipitating factors of the onset of myocardial infarction. Am J Med Sci. 1992;303:141–144. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieker LE, Hurlimann D, Ruschitzka F, Corti R, Enseleit F, Shaw S, Hayoz D, Deanfield JE, Luscher TF, Noll G. Mental stress induces prolonged endothelial dysfunction via endothelin-A receptors. Circulation. 2002;105:2817–2820. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000021598.15895.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun BC, Emond JA, Camargo CA., Jr Direct medical costs of syncope-related hospitalizations in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:668–671. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidgren B, Hjemdahl P. Renal responses to mental stress and epinephrine in humans. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:F682–689. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.4.F682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin BG, Sundlof G. Sympathetic outflow to muscles during vasovagal syncope. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1982;6:287–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(82)90001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin BG, Thompson JM, Jennings GL, Esler MD. Renal noradrenaline spillover correlates with muscle sympathetic activity in humans. J Physiol. 1996;491 ( Pt 3):881–887. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasmund WL, Westerholm EC, Watenpaugh DE, Wasmund SL, Smith ML. Interactive effects of mental and physical stress on cardiovascular control. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:1828–1834. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00019.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan LL, Liu K, Matthews KA, Daviglus ML, Ferguson TF, Kiefe CI. Psychosocial factors and risk of hypertension: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. JAMA. 2003;290:2138–2148. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]