Abstract

In this paper, we model the associations of childhood health on adult health and socio-economic status outcomes in China using a new sample of middle aged and older Chinese respondents. Modeled after the American Health and Retirement Survey (HRS), the CHARLS Pilot survey respondents are 45 years and older in two quite distinct provinces—Zhejiang, a high growth industrialized province on the East Coast and Gansu, a largely agricultural and poor province in the West. Childhood health in CHARLS relies on two measures that proxy for different dimensions of health during the childhood years. The first is a retrospective self-evaluation using a standard five-point scale (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor) of general state of one's health when one was less than 16 years old. The second is adult height believed to be a good measure of levels of nutrition during early childhood and the prenatal period. We relate both these childhood health measures to adult health and SES outcomes during the adult years. We find strong associations of childhood health on adult health outcomes particularly among Chinese women and strong associations with adult BMI particularly for Chinese men.

This research examines the association of health of Chinese children on their subsequent health and economic status as adults. To do so, we use recently collected data from the Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey (CHARLS) that was fielded in 2008. The influence of early life and childhood conditions and health on adult outcomes has been examined in many Western countries (Banks, Oldfield, and Smith 2011) and in this paper we extend that investigation to the Chinese context. The health and economic environment in which CHARLS respondents were raised is far different than that the contemporary China in which they now live. CHARLS respondents were born during years 1963 and earlier. During that time, the history of China was quite challenging and tumultuous, especially for children. The enormous diversity in the circumstances of the villages and families in which CHARLS respondents were raised may have lingering and significant impacts on their economic and health lives during adulthood.

The revival of interest in determinants and consequences of poor childhood health in general can be traced partly to the impact of studies by David J. Barker (1997). In his work, he provides evidence that even nutrition in utero impacts health outcomes much later during one's adulthood. While controversial, data from natural experiments lend some support to this view. For example, Ravelli et al. (1998) studied people born in Amsterdam who were exposed prenatally to famine conditions in 1944-1945. When compared to those conceived a year before or after the famine, prenatal exposure to famine, especially during late gestation, was linked to decreased glucose tolerance in adults producing higher risks of diabetes. Hoddinott et al. (2008) and Maluccio et al. (2009) draw on a protein supplementation experiment conducted in Guatemala during the 1970s in which children in randomly chosen villages were offered protein supplements during their pre-school ages and show that completed schooling was significantly higher for the supplemented group, as were labor market earnings when they became adults.

In the last few years, economists have done some insightful work on this topic. As one example among many, Case, Fertig, and Paxson (2005) investigated persistent associations between childhood health on adult health, employment, and some measures of SES using a 1958 British birth cohort who were followed prospectively into their adult years. They find that people who experienced poorer health outcomes either in terms of low birth weight or the presence of chronic conditions when they were children not only had worse health as adults, but they passed fewer O-level exams, worked less during their adult years, and had lower occupational status at age 42 even after some standard key measures of parental background such as education and income were controlled.

Using the American Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) which is an all age income panel survey that has been ongoing since 1968, in a recent study Smith (2009b) examined the association of childhood health on adult SES outcomes, including levels and trajectories of education, family income, household wealth, individual earnings and labor supply. Smith's analysis was conducted with a panel who were originally children and are now well into adulthood. With the exception of education, Smith reports that poor childhood health has a strong association on all outcomes with estimated associations larger when unobserved family effects are controlled. An individual's general health status during childhood appears to have significant direct and indirect associations on several salient adult SES financial outcomes, including one's ability to earn in the labor market, total family income, and wealth. In a companion study, Smith and Smith (2010) demonstrate that a substantial component of this association was due to psychological disorders during childhood. These findings were replicated in the British context using prospective data from the 1958 British cohort panel (Goodman, Joyce, and Smith 2011). Whether these types of results carry over to the Chinese context in population studies is not yet known.

Our goal is not to estimate causal models since that goes beyond the current ability of our data to isolate such effects. However, our empirically estimated partial associations between childhood health and adult outcomes can be viewed as an important first step in such an inquiry. As the panel aspects of the full CHARLS sample which will have many more observations comes available in a few years, the ability to use this data to isolate exogenous events in communities that would plausibly alter childhood health in China will be much improved.

This paper is divided into five sections. The next section describes the CHARLS data and variables that will be used in our analysis. Section 3 outlines the types of statistical models that will be estimated in order to model the association between childhood health and the adult health and SES outcomes in the Chinese context. Our main empirical findings are contained in section 4 and the final section highlights our main conclusions.

2.1 Data—CHARLS Pilot Survey

The 2008 wave of China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS Pilot) was conducted in Zhejiang and Gansu provinces in China by the China Center for Economic Research of Peking University (see Zhao et al. 2009).1 Zhejiang, located in the developed coastal region, is one of the most dynamic provinces in terms of its fast economic growth, private sector, small-scale industrialization, and export orientation, while Gansu, located in the less developed western region, is one of the poorest, most rural provinces in China. In 2008, Zhejiang had the highest rural and urban incomes per capita after Shanghai and Beijing, and Gansu had the second lowest rural per capita income and fourth lowest urban per capita income.

The sampling design of the 2008 wave of CHARLS was aimed to be representative of residents 45 and older in the two provinces. The sampling protocol is that one member of the household age 45 and over is sampled and their spouse (no matter what the spouse's age is). In our analysis below, the respondent and his/her spouse are both included in our analysis as long as they are at least 45 years old.

Within each province, CHARLS randomly selected 13 county level units (rural counties or urban districts) by PPS (Probability Proportional to Size), stratified by regions and urban/rural. The goal was to achieve a sample size of 16 households in each village level unit using a complete list of dwelling units generated from a map for each province.2 CHARLS did not allow for sample replacement for fear of causing interviewers to non-randomly select households to interview. Instead, a pre-determined number of households were interviewed in every village. In rural villages, the number was 25 and in urban communities it was 36 to reflect the differences in age eligibility and response rates between urban and rural areas. Because the resulted sample size is likely to be different from 16, sampling weights were created for unequal representation of each sample household. In our estimated behavioral equations in the paper, sampling weights are not relevant in any case. Based on this sampling procedure and accounting for age ineligibility and non-response, there were 5-24 households in each community; and one or two individuals in each household who were interviewed depending on marital status in the household. The total sample size was 2,685 individuals in 1,570 households.

The CHARLS Pilot experience was very positive. As indicated by the data in Table 1, the overall response rate was 85%, 79% in urban areas and 90% in rural areas.3 The response rate was about the same in the two provinces 83.9% in Zhejiang and 85.8% in Gansu. These high response rates reflected the detailed procedures that were put in place to insure a high response to the survey.

Table 1.

Sample Size and Response Rate %

| Total | Urban | Rural | Zhejiang | Gansu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sampled | 2592 | 1281 | 1311 | 1350 | 1242 |

| Age-eligible rate | 69.3 | 65.1 | 73.4 | 71.3 | 67.2 |

| Response rate* | 84.8 | 79.3 | 89.7 | 83.9 | 85.8 |

| Total Households responded | 1570 | 691 | 879 | 831 | 739 |

Response rate is based on the age-eligible households.

See Zhao et al. (2009).

2.1 Measurement in CHARLS—Adult Health

The CHARLS main household questionnaire of the 2008 survey consists of six modules, covering demographics, family, health status, health care, employment, and household economy (income, consumption and wealth). All data are collected by face-to-face, computer-aided personal interviews (CAPI). Both questionnaire and field procedures were repeatedly tested to ensure high data quality. CHARLS is a member of the set of harmonized international aging surveys that were modeled after the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) in the United States. In addition to the typical HRS survey content, a detailed community-level questionnaire was formulated. This community questionnaire focuses on important infrastructure available in the community, plus on the availability of health facilities used by the elderly and on prices of goods and services often used by the elderly.

The main adult outcome variables we will examine in this paper include key adult health outcomes, health behaviors, and SES outcomes. Adult health and health behavior variables come from the health module. They are current self-reported general health status, doctor diagnoses of chronic illnesses, depression, word recall, lifestyle and health behaviors (physical activities, smoking, drinking), subjective expectation of mortality, activities of daily living (ADLs), and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). IADLs include several activities, such as household chores like cooking and shopping that are the primary responsibility of women so that men may have more difficulty with these activities in general and especially when they are not healthy. It is worth noting that some health variables, such as weight and height, are obtained from health measurements conducted in the field.

2.2 Measures of Childhood Health

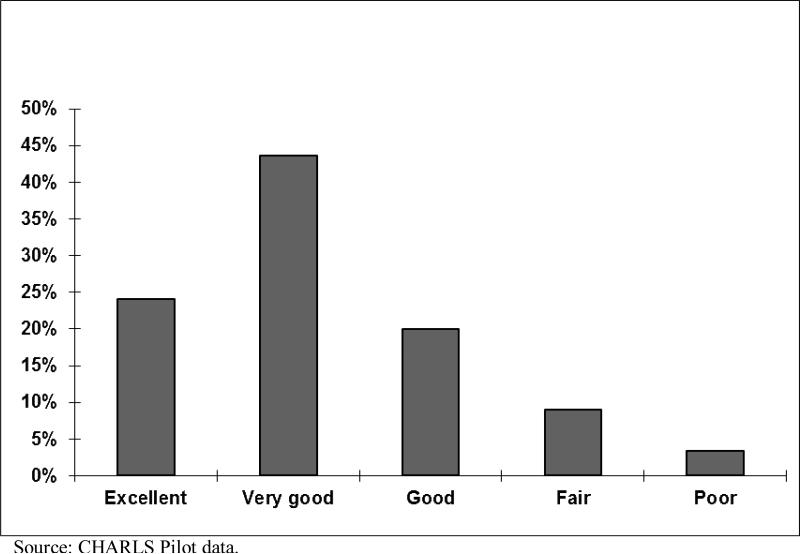

We index childhood health in this study using two complementary concepts: (1) respondent retrospective summaries of their health during their childhood years, and (2) their adult height. For the first measure, each respondent is asked the following question: “How would you evaluate your health during childhood, up to and including age 15?” The choices offered are excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor. Following the prior practice in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID and the HRS surveys, this childhood health question in CHARLS represents a retrospective self-evaluation on a five-point scale (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor) of the general state of one's health when one was less than 16 years old.

Smith validated this variable in the context of the US as providing a good summary measure of overall childhood health. In the United States, Smith (2009a) demonstrated that this childhood index was related to the presence of many childhood physical diseases during childhood including respiratory diseases, heart disease, childhood diabetes, headaches and migraines, ear infections, and stomach problems. One component of overall health during childhood that is clearly captured well by this retrospective subjective measure is psychological problems that occurred during the childhood and adolescence years (Smith and Smith 2010). In addition, Smith (2009a) also showed that changes in adult health did not systematically alter the self-reported childhood health, suggesting that the potential problem of backward attribution from adult health to childhood health was not a serious problem in the PSID. It is important to note that since panel data are not yet available with repeated questions on childhood health as adult health changes in the panel, there have to date been no such validation tests in the Chinese context. More work on these validation issues would be very useful in the future.

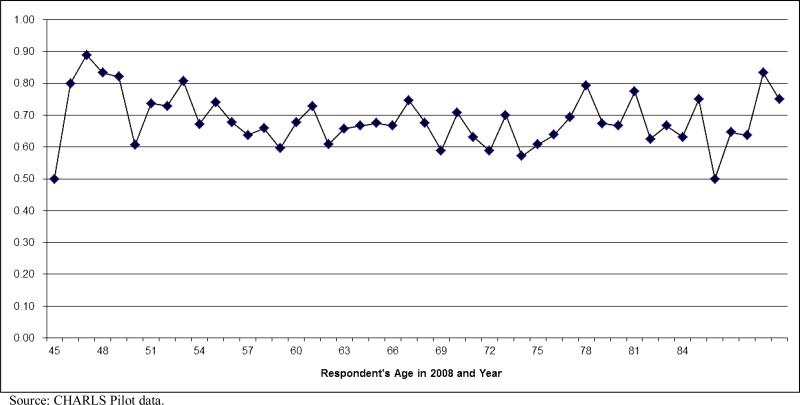

Figure 1 shows the distribution of responses to the subjective childhood health question given to CHARLS respondents. Approximately, two in three CHARLS respondents said that their childhood health was either excellent or very good, while one in three gave good, fair, or poor as a response. Figure 2 plots the fraction of CHARLS respondents who gave a response of either excellent or very good childhood health simultaneously by single year of age and by year of birth. While average responses by single year of age or year are noisy due to relatively small sample sizes, the overall pattern of response by age is relatively flat.

Figure 1.

Self-Reported Childhood Health of CHARLS Respondents

Figure 2.

Percentage Reporting Excellent/Very Good Childhood Health

However, this does not imply that overall childhood health in these two provinces of China remained unchanged over time in spite of the rapid economic development that took place there. First, mortality selection which becomes more and more pronounced at older ages is systematically selecting out those who are less healthy and presumably had less healthy childhoods. Correcting for mortality selection would no doubt impart a negative slope with age (equivalently birth cohort) to Figure 2. Second, as mentioned above, the subjective childhood health summary includes both dimensions of physical illnesses and psychological illness during childhood (Smith and Smith 2010). While it is reasonable that childhood physical illnesses decline with development, especially those physical illnesses related to nutrition and sanitation in early childhood diseases, that is far less clear with mental illness as children may find the demands of development and the changes associated with it stressful in their lives.

Finally, Figure 3 plots the relationship between childhood health and adult health. For each respondent's age, we plot whether adult health was either excellent or very good for two groups—those whose childhood health was good or more and those whose childhood health was fair or poor. The odds of being in good health as an adult are four times higher if the respondent was in good health as a child.

Figure 3.

Adult Health by Child Health in CHARLS Pilot

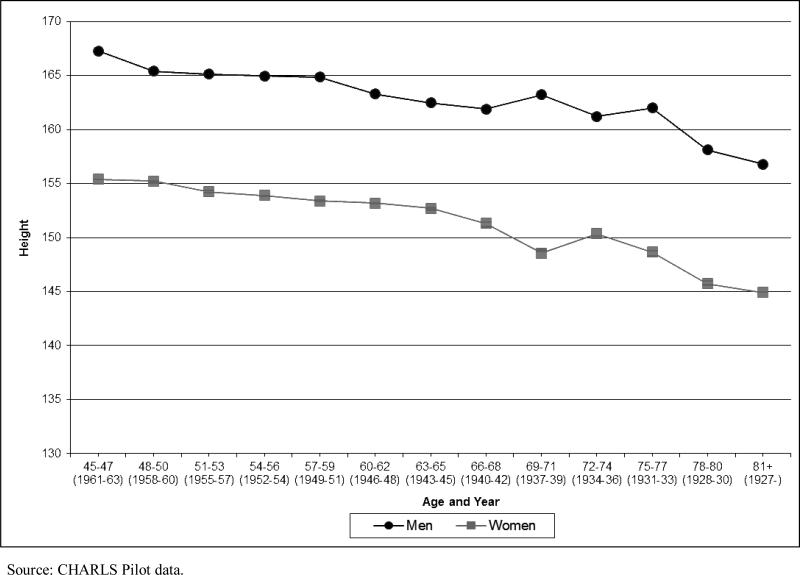

Adult height has an even longer tradition as a measure of childhood health especially in developing countries. Adult height has been used by economists, historians and nutritionists as a measure of population health (see Fogel 2004 and Steckel 1995, 2008 for surveys of the history literature). Mean adult height, particularly in the twentieth century rose in many countries, including developing countries, as economic development proceeded (see Strauss and Thomas 1995 and Steckel 1995 for evidence). Adult height is determined both by childhood height and the adolescent growth spurt. Childhood height is often thought to be largely determined in pre-school ages, particularly before age 3 (Martorell and Habicht 1986; Habicht, Martorell, and Rivera 1995). Childhood height reflects health generally, not only nutritional intakes and expenditures, but some illnesses, particularly from infectious diseases (Martorell and Habicht, 1986), and appears to be related to adult cognitive ability (Case and Paxson 2008). Consequently, adult height will, in part, reflect these differences in childhood height, and some components of childhood health differences more generally.

Many studies have examined socio-economic determinants of early childhood heights (see Behrman and Deolalikar 1988; and Strauss and Thomas, 1995 for reviews). Well known studies by Habicht et al. (1974) and Martorell and Habicht (1986) have measured the childhood heights of well-nourished children from many ethnic groups around the world and found that ethnic differences in pre-school child heights are very small in comparison to SES differences. Hence adult heights will reflect in part differences during childhood in SES.

Figure 4 plots the relationship between adult height and age and year of birth (three year age averages) separately for men and women. While there exists some shrinkage, especially at older ages, which is an age effect, most of the age pattern in these graphs can be read as indicating cohort effects of improved nutrition associated with development leading to taller adults for both men and women. These patterns are not trivial. For men in the 30 years between ages 45 and 75, younger Chinese men born 30 years earlier are on average five centimeters taller. This represents an average increase in adult heights of over 1cm per decade, which is faster than other growth in adult heights in other developing countries over this period (see Strauss and Thomas 1995). The comparable number for women is an additional six centimeters in height over time. This sharp pattern of height by age is another indication that average height increases in periods of economic development reflecting the better nutrition in early childhood.

Figure 4.

Adult Height by Age

2.3 Location and Communities

Respondents in CHARLS are at least 45 years old, and hence their childhood lives reflect events in China that in part occurred many decades ago. In particular, many of these respondents entered and worked in the labor market before the period of China's rapid economic growth, which among other things generated considerable migration of younger workers particularly to the more economically dynamic provinces. These migratory streams raise the issue of the connection between the current locations of CHARLS respondents to their actual places of residence during their childhood.

Table 2 presents data on the relationship between current location and place at residence at birth for men and women separately. In the CHARLS Pilot, respondents were located in two provinces—Gansu and Zhejiang and in 30 counties and 95 communities and villages in those provinces. The mobility portrait that comes from Table 2 is clear. CHARLS male respondents who are by design ages 45 and over were relatively immobile. At the time of the CHARLS interview, 75% of CHARLS male respondents lived in the same community or village in which they were born. Even among those who did migrate after birth, they did not venture far as less than ten percent of CHARLS male respondents moved from the village in which they were born. While CHARLS female respondents were more mobile, that mobility was associated with a move to or with their spouse to another village in the same county where they were born. About ninety percent of CHARLS female respondents did not move beyond the county of their birth.

Table 2.

Location of Birth of CHARLS Respondents

| Where were you born? | Men | Women | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Same place | 75.1% | 25.1% | 50.4% |

| Another village in county | 15.1% | 61.8% | 38.2% |

| Another county in province | 5.8% | 9.1% | 7.4% |

| Another province | 4.0% | 4.1% | 4.0% |

We re-estimated the analysis presented in this paper in section 4 below after deleting the observations who were meaningful migrants in terms of distance—that is the sample of observations who moved across county or province boundaries since the year of their birth. These results were very similar to those reported in this paper which includes these migrants in large part since sample sizes are only reduced by around 10%.

One important role that communities in China can play is that that they vary considerably in their historical and current experiences of local shocks such as famines, infectious diseases, earthquakes, and economic conditions. In CHARLS, these experiences, which may be helpful in establishing causal effects, are being recorded in community diaries. We do not use this information here since the sample sizes in the CHARLS pilot are not sufficient by year of birth or place of residence to estimate them, an issue that will be resolve in the full CHARLS study.

2.4 Measurement in CHARLS—Economic Resources

Unlike most existing HRS type surveys most of which did not measure consumption in detail, financial dimensions of SES are measured in income, wealth, and detailed consumption expenditures. CHARLS also separately measures income and assets at the individual level as well as at the household level. CHARLS income components include wage income, self-employment income, agricultural income,4 pension income, and transfer income, where wage income is collected for each of the household members, and transfer income separates government transfers specific to individuals from those to households. Asset measurements collected at household level include housing, fixed assets, durables and land. Information on ownership status, value and characteristics of current residence as well as other housing owned by the household are recorded. Deposits and other investments are measured at the individual level, but debts are asked both for respondent and spouse, and for the household.

Household expenditures are collected in CHARLS since the literature has shown that expenditure can be a better welfare measures than income in developing countries (Strauss and Thomas 2008). Consumption items are collected at weekly, monthly and yearly frequencies respectively to minimize recall bias. Food expenditure is collected on weekly basis. It includes expenditures on dining out, food bought from market, and values of home-produced food consumed. Food expenditures induced by inviting guests for important events are collected to better reflect household food expenditure per capita in a normal week. Monthly-based expenditures are those usually spent each month, including fees for utilities, nannies, communications, etc. Yearly-based items record expenditures occurred occasionally in a year, including traveling, expenditures on durables, and education and training fees.

Table 3 displays mean and median values of income, expenditure, and net assets as revealed by CHARLS respondents. All values are in Yuan and income and expenditures are measured on a yearly periodicity. We distinguish between the urban and rural areas of the two sampled provinces. Examining first the more conventional measure of economic status, there are enormous differences in income across and within these geographic units. For example, mean income in urban Zhejiang is almost ten times that of rural Gansu. In both these geographic places, mean incomes are about twice that of median income indicating that there exists substantial income inequality within all regional sub-units as well. If anything, these disparities are even larger when wealth is used as the economic yardstick. Now mean wealth in urban Zhejiang is 45 times that in rural Gansu and wealth inequality is substantial in all sub-regions as indicated by the mean-median differences in each place.

Table 3.

Per Capita Household Total Income, Expenditure, and Net Wealth Across Regions

| Income | Expenditure | Net Wealth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Mean | Median | Mean | Median | |

| Urban Zhejiang | 22336 | 12200 | 10677 | 8258 | 218605 | 80600 |

| Rural Zhejiang | 10391 | 6513 | 7575 | 5810 | 63996 | 29908 |

| Urban Gansu | 8557 | 5367 | 7549 | 4641 | 51043 | 38900 |

| Rural Gansu | 2335 | 950 | 3843 | 2928 | 7858 | 3783 |

All values in Yuan. Income and Expenditures are per year.

Significant differences in amounts of economic resources exist when per capita expenditures are used as the economic metric, but these disparities are far smaller than those obtained with either income or consumption, which is to be expected because of both greater measurement error in income and wealth and because households tend to smooth their consumption. While differences between urban Zhejiang and rural Gansu in income were ten fold and in wealth were 45 fold, mean consumption in urban Zhejiang was 2.8 times that of rural Gansu. Especially when comparing urban and rural areas when most of the economic activity in rural activities is not monetized, income and wealth exaggerate the magnitude of the economic disparities. Respondents in traditional rural places working in a family business or farm often receive no monetary payment at all but do share in family consumption.

3.1 Statistical Models

In this paper, we model the association of our two measures of childhood health—the self-evaluation scale and adult height—on a set of adult health outcomes, health behaviors, and SES. Throughout this paper, we use ordinary least squares for continuous dependent variables and linear probability model (LP) for binary dependent variables. LP model estimates are consistent for estimating average partial associations of the regressors, which is our main interest. Robust standard errors of the regression coefficients are computed that also allow for clustering at the community level. By using robust standard errors for the linear probability regressions, we ensure that these standard error estimates are consistent (Wooldridge 2002).

Since location dummies are very important to our story, we discuss them next in more detail. In our statistical specification presented in the next section, we will explore several alternative measures of location of respondents. One specification contains dummy variables for province and urban-rural residence defined at the village/community level within province.5 Clearly this is a coarse definition of location.

An alternative and much finer definition controls for the PSU, or community in which people live by including community fixed effects. We have one dummy variable for each PSU, minus one of course.6 As noted in the discussion of the sampling above, our PSUs are either administrative villages or urban neighborhoods. These are small areas that are likely to be more homogeneous than cities or counties, or certainly than province. The idea here is that each community has factors that will affect health outcomes that are not captured by the provincial dummies interacted with rural or urban residence. These factors will include but are no means limited to health care prices, inherent healthiness of the area, common environmental forces especially those that impact health, public health infrastructure, local area economic resources, and other factors. F-tests for all combinations of dummy variables are reported as well.

In all models, we included both child health measures but they are typically only weakly correlated so that estimated effects are not sensitive to their simultaneous inclusion. We also provide joint tests of the joint significance of our childhood health measures. In addition, all models presented in this paper include a set of 10-year age dummies that in principle control for age and cohort related variation in the outcome of interest. To test for robustness, we re-estimated our models using five year and single year age dummies and the main results were very similar. Our second specification adds controls for province and rural-urban residence, while our third specification alternatively includes a set of dummy variables for community of residence. All models are estimated separately for men and women, and where the data indicate that important differences exist, we will present separate models for Gansu and Zhejiang province. Appendix Table 1 presents summary statistics for the variables we use in our analysis.

4.1 Empirical Estimates- Adult Health

Table 4 examines the estimated relationship between our two measures of childhood health—the five point subjective childhood health scale and adult height at the time of the interview—with several alternative dimensions of poor health in adulthood. More specifically, these adult poor health measures include poor adult health (adult health = poor on the subjective five point scale), being hypertensive (derived from a self-report that you were told by a medical person that you were hypertensive or having a hypertensive reading above 140/90), being undiagnosed conditional on being hypertensive (above the hypertensive reading and not having been medically diagnosed), the number of Activities of Daily Living7 (ADLs), the number of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living8 (IADLs) that people report “have difficulty” or “cannot do,” and respondent's subjective probability that they will not survive to age 75 (reported chance = “almost impossible” or “not very likely” as against “maybe,” “very likely,” and “almost certain”).9 This health outcome is limited to respondents who were less than 65 years old at the time of the CHARLS Pilot interview.

Table 4.

Estimates of Measures of Childhood Health on Health Outcomes (Robust standard errors in parenthesis below estimated coefficients)

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Poor Adult Health | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.045 (0.032) | -0.031 (0.031) | -0.033 (0.032) | -0.129*** (0.033) | -0.113*** (0.031) | -0.119*** (0.030) |

| height (cm) | -0.002 (0.003) | -0.002 (0.003) | -0.002 (0.003) | -0.004 (0.003) | -0.002 (0.003) | -0.001 (0.003) |

| F-test for both (p-value) | 1.27 (0.286) | 0.97 (0.383) | 0.82 (0.442) | 8.50*** (0.000) | 6.69*** (0.002) | 8.66*** (0.000) |

| N | 877 | 877 | 877 | 868 | 868 | 868 |

| Hypertensive | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.055* (0.030) | 0.056* (0.030) | 0.048 (0.032) | -0.006 (0.042) | -0.007 (0.042) | -0.015 (0.046) |

| height (cm) | -0.001 (0.002) | -0.001 (0.003) | -0.002 (0.003) | 0.006** (0.003) | 0.006* (0.003) | 0.002 (0.003) |

| F-test for both (p-value) | 1.65 (0.197) | 1.73 (0.183) | 1.17 (0.315) | 2.07 (0.132) | 1.80 (0.172) | 0.36 (0.698) |

| Undiagnosed hypertension | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.011 (0.054) | 0.022 (0.054) | 0.008 (0.058) | -0.055 (0.060) | -0.032 (0.057) | -0.055 (0.065) |

| height (cm) | -0.012*** (0.004) | -0.012*** (0.004) | -0.013*** (0.004) | -0.012** (0.004) | -0.011** (0.004) | -0.005 (0.005) |

| F-test for both (p-value) | 4.15** (0.019) | 4.27** (0.017) | 4.19** (0.018) | 5.40*** (0.006) | 4.25** (0.017) | 1.11 (0.334) |

| N | 335 | 335 | 335 | 425 | 425 | 425 |

| ADLs | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.001 (0.039) | 0.019 (0.037) | 0.013 (0.037) | -0.138** (0.056) | -0.123** (0.054) | -0.134** (0.059) |

| height (cm) | -0.004 (0.005) | -0.005 (0.005) | -0.005 (0.005) | -0.001 (0.004) | 0.000 (0.004) | -0.001 (0.004) |

| F-test for both (p-value) | 0.43 (0.653) | 0.55 (0.578) | 0.54 (0.585) | 3.01* (0.054) | 2.60* (0.080) | 2.56* (0.083) |

| IADLs | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.039 (0.069) | 0.011 (0.065) | 0.015 (0.061) | -0.147 (0.116) | -0.062 (0.097) | -0.066 (0.103) |

| height (cm) | -0.014** (0.006) | -0.016*** (0.006) | -0.015** (0.007) | -0.025*** (0.008) | -0.019*** (0.005) | -0.018*** (0.006) |

| F-test for both (p-value) | 2.69* (0.073) | 3.69** (0.029) | 2.76* (0.069) | 6.43*** (0.002) | 7.44*** (0.001) | 5.33*** (0.006) |

| Not very likely or almost impossible to survive to age 75a | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.073* (0.038) | -0.036 (0.036) | -0.032 (0.035) | -0.126*** (0.044) | -0.096** (0.037) | -0.083** (0.038) |

| height (cm) | -0.002 (0.003) | -0.004 (0.003) | -0.002 (0.003) | -0.001 (0.003) | 0.002 (0.003) | 0.001 (0.003) |

| F-test for both (p-value) | 2.13 (0.125) | 1.41 (0.250) | 0.64 (0.528) | 4.24** (0.017) | 3.48** (0.035) | 2.30 (0.106) |

| N | 583 | 583 | 583 | 596 | 596 | 596 |

Model (1) has controls for age group dummies only. Model (2) adds controls for urban-rural residence and province residence. Model (3) adds dummy variables for all communities.

For respondents less than age 65.

Is statistically significant at 1% level

is statistically significant at 5% level:

is statistically significant at 10% level. Sample sizes are only provided if they differ significantly from the numbers in the table.

One salient pattern in Table 4 is that our childhood health measures are more related to this set of adult health outcomes for women than for men. Among women, better childhood health using the subjective childhood health scale as the indicator reduces the prospects of being in poor health as an adult, lowers the number of ADLs a respondent has problems with as an adult, and decreases the probability that one would not survive to age 75. With the exception of lowering the odds of being undiagnosed and the number of IADLs with problems, the estimated associations are more likely to be statistically significant at conventional levels with the subjective scale measure than with the adult height measure. For both men and women, being taller statistically reduces the number of IADLs respondents have problems with and increases the likelihood of having a doctor diagnosis of hypertension.

Table 5 presents estimates for a subset of these adult health outcomes estimated separately for Gansu and Zhejiang. The statistical power of any analysis conducted by province is necessarily smaller, especially when we control for community fixed effects as we do here. Tests for statistically significant differences are presented in the final column under each gender. The general pattern of adult associations within province are similar to those contained in Table 4—a concentration of the relationship between childhood health and poor adult health within women compared to men. In addition, the results obtained in Table 5 suggest that this association for women is stronger in the lower income growth traditionally agricultural province of Gansu compared to the more high economic growth province of Zhejiang.

Table 5.

Estimates of Measures of Childhood Health on Health Outcomes (Robust standard errors in parenthesis below estimated coefficients)

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhejiang | Gansu | difference | Zhejiang | Gansu | difference | |

| Poor adult health | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.000 (0.037) | -0.070 (0.052) | -0.064 (0.062) | -0.133*** (0.039) | -0.098** (0.047) | 0.035 (0.060) |

| height (cm) | 0.001 (0.003) | -0.005 (0.004) | -0.006 (0.005) | -0.004 (0.003) | 0.003 (0.005) | 0.008 (0.006) |

| N | 468 | 409 | 481 | 387 | ||

| ADLs | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.012 (0.025) | 0.013 (0.071) | 0.008 (0.080) | -0.025 (0.040) | -0.285** (0.117) | -0.273** (0.122) |

| height (cm) | -0.006 (0.005) | -0.005 (0.009) | -0.003 (0.011) | 0.001 (0.003) | -0.002 (0.009) | -0.013 (0.010) |

| N | 466 | 405 | 480 | 383 | ||

| IADLs | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.018 (0.048) | 0.016 (0.123) | 0.036 (0.133) | 0.087 (0.070) | -0.323 (0.209) | -0.433* (0.222) |

| height (cm) | -0.014*** (0.005) | -0.020 (0.012) | -0.019 (0.014) | -0.008* (0.004) | - 0.034*** (0.011) | -0.049*** (0.015) |

| N | 448 | 362 | 452 | 336 | ||

| Not very likely or almost impossible to survive to age 75a | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.004 (0.031) | -0.064 (0.068) | -0.062 (0.073) | 0.017 (0.044) | -0.211*** (0.058) | -0.229*** (0.073) |

| height (cm) | -0.001 (0.003) | -0.005 (0.006) | -0.003 (0.007) | 0.002 (0.003) | -0.001 (0.006) | -0.004 (0.007) |

| N | 319 | 264 | 338 | 258 | ||

For respondents less than age 65.

Is statistically significant at one percent level

is statistically significant at five percent level:

is statistically significant at ten percent level. Community fixed effects are included.

4.2 Empirical Estimates—Adult BMI, Depression, and Memory

The next set of adult outcomes we explore relate to factors that are not directly measuring adult health outcomes, but that are closely related to adult health outcomes—BMI, memory, and depression. BMI is measured for each respondent by directly measuring their height and their weight. Direct measurement is preferable since it frees BMI of well-documented measurement error problems using self-reports. Using measured BMI, we model the probability of being undernourished (BMI < 18.5) and being overweight (BMI > 25). Memory is an average of the immediate word recall of ten words read to the respondent and a two-minute delayed recall of the same words. Depression is derived from a simple count using the CESD-10 set of items.

Our estimated relationships for these adult outcomes with our two childhood health index are presented in Table 6. We begin with the BMI related outcomes—being undernourished (BMI < 18.5), and being overweight (BMI > 25). High levels of undernourishment are common and widespread problems in low income countries in their pre-development phrase when food is scare, while being over-weight and sometimes obese becomes more common as societies grow richer and foods become more calorie intensive. In contrast to rich countries, within poor countries income or education both tend to be monotonically positive with BMI for men and inverse-U related for women (Strauss and Thomas 2008). The question we ask in these models is how our childhood health measures are associated with these inter-related BMI outcomes.

Table 6.

Estimates of Measures of Childhood Health on Under-nourishement, Overweight, Memory, and Depression (Robust standard errors in parenthesis below estimated coefficients)

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Undernourished (BMI < 18.5) | ||||||

| “Excellent”' or “V good” child health | -0.048** (0.020) | -0.046** (0.019) | -0.046** (0.019) | -0.016 (0.018) | -0.013 (0.017) | -0.005 (0.019) |

| height (cm) | 0.000 (0.001) | 0.000 (0.001) | 0.000 (0.001) | -0.000 (0.002) | 0.001 (0.002) | 0.001 (0.002) |

| Overweight (BMI > 25) | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.063** (0.025) | 0.059** (0.025) | 0.059** (0.025) | -0.023 (0.029) | -0.025 (0.030) | -0.039 (0.033) |

| height (cm) | 0.005** (0.002) | 0.005** (0.002) | 0.005** (0.002) | 0.007** (0.003) | 0.006** (0.003) | 0.003 (0.003) |

| Depression—CESD | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.756* (0.422) | -0.419 (0.391) | -0.395 (0.386) | -1.554*** (0.509) | -1.290*** (0.461) | -1.646*** (0.437) |

| height (cm) | -0.062* (0.035) | -0.077** (0.032) | -0.079** (0.034) | -0.098** (0.047) | -0.076* (0.038) | -0.034 (0.040) |

| Memory | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.029 (0.136) | 0.028 (0.131) | 0.037 (0.133) | 0.178 (0.131) | 0.169 (0.123) | 0.246* (0.128) |

| Height (cm) | 0.034*** (0.012) | 0.031** (0.012) | 0.029** (0.011) | 0.043*** (0.012) | 0.037*** (0.011) | 0.030** (0.013) |

Model (1) has controls for age group dummies only. Model (2) adds controls for urban-rural residence and province residence. Model (3) adds dummy variables for all communities.

Is statistically significant at one percent level

is statistically significant at five percent level:

is statistically significant at ten percent level.

Table 6 shows that estimated associations of childhood health with BMI are strong for men, but weaker for women. This is similar to patterns found with current SES variables and BMI, which is monotonically increasing for men but inverted u-shaped for women; Strauss et al. 2010). Among Chinese men, the childhood health subjective summary measures reduce the probability of being undernourished, while increasing the probability of being overweight. In contrast, these estimated associations are almost non-existent among Chinese women. The BMI dimension that appears to be related to adult height is being overweight for men and women, an indication that the pounds added in weight are proportionately higher than meters added in height.

There is a very strong relationship between poor childhood health using the five-point subjective scale and adult depression among Chinese women, but this estimated relationship is weaker among Chinese men. This result closely parallels that found by Smith and Smith (2010) in the U.S. context where the same retrospective childhood health index strongly predicted adult depression among middle aged and older Americans. This suggests that in evaluating their childhood health CHARLS respondents appear to be taking into account not only their physical health during their childhood years but their mental health as well. Taller Chinese men and women also appear to be less depressed as adults. Depression among Chinese women is very high and rises sharply with age (Strauss et al. 2010).

The final outcome examined in Table 6 is memory—the average of the immediate and delayed recall of ten words. Chinese men and women who are taller are estimated to have better memories and the same appears with the subjective child health scale for women but not for men. Since childhood health is related to better childhood nutrition, this may indicate that better childhood nutrition also improves adult memory (see for instance, Miguel and Glewwe 2008 and Strauss and Thomas 2008). Case and Paxson (2008) also report strong associations of adult height and cognition in the American context.

Table 7 summarizes the results obtained for these same adult outcomes when the models are estimated separately for the two CHARLS Pilot provinces. The strong overall male BMI results from Table 6 are now revealed to represent a reduction in undernourishment in the poorer agricultural Gansu province (true for women as well) and an increase in overweight in the richer Zhejiang province. The strong reduction in depression among Chinese women associated with poor childhood health on the five point scale is true in both of the provinces, but is clearly much largely in less economically advantaged Gansu. The female memory associations are also stronger in Gansu but exist in both provinces.

Table 7.

Estimates of Measures of Childhood Health on Undernourished, Overweight, Memory, and Depression by Province of Residence (Robust standard errors in parenthesis below estimated coefficients)

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhejiang | Gansu | difference | Zhejiang | Gansu | difference | |

| Undernourished (BMI < 18.5) | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.031 (0.020) | -0.064* (0.032) | -0.035 (0.037) | 0.049** (0.023) | -0.060** (0.027) | -0.105*** (0.035) |

| height (cm) | 0.001 (0.001) | -0.000 (0.002) | -0.002 (0.002) | 0.004* (0.002) | -0.003 (0.002) | -0.003 (0.003) |

| N | 470 | 409 | 482 | 387 | ||

| Overweight (BMI > 25) | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.073** (0.033) | 0.050 (0.035) | -0.027 (0.046) | -0.063 (0.041) | -0.014 (0.053) | 0.051 (0.067) |

| height (cm) | 0.005 (0.003) | 0.001 (0.003) | -0.003 (0.004) | 0.004 (0.004) | 0.002 (0.005) | -0.002 (0.006) |

| N | 470 | 409 | 482 | 387 | ||

| Depression—CESD | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.136 (0.376) | -0.716 (0.671) | -0.558 (0.767) | -0.916** (0.394) | -2.538*** (0.893) | -1.638* (0.964) |

| height (cm) | -0.043 (0.039) | -0.111** (0.054) | -0.055 (0.065) | -0.043 (0.042) | -0.023 (0.082) | 0.001 (0.089) |

| N | 424 | 365 | 416 | 307 | ||

| Memory | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.040 (0.194) | 0.050 (0.179) | 0.012 (0.267) | 0.031 (0.163) | 0.491** (0.188) | 0.458* (0.250) |

| height (cm) | 0.019 (0.017) | 0.036** (0.015) | 0.012 (0.023) | 0.029* (0.016) | 0.032 (0.021) | -0.004 (0.023) |

| N | 382 | 332 | 365 | 267 | ||

Is statistically significant at one percent level

is statistically significant at five percent level

is statistically significant at ten percent level. Community fixed effects are included.

Children with poor health in the much poorer Gansu province have less opportunity to get proper treatments, and less chance of getting proper education than those in Zhejiang. Thus, children with poor health have higher probabilities of staying in poor physical health in adulthood and in lower social economic status than those in Zhejiang. Both these factors may lead to higher depression in adulthood.

4.3 Empirical Estimates—Adult Health Behaviors

We have seen in the previous sections that especially among Chinese women there were statistically strong relationships between their health during childhood and their adult health, and especially among Chinese men their adult BMI. In this section, we address some possible behavioral mechanisms through which these outcomes may evolve. With that in mind, Table 8 examines these relationships using a few common health behaviors as the outcomes in order to understand the possible pathways that may exist in affecting adult health. Neither heavy adult drinking or smoking appear to be related to either measure of childhood health. This is certainly not surprising for women since both alcohol consumption and smoking are extremely rare among Chinese women. These health behaviors are not uncommon among men, but we still find little connection between male childhood health and these health behaviors.

Table 8.

Estimates of Measures of Childhood Health on Health Behaviors (Robust standard errors in parenthesis below estimated coefficients)

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Ever smoked | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.028 (0.036) | 0.019 (0.036) | 0.014 (0.035) | 0.002 (0.012) | 0.002 (0.012) | 0.003 (0.012) |

| height (cm) | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.004* (0.002) | 0.004* (0.002) | -0.000 (0.001) | -0.000 (0.001) | -0.000 (0.001) |

| Drinking | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.063 (0.039) | 0.045 (0.038) | 0.049 (0.039) | -0.004 (0.024) | -0.008 (0.023) | 0.019 (0.022) |

| height (cm) | 0.002 (0.003) | 0.003 (0.003) | 0.003 (0.003) | -0.000 (0.002) | -0.000 (0.002) | -0.001 (0.002) |

| Hours of vigorous exercise | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.433* (0.236) | -0.358 (0.231) | -0.372 (0.225) | -0.117 (0.181) | -0.004 (0.176) | -0.115 (0.175) |

| height (cm) | -0.035** (0.014) | -0.030** (0.015) | -0.021 (0.016) | -0.014 (0.016) | 0.001 (0.015) | 0.011 (0.014) |

| Hours of moderate exercise | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.387** (0.165) | -0.343** (0.169) | -0.395** (0.183) | 0.434** (0.176) | 0.495*** (0.172) | 0.425** (0.173) |

| height (cm) | -0.028** (0.014) | -0.027* (0.014) | -0.016 (0.015) | -0.008 (0.018) | -0.002 (0.018) | -0.005 (0.018) |

| Hours of moderate exercise—Gansu | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.045 (0.224) | -0.041 (0.230) | -0.192 (0.272) | 0.413 (0.296) | 0.443 (0.296) | 0.287 (0.306) |

| height (cm) | -0.032 (0.022) | -0.027 (0.023) | 0.001 (0.021) | -0.019 (0.029) | -0.011 (0.029) | 0.026 (0.028) |

| Hours of moderate exercise—Zhejiang | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.635** (0.244) | -0.658*** (0.245) | -0.608** (0.250) | 0.501** (0.205) | 0.520** (0.202) | 0.543*** (0.195) |

| height (cm) | -0.031* (0.018) | -0.027 (0.018) | -0.032 (0.020) | 0.001 (0.023) | 0.005 (0.022) | -0.028 (0.020) |

Model (1) has controls for age group dummies only. Model (2) adds controls for urban-rural residence and province residence. Model (3) adds dummy variables for all communities.

Is statistically significant at one percent level

is statistically significant at five percent level

is statistically significant at ten percent level.

The one adult health behavior that does appear to be related to childhood health is hours per day engaged in moderate and vigorous exercise, and once again coefficients are quite different for men and women. Taller men and those who self-report in good or excellent health as children are less likely to engage in vigorous or moderate exercise as adults. For women, these patterns are not statistically significant for vigorous exercise and the reverse sign or moderate exercise where women in excellent or very good health are actually take part in more hours of moderate exercise.

The last two panels in Table 8 present separate estimates of the moderate exercise models for the two provinces—Zhejiang and Gansu. The disparate male and female associations are clearly concentrated in Zhejiang, the economically dynamic province, and are not statistically significant in Gansu. This may have to do with the nature of work by gender. As part of their better economic opportunities with rapid economic development in Zhejiang, taller men and men with better childhood health may be active in more financially lucrative occupations that were at the same time much more sedentary than the occupations they would have been engaged in traditional China.

4.4 Empirical Estimates—Economic Outcomes

To this point, we have examined health outcomes and health behaviors that may be related to these health outcomes. In this sub-section, we summarize our results concerning the relationship between our measures of childhood health and the principal economic resource related outcomes that are available in the CHARLS Pilot survey. As explained above, the three main economic outcomes are the logarithms of per capita expenditures (Log PCE), income (Log income), and wealth (Log wealth). While all three outcomes capture some element of the economic resources available to the individual, the best overall measure is the Log PCE. We also examine the relationships with the level of completed schooling (some primary, completed primary, and junior high school and above).

Using the same format as used for adult health outcomes in Table 4, Table 9 summarizes estimated associations obtained for these three economic outcomes. Once again, separate models were estimated for Chinese men and for Chinese women. Estimated associations for the two provinces separately are available in Table 10.

Table 9.

Estimates of Measures of Childhood Health on Economic Outcomes (Standard errors in parenthesis below estimated coefficients)

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Log PCE | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.145** (0.068) | 0.087 (0.073) | 0.072 (0.089) | -0.009 (0.078) | -0.056 (0.071) | -0.035 (0.073) |

| height (cm) | 0.014*** (0.005) | 0.015*** (0.004) | 0.009* (0.005) | 0.025*** (0.009) | 0.019** (0.008) | 0.012 (0.008) |

| F-test for both (p-value) | 5.49*** (0.006) | 5.81*** (0.004) | 1.66 (0.195) | 4.39** (0.015) | 3.43** (0.037) | 1.39 (0.255) |

| Log income | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.058 (0.169) | -0.085 (0.164) | -0.120 (0.156) | 0.213 (0.166) | 0.094 (0.159) | 0.064 (0.161) |

| height (cm) | 0.040*** (0.014) | 0.043*** (0.013) | 0.026* (0.013) | 0.049*** (0.016) | 0.036** (0.015) | 0.019 (0.013) |

| F-test for both (p-value) | 4.54** (0.013) | 5.29*** (0.007) | 1.92 (0.152) | 5.38*** (0.006) | 3.13** (0.048) | 1.02 (0.363) |

| Log wealth | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.353 (0.238) | 0.163 (0.213) | 0.211 (0.227) | 0.224 (0.248) | 0.050 (0.225) | 0.140 (0.228) |

| height (cm) | 0.027* (0.014) | 0.032** (0.015) | 0.027* (0.013) | 0.072*** (0.019) | 0.054*** (0.018) | 0.032 (0.020) |

| F-test for both (p-value) | 3.38** (0.038) | 3.05* (0.052) | 3.11** (0.049) | 7.20*** (0.001) | 4.45** (0.014) | 1.43 (0.245) |

| Education (ordered probit) | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.144 (0.089) | -0.137 (0.091) | -0.148 (0.099) | -0.063 (0.087) | -0.105 (0.087) | -0.008 (0.100) |

| height (cm) | 0.028*** (0.006) | 0.026*** (0.006) | 0.025*** (0.006) | 0.032*** (0.008) | 0.026*** (0.008) | 0.019** (0.008) |

| F-test for both (p-value) | 14.14*** (0.000) | 13.01*** (0.000) | 10.45*** (0.000) | 8.97*** (0.000) | 6.39*** (0.003) | 2.71* (0.072) |

Model (1) has controls for age group dummies only. Model (2) adds controls for urban-rural residence and province residence. Model (3) adds dummy variables for all communities.

Is statistically significant at one percent level

is statistically significant at five percent level:

is statistically significant at ten percent level.

Table 10.

Estimates of Measures of Childhood Health on Economic Outcomes by Province (Standard errors in parenthesis below estimated coefficients)

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhejiang | Gansu | difference | Zhejiang | Gansu | difference | |

| Log PCE | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.184** (0.089) | -0.047 (0.158) | -0.228 (0.187) | -0.038 (0.073) | -0.033 (0.135) | 0.002 (0.149) |

| height (cm) | 0.012** (0.005) | 0.006 (0.009) | -0.008 (0.009) | 0.005 (0.009) | 0.022 (0.013) | 0.012 (0.015) |

| N | 470 | 408 | 483 | 387 | ||

| Log income | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.391 (0.300) | 0.038 (0.343) | -0.352 (0.448) | -0.037 (0.314) | 0.311 (0.347) | 0.351 (0.463) |

| height (cm) | 0.036** (0.017) | 0.017 (0.020) | -0.010 (0.026) | 0.057*** (0.020) | -0.005 (0.037) | -0.054 (0.036) |

| N | 470 | 408 | 483 | 387 | ||

| Log wealth | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | 0.391 (0.300) | 0.038 (0.343) | -0.352 (0.448) | -0.037 (0.314) | 0.311 (0.347) | 0.351 (0.463) |

| height (cm) | 0.036** (0.017) | 0.017 (0.020) | -0.010 (0.026) | 0.057*** (0.020) | -0.005 (0.037) | -0.054 (0.036) |

| N | 470 | 408 | 483 | 387 | ||

| Education (ordered probit) | ||||||

| “Excellent” or “V good” child health | -0.155 (0.130) | -0.153 (0.151) | -0.027 (0.200) | -0.018 (0.126) | 0.051 (0.168) | 0.043 (0.212) |

| height (cm) | 0.019** (0.009) | 0.029*** (0.008) | 0.022* (0.012) | 0.011 (0.010) | 0.032** (0.014) | 0.037** (0.018) |

| N | 470 | 409 | 483 | 387 | ||

Is statistically significant at one percent level

is statistically significant at five percent level:

is statistically significant at ten percent level. Community fixed effects are included.

There are several salient patterns. In general, these adult economic outcomes are more strongly related to adult height than they are to the subjective child health index. Compared to the health related outcomes described above, these economic outcomes are also more sensitive to region-urban controls and particularly to community fixed effects controls which both tend to weaken estimated coefficients of either measure of childhood health. In terms of the estimated magnitude of the coefficients for adult height, the estimated associations of being taller appear to be positive across all three measures of economic resources and actually are a bit larger for women compared to men. Using the first model in Table 9, being in excellent or very good health as a child is associated with a 15 percent increase in Log PCE for men, about the same as an extra ten centimeters in male height. Among Chinese women, the effects of childhood health are not statistically significant but an additional centimeter in height adds 2.5 percent to log PCE.

The final panel in Table 9 examines the estimated associations with years of education completed using order probit models for the four education categories in Table A.1 (illiterate, can read or write, finished primary, and middle school and above). There is little apparent relationship of the childhood subjective summary index which parallels results obtained by Smith for the United States (Smith 2009b). However, adult height is strongly related to years of schooling completed. Boys and girls who grow up to be taller also have more schooling than their shorter contemporaries, a result also obtained by Case et al. (2005) for the United States. Table 10 shows that these associations tend to be stronger in Zhejiang compared to Gansu.

These results parallel those of Case and Paxson (2008) for the United States. They also find strong associations of height with earnings and education and also find strong associations of height with cognitive ability as we did for memory. Their interpretation that improved cognitive ability represents a major pathway to better education and adult economic performance may be equally true for China.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we studied the consequences of childhood health on adult health and adult SES outcomes in China using a new sample of middle aged and older Chinese respondents. Modeled after the American HRS, the CHARLS Pilot survey respondents are 45 years and older in two quite geographically and economically distinct provinces—Zhejiang a high growth industrialized province on the East Coast and Gansu, a largely agricultural and poor province in the West. Our work on childhood health in CHARLS relied on two complementary measures that proxy for different dimensions of health during the childhood years. The first is a retrospective self-evaluation using a standard five-point scale (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor) of the general state of health when one was less than 16 years old. The second is adult height thought to be a good measure of levels of nutrition during early childhood and the prenatal period. We related both these childhood health measures to adult health and SES outcomes during the adult years. We find strong associations of childhood health on adult health outcomes particularly among Chinese women and strong associations on adult BMI particularly for Chinese men. Turning to the best measure of economic resources available to the family Log PCE, we find strong associations of adult height for both men and women with Log PCE.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and Natural Science Foundation of China.

Appendix

Table A.1.

Summary sample statistics for all the variables

| Men |

Women |

All |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | |

| Aged 45-54 | 0.37 | (0.48) | 879 | 0.42 | (0.49) | 870 | 0.39 | (0.49) | 1749 |

| Aged 55-64 | 0.35 | (0.48) | 879 | 0.33 | (0.47) | 870 | 0.34 | (0.47) | 1749 |

| Aged 65-74 | 0.22 | (0.41) | 879 | 0.18 | (0.38) | 870 | 0.20 | (0.40) | 1749 |

| Aged 75+ | 0.07 | (0.25) | 879 | 0.08 | (0.27) | 870 | 0.07 | (0.26) | 1749 |

| Illiterate | 0.25 | (0.43) | 879 | 0.62 | (0.48) | 870 | 0.44 | (0.50) | 1749 |

| Can read or write | 0.24 | (0.43) | 879 | 0.16 | (0.36) | 870 | 0.20 | (0.40) | 1749 |

| Finished primary | 0.25 | (0.43) | 879 | 0.11 | (0.31) | 870 | 0.18 | (0.38) | 1749 |

| Middle school and above | 0.26 | (0.44) | 879 | 0.11 | (0.31) | 870 | 0.18 | (0.39) | 1749 |

| Rual | 0.60 | (0.49) | 879 | 0.55 | (0.50) | 870 | 0.57 | (0.49) | 1749 |

| Gansu | 0.47 | (0.50) | 879 | 0.44 | (0.50) | 870 | 0.46 | (0.50) | 1749 |

| Ln PCE | 8.44 | (0.98) | 878 | 8.38 | (1.13) | 870 | 8.41 | (1.06) | 1748 |

| Ln income | 7.91 | (2.32) | 878 | 7.90 | (2.30) | 870 | 7.91 | (2.31) | 1748 |

| Ln wealth | 8.86 | (3.17) | 878 | 8.77 | (3.26) | 870 | 8.82 | (3.21) | 1748 |

| “Excellent” or “Very good” child health | 0.69 | (0.46) | 879 | 0.65 | (0.48) | 870 | 0.67 | (0.47) | 1749 |

| Height (cm) | 164.1 | (6.7) | 879 | 153.0 | (6.1) | 870 | 158.6 | (8.5) | 1749 |

| Poor adult health | 0.23 | (0.42) | 877 | 0.32 | (0.47) | 868 | 0.27 | (0.45) | 1745 |

| Hypertensive | 0.38 | (0.49) | 879 | 0.49 | (0.50) | 869 | 0.44 | (0.50) | 1748 |

| Undiagnosed hypertension | 0.53 | (0.50) | 335 | 0.44 | (0.50) | 425 | 0.47 | (0.50) | 760 |

| ADLs | 0.14 | (0.54) | 871 | 0.20 | (0.65) | 863 | 0.17 | (0.60) | 1734 |

| IADLs | 0.35 | (0.89) | 810 | 0.74 | (1.29) | 788 | 0.54 | (1.12) | 1598 |

| Prob not survive to age 75 | 0.26 | (0.44) | 583 | 0.29 | (0.45) | 596 | 0.27 | (0.45) | 1179 |

| BMI | 22.3 | (3.0) | 879 | 23.6 | (3.6) | 869 | 22.9 | (3.4) | 1748 |

| Undernourished (BMI<18.5) | 0.06 | (0.25) | 879 | 0.07 | (0.26) | 869 | 0.07 | (0.25) | 1748 |

| Overweight (BMI>25) | 0.19 | (0.39) | 879 | 0.33 | (0.47) | 869 | 0.26 | (0.44) | 1748 |

| Depression - CESD | 7.50 | (5.82) | 789 | 8.76 | (6.26) | 723 | 8.10 | (6.07) | 1512 |

| Memory | 3.50 | (1.71) | 714 | 3.26 | (1.78) | 632 | 3.38 | (1.75) | 1346 |

| Ever smoked | 0.67 | (0.47) | 879 | 0.02 | (0.15) | 870 | 0.35 | (0.48) | 1749 |

| Heavy drinker | 0.19 | (0.39) | 876 | 0.02 | (0.15) | 869 | 0.11 | (0.31) | 1745 |

| Vigorous exercise (hours/day) | 2.78 | (3.07) | 876 | 1.37 | (2.53) | 868 | 2.08 | (2.90) | 1744 |

| Moderate exercise (hours/day) | 2.45 | (2.70) | 870 | 2.55 | (2.67) | 856 | 2.50 | (2.69) | 1726 |

Note: For each variable, the sample is restricted to observations who take nonmissing values in that variable and all the regressors in Table 4.

Footnotes

Paper originally presented at a Festschrift in Honor of T. Paul Schultz.

The term Pilot is used since the survey in these two Chinese provinces was used to help prepare for the national level survey in 2011. However, it is not a pilot in the traditional use of that term since these households in the ‘pilot’ will be revisited in a second panel wave in 2012.

In situations where more than one age-eligible household lives in a dwelling unit, CHARLS randomly selected one and then determined the number of age-eligible members within a household and then randomly selected one.

Most non-government surveys in China do not publish baseline response rates and government survey reports are thought to be unreliable. Non-retention rates between waves in the China Health and Nutrition Survey averaged between 12% and 20% (Popkin et. al. 2010).

Individual agricultural income is constructed in the following steps: We first count the number of household members who engage in agriculture based on the information from the survey and then calculate each individual's share in the household agriculture income using the above calculated number as the denominator. For example, if a household has five household members and three of them reported that they engaged in agricultural activities. Then each of the three members takes 1/3 share of the household net agricultural income while the remaining two individuals take no share in individual agricultural income. The individual self-employment income is constructed similarly. We first find out the number of family members who engage in self-employment activities, and then average self-employment income among those engaged in self-employment activities equally (as no further information to help us identify the specific shares).

The rural definition we use in this paper is the State Bureau of Statistics (SBS) definition. Some of the SBS urban communities are in fact rural in nature and many of their populations are farmers with agricultural hukou.

In a few cases there was no variation in the dependent variable among observations within the PSU. In these cases we refined the PSU to be a more aggregate area, usually the county or city.

ADLs include difficulty in dressing, bathing and showering, eating, getting in and out of bed, using the toilet and controlling urination and defecation.

IADLs include difficulties with household chores, preparing hot meals, shopping for groceries, managing money, making phone calls, and taking medications.

CHARLS contains no measures of general optimism or pessimism which would be useful for these subjective measures.

References

- Banks James, Oldfield Zoe, Smith James P. NBER Working Paper no. 17096. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2011. Childhood Health and Differences in Late Life Outcomes between England and America. [Google Scholar]

- Barker David J. P. Maternal Nutrition, Fetal Nutrition and Diseases in Later Life. Nutrition. 1997;13(9):807–13. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(97)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case Anne, Paxson Christina. Stature and Status: Height, Ability, and Labor Market Outcomes. Journal of Political Economy. 2008;116(3):499–532. doi: 10.1086/589524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case Anne, Fertig Angela, Paxson Christina. The Lasting Impact of Childhood Health and Circumstance. Journal of Health Economics. 2005;24(2):365–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case Anne, Lubotsky Darren, Paxson Christina. Economic Status and Health in Childhood: The Origins of the Gradient. American Economic Review. 2002;92(5):1308–34. doi: 10.1257/000282802762024520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie Janet, Stabile Michael. Socioeconomic Status and Child Health—Why is the Relationship Stronger for Older Children? American Economic Review. 2003;93(5):1813–23. doi: 10.1257/000282803322655563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie Allison, Shields Michael, Price Stephen. IZA Discussion Paper no. 1328. Bonn; Germany: 2004. Is the Child Health/Income Gradient Universal? Evidence from England. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney Liam, McGovern Mark, Smith James P. From Angela's Ashes to the Celtic Tiger—Early Life Conditions and Adult Health in Ireland. Journal of Health Economics. 2011;30(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel Robert. The Escape from Hunger and Premature Death: 1700-2100. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman Alissa, Joyce Robert, Smith James P. The Long Shadow Cast by Physical and Mental Problems on Adult Life. PNAS; Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences. 2011;1108(15):6032–37. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016970108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habicht Jean-Pierre, Martorell Reynaldo, Rivera Juan. Nutritional Impact of Supplementation in the INCAP Longitudinal Study: Analytical Strategies and Influences. Journal of Nutrition. 1995;125(4S):1042S–50S. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.suppl_4.1042S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott John, Maluccio John, Behrman Jere R., Flores Rafael, Martorell Reynaldo. The Effect of a Nutrition Intervention During Early Childhood on Economic Productivity in Guatemalan Adults. Lancet. 2008;371(9610):411–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maluccio John, Hoddinott John, Behrman Jere R., Martorell Reynaldo, Quisumbing Agnes, Stein Aryeh. The Impact of Improving Nutrition During Early Childhood on Education Among Guatemalan Adults. Economic Journal. 2008;119(537):734–63. [Google Scholar]

- Martorell Reynaldo, Habicht Jean-Pierre. Growth in Early Childhood in Developing Countries. In: Falkner F, Tanner JM, editors. Human Growth. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Plenum Press; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Miguel Edward, Glewwe Paul. The Impact of Child Health and Nutrition on Education in Less Developed Countries. In: Schultz TP, Strauss J, editors. Handbook of Development Economics. Vol. 4. North Holland Press; Amsterdam: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oreopoulos Phil, Stabile Mark, Walld Rand, Roos Leslie. NBER Working Paper no. 11998. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2006. Short, Medium, and Long-Term Consequences of Poor Infant Health: An Analysis Using Siblings and Twins. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin Barry M., Du Shufa, Zhaqi Fengying, Zhang Bing. Cohort Profile: The China Health and Nuitrition Survey—Monitoring and Understanding Socio-economic and Health Change in China, 1989-2011. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;39(6):1435–40. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith James P. Healthy Bodies and Thick Wallets. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1999;13(2):145–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith James P. Reconstructing Childhood Health Histories. Demography. 2009a;46(2):387–403. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith James P. The Impact of Childhood Health on Adult Labor Market Outcomes. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2009b;91(3):478–89. doi: 10.1162/rest.91.3.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith James P., Smith Gillian C. Long-Term Economic Costs of Psychological Problems during Childhood. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;71(1):110–15. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckel Richard. Stature and the Standard of Living. Journal of Economic Literature. 1995;33(4):1903–40. [Google Scholar]

- Steckel Richard. Biological Measures of the Standard of Living. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2008;22(1):129–52. doi: 10.1257/jep.22.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss John, Thomas Duncan. Human Resources: Empirical Modeling of Household and Family Decisions. In: Behrman JR, Srinivasan TN, editors. Handbook of Development Economics. 3A. North Holland Press; Amsterdam: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss John, Thomas Duncan. Health, Nutrition and Economic Development. Journal of Economic Literature. 1998;36(3):766–817. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss John, Thomas Duncan. Health over the Life Course. In: Schultz TP, Strauss J, editors. Handbook of Development Economics. Vol. 4. North Holland Press; Amsterdam: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss John, Lei Xiaoyan, Park Albert, Shen Yan, Smith James P, Yang Zhe, Zhao Yaohui. Health Outcomes and Socio-Economic Status Among the Elderly in China: Evidence from the CHARLS Pilot. Journal of Population Ageing. 2010;3(3-4):111–42. doi: 10.1007/s12062-011-9033-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth Michael, Kuh Diana. Childhood Influences on Adult Health: A Review of Recent Work from the British 1946 National Birth Cohort Study, the MRC National Survey of Health and Development. Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 1997;11(1):2–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1997.d01-7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Yaohui, Strauss John, Park Albert, Sun Yan. Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study-Pilot. Users Guide. National School of Development, Peking University; Peking: 2009. [Google Scholar]