Abstract

Poor psychological outcomes are common among trauma survivors, yet not all survivors experience adverse sequelae. The current study examined links between cumulative trauma exposure as a function of the level of betrayal (measured by the relational closeness of the survivor and the perpetrator), trauma appraisals, gender, and trauma symptoms. Participants were 273 college students who reported experiencing at least one traumatic event on a trauma checklist. Three cumulative indices were constructed to assess the number of different types of traumas experienced that were low (LBTs), moderate (MBTs), or high in betrayal (HBTs). Greater trauma exposure was related to more symptoms of depression, dissociation, and PTSD, with exposure to HBTs contributing the most. Women were more likely to experience HBTs than men, but there were no gender differences in trauma-related symptoms. Appraisals of trauma were predictive of trauma-related symptoms over and above the effects explained by cumulative trauma at each level of betrayal. The survivor’s relationship with the perpetrator, the effect of cumulative trauma, and their combined impact on trauma symptomatology are discussed.

Keywords: cumulative trauma, betrayal, appraisals, gender, trauma symptomatology

Exposure to traumatic events is frequently linked to poor psychological outcomes, including depression, dissociation, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Briere & Jordan, 2009; Gillespie et al., 2009; Greif Green et al., 2010). Yet symptom severity and duration vary greatly among trauma survivors from minimal or no adverse reactions to short-term or chronic symptomatology (Breslau, 2009; Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005). To better understand symptom variability and inform interventions aimed at mitigating persistent, adverse reactions to traumatic events, much research has focused on identifying the trauma-related factors that best predict negative mental health outcomes. Greater frequency, severity, and duration typically result in worse outcomes, but when examined across studies, the magnitude with which these factors impact psychological outcomes varies (as reviewed by Briere & Jordan, 2009). These inconsistencies highlight the nuanced and multidimensional nature of trauma and its sequelae, suggesting the possibility that additional factors be considered. The present study extends the literature by considering the cumulative effect of different types of trauma. In particular, we consider the role of interpersonal relationships and betrayal. We also examine the survivors’ appraisals of trauma and gender differences as predictors of depression, dissociation, and PTSD symptoms. We review the literature for each of these potential contributing factors below.

Trauma Characteristics and Related Outcomes

Cumulative Trauma Exposure

Many studies in the maltreatment literature focus on single types of trauma (e.g., only sexual abuse/assaults, neglect, or interpersonal violence; Finkelhor, Ormond, & Turner, 2007a; 2007b). Such studies may not account for the impact of other types of traumas experienced by participants, and consequently may overestimate the effects of the singular type of trauma examined (Saunders, 2003). When studies include more than one type of trauma, the majority of trauma survivors report exposure to multiple categories of trauma (Arata, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Bowers, & O’Farrill-Swails, 2005; Dong et al., 2004; Edwards, Holden, Felitti, & Anda, 2003; Finkelhor et al., 2007a; 2007b; Greif Green et al., 2010). Moreover, compared with survivors exposed to a single trauma type, survivors of multiple trauma types, particularly adverse childhood events (ACEs), are more likely to experience chronic psychological and health problems, such as depression, anxiety, aggression, sleep disturbance, severe obesity, somatic complaints, and substance abuse (Anda et al., 2006; Arata et al., 2005; Edwards et al., 2003; Finkelhor et al., 2007a; 2007b; Greif Green, 2010). These studies suggest that it is not merely the number of traumatic events experienced, but the number of unique types of trauma experienced that contributes to negative outcomes.

In the current study, “cumulative trauma” refers to the number of different trauma types (and not the total number of traumatic incidents) experienced. In this sense, someone who was sexually abused several times, by one or more perpetrators, but who experienced no other trauma types would be defined as having a single trauma type; whereas, someone who was both sexually and physically abused, regardless of the frequency or number of perpetrators, would be defined as having multiple trauma types (i.e., 2), and thus, cumulative trauma.

Cumulative trauma is an important predictor of trauma and health-related outcomes. The impact of any unique trauma, among multiple types, is less clear. Some work suggests that the individual contribution of a single trauma type to the severity of outcomes is reduced when the cumulative trauma is considered (Finkelhor et al., 2007a). However, Greif Green and colleagues (2010) found a differential impact for traumatic events considered to be maladaptive to family functioning (i.e., child sexual abuse, family violence) when examining the effects of cumulative trauma. They found that increases in cumulative trauma considered maladaptive to family functioning were more predictive of psychological distress than similar increases in other types of adverse events (i.e., parental death). Similarly, in a study examining the effects of ACEs, Edwards and her colleagues (Edwards, Freyd, Dube, Anda, & Felitti, accepted pending minor revisions) found that survivors of child sexual abuse experienced more adverse events and worse physical and psychological outcomes in adulthood when their abuser was someone with whom they shared a close relationship. Thus, it might be that in contrast to any single trauma type, traumas considered maladaptive to family functioning, such as interpersonal traumas perpetrated by someone with whom a close relationship was shared, might differentially influence trauma-related symptomatology.

Betrayal

The trauma survivor’s relationship to the perpetrator is an established predictor of trauma-related psychopathology, with interfamilial or interpersonal traumas being associated with more negative psychological outcomes than extrafamilial or noninterpersonal traumas (Cromer & Smyth, 2010; Freyd, Klest, & Allard, 2005; Lawyer, Ruggiero, Resnick, Kilpatrick, & Saunders, 2006). Betrayal trauma theory (Freyd, 1996) offers one possible explanation to account for these differences. Founded in attachment theory, betrayal trauma theory proposes that trauma that is perpetrated by a trusted or depended upon other (i.e., a high betrayal trauma) is more psychologically damaging than trauma perpetrated by a nonclose other, or noninterpersonal traumas. The concurrent states of dependence and abuse are at odds with one another, creating a conflict for the victim between the need to stay engaged in a relationship and the need to defend oneself. According to betrayal trauma theory, betrayal awareness is suppressed when survival and attachment are at stake. In order to obtain basic needs (e.g., food, shelter, or attachment), the victim will attempt to maintain a relationship with the perpetrator, potentially resulting in unawareness of the trauma and/or self-blame. This puts victims at long-term risk for mental health problems. Not surprisingly, survivors of traumas high in betrayal experience greater depression, dissociative tendencies, and posttraumatic stress compared to low betrayal traumas (Freyd et al., 2005; DePrince, 2005; Tang & Freyd, in press). Because of the distinct impact of high betrayal traumas compared to traumas low in betrayal, level of betrayal may categorically distinguish the differential impact of different types of trauma.

Trauma Appraisals

Theoretical models have posited the role of cognitive appraisals as mediators in the development and persistence of trauma-related psychopathology (Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Foa, Stekette, & Rothbaum, 1989). Appraisals include survivors’ assessments of their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in response to trauma exposure (e.g., assessment of presence and severity of self-blame; see DePrince, Chu, & Pineda, in press). Evidence suggests that negative appraisals account for symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress beyond amount and severity of trauma among survivors of interpersonal and noninterpersonal traumas (e.g., Andrews, Brewin, Rose, & Kirk, 2000; Cromer & Smyth, 2010; DePrince et al., in press; Ellis, Nixon, & Williamson, 2009; Fairbrother & Rachman, 2006). Thus, the manner in which trauma survivors evaluate their experiences of trauma appears to impact trauma symptoms, above and beyond objective factors.

Gender

Gender is consistently linked to depression and PTSD in trauma survivors. Although men typically report being exposed to more traumatic events than do women, women generally have higher prevalence rates of PTSD (Breslau, 2009). Similarly, there are disparate prevalence rates for major depressive disorder between women and men, with women more often manifesting depressive symptoms than men (Kessler, McGonagle, Swartz, Blazer, & Nelson, 1993). These varying gender outcomes might result from differences in the types of traumatic events experienced or the strategies used to overcome them (as reviewed by Accortt, Freeman, & Allen, 2008). For example, women tend to experience significantly more interpersonal trauma (Barlow & Cromer, 2006; Gavranidou & Rosner, 2003; Goldberg & Freyd, 2006). In a recent study, Tang and Freyd (in press) found that increased PTSD symptoms for women were partially mediated by traumatic experiences perpetrated by someone with whom the survivor shared a close relationship (i.e., high betrayal trauma). These findings suggest that there may be gender differences in the types of trauma experienced and that worse outcomes in women is predicted by their higher levels of exposure to trauma higher in betrayal.

Current Study

The present study was designed to examine links between cumulative trauma within relationally-specific categories of trauma [defined as low (LBT), moderate (MBT), and high betrayal trauma (HBT)], trauma-related appraisals, gender, and trauma symptomatology. In line with previous research (Goldberg & Freyd, 2006; Tang & Freyd, in press), we hypothesized that women trauma survivors would report experiencing (Hypothesis 1a) more HBTs and (1b) more depression and PTSD symptoms than men (Accortt et al., 2008; Breslau, 2009). We further hypothesized (1c) that HBTs would account for the relationship between gender and symptomatology. We hypothesized (2a) that increases in the number of traumas experienced would be predictive of depression, dissociation, and PTSD symptoms, and (2b) that the cumulative effects of trauma would better predict trauma-related symptoms as the level of betrayal increased. Moreover, we predicted that (3) trauma appraisals would contribute to outcomes of trauma over and above the effects explained by cumulative trauma at each level of betrayal. We similarly expected that (4) increases in cumulative trauma, would be associated with stronger appraisals, where HBTs would be the most predictive, followed by MBTs and LBTs, respectively.

Method

Participants

Participants were 468 college students enrolled in an introductory-level psychology course at a university in the northwestern United States. Participants were recruited by way of an online research management system and received course credit for participating. The current study included 273 students who endorsed having experienced at least one traumatic event on a trauma checklist. Ten participants were excluded as a result of missing data and one participant was excluded for not identifying a gender. The participants included in the current study were mostly female (n =188, 69%) and were an average age of 20.36 years (SD = 3.99). The majority of participants identified as Caucasian (80%), 8% identified as Latino, 7% as multi-racial, 5% as Asian, 4% as other, 1% as Native American, and less than 1% declined to answer. Participants excluded from analyses were significantly younger in age (M = 19.61, SD = 2.63) than those included, t(463) = 2.31, p = .021, d = .218, but they did not differ by gender, χ2(1, N = 465) = 1.73, p = .189, ϕ = .061, or race, χ2(4, N = 463) = 3.53, p = .474, ϕc = .087.

Measures

Trauma Exposure and Betrayal

The Brief Betrayal Trauma Survey (BBTS; Goldberg & Freyd, 2006) is a 12-item self-report measure assessing the frequency and severity of betrayal—low betrayal trauma (LBT), moderate betrayal trauma (MBT), and high betrayal trauma—(HBT) for traumatic events that have occurred during childhood and adulthood. The level of betrayal pertains to the relational closeness of the trauma survivor to the perpetrator. Three LBT items assess traumas that are typically absent of trust or an interpersonal component such as natural disasters and accidents. Four MBT items assess interpersonal traumas that involve a personal or witnessed assault, but without the presence of a close, trusting relationship, such as a physical or sexual assault by a stranger. Three HBT items assess the prevalence of interpersonal traumas (e.g., physical, sexual, and emotional abuse) perpetrated by someone with whom a close relationship was shared. The BBTS has good construct validity (DePrince & Freyd, 2001) and test-retest reliability (Goldberg & Freyd, 2006), and a distinct difference in the severity of trauma sequelae between moderate and high betrayal trauma has been demonstrated (Tang & Freyd, in press).

To create cumulative trauma indices, the BBTS items were dichotomized (0 = never experienced and 1 = experienced at least once) and then summed within each level of betrayal. The temporal period in which the event occurred (i.e., childhood versus adulthood) did not augment the number of particular trauma types experienced (e.g., physical abuse categorized as an HBT experienced both in childhood and adulthood would only result in a single trauma type within the HBT index). In contrast to other indices of trauma (e.g., Anda et al., 2006; Finkelhor et al., 2007b), our index distinguishes between physical abuse perpetrated by a close other (i.e., a HBT) and physical abuse perpetrated by a nonclose other (i.e., a MBT), with each counted as a unique trauma type. Beyond relational closeness, the survivor perpetrator relationship was not assessed. Two BBTS items were not included in the current analyses because of low base rates: one asked about the death of a child and one was an open-ended question assessing traumatic events not evaluated in the measure.

Trauma Appraisals

The Trauma Appraisal Questionnaire (TAQ; DePrince, Zurbriggen, Chu, & Smart, 2010) is a 54-item self-report measure that examines self-evaluations of beliefs, emotions, and behaviors in relation to experienced traumatic events. Participants were asked how they currently think about the traumatic event they experienced. If participants reported experiencing more than one traumatic event, they were asked to think about the event that was most traumatic or had the most impact on their life. Responses are made on a Likert-scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The TAQ is comprised of six subscales: betrayal, self-blame, fear, alienation, anger, and shame, and it has been shown to have good convergent and discriminant validity and test-retest reliability (DePrince et al., 2010). The full scale score was used in the current analyses because the subscales were too highly correlated to reliably interpret differences in appraisal type. The coefficient alpha for the TAQ in the current sample was .97.

Depression and Dissociation Symptoms

The Trauma Symptom Checklist (TSC-40; Briere & Runtz, 1989) is a 40-item self-report measure that assesses trauma-related symptoms. For each symptom, respondents report its frequency during the prior two months using a Likert-type scale from 0 = never to 3 = often. The TSC is comprised of six subscales, of which, only the depression and dissociation subscales were used, based on our desire to examine these particular trauma sequelae in the current study. Scores on the depression subscale could range from 0 to 36 and from 0 to 18 on the dissociation subscale. The TSC-40 has good reliability and predictive validity (Briere, 1996). Coefficient alphas were .71 and .74 for the depression and dissociation subscales, respectively.

PTSD symptoms

The Revised Civilian Mississippi Scale for PTSD (RCMS; Norris & Perilla, 1996) is a 30-item self-report measure that assesses posttraumatic symptomatology. The first 18 items focus on symptoms related to a specific traumatic event, while the last 12 are not event specific. Responses are made on a Likert-scale ranging from 1 = not at all true to 5 = extremely true. The RCMS has good psychometric properties (Norris & Perilla, 1996), and the coefficient alpha for the current sample was .91.

Procedure

The University’s Office for the Protection of Human Subjects approved this study prior to any data collection. Participation in the study fulfilled part of the students’ course requirement. Participants did not self-select into the study based on knowledge of its content. Participants completed all study measures, consent and debriefing online.

Results

Trauma Exposure

A majority of participants experienced more than one type of trauma (63%), with over a quarter of all participants being exposed to four or more distinct trauma types (from a list of 10 types among the three levels of betrayal). Approximately 69% of participants experienced at least one LBT, 51% experienced at least one MBT, and 59% experienced at least one HBT. Bivariate Pearson correlation analyses (Table 1) further indicated that the number of unique types of LBTs was significantly correlated with the number of unique types of MBTs experienced, and likewise the number of unique types of MBTs and HBTs experienced were significantly correlated. Cumulative trauma at all three levels of betrayal was significantly correlated with depressive, dissociative, and PTSD symptoms. Other significant relationships were found between age and cumulative trauma, with older participants reporting more MBTs and HBTs. Gender was significantly correlated with HBTs but not to MBTs or LBTs. Gender was also significantly correlated with trauma appraisals. Neither gender nor age was associated with depression, dissociation, or PTSD symptoms, and minority status was not significantly associated with any variables of interest.

Table 1.

Correlations between Study Variables and Descriptive Statistics

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | — | |||||||||

| 2. Gender | .03 | — | ||||||||

| 3. Minority | .04 | .01 | — | |||||||

| 4. LBT | .10† | .00 | .03 | — | ||||||

| 5. MBT | .22*** | .02 | .11† | .25*** | — | |||||

| 6. HBT | .18** | .14* | .05 | .09 | .45*** | — | ||||

| 7. Appraisals | .08 | .13* | .02 | .11† | .43*** | .49*** | — | |||

| 8. Depression | .03 | .07 | .03 | .11† | .27*** | .31*** | .51*** | — | ||

| 9. Dissociation | .00 | .00 | .01 | .17** | .27*** | .29*** | .49*** | .64*** | — | |

| 10. PTSD | .10† | .10† | .03 | .20** | .37*** | .49*** | .73*** | .57*** | .51*** | — |

| Mean | 20.36 | 0.69 | 0.17 | 0.97 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 1.84 | 7.31 | 4.92 | 55.25 |

| SD | 3.97 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.83 | 1.07 | 0.94 | 0.77 | 4.49 | 3.41 | 15.50 |

| Range | 18–52 | 0–1 | 0–1 | 0–3 | 0–4 | 0–3 | 1–4.24 | 0–22 | 0–18 | 32–121 |

Note. Gender: male =1, female = 2; Minority: nonminority = 0, minority = 1; LBT is low betrayal trauma; MBT is moderate betrayal trauma; HBT is high betrayal trauma; PTSD is posttraumatic stress disorder; SD is standard deviation

< .10,

< .05,

< .01,

< .001

Examination of the descriptive statistics for the variables of interest revealed a positive skew for each variable (Table 1). Analyses were conducted with the raw, untransformed values and values derived from a square root transformation. These analyses produced analogous results, and for ease of interpretation, nontransformed data are reported herein.

Gender, Trauma, and Trauma-Related Symptoms

Independent samples t-tests were conducted to test our first set of hypotheses that (1a) women trauma survivors would report more HBTs than men and that (1b) women would report more symptoms of depression and PTSD. As predicted, women trauma survivors reported significantly more HBTs (M = 0.99, SD = 0.96) than men (M = 0.72, SD = 0.88), t(271) = −2.27, p = 0.02, d = 0.30. Although women experienced more MBTs (M = 0.88, SD = 1.05) than men (M = 0.82, SD = 1.11), differences were not significant, t(271) = −0.38, p = 0.70, d = 0.05. Gender differences were not found for LBTs, t(271) = −0.03, p = 0.98, d = 0.004, with women (M = 0.97, SD = 0.81) and men (M = 0.96, SD = 0.89) reporting equivocally. In contrast to our hypotheses, women did not have significantly more depression (M = 7.53, SD = 4.28) or PTSD (M = 56.32, SD = 15.98) than men (depression: M = 6.82, SD = 4.92; PTSD: M = 52.86, SD = 14.20); depression (t(271) = −1.20, p = 0.23, d = 0.16); PTSD (t(271) = −1.72, p = 0.09, d = 0.23). Given the lack of a statistically significant relationship between gender and depression and PTSD symptoms in this sample, the mediation analysis to examine the hypothesis that (1c) HBTs would account for the relationship between gender and symptomatology was not conducted.

Predicting Trauma-Related Symptoms

Multiple linear regression was used to test the hypothesis that cumulative trauma would be associated with greater trauma-related symptomatology, where HBTs would contribute the most to a regression model, followed by MBTs and LBTs. The cumulative trauma indices, by level of betrayal, were entered into the model simultaneously. The R (R Development Core Team, 2006) package relimp (Firth, 2006) was used to examine the relative importance of each cumulative trauma index according to Lindeman, Merenda, and Gold’s (1980) method (i.e., lmg). Lmg provides a natural decomposition of R2 by averaging the sums of squares of each predictor across all orderings, and is thus, a more accurate method for comparing relative importance when predictors are correlated than comparing standardized beta values (Grömping, 2006). An additional step, which included trauma appraisals, was added to the model to test the hypothesis that trauma appraisals would contribute to trauma outcomes over and above the effects of the other variables. Bivariate Pearson’s correlation coefficients were examined to determine whether the demographic variables would need to be controlled for in the regression analyses. Due to a lack of a statistically significant relationship between the demographic variables and the trauma symptoms, they were not controlled. Multicollinearity problems were assessed (Pedhazur, 1997), but none were found.

Depression

The cumulative trauma indices accounted for a significant amount of the variance in depression, adjusted R2 = .11, F(3, 269) = 11.86, p < .001. MBTs and HBTs, but not LBTs, were significant predictors, where increases in the number of these unique traumas were associated with increases in symptoms (Table 2). As predicted, HBTs contributed the most to the model, followed by MBTs and LBTs (lmgs = 0.07, 0.04, and < 0.01, respectively). Adding trauma appraisals to the model resulted in a significant increase in the amount of variance in depression explained, ΔR2 = .15, F(1, 268) = 54.72, p < .001, with the full model accounting for 26% of the variance in depression, adjusted R2 = .26, F(4, 268) = 24.35, p < .001. Once trauma appraisals were added to the model, the independent effects of the MBTs and HBTs no longer reached statistical significance.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression Analysis Predicting Depression, Dissociation, and PTSD Symptoms within and by Level of Betrayal and Appraisals (N = 273)

| Step 1 | Step 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Depression | ||||||

| LBT | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.05 |

| MBT | 0.64 | 0.28 | 0.15* | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.03 |

| HBT | 1.11 | 0.31 | 0.23*** | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.06 |

| Appraisals | 2.67 | 0.36 | 0.46*** | |||

| Dissociation | ||||||

| LBT | 0.48 | 0.24 | 0.12* | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.11* |

| MBT | 0.47 | 0.21 | 0.15* | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.03 |

| HBTs | 0.76 | 0.23 | 0.21*** | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.04 |

| Appraisals | 1.97 | 0.28 | 0.45*** | |||

| PTSD | ||||||

| LBT | 2.38 | 0.99 | 0.13* | 2.28 | 0.77 | 0.12** |

| MBT | 2.17 | 0.86 | 0.15* | −0.23 | 0.60 | −0.02 |

| HBT | 6.82 | 0.95 | 0.41*** | 2.85 | 0.79 | 0.17*** |

| Appraisals | 12.84 | 0.95 | 0.64*** | |||

Note. LBT is low betrayal trauma; MBT is moderate betrayal trauma; HBT is high betrayal trauma.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Dissociation

As with depression, the cumulative trauma indices accounted for a significant amount of the variance in dissociation, adjusted R2 = .11, F(3, 269) = 12.30, p < .001. Level of dissociation increased significantly as the number of LBTs, MBTs, and HBTs increased (Table 2), and as predicted, HBTs contributed the most to the model, followed by MBTs and LBTs (lmgs = 0.06, 0.04, and 0.02, respectively). The amount of explained variance in dissociation increased significantly after trauma appraisals were added to the model, ΔR2 = .14, F(1, 268) = 51.03, p < .001, with the full model accounting for 25% of the variance in dissociation, adjusted R2 = .25, F(4, 268) = 23.70, p < .001. LBTs, but not MBTs or HBTs, remained a significant predictor of dissociation after trauma appraisals were added to the model.

PTSD

Similar to the other trauma-related symptoms, the cumulative trauma indices accounted for a significant amount of the variance in PTSD symptoms, adjusted R2 = .28, F(3, 269) = 35.66, p < .001. Cumulative trauma at each level of betrayal—LBTs, MBTs, and HBTs—significantly predicted symptoms of PTSD (Table 2), and as hypothesized, HBTs contributed the most to the model, followed by MBTs and LBTs (lmgs = 0.19, 0.07, and 0.03, respectively). When the trauma appraisals were added to the model, the amount of explained variance in PTSD increased significantly, ΔR2 = .29, F(1, 268) = 182.09, p < .001, with the full model accounting for 57% of the variance in PTSD, adjusted R2 = .57, F(4, 268) = 90.24, p < .001. LBTs and HBTs remained significant predictors of PTSD symptoms after trauma appraisals were added to the model.

Predicting Trauma Appraisals

A hierarchical linear regression was conducted to test hypothesis 4, that increases in cumulative trauma, would be associated with stronger appraisals, where HBTs would be the most predictive, followed by MBTs and LBTs, respectively. To assess the relative importance of the cumulative trauma indices, lmgs were examined at the final step. Multicollinearity problems were assessed (Pedhazur, 1997), but were not problematic. Gender was controlled for due to its significant association to trauma appraisals (Table 1) and was entered in the first step of the model. The three cumulative trauma indices were then entered sequentially, by level of betrayal (low to high), for a total of four steps. In Step 1, gender accounted for a significant portion of the variance in trauma appraisals, adjusted R2 = .02, F(1, 271) = 4.78, p = .030, with women making significantly stronger appraisals (Table 3). The addition of LBTs in Step 2 of the model, contrary to our hypothesis, did not result in a significant increase in the amount of variance in appraisal strength explained, ΔR2 = .01, F(1, 270) = 3.20, p = .075. Gender remained a significant predictor when LBTs were entered into the model.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis Predicting Appraisal Strength within and by Level of Betrayal Severity (N = 273)

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Gender | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.13* | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.13* | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.12* | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| LBT | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | |||

| MBT | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.43*** | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.26*** | ||||||

| HBT | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.36*** | |||||||||

Note. Reference category for gender is female. LBT is low betrayal trauma; MBT is moderate betrayal trauma; HBT is high betrayal trauma.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

The amount of explained variance in the strength of trauma appraisals increased significantly after MBTs were added to the model in Step 3, ΔR2 = .17, F(1, 269) = 56.91, p < .001. MBTs significantly predicted appraisal strength, and gender remained a significant predictor. In the final step of the model, the inclusion of HBTs also resulted in a significant increase in the amount of variance in trauma appraisal strength explained, ΔR2 = .10, F(1, 268) = 39.64, p < .001. The full model explained 29% of the variance in appraisal strength, adjusted R2 = .29, F(4, 268) = 28.95, p < .001. Increases in MBTs and HBTs were associated with significant increases in trauma appraisal strength, with HBTs making the largest contribution, followed by MBTs and LBTs (lmgs = 0.18, 0.12, and < 0.01, respectively). Finally, when HBTs were included in the model, gender failed to reach statistical significance.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the role of cumulative trauma categorized by level of betrayal, gender, and the role of trauma appraisals on depression, dissociation, and PTSD symptoms. Consistent with prior research (Arata et al., 2005; Edwards et al., 2003; Finkelhor et al., 2007a; 2007b; Greif Green et al., 2010), these results suggest that trauma survivors are likely to experience more than one trauma type, highlighting that, for many, trauma exposure is more akin to an on-going risk rather than an isolated event (Finkelhor, 2007a).

Men and women differed in their exposure to HBTs, with women experiencing more. In contrast, men and women were equally likely to have experienced LBTs and MBTs. These results correspond with other studies that have compared interpersonal to noninterpersonal trauma and further the relational closeness of the survivor and perpetrator (Goldberg & Freyd, 2006; Kaehler & Freyd, 2009; Tang & Freyd, in press). Although women endorsed more traumas perpetrated by someone close to them, they did not endorse more depression, dissociation, or PTSD symptoms than men. The relatively equal levels of trauma symptomatology across gender might have resulted from sampling a college student population. However, similar studies with college students have found gender differences in PTSD symptoms (Cromer & Smyth, 2010). Alternatively, it might be that the gender differences frequently found in trauma-related symptomatology are mediated by the survivor-perpetrator relationship (Tang & Freyd, in press), and there was not enough variability in the number of unique HBTs experienced (ranging from 0 to 3) across gender compared to studies that have considered differences in the overall frequency of each HBT event (Tang & Freyd, in press).

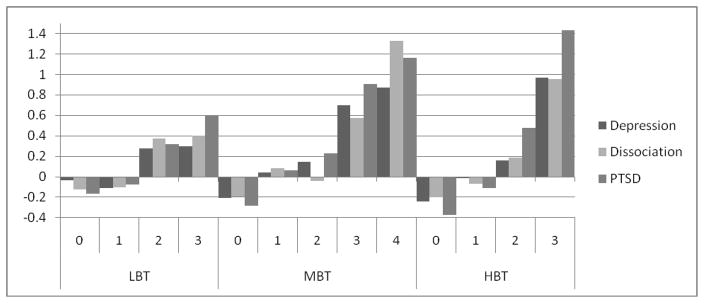

Trauma symptomatology was predicted both by the cumulative experiences of trauma types within and by the level of betrayal. As hypothesized, trauma-related symptoms increased as the number of different trauma types increased within the LBT (with the exception of depression), MBT, and HBT categories, which is consistent with similar studies (e.g., Finkelhor, 2007a; 2007b). Moreover, we found that HBTs contributed more to models predicting trauma symptomatology, followed by MBTs, and LBTs (Figure 1). These findings suggest that in addition to the number of different trauma types experienced, the level of betrayal might contribute to our understanding of the development of trauma symptoms. In particular, these results demonstrate that even among interpersonal traumas, those perpetrated by someone with whom the victim shares a close relationship are associated with more symptoms than those perpetrated by someone with whom the victim is not close. Survivors of HBTs might experience more trauma symptoms for several reasons. HBT survivors may be prone to make negative self-appraisals in order to maintain a relationship with an abusive attachment figure. Furthermore, HBT survivors have been shown to experience more adverse events during childhood (Edwards et al., accepted pending minor revisions) and higher revictimization rates than do survivors of other trauma types (Gobin & Freyd, 2009). Also, the multilateral nature of HBTs, in which two developmental systems—attachment and individuation—are affected might be influential in HBT survivors experiencing more distress (Kira, Lewandowski, Templin, Ramaswamy, Ozkan, & Mohanesh, 2008). Importantly, this distinction in the level of trust within interpersonal traumas is not always identified in the literature, yet appears to be a critical factor when examining the harmful effects of trauma.

Figure 1. Trauma symptom z-scores within and by the level of betrayal.

Note. LBT is low betrayal trauma; MBT is moderate betrayal trauma; HBT is high betrayal trauma; PTSD is posttraumatic stress disorder.

When trauma appraisals were considered, they predicted depression, dissociation, and PTSD symptoms over and above the cumulative trauma indices. Moreover, the prior significant associations between cumulative trauma and depression and dissociation, no longer reached statistical significance (with the exception of LBTs and dissociation) when trauma appraisals were considered. This finding suggests that it is the manner in which trauma survivors evaluate the trauma experiences rather than cumulative trauma exposure or level of betrayal that most meaningfully predicts depression and dissociation. On the other hand, for PTSD symptoms, LBTs and HBTs were significant predictors in addition to trauma appraisals. One possible explanation for the differences in trauma indices predicting symptomatology after appraisals have been considered might be that PTSD symptoms may be directly linked to the traumas experienced, whereas symptoms of depression and dissociation may be more associated with the way traumas are interpreted or appraised. Moreover, the majority of items on the questionnaire utilized to assess PTSD focused on symptoms specifically related to a traumatic event.

Cumulative trauma by level of betrayal was also associated with the strength of trauma appraisals. Although LBTs did not significantly contribute to appraisal strength, both MBTs and HBTs did. Further, women made stronger negative appraisals compared with men, but when HBTs were considered, this gender difference became negligible, indicating that survivors of HBTs make more negative appraisals across gender. Thus, in terms of survivors’ assessments of their beliefs, behaviors, and emotions regarding trauma exposure, not all traumas are equal: interpersonal traumas, especially those where trust is violated, are associated with stronger negative appraisals. These findings have important implications for treatment applications. In particular, beyond the amount of trauma experienced, the way in which trauma survivors assess their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in response to trauma exposure is directly related to trauma-relevant symptomatology. Thus, a better understanding of how survivors, particularly those having experienced interpersonal traumas by someone they trust, assess their experiences is important for cognitively-based treatment.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study contributes to our understanding of the differential effects of cumulative trauma on trauma-related symptomatology when the level of betrayal and cognitions about the traumas are considered. There are some limitations however. First, the study used a convenience sample comprised of college students. Although college students are a heterogeneous group, with diverse backgrounds and trauma experiences occurring before and during their university tenure, a replication of these results in a larger community sample or a highly traumatized sample would be beneficial. Participants were predominantly female and Caucasian, and so generalization is limited. Although we were interested in examining potential gender differences, our sample was primarily female, and a lack of power may have limited our results. Additional limitations include not counting multiple perpetrators separately, and the cross-sectional and retrospective-self-report nature of the study. However, some researchers (e.g., Arata et al., 2005) have argued that conducting retrospective studies with college students may be more advantageous in reducing errors associated with retrospective reporting, as the amount of time between reporting and the actual experience of trauma may be reduced. Alternatively, the study’s reliance on self-report measures might have resulted in an underreporting of traumatic life experiences (Tang, Freyd, & Wang, 2007).

Future research would benefit from longitudinal designs and varied methods for assessing trauma exposure. In addition to examining community and highly traumatized samples, the types of traumas included in the cumulative index should be expanded to include other forms of adversity and trauma that have been assessed in other studies. For example, in addition to child emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study included forms of household dysfunction such as substance abuse, mental illness, or the incarceration of a household member, as well as parental separation or divorce (e.g., Anda et al., 2006). Kira and colleagues (Kira, Lewandowski, Templin, Ramaswamy, & Mohanesh, 2010; Kira, Smith, Lewandowski, & Templin, 2010) have found that intergroup traumas, such as discrimination (i.e., race, gender, sexual orientation, and religion), are also a strong independent predictor of trauma-related symptomatology and cumulative trauma research might benefit from the inclusion of these adversities. Finally, future research might also benefit from a more focused examination of trauma appraisals, including appraisal category and the cumulative effect of appraisals. Recent studies suggest that specific categories of appraisals (e.g., threat, alienation) might differentially relate to trauma-related symptomatology (DePrince, Chu, & Pineda, in press) and that cumulative negative appraisals might be a stronger predictor than cumulative trauma (Kira et al., 2011).

Conclusions

Although trauma exposure is relatively common, determining who is at greatest risk for developing persistent trauma symptomatology is quite complex. Given the long-lasting nature of trauma-related symptoms for some trauma survivors, continued research in this area is needed to better inform intervention and treatment efforts. The results from this study suggest that the level of betrayal and trauma appraisals are both important factors that should be considered. More specifically, HBTs were associated with more depression, dissociation, and PTSD symptoms than MBTs and LBTs. However, when trauma appraisals were considered, appraisals were stronger predictors of outcomes than the cumulative trauma indices, suggesting that the manner in which trauma survivors think about and evaluate their experiences is an important component in determining prolonged distress, regardless of the trauma experienced. The strength of survivor’s appraisals was influenced by the level of betrayal they experienced, with appraisal strength increasing as MBTs and HBTs increased. Although women were more likely to experience HBTs than men, they were no more likely to experience symptoms of depression, dissociation, or PTSD than men. These findings highlight the importance of considering not only the quantity of unique traumas experienced and the quality of the trauma survivors’ relationship to the perpetrator, but the appraisals of trauma made, to better understand the long-term impact of trauma.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by NIMH grant MH06824-01A1 awarded to the third author; and the University of Oregon Foundation Fund for Research on Trauma and Oppression. We would like to thank all of the participants and our colleagues from the Dynamics Lab and the Traumatic Stress Studies Group.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/TRA

Contributor Information

Christina Gamache Martin, University of Oregon.

Lisa DeMarni Cromer, University of Tulsa.

Anne P. DePrince, University of Denver

Jennifer J. Freyd, University of Oregon

References

- Accortt EE, Freeman MP, Allen JJB. Women and major depressive disorder: Clinical perspectives on causal pathways. Journal of Women’s Health. 2008;17:1583–1590. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner DJ, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Giles WH. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;256:174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews B, Brewin CR, Rose S, Kirk M. Predicting PTSD symptoms in victims of violent crime: The role of shame, anger, and childhood abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:69–73. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arata CM, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Bowers D, O’Farrill-Swails L. Single versus multi-type maltreatment: An examination of the long-term effects of child abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2005;11:29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow MR, Cromer LD. Trauma-relevant characteristics in a university human subjects pool population: Gender, major, betrayal and latency of participation. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation. 2006;7:59–75. doi: 10.1300/J229v07n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N. The epidemiology of trauma, PTSD, and other posttrauma disorders. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2009;10:198–210. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Psychometric review of the Trauma Symptom Checklist-40. In: Stamm BH, editor. Measurement of stress, trauma, and adaptation. Lutherville, MD: Sidran Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Jordan CE. Childhood maltreatment, intervening variables, and adult psychological difficulties in women: An overview. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2009;10:375–388. doi: 10.1177/1524838009339757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Runtz M. The Trauma Symptom Checklist (TSC-33): Early data on a new scale. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1989;4:151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Cromer LD, Smyth JM. Making meaning of trauma: Trauma exposure doesn’t tell the whole story. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2010;40:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- DePrince AP. Social cognition and revictimization risk. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation. 2005;6:125–141. doi: 10.1300/J229v06n01_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePrince AP, Chu AT, Pineda AS. Links between specific posttrauma appraisals and three forms of trauma-related distress. Psychological Truama: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy (in press) [Google Scholar]

- DePrince AP, Freyd JJ. Memory and dissociative tendencies: The roles of attentional context and word meaning in a directed forgetting task. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2001;2:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- DePrince AP, Zurbriggen EL, Chu AT, Smart L. Development of the Trauma Appraisal Questionnaire. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma. 2010;19:275–299. [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DR, Thompson TJ, …Giles WH. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Freyd JJ, Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ. Health outcomes by closeness of sexual abuse perpetrator: A test of Betrayal Trauma Theory. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma (accepted pending minor revision) [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, Anda RF. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: Results from the adverse childhood experiences study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1453–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:319–345. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis AA, Nixon RDV, Williamson P. The effects of social support and negative appraisals on acute stress symptoms and depression in children and adolescents. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;48:347–361. doi: 10.1348/014466508X401894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother N, Rachman S. PTSD in victims of sexual assault: Test of a major component of the Ehlers-Clark theory. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2006;37:74–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007a;31:7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Development and Psychopathology. 2007b;19:149–166. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth D. R package version 0.9–6. 2006. relimp: Relative Contribution of Effects in a Regression Model. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Steketee G, Rothbaum BO. Behavioral/cognitive conceptualizations of post-traumatic stress disorder. Behavior Therapy. 1989;20:155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Freyd JJ. Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Freyd JJ, Klest B, Allard CB. Betrayal trauma: Relationship to physical health, psychological distress, and a written disclosure intervention. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2005;6:83–104. doi: 10.1300/J229v06n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavranidou M, Rosner R. The weaker sex? Gender and post-traumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2003;17:130–139. doi: 10.1002/da.10103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie CF, Bradley B, Mercer K, Smith AK, Conneely K, Gapen M, Ressler KJ. Trauma exposure and stress-related disorders in inner city primary care patients. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31:505–514. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobin RL, Freyd JJ. Betrayal and revictimization: Preliminary findings. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2009;1:242–257. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR, Freyd JJ. Self-reports of potentially traumatic experiences in an adult community sample: Gender differences and test-retest stabilities of the items in a Brief Betrayal Trauma Survey. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2006;7(3):39–63. doi: 10.1300/J229v07n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greif Green J, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication I: Associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grömping U. Relative importance for linear regression in R: The package relaimpo. Journal of Statistical Software. 2006;17:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kaehler LA, Freyd JJ. Boderline personality characteristics: A betrayal trauma approach. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2009;1:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1993;29:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90026-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kira IA, Lewandowski L, Templin T, Ramaswamy V, Ozkan B, Mohanesch J. Measuring cumulative trauma dose, types, and profiles using a development-based taxonomy of traumas. Traumatology. 2008;14:62–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kira IA, Lewandowski L, Templin T, Ramaswamy V, Ozkan B, Mohanesch J. The effects of perceived discrimination and backlash on Iraqi refugees’ mental and physical health. Journal of Muslim Mental Health. 2010;5:59–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kira IA, Smith I, Lewandowski L, Templin T. The effects of gender discrimination on refugee torture survivors: A cross-cultural traumatology perspective. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2010;16:299–306. doi: 10.1177/1078390310384401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kira IA, Templin T, Lewandowski L, Ramaswamy V, Ozkan B, Abou-Mediane S, Alamia H. Cumulative tertiary appraisals of traumatic events across cultures: Two studies. Journal of Loss & Trauma. 2011;16:43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer SR, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE. Mental health correlates of the victim-perpetrator relationship among interpersonally victimized adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1333–1353. doi: 10.1177/0886260506291654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman RH, Merenda PF, Gold RZ. Introduction to Bivariate and Multivariate Analysis. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Norris HF, Perilla JL. The Revised Civilian Mississippi Scale for PTSD: Reliability, validity, and cross-language stability. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:285–298. doi: 10.1007/BF02110661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedhazur EJ. Multiple regression in behavioral research: Explanation and prediction. 3. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Nelson Thompson Learning; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2006. URL http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BE. Understanding children exposed to violence: Toward an integration of overlapping fields. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:356–376. [Google Scholar]

- Tang SSS, Freyd JJ. Betrayal trauma and gender differences in posttraumatic stress. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Tang SS, Freyd JJ, Wang M. What do we know about gender in the disclosure of child sexual abuse? Journal of Psychological Trauma. 2007;6(4):1–26. [Google Scholar]