Abstract

Despite the growing recognition for multidimensional assessments of cue-elicited craving, few studies have attempted to measure multiple response domains associated with craving. The present study evaluated the Ambivalence Model of Craving (Breiner et al., 1999; Stritzke et al., 2007) using a unique cue reactivity methodology designed to capture both the desire to use (approach inclination) and desire to not consume (avoidance inclination) in a clinical sample of incarcerated female substance abusers. Participants were 155 incarcerated women who were participating in or waiting to begin participation in a nine-month drug treatment program. Results indicated that all four substance cue-types (alcohol, cigarette, marijuana, and crack cocaine) had good reliability and showed high specificity. Also, the validity of measuring approach and avoidance as separate dimensions was supported, as demonstrated by meaningful clinical distinctions between groups evincing different reactivity patterns and incremental prediction of avoidance inclinations on measures of stages of change readiness. Taken together, results continue to highlight the importance of measuring both approach and avoidance inclinations in the study of cue-elicited craving.

Keywords: approach, avoidance, craving, cue reactivity, incarcerated females

Ambivalence about substance use, defined as the simultaneous desire to use and to not use psychoactive substances, has been identified as a hallmark feature of addiction, and is central to many clinical formulations of substance use disorders (e.g., Orford, 2001; Heather, 1998). Nevertheless, ambivalence is often overlooked in the study of substance cue reactivity, or how individuals respond to cues as a function of their association with psychoactive substance use. The present study sought to address this oversight by examining a unique cue reactivity methodology (Stritzke, Breiner, Curtin, & Lang, 2004; Curtin, Barnett, Colby, Rohsenow, and Monti, 2005) in a clinical sample of substance abusers. Specifically, we aimed to provide further validation to the Ambivalence Model of Craving using both a pictorial cue reactivity methodology developed by Stritzke and colleagues (2004) and a clinical sample of incarcerated female substance abusers.

Approach and Avoidance Inclinations: Primary Dimensions of Cue Reactivity

Theories attempting to account for substance users’ responses to drug cues typically focus on “craving”, which has been defined as cue-elicited motivation to consume the substance (e.g., Baker, Morse, & Sherman, 1987; Stewart, de Wit, & Eikelboom, 1984; Tiffany, 1990). Cue-elicited craving is thought to develop through a process of conditioning, in which drug-related cues are repeatedly paired with positively and/or negatively reinforcing drug effects (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004; Stewart et al., 1984; Niaura, Rohsenow, Binkoff, & Monti, 1988). Unfortunately, conceptualizations based solely on the reinforcing effects of drugs lack the capacity to account for the ambivalence that substance abusers commonly display toward the drugs they abuse. Over the past decade there has been a shift in perspective such that reactivity to drug cues is no longer viewed as a unidimensional process, but rather a complex, multidimensional process consisting of a rather broad constellation of psychological and physiological response domains that vary independently of one another, and are reflective of competing neurobiological systems associated with motivations to approach or avoid using substances (Stritzke, McEvoy, Wheat, Dyer, & French, 2007; Breiner, Stritzke, & Lang, 1999; Sayette, Shiffman, Tiffany, Niaura, Martin, & Shadel, 2000; Carter & Tiffany, 1999).

To better capture the range of craving experiences, Breiner et al (1999) introduced an ambivalence conceptualization of craving that called for independent assessment of both approach and avoidance inclinations to use psychoactive substances. More precisely, craving is defined using a multidimensional framework that represents the “relative activation of substance-related response inclinations along the primary dimensions of approach and avoidance (Stritzke et al., 2007).” Approach reactivity is defined as an inclination to approach and consume the substance, and is presumed to develop as a function of the reinforcing effects of psychoactive substance use, including pleasurable drug effects and relief of negative states (Breiner et al., 1999). In contrast, avoidance reactivity is defined as an inclination to withdraw and refrain from consuming the substance, which develops as a function of the negative consequences that follow the excessive use of psychoactive substances (Breiner et al., 1999). These two dimensions of reactivity, or craving, are thought to develop through different psychobiological systems following repeated, systematic exposure to reinforcing and punishing events associated with such substance use (Ledoux, 2000; Lang, 1995; Stasiewicz & Maisto, 1993), and are proposed to be orthogonal to one another resulting in four hypothetical quadrants (predominantly approach, predominantly avoidant, ambivalence, and indifference) (Breiner et al., 1999; McEvoy, Stritzke, French, Lang, & Ketterman, 2004). Measurement of inclinations to approach and to avoid substance use as separate dimensions has numerous advantages clinically and methodologically (see Stritzke et al., 2007 for a review). More important, it has been argued that measuring “craving” or “urge to use” exclusively in terms of approach inclination without consideration of a separate, yet concurrent, avoidance inclination may misrepresent a motivational disposition that is actually a combination of both approach and avoidant motivation, thus significantly diminishing the utility of the information obtained (Breiner et al., 1999).

Despite advances in the conceptualization of craving and the importance of measuring both approach and avoidance inclinations concurrently on cue reactivity tasks, there is limited research standardizing the measurement of such dimensions. To address this issue, Stritzke and colleagues (2004) developed a methodology using pictorial cues (i.e. alcohol cues, cigarette cues, non-alcoholic cues, and food items) that allowed for the study of both approach and avoidance inclinations. In their initial study, non-substance abusing participants viewed pictorial cues and were asked to report their approach and avoidance inclinations as well as their level of general arousal. Results from both arousal-control and cross-over response designs (Robbins & Ehrman, 1992; see Stritzke et al., 2004 for details) indicated that participants’ approach and avoidance ratings varied systematically based on their experiences with the substances depicted in the visual cue presentations. Moreover, this effect was not due to between-group differences in general arousability. The findings also supported the utility of measuring avoidance inclination separately from approach inclination, by demonstrating that subgroups separated into clinically significant categories with similar levels of approach inclination, but were differentiated by their level of avoidance inclination (e.g., smokers trying to quit smoking showed high approach and high avoidance to cigarette cues, i.e. ambivalence, while smokers not trying to quit smoking showed high approach and low avoidance, i.e. predominantly approach; see Stritzke, et., al., 2004). Finally, results indicated that the avoidance dimension captured additional variance beyond the approach dimension on several substance related variables.

Overall, findings from this study demonstrated the validity of measuring both approach and avoidance dimensions of craving independently, and demonstrated that these dimensions of reactivity may provide important information in the etiology and maintenance of substance use disorders as well as readiness for change. Although these procedures have been replicated in an adolescent sample (Curtin et al., 2005), a major limitation has been the lack of research in clinical samples. Thus, the current study sought to further validate the assessment of both approach and avoidance inclinations using a pictorial cue-reactivity paradigm and clinical sample.

Characteristics of Incarcerated Women in Treatment for Substance Abuse

In developing this study, we chose incarcerated women as our target population for several reasons. First, previous studies examining the characteristics of incarcerated women indicate high rates of severe and chronic substance abuse that is often complicated by a host of pre- and co-morbid psychological and social problems (Langan & Pelissier, 2001; Peters, Strozier, Murrin, & Kearns, 1997; Williams, 2001; McClellan, Farabee, & Crouch, 1997; Pelissier, Camp, Gaes, Saylor, & Rhodes, 2003). Based on this information, we speculated that the substance abusers in this population would have experienced a significant history of reinforcement and punishment as a result of their drug use, and therefore should have developed substantial approach and avoidance reactivity to drug cues. Arguably, by the time the circumstances of their lives deteriorated to the point of incarceration, these substance-abusing women were likely to have developed intense ambivalence regarding their substance use. Indeed, a major aim of the current study was to examine the validity of independently measuring both the approach and the avoidance reactivity components of this ambivalence.

Second, there are no studies of substance cue reactivity in incarcerated substance abusers and studying cue reactivity in a prison setting offered a unique opportunity to examine reactivity to substance use cues outside of a laboratory setting. Thus, a secondary aim of the present study was to determine whether our particular substance cue reactivity methodology would function effectively in this unique context, eliciting reliable approach, avoidance, and arousal reactivity patterns that are meaningfully linked to participants’ substance use histories and related individual differences.

The Current Study

The current study was designed to examine the reliability and validity of assessing both approach and avoidance inclinations during a cue-exposure paradigm within a clinical sample of substance users. Specifically, we presented photographic cues depicting cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, marijuana, crack cocaine, food, and non-alcoholic beverages to female prison inmates with diagnosed substance use disorders. Participants reported their momentary arousal, approach, and avoidance reactions to each image. They then responded to a series of self-report instruments that assessed current and historical aspects of substance use. The following hypotheses were tested:

-

Hypothesis 1

We predicted significant History of Substance Use (no use, non-problematic use, problematic use; or cigarettes per day) X Cue Content (alcohol, cigarette, marijuana, crack cocaine, control) interactions such that arousal ratings for cues would vary between groups differing in self-reported levels of use of that substance, and no differences between these groups for other drug and control cues. Specifically, we expected to find a linear increase in arousal ratings as severity (or frequency for cigarettes) of use increases.

-

Hypothesis 2

We predicted significant History of Substance Use X Cue Content interactions such that approach and avoidance ratings for cues would vary between groups differing in self-reported levels of past use of that substance, but there would be no differences between these groups in ratings of cues for other drugs or control cues. Specifically, we expected to find a linear increase in approach ratings as severity (or frequency for cigarettes) of use increases. In contrast, we expected a linear decrease in avoidance inclinations as severity (or frequency of cigarette) of use increases.

-

Hypothesis 3

Avoidance ratings of substance cues would demonstrate incremental validity such that, after controlling for variance explained by approach ratings, avoidance ratings would predict unique variance in measures of stages of change readiness and treatment eagerness. Specifically, we expected to find unique positive relationships between avoidance ratings and taking steps to make a change.

Method

Participants

Participants were 155 women incarcerated in the Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) located in Tallahassee, Florida. All participants were recruited from the prison’s Residential Drug Abuse Program (RDAP) or the RDAP waitlist. Their age ranged from 21 to 64 years old, with a mean age of 35.11 (SD=9.36) years old at time of participation. Sixty percent (n=93) were Caucasian, 35.5% (n=55) African American, and 4.5% unknown due to missing data. Approximately 66% (n=102) had completed high school or obtained a GED, with another 13.5% (n=21) enrolled in GED preparation classes, 9% (n=14) enrolled in pre-GED preparation classes, and 3.9% (n=6) enrolled in GED classes for persons with special learning needs (n=12 unknown educational status). Sixty-six percent (n=102) were incarcerated on drug possession or trafficking convictions (of which n=49 related to cocaine, n=29 related to methamphetamine, and n=11 related to marijuana), whereas 34% (n=53) were incarcerated for crimes other than drug offenses (e.g., fraud, robbery, money laundering, racketeering). The sentence lengths for participants ranged from 18 to 324 months, with a mean of 49.1 months (SD=31.94).

All participants were determined to be eligible for admission into the prison’s nine-month RDAP, which was based upon diagnosis of one or more substance use disorders obtained from a structured clinical interview conducted by one of the prison’s Drug Treatment Specialists. In addition, those eligible had to demonstrate sufficient cognitive ability to effectively manage the material presented throughout the 9-month cognitive-behavioral program. Over a 10-month span, 117 participants were recruited from RDAP groups in progress (time in treatment ranged from 1–8 months), while the remaining 38 were recruited from the RDAP waiting list.

Materials

Equipment

A Dell laptop computer and a projection unit were used to project the substance cues and instruction slides onto a blank Dry-Erase board. Microsoft PowerPoint® software was used to control the timing and presentation of the preparatory slides, substance cues, and rating periods.

Slides

Fifty-four substance cue slides were presented to represent six appetitive substance categories: alcoholic beverages (n = 12; 6 beer, 3 wine, and 3 hard liquor), cigarettes (n = 6), marijuana (n = 6), crack cocaine (n = 6), food (n = 12; 6 “healthy”, e.g., vegetables and fruit, and 6 “unhealthy”, e.g., high fat, high calorie, high refined sugar foods), and non-alcoholic beverages (n = 12; 6 non-caffeinated and 6 caffeinated). Within all categories, individual cues varied by setting (e.g., bar, restaurant, home, neutral background) and activity state (e.g., substance sitting untouched on table, held in hand, or actively consumed). Brand names and identifying symbols were excluded to the extent possible. The alcoholic beverage, cigarette, food, and non-alcoholic beverage images were obtained from the Normative Appetitive Picture System (NAPS; Stritzke et al., 2004). The crack-cocaine images were obtained from a previous study with permission from the author (Coffey et al., 1998), and the marijuana images were created specifically for the current study by members of our laboratory responsible for the NAPS. Following similar procedures outlined by Stritzke et al., 2004 on the creation of the NAPS, marijuana cues were photographed depicting different paraphernalia (e.g., papers, joints, pipes) and activity states (e.g., lighting a joint or pipe, toking). Images were then selected based on positive ratings by experienced users on initial content validity.

To eliminate potential order effects, the six cue types were distributed evenly across three sets of 18 images, and these three image sets were combined to create six different presentation orders. Each of the six orders was presented to a subset of the participants. Within each set of 18 images, cues were arranged in a quasi-random order such that there were never two of any cue type in a row, and a particular cue type was not systematically followed by the same other cue type (e.g., alcohol cues were not always followed by cigarette cues).

Measures

Substance Cue Reactivity Ratings

“Approach,” “Avoidance,” and “Arousal” ratings were obtained for each substance cue image presentation. Approach was defined as wanting to consume the depicted item. Avoidance was defined as wanting to avoid consuming the depicted item. Each of these two dimensions was rated on a 9-point scale (0=not at all to 8=very much). Participants were told that the scales should be regarded as independent of one another (Powell et al., 1993), and examples of possible response patterns across the two scales were given as part of the instructions for the rating task. The arousal item was intended to assess the participants’ feelings of calmness versus arousal in reacting to the images. A 9-point scale, with “completely calm” (0) and “completely aroused” (8) as the anchor points and “neutral” (4) as the midpoint, was used for these ratings (Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1999). A separate ratings page was provided for each cue, and the order of presentation of rating scales for Approach, Avoidance, and Arousal was counterbalanced across cues.

A fourth item was added to the end of each rating page asking participants to best describe the item (non-alcoholic beverage, alcoholic beverage, cigarettes, marijuana, cocaine, healthy food, unhealthy food, and other). Participants were instructed to write in their response if they chose the “other” category and to give their best guess if they weren’t sure. This question was administered to examine the content validity of the cues.

Substance Use History

Information about participants’ drug use prior to incarceration was obtained from a diagnostic interview used to determine eligibility for the RDAP. Using this information, participants were classified for each substance as (see Table 1): 1) No or Minimal recent use (includes no or minimal lifetime use and, last use more than three years prior to incarceration); 2) Non-Problem Use prior to incarceration; 3) Problem Use prior to incarceration (includes abuse and dependence). For cigarette use, participants were categorized as Non-smokers, light smokers (5 or fewer cigarettes per day), moderate smokers (10 cigarettes per day), or heavy smokers (20 or more cigarettes per day)

Table 1.

Exploration of Reactivity Space by History of Use

| Indifferent | Avoidant | Approach | Ambivalent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarettes | ||||

| 0 cigs/day (n=30) | 5 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 cigs/day (n=24) | 4 | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| 10 cigs/day (n=39) | 5 | 2 | 22 | 10 |

| 20 cigs/day (n=32 | 1 | 0 | 28 | 3 |

| Alcohol | ||||

| No/Minimal (n=6) | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-Problematic (n=58) | 8 | 38 | 8 | 4 |

| Problematic (n=89) | 12 | 37 | 18 | 22 |

| Marijuana | ||||

| No/Minimal (n=35) | 1 | 32 | 0 | 2 |

| Non-Problematic (n=45) | 1 | 32 | 2 | 8 |

| Problematic (n=73) | 5 | 20 | 24 | 21 |

| Crack-Cocaine | ||||

| No/Minimal (n=88) | 13 | 72 | 0 | 2 |

| Non-Problematic (n=21) | 0 | 17 | 2 | 2 |

| Problematic (n=43) | 7 | 25 | 2 | 8 |

Note: Sum of the reactivity dimensions may not equal the total based on history of use classification due to an inability to classify average scores of 4 on approach and/or avoidance.

Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES; Miller & Tonigan, 1996)

The Socrates is a 19-item self-report measure developed to evaluate readiness to change among drinkers or drug users and forms three subscales: recognition of problematic use, ambivalence regarding problematic use and changing, and taking steps to change use. Participants respond to each item using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The SOCRATES has demonstrated good psychometric properties, including internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Miller & Tonigan, 1996).

Procedure

During recruitment, prospective participants were told the purpose of the study was to examine people’s responses to pictures associated with common habits, such as drinking, smoking, eating, and drug using. They were told participation was voluntary, and that the study would require them to complete two tasks over three sessions: a) an image rating task, in which they would view and rate pictures of commonly consumed items such as food, beverages, and drugs, and b) a self-report task, in which they would complete a series of questionnaires relating to their behavior and attitudes. Potential recruits were informed they would be given one Krispy Kreme Original Glazed® doughnut at each session, as a token of appreciation for their participation.

A maximum of 15 participants attended each experimental session (approximately 2.5 hours in length and one week apart), which were held in one of four group therapy rooms located in the prison’s RDAP unit. Treatment group cohorts participated in the experimental sessions as a group, during regularly scheduled meeting times. Treatment group-members who chose not to participate in the study were given an alternate assignment to complete in a different location. Study participants who were recruited from the RDAP waiting list attended scheduled experimental sessions in one of the RDAP group therapy rooms.

Session 1 always began with the cue reactivity task, which took approximately 1.25 hours to complete. Prior to the start of each task, participants were reminded that their responses would be kept confidential and that there were no right or wrong answers. Next, materials needed to complete the image-rating task (three ratings packets, numbered 1 to 18, 19 to 36, and 37 to 54, and a pencil) were distributed. After distributing these materials, the experimenter read the standardized instructions describing the cue presentation and rating procedure and provided an opportunity for participants to ask questions about the task. Participants were further instructed to refrain from commenting about the images and/or their ratings during the procedure to avoid the possibility of biasing others’ ratings. Participants viewed and rated all 54 images as presented in one of the six pre-determined orders described above. Each image rating trial began with a 5 s presentation of a preparatory slide that served to focus participants’ attention on the screen. Each preparatory slide was followed by a substance cue image, which was presented for 6 s, and was followed by a 45 s rating/relaxation period. Based on findings from pilot studies of the present protocol and previous studies using a similar procedure, it was expected that participants would generally finish their ratings within 30 s, leaving a relaxation period of about 15 s before the next preparatory slide signaled the next substance cue.

Following the cue reactivity task, participants were given a 15-minute break. Break times coincided with a period of permitted inmate movement on the prison compound, so that participants were able to go outside to smoke in the designated smoking area if they chose to do so. Before participants started filling out the questionnaires, the experimenter read instructions for the task aloud to the participants, emphasizing the need to pay attention to the differing time frames among the questionnaires (e.g., “past 30 days”, “past year prior to the start of the present incarceration”). Participants were reminded to read the instructions for each questionnaire carefully before they began responding to the items. During Session 2, participants continued to fill out questionnaires started during session 1 and were given similar 15-minute breaks. The final session (session 3) was held for participants to finish any remaining questionnaires.

Results

Content Validity and Reliability of Reactivity Ratings by Substance Cue Category

To examine the content validity of the pictorial cues, percentages were calculated for correct identification of the substance in the image. A cue was considered to have poor content validity if it was correctly identified by less than 85% of all participants. Using this cutoff, one cigarette cue (female lighting cigarette, 78.4%), one marijuana cue (pot pipe and smoke, 82.5%) and two crack cocaine cues (crack rock in can pipe, 82.6%; crack rock, 80%) were dropped from the cue sets and subsequent analyses. Cronbach’s alphas for approach and avoidant ratings for the four drug categories ranged from .85 to .97 indicating good reliability for each substance category. The internal consistency of ratings for control cues was somewhat lower (.58 to .77) and is likely due to variability in specific content within these substance categories.

Specificity of Reactivity Ratings for Substance Cues by Substance Use History

Both arousal-control and cross-over response designs (Robbins and Ehrman, 1992) were utilized to examine the specificity of reactivity ratings for substance cues. Participants were grouped based on their history of substance use prior to their incarceration using information collected during clinical interviews used for admittance to the RDAP (see Methods section for details). Total Ns varied based on these grouping procedures for each substance category due to missing data (see Table 1 for summary). Greenhouse-Geisser corrected p-values are reported for all effects involving the within-subject cue content factor to control for potential violations of sphericity. Finally, Bonferoni corrections were applied to follow-up univariate analyses to adjust for Type I error inflation (6 ANOVAs for each interaction analysis, adjusted p=.008)

Arousal-control analysis

To examine hypothesis 1, and to rule out the potential confound that general arousal in response to stimuli enhances overall reactivity, we conducted Substance Use History X Cue Content mixed model ANOVA for each substance class, with substance use history as a between subjects factor and cue content (substance cues, food cues, and non-alcoholic drink cues) as the within-subjects factor. Ideally, participants should show differences in arousal to substance cues based on prior experience with such substance, but no differences in arousal to control cues (food and non-alcoholic drinks) or other substances.

As predicted, significant Cigarette Use X Cue Content interaction was observed, F(11.2, 452.3) = 5.64, p <.001, partial η2 = .12], with a significant linear trend for cigarette cues only, F(1, 121) = 102.67, p <.001, such that arousal ratings increased as a function of current cigarette use. With regard to arousal ratings for alcohol, a significant Alcohol Use X Cue Content interaction was also observed, F(7.7, 574.8) = 2.43, p <.01, partial η2 = .05. Follow-up analyses found that arousal ratings increased as a function of drinking experience (linear trend), F(1, 150) = 11.01, p <.001. No significant differences were found in arousal ratings for control or other drug cues.

A significant Marijuana Use X Cue Content interaction was also observed for marijuana arousal ratings, F(8.0, 600.9) = 8.43, p <.001, partial η2 = .10, with a significant linear trend for marijuana cues observed, F(1, 150) = 50.29, p <.001. Similarly, a significant Crack-Cocaine Use X Cue Content interaction was observed, F(7.9, 588.2) = 5.77, p <.001, partial η2 = .07, with significant differences found for crack-cocaine cues only, F(1, 149) = 22.49, p <.001. No significant differences were found in arousal ratings for control or other drug cue.

Approach and Avoidance Ratings

To test hypothesis 2, several Substance Use History X Cue Content mixed model ANOVAs were conducted with approach and avoidant ratings as dependent variables. The analyses examined whether approach and avoidance ratings for cues would vary between groups differing in self-reported levels of past use of that substance. Similar to the above analyses, Bonferoni corrected p-values for all follow-up analyses were are reported to control for type I error inflation (.05/6=.008).

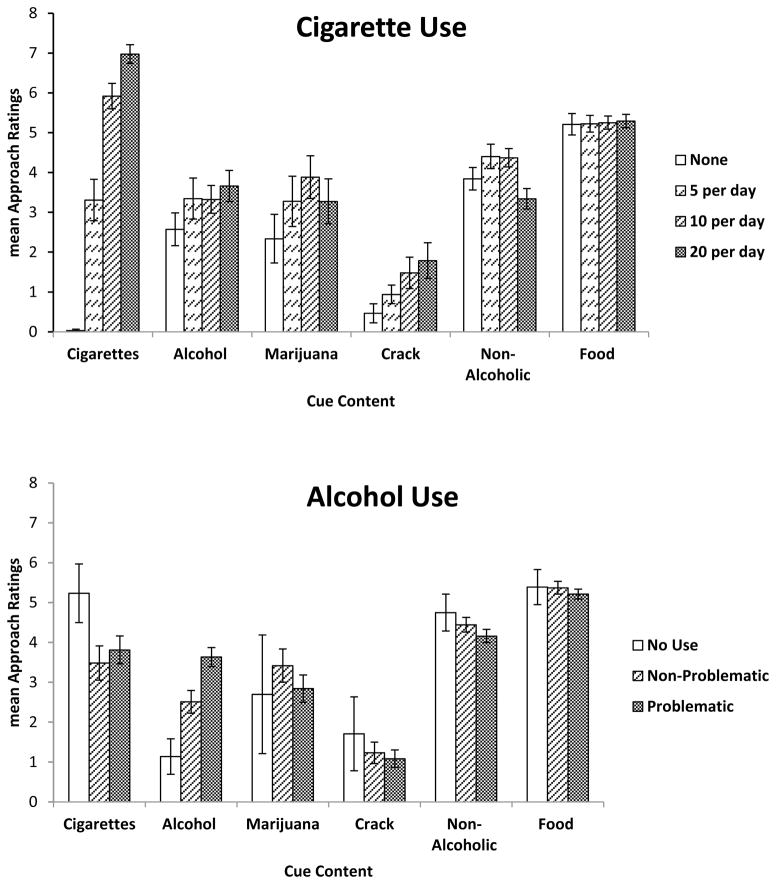

As predicted, a significant Cigarette Use X Cue Content interaction was observed, F(10.8, 434.3) = 10.32, p <.001, partial η2 = .20, for approach ratings (See Figure 1), with a linear trend found for cigarette cues only, F(1, 121) = 257.34, p <.001, such that approach ratings increased as a function of current cigarette use. In addition, a significant Cigarette Use X Cue Content interaction was also observed for avoidant ratings, F(10.9, 440.9) = 6.12, p <.001, partial η2 = .13, with significant differences found for cigarette cues only, F(1, 121) = 57.29, p <.001, such that avoidant ratings decreased as a function of current cigarette use.

Figure 1.

Arousal Control Analyses: Substance Use History X Cue Content Interactions for mean arousal ratings.

As predicted, a significant Alcohol Use X Cue Content interaction was observed for approach ratings, F(7.4, 556.9) = 2.14, p <.05, partial η2 = .03 (See Figure 2). Follow-up analysis revealed approach ratings increased as a function of drinking experience only, F(1, 150) = 14.22, p <.001. However, the Alcohol Use X Cue Content interaction was non-significant for avoidant ratings, F(7.2, 543.7) = .54, p=.81.

Figure 2.

Cigarette Use X Cue Content and Alcohol Use X Cue Content interactions for mean approach (top panels) and avoidance ratings (bottoms panels).

With regard to approach ratings for marijuana, as predicted a significant Marijuana Use X Cue Content interaction was observed, F(7.5, 560.6) = 9.10, p <.001, partial η2 = .11 (see Figure 3), with significant differences found for marijuana cues only, F(1, 150) = 66.69, p <.001, such that approach ratings increased as a function of history of marijuana use. Further, a significant Marijuana Use X Cue content interaction was observed for avoidant ratings, F(7.2, 541.0) = 4.55, p <.001, partial η2 = .06, with a linear trend observed for marijuana cues only, F(1, 150) = 30.16, p <.001, such that avoidant ratings decreased as a function of history of marijuana use.

Figure 3.

Marijuana Use X Cue Content and Crack-Cocaine Use X Cue Content interactions for mean approach (top panels) and avoidance ratings (bottoms panels).

Finally, a significant Crack-Cocaine Use X Cue Content interaction was also observed, F(7.5, 557.3) = 4.90, p <.001, partial η2 = .06, with significant differences found for crack-cocaine cues only, F(2, 149) = 18.03, p <.001. Specifically, a significant linear trend for crack-cocaine cues was observed, F(1, 149) = 31.90, p <.001, such that approach ratings increased as a function of crack-cocaine use. Further, a significant Crack-cocaine Use X Cue Content interaction was observed for avoidant ratings, F(7.4, 551.5) = 2.10, p <.05, partial η2 = .03. However, follow-up analyses found differences approaching significance for cigarette cues only, F(2, 143) = 4.22, p=.028.1

Incremental Validity: Relationship between Avoidance Ratings and Stages of Change Readiness

To examine hypothesis 3, several regression analyses were conducted to test whether avoidance ratings, after controlling for variance explained by approach ratings, would predict unique variance in measures of stages of change readiness (i.e., SOCRATES subscales). For each analysis, participants who indicated non-problematic and problematic use of the substance use under investigation (or daily cigarette use) were included in the analyses. Examination of the bivariate correlations revealed significant relationships between approach and avoidance ratings for cigarettes cues (r = −.49, p <.001), alcohol cues (r = −.46, p <.001), and marijuana cues (r = −.48, p <.001). No relationship was found between crack-cocaine approach and avoidance inclinations (r = −.10, ns).

To provide an index of the unique contribution of approach and avoidance ratings, semi-partial correlation coefficients from each regression analyses were examined (see Table 2 for summary). For cigarette ratings, significant relationships between approach ratings and problem recognition and ambivalence were observed, whereas avoidance ratings were significantly and uniquely related to taking steps to make a change. Results also indicated significant relationships between alcohol approach ratings and problem recognition, ambivalence, and taking steps to make a change, with avoidance ratings significantly and uniquely related to taking steps to make a change. Regarding marijuana use, approach ratings was significantly related to recognition of problems, ambivalence, and taking steps to make a change; however, no relationships were found for avoidance ratings. Finally, crack-cocaine approach ratings were significantly related to problem recognition and ambivalence, whereas avoidance inclinations demonstrated no significant relationships.

Table 2.

Incremental Validity Analyses for Avoidance Ratings (semi-partial correlations)

| Approach Ratings | Avoidance Ratings | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Cigarettes (n=95) | ||

| Problem Recognition | .35** | .06 |

| Ambivalence | .36** | .15 |

| Taking Steps | −.06 | .22* |

| Alcohol (n=147) | ||

| Problem Recognition | .41** | .14 |

| Ambivalence | .34** | .15 |

| Taking Steps | .38** | .20* |

| Marijuana (n=118) | ||

| Problem Recognition | .39** | −.04 |

| Ambivalence | .39** | −.04 |

| Taking Steps | .17 | −.16 |

| Crack-Cocaine (n=64) | ||

| Problem Recognition | .39** | −.04 |

| Ambivalence | .39** | −.04 |

| Taking Steps | .17 | −.16 |

p <.05,

p <.01

Discussion

The current study was designed to investigate the validity and reliability of using a pictorial cue exposure methodology to gather meaningful information about substance cue reactivity within a clinical sample of incarcerated female substance abusers. Specifically, we sought to validate the assessment of approach and avoidance inclinations as separate dimensions of reactivity. In addition, we extended this novel model of craving and cue reactivity paradigm to include two new illicit substances (marijuana and crack-cocaine), and then evaluated the model in a clinical sample of substance abusers in a novel setting.

The Ambivalence Model of Craving asserts that measuring avoidance reactivity as a separate response dimension will yield additional information beyond that obtained by measuring approach reactivity alone. Indeed, examination of participants’ approach and avoidance ratings demonstrated that some participants fell into each of the four quadrants of the “evaluative craving space” for each of the four drugs (see Table 1). The majority of those exhibiting either approach or ambivalent inclinations were found among those with problematic use prior to their incarceration. In addition, those exhibiting primarily avoidant inclinations were also found among those with problematic use, as well as non-problematic and minimal use. This pattern of dispersion is what one would expect to find when evaluating approach and avoidance reactivity among individuals with substance use disorders; potentially reflecting various stages of change.

Consistent with our first hypothesis, arousal control analyses demonstrated that differences observed between reactivity to drug related cues among groups varying in use of that substance was not due to increased arousability in general, but rather the result of direct experience of using the drug. For example, when participants were grouped by recent use of cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana, or crack-cocaine, differences emerged in levels of arousal for the respective substance but no differences were found for non-drug cues, such that greater experience resulted in higher arousal ratings. These findings are significant in that the control cues share many of the critical elements of the drug cues (e.g., consumability, sensory modality, desirability) and suggest that visual cues are a valid means of assessing for and differentiating among reactivity ratings for substances of abuse.

Results also indicated that approach and avoidance reactivity to cues for 6 of the 8 analyses (exceptions were for alcohol and crack-cocaine avoidance ratings) differed as a function of substance use experience (i.e., hypothesis 2). Moreover, the differences observed demonstrated specificity based on substance category. For example, when participants were grouped based on cigarette experience, differences in approach and avoidance reactivity to cigarette cues were observed, whereas no differences were found in reactivity patterns for other drug and food cues. Perhaps more importantly, incremental validity analyses indicated that avoidance inclinations significantly contributed to the prediction of the SOCRATES taking steps subscale for both alcohol and cigarette use above and beyond traditional approach ratings (i.e., hypothesis 3), a finding consistent with previous literature (Stritzke et al., 2004; Klein et al., 2007; Schlauch et al., 2012). Interestingly, no relationships were found for marijuana and crack-cocaine avoidance ratings. As this is the first study to examine both approach and avoidance inclinations across multiple substances of abuse, additional research is needed to fully understand these relationships, particularly the inclusion of additional measures related to substance use and treatment outcomes.

It’s worth noting that the relationship between avoidance inclinations and the SOCRATES ambivalence subscale was not significant. This is consistent with the Ambivalence Model of Craving, yet this seemingly counterintuitive finding may arise from different applications of the term “Ambivalence” within the craving model and the SOCRATES measure. Specifically, the former assesses ambivalence about whether or not to approach or avoid alcohol in response to internal or external cues and the latter assesses ambivalence about whether or not one has an alcohol problem and the uncertainty about problem behavior change (e.g., “Sometimes I wonder if I am an alcoholic”, “Sometimes I wonder if my drinking is hurting other people”). Indeed, the current findings, as well as findings from previous studies (e.g., Stritzke et al., 2004; McEvoy et al., 2004; Stritzke et al., 2007; Schlauch et al., 2012), suggest that the avoidance dimension of craving is more predictive of action oriented motivation and stages of change (e.g., taking steps to make a change, including action and maintenance stages) and likely serve to moderate the relationship between approach inclinations and drug use behavior.

Although inconsistent with our predictions, the lack differences in avoidance ratings for alcohol and crack-cocaine cues as a function of history of use may not be all that surprising given the substances under investigation, the context of the study (i.e., prison setting), and the treatment seeking status of participants. Avoidance ratings are thought to develop as a function of the negative consequences of use, and one could argue that both alcohol and crack-cocaine use are associated with greater immediate negative consequences than cigarettes and marijuana use (e.g., greater disinhibted behaviors associated with use), even among those with minimal and/or non-problematic use. With 66% of participants convicted of crimes related to drug use, and the remaining 34% convicted of crimes often associated with maintaining a drug habit (e.g., fraud, robbery, burglary, embezzlement), or as the result of association with a drug-related crime organization (e.g., money laundering, racketeering), higher avoidance ratings may be expected regardless of severity of use. Future research would benefit from understanding the factors associated with increased avoidance inclinations, including how consequences of use and other individual difference factors, such as personality and comorbid psychopathology, influence such ratings.

It is also possible that the higher avoidance ratings observed for alcohol and crack-cocaine cues when compared to control cues are the result of the study being conducted in a prison setting. The controlled prison environment differs from other contexts in which cue reactivity studies have been conducted and these differences may have significantly impacted the inmates’ responses to the alcohol and drug cues. For example, prison settings might influence reactivity response patterns due to the saliency of punishment cues associated with substance use. Additionally, inmates are made well aware of the severe penalties the prison imposes for use of drugs or alcohol within the prison. Therefore, the participants are surrounded by drug punishment cues, which could serve to enhance avoidance reactivity, particularly for substances that are associated with stronger negative consequences. Indeed, it has been speculated that proximity to reward cues combined with distance from punishment cues contributes to repeated relapse to substance abuse despite efforts to abstain from use (Breiner et al., 1999; Astin, 1962). The prison environment represents the opposite orientation; that is, proximity to punishment cues and distance from reward cues. Thus, it will be important for research to explore how the saliency of reward and punishment impact approach and avoidance dimensions of craving.

Finally, the treatment status of participants may also directly impact reactivity ratings. Recent studies examining self-report questionnaires of approach and avoidance inclinations towards alcohol suggest that higher avoidance ratings are associated with taking steps to make a change (Schlauch, Stasiewicz, Bradizza, Coffey, Gulliver, & Gudleski, 2012; Klein, Stasiewicz, Koutsky, Bradizza, & Coffey, 2007), and that such ratings remain relatively high during treatment (Schlauch et al., 2012). Further, previous research in non-clinical samples suggests that higher avoidance inclinations are associated with the action and maintenance stages of change for cigarette use (Stritzke, et al., 2004). Taken together, these findings suggest that changes in avoidance ratings may occur prior to entering treatment or the decision to make a change, and that our inability to detect differences among alcohol and crack-cocaine avoidance ratings as a function of use may be due, in part, to participants either receiving or seeking treatment. Nevertheless, significant associations above and beyond traditional approach inclinations were found between alcohol avoidance ratings and taking steps to make a change, suggesting a greater need to understand the role of avoidance inclinations in craving processes, particularly it’s role in the decision to make a change and seek treatment, as well as the impact on treatment outcomes.

Taken together results from the current study are consistent with findings in non-clinical college student (Stritzke et al., 2004) and adolescent (Curtin et al., 2005) samples, and provides support for measuring a separate, yet concurrent, avoidance dimension of craving in the study of substance use cue reactivity in clinical samples. However, there are several limitations that should be noted. First, generalizability for the current findings may be limited due to the unique population, namely incarcerated female substance abusers. Incarcerated females are a rarely studied population and as such, it is unclear how it may have impacted our findings or how such findings may generalize to other clinical populations. Further, the low n’s within some of our group classifications (e.g., no use/minimal use for alcohol) may have impacted our ability to find significant effects. Future research should explore how differences between (e.g., treatment-seeking versus non-treatment seeking) and within clinical populations (e.g., individual differences such as comorbidity) affect approach and avoidance inclinations. Unfortunately, our limited access to clinical interviews conducted by RDAP Drug Treatment Specialists hindered our ability to explore the impact of such individual differences on approach and avoidance inclinations. Nevertheless, the pattern of results seem to suggest similar craving processes observed in non-clinical samples, as well as clinical samples using self-report questionnaires (e.g., Schlauch et al., 2012; Klein et al., 2007; Stritzke et al., 2007). Second, the current study relied on self-report assessments of approach and avoidance in response to pictorial cues due to the setting in which the research was conducted. Future research on the validity of measuring approach and avoidance reactivity to substance cues would benefit from multi-method assessments, including physiological indices. Third, the prison environment may have significantly impacted inmates’ perceptions of alcohol and drug availability. This is important because, perceptions regarding the availability of a substance may diminish the strength of participants’ approach inclination toward that substance (e.g., Davidson, Tiffany, Johnston, Flury, & Li, 2003; Wertz & Sayette, 2001), although the literature has been somewhat mixed (e.g., Smith-Hoerter, Stasiewicz, & Bradizza, 2004). Perhaps concurrent assessments of avoidance inclinations may help explain these inconsistencies, as dampened approach reactivity seen in previous studies may actually be a function of heightened avoidance reactivity. Unfortunately, prison regulations prevented an assessment of participant perceptions of alcohol and drug availability in the prison. Future research is needed to investigate how manipulations in perceived availability directly impact both approach and avoidance dimensions of craving.

In summary, findings from the study provide considerable support for the measurement of both approach and avoidance dimensions of craving, and the incremental validity of separately measuring these two reactivity dimensions in those with diagnosable substance use disorders. Exploration of the role of the ambivalence model of craving in predicting substance use related outcomes, including their potential impact on treatment, provides many exciting avenues for investigators concerned with cue-elicited craving and it’s impact on substance use disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, grant T32-AA007583. We would also like to thank Dr. David Drobes for providing the crack-cocaine images used in the study.

Footnotes

The following variables were examined for potential effects of treatment on avoidance inclinations: 1) number of months in prison, 2) stages of change, and 3) treatment waitlist status. Findings for all analyses were unchanged; therefore, the most parsimonious models are presented in the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Robert C. Schlauch, Department of Psychology, Florida State University

Mary J. Breiner, Department of Psychology, Florida State University

Paul R. Stasiewicz, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Rita L. Christensen, Department of Psychology, Florida State University

Alan R. Lang, Department of Psychology, Florida State University

References

- Astin AW. “Bad habits” and social deviation: A proposed revision in conflict theory. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1962;18:227–231. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(196204)18:2<227::aid-jclp2270180236>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Morse E, Sherman JE. The motivation to use drugs: A Psychobiological analysis of urges. In: Rivers C, editor. The Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Vol. 34, Alcohol and addictive behavior. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1987. pp. 257–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper M, McCarthy D, Majeskie M, Fiore M. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiner MJ, Stritzke WGK, Lang AR. Approaching avoidance: a step essential to the understanding of craving. Alcohol Research and Health. 1999;23:197–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BL, Tiffany ST. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction. 1999;94:327–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Saladin ME, Drobes DJ, Dansky BS, Wieselquist J, Brady KT. The development of crack cocaine picture slides for cue reactivity studies: A preliminary normative study. Poster session presented at the 60th Annual Scientific Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence; Scottsdale, AZ. 1998. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Curtin JJ, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM. Cue reactivity in adolescents: measurement of separate approach and avoidance reactions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:332–343. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson D, Tiffany S, Johnston W, Flury L, Li TK. Using the cue-availability paradigm to assess cue reactivity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1251–1256. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080666.89573.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N. A conceptual framework for explaining drug addiction. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 1998;12:3–7. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AA, Stasiewicz PR, Koutsky JR, Bradizza CM, Coffey SF. A psychometric evaluation of the Approach and Avoidance of Alcohol Questionnaire (AAAQ) in alcohol dependent outpatients. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavior Assessment. 2007;4:231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ. The emotion probe: Studies of motivation and attention. American Psychologist. 1995;50:372–385. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.5.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International affective picture system (IAPS): Instruction manual and affective ratings. Gainesville, FL: Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Langan NP, Pelissier B. Gender differences among prisoners in drug treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:291–301. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan DS, Farabee D, Crouch BM. Early victimization, drug use, and criminality: A comparison of male and female prisoners. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1997;24:455–476. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy P, Stritzke WGK, French DJ, Lang A, Ketterman RL. Comparison of three models of alcohol craving in young adults: A cross-validation. Addiction. 2004;99:482–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Assessing drinkers’ motivation for change: The stages of change readiness and treatment eagerness scale (SOCRATES) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Niaura RS, Rohsenow DJ, Binkoff JA, Monti PM. Relevance of cue reactivity to understanding alcohol and smoking relapse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology Special Issue: Models of addiction. 1988;97:133–152. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orford J. Excessive appetites: A psychological view of addictions. 2. New York, NY: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Peters R, Strozier A, Murrin M, Kearns W. Treatment of substance-abusing jail inmates: Examination of gender differences. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1997;14:339–349. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelissier B, Camp S, Gaes G, Saylor W, Rhodes W. Gender differences in outcomes from prison-based residential treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24:149–160. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins SJ, Ehrman RN. Designing studies of drug conditioning in humans. Psychopharmacology. 1992;106:143–153. doi: 10.1007/BF02801965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette M, Shiffman S, Tiffany S, Niaura R, Martin C, Shadel W. The measurement of drug craving. Addiction. 2000;95:S189–S210. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlauch RC, Stasiewicz PR, Bradizza CM, Gudleski GD, Coffey SF, Gulliver SB. Relationship between approach and avoidance inclinations to use alcohol and treatment outcomes. Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.010. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Hoerter KE, Stasiewicz PR, Bradizza CM. Subjective reactions to alcohol cue exposure: A qualitative analysis of patients’ self-reports. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:402–406. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasiewicz PR, Maisto SA. Two-factor avoidance theory: The role of negative affect in the maintenance of substance use and substance use disorder. Behavior Therapy. 1993;24:337–356. [Google Scholar]

- Stritzke WGK, Breiner MJ, Curtin JJ, Lang AR. Assessment of substance cue reactivity: Advances in reliability, specificity, and validity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:148–159. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritzke WGK, McEvoy PM, Wheat LR, Dyer KR, French DJ. The yin and yang of indulgence and restraint: The ambivalence model of craving. In: O’Neal PW, editor. Motivation of health behavior. Nova Science Publishers, Inc; Hauppauge, New York: 2007. pp. 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J, de Wit H, Eikelboom R. Role of unconditioned and conditioned drug effects in the self-administration of opiates and stimulants. Psychological Review. 1984;91:251–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany S. A cognitive model of drug urges and drug-use behavior: Role of automatic and nonautomatic processes. Psychological Review. 1990;97:147–168. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz JM, Sayette M. Effects of smoking opportunity on attentional bias in smokers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15(3):268–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. Women and drug misuse. Issues in Forensic Psychology. 2001;2:29–34. [Google Scholar]