Abstract

Expression of the brown adipocyte-specific gene, uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), is increased by both PPARγ stimulation and cAMP activation through their ability to stimulate the expression of the PPAR coactivator PGC1α. In HIB1B brown preadipocytes, combination of the PPARγ agonist, rosiglitazone, and the cAMP stimulator forskolin synergistically increased UCP1 mRNA expression, but PGC1α expression was only increased additively by the two drugs. The PPARγ antagonist, GW9662, and the PKA inhibitor, H89, both inhibited UCP1 expression stimulated by rosiglitazone and forskolin but PGC1α expression was not altered to the same extent. Reporter studies demonstrated that combined rosiglitazone and forskolin synergistically activated transcription from a full length 3.1 kbp UCP1 luciferase promoter construct, but the response was only additive and much reduced when a minimal 260 bp proximal UCP1 promoter was examined. Rosiglitazone and forskolin in combination were able to synergistically stimulate promoters comprising of tandem repeats of either PPREs or CREs. We conclude that rosiglitazone and forskolin act together to synergistically activate the UCP1 promoter directly rather than by increasing PGC1α expression and by a mechanism involving cross-talk between the signalling systems regulating the CRE and PPRE on the promoters.

1. Introduction

Nonshivering thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue (BAT) in response to a cold environment is initiated by sympathetic neural stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors on brown adipocytes which elevate intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) and, via the protein kinase A (PKA) pathway, increase the expression and thermogenic activity of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) [1]. UCP1 is BAT specific and responsible for uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation by enabling protons to return to the mitochondrial matrix without ATP synthesis, thereby producing heat. UCP1 expressing BAT has recently been identified in humans and has been proposed as a target for activation to increase energy expenditure and prevent or treat obesity [2].

UCP1 expression has been suggested to be regulated by the cAMP-inducible peroxisome proliferator activated coactivator 1α (PGC1α) which interacts with a BAT determination factor, PRDM16, to increase the expression of a number of BAT-selective genes including Cidea [3]. We have also shown that the cAMP-inducible transcription factor C/EBPβ stimulates PGC1α expression in white and brown adipocytes by binding to the cAMP response element (CRE) on the PGC1α proximal promoter [4, 5] while others have demonstrated that PKA activation of PGC1α expression involves phosphorylation of p38 MAPK [6]. The PPARγ ligand, rosiglitazone increases expression of PGC1α [7, 8] acting on a distal PPRE which binds PPARγ/retinoid X receptor heterodimers and further positively autoregulates its own expression by coactivating PPARγ responsiveness to rosiglitazone [7]. Furthermore, C/EBPβ has been suggested to bind to PRDM16 to activate PGC1α expression during brown adipogenesis [9].

Therefore, UCP1 expression is thought to be regulated indirectly through an increased expression of PGC1α which then coactivates PPARγ transactivation of the PPRE on the UCP1 enhancer [6]. cAMP response elements (CREs) have also been identified in the proximal promoter and a distal enhancer of UCP1 [6, 10], but the relative roles of direct and indirect interactions with the UCP1 promoter are uncertain. Furthermore, few studies have examined the interaction between cAMP and PPARγ ligands. Here, we report that stimulation of the PKA and PPARγ signaling pathways synergistically and directly stimulates transcription from the UCP1 promoter, due to the cross-talk between the two pathways.

2. Methods

2.1. Plasmids

The firefly luciferase reporter gene constructs containing the 3.1 kbp or 260 bp upstream of mouse UCP1 transcription site were kind gifts from Leslie P. Kozak, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisana [10]. The 2.6 kbp PGC1α-pGL3-Luc containing 2600 bp insert size between +78 and −2533 with respect to mouse transcript start site was purchased from Addgene (UK), and the 264 bp (264 PGC1α-pGL3) from the region upstream of the rodent Pgc-1α transcription start site ligated to the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega) has been described [4]. The CRE positive vector (4 × CRE-Luc) that contains four repeat copies of the consensus CRE sequence upstream of a TATA box to drive expression of the firefly luciferase gene was purchased from Stratagene. The PPRE positive vector consisting of mouse PPRE × 3-TK-luc containing 3 direct repeat (DR1) of response elements (AGGACAAAGGTCA) upstream of a luciferase gene was purchased from Addgene (UK). The −2253-CRE-mut-PGC1α-Luc promoter construct was kindly given by F. Villarroya (University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain). The −2253-CRE-mut-PGC1α-Luc contains a point mutation at −146/−129 which was obtained by digestion of −2553-PGC1α-Luc with PvuII and ZraI and further ligation [7].

2.2. Cell Culture, Transfections, and Luciferase Assays

HIB-1B cells (kindly provided by B. Spiegelman) were maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS (Invitrogen) in 5% CO2. For transfections, HIB-1B cells were cultured to 80% confluence and then were transfected with pGL3 luciferase plasmids using Fugene 6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The pRL-SV40 construct (Promega) that carries renilla luciferase gene was cotransfected as an internal control for monitoring the transfection efficiency. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated with DMSO (control), rosiglitazone (10 μM) for 24 hours, or forskolin (10 μM) for the final 12 hours of rosiglitazone treatment, in serum-free medium, before luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase assay kit (Promega), as recommended by the manufacturer. Values were normalised relative to the renilla signal to allow for differences in transfection efficiency.

For mRNA expression studies, HIB-1B cells were grown to confluence and then treated with H89 (10 μM) for 1 hour or GW9662 (30 μM) for 3 hours prior to and during addition of rosiglitazone (Rosi) (10 μM) for 24 hours or forskolin (Fosk) (10 μM) for the final 3 hours of rosiglitazone treatment, before RNA extraction, as indicated. All drugs were added in serum-free medium. Controls were treated with DMSO.

2.3. Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using TRI reagent (Sigma). Prior to RT-PCR, samples were treated with RNase-free DNase to remove contaminating genomic or plasmid DNA. cDNA was generated using the cDNA synthesis kit from Qiagen. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using Sybr green according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche). The sequences of the primers used for real-time PCR are given in Table 1. Expression levels for all genes were normalized to expression of the house keeping gene, 36B4.

Table 1.

The sequences of primers for the real-time PCR.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| PGC1α | TGAGAGACCGCTTTGAAGTTTTT | CAGGTGTAACGGTAGGTGATGAAA |

| PRDM16 | TCTTACTTCTCCGAGATCCGAAA | GATCTCAGGCCGTTTGTCCAT |

| C/EBPβ | AGCGGCTGCAGAAGAAGGT | GGCAGCTGCTTGAACAAGTTC |

| UCP1 | GCCATCTGCATGGGATCAA | GGTCGTCCCTTTCCAAAGTG |

| PPARγ | GTGCCAGTTTCG ATCCGT AGA | GGCCAGCATCGTGTAGATA |

| aP2 | AACACCGAGATTTCC | ACACATTCCACCACCAG |

| Cidea | ACAGAAATGGACACCGGGTAGT | CGAAGGTGACTCTGGCTATTCC |

| 36B4 | TCCAGGCTTTGGGCATCA | TTATCAGCTGCACATCACTCAGAAT |

2.4. Statistical Analysis

To examine the effects of agonists (forskolin, rosiglitazone) and antagonists (GW9662, H89) as well as interaction effects (agonists × antagonists) on mRNA levels or luciferase reporter activities of all groups, a two-way ANOVA (SPSS, v17) was performed. The comparisons between agonist and agonist + antagonist treated cells or between wildtype 2.6 kb PGC1α-Luc and CRE-mut-PGC1α-Luc transfected cells were determined by t test.

3. Results

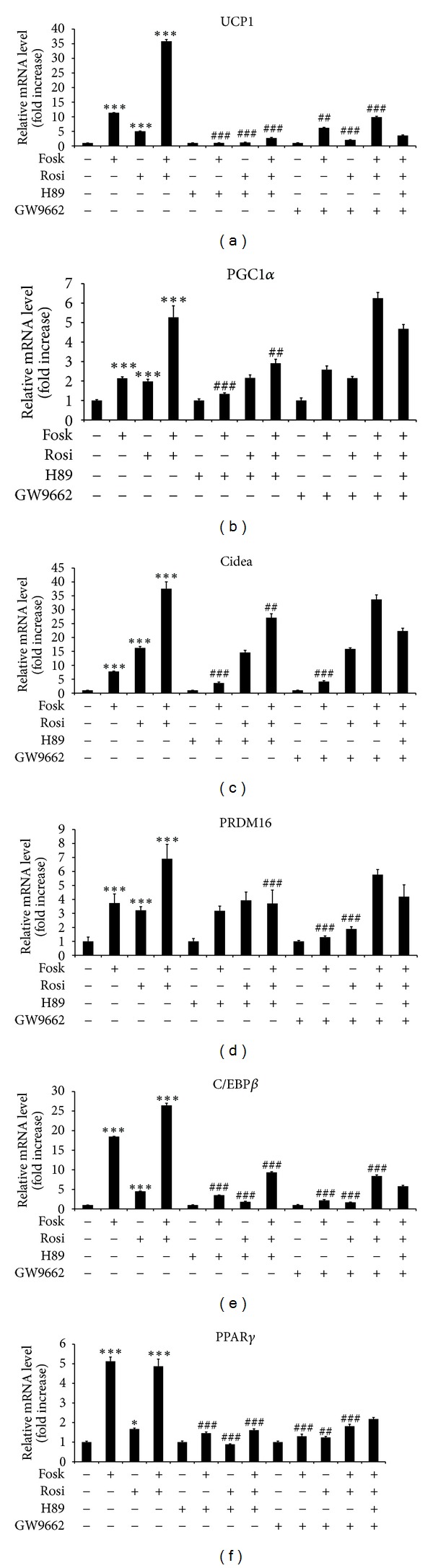

3.1. Synergistic Increase in UCP1, but Not PGC1α, Cidea, or PRDM16 in Response to Combined Forskolin and Rosiglitazone Is Inhibited by a PKA Inhibitor (H89) and a PPARγ Antagonist (GW9662)

Addition of forskolin for 3 h and rosiglitazone for 24 h increased UCP1 mRNA expression by 12-fold (P < 0.001) and 5.5-fold (P < 0.001), respectively, but when forskolin was added during the last 3 h of incubation with rosiglitazone, a synergistic 40-fold increase (P < 0.001) was observed, relative to control confluent HIB1B cells (Figure 1(a)). Addition of the PKA inhibitor H89 significantly increased by 4-fold (P < 0.001) the basal expression of UCP1 mRNA but completely blocked the stimulatory effect of forskolin (P < 0.001) and inhibited the synergistic response to forskolin plus rosiglitazone by 75% (P < 0.001). H89 also suppressed the UCP1 mRNA response to rosiglitazone by 75% (P < 0.001). The PPARγ antagonist GW9662 doubled the basal levels of UCP1 mRNA but inhibited the response to forskolin and rosiglitazone by 50–75% (P < 0.001). A mixture of GW9662 and H89 decreased UCP1 mRNA by 88% in response to forskolin plus rosiglitazone, relative to control cells (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

The effect of forskolin and rosiglitazone on mRNA expression of (a) UCP1, (b) PGC1α, (c) Cidea, (d) PRDM16, (e) C/EBPβ, and (f) PPARγ is mediated by PKA and PPARγ dependent pathways. HIB-1B cells were grown to confluence and then treated with H89 (10 μM) for 1 hour or GW9662 (30 μM) for 3 hours prior to and during addition of rosiglitazone (Rosi) (10 μM) for 24 hours, or forskolin (Fosk) (10 μM) for the final 3 hours of rosiglitazone treatment, before RNA extraction, as indicated. All drugs were added in serum-free medium. Controls were treated with DMSO. Gene expression levels were analysed by quantitative real-time PCR and normalized against 36B4 expression. Error bar means the mean ± SEM of triplicate observations within a single experiment performed in triplicate. *** Significant difference P < 0.001 with respect to control; ### significant difference P < 0.001 due to H89 or GW9662 for each experiment.

In contrast, PGC1α mRNA was upregulated two-fold by forskolin or rosiglitazone treatment (P < 0.001; Figure 1(b)) and only additively by combined forskolin and rosiglitazone treatment. Addition of H89 downregulated the PGC1α expression response to forskolin by 77% (P < 0.001), but surprisingly, addition of GW9662 did not alter PGC1α expression in the presence of forskolin, or rosiglitazone, separately or in combination. These results suggested that the action of cAMP and PPARγ stimulation on the initiation of UCP1 expression was directly targeting UCP1 rather than indirectly acting on PGC1α expression.

We next examined whether the brown selective genes Cidea and PRDM16 were responsive to PKA and PPARγ modulation. Similar to UCP1, expression of Cidea was increased by both forskolin (P < 0.001) and rosiglitazone (P < 0.001) by 8-fold and 18-fold, respectively, and when forskolin and rosiglitazone were combined together, there was a synergistic 40-fold stimulatory effect (P < 0.001) relative to control cells (Figure 1(c)). In contrast to UCP1, although H89 caused a significant 65% reduction (P < 0.001) in Cidea expression in response to forskolin, there was no effect of H89 on Cidea expression in response to rosiglitazone and only a small 25% inhibition of the response to combined forskolin plus rosiglitazone (P < 0.01) was observed. Furthermore, GW9662 did not alter Cidea expression in response to rosiglitazone or forskolin plus rosiglitazone although forskolin stimulated Cidea expression was suppressed by 21% (P < 0.01). Again in contrast to UCP1, PRDM16 mRNA levels were induced by only 3-fold (P < 0.001) in response to forskolin or rosiglitazone and only additively in response to forskolin plus rosiglitazone (P < 0.001) (Figure 1(d)), relative to control cells. Addition of H89 did not alter the response to either forskolin or rosiglitazone, but the response to combined forskolin and rosiglitazone was inhibited by 58% (P < 0.05). Addition of the PPARγ antagonist, GW9662, inhibited PRDM16 expression in response to either forskolin or rosiglitazone by 56–60% (P < 0.001), but GW9662 failed to inhibit the PRDM16 response to forskolin and rosiglitazone in combination. Expression of the adipogenic differentiation marker gene aP2, in response to stimulation by forskolin and rosiglitazone, was similarly less sensitive to H89 and GW9663, compared to UCP1 (results not shown). These results again suggest that the action of cAMP and PPARγ stimulation on the initiation of UCP1 expression was directly targeting the UCP1 promoter.

3.2. Effect of a PKA Inhibitor (H89) and a PPARγ Antagonist (GW9662) on C/EBPβ and PPARγ Expression in Response to Forskolin and Rosiglitazone Is Different to Responses Observed on UCP1

Our attention was then drawn to the effect of rosiglitazone and forskolin on the expression of C/EBPβ and PPARγ, genes which have been reported to regulate UCP1 expression. C/EBPβ mRNA was increased by 18-fold (P < 0.001) in response to forskolin and 4.5-fold (P < 0.001) in response to rosiglitazone, relative to control cells (Figure 1(e)). In addition, a 26-fold additive response to combined forskolin and rosiglitazone (P < 0.01) in C/EBPβ mRNA was observed. H89 blocked forskolin stimulated C/EBPβ expression by 82% (P < 0.001), rosiglitazone induced expression by 32% (P < 0.01), and the combined effect of forskolin plus rosiglitazone was inhibited by 68% (P < 0.001). GW9662 blocked forskolin stimulated C/EBPβ expression by 93% (P < 0.001), rosiglitazone induced C/EBPβ expression by 49% (P < 0.01), and inhibited the additive activation by forskolin and rosiglitazone combination on C/EBPβ expression by 50% (P < 0.001).

PPARγ mRNA was increased by 5.2-fold (P < 0.001) in response to PKA activation with forskolin and 1.7-fold (P < 0.05) by rosiglitazone, but there was no further response when forskolin and rosiglitazone were combined (Figure 1(f)). Addition of H89 significantly decreased the response to forskolin by 70% (P < 0.001). GW9662 reduced PPARγ expression by 90% (P < 0.001) in response to forskolin and by 73% (P < 0.001) and 70% (P < 0.001), respectively, in response to rosiglitazone and forskolin plus rosiglitazone, respectively.

Therefore, the expression of PPARγ and C/EBPβ was predominantly increased by forskolin with only a small effect of combining forskolin and rosiglitazone, but these effects could be suppressed by both PKA inhibition (H89) and the PPARγ antagonist GW9662. Combined the results suggest that the effects of the inhibitors and stimulators on UCP1 expression could not be completely explained by changes in the expression of regulatory genes measured. Similar conclusions were drawn when expression levels of CtBP1, CtBP2, and RIP140 were measured (result not shown).

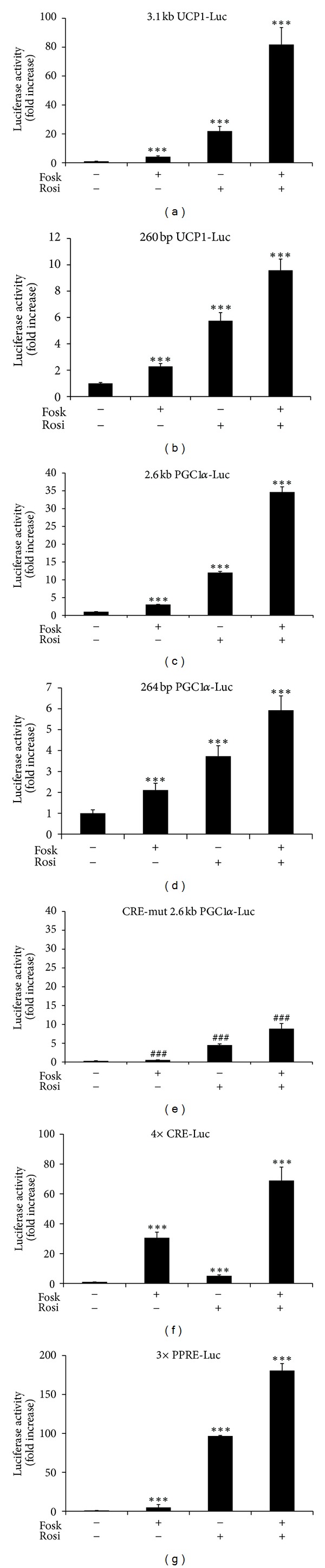

3.3. Synergistic Activation of UCP1 and PGC1α Transcription by Combined Forskolin and Rosiglitazone Requires the Full Length Promoters

We next examined the effect of PKA and PPARγ activation on full length and truncated UCP1 and PGC1α promoter luciferase reporter constructs transfected into confluent HIB1B cells. Addition of rosiglitazone for 24 h or forskolin for 12 h significantly induced transcriptional activity of the full length 3.1 kb UCP1 promoter reporter construct by 22-fold and 4.1-fold (P < 0.001), respectively, and when the drugs were combined, synergistically increased transcription by 82-fold (Figure 2(a); P < 0.001). By comparison, transcription from the proximal 260 bp UCP1 promoter was only stimulated 2-fold and 6-fold, by forskolin and rosiglitazone, respectively (P < 0.001), and combined addition of the two drugs increased reporter activity by 10-fold (P < 0.001; Figure 2(b)). The 260 bp promoter contains only one CRE, no PPRE, but is activated by forskolin to approximately the same extent, as the 3.1 kb UCP1 promoter reporter construct [11].

Figure 2.

Luciferase reporter assay showing the effect of forskolin and rosiglitazone on (a) 3.1 kbp UCP1-Luc, (b) 260 bp UCP1-Luc, (c) 2.6 kbp PGC1α-Luc, (d) 264 bp PGC1α-Luc, (e) CRE-mut 2.6 kbp PGC1α-Luc, (f) 4 × CRE-Luc, and (g) 3 × PPRE-Luc, promoter activities. HIB-1B cells were grown to confluence and then transiently transfected with the above -pGL3-Luc reporter construct, as indicated. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated with DMSO (control), rosiglitazone (10 μM) for 24 hours, or forskolin (10 μM) for the final 12 hours of rosiglitazone treatment, in serum-free medium, before luciferase activity was measured. Values were expressed as fold increase of ratio of firefly to renilla. Error bar means the mean ± sem. of three observations within a single experiment performed in triplicate. *** Significant difference P < 0.001, respectively, with respect to control; ### significant difference P < 0.001 from wildtype due to the mutation of CRE.

We next examined a PGC1α-Luc promoter reporter. Forskolin addition significantly doubled (P < 0.001) transcription from the full length 2.6 kb PGC1α promoter while addition of rosiglitazone stimulated by 12-fold (P < 0.001; Figure 2(c)). When forskolin and rosiglitazone were combined together, there was a synergistic 35-fold increase in the 2.6 kb PGC1α transcription activity (P < 0.001). As observed with the proximal UCP1 promoter, there were significant (P < 0.001) effects of forskolin and rosiglitazone, alone or in combination, on transcription from the proximal 264 bp PGC1α-Luc minimal promoter, even though this contains only a CRE and no PPRE [4], but transcription activities and fold responses were 3–6-fold less compared with the full length 2.6 kb PGC1α-Luc (Figure 2(d)). Mutation of the CRE on the 2.6 kb PGC1α promoter significantly decreased both basal expression and the response to forskolin and rosiglitazone, alone or in combination, by between 63% and 80% (P < 0.001), compared to wildtype 2.6 kb PGC1α (Figure 1(g)).

When reporter constructs under the control of promoters containing repeats of either CRE (4 × CRE-Luc) or PPRE (PPRE × 3-Luc) were examined, as expected, forskolin stimulated mainly the CRE-Luc and rosiglitazone stimulated the PPRE-Luc (P < 0.001; Figures 2(e) and 2(f)). However, there was significant stimulation of the PPRE-Luc by forskolin (P < 0.001), of the CRE-Luc by rosiglitazone (P < 0.001), and a synergistic response to combined forskolin plus rosiglitazone for both the CRE-Luc and PPRE-Luc (P < 0.001; Figures 2(e) and 2(f)). These results clearly suggest that the synergistic response in the UCP1 promoter activity to combined forskolin and rosiglitazone involves interaction between pathways targeting the CREs and PPREs on the UCP1 promoter.

4. Discussion

Expression of UCP1 in brown adipocytes can be induced in vitro and in vivo by drugs that activate PKA and PPARγ, but few studies have examined the interaction between these pathways. This study compares the expression of a number of brown adipogenic genes in response to PKA and PPARγ stimulators and inhibitors in brown HIB-1B preadipocytes and demonstrates that the synergistic induction of UCP1 expression by combined PKA activation and PPARγ agonist treatment involves cross-talk between these pathways. This conclusion is based on the abilities of a PKA inhibitor to suppress responses to the PPARγ agonist and inhibition of PKA stimulation by a PPARγ antagonist. The responses of other brown adipogenic genes (Cidea, aP2) and regulators of brown adipogenesis (PGC1α, PRDM16, PPARγ C/EBPβ) to PKA or PPARγ activation/inhibition were different from UCP1, and, combined with reporter studies, we provide evidence that these responses to PKA activation and the PPARγ agonist treatment are targeted at the UCP1 promoter.

Combined addition of forskolin plus rosiglitazone resulted in a robust synergistic induction of UCP1 mRNA expression in undifferentiated confluent HIB-1B cells. A previous study was able to demonstrate a synergistic response in UCP1 and PGC1α expression to acute (2 hours) noradrenaline and chronic (continuously in the culture medium) rosiglitazone in differentiated mouse primary brown adipocytes [12]. Our luciferase reporter studies demonstrated that this synergistic response required the full length 3.1 kbp UCP1 promoter containing both the enhancer and proximal promoter elements since a reporter construct containing only the proximal 260 bp promoter was nearly 10-fold less responsive, and stimulation by forskolin + rosiglitazone was only additive. The stimulatory effect of rosiglitazone on the proximal UCP1 promoter was greater than forskolin despite this construct containing only a CRE and no PPRE. The ability of rosiglitazone to stimulate transcription at CREs was confirmed using an artificial promoter reporter containing tandem CRE repeats, as well as a 264 bp PGC1α proximal promoter reporter, neither of which contain a PPRE. Furthermore, when the CRE on the PGC1α 2.6 kbp promoter was mutated, there was a marked diminution of the responses both to rosiglitazone alone and combined forskolin + rosiglitazone. A previous study [13] using a reporter construct containing the 220 bp enhancer linked to a 73 bp minimal UCP1 promoter reporter construct similarly observed synergistic activation by combined PPARγ agonist and dibutyryl cAMP, but no responses were observed with the 73 bp minimal promoter which does not contain a CRE. Furthermore, the increase in UCP1 mRNA expression by rosiglitazone treatment was abolished by the PKA inhibitor, H89, and this effect was greatest when forskolin was added in combination. This inhibitory effect of H89 on gene expression in response to rosiglitazone appeared to be greatest for UCP1 and was not observed to the same extent with other genes involved in brown adipogenesis (Cidea, PRDM16, C/EBPβ, and PGC1α). The evidence therefore suggests that rosiglitazone-stimulated UCP1 expression, which is synergistically increased by forskolin, is at least partly due to increased activation of the CREs.

The mechanism by which rosiglitazone is able to stimulate the PKA pathway is not known. Rosiglitazone is a PPARγ ligand which increases the interaction of PPARγ with coactivators such as steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1) and p300/CBP (CREB binding protein) containing histone acetyl transferase activity, which is important for remodelling chromatin to increase the transcriptional activity of nuclear receptors [14]. GW9662 blocks the recruitment of these coactivators [14], and therefore the stimulatory effect of rosiglitazone on transactivation at the CRE may be caused by chromatin remodelling. In the present study, rosiglitazone strongly stimulated an artificial reporter containing tandem PPREs and in the study of [13], mutation of the PPRE on the UCP1 enhancer abolished responses to both PKA activation and a PPARγ agonist. However, there has been a report in primary brown adipocytes that rosiglitazone stimulates p38 MAPK phosphorylation in a non-PPARγ manner [8] which would explain why the expression of PGC1α appeared to be induced by rosiglitazone even in the presence of GW9662 (Figure 1(b)). PKA-dependent stimulation of PGC1α expression has been shown to involve p38-MAPK-dependent phosphorylation of ATF2 [6, 10]. Therefore, rosiglitazone activation of p38 MAPK would be likely to increase ATF2 phosphorylation and stimulate transcription from the CREs in the PGC1α promoter, as suggested for the effects of PKA activation.

The ability of rosiglitazone to stimulate the PPRE-Luc reporter activity was markedly stimulated by addition of forskolin, suggesting that increasing PKA activity was able to synergise with rosiglitazone by increasing transactivation of the PPRE on the UCP1 and PGC1α promoters. This proposal was supported by evidence that forskolin stimulation of UCP1 mRNA expression was partly decreased by addition of the PPARγ antagonist GW9662. Recently, it has been demonstrated that β-adrenergic agonist stimulation of UCP1 expression in HIB-1B cells is associated with an increase in PGC1α and PPARγ binding to the PPRE on the UCP1 enhancer [15]. PKA induced binding of C/EBPβ to the PPARγ2 promoter during adipogenesis is known to increase chromatin accessibility of transcription factors to the promoter [16], emphasising the importance of chromatin remodelling in transcriptional responses to PKA stimulation. Further studies are required to establish functional crosstalk between the pathways targeting the CREs and PPREs on the UCP1 promoter, for example, knocking down PPARγ or C/EBPβ expression to establish if this blocks induction by forskolin or rosiglitazone, respectively.

In the present study, forskolin stimulated PGC1α expression by activating PKA as indicated by the complete suppression with H89, and the stimulatory effect of forskolin was almost totally blocked when the CRE in the proximal promoter reporter construct was mutated, in agreement with previous reports [6, 7]. Forskolin also induced the expression of PPARγ and C/EBPβ, in a PKA-dependent manner which is consistent with their role as transcription factors stimulating both UCP1 and PGC1α expression [4, 6, 7, 9]. C/EBPβ, which is enriched in BAT compared to WAT, is sensitive to cold stimulation in BAT and forskolin treatment in HIB-1B cells, has been proposed to play a key role in the cAMP induction of UCP1 and PGC1α expression in a white adipocyte cell line [4, 9]. Therefore, our data showing that C/EBPβ expression is cAMP dependent and blunted by H89 is in accordance with previous studies. C/EBPβ and PRDM16 have been shown to form a transcriptional complex which increases PGC1α and UCP1 expression [9]. However, the pattern of expression responses of PGC1α, C/EBPβ, PPARγ, and PRDM16 to combined PKA stimulation and PPARγ agonist/antagonist treatment was generally different from responses in UCP1 expression, suggesting that changes in the expression of these regulators were not major factors in the control of UCP1 transcription. This notion was supported by our time course studies demonstrating that forskolin stimulated UCP1 expression in confluent undifferentiated HIB-1B cells within 24 hours while changes in PGC1α, C/EBPβ, and PRDM16 expression were either delayed for 72 hours or absent (results not shown). The control of UCP1 expression has previously been dissociated from that of PGC1α in β1/β2/β3-adrenoceptor knockout (β-less) brown adipocytes in primary culture [17]. Furthermore, in PGC1α depleted cells, the amounts of several brown fat-selective genes are not affected [18] supporting a role for PGC1α as a coactivator of PPARγ in response to cold but not for brown adipose differentiation.

The synergistic effects of combined PPARγ agonist and PKA stimulation on UCP1 expression appear to be physiologically relevant as surgical denervation of BAT pads in rats prevented maximal brown adipogenic gene expression in response to chronic rosiglitazone treatment [19]. Furthermore, PPARγ ligand treatment can increase UCP1 and PGC1α expression in rodent white adipose depots [20] or preadipocytes from WAT in mice [21] and humans [22].

5. Conclusions

The synergistic stimulation of UCP1 expression by combined forskolin and rosiglitazone appears to be directly targeting the UCP1 promoter and involves cross-talk between their PKA and PPARγ signalling systems. This study suggests that treating obesity by increasing energy expenditure as a result of brown adipose thermogenesis is more likely to be successful by combined drug therapy aimed at stimulating both PKA and PPARγ signalling pathways.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC). H. Y. Chen was supported by a scholarship from the Taiwanese Government and Q. Liu was supported by a China Scholarship (The University of Nottingham).

Abbreviations

- CRE:

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element

- BAT:

Brown adipose tissue

- WAT:

White adipose tissue

- UCP-1:

Uncoupling protein-1

- PPRE:

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor response element

- PGC-1:

Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivator 1.

References

- 1.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiological Reviews. 2004;84(1):277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boss O, Farmer SR. Recruitment of brown adipose tissue as a therapy for obesity-associated diseases. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2012;3(article 14) doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, et al. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature. 2008;454(7207):961–967. doi: 10.1038/nature07182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karamanlidis G, Karamitri A, Docherty K, Hazlerigg DG, Lomax MA. C/EBPβ reprograms white 3T3-L1 preadipocytes to a brown adipocyte pattern of gene expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(34):24660–24669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karamitri A, Shore AM, Docherty K, Speakman JR, Lomax MA. Combinatorial transcription factor regulation of the cyclic AMP-response element on the Pgc-1α promoter in white 3T3-L1 and brown HIB-1B preadipocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(31):20738–20752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao W, Daniel KW, Robidoux J, et al. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is the central regulator of cyclic AMP-dependent transcription of the brown fat uncoupling protein 1 gene. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2004;24(7):3057–3067. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.3057-3067.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hondares E, Mora O, Yubero P, et al. Thiazolidinediones and rexinoids induce peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-coactivator (PGC)-1α gene transcription: an autoregulatory loop controls PGC-1α expression in adipocytes via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivation. Endocrinology. 2006;147(6):2829–2838. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teruel T, Hernandez R, Benito M, Lorenzo M. Rosiglitazone and retinoic acid induce uncoupling protein-1 (UCP-1) in a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent manner in fetal primary brown adipocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(1):263–269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207200200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kajimura S, Seale P, Kubota K, et al. Initiation of myoblast to brown fat switch by a PRDM16-C/EBP-β transcriptional complex. Nature. 2009;460(7259):1154–1158. doi: 10.1038/nature08262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rim JS, Kozak LP. Regulatory motifs for CREB-binding protein and Nfe212 transcription factors in the upstream enhancer of the mitochondrial uncoupling protein 1 gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(37):34589–34600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shore A, Karamitri A, Kemp P, Speakman JR, Lomax MA. Role of Ucp1 enhancer methylation and chromatin remodelling in the control of Ucp1 expression in murine adipose tissue. Diabetologia. 2010;53(6):1164–1173. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1701-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrovic N, Shabalina IG, Timmons JA, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Thermogenically competent nonadrenergic recruitment in brown preadipocytes by a PPARγ agonist. American Journal of Physiology. 2008;295(2):E287–E296. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00035.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tai TAC, Jennermann C, Brown KK, et al. Activation of the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ promotes brown adipocyte differentiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(47):29909–29914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakano R, Kurosaki E, Yoshida S, et al. Antagonism of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ prevents high-fat diet-induced obesity in vivo. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2006;72(1):42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tateishi K, Okada Y, Kallin EM, Zhang Y. Role of Jhdm2a in regulating metabolic gene expression and obesity resistance. Nature. 2009;458(7239):757–761. doi: 10.1038/nature07777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xue Y, Petrovic N, Cao R, et al. Hypoxia-independent angiogenesis in adipose tissues during cold acclimation. Cell Metabolism. 2009;9(1):99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lehr L, Canola K, Asensio C, et al. The control of UCP1 is dissociated from that of PGC-1α or of mitochondriogenesis as revealed by a study using β-less mouse brown adipocytes in culture. FEBS Letters. 2006;580(19):4661–4666. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kajimura S, Seale P, Spiegelman BM. Transcriptional control of brown fat development. Cell Metabolism. 2010;11(4):257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Festuccia WT, Blanchard PG, Richard D, Deshaies Y. Basal adrenergic tone is required for maximal stimulation of rat brown adipose tissue UCP1 expression by chronic PPAR-γ activation. American Journal of Physiology. 2010;299(1):R159–R167. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00821.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vernochet C, Peres SB, Davis KE, et al. C/EBPα and the corepressors CtBP1 and CtBP2 regulate repression of select visceral white adipose genes during induction of the brown phenotype in white adipocytes by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2009;29(17):4714–4728. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01899-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrovic N, Walden TB, Shabalina IG, Timmons JA, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct from classic brown adipocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(10):7153–7164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.053942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiraby C, Tavernier G, Lefort C, et al. Acquirement of brown fat cell features by human white adipocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(35):33370–33376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]