Abstract

The literature on PTSD and metabolic disease risk factors has been limited by lacking investigation of the potential influence of commonly comorbid disorders and lacking consideration of the role of race. Data were provided by a sample of 134 women (63 PTSD and 71 without PTSD). Separate sets of models examined associations of psychiatric disorder classifications with metabolic disease risk factors. Each model included race (African American or Caucasian), psychiatric disorder, and their interaction. There was an interaction of race and PTSD on body mass index, abdominal obesity, and triglycerides. While PTSD was not generally associated with deleterious health effects in African American participants, PTSD was related to worse metabolic disease risk factors in Caucasians. MDD was associated with metabolic disease risk factors, but there were no interactions with race. Results support the importance of race in the relationship between PTSD and metabolic disease risk factors. Future research would benefit from analysis of cultural factors to explain how race might influence metabolic disease risk factors in PTSD.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress disorder, metabolic disease, race/ethnicity, obesity, major depressive disorder

Introduction

An increasingly large body of literature and epidemiologic evidence suggest a close relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and physical health (Schnurr & Green, 2004). Research has shown that individuals with PTSD report more health complaints, suffer from more physician-diagnosed medical conditions (Beckham, et al., 1998; Calhoun, Wiley, Dennis, & Beckham, 2009), and exhibit higher rates of health care utilization (Boscarino, 1997; Dennis, et al., 2009). PTSD has been linked with several health outcomes related to metabolic abnormalities including increased rates of metabolic syndrome (Babic, et al., 2007; Jakovljevic, et al., 2007; Jakovljevic, Saric, Nad, Topic, & Vuksan-Cusa, 2006; Violanti, et al., 2006), and higher rates of obesity (David, Woodward, Esquenazi, & Mellman, 2004; Dobie, et al., 2004; Perkonigg, Owashi, Stein, Kirschbaum, & Wittchen, 2009; Trief, Ouimette, Wade, Shanahan, & Weinstock, 2006; Vieweg, et al., 2007).

Although the literature on PTSD and metabolic disease risk factors has provided a number of notable findings, this literature is complicated by the frequent comorbidity of major depressive disorder (MDD) and substance use disorders (SUD) (Campbell, et al., 2007). In the National Comorbidity Survey, 49% of women with PTSD also reported a history of a major depressive episode (Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995). The association of MDD with poor physical health, including metabolic disease risk factors, has been observed in several decades of research (Eaton, 1996; Katon & Ciechanowski, 2002). In addition to MDD, PTSD is often accompanied by comorbid SUD. In the National Comorbidity Survey, 28% of women with PTSD also reported a history of comorbid alcohol abuse or dependence, and 27% reported a history of drug abuse or dependence (Kessler, et al., 1995). Several studies have noted an association between SUD and metabolic disease (Virmani, Binienda, Ali, & Gaetani, 2006). SUD has been linked with poor glycemic control (Ng, Darko, & Hillson, 2004) and more severe diabetes (Glasgow, et al., 1991).

Studies estimate the lifetime prevalence of PTSD in the United States is between 6% and 8% (Kessler, et al., 2005), and is twice as high in women as in men (Breslau, 2001), with estimates ranging from 10% to 13% (Calhoun, et al., 2009). Further, women are twice as likely to develop PTSD following trauma exposure and are more likely to develop chronic symptoms of PTSD (Calhoun, et al., 2009). Unfortunately, much of the research on PTSD and physical health has occurred with samples that are primarily or exclusively male. While much of the research on PTSD and physical health has been conducted in men, some research supports the generalizability of this association to female samples. Studies have shown that women with PTSD exhibit a higher resting heart rate compared to those without PTSD (Beckham, Flood, Dennis, & Calhoun, 2009; Vrana, Hughes, Dennis, Calhoun, & Beckham, 2009), and exaggerated heart rate startle response (Carson, et al., 2007). Reports have also shown that negative affect (symptoms of depression and anxiety) has been linked to hypertension (Davidson, Jonas, Dixon, & Markovitz, 2000; Raikkonen, Matthews, & Kuller, 2001; Raikkonen, Matthews, Kuller, Reiber, & Bunker, 1999),predict the risk for development of metabolic syndrome in women (Raikkonen, Matthews, & Kuller, 2002), and increases the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (Wassertheil-Smoller, et al., 2004). The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, a study that included 3186 men and 3003 women, found that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was elevated in women with a history of depression, while men with a history of depression were not significantly more likely to have metabolic syndrome (Kinder, Carnethon, Palaniappan, King, & Fortmann, 2004).

The existing literature suggests a significant connection between metabolic disease risk factors and PTSD (Dedert, Calhoun, Watkins, Sherwood, & Beckham, 2010), but mechanisms underlying the relationship of PTSD to metabolic disease risk factors are not well understood. Although few data are available on the influence of race on metabolic disease risk factors in PTSD, there is reason to expect that sociodemographic factors play a role in metabolic disease risk factors. Recent data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey revealed a sex difference in the rates of metabolic disease risk factors by race. While data from men indicated that metabolic syndrome was more prevalent in Caucasians, data from women indicated that metabolic syndrome was more prevalent in African Americans (38.5%), compared to Caucasians (31.5%) (Ervin, 2009). Looking deeper into the pattern of results, several studies have found that African Americans tend to have elevations in several measures of metabolic disease risk, including weight elevations, abdominal obesity, hyperglycemia, and high blood pressure, but that Caucasians exhibit dyslipidemia (e.g. high triglycerides) (Ervin, 2009; Kurella, Lo, & Chertow, 2005; Zeno, et al., 2010). Differences in metabolic disease risk factors across race have lead some to suggest establishing different metabolic disease criteria depending on race (Zeno, et al., 2010).

A study using data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions found that the lifetime prevalence of PTSD in African Americans was 8.7%, in a sample of 34,653 adults (Roberts, Gilman, Breslau, Breslau, & Koenen, 2011). This was significantly higher than what was found both in Caucasians (7.4%) and the general population (7.3%). Higher rates of PTSD in racial minorities could be due in part to differences in trauma severity and access to care. Available research on responses to trauma have found that, while Caucasians report higher rates of trauma, African Americans tend to experience more severe traumatic events for which they are less likely to receive treatment (Kessler, et al., 1995; Perilla, Norris, & Lavizzo, 2002; Roberts, et al., 2011).

Research on the relationship between PTSD and metabolic disease risk factors has suffered from complexity in interpretation due to the high comorbidity of PTSD with MDD and SUD. In addition, while it is clear that sex and race play a role in metabolic disease risk factors, these sociodemographic variables have received little consideration in the relationship between PTSD and metabolic disease risk factors. Thus, the current research has three aims: 1) investigate the associations of PTSD with metabolic disease risk factors among a sample of Caucasian and African American women; 2) explore the role of race in the PTSD and metabolic disease risk factors relationship; and 3) evaluate the associations of psychiatric disorders commonly comorbid with PTSD (current major depressive disorder and history of substance use disorder) and total number of axis I psychiatric disorders with metabolic disease risk factors. Because African Americans have a higher prevalence than Caucasians in obesity, hypertension, and diabetes (Flegal, Carroll, Ogden, & Curtin, 2010; Sumner, 2009),we hypothesized that, relative to Caucasian women, African American women would demonstrate a stronger association between PTSD and the likelihood of metabolic disease risk factors. In addition, since comorbid psychiatric disorders (i.e., MDD, SUD, and number of psychiatric disorders) are also associated with significant medical illness, we hypothesized that measures of physical illness would also be elevated in groups with non-PTSD psychiatric disorders.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

This study employed a secondary analysis of data from an investigation of psychiatric disorders and physical health outcomes in women. Previous publications from this data set have reported on relationships between hostility and ambulatory cardiovascular monitoring (Beckham, et al., 2009)) and intervening effects of psychiatric symptoms in the relationship between childhood trauma and weight outcomes (E. A. Dedert, et al., 2010). Participants were recruited via advertising for a study on trauma and health posted at two local hospitals and a more general flyer to recruit participants for a non-PTSD comparison group. From the 193 participants screened for the study, 11 participants were excluded because they met diagnostic criteria for current alcohol or other substance dependence/abuse or psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia and bipolar with active manic symptoms. Two participants were excluded during the screening process due to medication usage (amitriptyline and methadone). Participants taking second generation antipsychotics were not excluded, but only two participants were taking second generation antipsychotic medications during the study. Although both of these participants were diagnosed with PTSD, one was African American and the other was Caucasian. Due to the low frequency of these medications in our dataset, they likely do not account for the observed results.

Further, 32 participants were recruited for the comparison group but excluded because they met criteria for lifetime (but not current) PTSD or lifetime MDD. Due to an insufficient number of participants in other racial groups to conduct comparisons, the sample was restricted to Caucasians (n = 66) and African Americans (n = 68) for a total sample of 134 women used for analysis. Of the 14 participants who were excluded from analysis five self-identified as having more than one race, four as Asian Americans, three as Hispanic Americans, one as Native American, and one as Pacific Islander.

The study was approved by both the University and VA institutional review boards. Participants were recruited from among outpatients at the Duke University Primary Health Care and PTSD Clinics, and the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and also from the community. Participants provided self-report data on racial/ethnicity status, income, years of education, age, and job status. Participants were excluded if there was a current or previous diagnosis of organic mental disorder, schizophrenia, or paranoid disorders; depression severe enough to require immediate psychiatric treatment (i.e. inpatient psychiatric hospitalization), bipolar depression, or depression accompanied by delusions, hallucinations or bizarre behavior; current SUD (including both alcohol and/or drugs); or illiteracy in English.

We administered the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale to determine PTSD diagnostic status (Blake, et al., 1995), and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997) was used to diagnose other possible Axis I disorders. Current diagnoses were determined using a one-month time frame with the exception of substance abuse in which a three-month time frame was used to define current SUD. Given the high comorbidity of SUD in general and the possible effects on the variables of interest, it was decided that longer period of lack of substance abuse (i.e., greater than the usual one month) was needed. Both of these structured interviews have demonstrated excellent reliability and validity in clinical settings (Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001; Weathers, Ruscio, & Keane, 1999; Zanarini, et al., 2000). Eight diagnostic raters were utilized, and interrater reliability for diagnoses based on videotapes of patient interviews was high (Fleiss’ K = .94). Participants also listed their current medications and provided demographic information, including socioeconomic status based on the Hollingshead index (Hollingshead & Redlich, 1958). Study participants were compensated a total of $150 for two sessions of questionnaires and diagnostic assessment.

Physical Health Measures

Body Mass Index and Abdominal Obesity

Participants provided self-reported height, and study personnel measured weight for calculation of body mass index (BMI), as well as measuring waist circumference (in centimeters) to assess abdominal obesity. Waist circumference was measured once for each participant, so no reliability data were calculated for these measurements. Participants with a BMI score of 30 or more were classified as obese.

Lipid Panel Profiles

Prior to blood draws for lipid assessment, all participants reported fasting for 12 hours. The laboratory technician drew blood into tubes without stasis for the lipid determinations. Serum samples were separated by centrifugation and then analyzed. Lipid assessment consisted of determination of high density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), and plasma triglycerides. Triglycerides were determined enzymatically. HDL assays used a precipitation procedure (Warnick, Benderson, & Albers, 1983). LDL was arithmetically calculated from HDL, total cholesterol, and triglycerides using the Friedewald equation (Friedewald, Levy, & Fredrickson, 1972).

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure was measured with ambulatory blood pressure monitors. Participants were fitted with an ambulatory recorder: the Accutracker II (Suntech Medical Instruments, Raleigh, NC), or the Spacelabs 90207. Participants were instructed to carry on with their usual daily activities, to keep their nondominant arm (where the cuff was attached) at their side whenever the recorder operated, and to wear the monitor for 24 hours. The recorder was programmed to operate every 30 minutes ± 5 minutes during waking hours based on self-reported sleep/wake times. On each measurement occasion, the device obtained single readings systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Both monitors were programmed to retake any blood pressure readings that appeared out of range. Criteria for detection and elimination of final values in the dataset included the following: systolic blood pressure less than 50 mmHg or greater than 245 mmHg; diastolic blood pressure less than 40 mmHg or greater than 140 mmHg; and systolic/diastolic ratio of greater than three. Whenever the systolic or diastolic blood pressure was removed, the corresponding measurement was also removed. Participants rated their level of physical activity each time the recorder operated while they were awake. Analyses for this report used only ratings from inactive periods (e.g., Sitting, Reclining, Sleeping). Each measurement occasion was rated as asleep or awake based on report of sleep and wake times completed during the 24-hour monitoring period.

Statistical Analysis

We tested for demographic differences by current PTSD, current MDD, lifetime SUD, and racial group (Caucasian vs. African Americans) using general linear models for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. To evaluate associations of PTSD with metabolic symptoms, we first split the sample into the following two groups: 1) all participants with PTSD, and 2) all participants without PTSD. Because analysis of a PTSD group with all common comorbidities removed would not be representative of PTSD, we included all participants with PTSD in analyses of the association of PTSD with health variables. However, comorbidity is a critical issue to consider in the association of PTSD with medical problems, so we then evaluated comorbidity by conducting separate analyses comparing presence vs. absence of the following: current PTSD, current MDD, and lifetime SUD. Participants who met criteria for more than one of these disorders were included in more than one analysis, in the interest of accurately representing the psychiatric groups being evaluated. These analyses were conducted using general linear models. A final analysis used regression to evaluate the association of the number of axis I disorders with our dependent measures.

The sample had a mean age of 40.4 (SD = 12.9) and generally resided in the lower middle social class (Hollingshead M = 42.1). As age did not differ between groups, age was not included as a covariate in the models. To examine the relationships of PTSD and race with disease risk factors, we used general linear models to evaluate associations of PTSD and race with triglycerides, BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, HDL, and LDL. We then entered the interaction between PTSD and race. We then conducted similar analyses to evaluate the associations of MDD and race in disease risk factors.

Results

Demographic Differences Across Psychiatric Disorders

Table 1 presents summary statistics for relevant demographic, psychiatric, and medical variables for the PTSD group, the non-PTSD group, and the sample as a whole. Evaluation of age, SES (from Hollingshead categories), and race differences between psychiatric groups revealed no differences between PTSD groups. Participants with current MDD had a higher mean age (F(1,132) = 5.13, p = .025, semipartial η2 = .037) and lower SES (Χ21 = 24.02, p < .001), but no between-group difference in race. Participants with a lifetime SUD had a lower SES (Χ21 = 14.50, p = .006), but no significant differences in age or race. A greater number of Axis I disorders was generally associated with lower SES (F(4,129) = 4.57, p = .002, semipartial η2 = .124), but there was no significant relationship of Axis I disorders with age or race. However, models were not adjusted for SES differences due to problems associated with using covariates to correct for differences in psychiatric groups (Miller & Chapman, 2001).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics and Comparisons by PTSD Status.

| PTSD (n = 63) | Non-PTSD (n = 71) | Total sample (n = 134) | PTSD Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

|

|

||||

| Age | 41.3 (11.6) | 39.6 (14.0) | 40.4 (12.9) | η2 = .004 |

| SES (Hollingshead) | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.2 (1.2) | 42.1 (17.9) | η2 = .046* |

| # of Axis I Disorders | 2.3 (1.1) | 0.7 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.3) | η2 = .390*** |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 33.2 (10.1) | 29.9 (7.8) | 31.4 (9.1) | η2 = .032* |

| Abdominal Obesity (cm) | 97.0 (17.3) | 88.0 (16.9) | 92.2 (17.7) | η2 = .066** |

| High Density Lipoproteins (HDL) | 54.6 (52.1) | 50.5 (12.5) | 52.4 (36.4) | η2 = .003 |

| Low Density Lipoproteins (LDL) | 128.0 (37.7) | 116.2 (35.4) | 121.6 (36.8) | η2 = .026 |

| Triglycerides | 108.6 (68.4) | 89.0 (48.7) | 97.9 (59.1) | η2 = .028 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 123.0 (13.7) | 117.4 (13.5) | 120.1 (13.8) | η2 = .041* |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 73.4 (10.3) | 71.2 (9.4) | 72.2 (9.9) | η2 = .012 |

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | ||

| Major Depressive Disorder | 35 (56%) | 23 (32%) | 58 (43%) | ϕ= .233** |

| Lifetime Substance Use Disorder | 26 (41%) | 12 (17%) | 38 (28%) | ϕ= .270** |

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | 40 (63%) | 27 (38%) | 67 (50%) | ϕ= .254** |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

η2 = semi-partial η2, measure of effect size for general linear models

PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. SES = Socioeconomic status. A higher Hollingshead score indicates lower SES. Due to missing data on one or more of the four components that made up the determination of metabolic syndrome, a total of 12 participants had missing data for the metabolic syndrome variable.

PTSD and Metabolic Disease Risk Factors

Examination of associations between PTSD and metabolic disease risk factors revealed that individuals with PTSD in our sample had higher BMI (F(1,132) = 4.39, p = .038, semipartial η2 = .032) and rate of obesity (F(1,132) = 9.12, p = .003, semipartial η2 = .065), larger abdominal obesity (F(1,131) = 9.28, p = .003, semipartial η2 = .066), and higher systolic blood pressure (F(1,105) = 4.51, p = .036, semipartial η2 = .041).

Race and Metabolic Disease Risk Factors

Table 2 presents summary statistics for demographic, psychiatric, and medical variables by race. Examination of associations between race and metabolic disease risk factors revealed that African American participants had lower SES (F(1,132) = 10.66, p = .001, semipartial η2 = .075), larger abdominal obesity (F(1,131) = 5.81, p = .017, semipartial η2 = .043), and lower triglycerides (F(1,129) = 10.99, p = .001, semipartial η2 = .079).

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics and Comparisons by Race.

| African American (n = 68) | Caucasian (n = 66) | Total sample (n = 134) | Race Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

|

|

||||

| Age | 40.6 (12.9) | 40.1 (13.1) | 40.4 (12.9) | η2 < .001 |

| SES (Hollingshead) | 3.8 (1.0) | 3.1 (1.3) | 42.1 (17.9) | η2 = .075** |

| # of Axis I Disorders | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.3) | η2 < .001 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 32.8 (7.4) | 30.0 (10.4) | 31.4 (9.1) | η2 = .024 |

| Abdominal Obesity (cm) | 95.7 (15.8) | 88.5 (18.9) | 92.2 (17.7) | η2 = .043* |

| High Density Lipoproteins (HDL) | 55.3 (49.5) | 49.3 (11.7) | 52.4 (36.4) | η2 = .007 |

| Low Density Lipoproteins (LDL) | 116.3 (36.0) | 127.2 (37.0) | 121.6 (36.8) | η2 = .022 |

| Triglycerides | 81.8 (47.1) | 114.8 (65.7) | 97.9 (59.1) | η2 = .079** |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 121.7 (15.0) | 118.6 (12.6) | 120.1 (13.8) | η2 = .012 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 73.5 (10.6) | 71.1 (9.1) | 72.2 (9.9) | η2 = .014 |

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | ||

| Major Depressive Disorder | 30 (44%) | 28 (42%) | 58 (43%) | ϕ= .017 |

| Lifetime Substance Use Disorder | 26 (41%) | 12 (17%) | 38 (28%) | ϕ= −.142 |

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | 40 (63%) | 27 (38%) | 67 (50%) | ϕ= .179* |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

η2 = semi-partial η2, measure of effect size for general linear models

PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. SES = Socioeconomic status. A higher Hollingshead score indicates lower SES. Due to missing data on one or more of the four components that made up the determination of metabolic syndrome, a total of 12 participants had missing data for the metabolic syndrome variable.

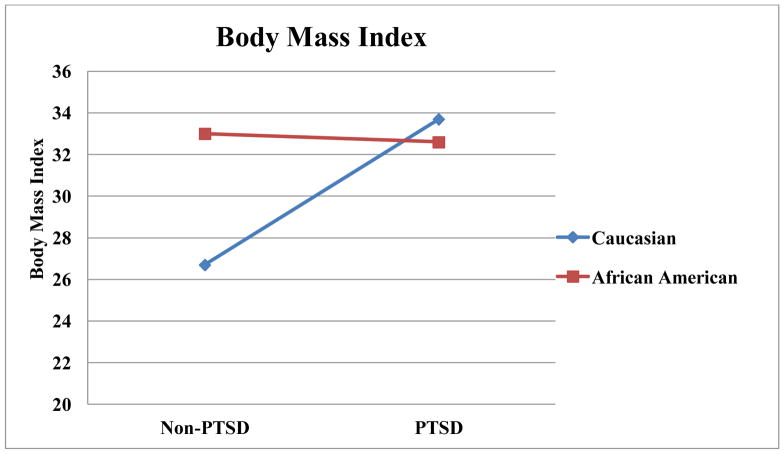

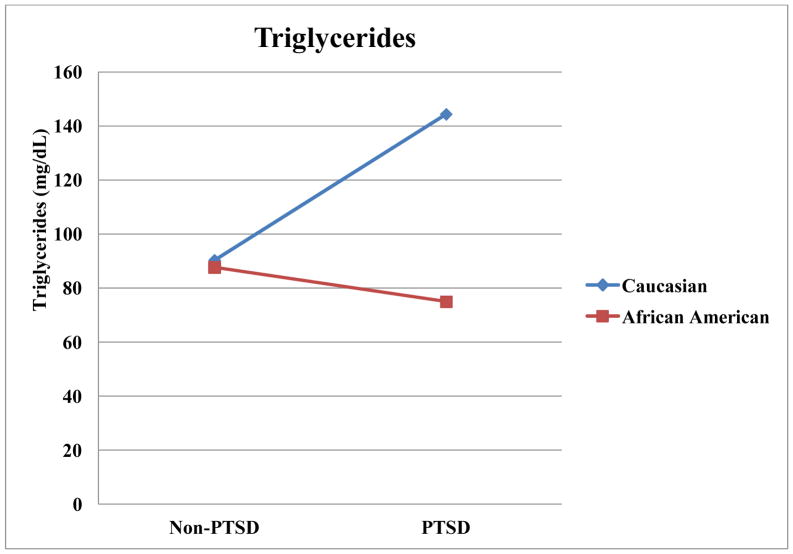

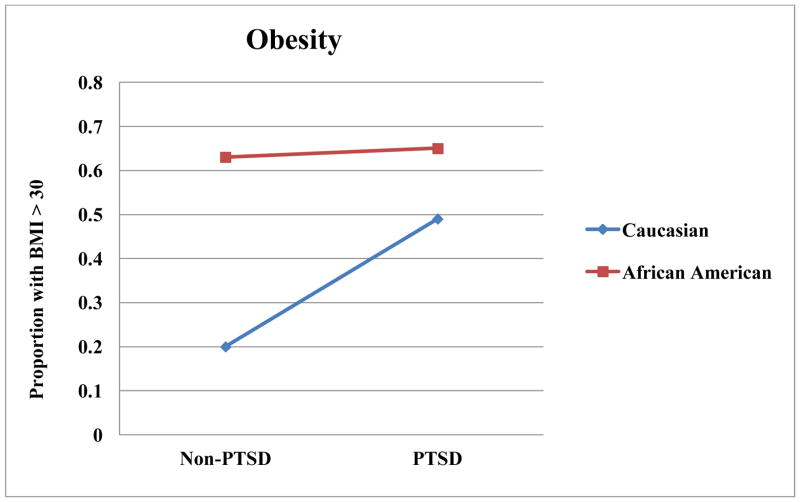

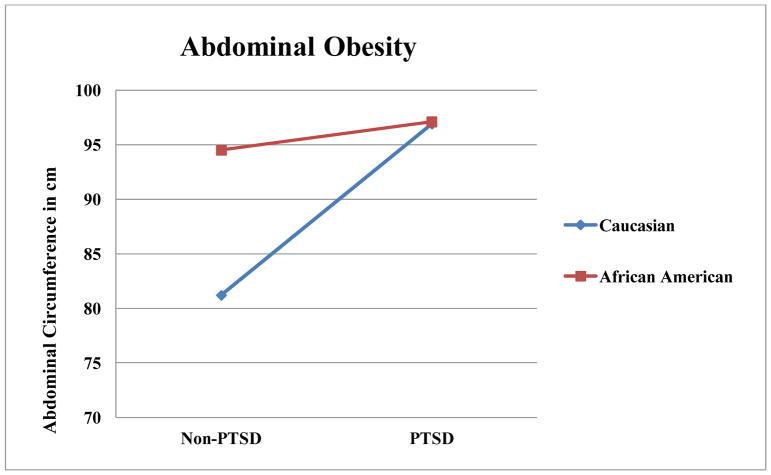

Influences of Race and Comorbidities in PTSD and Metabolic Disease Risk Factors

Results from general linear models examining associations of race and several psychiatric disorders, as well as the interactions of race with these disorders, with dependent variables are summarized in Table 3. As illustrated in Figure 1, there was a race by PTSD interaction in BMI, such that Caucasians without PTSD had a lower BMI than Caucasians with PTSD (t(1) = 3.27, p = .001,d = 4.70). Caucasians without PTSD also had a lower BMI than racial minorities regardless of PTSD status (t(1) = 2.76, p = .007, d = 3.97 for PTSD; t(1)= 3.05, p = .003, d = 4.38 for non-PTSD). Similarly, there was an interaction of PTSD and race on obesity, such that Caucasians without PTSD had lower rates of obesity than each other group (t(1) = 3.82, p < .001, d = 5.49 compared to PTSD Caucasians; t(1) = 3.67, p < .001, d = 5.27 compared to PTSD African Americans; t(1) = 3.17, p = .002, d = 4.54 compared to non-PTSD African Americans). There was an interaction of PTSD and race on abdominal obesity, such that Caucasians without PTSD had lower abdominal obesity than each other group (t(1) = 3.82, p < .001, d = 5.50 compared to PTSD Caucasians; t(1) = 3.93, p < .001, d = 5.64 compared to PTSD African Americans; t(1) = 3.38, p = .001, d = 4.85 compared to non-PTSD African Americans). As illustrated in Figure 2, there was an interaction for triglycerides, such that Caucasians with PTSD had higher triglycerides than each other group (t(1) = 4.00, p < .001, d = 5.76 for non-PTSD Caucasians; t(1) = 4.98, p < .001, d = 7.16 for PTSD African Americans; t(1) = 4.21, p < .001, d = 6.08 for non-PTSD African Americans).

Table 3.

Summary of Models of Race and Psychiatric Disorder Associations with Metabolic Disease Risk Factors.

| Current PTSD | Current MDD | History of Substance Use Disorder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| F | Semipartial η2 | F | Semipartial η2 | F | Semipartial η2 | |

|

|

||||||

| Body Mass Index | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Race | 2.94 | .020 | 2.96 | .020 | 2.78 | .021 |

| Psychiatric D/O | 4.79* | .033 | 16.21*** | .108 | .56 | .004 |

| Race x | 6.10* | .042 | .55 | .004 | .00 | <.001 |

| Psychiatric D/O | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Race | 4.19* | .028 | 4.38* | .029 | 2.64 | .019 |

| Psychiatric D/O | 9.88** | .066 | 16.32*** | .108 | .94 | .007 |

| Race x | 5.26* | .035 | .02 | .000 | .66 | .005 |

| Psychiatric D/O | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Abdominal Obesity (Waist Circumference) | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Race | 5.47* | .036 | 5.51* | .035 | 5.81* | .043 |

| Psychiatric D/O | 10.14** | .067 | 20.00*** | .128 | 1.86 | .014 |

| Race x | 5.19* | .035 | .33 | .002 | .05 | <.001 |

| Psychiatric D/O | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| High Density Lipoproteins | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Race | 1.18 | .009 | .68 | .005 | 2.92 | .022 |

| Psychiatric D/O | .36 | .003 | 2.05 | .016 | 1.77 | .014 |

| Race x | 3.21 | .024 | .81 | .006 | 2.46 | .019 |

| Psychiatric D/O | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Low Density Lipoproteins | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Race | 3.22 | .024 | 3.79 | .027 | 2.39 | .018 |

| Psychiatric D/O | 3.53 | .026 | 7.41** | .054 | .07 | .001 |

| Race x | .44 | .003 | .79 | .006 | .04 | <.001 |

| Psychiatric D/O | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Triglycerides | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Race | 14.48*** | .093 | 12.05** | .078 | 9.62** | .070 |

| Psychiatric D/O | 4.80* | .031 | 14.99*** | .097 | .10 | .001 |

| Race x | 12.45** | .080 | .16 | .001 | .34 | .003 |

| Psychiatric D/O | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Systolic Blood Pressure | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Race | 1.13 | .010 | 1.87 | .017 | 2.88 | .026 |

| Psychiatric D/O | 4.03* | .037 | .99 | .009 | 6.71* | .060 |

| Psychiatric D/O | 1.06 | .010 | 2.85 | .026 | .40 | .004 |

|

|

||||||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Race | 1.44 | .014 | 1.69 | .016 | 3.15 | .029 |

| Psychiatric D/O | 1.22 | .012 | .02 | .000 | 3.29 | .031 |

| Race x | .00 | .000 | .47 | .005 | .90 | .008 |

| Psychiatric D/O | ||||||

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Race by PTSD Interactions for Body Mass Index.

Figure 2.

Race by PTSD Interactions for Triglycerides in milligrams per deciliter.

Models testing the association of MDD and race with disease risk factors revealed that MDD was associated with elevations in BMI, obesity rate, waist-hip ratio, LDL level, and triglyceride level. In contrast to models with PTSD, the models with MDD resulted in no interactions of MDD with race. A history of SUD was associated with higher systolic blood pressure, but no other health risk measures. There were no interactions of SUD history with race in models of health risk measures. The number of total axis I disorders was associated with an increased rate of obesity (F(1,130) = 11.02, p = .001; semipartial η2 = .074), larger waist-hip ratio (F(1,129) = 11.11, p = .001; semipartial η2 = .075), higher LDL levels (F(1,127) = 11.03, p = .001; semipartial η2 = .077), and higher triglyceride levels (F(1,127) = 14.79, p < .001; semipartial η2 = .095).

Discussion

This investigation found that race played significant role in the association of PTSD with metabolic disease. Of the metabolic disease measures that were associated with PTSD, only systolic blood pressure did not also have a significant interaction between PTSD and race. Further, the pattern of interactions was relatively consistent. In our dataset, PTSD did not typically have an impact on metabolic disease risk factors in African Americans, but PTSD was associated with a notable worsening of metabolic disease risk factors in Caucasians. This pattern was noted in BMI, obesity rates, abdominal obesity, and triglycerides.

Across race, results generally indicated that race was not consistently related to metabolic disease risk factors, as African American women had higher rates of obesity, but Caucasian women had higher triglycerides. These findings are consistent with recent epidemiologic data on women (Ervin, 2009).

Because we found no significant increase in rates of obesity, triglyceride levels, waist to hip ratio, or systolic blood pressure in racial minorities with PTSD, it raises the question of whether fasting glucose levels are a key component of increased risk of metabolic syndrome in racial minorities with PTSD, particularly African American women. Our findings are consistent with previous data that suggest that a lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome in racial minorities may be due to lower frequency of problems with triglycerides and HDL levels when compared to Caucasians (Gaillard, Schuster, & Osei, 2009; Osei, 2010) and suggest a stronger relationship between insulin resistance and metabolic risk.

Another important future research question involves the possibility of a ceiling effect for weight problems in racial minorities that prevents further worsening through the presence of PTSD. In contrast, since Caucasian women have a lower rate of obesity, more variance in weight problems is available to be influenced by PTSD.

Further research is needed to determine which mechanisms might lead to especially deleterious effects of PTSD on metabolic disease risk factors in Caucasians. Metabolic abnormalities in PTSD could be influenced by different reactions to atypical anti-psychotic medications. These medications are associated with glucose dysregulation (Jin, Meyer, & Jeste, 2004; Wirshing, et al., 2002) and are often prescribed off-label for treatment of PTSD and might interact with race. Potential psychophysiological mechanisms include differential effects by race on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function, inflammation, immune function, and behavioral health. For example, one study that observed racial differences in metabolic syndrome found that these differences were eliminated when metabolic syndrome criteria included physical fitness, c-reactive protein, percent body fat, and insulin resistance (Zeno, et al., 2010). Research on race differences in physical illness will likely benefit from progress in genetic research. It will be important to consider the influence of race in genetic studies with participants with PTSD. Finally, future research on the influence of race in physical illness would benefit from incorporating cultural variables that provide the potential to explain the process underlying effects of race on physical illness. Cultural elements such as social norms, values, beliefs, and interpersonal styles will need to be examined to provide depth to findings on race effects (Betancourt & Lopez, 1993; Perilla, et al., 2002). This depth will likely provide insights into intervention targets and strategies.

Limitations

Because this is a secondary analysis of an existing data set, data on interesting risk factors such as fasting glucose data and microalbuminuria were not available. As mentioned above, fasting glucose data can be used as criteria for classification of metabolic syndrome (Grundy, Brewer, Cleeman, Smith, & Lenfant, 2004). This is a particularly interesting question for future research in light of previous data indicating that African American women have elevated fasting glucose levels, and higher rates of and mortality from diabetes (Goodwin & Davidson, 2005; Trief, et al., 2006; Weisberg, et al., 2002). However, due to the evolving definition of metabolic syndrome and modified versions used across studies (Zeno, et al., 2010), we believe the current report adds to the literature on metabolic disease risk factors and presents novel data on the role of race in the relationship between PTSD and metabolic disease risk factors. Because our sample was fairly small, these results should be interpreted cautiously. In particular, we explored associations of PTSD with metabolic disease risk factors broadly, with no correction for multiple comparisons. Because this study represents preliminary research into race effects that have not been previously characterized, this exploratory approach is a useful method for research advances. However, it will be important to replicate these results and examine larger, nationally representative data sets that include fasting glucose data before firm conclusions can be reached regarding the role of race in the relationship between PTSD and metabolic disease.

Conclusions

Findings provide additional support for an association of PTSD with metabolic disease that is independent of commonly comorbid disorders that could also influence metabolic disease. In addition, the role of race in the PTSD and health relationship is understudied, especially in light of the findings of the current report. To understand the influence of PTSD on metabolic disease, it is important to analyze and consider the roles of race and culture.

Figure 3.

Race by PTSD Interactions for Obesity Proportions.

Figure 4.

Race by PTSD Interactions for Abdominal Obesity in centimeters.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants who volunteered to participate in this study. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Grants R01MH062482, 2K24DA016388, 1R21CA128965, the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development, Clinical Science, Health Services Research and Development Grant # IIR 08-032, and the Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center. The authors have no competing interests to report. The views expressed in this presentation are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Babic D, Jakovljevic M, Martinac M, Saric M, Topic R, Maslov B. Metabolic syndrome and combat post-traumatic stress disorder intensity: preliminary findings. Psychiatria Danubina. 2007;19(1–2):68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Flood AM, Dennis MF, Calhoun PS. Ambulatory cardiovascular activity and hostility ratings in women with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65(3):268–272. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckham JC, Moore SD, Feldman ME, Hertzberg MA, Kirby AC, Fairbank JA. Health status, somatization, and severity of posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1565–1569. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt H, Lopez SR. The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American Psychologist. 1993;48:629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, et al. The development of a clinician-administered posttraumatic stress disorder scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA. Diseases among men 20 years after exposure to severe stress: Implications for clinical research and medical care. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1997;59:605–614. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199711000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N. The epidemiology of posttraumatic stress disorder: what is the extent of the problem? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 17):16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun PS, Wiley M, Dennis MF, Beckham JC. Self-reported health and physician diagnosed illnesses in women with posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22(2):122–130. doi: 10.1002/jts.20400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DG, Felker BL, Liu CF, Yano EM, Kirchner JE, Chan D, et al. Prevalence of depression-PTSD comorbidity: implications for clinical practice guidelines and primary care-based interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(6):711–718. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0101-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson MA, Metzger LJ, Lasko NB, Paulus LA, Morse AE, Pitman RK, et al. Physiologic reactivity to startling tones in female Vietnam nurse veterans with PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20(5):657–666. doi: 10.1002/jts.20218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David D, Woodward C, Esquenazi J, Mellman TA. Comparison of comorbid physical illnesses among veterans with PTSD and veterans with alcohol dependence. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55(1):82–85. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson K, Jonas BS, Dixon KE, Markovitz JH. Do depression symptoms predict early hypertension incidence in young adults in the CARDIA study? Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(10):1495–1500. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedert EA, Becker ME, Fuemmeler BF, Braxton LE, Calhoun PS, Beckham JC. Childhood traumatic stress and obesity in women: the intervening effects of PTSD and MDD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(6):785–763. doi: 10.1002/jts.20584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedert EA, Calhoun PS, Watkins LL, Sherwood A, Beckham JC. Posttraumatic stress disorder, cardiovascular and metabolic disease: A review of the evidence. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;39(1):61–78. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9165-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis MF, Flood AM, Reynolds V, Araujo G, Clancy CP, Barefoot JC, et al. Evaluation of lifetime trauma exposure and physical health in women with posttraumatic stress disorder or major depressive disorder. Violence Against Women. 2009;15(5):618–627. doi: 10.1177/1077801209331410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobie DJ, Kivlahan DR, Maynard C, Bush KR, Davis TM, Bradley KA. Posttraumatic stress disorder in female veterans: association with self-reported health problems and functional impairment. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164(4):394–400. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton CA. Depression and risk for onset of type II diabetes. A prospective population-based study. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:1097–1102. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervin RB. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adults 20 years of age and over, by sex, age, race and ethnicity, and body mass index: United States, 2003–2006. 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clinical Chemistry. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard T, Schuster D, Osei K. Metabolic Syndrome in Black People of the African Diaspora: The Paradox of Current Classification, Definition and Criteria. Ethnicity & Disease. 2009;19(2):S1–S7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow AM, Tynan D, Schwartz R, Hicks JM, Turek J, Driscol C, et al. Alcohol and drug use in teenagers with diabetes mellitus. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12:11–14. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(91)90033-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Davidson JR. Self-reported diabetes and posttraurnatic stress disorder among adults in the community. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40(5):570–574. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Lenfant C. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433–438. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB, Redlich RL. Social class and mental illness. New York: John Wiley; 1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakovljevic M, Crncevic Z, Ljubicic D, Babic D, Topic R, Saric M. Mental disorders and metabolic syndrome: a fatamorgana or warning reality? Psychiatria Danubina. 2007;19(1–2):76–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakovljevic M, Saric M, Nad S, Topic R, Vuksan-Cusa B. Metabolic syndrome, somatic and psychiatric comorbidity in war veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: Preliminary findings. Psychiatria Danubina. 2006;18(3–4):169–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Meyer JM, Jeste DV. Atypical antipsychotics and glucose dysregulation: a systematic review. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;71(2–3):195–212. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Ciechanowski P. Impact of major depression on chronic medical illness. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:859–863. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinder LS, Carnethon MR, Palaniappan LP, King AC, Fortmann SP. Depression and the metabolic syndrome in young adults: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66(3):316–322. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000124755.91880.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurella M, Lo JC, Chertow GM. Metabolic syndrome and the risk for chronic kidney disease among nondiabetic adults. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2005;16:2134–2140. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Chapman JP. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:40–48. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng RS, Darko DA, Hillson RM. Street drug use among young patients with type 1 diabetes in the UK. Diabetes Medicine. 2004;21:295–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osei K. Metabolic Syndrome in Blacks: Are the Criteria Right? Current Diabetes Reports. 2010;10(3):199–208. doi: 10.1007/s11892-010-0116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perilla JL, Norris FH, Lavizzo EA. Ethnicity, culture, and disaster response: Identifying and explaining ethnic differences in PTSD six months after Hurricane Andrew. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2002;21:20–45. [Google Scholar]

- Perkonigg A, Owashi T, Stein MB, Kirschbaum C, Wittchen HU. Posttraumatic stress disorder and obesity: evidence for a risk association. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikkonen K, Matthews KA, Kuller LH. Trajectory of psychological risk and incident hypertension in middle-aged women. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):798–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikkonen K, Matthews KA, Kuller LH. The relationship between psychological risk attributes and the metabolic syndrome in healthy women: antecedent or consequence? Metabolism. 2002;51(12):1573–1577. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.36301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikkonen K, Matthews KA, Kuller LH, Reiber C, Bunker CH. Anger, hostility, and visceral adipose tissue in healthy postmenopausal women. Metabolism. 1999;48(9):1146–1151. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, Koenen KC. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of posttraumatic stress disorder, and the treatment-seeking for posttraumatic stress disorder in the Unites States. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:71–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Green BL, editors. Understanding relationships among trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and health outcomes. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner AE. Ethnic differences in triglyceride levels and high-density lipoprotein lead to underdiagnosis of the metabolic syndrome in black children and adults. Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;155(3):S7, e7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trief PM, Ouimette P, Wade M, Shanahan P, Weinstock RS. Post-traumatic stress disorder and diabetes: co-morbidity and outcomes in a male veterans sample. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29(5):411–418. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieweg WV, Julius DA, Bates J, Quinn JF, 3rd, Fernandez A, Hasnain M, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder as a risk factor for obesity among male military veterans. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007;116(6):483–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violanti JM, Fekedulegn D, Hartley TA, Andrew ME, Charles LE, Mnatsakanova A, et al. Police trauma and cardiovascular disease: association between PTSD symptoms and metabolic syndrome. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health. 2006;8(4):227–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virmani A, Binienda Z, Ali S, Gaetani F. Links between nutrition, drug abuse, and the metabolic syndrome. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 2006;1074:303–314. doi: 10.1196/annals.1369.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrana SR, Hughes JW, Dennis MF, Calhoun PS, Beckham JC. Effects of posttraumatic stress disorder status and covert hostility on cardiovascular responses to relived anger in women with and without PTSD. Biological Psychology. 2009;82(3):274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnick GR, Benderson J, Albers JJ. Dextran sulfate-Mg+2 precipitation procedure for quantitation of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. In: Cooper GR, editor. Selected methods of clinical chemistry. Vol. 10. Washington, DC: 1983. pp. 91–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassertheil-Smoller S, Shumaker S, Ockene J, Talavera GA, Greenland P, Cochrane B, et al. Depression and cardiovascular sequelae in postmenopausal women. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164(3):289–298. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JR. Clinician-administered PTSD scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression & Anxiety. 2001;13(3):132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1999 Jun;11(2):124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg RB, Bruce SE, Machan JT, Kessler RC, Culpepper L, Keller MB. Nonpsychiatric illness among primary care patients with trauma histories and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(7):848–854. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.7.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirshing DA, Boyd JA, Meng LR, Ballon JS, Marder SR, Wirshing WC. The effects of novel antipsychotics on glucose and lipid levels. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;63(10):856–865. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, et al. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeno SA, Dueuster PA, Davis JL, Kim-Dorner S, Remaley AT, Poth M. Diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome: Caucasians versus African Americans. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders. 2010;8:149–156. doi: 10.1089/met.2009.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]