Abstract

Objective:

Cutaneous drug reactions are the most common type of adverse drug reactions. Adverse cutaneous drug reactions form 2-3% of the hospitalized patients. 2% of these are potentially serious. This study aims to detect the drugs commonly implicated in Steven Johnson Syndrome-Toxic Epidermal Necrosis (SJS-TEN).

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective analysis was done in all patients admitted in the last five years in SDM hospital with the diagnosis of SJS-TEN.

Results:

A total of 22 patients with SJS-TEN were studied. In 11 patients anti-epileptics was the causal drug and in 7, anti-microbials was the causal drug. Recovery was much faster in case of anti epileptics induced SJS-TEN as compared to that induced by ofloxacin.

Conclusion:

SJS-TEN induced by ofloxacin has a higher morbidity and mortality compared to anti convulsants.

KEY WORDS: Anti-epileptics, ofloxacin, Stevens Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrosis

Introduction

Cutaneous drug reactions are the most common type of adverse drug reactions.[1] Adverse cutaneous drug reactions form 2-3% of the hospitalized patients.[2] The percentage of potentially serious reactions is around 2%.[2] Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are potentially serious cutaneous reactions, characterized by high fever, wide-spread blistering exanthema of macules and atypical target-like lesions, accompanied by mucosal involvement.[3,4] In SJS, detachment of the epidermis is less than 10% of the body surface area; the detachment is >30 in TEN.[3] In addition to the severe skin symptoms, both diseases are accompanied by complications in numerous organs, such as the liver, kidney, and lung.[5] Historically, SJS was first described in 1922 by two American physicians named Stevens and Johnson They described an acute mucocutaneous syndrome in two young boys characterized by severe purulent conjunctivitis , severe stomatitis with extensive mucosal necrosis.[3] TEN, also called Lyell's syndrome was first described by the scottish dermatologist Alan Lyell in 1956. He reported four patients with an eruption resembling scalding of the skin objectively and subjectively’, which he called toxic epidermal necrolysis or TEN.[4] Incidence of SJS and TEN is 0.05 to 2 persons per million populations per year.[6,7] Incidence is higher in HIV patients than general population.[8] The reported mortality varies from 3 to 10% for SJS and from 20 to 40% for TEN.[9]

This retrospective study was done to detect the drugs implicated in SJS-TEN in our hospital and their clinical outcome. SJS-TEN is seen to occur among most commonly prescribed drugs. Early identification of the drug will help in prompt withdrawal of the drug thus reducing mortality and morbidity among the patients with SJS TEN. This study aims to create awareness among the treating physicians about the drugs implicated in life threatening reactions to facilitate judicious use of these drugs in future.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis was carried out in all patients admitted in the last five years in SDM hospital with the diagnosis of SJS, TEN. Bastuji's criterion was used to classify the reactions into SJS, TEN and SJS-TEN. We recorded the duration of the rash, drug intake, time period between the drug and reaction, complications, associated comorbidities.

Drug that have been taken within four weeks preceding the onset of symptoms were taken as causal drugs. All patients were treated with barrier nursing with regular monitoring of vitals, fluid and electrolyte balance, strict asepsis and nutrition. Prophylactic antibiotics were given. All patients were given short courses of systemic steroids which were gradually tapered. Institutional ethical committee clearance has been taken for the study.

Results

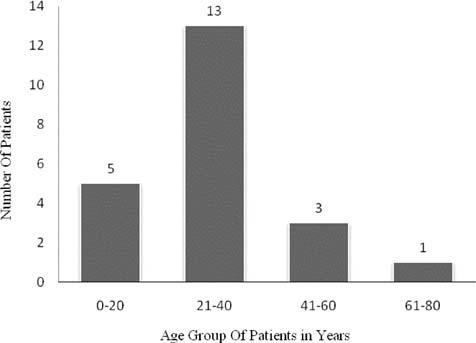

A total of 22 patients were analysed. Of the 22 cases that were scrutinized we found 13 cases of SJS and 9 cases of TEN. Of the 22 cases 14 were men and eight were women. The mean age of the patients was 32.27 years with the youngest being one year old and the oldest 65 years old. 13 of the 22 patients were in the age group of 20-40 years followed by 0-20 years (five patients). [Figure 1] four patients were suffering from HIV, three of who were on antiretroviral therapy and one was diagnosed on admission. 20 patients recovered completely without any major sequelae, one patient died and another was lost to follow up. Of the 20 patients who recovered, two developed symblepheron. In the patient who died, the drug implicated was ofloxacin. Patient presented with seven days history of rashes and fever. She was admitted in Intensive care unit for eight days after which she died of septicaemia. Patient had no history of any systemic illness before the onset of SJS.

Figure 1.

Age distribution of the patients with Steven Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (SJS-TEN)

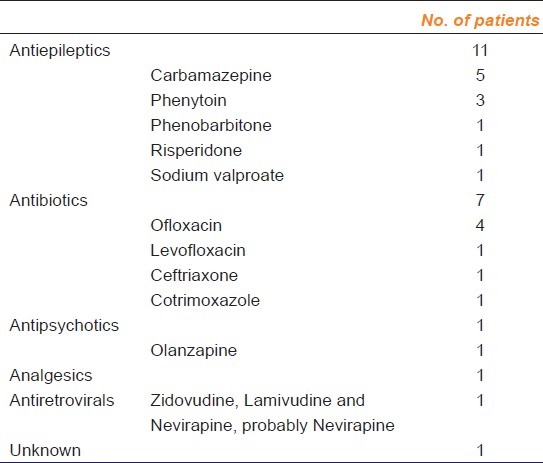

In 50% (11 of 22) of the patients antiepileptics were implicated as the cause of SJS/TEN, followed by antibiotics (7 of 22) [Table 1]. Analgsics, antipsychotics and antiretrovirals were the other offending drugs. The patient who had developed TEN for antiretroviral was on combination therapy with zidovudine, nevirapine and lamivudine. Probably the reaction was due to Nevirapine. In one case the causative drug was unknown. Among the anticonvulsants carbamazepine was responsible for most reactions (27%) followed by phenytoin (13.6%). Ofloxacin was the most common antibiotic causing SJS (18%). One patient developed reaction to sodium valproate which has been rarely reported in literature.

Table 1.

Drugs causing SJS-TEN

Mean time taken for recovery in SJS induced by ofloxacin was 9.6 days whereas carbemazepine and phenytoin took six days and 6.6 days for recovery respectively. None of the patients on antiepileptics died whereas one patient on ofloxacin succumbed.

All patients were given adequate supportive therapy and nursing care. All patients were given systemic steroids for a few days and then tapered. One baby was given IV Immunoglobulins for the treatment and it responded well in five days.

Discussion

In contrast to other studies we noticed a male preponderance (14 males v/s 8 females) with a ratio of 1.75.[1,10,11] This was in agreement with the study done by Barvaliya et al which also reported a male preponderance.[12] Maximum number of patients were in the age group of 20-40 yrs unlike in a study by Roujeau et al[13] where most of the patients were in the 5th decade. Mean age in our study was 32.27 as compared to 25 and 63 in SJS and TEN respectively in a study in Germany[10] In Indian studies like Sharma et al[1] mean age was 22.3. Devi et al[11] observed 68% of the patients were in 20-50 group. Yamane et al[14] reported a mean age of 45.7 yrs.

In our study the most common drugs implicated were antiepileptics (50%) followed by antibiotics (31%). Of the antiepileptics, carbamazepine was the most often implicated drug (27%) followed by phenytoin (13.6%). Carbamazepine was given to the patients mainly for seizure episodes and occasionally for post herpetic neuralgia. Anticonvulsants were the drugs most commonly implicated in SJS-TEN in a six year study conducted on 500 patients in Chandigarh.[15] Kamaliah et al in their report of EM, SJS TEN in North East Malaysia also confirmed that carbamazepine was the most commonly implicated drug in SJS.[16] One of our patients developed reaction to sodium valproate which has been rarely reported in literature and the same has been reported from us.[17]

In contrast to the Indian studies in many of the reports from developed countries antimicrobials were the most common offending drugs.[18–20] In a French survey, NSAIDS were found to be the culprit drugs.[13] Among the antibiotics ofloxacin was most common offending drug (18%) in our study whereas in a study by Yamane et al[14] in Japan the most common offending antibiotics were the cephalosporins. Beta lactams were the most common antibiotics causing SJS-TEN in a study by Wong et al.[20]

18% of patients were HIV positive in our study. Whereas in a study by Barvaliya M,[12] 37.5% of the patient were HIV positive. And in study by European group 7.3% patients had AIDS.[21] In a study by Sharma V,[1] mortality was 26 in SJS and nine in TEN.

In our study, all cases were treated with systemic steroids. Though the role of steroids in treatment of SJS and TEN is controversial, beneficial effect may be there if steroids are started early in treatment with proper dose.[22] IV Immunoglobulin was given in one patient and recovery was seen within five days. We could not make any conclusion about the use of IV Immunoglobulin in treatment of SJS and TEN as it was used only in one patient in our study.

We noticed that recovery time associated with ofloxacin was 9.6 days which was much longer than recovery time with anticonvulsants (six days). No deaths were reported with anticonvulsants while one patient on ofloxacin died. Thus though the adverse reactions with anticonvulsants were more severe, the recovery was much faster than in patients who developed these reactions with antibiotics. Besides, the recovery was uneventful with no major sequelae in case of antiepileptic induced reactions.

Conclusion

Oflaxacin, a commonly used antibiotic in India, has a risk of inducing SJS-TEN, which may be fatal. SJS-TEN induced by ofloxacin has a higher morbidity and mortality compared to anti convulsants. Anti epileptics also have a potential for causing this serious adverse reaction. Since the number of cases studied is less, it warrants further research.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No

References

- 1.Sharma VK, Sethuraman G, Minz A. Stevens Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis and SJS-TEN overlap: A retrospective study of causative drugs and clinical outcome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:238–40. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.41369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma VK, Sethuraman G. Adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs: An overview. J Postgrad Med. 1996;42:15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, Shear NH, Naldi L, Roujeau JC. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyell A. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: An eruption resembling scalding of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1956;68:355–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1956.tb12766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roujeau JC. The spectrum of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: A clinical classification. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:28S–30. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12388434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li LF, Ma C. Epidemiological study of severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions in a city district in China. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:642–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borchers AT, Lee JL, Naguwa SM, Cheema GS, Gershwin ME. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7:598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khambaty MM, Hsu SS. Dermatology of the patient with HIV. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:355–68. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Doval I, LeCleach L, Bocquet H, Otero XL, Roujeau JC. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: Does early withdrawal of causative drugs decreasethe risk of death? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:323–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schopf E, Stuhmer A, Rzany B, Victor N, Zentgraf R, Kapp JF. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: An epidemiologic study from West Germany. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:839–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1991.01680050083008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devi K, George S, Criton S, Suja V, Sridevi PK. Carbamazepine--the commonest cause of toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: A study of 7 years. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:325–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.16782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barvaliya M, Sanmukhani J, Patel T, Paliwal N, Shah H, Tripathi C. Drug-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and SJS-TEN overlap: A multicentric retrospective study. J Postgrad Med. 2011;57:115–9. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.81865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roujeau JC, Guillaume JC, Fabre JP, Penso DP, Fletchet ML, Girre JP. Toxic epidermal necrolysis(Lyells syndrome) Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:37–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.126.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamane Y, Aihara M, Ikezawa Z. Analysis of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in Japan from 2000 to 2006. Allergol Int. 2007;56:419–25. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.O-07-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma VK, Sethuraman G, Kumar B. Cutaneous adverse drug reactions: Clinical pattern and causative agents - a 6 year series from Chandigarh, India. J Postgrad Med. 2001;47:95–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamaliah MD, Zaimal D, Mokhtar N, Nazmi N. Erythema multiforme, Steven Johnson Syndrome, Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in North East Malaysia. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:520–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naveen KN, Arunkumar JS, Hanumanthayya K, Pai VV. Stevens-Johnson syndrome induced by sodium valproate monotherapy. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2012;2:44–5. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.94904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alanko K, Stubb S, Kaupinen K. Cutaneous drug reactions. Clinical types and causative agents. Acts Derm Venerol. 1989;69:223–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kauppinen K, Stubb S. Drug reactions. Causative agents and Clinical types. Acts Derm Venerol. 1984;64:320–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong KC, Kennedy JP, Lee S. Clinical manifestations and outcome in 17 patients of Steven Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:131–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.1999.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fagot JP, Mockenhaupt M, Bouwes-Bavinck JN, Naldi L, Viboud C, Roujeau JC. Nevirapine and the risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. AIDS. 2001;15:1843–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109280-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kardaun SH, Jonkman MF. Dexamethasone pulse therapy for Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:144–8. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]