Abstract

Objective

We aimed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of different cone beam CTs (CBCTs) and the influence of field of view (FOV) in diagnosing simulated periapical lesions.

Methods

6 formalin-fixed lateral mandibular specimens from pigs were used for creating 20 standardized periapical bone defects. 18 roots were selected for the control group. Three CBCT devices [Accuitomo 3D® (Morita, Kyoto, Japan), NewTom 3G (Quantitative Radiology, Verona, Italy) and Scanora® (Soredex, Tuusula, Finland)] and three FOVs (NewTom 3G® FOV 6, 9 and 12 inches) were used to scan the mandible. Five observers assessed the images, using a five-point probability scale for the presence of lesions. Specificity, sensitivity and areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were calculated.

Results

Sensitivity ranged from 72% to 80%. Specificity ranged from 60% to 77%. A difference in scoring between Scanora and the other two devices existed only in the control group. ROC analysis for different FOVs showed a decreased sensitivity with an increasing FOV, but this difference was not significant.

Conclusion

In the control group, there was a difference between the CBCT devices regarding their specificity. FOV size did not show any difference in diagnostic performance. In cases in which conventional radiographic methods in combination with clinical evaluation are not sufficient, CBCT may be the method of choice to assess periapical pathology. CBCT examinations should be complementary to a clinical examination and FOV adaptation can be utilized to keep the dose to the patient as low as possible.

Keywords: cone beam computed tomography, apical lesion, in vitro, sensitivity, field of view

Introduction

Currently, periapical imaging is most frequently used in endodontics in order to establish diagnosis and therapeutic planning, and for perioperative control and monitoring of bone healing.1 The advent and the widespread use of low-dose cone beam CT (CBCT) equipment offers a new perspective in endodontic management, given that it offers more complex spatial information and more details regarding bone structure.1-3 Studies have been carried out that show that CBCT images can detect a higher number of apical lesions than periapical radiographs.4,5 Stravalopulos and Wenzel6 showed that CBCT was superior to periapical radiography in diagnostic accuracy for the detection of artificial periapical lesions prepared in pig jaws. Furthermore, when progression or healing of endodontic lesions needs monitoring, reproducibility of the radiological readings becomes crucial. Standardization of the images facilitates lesion detection and visualization of any changes in the periapical tissues. The latter seems to be more easily achieved with CBCT than with conventional radiological methods.1

Nowadays, many different CBCT systems are used; some of these have limited scan volume capability, to enable capturing only a few teeth. However, an increasing number of CBCT machines present a variable field of view (FOV), to enable capturing the entire maxillofacial skeleton. The radiation dose from dental CBCT is substantially higher than from single intraoral radiography using a photostimulable phosphor plate detector with rectangular collimation. The latter is the conventional method for the follow-up of periapical lesion detection, and its radiation dose lies below 1.5 μSv.7,8 Pauwels et al7 recently showed that the dose range for CBCT has a large variation, depending on the equipment itself and the chosen FOV: a range of 19–44 μSv for a small FOV; 28–268 μSv for a medium FOV and 68–368 μSv for a large FOV.9

In order to select the most appropriate radiological method and scan protocol for periapical lesion detection, it is important to assess the influence of the type of CBCT scan and FOV size on diagnostic accuracy. The aims of this study were (1) to assess the difference between CBCT scanners for the diagnosis of simulated periapical lesions in an animal model, and (2) to establish the influence of FOV size on periapical lesion detection.

Materials and methods

Bone lesion preparation

Three adult pig mandibles with permanent dentition were prepared by formalin fixation after soft tissue removal. Each mandible was sectioned in two parts by removing the chin region, obtaining a total number of six mandibular samples containing the premolar and molar area. All molars and premolars were extracted. 20 teeth without root fractures were obtained and prepared for further periapical visualization.

In the alveolar socket, in the periapical area, a standardized bone lesion was drilled, using an accurate drill machine (Fervi; Veprug, Vignola, Italy). The following sizes were used creating the artificial bone defects: 1 × 1 mm (n = 7), 2 × 2 mm (n = 7) and 3 × 3 mm (n = 6). In each extraction socket, an artificial bone defect was created. This meant a random distribution of the three defect sizes in each of the six mandibular samples. Moreover, as two samples had four extraction sockets, they received an extra defect (1 × 1 mm in the first, 2 × 2 mm in the second). After creating the artificial bone defects, the extracted non-traumatized teeth were repositioned into their alveolar sockets and the mandibles were prepared for CBCT examination by adding a layer of 5 mm of soft tissue simulation (reversible hydrocolloid; Polyflex® Duplicating Material; Dentsply International, Konstanz, Germany). The material had a radio-opacity within the range of the radio-opacity of soft tissue.

CBCT examination

All mandibles were scanned using three different CBCT machines: Accuitomo 3D® (Morita, Kyoto, Japan; 70 kV, 4 mA; pixel size, 0.125 mm), NewTom 3G® (Quantitative Radiology, Verona, Italy; 110 kV, 8 mA; pixel size 0.180 mm) and Scanora® (Soredex, Tuusula, Finland; 85 kV, 8 mA; pixel size 0.133 mm). The specimens were fixed on a polystyrene support in the vertical position and introduced into the CBCT device using the scanner’s medial and lateral light spot for alignment. The position of these specimens within the FOV was checked and adjusted according to the frontal and lateral scout views. In order to compare the difference between CBCTs, the specimens were scanned by all three CBCT devices using an FOV of 6 inches. Furthermore, the mandibular samples were scanned with a medium FOV (9 inches; pixel size 0.25 mm) and a large FOV (12 inches; pixel size 0.33 mm) with the NewTom 3G scanner in order to compare the detection of artificial bone defects using different FOVs.

Evaluation of images

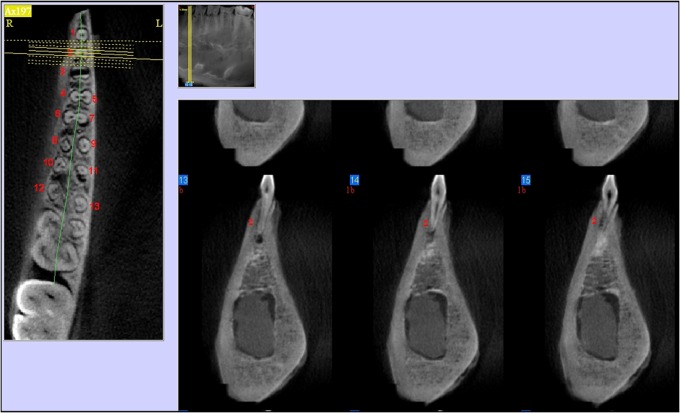

The roots of the premolars and molars included in the study were identified on CBCT images and numbered on the axial slices (Figure 1). In addition, one root per tooth was randomly chosen as the control root (no defect). A total number of 18 roots without fractures and without periapical bone defects underneath served as the control group.

Figure 1.

Cone-beam CT multiplanar view: root identification on axial, panoramic and cross-sectional view

All images were assessed by five examiners with comparable experience in reading CT images. The images were read on a workstation, using the same screen and the default viewer of each CBCT device. A five-point scale was used in the evaluation of the images for the detection of apical cavities: 0, definitely absent; 1, probably absent; 2, uncertain diagnosis; 3, probably present; 4, definitely present.

Statistical analysis

The scores were compared with the gold standard for apical lesions (physical lesion size) using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. This enabled us to determine diagnostic accuracy for each CBCT and FOV used. The specificity and sensitivity were calculated using a cut-off value of more than 2 for the presence of a lesion. The areas under the ROC curve and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for different CBCTs and FOVs were calculated and presented.

The differences in assessment between the CBCTs and FOVs were assessed using the Friedman analysis of variance (ANOVA) test and the post hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Cronbach’s α statistic10 was calculated as a measure of reliability between observers for artificial apical bone defect detection. The response to the five-point probability scale of lesion presence was binarized as follows: 0–2, no lesion; 3–4, lesion. A value greater than 0.7 was considered as a reliable test for this research.11

Statistical analysis was carried out at a significance level of 5% using SPSS® v. 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Differences between CBCTs

Three different CBCT devices were assessed for the detection accuracy of periapical defects. All sensitivity and specificity values are presented in Table 1. The sensitivity ranged from 72% to 80% and the specificity ranged from 60% to 77% using the scores provided by all observers and each CBCT device. The results of the Friedman ANOVA test and its post hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank test are presented in Table 2. Since statistically significant differences were found with the Friedman test [χ2(2) = 20.13; p < 0.001], the post hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed. The differences between Scanora and the other two devices were only significant in the control group (Scanora vs Accuitomo 3D and NewTom 3G; both showed p < 0.001; Table 2).

Table 1. Receiver operating characteristic analysis for lesion detection with different cone beam CT devices. The mean value of the observers is shown.

| Parameter | Accuitomo 3D® | NewTom 3G® | Scanora® |

| Sensitivity (%) | 74 | 72 | 80 |

| Specificity (%) | 61 | 77 | 60 |

| AUC | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| 95% CI for AUC (%) | 0.7–0.8 | 0.7–0.8 | 0.6–0.7 |

AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval.

Accuitomo 3D manufactured by Morita (Kyoto, Japan); NewTom 3G by Quantitative Radiology (Verona, Italy); and Scanora by Soredex (Tuusula, Finland).

Table 2. Friedman analysis of variance test and its post hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank test to determine the difference between cone-beam CT devices in scores for periapical lesion detection.

| Wilcoxon post hoc | All |

Control group |

Experimental group |

|||

| Z | p-value | Z | p - value | Z | p-value | |

| NewTom 3G®—Accuitomo 3D® | −0.02 | 0.98 | −0.53 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.79 |

| Scanora®—Accuitomo 3D | −3.66 | <0.001 | −3.91 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.58 |

| Scanora—NewTom 3G | −3.88 | <0.001 | −3.87 | <0.001 | 2.10 | 0.15 |

Friedman χ2(2) = 20.13 p < 0.001

Accuitomo 3D manufactured by Morita (Kyoto, Japan); NewTom 3G by Quantitative Radiology (Verona, Italy); and Scanora by Soredex (Tuusula, Finland).

Difference between FOVs

As shown in Table 3, the Friedman ANOVA test did not show any statistically significant differences between the diagnostic accuracy for the different FOVs.

Table 3. Accuracy analysis for lesion detection on NewTom 3G® (Quantitative Radiology, Verona, Italy) using different fields of view (FOVs). The mean value of the observers is shown.

| Parameter | FOV 6 inches | FOV 9 inches | FOV 12 inches | p-value Friedman |

| Sensitivity (%) | 84 | 82 | 82 | 0.87 |

| Specificity (%) | 77 | 68 | 66 | 0.23 |

| AUC | 0.889 | 0.830 | 0.820 | 0.17 |

| 95% CI for AUC (%) | 0.8–0.9 | 0.7–0.8 | 0.7–0.8 |

AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval.

Cronbach’s α for interobserver agreement was 0.88.

Discussion

In our study, a variability of sensitivity and specificity for apical lesions was identified between CBCT devices. Sensitivity ranged from 72% to 80%. Specificity ranged from 60% to 77%.

Our results were compared with other references regarding in vivo and in vitro studies on periapical lesion detection. The sensitivity found by Stavropoulos and Wenzel6 in an in vitro study, performed on pig mandibles with spherical apical lesions with diameters of 1 mm and 2 mm, was similar to our results (sensitivity was 54% for the NewTom 3G). Higher values of CBCT sensitivity have been reported in a study on human mandibles by Patel et al,11 who studied ten molars with periapical bone lesions of 2 mm and 4 mm diameter, and found a sensitivity and specificity of 100% for CBCT.

Compared with other results, our in vitro study showed a lower specificity for all three CBCTs used. This poor specificity is an interesting finding. Part of it may have been related to the use of an animal model, which turned out to reveal more anatomical bone holes and a different apical anatomy than the human mandible. The significant difference in scores between CBCTs was observed only for the control group, while no such differences were found in the experimental group. The higher false-positive rates obtained could be due to the lacunae of cancellous bone.

Even if an in vitro study on human mandibles could result in a 100% specificity for the detection of simulated apical lesions with CBCT,12 we believe that for in vivo assessment of CBCT specificity, a valuable gold standard should be identified. In one in vivo study performed in a dog model, De Paula-Silva et al13 considered histological examination as a gold standard for the investigation of the sensitivity and specificity of CBCT for apical lesions on dog teeth. The authors reported a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 100%.

Other studies have investigated the difference in diagnostic accuracy between CBCT and periapical radiographs. Even if this was not the scope of the current study, it is interesting to mention the result of those studies. The majority revealed the superiority of CBCT to periapical radiography in the identification of apical lesions.14-16 Bornstein et al5 demonstrated that 26% of periapical lesions detected on sagittal CBCT scans were not identified on periapical radiographs and that the relationship with the mandibular canal or cortical bone plate could be more accurately assessed using CBCT. Similar results were also obtained by Estrela et al,14 who found a sensitivity of 100% for CBCT in lesion detection and a much lower sensitivity of panoramic (28%) and periapical (55%) radiographs. Christiansen et al17 found a considerable variation between the observers’ detection of a remaining defect on periapical radiographs and CBCT images. A year later, after performing periapical surgery, they found more remaining defects using CBCT images, but the authors concluded that it is uncertain how this information is related to success or failure after root-end resection. The literature results regarding the incidence of false-positive results for in vivo CBCT assessment of apical lesions remain contradictory because of the difficulty of finding a valuable gold standard for in vivo studies. Only with a valuable gold standard can the clinical relevance of these studies be proven: does the difference in lesion detection influence treatment choice and/or success? The FOV size scan could also influence the diagnostic accuracy of CBCT for different types of lesion assessment. Kamburoglu and Kursun18 showed in an in vitro study that the ultra- and high-resolution of two different CBCTs [ILUMA® CBCT Scanner (IMTEC Imaging LLC, Ardmore, OK) and 3D Accuitomo® (Morita)] have better diagnostic accuracy than low-resolution images in the detection of a 0.5 mm diameter of simulated internal root resorption cavities. Haiter-Neto et al19 compared diagnostic accuracy for caries detection of two different CBCT systems [NewTom 3G and 3DX Accuitomo® (Morita)] and FOVs: 6, 9 and 12 inches. The results show that the sensitivity and specificity for caries diagnosis is significantly influenced by the type of CBCT and FOV.

Our study demonstrated no significant differences for apical lesion detection using different FOVs.

In conclusion, we have found a difference between CBCT devices in periapical lesion detection. However, this difference was significant only for the control group, where more false-positive diagnoses occurred. FOV size did not show any difference in diagnostic performance. Although the results of an in vitro study using an animal model cannot be considered the best reference for clinical situations, we can draw the conclusion that, if CBCT examination is chosen as the tool for periapical lesion diagnosis, an adaptation of the FOV to obtain the lowest radiation dose to the patient should always be considered. Moreover, owing to the occurrence of false-positive results, a CBCT examination should be complementary to a clinical examination in order to establish a correct diagnosis and suitable treatment strategy.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Sorana Bolboaca and Oana Almăşan, Faculty of Dentistry, Iuliu Haţieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, who provided statistical analysis and medical writing assistance for the manuscript.

Footnotes

This study was performed within the SEDENTEXCT project of the European Atomic Energy Community's Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007–2011 under grant agreement no. 212246.

References

- 1.Patel S, Dawood A, Whaites E, Pitt Ford T. New dimensions in endodontic imaging: part 1. Conventional and alternative radiographic systems. Int Endod J 2009;42:447–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel S. New dimensions in endodontic imaging: part 2. Cone beam computed tomography. Int Endod J 2009;42:463–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Assche N, Jacobs R, Coucke W, van Steenberghe D, Quirynen M. Radiographic detection of artificial intra-bony defects in the edentulous area. Clin Oral Implants Res 2009;20:273–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lofthang-Hansen S, Huumonen S, Grondahl K. Limited cone beam computed tomography and intra-oral radiography for the diagnosis of periapical pathology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007;103:114–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bornstein MM, Lauber R, Sendi P, von Arx T. Comparison of periapical radiography and limited cone beam computed tomography in mandibular molars for analysis of anatomical landmarks before apical surgery. J Endod 2011;37:151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stavropoulos A, Wenzel A. Accuracy of cone beam dental CT, intraoral digital and conventional film radiography for the detection of periapical lesions. An ex vivo study in pig jaws. Clin Oral Investig 2007;11:101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pauwels R, Beinsberger J, Collaert B, Theodorakou C, Rogers J, Walker A, et al. The SEDENTEXCT Project Consortium. Effective dose range for dental cone beam computed tomography scanners. Eur J Radiol 2012;81:267–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludlow JB, Davies-Ludlow LE, White SC. Patient risk related to common dental radiographic examinations: the impact of 2007 International Commission on Radiological Protection recommendations regarding dose calculation. J Am Dent Assoc 2008;139:1237–1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loubele M, Jacobs R, Maes F, Denis K, White S, Coudyzer W, et al. Image quality vs radiation dose of four cone beam computed tomography scanners. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2008;37:309–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951;16:297–334 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ 1997;314:572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel S, Dawood A, Mannocci F, Wilson R, Pitt Ford T. Detection of periapical bone defects in human jaws using cone beam computed tomography and intraoral radiography. Int Endod J 2009;42:507–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Paula-Silva FW, Wu M, Leonardo MR, da Silva LA, Wesselink PR. Accuracy of apical radiography and cone beam computed tomography scans in diagnosing apical periodontitis using histopathological findings as gold standard. J Endod 2009;35:1009–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estrela C, Bueno MR, Leles CR, Azevedo B, Azevedo JR. Accuracy of cone beam computed tomography and panoramic and periapical radiography for detection of apical periodontitis. J Endod 2008;34:273–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estrela C, Bueno MR, Azevedo BC, Azevedo JR, Pécora JD. A new periapical index based on cone beam computed tomography. J Endod 2008;34:1325–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moura MS, Guedes OA, De Alencar AH, Azevedo BC, Esterela C.Influence of length of root canal obturation on apical peridontitis detected by periapical radiography and cone beam computed tomography. J Endod 2009;35:805–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christiansen R, Kirkevang LL, Gotfredsen E, Wenzel A. Periapical radiography and cone beam computed tomography for assessment of the periapical bone defect 1 week and 12 months after root-end resection. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol 2009;38:531–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamburoglu K, Kursun S. A comparison of diagnostic accuracy of CBCT images of different voxel resolutions to detect simulated small internal resorption cavities. Int Endod J 2010;43:798–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haiter-Neto F, Wenzel A, Gotfredsen E. Diagnostic accuracy of cone beam computed tomography scans compared with intraoral image modalities for detection of caries lesions. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2008;37:18–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]