Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) was discovered more than two decades ago, but progress towards a vaccine has been slow. HCV infection will spontaneously clear in about 25% of people. Studies of spontaneous HCV clearance in chimpanzees and human beings have identified host and viral factors that could be important in the control of HCV infection and the design of HCV vaccines. Although data from studies of chimpanzees suggest that protection against reinfection is possible after spontaneous clearance, HCV is a human disease. Results from studies of reinfection risk after spontaneous clearance in injecting drug users are conflicting, but some people seem to have protection against HCV persistence. To guide future vaccine development, we assess data from studies of HCV reinfection after spontaneous clearance, discuss flaws in the methods of previous human studies, and suggest essential components for future investigations of control of HCV infection.

Introduction

Two decades have passed since the discovery of hepatitis C virus (HCV),1 and although understanding of the virus has greatly increased and major advances in therapeutic development have been made, no effective vaccine exists to prevent new infections. Spontaneous viral clearance occurs in about 25% of individuals, generally in the first 6 months of infection.2 Researchers are interested in whether spontaneous viral clearance (host immune-mediated clearance) confers protection against reinfection, particularly against reinfection followed by viral persistence.

Studies of chimpanzees3–8 and human beings9,10 have shown that, after HCV reinfection, control of viral replication is better, duration of infection is shorter, and the likelihood of viral clearance is higher than in primary infection. These findings suggest that previous clearance of an HCV infection could provide some protection against persistent reinfection. In chimpanzees, rapid virological control after reinfection is associated with HCV-specific T-cell responses.5,7,8 Cohort studies of injecting drug users (IDUs)10–19 have assessed whether previous spontaneous HCV clearance provides protection against HCV reinfection, with inconsistent results. Immunological correlates of improved clearance after reinfection might identify potential targets for vaccine development.20

Acute HCV infection and clearance

HCV virus is present in blood 2–14 days after initial exposure. Concentrations of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase increase and HCV-specific antibodies are produced 20–150 days after exposure.21–23 Primary infection with HCV is generally asymptomatic, although 15–30% of individuals develop symptomatic acute hepatitis illness within 5–12 weeks of exposure lasting 2–12 weeks.24,25 Symptomatic primary HCV infection is often mild, with non-specific symptoms such as lethargy and myalgia, but individuals can present with jaundice.24,25 In about 25% of patients, acute infection is followed by viral clearance, defined as undetectable concentrations of HCV RNA in blood.2 Most of these individuals clear infection by 6 months (73–86%) or 12 months (87–95%).26–28 However, spontaneous HCV clearance after 1 year has been reported.29,30 Most patients do not have viral clearance and viraemia persists after 6 months, leading to chronic infection and progression to cirrhosis in 5–10% of individuals within 20 years.31

Whether HCV infection spontaneously clears or persists is affected by a complex set of interactions between virus and host that is only partly understood. Host factors such as female sex,2,18,32 initial immune response,33–37 virus-specific neutralising antibodies,38,39 and host genetics40–42 have been associated with clearance in prospective studies of acute HCV infection. Pathogen-associated factors, such as diversity of HCV viral quasispecies43,44 and HCV genotype,45 might also be linked with clearance. In large cross-sectional studies of people infected with HCV for an unknown period, viral clearance is associated with several factors: female sex,2,46,47 young age,48,49 indigenous Canadian ethnic origin,46 non-black ethnic origin,50–52 absence of alcohol-use disorder,53 no tobacco use,50 HIV-negative status,46–48,51,53 and chronic hepatitis B infection.47,48,50,52,54,55 However, these cross-sectional studies of individuals who tested positive on tests for HCV antibodies—ie, have been exposed to the virus at some point—are subject to selection bias, in view of the potential for HCV reinfection in people with initial spontaneous clearance during long-term follow-up.

Host polymorphisms of proteins such as HLA class I and II, natural-killer-cell receptors, chemokines, interleukins, and of interferon-stimulated genes have been associated with control of HCV.40 However, the genetic associations identified have not been confirmed in independent cohorts, differ in diverse populations, and studies are limited by small sample size or varying definitions of HCV outcome; moreover, little is known about their functional basis.40

Perhaps the strongest genetic association with HCV clearance is with IL28B.41,42,56,57 This gene encodes interferon-λ 3, which is involved in viral control.58 www.thelancet.com/infection Individuals with unfavourable IL28B genotypes are less likely to clear HCV infection than are those with favourable alleles.41,42,56,57 This association is independent of both sex and symptomatic HCV infection with jaundice.42 Although the mechanism by which interferon- λ 3 acts during HCV infection is unknown, this cytokine has direct antiviral actions in vivo and readily inhibits HCV replication in hepatoma cells.58

A strong host immune response (innate and adaptive) is important for spontaneous HCV clearance.33–36 During acute infection, HCV persistence can occur through evasion of the innate immune response.37 HCV could partly or completely counter the innate immune response by disrupting cellular signalling pathways that lead to interferon synthesis, and by subverting cellular signalling to restrict expression of interferon-stimulated genes and block their antiviral effcts.37 The response of interferon-stimulated genes seems to be important since findings from chimpanzee studies suggest that their expression in the liver during acute HCV correlates with spontaneous clearance.59

Available evidence indicates that individuals with primary infections that later clear have strong, broadly specific, and sustained adaptive cellular immune responses, whereas many of those who develop persistent infection have weak cellular immune responses that do not last.38,39 Strong cellular immune responses have also been noted in high-risk individuals who do not have HCV antibodies, suggesting that clearance can occur rapidly, before antibodies are produced.60,61

Virus-specific neutralising antibodies can drive sequence evolution and might affect the outcome of infection62 and protection against reinfection.10 The best available assay systems for HCV neutralising antibodies use virus-like particles or envelope sequences incorporated within pseudotyped viruses that maintain the native configuration of the HCV envelope glyco-proteins. Initial studies with this method showed that neutralising antibodies were rare in individuals who went on to resolve infection,63–65 although this finding was not universally reported.66 However, a longitudinal study with homologous viral pseudoparticles showed that clearance of infection was associated with rapid development of neutralising antibodies.67

HCV reinfection

Occurrence

Studies of HCV reinfection provide insight into factors important for protection against persistent infection, which is a central issue for vaccine design. However, study of HCV reinfection in people has been difficult. Studies in chimpanzees have generated the most robust data on HCV reinfection because experiments can be carefully designed to study re-exposure and reinfection. Despite apparently efficient immune responses in primary infection resulting in viral clearance, reinfection can occur in chimpanzees with both homologous and heterologous viruses.68,69 However, reinfection episodes have been linked with improved control of viral replication, a short course of infection, and an increased likelihood of viral clearance compared with primary infection.3–8 Rapid virological control after chimpanzees are reinfected is connected to HCV-specific T-cell responses.5,7,8 When CD4 T cells are depleted in vivo before reinfection, persistent HCV infection ensues.70 Similarly, depletion of CD8 T cells extended HCV viraemia, which was controlled only when this subset of cells recovered in the liver.8 In this context, cross-genotype immunity has been recorded,6 but viral persistence seems more likely in the setting of heterologous reinfection.7

Nevertheless, HCV is a uniquely human disease, and investigations of HCV reinfection in people have improved understanding of protective immunity. In an early case series,71 reinfection was recorded in five children with thalassaemia that were re-exposed to HCV after spontaneous clearance. Reinfection has also been reported in case studies of IDUs9,12,13,17,28,72–75 and men who have sex with men.76 Several observational cohort studies of IDUs with continuing risk behaviours for HCV acquisition have been done, assessing HCV reinfection after spontaneous clearance (tables 1, 2).10,12–19,77 Collectively, these studies of IDUs are valuable because they give a human model for protection against HCV infection. Specifically, these investigations enable measurement of the incidence of HCV reinfection (and how it compares with incidence of primary HCV infection), the proportion who develop persistent HCV reinfection (and hence incidence of persistent infection), and the natural history of HCV reinfection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of injecting drug users assessed for HCV infection and reinfection in longitudinal studies

| Country | Cohort design | HCV virological assessments | Study period | Study populations | Age (years) | Men | Ethnic origin | Infected with HIV at baseline | Injection drug use at baseline | Frequent injecting* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mehta12 | USA | Prospective | Retrospective | 1988–95 | Not infected (n=164) vs HCV clearance (n=98) | 32 (7·0) vs 41 (6·3) | 121 (74%) vs 58 (59%) | African-American: 146 (90%) vs 87 (90%) | 17 (10%) vs 36 (37%) | 129 (79%) vs 64 (65%) | 35 (21%) vs 32 (33%) |

| Grebely13 | Canada | Retrospective | Retrospective | 1992–2005 | Not infected (n=926) vs HCV clearance (n=152) | 44 (3·3) vs 41 (11·3) | 628 (67%) vs 93 (61%) | White: 541 (58%) vs 69 (45%) | 68 (7%) vs 35 (23%) | 241 (26%) vs 73 (48%) | 129 (14%) vs 38 (25%) |

| Micallef14 | Australia | Retrospective | Retrospective | 1993–2002 | Not infected (n=423) vs HCV clearance (n=18) | 23 (15–54)† vs 23 (16–32)† | 166 (39%) vs 7 (39%) | NA | NA | NA | 61% vs 56%‡ |

| Aitken15 | Australia | Prospective | Prospective | 2005–07 | Not infected (n=55) vs HCV clearance (n=50) | 25 vs 27 | 19 (35%) vs 22 (44%) | White: 37 (74%) vs 45 (82%) | 0 (0%) vs 0 (0%) | 55 (100%) vs 50 (100%) | 29 (58%) vs 20 (36%) |

| van de Laar17 | Netherlands | Prospective | Retrospective | 1985–2005 | Not infected (n=168)§ vs HCV clearance (n=24) | 29 vs 27 | 112 (67%) vs 9 (38%) | Western European: 139 (83%) vs | 4 (2%) vs 2 (8%) | 100 (60%) vs 23 (96%) | 26 (16%) vs 12 (50%) |

| Page18 | USA | Prospective | Prospective | 2000–08 | Not infected (n=380) vs HCV clearance (n=22) | 23 vs 22 | 253 (67%) vs 10 (46%) | White: 290 (77%) vs 16 (73%) | 6 (2%) vs 0 (0%) | 380 (100%) vs 22 (100%) | 122 (33%) vs 4 (24%) |

| Osburn10 | USA | Prospective | Prospective | 1997–2008 | Not infected (n=179) vs HCV clearance (n=22) | 23 vs 25 | 80 (45%) vs 10 (45%) | White: 134 (75%) vs 22 (100%) | NA vs 1 (4%) | NA vs 22 (100%) | NA |

| Dove77 | USA | Prospective | Prospective | NA | HCV clearance (n=6) | 46 (37–70)† | 4 (67%) | African-American: 2 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (100%) |

| Currie16 | USA | Prospective | Prospective | 1997–2001 | HCV clearance (n=29) | 47 (7·5) | 16 (55%) | African-American: 7 (24%) | 12 (41%) | 17 (59%) | NA |

| Grebely19 | Australia | Prospective | Prospective | 2004–07 | HCV clearance (n=30) | 33 | 20 (67%) | White: 28 (93%) | 7 (23%) | 5 (17%) | 2 (7%) |

Data are n (%) or mean (SD when available), unless otherwise stated. Percentages taken directly from relevant reports. HCV=hepatitis C virus. NA=not available.

Frequent use is classed as use more than once every day at the baseline visit.

Median (range).

Data taken from Dore and Micallef.78

Data taken from van den Berg et al.79

Data taken from Cox et al.22

Table 2.

Infection and reinfection in injecting drug users in longitudinal studies

| Study populations | Number of new infections during follow-up | Median follow-up (years) | Incidence rate per 100 person- years | Crude incidence rate ratio | Adjusted ratio (95% CI) | p value | Median HCV RNA testing interval for patients previously infected (months)* | Clearance of reinfection in patients whose infection had previously cleared† | Reinfection in prevalent or incident cases? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mehta12 | Not infected (n=164) vs HCV clearance (n=98) | 35 vs 12 | 2·4 vs 2·1 | 8·6 vs 5·4 | 0·63 | 0·45 (0·23–0·88)† | 0·02 | 6·3 (6) | 6 of 9 (67%)‡ | Prevalent |

| Grebely13 | Not infected (n=926) vs HCV clearance (n=152) | 172 vs 14 | 2·8 vs 5·2 | 8·1 vs 1·8 | 0·22 | 0·23 (0·10–0·51)§ | <0·001 | 15·6 | 4 of 14 (29%) | Prevalent |

| Micallef14 | Not infected (n=423) vs HCV clearance (n=18) | 114 vs 13 | 1·0 vs 1·2 | 17·0 vs 42·0 | 2·47 | 1·1¶ | 0·80 | 5·0 (6) | 3 of 7 (43%) | Incident |

| Aitken15 | Not infected (n=55) vs HCV clearance (n=50) | 10 vs 23 | NA | 15·5 vs 46·8 | 3·02 | 2·54 (1·11–5·78)‡ | 0·027 | 3·8 (3) | 9 of 22 (41%) | Prevalent and incident |

| van de Laar17 | Not infected (n=168)|| vs HCV clearance (n=24) | 58 vs 9 | 3·6 vs 10·5 | 6·7 vs 9·9 | 1·5 | NA | NA | 7·3 (4–6) | 3 of 9 (33%) | Incident |

| Page18 | Not infected (n=380) vs HCV clearance (n=27) | 132 vs 7 | NA | 26·7 vs 24·6 | 0·92 | NA | NA | 3·0 (3) | 7 of 7 (100%) | Incident |

| Osburn10 | Not infected (n=179)** vs HCV clearance (n=22) | 62 vs 11 | NA | 27·2 vs 30·1 | 1·11 | NA | NA | 1·0 vs 1·0 (1) | 10 of 12 (83%) | Incident |

| Currie16 | HCV clearance (n=29) | 0 | 5·5 | 0·0 | NA | NA | NA | NA (6) | 0 of 29 | Prevalent |

| Grebely19 | HCV clearance (n=30) | 2 | 1·1 | 6·1 | NA | NA | NA | 3·0 (3) | 2 of 2 (100%) | Incident |

Similar rates of primary infection and reinfection after adjustment for potential differences in risk behaviour would suggest that previous clearance of HCV infection does not provide sterilising immunity against reinfection. However, the proportion of persistent HCV reinfections should be measured. For example, if most reinfections spontaneously cleared, there would be a strong argument for some level of protection. Measurement of the size and duration of HCV viraemia during reinfection as compared with primary infection helps to establish whether protection is genetic or immunological. A reduction in the degree or duration of viraemia would suggest that acquired protective immunity has a role, because fixed genetic factors would not adapt and become more efficient as does the immune response. Studies of HCV reinfection in IDUs (tables 1, 2) further understanding of all three parameters and have implications for HCV vaccines.

Researchers in Baltimore (MD, USA) investigated whether previous clearance reduces the risk of HCV reinfection in a cohort study.12 After adjustment for risk behaviour, individuals with previous HCV clearance were half as likely to be infected during follow-up as were those who had not been infected previously (table 2).12 Further data supporting these findings came from a prospective cohort of IDUs in Vancouver (BC, Canada).13 Importantly, the median time between HCV RNA testing was long in both studies (table 2).13

Data from other cohorts, however, suggest that previous spontaneous clearance of HCV infection might not reduce risk of new infection.10,14,15,17,18 A retrospective cohort study of young, high-risk IDUs from Sydney (NSW, Australia)14—with more frequent testing than in the other studies12,13—showed no difference between incidence of HCV infection in individuals with no previous infection and in those with previous HCV clearance (table 2). A prospective cohort study in Melbourne (VIC, Australia),15 also showed high reinfection rates in IDUs who had previously cleared HCV infection (table 2). Previously infected IDUs with HCV clearance were 2·5 times more likely to become infected than were those who had not been previously infected. Similar findings have been reported in the USA.10,18 Frequent monitoring of HCV infection status in a study of young IDUs from Baltimore10 showed infection rates of individuals who had no previous infection and of those with previous clearance were similar (table 2).

In the Netherlands, van de Laar and colleagues17 noted that HCV reinfection was at least as common as initial infection in their cohort (table 2). Although testing intervals for HCV reinfection were long, they recorded a decline in the incidence of HCV reinfection from 20·4 per 100 person-years in 1985–1995, to 4·2 per 100 person-years in 1995–2005. Incidence of initial HCV infection fell from 27·5 per 100 person-years in the late 1980s to roughly 2·0 per 100 person-years in 2005. Collectively, these cohort studies suggest that rates of infection and reinfection are similar when short testing intervals are used. Thus, HCV infection in people does not confer sterilising immunity.

Clearance of reinfection

Although reinfection is common, it does not always lead to persistent infection. Spontaneous clearance of HCV reinfection has been frequently recorded (table 2); data suggest that some individuals can clear HCV after one exposure more efficiently than can others. Overall, clearance of the reinfection strain is fairly common, with some individuals able to spontaneously clear HCV with different genotypes from that of the initial infection.10,14,15,18

A high rate of clearance of HCV reinfection is not surprising, because, by definition, individuals at risk have had clearance of primary infection, and host characteristics are associated with clearance. Furthermore, it does not indicate that previous HCV infection with clearance changes the course of reinfection. Rates of clearance after reinfection are probably underestimated in most studies, because HCV RNA testing intervals longer than 1 month could cause many cases of clearance to be missed, and will therefore be biased to detection of HCV reinfections with viral persistence.80 Furthermore, longitudinal follow-up of HCV reinfection cases with long intervals between tests will mean clearance cases are misclassified as persistent cases. As such, caution must be used in interpretation of results of studies with long intervals between tests or short follow-up time.

Natural history of reinfection

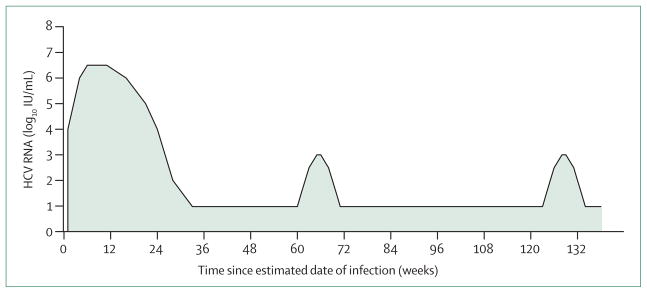

As recorded in chimpanzees, evidence indicates that HCV RNA concentrations after reinfection in people are lower, generally more transient, and shorter in duration than during initial infection.10 In a longitudinal study of IDUs,10 median duration of HCV viraemia was four times longer during initial infection than during reinfection (232 days vs 77 days) and peak median log HCV RNA concentration was lower (3·1 log IU/mL vs 6·7 log IU/mL),10 suggesting people develop adaptive protective immunity (figure).

Figure. HCV infection, clearance, and reinfection.

HCV reinfection events after spontaneous clearance have lower HCV RNA concentrations and shorter infection durations than initial HCV infection. HCV=hepatitis C virus.

The emergence of a new dominant virus during chronic infection (without a period free of viraemia) does not elicit an increased number of new HCV-specific T-cell responses,10 potentially because of virus-induced immune tolerance or exhaustion.81,82 By contrast, different responses of HCV-specific T cells during reinfection have been documented.10 Additionally, a response of neutralising anti bodies to heterologous HCV pseudo-particles was noted in 60% of reinfected IDUs. Although neutralising antibodies do not generally neutralise heterologous HCV pseudoparticles during the acute phase of infections that progress to chronicity,62,64 their presence in reinfected individuals was independent of the sequence divergence between the stimulating virus and the test HCV pseudo particle sequence.10 These data suggest that reinfection is associated with the generation of cross-reactive neutralising antibodies.

However, Osburn and colleagues10 detected new HCV-specific T-cell responses and cross-reactive neutralising antibodies in reinfected individuals who did not clear reinfection. Therefore, although improved cellular and humoral immune responses play a part in control of reinfection, they are probably not sufficient for protection against HCV reinfection with persistence in all cases. Further longitudinal investigation of adaptive immunity during primary infection and reinfection is necessary for reliable identification of the characteristics of protective immunity associated with repeated clearance of HCV infection and hence for future vaccine research.

Study limitations

The substantial heterogeneity of studies of HCV reinfection in people has an important effect on interpretation, particularly on cross-study comparison. Apart from differences in study design (eg, follow-up of cohorts with previous infection and clearance vs cohorts with incident infection and subsequent reinfection) and statistical analyses, clear variation in age, sex, ethnic origin, injecting risk behaviours, and presence of viral co-infections between the cohorts exists (table 1). Risk behaviours of individuals with no previous infection and of those who have cleared an infection might differ and change over time; hence, an analysis without adjustment for time-updated risk behaviour as a proxy for re-exposure to HCV might have misleading findings.78 Risk behaviour information needs to be collected accurately and regularly.

Definitions of viral clearance and reinfection vary between studies, as do the testing intervals and HCV RNA assays (table 2). The type of assay used is important because HCV seroconversion reliably allows detection of almost all initial infections, but HCV reinfection necessitates detection of HCV RNA. Mathematical modelling has shown that studies with long HCV RNA testing intervals underestimate the incidence of HCV reinfection and probability of spontaneous HCV clearance after reinfection.83

Future studies

Investigations into spontaneous HCV clearance of infection and reinfection and into correlates of protection could provide crucial insights into HCV vaccine design. Understanding of host factors essential for control of HCV—particularly after several exposure events—will provide important information about the development of components necessary for future vaccines. Because present results in people are inconclusive, further investigation into possible protective immunity is needed.

The ideal study to improve understanding of primary HCV infection and reinfection, with a specific focus on potential development of an HCV vaccine that would provide protection against viral persistence, would be designed in a specific way. Uninfected, high-risk individuals would be recruited and followed up, with tests for initial HCV infection every 1–3 months. All patients would ideally undergo HCV RNA testing to improve early detection; those infected for the first time would always have this test to characterise the course of primary HCV infection. Investigators would collect detailed information about HCV risk behaviour, including any longitudinal changes. Primary HCV infection cases with viral clearance would be followed up longitudinally for detection of HCV reinfection, with the same testing intervals as for initial detection. Individuals reinfected would be followed up for a long period to establish viraemia status and the incidence and course of further reinfection events. Blood samples would have to be taken during primary HCV infection and reinfection with standardised collection methods and stored for detailed immunological and virological studies. Finally, HCV reinfection would be confirmed through phylogenetic characterisation of initial and reinfection strains.

Without prospective studies appropriately designed to address whether HCV clearance provides protection against reinfection, pooling of information from existing cohorts with sufficient data is one way to move forward. The International Collaboration of Incident HIV and Hepatitis C in Injecting Cohorts (InC³) was established to create a merged multicohort project of pooled data from well characterised cohorts of IDUs with acute HCV, to enable new in-depth studies not possible from each individual study, and to bring together researchers across disciplines. InC³ has successfully pooled behavioural, clinical, and virological data from 539 participants with acute HCV infection from nine cohorts in Australia, Canada, Europe, and the USA.84

Conclusions

Data from chimpanzee and human studies of primary HCV infection, viral clearance, and HCV reinfection indicate that previous HCV infection is unlikely to provide substantial levels of acquired sterilising immunity. However, characterisation of the course of primary HCV infection and reinfection suggests that some protection against persistent HCV reinfection is developed through previous HCV infection.

Therefore, a vaccine that enhances spontaneous clearance of primary HCV could be more feasible than would a vaccine that prevents initial HCV infection.20 The primary goal of such a vaccine would be to prevent the development of chronic HCV infection after repeat exposures. The prevention of chronic HCV infection would be a suitable endpoint, because chronic—not acute—HCV infection is associated with HCV-related morbidity and mortality.

Search strategy and selection criteria.

We searched Medline with the terms “hepatitis C”, “HCV”, “reinfection”, “re-infection”, “drug users”, “epidemiology”, “diagnosis”, “natural history”, and “spontaneous clearance” to identify reports published in English before Sept 15, 2011. The reference lists of identified reports were manually searched for further relevant papers. Key abstracts at international meetings were also included. We selected reports on the basis of relevance to design, implementation, and analysis of studies related to HCV reinfection in injecting drug users and then assessed them for quality of methods and relevance of results.

Acknowledgments

Maria Prins was a Senior Visiting Fellow at the Kirby Institute for Infection and Immunity in Society, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia when she drafted parts of the manuscript. We thank Campbell Aitken (Burnet Institute, Australia), Jennifer Evans (University of California San Francisco, USA), Thijs van de Laar (Amsterdam Public Health Service, Netherlands), Bart Grady (Amsterdam Public Health Service, Netherlands), and Charlotte van den Berg (Amsterdam Public Health Service, Netherlands) for assisting with the preparation of data; and Tanya Applegate (Kirby Institute for Infection and Immunity in Society, Australia) for her constructive comments during the preparation of this report. This report was funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent the position of the Australian Government. JG is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship. MP was supported by the Public Health Service of Amsterdam. MH was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Researcher Fellowship. ALC and WOO were supported by the US National Institutes of Health (U19 AI040035 and R01 AI077757), the Damon Runyon Foundation, and the Dana Foundation. GL is supported by the US National Institutes of Health (U19 AI066345 and U19 AI082630). KP was supported by US National Institutes of Health (5R01DA016017 and 1R01DA031056-01A1) and the UCSF Liver Center (UCSF P30 DK026743). ARL and GJD were supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowships.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Contributors

JG, MP, and GD developed the outline and concept for the Review, and finalised the first draft. All authors assisted in writing of the first draft according to their area of expertise and contributed to the final editing of the report.

References

- 1.Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359–62. doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Micallef JM, Kaldor JM, Dore GJ. Spontaneous viral clearance following acute hepatitis C infection: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassett SE, Guerra B, Brasky K, et al. Protective immune response to hepatitis C virus in chimpanzees rechallenged following clearance of primary infection. Hepatology. 2001;33:1479–87. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Major ME, Mihalik K, Puig M, et al. Previously infected and recovered chimpanzees exhibit rapid responses that control hepatitis C virus replication upon rechallenge. J Virol. 2002;76:6586–95. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6586-6595.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nascimbeni M, Mizukoshi E, Bosmann M, et al. Kinetics of CD4+ and CD8+ memory T-cell responses during hepatitis C virus rechallenge of previously recovered chimpanzees. J Virol. 2003;77:4781–93. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4781-4793.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanford RE, Guerra B, Chavez D, et al. Cross-genotype immunity to hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2004;78:1575–81. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1575-1581.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prince AM, Brotman B, Lee DH, et al. Protection against chronic hepatitis C virus infection after rechallenge with homologous, but not heterologous, genotypes in a chimpanzee model. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1701–09. doi: 10.1086/496889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoukry NH, Grakoui A, Houghton M, et al. Memory CD8+ T cells are required for protection from persistent hepatitis C virus infection. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1645–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerlach JT, Diepolder HM, Zachoval R, et al. Acute hepatitis C: high rate of both spontaneous and treatment-induced viral clearance. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:80–88. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00668-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osburn WO, Fisher BE, Dowd KA, et al. Spontaneous control of primary hepatitis C virus infection and immunity against persistent reinfection. Gastroenterology. 2009;138:315–24. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox AL, Page K, Bruneau J, et al. Rare birds in North America: acute hepatitis C cohorts. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:26–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehta SH, Cox A, Hoover DR, et al. Protection against persistence of hepatitis C. Lancet. 2002;359:1478–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08435-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grebely J, Conway B, Raffa JD, Lai C, Krajden M, Tyndall MW. Hepatitis C virus reinfection in injection drug users. Hepatology. 2006;44:1139–45. doi: 10.1002/hep.21376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Micallef JM, Macdonald V, Jauncey M, et al. High incidence of hepatitis C virus reinfection within a cohort of injecting drug users. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:413–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aitken CK, Lewis J, Tracy SL, et al. High incidence of hepatitis C virus reinfection in a cohort of injecting drug users. Hepatology. 2008;48:1746–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.22534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Currie SL, Ryan JC, Tracy D, et al. A prospective study to examine persistent HCV reinfection in injection drug users who have previously cleared the virus. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:148–54. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van de Laar TJ, Molenkamp R, van den Berg C, et al. Frequent HCV reinfection and superinfection in a cohort of injecting drug users in Amsterdam. J Hepatol. 2009;51:667–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page K, Hahn JA, Evans J, et al. Acute hepatitis C virus infection in young adult drug users: a prospective study of incident infection, resolution and reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1216–26. doi: 10.1086/605947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grebely J, Pham ST, Matthews GV, et al. Hepatitis C virus reinfection and superinfection among treated and untreated participants with recent infection. Hepatology. 2012;55:1058–69. doi: 10.1002/hep.24754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halliday J, Klenerman P, Barnes E. Vaccination for hepatitis C virus: closing in on an evasive target. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10:659–72. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busch MP. Insights into the epidemiology, natural history and pathogenesis of hepatitis C virus infection from studies of infected donors and blood product recipients. Transfus Clin Biol. 2001;8:200–06. doi: 10.1016/s1246-7820(01)00125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox AL, Netski DM, Mosbruger T, et al. Prospective evaluation of community-acquired acute-phase hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:951–58. doi: 10.1086/428578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Page-Shafer K, Pappalardo BL, Tobler LH, et al. Testing strategy to identify cases of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and to project HCV incidence rates. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:499–506. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01229-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orland JR, Wright TL, Cooper S. Acute hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2001;33:321–27. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcellin P. Hepatitis C: the clinical spectrum of the disease. J Hepatol. 1999;31 (suppl 1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dore GJ, Hellard M, Matthews GV, et al. Effective treatment of injecting drug users with recently acquired hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:123–35. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grebely J, Matthews GV, Petoumenos K, Dore GJ. Spontaneous clearance and the beneficial impact of treatment on clearance during recent hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2009;17:896. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page K, Hahn JA, Evans J, et al. Acute hepatitis C virus infection in young adult injection drug users: a prospective study of incident infection, resolution, and reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1216–26. doi: 10.1086/605947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosley JW, Operskalski EA, Tobler LH, et al. The course of hepatitis C viraemia in transfusion recipients prior to availability of antiviral therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:120–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott JD, McMahon BJ, Bruden D, et al. High rate of spontaneous negativity for hepatitis C virus RNA after establishment of chronic infection in Alaska Natives. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:945–52. doi: 10.1086/500938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seeff LB. The history of the “natural history” of hepatitis C (1968–2009) Liver Int. 2009;29 (suppl 1):89–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang CC, Krantz E, Klarquist J, et al. Acute hepatitis C in a contemporary US cohort: modes of acquisition and factors influencing viral clearance. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1474–82. doi: 10.1086/522608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diepolder HM. New insights into the immunopathogenesis of chronic hepatitis C. Antiviral Res. 2009;82:103–09. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.02.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Post J, Ratnarajah S, Lloyd AR. Immunological determinants of the outcomes from primary hepatitis C infection. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:733–56. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8270-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rehermann B. Hepatitis C virus versus innate and adaptive immune responses: a tale of coevolution and coexistence. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1745–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI39133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blackard JT, Shata MT, Shire NJ, Sherman KE. Acute hepatitis C virus infection: a chronic problem. Hepatology. 2008;47:321–31. doi: 10.1002/hep.21902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lemon SM. Induction and evasion of innate antiviral responses by hepatitis C virus. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22741–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.099556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowen DG, Walker CM. Adaptive immune responses in acute and chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Nature. 2005;436:946–52. doi: 10.1038/nature04079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takaki A, Wiese M, Maertens G, et al. Cellular immune responses persist and humoral responses decrease two decades after recovery from a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C. Nat Med. 2000;6:578–82. doi: 10.1038/75063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rauch A, Gaudieri S, Thio C, Bochud PY. Host genetic determinants of spontaneous hepatitis C clearance. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:1819–37. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tillmann HL, Thompson AJ, Patel K, et al. A polymorphism near IL28B is associated with spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus and jaundice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1586–92. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grebely J, Petoumenos K, Hellard M, et al. Potential role for Interleukin-28B genotype in treatment decision-making in recent hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2010;52:1216–24. doi: 10.1002/hep.23850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ray SC, Wang YM, Laeyendecker O, Ticehurst JR, Villano SA, Thomas DL. Acute hepatitis C virus structural gene sequences as predictors of persistent viremia: hypervariable region 1 as a decoy. J Virol. 1999;73:2938–46. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2938-2946.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farci P, Shimoda A, Coiana A, et al. The outcome of acute hepatitis C predicted by the evolution of the viral quasispecies. Science. 2000;288:339–44. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harris HE, Eldridge KP, Harbour S, Alexander G, Teo CG, Ramsay ME. Does the clinical outcome of hepatitis C infection vary with the infecting hepatitis C virus type? J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:213–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grebely J, Raffa JD, Lai C, Krajden M, Conway B, Tyndall MW. Factors associated with spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus among illicit drug users. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:447–51. doi: 10.1155/2007/796325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strasfeld L, Lo Y, Netski D, Thomas DL, Klein RS. The association of hepatitis C prevalence, activity, and genotype with HIV infection in a cohort of New York City drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:356–64. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200307010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garten RJ, Lai SH, Zhang JB, Liu W, Chen J, Yu XF. Factors influencing a low rate of hepatitis C viral RNA clearance in heroin users from Southern China. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1878–84. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang M, Rosenberg PS, Brown DL, et al. Correlates of spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus among people with hemophilia. Blood. 2006;107:892–97. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Operskalski EA, Mack WJ, Strickler HD, et al. Factors associated with hepatitis C viremia in a large cohort of HIV-infected and -uninfected women. J Clin Virol. 2008;41:255–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas DL, Astemborski J, Rai RM, et al. The natural history of hepatitis C virus infection: host, viral, and environmental factors. JAMA. 2000;284:450–56. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Melendez-Morales L, Konkle BA, Preiss L, et al. Chronic hepatitis B and other correlates of spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus among HIV-infected people with hemophilia. AIDS. 2007;21:1631–36. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32826fb6d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piasecki BA, Lewis JD, Reddy KR, et al. Influence of alcohol use, race, and viral coinfections on spontaneous HCV clearance in a US veteran population. Hepatology. 2004;40:892–99. doi: 10.1002/hep.20384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soriano V, Mocroft A, Rockstroh J, et al. Spontaneous viral clearance, viral load, and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in HIV-infected patients with anti-HCV antibodies in Europe. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1337–44. doi: 10.1086/592171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shores NJ, Maida I, Soriano V, Nunez M. Sexual transmission is associated with spontaneous HCV clearance in HIV-infected patients. J Hepatol. 2008;49:323–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2009;461:798–801. doi: 10.1038/nature08463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rauch A, Kutalik Z, Descombes P, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B is associated with chronic hepatitis C and treatment tailure: a genome-wide association study. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1338–45. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marcello T, Grakoui A, Barba-Spaeth G, et al. Interferons alpha and lambda inhibit hepatitis C virus replication with distinct signal transduction and gene regulation kinetics. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1887–98. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Su AI, Pezacki JP, Wodicka L, et al. Genomic analysis of the host response to hepatitis C virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15669–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202608199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Post JJ, Pan Y, Freeman AJ, et al. Clearance of hepatitis C viremia associated with cellular immunity in the absence of seroconversion in the hepatitis C incidence and transmission in prisons study cohort. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1846–55. doi: 10.1086/383279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zeremski M, Shu MA, Brown Q, et al. Hepatitis C virus-specific T-cell immune responses in seronegative injection drug users. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:10–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dowd KA, Netski DM, Wang XH, Cox AL, Ray SC. Selection pressure from neutralizing antibodies drives sequence evolution during acute infection with hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2377–86. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bartosch B, Bukh J, Meunier JC, et al. In vitro assay for neutralizing antibody to hepatitis C virus: evidence for broadly conserved neutralization epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14199–204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335981100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Logvinoff C, Major ME, Oldach D, et al. Neutralizing antibody response during acute and chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10149–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403519101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meunier JC, Engle RE, Faulk K, et al. Evidence for cross-genotype neutralization of hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles and enhancement of infectivity by apolipoprotein C1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4560–65. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501275102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lavillette D, Morice Y, Germanidis G, et al. Human serum facilitates hepatitis C virus infection, and neutralizing responses inversely correlate with viral replication kinetics at the acute phase of hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:6023–34. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6023-6034.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pestka JM, Zeisel MB, Blaser E, et al. Rapid induction of virus-neutralizing antibodies and viral clearance in a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6025–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607026104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Prince AM, Brotman B, Huima T, Pascual D, Jaffery M, Inchauspe G. Immunity in hepatitis C infection. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:438–43. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.3.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Farci P, Alter HJ, Govindarajan S, et al. Lack of protective immunity against reinfection with hepatitis C virus. Science. 1992;258:135–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1279801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grakoui A, Shoukry NH, Woollard DJ, et al. HCV persistence and immune evasion in the absence of memory T cell help. Science. 2003;302:659–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1088774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lai ME, Mazzoleni AP, Argiolu F, et al. Hepatitis C virus in multiple episodes of acute hepatitis in polytransfused thalassaemic children. Lancet. 1994;343:388–90. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aitken CK, Lewis J, Tracy SL, et al. High incidence of hepatitis C virus reinfection in a cohort of injecting drug users. Hepatology. 2008;48:1746–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.22534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Micallef JM, Macdonald V, Jauncey M, et al. High incidence of hepatitis C virus reinfection within a cohort of injecting drug users. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:413–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Osburn WO, Fisher BE, Dowd KA, et al. Spontaneous control of primary hepatitis C virus infection and immunity against persistent reinfection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:315–24. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pham ST, Bull RA, Bennett JM, et al. Frequent multiple hepatitis C virus infections among injection drug users in a prison setting. Hepatology. 2010;52:1564–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.23885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.den Hollander JG, Rijnders BJ, van Doornum GJ, van der Ende ME. Sexually transmitted reinfection with a new hepatitis C genotype during pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy. AIDS. 2005;19:639–40. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000163947.24059.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dove L, Phung Y, Bzowej N, Kim M, Monto A, Wright TL. Viral evolution of hepatitis C in injection drug users. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:574–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dore GJ, Micallef J. Low incidence of HCV reinfection: exposure, testing frequency, or protective immunity? Hepatology. 2007;45:1330. doi: 10.1002/hep.21577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van den Berg CH, Smit C, Bakker M, et al. Major decline of hepatitis C virus incidence rate over two decades in a cohort of drug users. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22:183–93. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-9089-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grebely J, Thomas DL, Dore GJ. HCV reinfection studies and the door to vaccine development. J Hepatol. 2009;51:628–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lloyd AR, Jagger E, Post JJ, et al. Host and viral factors in the immunopathogenesis of primary hepatitis C virus infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:24–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Neumann-Haefelin C, Spangenberg HC, Blum HE, Thimme R. Host and viral factors contributing to CD8+ T cell failure in hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4839–47. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i36.4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vickerman P, Grebely J, Dore GJ, et al. The more you look the more you find: effects of hepatitis C virus testing interval on re-infection incidence and clearance: implications for future vaccine study design. J Infect Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ infdis/jis213.. published online Mar 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grebely J, Dore GJ, Schim van der Loeff M, et al. on behalf of the Inc3 Collaborative Group. Factors associated with spontaneous clearance during acute hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2010;52 (suppl 2):S411. [Google Scholar]