Abstract

The presence of labile low-molecular-mass (LMM, defined as < 10 kDa) metal complexes in cells and super-cellular structures such as the brain has been inferred from chelation studies, but direct evidence is lacking. To evaluate the presence of LMM metal complexes in the brain, supernatant fractions of fresh mouse brain homogenates were passed through a 10 kDa cutoff membrane and subjected to size-exclusion liquid chromatography under anaerobic refrigerated conditions. Fractions were monitored for Mn, Fe, Co, Cu, Zn, Mo, S and P using an on-line ICP-MS. At least 30 different LMM metal complexes were detected along with numerous P- and S- containing species. Reproducibility was assessed by performing the experiment 13 times, using different buffers, and by examining whether complexes changed with time. Eleven Co, 2 Cu, 5 Mn, 4 Mo, 3 Fe and 2 Zn complexes with molecular masses < 4 kDa were detected. One LMM Mo complex comigrated with the molybdopterin cofactor. Most Cu and Zn complexes appeared to be protein-bound with masses ranging from 4 – 20 kDa. Co was the only metal for which the “free” or aqueous complex was reproducibly observed. Aqueous Co may be sufficiently stable in this environment due to its relatively slow water-exchange kinetics. Attempts were made to assign some of these complexes, but further efforts will be required to identify them unambiguously and to determine their functions. This is among the first studies to detect low-molecular-mass transition metal complexes in the mouse brain using LC-ICP-MS.

Introduction

Transition metals such as iron, copper, manganese, molybdenum, and cobalt are critical components of cells and super-cellular structures like the brain. They tend to be redox-active and have excellent catalytic properties that render them common residents in the active-sites of enzymes. However, many of those same properties can be deleterious to the cell, especially when their ligands are coordinated weakly. Labile FeII and CuI complexes in particular can react with H2O2 to generate •OH via the Fenton reaction.1, 2 Hydroxyl radicals and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) can damage DNA, proteins and membranes. Thus, trafficking newly-imported metal ions from the plasma membrane to various apo-protein targets requires chaperones that bind these metal ions weakly enough so that they can be transferred from one species to another while simultaneously avoiding dangerous side-reactions. Substantial progress has been made in understanding metal ion trafficking, but many molecular-level details remain unknown.3 Nowhere is metal ion trafficking more important than in the brain, since many neurodegenerative diseases are associated with metal ion accumulation.4, 5

The concentration of Fe in the brains of mice fed standard (50 mg Fe/kg) chow is ca. 350 μM, with ~ 50% present as ferritin, ~ 40% as Fe/S clusters and heme centers, and 5% - 9% as mononuclear nonheme high-spin (NHHS) FeII and FeIII species.6 Most Fe/S clusters and heme centers reside in mitochondrial respiratory complexes where they help provide chemical energy for the brain. Some NHHS FeII ions are found in the active sites of enzymes while others may be involved in trafficking. NHHS FeII complexes often have weakly-coordinating ligands and engage in Fenton chemistry.

Trafficking of metals involves protein chaperones that bind metal ions in one location of the cell and release them in another, e.g. to an apo-protein binding site during folding and maturation.7 Whether trafficking also involves low-molecular-mass (LMM) metal complexes is less certain. Such species may exist in aqueous regions of a cell, where they might interact with protein chaperones and/or pass through membrane-bound transporters. For example, Mrs3p/Mrs4p are membrane-bound mitochondrial proteins that transport Fe from the cytosol to the mitochondrial matrix.8 Although the structures of these two proteins are unknown, homologous structures suggest that the channels that pass through them are too small to accommodate a protein. This suggests that LMM Fe complexes, consisting of the metal ion coordinated by small organic or inorganic ligands, and/or by waters, pass through these transporters.

If LMM metal complexes are involved in trafficking, they should have weakly coordinating ligands that can be displaced by strong chelating agents. Pamp et al.9 concluded that labile Fe constitutes 0.2 – 3% of overall cellular Fe. In human cells containing 400 μM Fe,10 this corresponds to a collective labile Fe concentration of 1-10 μM. Using fluorescence sensors, Petrat et al. found that the concentration of chelatable iron in the cytosol of intact hepatocytes was in the same range, namely 5.8 ± 2.6 μM.11 According to Rauen et al. about 1% of cellular Fe exists in a pool that is not bound to ferritin or other proteins.12 They estimate that the concentration of chelatable Fe in liver mitochondria and in the cytosol is 12 μM13 and 6 μM11, respectively. Using chelators of different Fe affinities had no effect on the apparent size of the mitochondrial chelatable Fe pool, suggesting that the determined pool concentration (16 ± 2 μM) represents its “true” size. These estimates are substantially less than the concentration of NHHS FeII ions present within yeast mitochondria, as quantified by Mössbauer spectroscopy.14 Some Mössbauer-detectable NHHS FeII species may be protein-bound and not labile. Differences may also arise from the different organisms probed and/or different cellular metabolic growth modes. The Mössbauer-detected NHHS FeII ions are chelated by 1,10-phenantroline (Phen).14 This attenuates Fe/S cluster synthesis,15 strongly suggesting that these ions serve as feedstock for this process.

The roles of LMM Fe complexes in cells and the brain are unknown, but patterns are emerging suggesting involvement in development, aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Kaur et al.16 found an increase in the labile iron pool (LIP) in the brains of older mice, suggesting that such ions might be involved in aging. Wypijewska et al.17 found increased LIP in the Substantia nigra region of PD brains. Sohal et al.18 and Magaki et al.19 reported that 20% - 30% of nonheme Fe in the developing mouse brain was labile. Meguro et al.20 found that chelatable nonheme FeII and FeIII species were distributed heterogeneously throughout the rat brain and that the concentration of these species increased with age. Huang et al.21 reported that psychological stress expands the LMM FeIII and FeII pools in particular regions of the brain, as detected by Perl’s and Turnbull’s stains. Nothing is known regarding the particular complexes involved.

Although not formally a transition metal, Zn plays critical roles in brain metabolism.22 The concentration of Zn in the mouse brain is ca. 320 μM,6 most of which is bound to metalloproteins. Metallothioneins are the primary intracellular Zn-buffering proteins. Metallothionein III in the brain has a molecular mass (MM) of ca. 7 kDa and contains 8-11 Zn binding sites.23 Zn is also found in aggregated amyloid beta protein filaments in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), and is associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, epilepsy, strokes, depression, and schizophrenia.24 Protein-based and non-protein-based fluorescent probes have been used to image mobile Zn ions in cells and tissues.25, 26 Palmer and coworkers targeted protein-based FRET fluorescence sensors to the mitochondria, ER and Golgi of HeLa cells, and estimated the presence of such pools at low pM concentrations.27, 28 The detected concentration of cytosolic Zn was also extremely low, namely 80 pM. In contrast, high concentrations of Zn (estimated to be mM levels) are found in synaptic vesicles within neurons that use glutamate as a neurotransmitter.29 The synaptic Zn pool has been detected by Zn-specific fluorescent dyes.30,31 These vesicles are located primarily in the cerebral cortex and limbic structures. Labile Zn ions enter these vesicles via the membrane-bound protein ZnT3 and are released upon synaptic activation.32 This pool modulates the overall excitability of the brain, and is involved in signal transduction, memory and learning.

Copper is present in the mouse brain at low concentrations (~ 5 μM)6 but it is no less important than Fe or Zn. Cu plays essential roles in respiration, oxidative stress response, and other enzymatic activities.33 Cu ions in the brain parenchyma are involved in the metabolism of neurotransmitters and myelination.34

Numerous proteins are known to be involved in Cu trafficking. Ctr1 is a transporter on the plasma membrane that brings Cu into the cell.35 Cellular Cu can be stored in metallothionein, transported to mitochondria, incorporated into apo-Cu/Zn SOD, or transported to the Golgi apparatus for export from the cell.34 Cu-containing ceruloplasmin helps distribute and metabolize Cu, and it may help Fe efflux from the brain.36 Cox17 is an 8.0 kDa protein that transfers cytosolic Cu to mitochondria for incorporation into apo-cytochrome c oxidase.37 CCS1 is a trimer with 9 kDa subunits which functions to insert Cu into apo-Cu/Zn SOD.38,39 The concentration of CCS1 is sensitive to intracellular levels of Cu. Atx1 is an 8.2 kDa copper-binding chaperone that transports Cu to the Cu-ATPases in the trans-Golgi network. These proteins, Atp7a and Atp7b, deliver Cu for incorporation into proteins.40 When intracellular Cu concentration exceeds some setpoint value, they export Cu from the cell.

The presence of a labile Cu pool is less certain than that for Fe or Zn. Using highly selective ratiometric fluorescent reporters for CuI ions, Domaille et al. found an ascorbate-induced increase in the labile CuI pool in HEK 293T cells.41 Hirayama et al. used a fluorescent sensor to visualize labile CuI pools in mice.42

The mouse brain contains ~14 μM Mn, ~ 400 nM Mo, and ~ 30 nM Co, respectively.6 Some Mn is incorporated into mitochondrial superoxide dismutase which functions to diminish oxidative stress.43 Mn levels in the brain are elevated in patients with AD and Prion disease.44 Mo is coordinated to the molybdopterin cofactor in molybdenum hydroxylases.45 A deficiency of this cofactor causes seizures and death in newborns.46,47 Cobalt metabolism in the brain includes lipid biosynthesis and C1 metabolism.48,49 Co is present in coenzyme B12 bound in methionine synthase.50 This enzyme functions in methionine metabolism, which includes methyl group transfer reactions involving choline, folate and S-adenosyl-methionine.51

In this study, we have evaluated the presence of LMM metal complexes in the mouse brain. Rather than using specific chelators to identify such species, we have detected them using anaerobic liquid chromatography with an on-line ICP-MS following the approach of Adams and coworkers who explored the metalloproteome of a prokaryote.52 We report here that the brain contains a limited number of LMM Fe, Co, Mn, Mo, Cu and Zn complexes. These complexes were enumerated and characterized in terms of concentration and approximate MM. A few species were tentatively assigned.

Experimental Procedures

Chemicals and Standards

The water used was house-distilled, deionized using ion-exchange columns (Thermo Scientific 09-034-3), and then distilled again using a sub-boiling still (Savillex DST-1000). Cytochrome c (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), aprotinin (bovine lung), ATP, ADP, AMP, and cyanocobalamin were from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Inositol hexaphosphate (IP6), oxidized and reduced glutathione, sodium molybdate, and sodium phosphate were from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo, USA). The molybdopterin cofactor was isolated as described53 from xanthine oxidase. The sample buffer was 20 mM Tris (Fisher) pH 7.4.

Animal care and dissections

ICR (Imprinting Control Region) outbred mice were raised and manipulated in accordance with the TAMU Animal Care and Use committee (AUP 2010-226). Mice were housed in disposable plastic cages (Innovive Innocage Static Short) with all-plastic water bottles and plastic feeders with zinc electroplated reinforcements. Mice were fed Fe-deficient chow (Harlan Laboratories, Inc. Teklad ID TD.80396.PWD) supplemented with 50 mg/Kg of Fe citrate. Mice were euthanized by an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine as described.6 Immediately after breathing ceased and the heart stopped beating, animals were imported into a refrigerated (5–10 °C) Ar-atmosphere glove box (MBraun Labmaster) containing 2–20 ppm O2, as monitored by a Teledyne O2 analyzer (Model 310). From this point forward, all sample manipulations were performed in a glove box unless mentioned otherwise.

Preparation of LMM brain extract

Animals were perfused with degassed heparinized Ringer’s buffer at 1.0 mL/min for 0.5 min/g mouse, and then dissected as described.6 Immediately after isolation, 3 - 4 brains were added to a known volume (2 – 3 mL) of degassed 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4). The solution was homogenized for 1 min using a plastic rotary knife inserted into a tissue grinder (Omni TH). The resulting homogenate was disrupted by nitrogen cavitation (model 4639, Parr Instruments) at 800 psi for 10 min. The resulting extract was treated with Triton X-100 and Sodium deoxycholate (final concentrations of 1% (v/v) and 1% (w/v), respectively) for 10 min. The sample was removed from the box in an air-tight centrifuge bottle and spun at 110,000×g for 30 min. The bottle was returned to the box and the resulting supernatant fraction (~ 3 mL) was transferred to a stirred cell concentrator (Amicon Model 8003, Millipore) fitted with a 10 kDa cutoff membrane (YM-10, Millipore). The supernatant was passed through the membrane with a head pressure of 90 psi Ar, and ~ 2 mL of the flow-through solution (FTS) was collected in a plastic screw-top tube. The tube was sealed with electrical tape, placed inside of a second container that was then sealed, removed from the box, and immediately imported into a second glovebox that contained the LC. In one experiment, the FTS was split into two aliquots, one of which was spiked with 100 μL of 180 nM stock solutions (prepared in 20 mM Tris pH 7.4) of FeSO4, CuCl2, MnCl2, CoCl2, ZnCl2 and Na2MoO4. After 3 hrs, aliquots were injected, one after the other, into the LC-ICP-MS system.

Elemental Concentrations in Flow-Through Solutions

Aliquots (150 μL) of the FTS for each run were placed into 15 mL plastic screw-top tubes (BD Falcon) containing 100 μL of concentrated trace-metal-grade (TMG) nitric acid (6.4 M final concentration). After ~ 12 hr at 90 °C, samples were diluted with 9.75 mL of distilled-and-deionized water, affording a final acid concentration of 0.14 M. Calibration curves were prepared from standard solutions containing P, S, Co, Cu, Zn, Fe, Mn, and Mo (Inorganic Ventures, Christiansburg Virginia, USA) at known concentrations, prepared in trace-metal-grade nitric acid and diluted using distilled-and-deionized water. Data were collected in He collision mode using ICP-MS (model 7700x, Agilent Technologies, Tokyo, Japan). Elemental concentrations were determined using the calibration curve. Values obtained were adjusted for dilution factors.

Chromatography and instrumentation

HPLC separations were carried out in a refrigerated Ar-atmosphere glove box (Labmaster, Mbraun USA) using an Agilent 1200 Bioinert LC composed of a metal-free Infinity 1260 Quaternary Pump equipped with a manual injection valve fitted with a 500 μL PEEK injection loop. Two size-exclusion Superdex Peptide GL 10/300 columns (300 × 10 mm, GE Life Science, USA) were combined in series using a male-to-male union connector. The mobile phase was 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4). Post-column eluent flow (0.35 mL/min) was mixed in real-time with a solution of 4% trace-metal-grade nitric acid plus 100 μg/L 116In, diluting the eluent 2-fold. The resulting solution flowed into an on-line inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS) (7700x, Agilent Technologies, Tokyo Japan), and 31P, 34S, 55Mn, 35Cu, 59Co, 65Zn, 95Mo, 56/57Fe, and 116In were detected. Indium was used as an internal standard to monitor plasma suppression. Other ICP-MS conditions: RF power, 1500 W; Ar flow rate, 15 L/min; collision cell He flow rate, 4.3 mL/min; sampling/skimmer cones, Pt, Pt; dwell time, 0.2 sec; internal standard pump rate, 0.35 mL/min.

The column was cleaned after each run using 10 column volumes (CVs) of a chelator cocktail at a flow rate of 150 μL/min and then regenerated with the elution buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4). The chelator cocktail was composed of 20 mM Tris pH 8.0 plus 10 μM each of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, tetrakis-(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN), Phen and 2,2′-bipyridine.

Molecular Mass calibration

The MM associated with each chromatographic peak was calculated using a standard curve constructed from 14 known species (Table S1). Standard stock solutions were prepared in 20 mM Tris pH 7.4, affording concentrations ranging from 1 - 200 μM. Each solution was injected individually onto the column. Elution volumes Ve were determined using either the ICP-MS or UV-vis detector response. In cases where multiple forms were evident (GSH, GSSG, ATP, ADP, and AMP), the peak with the MM nearest to the known mass of the species was assigned to that species. Void volume V0 was determined using Blue Dextran (MM 2000 kDa). The logarithm of the MM was plotted vs. the ratio Ve/V0 (Fig. S1). The best-fit linear regression curve was constructed through the data points.

Results

The objective of this study was to determine whether the mouse brain contained LMM transition metal complexes detectable by LC-ICP-MS. We avoided oxidizing FeII-containing species due to concern that endogenous ligands might dissociate upon oxidation and be replaced by waters, rendering insoluble aqueous FeIII ions that would adsorb to the column. Once animals were euthanized, all procedures involving samples were performed in a refrigerated Ar-atmosphere glove box. In each experiment, isolated brains were homogenized and centrifuged, and then supernatants were passed through a 10 kDa cut-off membrane. Because such complexes could potentially be highly dynamic and unstable, samples were prepared for the LC as fast as possible; FTSs were injected onto the LC column ca. 3 hrs after animals were euthanized. Experiments were performed 13 times to assess reproducibility.

Elemental concentrations in the FTSs were determined and corrected for dilution, affording estimates for the collective concentrations of all the LMM species for these elements in the brain. The results were (in μM): Co, 0.06 ± 0.01; Mo, 0.3 ± 0.1; Mn, 0.8 ± 0.1; Cu, 4.2 ± 0.2; Fe, 18 ± 1; Zn, 44 ± 7; S, 1500 ± 70; and P, 11,000 ± 1000 (Table S2 lists individual values). Assuming the total metal concentrations in the brain mentioned in the Introduction (except for Co, which was found in the current study to be present in the brain at 88 ± 5 nM), the percentages of these elements in the brain that passed through the LMM membrane were: Co, 66 ± 10; Mo, 67 ± 25; Mn, 6 ± 1, Cu, 84 ± 12; Fe, 5 ± 0.4; Zn, 14 ± 2; S, 9 ± 2; P, 12 ± 3. Thus, LMM species represent large percentages of total Co, Mo and Cu ions in the brain, but smaller percentages of Mn, Fe, Zn, S and P. For Fe in particular, the calculated percentage is comparable to previous chelation-based determinations in human cells (see Introduction).

Given the potential lability of these metal complexes, we evaluated the percentage of the metals that eluted from the column, normalized to the amount loaded. The averages of three runs were: Mo, 74 ± 12; Mn, 93 ± 4; Fe, 89 ± 7; Co, 93 ± 4; Cu, 84 ± 6; Zn, 92 ± 3; P, 91 ± 3 and S, 92 ± 6, respectively. These values indicate that the majority of the metal-containing species in the FLSs eluted from the column. The small percentage of each metal that did not elute demonstrates the importance of washing the column extensively between runs.

A total of 13 runs were performed; of these, 11 were analyzed. The two excluded runs had peak linewidths 2 - 3 fold greater than the others (suggesting a problem with the column). Thus, our analyses were essentially free of subjective bias. Stacks of individual chromatograms for each element are given in the Electronic Supplementary Information (Figures S2 – S9). Reproducibility was acceptable but there were noticeable variations. P and S chromatograms were the most reproducible, in that the same sets of peaks, with similar relative area-ratios, were observed in each run. The Ve associated with each peak were not perfectly matched from one chromatogram to another, and so small shifts in the volume dimension, corresponding to no more than 0.24 mL, were allowed to align S and P peaks to the greatest extent possible. The identical alignment offsets were used for the corresponding Mo, Mn, Co, Fe, Cu and Zn chromatograms generated in the same run. In this way, the S and P chromatograms served as an internal calibration to align the metal-based chromatograms. Data sets were not adjusted further.

We considered that some peaks might arise from degradation products of the brain, despite using freshly prepared FTS and working quickly. To examine this, a FTS was left for 13 days in a refrigerated box prior to passage through the column. The resulting chromatograms, compared to those obtained using fresh FTS, revealed virtually no change in relative peak areas and distributions (Fig. S10). We conclude that our samples did not degrade on the time scale of the experiment.

We also considered that our results might depend on the FTS buffer employed. To examine this, the buffer was switched from Tris to HEPES (both 20 mM at pH 7.4). The resulting chromatograms revealed no significant differences (Fig. S11). Remaining run-to-run variations probably arose from animal-to-animal differences. To minimize these, mice were euthanized at approximately the same time of day (10 am – 12 noon). Age and gender differences were considered as variational factors, but no correlations were obvious. In analyzing datasets, we assumed that any peak observed in ≥ 50% of the metal-matched datasets represented a real species in the brain. Peaks observed in > 25% and < 50% of chromatograms were viewed as probably reflecting real species. Peaks observed in ≤ 25% of chromatograms were considered artifacts and were not included in downstream analyses. Averages for peaks that were reproducibly present, according to these criteria, are summarized in Table 1. MMs for each species were estimated from Ve and the best-fit linear regression standard-curve line.

Table 1.

Low-Molecular-Mass Metal Complexes in the Mouse Brain. Confidence was defined as the number of chromatograms for a given element in which the peak was present divided by the total number of chromatograms for that element, multiplied by 100.

| Assigned Name |

Peak Center (mL) |

Peak Width (mL) |

Molecular Mass (Da) |

Area (%) |

[Metal]Brain (μM) |

Confidence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHMM | V < 18 mL | N/A | 24,000 – 48,000 | 43 ± 14 | 4600 ± 1500 | 100 |

| P2490 | 29.5 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 2490 ± 150 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 90 ± 50 | 67 |

| P1950 | 30.7 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 1950 ± 240 | 1.2 ± 1 | 130 ± 110 | 92 |

| P1240 | 32.9 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1240 ± 100 | 7 ± 3 | 760 ± 320 | 100 |

| P1060 | 33.7 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1060 ± 40 | 4 ± 3 | 430 ± 320 | 41 |

| P900 | 34.5 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 900 ± 60 | 3 ± 2 | 320 ± 220 | 92 |

| P630 | 36.2 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 630 ± 30 | 19 ± 13 | 2000 ± 1400 | 83 |

| P570 | 36.7 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 570 ± 20 | 15 ± 11 | 1600 ± 1200 | 67 |

| P530 | 37.1 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 530 ± 10 | 14 ± 10 | 1500 ± 1100 | 50 |

| P490 | 37.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 490 ± 10 | 13 ± 13 | 1400 ± 1400 | 58 |

| SHMM | V < 18 mL | n/a | 24,000 - 48,000 | 54 ± 10 | 800 ± 150 | 100 |

| S1540 | 31.8 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1540 ± 76 | 2.4 ± 1 | 35 ± 15 | 100 |

| S940 | 34.3 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 940 ± 73 | 1.4 ± 1 | 21 ± 15 | 100 |

| S570 | 36.7 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 570 ± 5 | 22 ± 13 | 320 ± 190 | 92 |

| S520 | 37.1 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 520 ± 7 | 17 ± 11 | 250 ± 160 | 100 |

| S370 | 38.8 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 370 ± 14 | 5 ± 1 | 74 ± 74 | 100 |

| CoHMM | V < 18 mL | n/a | 24,000 - 48,000 | 8 ± 7 | 0.005 ± 0.004 | 100 |

| Co1640 | 31.5 ± 0.8 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1640 ± 250 | 38 ± 16 | 0.020 ±0.009 | 100 |

| Co1380 | 32.4 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 1380 ± 80 | 18 ± 8 | 0.010 ± 0.004 | 100 |

| Co1130 | 33.4 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 1130 ± 140 | 15 ± 11 | 0.009 ± 0.006 | 100 |

| Co920 | 34.4 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 920 ± 90 | 3 ± 2 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 92 |

| Co900 | 34.5 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 1 | 900 ± 60 | 2 ± 1 | 0.001 ± 0.0005 | 50 |

| Co630 | 36.2 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 1 | 630 ± 40 | 5 ± 5 | 0.003 ± 0.003 | 75 |

| Co500 | 37.4 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 1 | 500 ± 30 | 3 ± 3 | 0.002 ± 0.002 | 75 |

| Co400 | 38.4 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 400 ± 20 | 2 ± 2 | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 58 |

| Co300 | 39.7 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 310 ± 30 | 1 ± 1 | 0.0008 ± 0.0004 | 75 |

| Co210 | 41.6 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 210 ± 20 | 2 ± 2 | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 85 |

| Coaq | 43.9 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | < 200 | 3 ± 3 | 0.002 ± 0.002 | 50 |

| CuHMM | V < 19.4 mL | n/a | 24,000 – 48,000 | 60 ±16 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 100 |

| Cu19390 | 19.5 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 19390 ± 440 | 23 ± 12 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 100 |

| Cu15670 | 20 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 15670 ± 610 | 13 ± 5 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 100 |

| Cu8650 | 23.4 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 8650 ± 500 | 2 ± 0.7 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 100 |

| Cu5680 | 25.5 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 5680 ± 280 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 100 |

| Cu4230 | 26.9 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 4230 ± 350 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 100 |

| Cu1020 | 33.9 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 1020 ± 140 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.01 ± 0.03 | 92 |

| Cu370 | 38.9 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 370 ± 20 | 0.8 ± 0.8 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 100 |

| ZnHMM | V < 18 mL | n/a | 24,000 – 48,000 | 86 ± 3 | 38 ± 1 | 100 |

| Zn19630 | 19.4 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 19630 ± 1610 | 8.5 ± 4 | 3.75 ± 2 | 100 |

| Zn16000 | 20.4 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 16000 ± 1640 | 5 ± 2 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 92 |

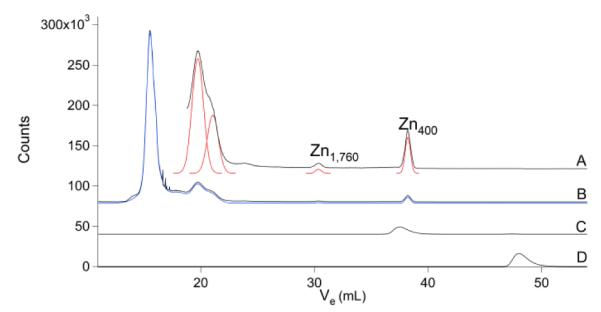

| Zn1760 | 31.2 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 1760 ± 180 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.18 ± 0.09 | 42 |

| Zn400 | 38.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 400 ± 8 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 67 |

| FeHMM | V < 18 mL | n/a | 24,000 - 48,000 | 98 ± 2 | 17.4 ± 0.4 | 100 |

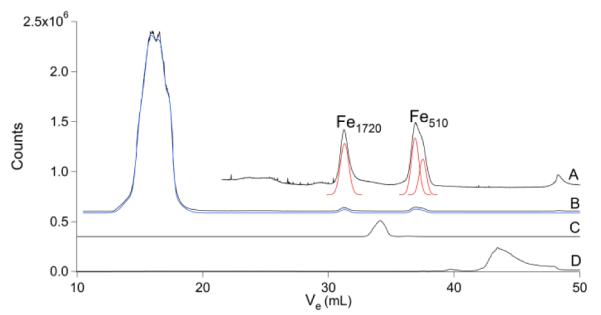

| Fe3320 | 28.1 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 3320 ± 270 | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 58 |

| Fe1720 | 31.3 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 1720 ± 40 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 58 |

| Fe510 | 37.3 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 510 ± 30 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.09 ± 0.05 | 75 |

| MnHMM | V < 18 mL | n/a | 24,000 - 48,000 | 77 ± 22 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 100 |

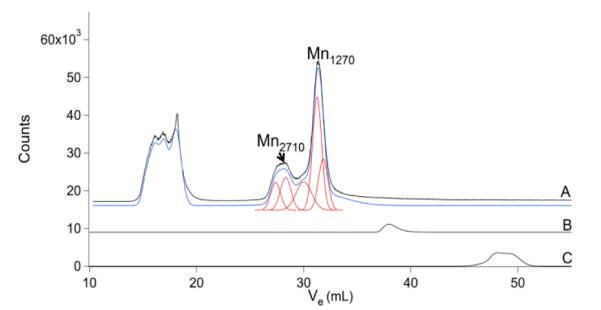

| Mn3810 | 27.4 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 3810 ± 190 | 3 ± 1 | 0.025 ± 0.008 | 50 |

| Mn2710 | 29.1 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 2710 ± 300 | 3 ± 2 | 0.025 ± 0.017 | 85 |

| Mn2040 | 30.5 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 2040 ± 320 | 11 ± 5 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 58 |

| Mn1680 | 31.4 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 1680 ± 100 | 17 ± 9 | 0.14 ± 0.08 | 50 |

| Mn1270 | 32.8 ± 1.3 | 1 ± 1 | 1270 ± 340 | 8 ± 7 | 0.07 ± 0.06 | 50 |

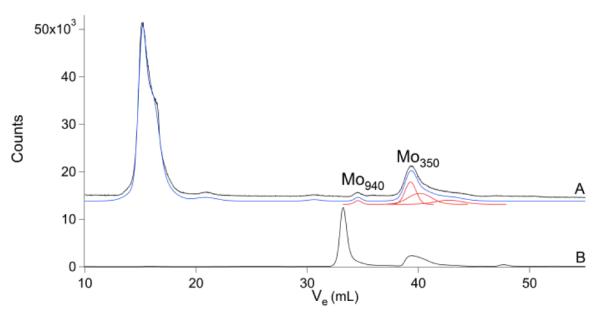

| MoHMM | V < 18 mL | n/a | 20,000 - 48,000 | 80 ± 10 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 100 |

| Mo940 | 34.3 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 940 ± 100 | 2 ± 2 | 0.005 ± 0.004 | 50 |

| Mo410 | 38.4 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 410 ± 50 | 5 ± 3 | 0.01 ± 0.008 | 58 |

| Mo350 | 39.1 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 350 ± 50 | 9 ± 5 | 0.02 ± 0.013 | 67 |

| Mo240 | 41.0 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 240 ± 30 | 4 ± 3 | 0.01 ± 0.008 | 67 |

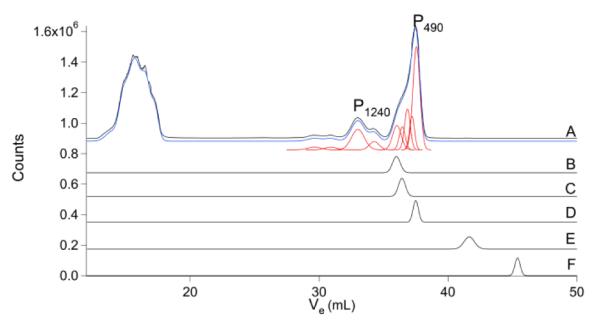

Representative chromatograms of the FLS for each element, along with various standard compounds, are shown in Figures 1 – 9. The P chromatogram (Fig. 1) exhibited two major regions of peaks. The high-molecular-mass (HMM) region corresponds to P-containing compounds with MMs between ca. 13 - 6 kDa (21 – 25 mL). P-compounds with MMs between 4 - 0.2 kDa (27– 41 mL) are included in the LMM region. The intermediate-molecular-mass (IMM) region between 4 – 6 kDa was effectively devoid of peaks.

Fig. 1.

Phosphorus chromatograms of brain FTS and various phosphorus-containing compounds. A, brain FTS; B, IP6; C, ATP; D, ADP; E, AMP, and F, HPO42−. Red lines in Figures 1 - 8 are simulations representing the LMM species listed in Table 1. The blue line is the overall simulation.

The ill-resolved shape of the HMM region suggested that multiple overlapping species contributed, and we did not attempt to decompose it. In contrast, the peaks in the LMM region were better resolved. These were simulated using the equation

| (1) |

where ω is the width of the peak and IV, I0, and Imax are the detector responses at any volume V, at volume V = 0, and at the volume corresponding to the peak maximum, respectively. We integrated the total area under the chromatogram along with the relative areas under the individual LMM peaks such that the percentage of the total eluent P due to each LMM peak (fcpd-i) could be determined. The concentration of each P-containing species represented by the LMM peaks in the brain ([Cpdi]) was calculated using the equation

| (2) |

where [P]fts is the concentration of P in the FTS and FD is the fold-dilution used to prepare the FTS starting from the intact brain. Similar equations were used to estimate the concentrations of all LMM metal and S compounds. Equation (2) assumes that the same proportion of each P compound was retained by the column. Maximum and minimum concentrations for each compound (Table 1) were estimated by assuming that the P retained by the column was exclusively either the P species of interest, or other P-containing species, respectively.

Eight species were used to simulate the LMM region of the P chromatogram (Fig. 1, Table 1). Each was designated by the element followed by a subscript indicating its approximate MM. The dominant P peak (P490) comigrated with ADP and was assigned as such. Authentic ATP migrated at a slightly smaller Ve and its peak fit in the HMM shoulder of P490 as long as the linewidth was increased. Alternatively, the peak for ATP and another species could both fit into this shoulder if narrower linewidths were assumed. IP6 binds Fe in cells and is thought to be involved in trafficking.54 However, no Fe peaks comigrated with Fe-bound IP6. The remaining P peaks were not assigned. Curiously, no peaks comigrated with AMP or orthophosphate.

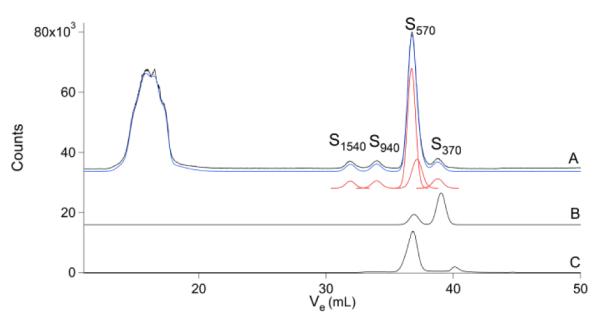

Peaks in the representative S chromatogram (Fig. 2) again segregated into HMM, IMM and LMM regions. Again, there were few, if any, S-containing species present in the IMM region. As with P, the S-containing species in the HMM region were poorly resolved and only the overall response in this region was determined by simulation. The LMM region contained 4 major resolved peaks. The dominant peak (S570) comigrated with GSSG. However, its broad linewidth suggested that GSSG and another S species with a similar MM contributed. Another peak (S370) nearly comigrated with GSH, and was assigned as such. The remaining two species, S1540 and S940 were not assigned. The ratio of peak areas for the oxidized and reduced glutathione species was ca. 4:1 GSSG:GSH, assuming that one of the two species that contributed to S570 was GSSG. This suggests a molar ratio of ca. 2:1 which is reasonably close to previously reported molar ratios for brain samples.55

Fig. 2.

Sulfur chromatograms of brain FTS and various S-containing compounds. A, brain FTS; B, glutathione, GSH; C, oxidized glutathione, GSSG. The authentic glutathione solution contained some GSSG, while the GSSG solution contained a contaminant.

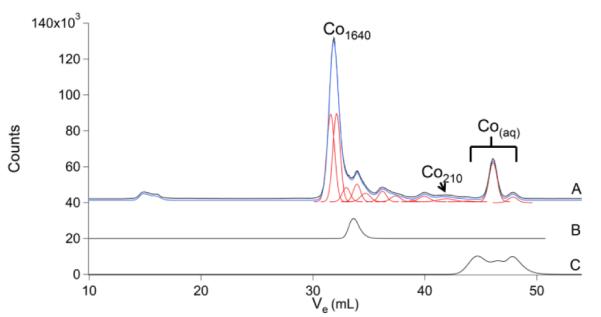

The Co chromatogram (Fig. 3) displayed numerous species in the LMM region, some HMM peak intensity, and little if any peaks in the IMM region. Of all metals detected, Co exhibited the greatest number of LMM species. Cyanocobalamin migrated just slightly slower than the dominant Co peak (Co1640), suggesting that Co1640 might arise from a related complex (e.g. adenosylcobalamin). Aqueous CoII ions migrated as multiple species, consistent with rapid ligand/proton exchange reactions.

Fig. 3.

Cobalt chromatograms of brain FTS and other Co species. A, brain FTS; B, cyanocobalamin; and C, aqueous Co. The three lowest MM simulations in the figure are considered a single species (Coaq) in Table 1.

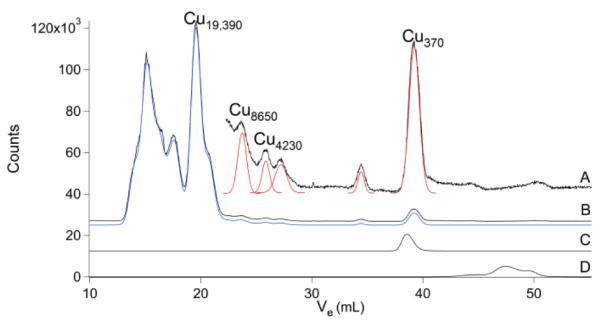

The representative Cu chromatogram (Fig. 4) indicated a HMM region containing ca. 5 – 6 reasonably resolved peaks, with MMs between 19 and 48 kDa. The IMM region was devoid of peaks, and the LMM region contained only ca. 2 peaks. Although the trace in Fig. 4 suggests a miniscule amount of aqueous Cu, this feature was not reliably present in other traces.

Fig.4.

Copper chromatograms of brain FTS and other Cu species. A, brain FTS ×15; B, brain FTS ×1; C, CuII(EDTA); and D, aqueous Cu.

The Zn chromatogram (Fig. 5) showed a well-resolved HMM region that included ca. 5 species. The IMM and LMM regions were virtually devoid of peaks.

Fig.5.

Zinc chromatograms of brain FTS. A, brain FTS ×16; B, brain FTS ×1; C, ZnII(TPEN); and D, aqueous Zn.

The Fe chromatogram (Fig. 6) showed a poorly resolved HMM region and an IMM region largely devoid of peaks. The LMM region included two significant peaks (Fe1720 and Fe510), but these were only observed in 58% and 75% of the chromatograms, respectively. In general, there was more variability in the Fe (and Mn) chromatograms than in chromatograms from the other metals. In most traces, the ultra LMM region was devoid of features (the trace shown in Fig. 6 shows such a feature, but it was not routinely observed).

Fig. 6.

Iron chromatograms of brain FTS. A, brain FTS ×15; B, brain FTS ×1; C, FeII(ATP); and D, aqueous Fe.

The Mn chromatogram (Fig. 7) included poorly resolved features in the HMM region, no features in the IMM region, and a few peaks in the LMM region. Mn1270 and the broad feature centered at ca. 28 mL were present in about half of the traces. The Mo chromatogram (Fig. 8) exhibited peaks in the HMM and LMM regions, while the IMM region was largely devoid of peaks. The major LMM peak (Mo350) comigrated with molybdopterin isolated from xanthine oxidase, suggesting that these peaks arise from the same or a closely related species.

Fig.7.

Manganese chromatograms of brain FTS and other Mn species. A, brain FTS; B, MnII(EDTA); and C, aqueous Mn.

Fig.8.

Molybdenum chromatograms of brain FTS and molybdopterin extract from xanthine oxidase. A, brain FTS; and B, molybdopterin. The intense peak in B with MM ~1.5 kDa was not assigned.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to determine whether the mouse brain contains LMM metal complexes, defined as Mo, Mn, Fe, Co, Cu and Zn complexes possessing MMs < 10 kDa. Rather than using chelators, our approach was to detect such species directly, using ICP-MS to monitor metals eluting from our LMM size-exclusion chromatography column. We were careful to avoid oxidation of any redox-active complexes, by working in an inert-atmosphere glovebox. We attempted to limit ligand substitution reactions by minimizing the time between euthanizing the animals and loading the LC column, and by running the column at low temperature. We distinguished “real” from artifactual complexes by repeating the experiment 13 times and assigning a confidence probability to each species in accordance with the proportion of runs in which the species was observed (Table 1). Our results were independent of buffer used. The vast majority of metal ions loaded on the column did not adhere to it.

By these criteria, our results indicate that there are 11 Co, 5 Cu, 5 Mn, 4 Mo, 3 Fe, and 2 Zn LMM complexes in the mouse brain. Of these 30 LMM metal complexes, only 2 – 3 have masses suggesting protein ligation (Cu8650, Cu5680 and perhaps Cu4230). The rest have lower MMs which suggest either small peptides as ligands or perhaps organic/inorganic ligands.

Except for Cu, all of the metals displayed a significant gap between one edge of the HMM region (with MMs > ~ 20 kDa) and one edge of the LMM region (with MMs < 4 kDa). The absence of metal complexes between these two regions implies that the division into such groups is not arbitrary. Zhuang et al. reported that the shortest (non-alternatively spliced) protein in the mouse genome is 38 residues, which corresponds to 4.2 kDa.56 This suggests that the complexes in the HMM region are exclusively protein-based and it raises the possibility that the metal complexes in the LMM region are either non-proteinaceous or have peptides arising from post-translational truncations. Large natural products and siderophores (e.g. actinomycin D, glycosylated antibiotics, pyoverdine) have MMs of ca. 1.5 kDa.

Of the metals examined, Co exhibited the most LMM complexes and perhaps the least protein-based species. Cu and Zn displayed the opposite pattern, with numerous well-resolved metal-bound proteins and few non-proteinaceous complexes.

Our results impact the issue of whether cells contain “free” aqueous metal ions. They indicate that there are significant concentrations of aqueous Co ions in the brain, but do not provide clear evidence of aqueous Cu, Zn, Mn, Mo or Fe ions. ICP-MS is quite sensitive, such that the concentration of aqueous metal ion would need to be < 10 nM (ca. 103 ions per cells; see Table S3) to escape detection. In a seminal study published over a decade ago, O’Halloran and coworkers argued that there are no “free” or aqueous Cu ions in the cell, and that Cu trafficking exclusively involves transferring Cu ions from one protein chaperone to the next.57 Their conclusion was based on ability of the Cu-loaded chaperone CCS to donate Cu into apo-SOD1 even in the presence of bathocurproine sulfate, a strong CuI chelator. Using thermodynamic binding constants, they estimated that there is < 1 aqueous Cu ion per cell. They rationalized that the intracellular milieu must have a large capacity for binding aqueous Cu ions, and that aqueous Cu would be dangerous to the cell, due to its tendency to engage in Fenton chemistry. To the limited extent that our results can detect aqueous Cu (down to ~ 300 Cu ions/cell), they support the conclusion that there are no “free”/aqueous Cu ions in the mouse brain.

Similar thermodynamic calculations involving aqueous Zn ions in the cell yield concentrations of tens to hundreds of pM. Like Cu, this translates into < 1 aqueous Zn ion per cell assuming a cell volume of 10−14 L. Aqueous Zn ions also inhibit human receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase in accordance with KI = 21 ± 7 pM,58 again suggesting very few if any intracellular aqueous Zn ions. Our results suggest the absence of aqueous Zn in the mouse brain and provide substantial evidence for protein-based Zn complexes. We propose that the Zn species released during the firing of synaptic vesicles have one or more non-aqueous ligands. The species released are almost certainly not “free”/aqueous Zn.

Aqueous metal ions rapidly exchange bound waters with the solvent, with rate-constants that vary in the order NiII < CoII < FeII < MnII < ZnII < CuII.59 The waters on such complexes have average residence times ranging from 10−4 – 10−10 sec. At moments when a coordinated water dissociates, thousands of potential ligands in the cellular milieu could interact with the metal at the vacant coordination site. This would promote the formation of a new complex. In the likely event that the new ligand would coordinate stronger than water, the complex would become less dynamic. Even if no permanent complexes formed, the result of this dynamic exchange-reaction would be a population-distribution of closely related and rapidly interconverting species rather than a single entity. Indeed the broad structured peaks obtained from the chromatographic migration of aqueous metal ions in our study suggest such a population of species. Could such dynamical populations serve discrete physiological functions in a cell, or would they be deleterious, engaging in uncontrolled side reactions that produce toxic species? We suspect that cells could not survive the uncontrollable behavior of most aqueous transition metal ions. Moreover, the cell would be unable to regulate such ions since the coordinating ligands would not be under genetic control. Chaos would result.

Accordingly, aqueous metal ions with the fastest water exchange-dynamics would seem to be the least likely to exist in a cell, while those with slower exchange-dynamics might be sufficiently stable. Our detection of aqueous Co ions in FTSs supports this possibility, since, of the metals examined, aqueous CoII exchanges water ligands slowest. To test this idea further, aqueous NiII ions, which exhibit even slower water exchange-dynamics, were added to a FTS prior to passage through the column. A single peak with the MM of aqueous NiII was detected. When other aqueous metal ions, including Fe, Cu, Zn and Mn were added to the FTS, the only aqueous ion detected in the resulting chromatograms was Co (data not shown). Alternatively, or in addition, our detection of aqueous Co may be arise from the greater sensitivity of Co relative to the other metals.

The fast ligand exchange-dynamics inherent to metal ions are slowed with polydentate ligands. Polydentate metal complexes would likely exist as single autonomous entities that are not in a dynamic equilibrium with other potential ligands in the cell. Slower exchange dynamics would minimize toxic side reactions because they would not have dynamically-free sites. Moreover, such ligands would need to be synthesized and thus regulated by the cell. The shape of such large complexes would allow other cellular components (e.g. membrane-bound protein transporters) to recognize and distinguish one complex from another. All of these factors favor the occurrence in the cell of metal complexes with polydentate ligands. Undoubtedly all of the LMM metal complexes characterized in this study are of that type.

We are particularly interested in metal complexes involved in metal ion trafficking – assuming such complexes exist. For such complexes, the coordinating polydentate ligands must bind strong enough to avoid the problems mentioned above, yet also allow the metal to be transferred to downstream acceptors. In some well-documented cases, altering the redox state of the metal60 or the pH61 of the solution are sufficient to labilize the ligands. Binding to a protein or macromolecular complex might also labilize the ligands coordinating a metal. One future task will be to identify the complexes and the LMM metal-containing proteins that we have detected here.

Determining the physiological role of each LMM metal complex in the brain that we have described in this study will be a challenge that will require multiple “orthogonal” approaches. The LC-ICP-MS approach used here is complementary to that of treating cells or tissues with custom-designed chelators that react with and sense labile metal complexes.12, 25, 26, 41 The advantage of the chelator-based method is the ability to detect labile metal ions in intact live cells. The disadvantages are that such chelators may react with multiple species in the cell, and that the process of detection destroys the complexes of interest. The advantage of the LC-ICP-MS approach is that individual metal complexes can be detected undisturbed (barring potential degradation reactions occurring during workup). The disadvantage is that the cell itself must be disrupted such that critical information regarding cellular compartmentalization is lost. Merging these approaches, e.g. using LC-ICP-MS to assess which particular complexes react with designer metal sensors, will undoubtedly yield the greatest insight into metal ion metabolism in cells and super-cellular structures such as the brain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Russ Hille (University of California, Riverside) for the xanthine oxidase sample and advice on cofactor isolation, and Louise Abbott (Texas A&M University) for help with animal handling. This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health (GM084266) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (A1170).

Abbreviation

- AD

Alzheimer’s Disease

- CV

column volume

- FTS

flow-through solution

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

glutathione disulfide

- HMM

high molecular mass

- ICP-MS

inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer

- IMM

intermediate molecular mass

- IP6

inositol hexaphosphate

- LIP

labile iron pool

- LMM

low molecular mass

- MM

molecular mass

- NHHS

nonheme high-spin

- PD

Parkinson’s Disease

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TMG

Trace metal grade

- Ve

elution volume

- V0

void volume

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Fig. S1, calibration curve for determining MMs; Table S1, compounds used for calibrating the size-exclusion column; Table S2, concentrations of LMM metal ions in the brain; Fig. S2 – S9, individual chromatograms obtained for the following elements, including Fig. S2, P; Fig. S3, S; Fig. S4; Co; Fig. S5, Cu; Fig. S6, Zn; Fig. S7, Fe; Fig. S8, Mn; Fig. S9, Mo; Fig. S10, chromatograms obtained while testing for sample degradation; Fig. S11, chromatograms obtained using different buffers; Table S3, cellular metal ion limits of detection using the insturment. Fig. S12, closeup of minor chromatographic peaks.

Notes and references

- 1.Valko M, Rhodes CJ, Moncol J, Izakovic M, Mazur M. Chem-Biol Interact. 2006;160:1–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galaris D, Pantopoulos K. Crit Rev Cl Lab Sci. 2008;45:1–23. doi: 10.1080/10408360701713104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ba LA, Doering M, Burkholz T, Jacob C. Metallomics. 2009;1:292–311. doi: 10.1039/b904533c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crichton RR, Wilmet S, Legssyer R, Ward RJ. J Inorg Biochem. 2002;91:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(02)00461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moos T, Morgan EH. Ann Ny Acad Sci. 2004;1012:14–26. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes-Hampton GP, Chakrabarti M, Cockrell AL, McCormick SP, Abbott LC, Lindahl LS, Lindahl PA. Metallomics. 2012;4:761–770. doi: 10.1039/c2mt20086d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finney LA, O’Halloran TV. Science. 2003;300:931–936. doi: 10.1126/science.1085049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muhlenhoff U, Stadler JA, Richhardt N, Seubert A, Eickhorst T, Schweyen RJ, Lill R, Wiesenberger G. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40612–40620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pamp K, Kerkweg U, Korth HG, Homann F, Rauen U, Sustmann R, de Groot H, Petrat F. Biochimie. 2008;90:1591–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jhurry ND, Chakrabarti M, McCormick SP, Holmes-Hampton GP, Lindahl PA. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5276–5284. doi: 10.1021/bi300382d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrat F, de Groot H, Rauen U. Biochem J. 2001;356:61–69. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3560061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rauen U, Springer A, Weisheit D, Petrat F, Korth HG, de Groot H, Sustmann R. Chembiochem. 2007;8:341–352. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrat F, de Groot H, Sustmann R, Rauen U. Biol Chem. 2002;383:489–502. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes-Hampton GP, Miao R, Morales JG, Guo YS, Münck E, Lindahl PA. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4227–4234. doi: 10.1021/bi1001823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandey A, Yoon H, Lyver ER, Dancis A, Pain D. Mitochondrion. 2012;12:539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2012.07.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaur D, Rajagopalan S, Andersen JK. Brain Res. 2009;1297:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wypijewska A, Galazka-Friedman J, Bauminger ER, Wszolek ZK, Schweitzer KJ, Dickson DW, Jaklewicz A, Elbaum D, Friedman A. Parkinsonism Relat D. 2010;16:329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sohal RS, Wennberg-Kirch E, Jaiswal K, Kwong LK, Forster MJ. Free Radical Bio Med. 1999;27:287–293. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magaki S, Mueller C, Yellon SM, Fox J, Kim J, Snissarenko E, Chin V, Ghosh MC, Kirsch WM. Brain Res. 2007;1158:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meguro R, Asano Y, Odagiri S, Li CT, Shoumura K. Arch Histol Cytol. 2008;71:205–222. doi: 10.1679/aohc.71.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang K, Li HX, Shen H, Li M. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2012;146:79–85. doi: 10.1007/s12011-011-9230-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bitanihirwe BKY, Cunningham MG. Synapse. 2009;63:1029–1049. doi: 10.1002/syn.20683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palumaa P, Eriste E, Njunkova O, Pokras L, Jornvall H, Sillard R. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6158–6163. doi: 10.1021/bi025664v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viles JH. Coord Chem Rev. 2012;256:2271–2284. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomat E, Lippard SJ. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dean KM, Qin Y, Palmer AE. BBA-Mol Cell Res. 2012;1823:1406–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dittmer PJ, Miranda JG, Gorski JA, Palmer AE. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16289–16297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900501200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qin Y, Dittmer PJ, Park JG, Jansen KB, Palmer AE. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7351–7356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015686108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levenson CW. Nutr Rev. 2005;63:122–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang CJ, Nolan EM, Jaworski J, Okamoto KI, Hayashi Y, Sheng M, Lippard SJ. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:6774–6779. doi: 10.1021/ic049293d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang Z, Lippard SJ. Method Enzymol. 2012;505:445–468. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-388448-0.00031-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JY, Kim JS, Byun HR, Palmiter RD, Koh JY. Brain Res. 2011;1418:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaetke LM, Chow CK. Toxicology. 2003;189:147–163. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng W, Monnot AD. Pharmacol Therapeut. 2012;133:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou B, Gitschier J. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7481–7486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kono S. Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13:1190–1199. doi: 10.2174/138945012802002320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carr HS, Winge DR. Accounts Chem Res. 2003;36:309–316. doi: 10.1021/ar0200807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Culotta VC, Strain J, Klomp LWJ, Casareno RLB, Gitlin JD. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:574–574. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stasser JP, Siluvai GS, Barry AN, Blackburn NJ. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11845–11856. doi: 10.1021/bi700566h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macreadie IG. Eur Biophys J Biophy. 2008;37:295–300. doi: 10.1007/s00249-007-0235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Domaille DW, Zeng L, Chang CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1194. doi: 10.1021/ja907778b. + [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirayama T, Van de Bittner GC, Gray LW, Lutsenko S, Chang CJ. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2228–2233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113729109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Culotta VC, Yang M, O’Halloran TV. BBA-Mol Cell Res. 2006;1763:747–758. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown DR. Metallomics. 2010;2:186–194. doi: 10.1039/b912601e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hille R, Nishino T, Bittner F. Coord Chem Rev. 2011;255:1179–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carmi-Nawi N, Malinger G, Mandel H, Ichida K, Lerman-Sagie T, Lev D. J Child Neurol. 2011;26:460–464. doi: 10.1177/0883073810383017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vijayakumar K, Gunny R, Grunewald S, Carr L, Chong KW, DeVile C, Robinson R, McSweeney N, Prabhakar P. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;45:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stangl GI, Schwarz FJ, Kirchgessner M. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1999;69:120–126. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.69.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalhan SC, Marczewski SE. Rev Endocr Metab Dis. 2012;13:109–119. doi: 10.1007/s11154-012-9215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dixon MM, Huang S, Matthews RG, Ludwig M. Structure. 1996;4:1263–1275. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matthews RG, Koutmos M, Datta S. Curr Opin Struc Biol. 2008;18:658–666. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cvetkovic A, Menon AL, Thorgersen MP, Scott JW, Poole FL, Jenney FE, Lancaster WA, Praissman JL, Shanmukh S, Vaccaro BJ, Trauger SA, Kalisiak E, Apon JV, Siuzdak G, Yannone SM, Tainer JA, Adams MWW. Nature. 2010;466:779–U18. doi: 10.1038/nature09265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deistung J, Bray RC. Biochem J. 1989;263:477–483. doi: 10.1042/bj2630477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Veiga N, Torres J, Mansell D, Freeman S, Dominguez S, Barker CJ, Diaz A, Kremer C. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2009;14:51–59. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bronowicka-Adamska P, Zagajewski J, Czubak J, Wrobel M. J Chromatogr B. 2011;879:2005–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhuang YL, Ma F, Li-Ling J, Xu XF, Li YD. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:1978–1985. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rae TD, Schmidt PJ, Pufahl RA, Culotta VC, O’Halloran TV. Science. 1999;284:805–808. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson M, Hogstrand C, Maret W. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:9322–9326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.320796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lincoln SF. Helv Chim Acta. 2005;88:523–545. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nunez MT, Gaete V, Watkins JA, Glass J. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6688–6692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sargent PJ, Farnaud S, Evans RW. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:2683–2693. doi: 10.2174/092986705774462969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.