Abstract

The study of complex heterodimeric peptide ligands has been hampered by a paucity of pharmacological tools. To facilitate such investigations, we have explored the utility of membrane tethered ligands (MTLs). Feasibility of this recombinant approach was explored with a focus on Drosophila bursicon, a heterodimeric cystine-knot protein that activates the G protein–coupled receptor rickets (rk). Rk/bursicon signaling is an evolutionarily conserved pathway in insects required for wing expansion, cuticle hardening, and melanization during development. We initially engineered two distinct MTL constructs, each composed of a type II transmembrane domain, a peptide linker, and a C terminal extracellular ligand that corresponded to either the α or β bursicon subunit. Coexpression of the two complementary bursicon MTLs triggered rk-mediated signaling in vitro. We were then able to generate functionally active bursicon MTLs in which the two subunits were fused into a single heterodimeric peptide, oriented as either α-β or β-α. Carboxy-terminal deletion of 32 amino acids in the β-α MTL construct resulted in loss of agonist activity. Coexpression of this construct with rk inhibited receptor-mediated signaling by soluble bursicon. We have thus generated membrane-anchored bursicon constructs that can activate or inhibit rk signaling. These probes can be used in future studies to explore the tissue and/or developmental stage-dependent effects of bursicon in the genetically tractable Drosophila model organism. In addition, our success in generating functionally diverse bursicon MTLs offers promise that such technology can be broadly applied to other complex ligands, including the family of mammalian cystine-knot proteins.

Introduction

The Drosophila receptor rickets (rk) is a member of the leucine-rich repeat containing subfamily of G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) (Van Loy et al., 2008). Rk activation is required for wing expansion, cuticle sclerotization, and melanization. The endogenous rk agonist, bursicon, is a heterodimeric cystine-knot protein. Bursicon has been known as the insect tanning hormone for more than four decades; however, only in 2005 was it discovered that the active ligand is composed of two unique subunits, bursicon (Bur α) and partner of bursicon (Bur β) (Luo et al., 2005; Mendive et al., 2005).

Rk/bursicon signaling is highly conserved among insects and has been shown to play an important role in development (Van Loy et al., 2007; Bai and Palli, 2010; Loveall and Deitcher, 2010). In Drosophila, bursicon is sequentially secreted from two distinct clusters of neuroendocrine cells shortly following eclosion. An initial wave of hormone is released from neurons in the subesophageal ganglion, which in turn induces secondary release of bursicon from another subset of neurons in the abdominal ganglion. This sequence ultimately triggers wing expansion, cuticle hardening, and pigmentation (Luan et al., 2006; Peabody et al., 2008). RNAi studies in Drosophila revealed that downregulation of rk during development compromises insect survival (Dietzl et al., 2007; Loveall and Deitcher, 2010). Although bursicon and rk signaling have been most extensively investigated in Drosophila, other studies have shown that this pathway is essential for viability of other insect species, including T. castaneum (Bai and Palli, 2010). Rk and bursicon-like sequences have been identified in a wide variety of insects, suggesting that the physiologic significance of this signaling cascade has been highly conserved (Van Loy et al., 2007; Honegger et al., 2008, 2011; An et al., 2009). The vast majority of research on rk/bursicon has focused on the functional role of this regulatory system during development. One limitation of these efforts stems from the paucity of pharmacological modulators of this GPCR that can be used as experimental tools.

Both bursicon subunits (Bur α and Bur β) are members of the eight-membered ring cystine-knot proteins. This family also includes the bone morphogenetic protein antagonists known to be required for development and organogenesis (Avsian-Kretchmer and Hsueh, 2004). Bursicon is also structurally related to the family of glycohormone cystine-knot proteins that activate leucine-rich repeat containing GPCRs. Corresponding mammalian GPCRs include the luteinizing hormone (LH), follicular-stimulating hormone (FSH), and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptors. The glycohormone ligands share a common α subunit, and each has a unique β subunit that confers receptor specificity (Hearn and Gomme, 2000). Comparison of bursicon and rk with LH, FSH, and TSH ligand/receptor pairs suggests that these structurally related hormones and GPCRs arose from common ancestors (Van Loy et al., 2008).

Generating pharmacological tools to probe the physiology of rk/bursicon in vivo presents considerable practical hurdles. For example, like mammalian glycohormones, bursicon is composed of two large and complex molecules. As a result, conventional peptide synthesis is impractical for making a functionally active ligand. In addition, introduction of mutations into corresponding recombinant DNA constructs aimed at expressing variant cystine-knot proteins in heterologous cell lines may be hampered by impaired processing and/or secretion of the peptide (Darling et al., 2000; Galet et al., 2009).

To circumvent these challenges, we have extended a strategy that our laboratory has previously used to study relatively short GPCR peptide ligands. Membrane tethered ligand (MTL) technology uses recombinant DNA to encode an extracellular peptide hormone fused to a linker sequence and a transmembrane domain. To date, a variety of short-peptide MTLs have been generated that selectively activate cognate class B GPCRs (Choi et al., 2009; Fortin et al., 2009, 2011). Previous investigations also demonstrated the utility of membrane tethered toxins as ion channel blockers (Auer and Ibanez-Tallon, 2010).

In the current report, we demonstrate that large, complex cystine-knot proteins that require a heterodimeric partner can be generated as functionally active MTLs. Furthermore, we use this extended MTL technology to identify a ligand domain that is required for rk receptor activation and to generate an inhibitor of rk signaling. In addition to providing insights into the structure function relationships underlying bursicon activity, respective constructs provide novel tools for further analysis of associated physiology in vivo. Extending from our current investigation, the approach developed for bursicon can be used to study related cystine-knot proteins (e.g., glycohormones, bone morphogenetic protein antagonists) as well as other complex peptide ligands.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville GA), 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (Life Technologies). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Plasmids.

The cDNA encoding rk, also known as Drosophila leucine-rich repeat containing GPCR 2 (dLGR2; GenBank: AF142343) was generously provided by Dr. Cornelis Grimmelikhuijzen, and subcloned into pcDNA1.1 using the restriction enzymes HindIII and XbaI (Eriksen et al., 2000). Bursicon α and β cDNAs in pcDNA3.1 were generously provided by Dr. J. Vanden Broeck (Mendive et al., 2005). The type II MTL backbone was generated by polymerase chain reaction amplification of the transmembrane domain (amino acids 10–56) of tumor necrosis factor α from a cDNA template (National Center for Biotechnology Information accession number BC028148) (Marmenout et al., 1985). The nucleotide and corresponding amino acid sequence of the type II construct is presented in Supplemental Fig. 1. The bursicon α and β subunits were subcloned by polymerase chain reaction into the type II MTL backbone. The bursicon MTL constructs included nucleotide sequences corresponding to amino acids 30–143 for Bur α and 21–141 for Bur β (Mendive et al., 2005). For the monomeric cherry fluorescent protein (CHE)–membrane tethered bursicon (tBur)–β-α construct, a cDNA encoding cherry fluorescent protein was ligated in frame 5′ of the tumor necrosis factor α transmembrane domain coding sequence to create an intracellular fluorescent tag.

The negative control MTL, CHE-tethered chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CHE-tCCL2) contains the same fluorescent tag and backbone as CHE-tBur-β-α, with the α and β subunits replaced by amino acids 25–99 of human chemokine ligand 2 (National Center for Biotechnology Information accession number NP_002973.1). All cAMP response element (6X-CRE) reporter genes and β-galactosidase plasmids were as previously described (Choi et al., 2009; Fortin et al., 2009).

Transfections.

Polyethylenimine (PEI) transfection reagent was prepared as previously described (Zaric et al., 2004). All transfections were performed using a final PEI concentration of 2 μg/ml. Transfections were performed in serum-free DMEM with antibiotics at 37°C. Cells were incubated with transfection mix for 20–48 hours, as indicated in the figure legends, prior to initiating functional or MTL expression assays.

Bursicon Conditioned Media.

HEK293 cells were seeded in 75 cm2 flasks at 1.2 million cells/flask. Twenty-four hours later, cells were cotransfected with 4 μg each of bursicon α and bursicon β cDNAs (or 4 μg of a chimeric α-β cDNA construct as indicated) with PEI as previously described. Following a 24-hour incubation, the transfection medium was aspirated, and 12 ml of serum-free DMEM with antibiotics was added. The medium was conditioned for 48 hours, then collected, centrifuged at 1600g for 5 minutes to remove cellular debris, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

Luciferase Assays.

Luciferase assays were performed as previously described (Hearn et al., 2002; Al-Fulaij et al., 2007; Fortin et al., 2009) with minor modifications. HEK293 cells at ∼80% confluence in 96-well plates were transiently transfected using PEI. To assess rk activity, each well was cotransfected with cDNAs encoding rk (0.25 ng), a luciferase reporter gene under the control of a cAMP response element (6X-CRE-Luc, 5 ng), bursicon constructs as indicated in the figure legends, and β-galactosidase as a transfection control (5 ng). To assess the function of tethered ligands, luciferase levels were quantified 24 hours after transfection using Steady-Light (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and normalized relative to β-galactosidase as previously described (Fortin et al., 2009). To assess the function of soluble ligands, bursicon-conditioned medium was added 20 hours after transfection for an additional 4-hour incubation. Luciferase and β-galactosidase levels were then measured as indicated earlier.

Confocal Microscopy.

HEK293 cells were transfected in 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (Mattek, Ashland, MA). Cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding rk, a cherry fluorescent protein tagged tBur-β-α construct, and a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene under the control of a cAMP response element (6X-CRE-GFP) (Fortin et al., 2011). After 48 hours, the cells were fixed for 10 minutes using 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were subsequently washed with PBS containing 100 mM glycine and then kept covered with PBS to prevent drying. Microscopy was performed on a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany) with an inverted 40× oil objective. Two channels were used to simultaneously monitor MTL expression (monomeric cherry fluorescent protein) and rk activation (GFP).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to quantify the expression of membrane tethered ligands. MTL encoding cDNAs were transfected into HEK293 cells grown in 96-well plates. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the medium was replaced with 50 μl of DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum with antibiotics; the cells were then grown for an additional 24 hours. Following this period, ELISA was performed as previously described (Fortin et al., 2009; Doyle et al., 2012) using a rabbit polyclonal myc proto-oncogene protein (c-myc) conjugated horseradish peroxidase antibody at 1:2500 dilution (AbCam, Cambridge, MA).

Programs and Statistics.

All luciferase and expression data were graphed and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). All cDNA sequences were analyzed using Vector NTI Advanced 9 software (Life Technologies).

Results

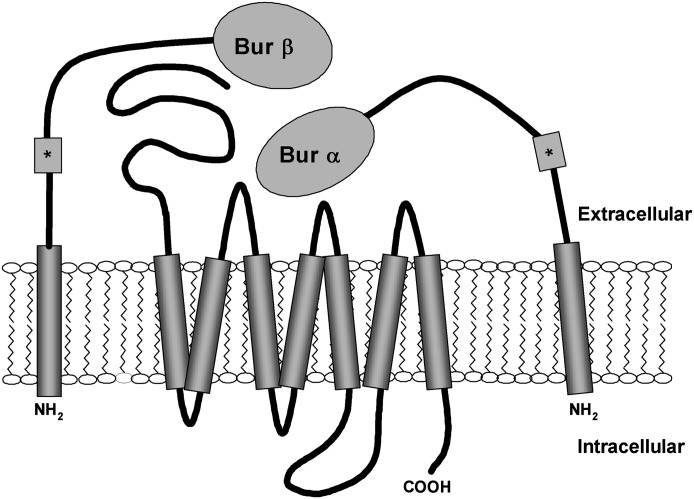

In this study, we explored the utility of MTLs as pharmacological tools for studying complex heterodimeric protein ligands. We applied this technology to bursicon and rickets as a prototypical ligand-receptor pair. As a first step, we generated two independent tethered constructs: one encoding the α subunit and the other encoding the β subunit of bursicon (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of heterodimeric membrane tethered bursicon subunits coexpressed with rk.*c-myc epitope tag

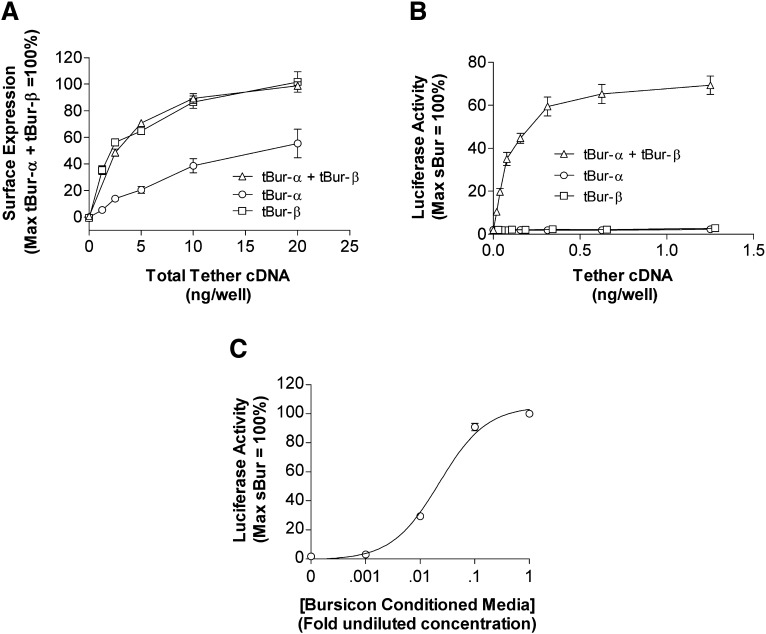

The design of these membrane tethered subunits included a type II transmembrane domain (TMD) with the intent of expressing the peptide ligand at the extracellular C terminus. Type II transmembrane domains specifically orient within the plasma membrane such that the N terminus is intracellular and the C terminus is extracellular. To verify the predicted orientation of the MTL, an ELISA directed at the extracellular c-myc epitope included in the construct was performed. In unpermeabilized HEK293 cells, both individually and coexpressed α and β subunit constructs were readily detected at the cell surface (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Bursicon membrane tethered α and β subunits together activate the Drosophila rickets receptor. (A) Quantification of cell surface expression of bursicon MTLs. Forty-eight hours after transfection, ELISA was performed using an antibody directed against a c-myc epitope. The x-axis denotes the total amount of cDNA transfected. (B) Tethered ligand-induced activation of rk-mediated signaling. HEK293 cells were transiently cotransfected with cDNAs encoding rk, a 6X-CRE-Luc reporter gene, one or both bursicon MTL subunit(s), and a β-galactosidase gene to control for transfection variability. For tethered ligand activity, 24 hours after transfection, luciferase activity was quantified and normalized relative to a 4-hour maximal stimulation of rk with bursicon-conditioned media. The x-axis denotes the amount transfected for each cDNA subunit. (C) Concentration-dependent activation of rk with bursicon-conditioned media. A series of 10-fold dilutions of conditioned media (1 = undiluted conditioned media) was added to cells 20 hours after transfection; the duration of ligand stimulation was 4 hours. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. tBur, bursicon MTL subunit cDNA.

We next examined ligand-induced signaling. Coexpression of cDNAs encoding both bursicon subunit MTLs together with rk and a 6X-CRE-Luc reporter gene led to concentration-dependent receptor activation (Fig. 2B). Coexpression of rk with each MTL alone (α or β) and a 6X-CRE-Luc reporter gene did not trigger signaling.

To quantify the magnitude of the signal obtained with coexpression of both bursicon MTLs, comparison was made relative to soluble bursicon (sBur). To enable these studies, we generated bursicon conditioned media by coexpressing both α and β subunit cDNAs (sBurα and sBurβ, respectively) in HEK293 cells and collecting the supernatant as detailed in Materials and Methods (Luo et al., 2005; Mendive et al., 2005). When conditioned medium was applied to rk-expressing cells, the resulting heterodimeric bursicon ligand triggered concentration-dependent luciferase reporter gene activity (Fig. 2C).

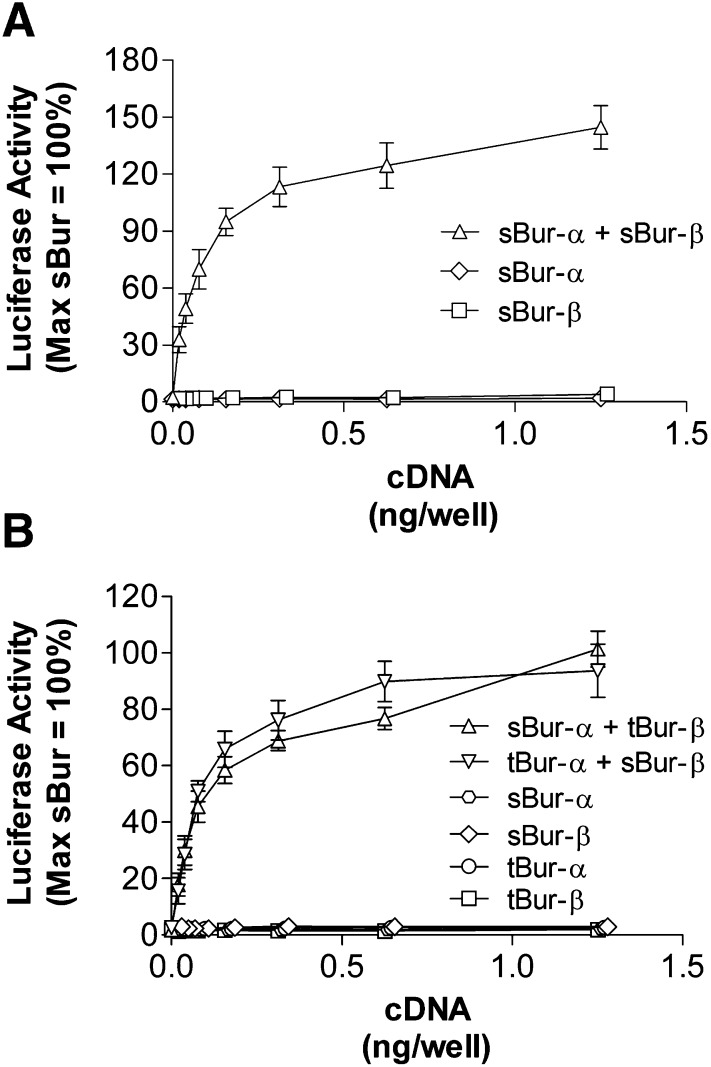

In parallel studies, we demonstrated that coexpression of freely soluble bursicon subunits in HEK293 cells together with rk and a 6X-CRE-Luc reporter gene also led to receptor-mediated signaling (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the known requirement of bursicon to form a heterodimer, expression of either subunit alone did not trigger receptor-mediated signaling.

Fig. 3.

Rk is activated by coexpression of either two complementary soluble bursicon subunits or complementary combinations of soluble and tethered bursicon subunits. HEK293 cells were transiently cotransfected with cDNAs encoding rk, a 6X-CRE-Luc reporter gene, and either soluble bursicon subunits (A) or combinations of soluble and tethered bursicon subunits (B). The x-axes denote the amount transfected for each cDNA subunit. Twenty-four hours following transfection, luciferase activity was quantified and activity values were normalized relative to maximal stimulation of rk with the addition of independently prepared bursicon-conditioned media. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. sBur, soluble Bursicon subunit cDNA; tBur, bursicon MTL subunit cDNA.

The previous studies set the stage to examine whether coexpression of one soluble (α or β) and one tethered ligand (β or α) would trigger receptor-mediated signaling. As shown in Fig. 3B, the soluble and tethered combinations were active. In contrast, when conditioned medium was generated from a single subunit cDNA (α or β) and added to cells expressing the complementary tethered subunit (β or α), no rk activation resulted (unpublished data).

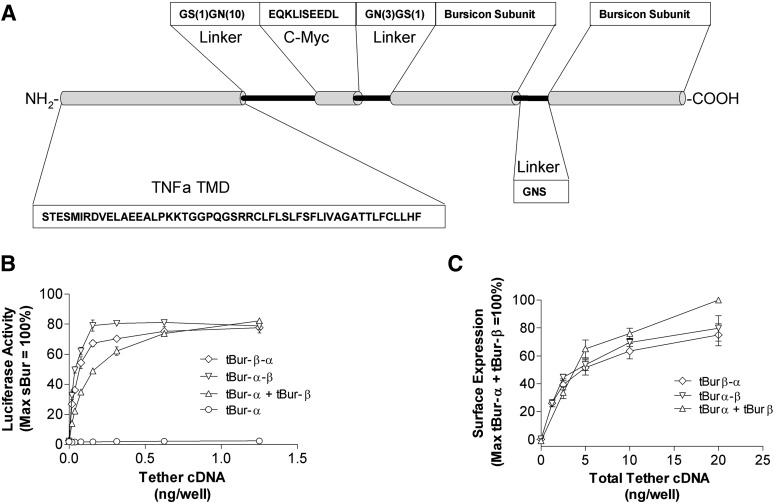

To further simplify a system for studying complex heterodimeric ligands, we explored the potential of membrane-tethered fusion proteins as functional ligands (Fig. 4A). The initial MTL β-α fusion protein that was generated positioned the α subunit at the construct’s free extracellular C terminus. When coexpressed with rk and the luciferase reporter gene, this MTL triggered GPCR-mediated signaling. A parallel construct with the opposite order of subunits (α-β, where the carboxy terminus of the β subunit was at the free extracellular end of the protein) also activated rk. Activity of each bursicon fusion protein MTL was similar regardless of orientation of the subunits. In addition, signaling by these MTLs was comparable to coexpression of tBur-α and tBur-β (Fig. 4B). Notably, expression levels of the fusion MTLs as assessed by ELISA were also comparable to the levels observed with single subunit constructs (Fig. 4C). These latter experiments confirmed, as observed with MTLs including a single bursicon subunit, that the ligand domains of tethered β-α and α-β are localized in the extracellular space. As an additional control, we demonstrated that conditioned media cannot be made from cells expressing either a heterodimeric fusion MTL or coexpressing individual subunit MTLs (Supplemental Fig. 3). This observation indicates that bursicon MTLs are not secreted.

Fig. 4.

Bursicon MTLs are active fusion proteins independent of C terminal subunit positioning. (A) Illustration of the protein structure of membrane-tethered constructs that include the two complementary bursicon subunits. (B) Tethered ligand–induced activation of rk-mediated signaling. HEK293 cells were transiently cotransfected with cDNAs encoding rk, a 6X-CRE-Luc reporter gene, the indicated bursicon MTL encoding construct(s), and a β-galactosidase control gene. Twenty-four hours after transfection, luciferase activity was quantified and normalized relative to maximal stimulation of rk with addition of bursicon-conditioned media. The x-axis denotes the amount transfected for each cDNA subunit. (C) Quantification of cell surface expression of bursicon MTLs. Forty-eight hours after transfection, ELISA was performed using an antibody directed against a c-myc epitope. The x-axis denotes the total amount of cDNA transfected. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. tBur, bursicon MTL subunit cDNA; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α.

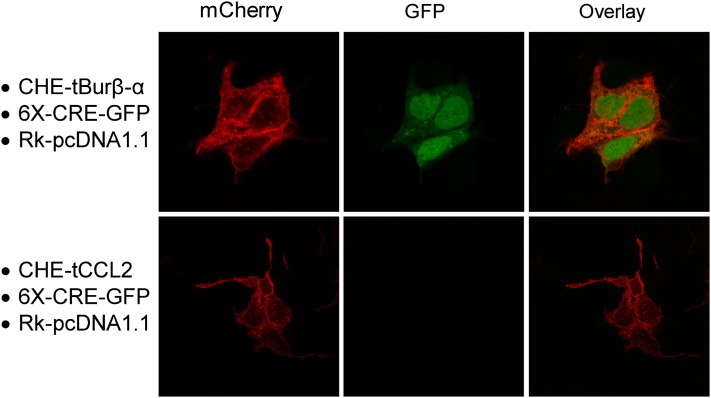

As a complementary index of tBur-β-α function (in addition to luciferase activity), we visually monitored ligand expression as well as MTL-induced signaling using a 6X-CRE-GFP reporter gene. To enable these studies, a tBur-β-α construct was generated that included a cherry fluorescent protein at the intracellular amino terminus (CHE-tBur-β-α). After cotransfection of cDNAs encoding CHE-tBur-β-α, rk, and a 6X-CRE-GFP reporter gene, MTL expression and receptor-mediated signaling could be simultaneously observed by confocal imaging. As shown in Fig. 5, CHE-tBur-β-α expression results in rk activation, triggering GFP production. In contrast, a nonspecific MTL CHE-tCCL2 [designed to activate the chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2] can be visualized at the cell surface, but does not trigger rk-mediated signaling (no 6X-CRE-GFP expression is induced).

Fig. 5.

Rk activation by a bursicon MTL fusion protein can be visually monitored by confocal microscopy. Representative images showing bursicon monomeric cherry (mCherry) fluorescent protein MTL triggering rk-mediated GFP expression. HEK293 cells were transiently cotransfected with cDNAs encoding CHE-tBurβ-α or CHE-tCCL2 (negative control), rk, and a 6X-CRE-GFP reporter gene. Confocal images were obtained 48 hours after transfection. Data represent three independent experiments.

In summary, our results with recombinant bursicon demonstrate that coexpression of both α and β subunits, either as two soluble peptides or as two independent membrane tethered constructs, is sufficient to generate active hormone. In addition, a single heterodimeric MTL with the peptide ligand in either the β-α or α-β configuration results in active bursicon. All bursicon MTLs appear to specifically activate rk (dLGR2). When tested on related Drosophila LGR receptors (dLGR1, dLGR3), no activation could be detected (Supplemental Fig. 4).

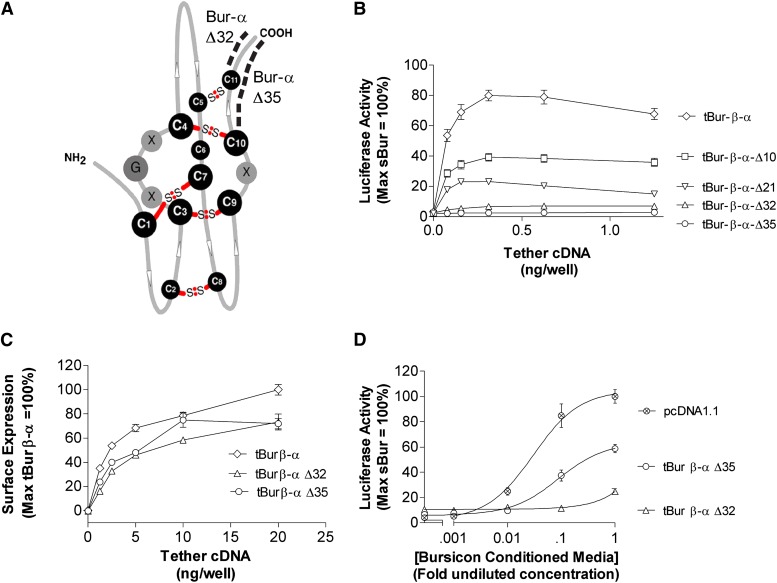

The ability to express recombinant functionally active bursicon heterodimers as a single MTL fusion protein enabled an expedited strategy for structure-function studies. As a first step, we examined the effect of serial deletions at the C terminus of the tBur-β-α construct (Fig. 6A). Deletion of 10, 21, 32, or 35 amino acids from the C terminus of tBur-β-α led to a progressive loss of MTL activity. The Δ10 and Δ21 constructs were partial agonists compared with full-length tBur-β-α. In contrast, little if any activation of rk was detected with expression of Δ32 and Δ35 MTLs (Fig. 6B). Deletion of the C terminus had little effect on cell surface expression levels (Fig. 6C). In contrast to the tBur-β-α constructs, corresponding deletions of the C terminus of tBur-α-β (up to or including the final cysteine residue) did not result in loss of agonist activity (Supplemental Fig. 5).

Fig. 6.

Development of a membrane tethered inhibitor of rk signaling. (A) Illustration of the secondary structure of the bursicon α subunit, a cystine-knot protein, highlighting the relative positions of deleted domains (dotted lines) [adapted from Fig. 2, Honegger et al. (2008)]. (B) Activity screen of bursicon MTL serial deletions. HEK293 cells were transiently cotransfected with cDNAs encoding rk, a 6X-CRE-Luc reporter gene, the indicated bursicon MTL, and a β-galactosidase control gene. Twenty-four hours after transfection, luciferase activity was quantified and normalized relative to maximal stimulation of rk after addition of bursicon-conditioned media. (C) Quantification of cell surface expression of full-length versus C terminally truncated bursicon MTLs. Forty-eight hours after transfection, ELISA was performed using an antibody directed against a c-myc epitope. (D) Expression of bursicon MTL C terminal deletion constructs disrupts receptor activation by soluble bursicon. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with 2 ng of the indicated MTL construct, rk, a 6X-CRE-Luc reporter gene, and a β-galactosidase control gene. Twenty hours following transfection, bursicon-conditioned medium was added at a series of 10-fold dilution (1 = undiluted conditioned media). Following a 4-hour incubation with bursicon conditioned media, luciferase activity was quantified and normalized relative to maximal stimulation of rk by bursicon-conditioned media in the absence of a tethered inhibitor. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. tBur, bursicon MTL subunit cDNA.

Further analysis of tBur-β-α Δ32 and Δ35 MTLs revealed these tethered constructs markedly inhibited receptor stimulation by soluble bursicon (conditioned media). Functional antagonism of tBur-β-α Δ35 was suggested by a significant rightward shift of the conditioned media concentration response curve when this construct was expressed (Fig. 6D). With the tBur-β-α Δ32, an even more pronounced inhibition resulted, essentially eliminating agonist-induced signaling.

Discussion

We have developed novel recombinant constructs that enable membrane-anchored expression of bioactive bursicon. Our study demonstrates that MTL technology can be applied to larger and considerably more complex GPCR ligands than those described in prior reports. Previously, only MTLs that included short peptide ligands (up to 39 amino acids) have been described (Choi et al., 2009; Fortin et al., 2009; Auer and Ibanez-Tallon, 2010; Fortin et al., 2011; Ibanez-Tallon and Nitabach, 2012). In contrast, the mature bursicon subunits, α and β, are 141 and 121 amino acids, respectively. Furthermore, each of these subunits is a cystine-knot protein that includes a series of intramolecular disulfide bridges which confer tertiary structure. As an additional prerequisite of agonist activity, the α and β subunits must interact to form a structurally integrated heterodimer (Mendive et al., 2005).

Given the stringent requirements underlying the formation of active soluble bursicon, including cellular coexpression, coprocessing, and cosecretion, the success in generating corresponding functional membrane tethered ligands could not have been anticipated. Initially, we demonstrated that expression of both single tethered bursicon subunits (α and β) in the same cell was sufficient to generate an active ligand. Follow-up studies revealed that coexpression of soluble and tethered complementary subunits also enabled the formation of active ligand. In contrast, when a single soluble subunit was added as conditioned media to cells expressing a tethered complementary subunit, no agonist activity was detectable (unpublished data). This finding suggests that intracellular assembly of the α-β heterodimer is a critical step in the formation of active hormone. These observations are consistent with reports on the heterodimerization requirements of soluble bursicon and other cystine-knot proteins that are known to undergo intracellular assembly prior to secretion as an active ligand (Xing et al., 2004). Remarkably, both membrane tethered and soluble bursicon subunits, despite the complexity of processing, appear to be fully compatible with each other in forming active heterodimers.

In an attempt to further understand the structural requirements underlying tethered bursicon function, we generated constructs in which both the α and β subunits were included in a single MTL. Since an active tethered ligand can be generated as either a β-α or α-β fusion construct, neither a free N nor a free C terminus is a requirement for agonist activity (Fig. 4B). It is noteworthy that conditioned medium containing a soluble form of the bursicon fusion protein tested in the β-α arrangement also shows agonist activity (Supplemental Fig. 6). Whether tethered or soluble, the bursicon fusions are active ligands. Our observations with bursicon reveal another parallel with mammalian heterodimeric cystine-knot proteins. Fusion of the α and β subunits of mammalian glycohormones including TSH, LH, and FSH as single soluble peptides also results in ligands that can activate their corresponding mammalian GPCR (Sugahara et al., 1996; Fares et al., 1998; Sen Gupta and Dighe, 2000; Park et al., 2005; Setlur and Dighe, 2007).

The generation of tethered bursicon fusion proteins provided a simplified model system to define domains of the dimer that are important for agonist activity (Fig. 6B). These experiments were guided by prior observations that the β subunit of mammalian glycohormones provides specificity and affinity for cognate receptors, whereas the α subunit is required for receptor activation (Park et al., 2005). Furthermore, the literature suggests that the C terminal domain of the glycohormone α subunit is an important determinant for ligand activity (Sato et al., 1997; Sen Gupta and Dighe, 2000; Butnev et al., 2002). Based on this knowledge, we generated a series of deletions in the C terminus of Burs α in the context of the tBur-β-α heterodimer. These experiments demonstrated that the C terminal domain in tethered bursicon was essential for rk activation. One of the deletion mutants in which 32 C terminal residues were truncated (designated as Δ32) not only led to loss of agonist activity, but also markedly inhibited the function of soluble bursicon (Fig. 6D). This observation suggests that, once a domain essential for agonist activity is removed in the corresponding MTL, the remaining truncated peptide can inhibit soluble agonist–induced signaling. However, an MTL with a larger C terminal deletion (Δ35), although also lacking agonist activity, was much less effective (versus Δ32) in blocking soluble bursicon–induced signaling. The difference between Δ32 and Δ35 is that three additional highly conserved residues including a critical cysteine are truncated in Δ35. The loss of these three residues may have compromised the tertiary structure of the tethered ligand, in turn explaining the functional difference in constructs. Soluble versions of the Δ32 and Δ35 constructs did not confer the same ability to block ligand-induced signaling (Supplemental Fig. 7). Thus, it is possible that membrane anchoring is required to generate a functional antagonist.

It is of note that the GPCR targeted MTLs that had been reported prior to this study all shared a common orientation, in which the peptide ligand was expressed with a free extracellular N terminus. In contrast, the bursicon MTLs were engineered with the opposite orientation (i.e., with a free extracellular carboxy terminus). This was achieved by incorporating a different transmembrane domain anchor (a type II TMD) into the construct. The ability to generate membrane-tethered ligands in either orientation markedly enhances the potential utility of MTL technology. For many peptides, orientation may be a critical factor in generating an active MTL. It is well established that, for peptide hormones recognizing class B GPCRs (e.g., secretin, parathyroid hormone, corticotropin releasing factor, glucagon-like peptide-1, gastric inhibitory polypeptide), the critical determinants of ligand efficacy reside in the N terminal domain of the hormone (Hoare, 2005). We have previously shown that each of these peptides remains active when incorporated into an MTL that includes a type I TMD, i.e., the extracellular free end of the peptide is the N terminus (Fortin et al., 2009). In contrast, peptide ligands recognizing class A GPCRs are more diverse. As examples, the amino termini of chemokines are generally considered critical for ligand activity, whereas for neuropeptides, functional determinants are often localized at the carboxyl terminus (Eipper and Mains, 1988; Mayer and Stone, 2001). In the latter case, it is anticipated that MTLs including a type II TMD will preserve biologic activity when corresponding peptides are anchored to the cell membrane.

In summary, we have developed a strategy that can be widely applied to the study of peptide ligands. More specifically, we have identified bursicon MTLs that either activate or block rk-mediated signaling. These findings set the stage for future in vivo studies. In the investigations to follow, we intend to selectively express tethered constructs in targeted tissues of Drosophila, thus exploring the utility of the approach for defining corresponding rk-mediated pathways/physiologies. Precedent with these bursicon MTLs will set the stage for parallel studies using other tethered cystine-knot proteins as tissue selective molecular probes. Candidate MTLs include mammalian glycohormones as well as non-GPCR regulators such as bone morphogenetic protein antagonists. The efficiency and flexibility of recombinant MTL technology will enable generation of a wide range of unique tools to complement the use of soluble ligands in understanding corresponding receptor-mediated physiologies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Isabelle Draper and Jamie Doyle for constructive suggestions throughout the course of this research.

Abbreviations

- CHE

monomeric cherry fluorescent protein

- CRE

cAMP response element

- dLGR1/2/3

Drosophila leucine-rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptors 1, 2 or 3

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FSH

follicular-stimulating hormone

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GPCR

G protein–coupled receptor

- HEK293

human embryonic kidney cells

- LH

luteinizing hormone

- MTL

membrane tethered ligand

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PEI

polyethylenimine

- rk

rickets

- sBur

soluble bursicon subunit cDNA

- tBur

bursicon MTL subunit cDNA

- TMD

transmembrane domain

- TSH

thyroid-stimulating hormone

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Harwood, Fortin, Kopin.

Conducted experiments: Harwood, Gao, Chen.

Performed data analysis: Harwood, Fortin, Beinborn, Kopin.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Harwood, Fortin, Beinborn, Kopin.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [Grant 5R01DK070155]. This work was also supported by the Synapse Neurobiology Training Program, National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Grant T32-NS061764].

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Al-Fulaij MA, Ren Y, Beinborn M, Kopin AS. (2007) Identification of amino acid determinants of dopamine 2 receptor synthetic agonist function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321:298–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An S, Wang S, Stanley D, Song Q. (2009) Identification of a novel bursicon-regulated transcriptional regulator, md13379, in the house fly Musca domestica. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 70:106–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer S, Ibañez-Tallon I. (2010) “The King is dead”: Checkmating ion channels with tethered toxins. Toxicon 56:1293–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avsian-Kretchmer O, Hsueh AJ. (2004) Comparative genomic analysis of the eight-membered ring cystine knot-containing bone morphogenetic protein antagonists. Mol Endocrinol 18:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai H, Palli SR. (2010) Functional characterization of bursicon receptor and genome-wide analysis for identification of genes affected by bursicon receptor RNAi. Dev Biol 344:248–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butnev VY, Singh V, Nguyen VT, Bousfield GR. (2002) Truncated equine LH beta and asparagine(56)-deglycosylated equine LH alpha combine to produce a potent FSH antagonist. J Endocrinol 172:545–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C, Fortin JP, McCarthy Ev, Oksman L, Kopin AS, Nitabach MN. (2009) Cellular dissection of circadian peptide signals with genetically encoded membrane-tethered ligands. Curr Biol 19:1167–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling RJ, Ruddon RW, Perini F, Bedows E. (2000) Cystine knot mutations affect the folding of the glycoprotein hormone alpha-subunit. Differential secretion and assembly of partially folded intermediates. J Biol Chem 275:15413–15421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzl G, Chen D, Schnorrer F, Su KC, Barinova Y, Fellner M, Gasser B, Kinsey K, Oppel S, Scheiblauer S, et al. (2007) A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature 448:151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JR, Fortin JP, Beinborn M, Kopin AS. (2012) Selected melanocortin 1 receptor single-nucleotide polymorphisms differentially alter multiple signaling pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 342:318–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eipper BA, Mains RE. (1988) Peptide alpha-amidation. Annu Rev Physiol 50:333–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen KK, Hauser F, Schiøtt M, Pedersen KM, Søndergaard L, Grimmelikhuijzen CJ. (2000) Molecular cloning, genomic organization, developmental regulation, and a knock-out mutant of a novel leu-rich repeats-containing G protein-coupled receptor (DLGR-2) from Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res 10:924–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares FA, Yamabe S, Ben-Menahem D, Pixley M, Hsueh AJ, Boime I. (1998) Conversion of thyrotropin heterodimer to a biologically active single-chain. Endocrinology 139:2459–2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin JP, Chinnapen D, Beinborn M, Lencer W, Kopin AS. (2011) Discovery of dual-action membrane-anchored modulators of incretin receptors. PLoS ONE 6:e24693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin JP, Zhu Y, Choi C, Beinborn M, Nitabach MN, Kopin AS. (2009) Membrane-tethered ligands are effective probes for exploring class B1 G protein-coupled receptor function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:8049–8054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galet C, Guillou F, Foulon-Gauze F, Combarnous Y, Chopineau M. (2009) The beta104-109 sequence is essential for the secretion of correctly folded single-chain beta alpha horse LH/CG and for its FSH activity. J Endocrinol 203:167–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearn MG, Ren Y, McBride EW, Reveillaud I, Beinborn M, Kopin AS. (2002) A Drosophila dopamine 2-like receptor: Molecular characterization and identification of multiple alternatively spliced variants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:14554–14559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearn MT, Gomme PT. (2000) Molecular architecture and biorecognition processes of the cystine knot protein superfamily: part I. The glycoprotein hormones. J Mol Recognit 13:223–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoare SR. (2005) Mechanisms of peptide and nonpeptide ligand binding to Class B G-protein-coupled receptors. Drug Discov Today 10:417–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honegger HW, Dewey EM, Ewer J. (2008) Bursicon, the tanning hormone of insects: recent advances following the discovery of its molecular identity. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol 194:989–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honegger HW, Estévez-Lao TY, Hillyer JF. (2011) Bursicon-expressing neurons undergo apoptosis after adult ecdysis in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. J Insect Physiol 57:1017–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibañez-Tallon I, Nitabach MN. (2012) Tethering toxins and peptide ligands for modulation of neuronal function. Curr Opin Neurobiol 22:72–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveall BJ, Deitcher DL. (2010) The essential role of bursicon during Drosophila development. BMC Dev Biol 10:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan H, Lemon WC, Peabody NC, Pohl JB, Zelensky PK, Wang D, Nitabach MN, Holmes TC, White BH. (2006) Functional dissection of a neuronal network required for cuticle tanning and wing expansion in Drosophila. J Neurosci 26:573–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo CW, Dewey EM, Sudo S, Ewer J, Hsu SY, Honegger HW, Hsueh AJ. (2005) Bursicon, the insect cuticle-hardening hormone, is a heterodimeric cystine knot protein that activates G protein-coupled receptor LGR2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:2820–2825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmenout A, Fransen L, Tavernier J, Van der Heyden J, Tizard R, Kawashima E, Shaw A, Johnson MJ, Semon D, Müller R, et al. (1985) Molecular cloning and expression of human tumor necrosis factor and comparison with mouse tumor necrosis factor. Eur J Biochem 152:515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer MR, Stone MJ. (2001) Identification of receptor binding and activation determinants in the N-terminal and N-loop regions of the CC chemokine eotaxin. J Biol Chem 276:13911–13916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendive FM, Van Loy T, Claeysen S, Poels J, Williamson M, Hauser F, Grimmelikhuijzen CJ, Vassart G, Vanden Broeck J. (2005) Drosophila molting neurohormone bursicon is a heterodimer and the natural agonist of the orphan receptor DLGR2. FEBS Lett 579:2171–2176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JI, Semyonov J, Chang CL, Hsu SY. (2005) Conservation of the heterodimeric glycoprotein hormone subunit family proteins and the LGR signaling system from nematodes to humans. Endocrine 26:267–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody NC, Diao F, Luan H, Wang H, Dewey EM, Honegger HW, White BH. (2008) Bursicon functions within the Drosophila CNS to modulate wing expansion behavior, hormone secretion, and cell death. J Neurosci 28:14379–14391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Perlas E, Ben-Menahem D, Kudo M, Pixley MR, Furuhashi M, Hsueh AJ, Boime I. (1997) Cystine knot of the gonadotropin alpha subunit is critical for intracellular behavior but not for in vitro biological activity. J Biol Chem 272:18098–18103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen Gupta C, Dighe RR. (2000) Biological activity of single chain chorionic gonadotropin, hCGalphabeta, is decreased upon deletion of five carboxyl terminal amino acids of the alpha subunit without affecting its receptor binding. J Mol Endocrinol 24:157–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlur SR, Dighe RR. (2007) Single chain human chorionic gonadotropin, hCGalphabeta: effects of mutations in the alpha subunit on structure and bioactivity. Glycoconj J 24:97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugahara T, Grootenhuis PD, Sato A, Kudo M, Ben-Menahem D, Pixley MR, Hsueh AJ, Boime I. (1996) Expression of biologically active fusion genes encoding the common alpha subunit and either the CG beta or FSH beta subunits: role of a linker sequence. Mol Cell Endocrinol 125:71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loy T, Van Hiel MB, Vandersmissen HP, Poels J, Mendive F, Vassart G, Vanden Broeck J. (2007) Evolutionary conservation of bursicon in the animal kingdom. Gen Comp Endocrinol 153:59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loy T, Vandersmissen HP, Van Hiel MB, Poels J, Verlinden H, Badisco L, Vassart G, Vanden Broeck J. (2008) Comparative genomics of leucine-rich repeats containing G protein-coupled receptors and their ligands. Gen Comp Endocrinol 155:14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y, Myers RV, Cao D, Lin W, Jiang M, Bernard MP, Moyle WR. (2004) Glycoprotein hormone assembly in the endoplasmic reticulum: IV. Probable mechanism of subunit docking and completion of assembly. J Biol Chem 279:35458–35468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaric V, Weltin D, Erbacher P, Remy JS, Behr JP, Stephan D. (2004) Effective polyethylenimine-mediated gene transfer into human endothelial cells. J Gene Med 6:176–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.