Abstract

Phase II conjugating enzymes play key roles in the metabolism of xenobiotics. In the present study, RNA sequencing was used to elucidate hepatic ontogeny and tissue distribution of mRNA expression of all major known Phase II enzymes, including enzymes involved in glucuronidation, sulfation, glutathione conjugation, acetylation, methylation, and amino acid conjugation, as well as enzymes for the synthesis of Phase II cosubstrates, in male C57BL/6J mice. Livers from male C57BL/6J mice were collected at 12 ages from prenatal to adulthood. Many of these Phase II enzymes were expressed at much higher levels in adult livers than in perinatal livers, such as Ugt1a6b, -2a3, -2b1, -2b5, -2b36, -3a1, and -3a2; Gsta1, -m1, -p1, -p2, and -z1; mGst1; Nat8; Comt; Nnmt; Baat; Ugdh; and Gclc. In contrast, hepatic mRNA expression of a few Phase II enzymes decreased during postnatal liver development, such as mGst2, mGst3, Gclm, and Mat2a. Hepatic expression of certain Phase II enzymes peaked during the adolescent stage, such as Ugt1a1, Sult1a1, Sult1c2, Sult1d1, Sult2as, Sult5a1, Tpmt, Glyat, Ugp2, and Mat1a. In adult mice, the total transcripts for Phase II enzymes were comparable in liver, kidney, and small intestine; however, individual Phase II enzymes displayed marked tissue specificity among the three organs. In conclusion, this study unveils for the first time developmental changes in mRNA abundance of all major known Phase II enzymes in mouse liver, as well as their tissue-specific expression in key drug-metabolizing organs. The age- and tissue-specific expression of Phase II enzymes indicate that the detoxification of xenobiotics is highly regulated by age and cell type.

Introduction

Liver, kidney, and intestine are the three major tissues involved in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of xenobiotics. Phase II conjugating enzymes, such as sulfotransferase (Sult), uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase (Ugt), glutathione S-transferases (Gst), N-acetyltransferase (Nat), catechol O-methyltransferase (Comt), and amino acid (AA) conjugation enzymes, play key roles in catalyzing the conjugation reaction of xenobiotics (Jancova et al., 2010). Phase II conjugates usually have decreased biologic activities. Moreover, products of most of these Phase II conjugation reactions, with the exception of methylation and acetylation, have markedly increased water solubility and are readily excreted from the body. Therefore, Phase II conjugation reactions are generally considered as major inactivation and detoxification pathways for xenobiotics, although activation of certain xenobiotics by these Phase II enzymes has been reported (Glatt, 2000; Regan et al., 2010). In addition to xenobiotics, Phase II enzymes are also important in the biotransformation of endobiotics, such as steroid hormones, thyroid hormones, bilirubin, and bile acids (Jancova et al., 2010).

Many drug-processing genes undergo marked changes in expression during tissue development and maturation. Children and newborn animals are often more susceptible to the adverse effects of therapeutic drugs and environmental chemicals due to their immature capacity to metabolize and detoxify these chemicals (Blake et al., 2005; Hines, 2008; Funk et al., 2012). Understanding of developmental changes in expression patterns of these Phase II enzymes will help to elucidate the mechanism of ontogenic regulation of gene expression. Additionally, extrahepatic tissues, including intestine and kidney, also play key roles in determining the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of xenobiotics (Krishna and Klotz, 1994). It is essential to understand the tissue-specific expression patterns of Phase II enzymes among the three major tissues in ADME, namely liver, kidney, and small intestine. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to elucidate ontogenic changes in mRNA expression of all major known Phase II enzymes during liver development and the distribution of mRNA expression of these Phase II enzymes in adult tissues of liver, kidney, and small intestine.

There is already some information about the ontogenic expression patterns and tissue distribution of certain Phase II enzymes in mice, such as Sult (Alnouti and Klaassen, 2006) and Gst enzymes (Knight et al., 2007; Cui et al., 2010). However, hepatic ontogenic changes in the mRNA expression of Ugt, Nat, methyltransferase, and AA-conjugating enzymes remain unknown. Moreover, conventional mRNA-profiling methods cannot compare the real abundance of transcripts between various genes. In contrast, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) provides a “true-quantification” of transcript counts (Malone and Oliver, 2011). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to use RNA-seq technology for the first time to generate comprehensive information on the ontogenic mRNA expression of all major known Phase II enzymes in liver, and the distribution of mRNAs of these genes in adult liver, kidney, and small intestine using mouse as a model in a quantitative mode. This information will provide a foundation for understanding the relative importance of various Phase II enzymes and their subfamily members in xenobiotic metabolism in liver at different developmental stages, as well as in the three key tissues of ADME, namely liver, kidney, and small intestine, in adulthood.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Eight-week-old C57BL/6J breeding pairs of mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). They were housed according to the American Animal Association Laboratory Animal Care guidelines, and were bred under standard conditions at the University of Kansas Medical Center. Livers from offspring were collected at the following 12 ages: days −2 (gestational day 17.5), 0 (right after birth and before the start of suckling), 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 45, and 60. Due to potential variations caused by the estrous cycle in maturing adult female mice, only male livers were used for this study (n = 3 per age, randomly selected from multiple litters). For the study of tissue distribution, tissues of liver, kidney, and small intestine were collected from adult male mice at 60 days of age (n = 2 per tissue). Tissues were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C before use.

Total RNA Preparation.

Total RNA from liver, kidney, and small intestine was isolated using RNAzol Bee reagent (Tel-Test Inc., Friendswood, TX) per the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentrations were quantified using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) at a wavelength of 260 nm. Integrity of the total RNA samples was evaluated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA), and the samples with RNA integrity values of >7.0 were used for the following experiments.

cDNA Library Preparation and RNA-Seq of Liver Ontogeny Samples.

The cDNA libraries from all total RNA samples of livers of 12 ages of mice were prepared using an Illumina TruSeq RNA sample prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Three micrograms of total RNA was used per the RNA input recommendations of the manufacturer’s protocol. The mRNAs were selected from the total RNAs by purifying the poly(A)-containing molecules using poly-T primers. The RNA fragmentation, first- and second-strand cDNA syntheses, end repair, adaptor ligation, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification were performed per the manufacturer’s protocol. Fragments of the cDNA library ranged from 220 to 500 basepair (bp), with an average size of 280 bp (including 100-bp adapter sequences). The quality of cDNA libraries was validated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer before sequencing by the Genome Sequencing Facility at the University of Kansas Medical Center. Briefly, the cDNA libraries were clustered onto a TruSeq paired-end flow cell and sequenced (2 × 100) using a TruSeq 200-cycle SBS kit (Illumina). For the initial run, a PhiX control (Illumina) was loaded on each flow cell as well as universal human reference RNA on 1 of the 16 lanes of the Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer, and sequenced in parallel with other samples to ensure the data generated for each run were accurately calibrated during the image analysis and data analysis. In addition, the PhiX was spiked into each cDNA sample at ∼1% as an internal quality control.

RNA-Seq Data Analysis.

After the sequencing platform generated the sequencing images, the pixel-level raw data collection, image analysis, and base calling were performed by the RTA (Real Time Analysis) software on a Dell PC attached to the HiSeq 2000 sequencer. The data were streamed off to the analysis server as the run was progressing. The BCL Converter converted the BCL (base calling) files to qseq files, and the qseq files were subsequently converted to FASTQ files for downstream analysis. The RNA-seq reads from the FASTQ files were mapped to the mouse reference genome (NCBI37/mm9), and the splice junctions were identified by TopHat. The output files in BAM (binary sequence alignment) format were analyzed by Cufflinks to estimate the transcript abundance. The transcript structure predictions of Cufflinks were compared with Ensembl GTF version 65 by Cuffcompare. RNA-seq generated an average of 175 million reads per sample, and >80% of the reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome (NCBI37/mm9) by TopHat (unpublished data). The mRNA abundance of genes was estimated by Cufflinks. The mRNA abundance was expressed in FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped), which normalizes sequencing depths between different samples and sizes between different genes, allowing direct comparison of expression levels among different transcripts on a genome-wide scale.

cDNA Library Preparation and RNA-Seq of Tissue Distribution Samples.

The preparation of cDNA libraries of adult male liver, kidney, and small intestine and sequencing of these cDNA libraries were conducted by Beijing Genomic Institute (Shenzhen, People’s Republic of China). Beads with oligo(dT) were used to isolate poly(A) mRNA from total RNA. Fragmentation buffer was added for breaking mRNA into short fragments. Taking these short fragments (200–700 nucleotides) as templates, random hexamer primers were used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA. The second-strand cDNA was synthesized using buffer, dNTPs, RNase H, and DNA polymerase I, respectively. Short fragments were purified with QiaQuick PCR extraction kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) and resolved with elution buffer for end reparation and adding poly(A). After that, the short fragments were connected with sequencing adaptors. For amplification with PCR, suitable fragments were selected as templates with respect to the result of agarose gel electrophoresis. The resultant cDNA libraries were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 2000. Images generated by sequencers were converted by base calling into nucleotide sequences, which were called raw reads and were stored in FASTQ format. After removal of poor-quality reads containing adapters, unknown, or low-quality bases from the raw reads, the resultant clean reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome (NCBI37/mm9) and the splice junctions were identified by TopHat. The FPKM method was used to calculate mRNA abundance, which normalizes sequencing depths between different samples and sizes between different genes. For the study of tissue distribution, the mRNA abundance was expressed as ratio to value of liver, with that of liver set as 1.0.

Validation of RNA-Seq Data with Real-Time PCR.

The total RNAs of male mouse livers at eight ages, days −2, 1, 5, 10, 20, 25, 45, and 60 (n = 3 per age), were reverse-transcribed into cDNAs using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The cDNAs were used for real-time PCR quantification of mRNA expression of mGst3 and Nat8 using the iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix and a MyiQ2 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). No single commonly used housekeeping gene had consistent mRNA expression levels throughout liver development (RNA-seq data, not shown). In contrast, the average expression levels of two housekeeping genes, namely Gapdh and Ncu-g1 (an integral membrane protein of the lysosome), were found to be consistent throughout liver development (Lu et al., 2012). Thus, amounts of mRNAs were calculated using the comparative computed tomography method, which determines the amount of target normalized to the geometric mean of Gapdh and Ncu-g1. Real-time PCR primers for mGst3 and Nat8 were: mGst3_for, AGATGGCTGTCCTCTCTAAGG; mGst3_rev, ATATGCCCGTTCTCAGGATCT; Nat8_for, GGACTACAAACAGGTCGTGGA; Nat8_rev, GCATACAACAGCCAGGAACCA.

Statistics.

Data are presented as mean ± S.E. Differences between various groups were determined using analysis of variance followed by post hoc test, with significance set at P ≤ 0.05. In the study of liver ontogeny, the FPKM values were log2-transformed to achieve normal distribution prior to analysis of variance. The statistics for mRNA expression of Phase II enzymes during liver development (RNA-seq data) are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Hierarchical clustering of Phase II conjugating enzymes was performed using Matlab (R2012b; The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA). The data were standardized to have a zero mean and unit variance at a gene level before clustering. The Ward's method was used for the linkage function applied on a Euclidean distance matrix of pairwise distances of gene expression.

Gene set enrichment analysis was carried out using Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA). IPA identifies significant networks, functions, canonical pathways, and associated transcription factors in a set of genes based on information gathered in the Ingenuity Pathway Knowledge Base (IPKB). The IPKB is an extensive repository of information on genes and gene products that interact with each other. The significance (P value) of the identified networks, functions, and canonical pathways was calculated using the right-tailed Fisher’s exact test. This test measures the significance of the overlap between the input genes and the genes in a particular category in the IPKB, reflecting the statistical significance of the network, function, or canonical pathway with respect to the input genes and the reference genes (all genes in the IPKB identified with the particular network, function, or canonical pathway). The analysis was performed on 85 Phase II genes. The selection criteria for an expressed gene were expression in at least one day measured by the presence of an FPKM value of ≥1.0. Input genes for “gene set enrichment” were perinatal Phase II genes (13 mapped and analyzed in IPA out of 13 in cluster), adolescent Phase II genes (14 mapped and analyzed in IPA out of 18 in cluster), and adult Phase II genes (46 mapped and analyzed in IPA out of 54 in cluster).

Results

The total FPKM values of all mRNA transcripts determined by RNA-seq were very similar among livers from different ages of mice and/or among the three adult mouse tissues of liver, kidney, and small intestine, which is consistent with the equal loading of total RNAs from these samples in RNA-seq. The RNA-seq data on ontogenic mRNA expression in livers of C57BL/6J mice were highly quantitative, which had been validated in our previous studies (Cui et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2012). The raw data of FPKM values of RNA-seq data presented in this study are listed in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3.

Total Expression and Proportions of Individual Phase II Enzymes during Liver Development in Male C57BL/6J Mice.

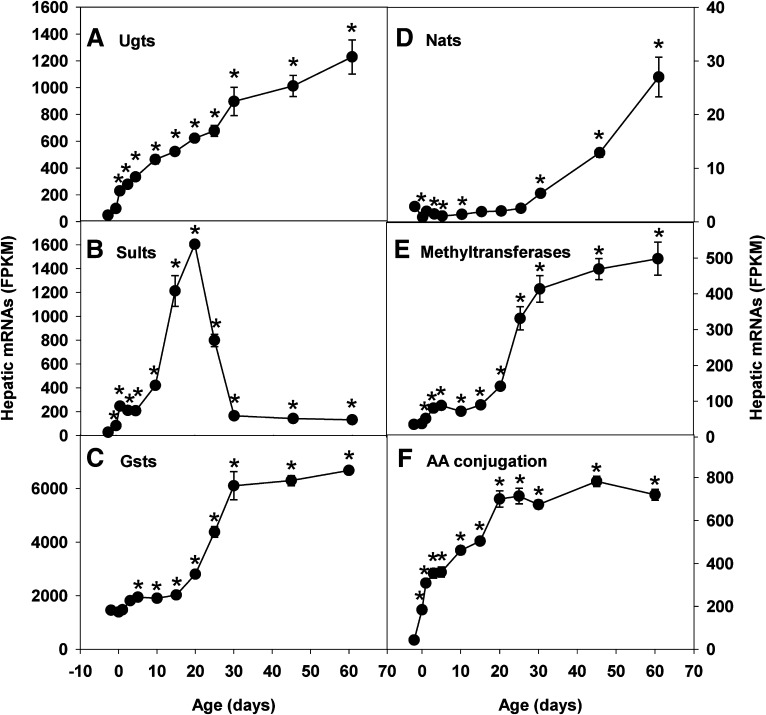

mRNA expression of most Phase II enzymes had marked ontogenic changes during liver development (Fig. 1). Total transcripts of Ugt enzymes in liver were low before birth, increased gradually after birth, and reached the highest levels of ∼24-fold prenatal levels 60 days after birth (Fig. 1A). Conversely, total transcripts of Sult enzymes in liver were low before birth, increased rapidly after birth, peaked at 20 days postbirth, and gradually fell back to ∼5-fold prenatal levels 60 days after birth (Fig. 1B). In contrast to the low prenatal expression of Ugt and Sult enzymes, total transcripts of Gst enzymes in liver were already high before birth, further increased gradually after birth, and plateaued at ∼4-fold prenatal levels 30 days after birth (Fig. 1C). Total transcripts of Nat enzymes (Nat1, -2, and -8) in liver were low before birth, slightly increased during postnatal development, started to surge after day 25 (weaning), and reached the highest levels at adulthood (day 60) (Fig. 1D). Compared with Nat enzymes, total transcripts of methyltransferases in liver were more abundant, and the postnatal surge started at the earlier time of day 20 (before weaning), reached high levels at day 30, and only increased slightly thereafter (Fig. 1E). Hepatic total transcripts of enzymes involved in AA conjugation of xenobiotics were low before birth, rapidly increased during perinatal stages, and reached adult levels after weaning (day 25) (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Hepatic ontogeny of total transcripts of Phase II enzymes in male C57BL/6J mice. Livers from C57BL/6J mice of ages −2 to 60 days were used for RNA-seq quantification of (A) Ugt, (B) Sult, (C) Gst, (D) Nat, (E) methyltransferase, and (F) AA conjugation enzymes. The y-axis represents mRNAs expressed as FPKM. n = 3, mean ± S.E. *P < 0.05 vs. day −2.

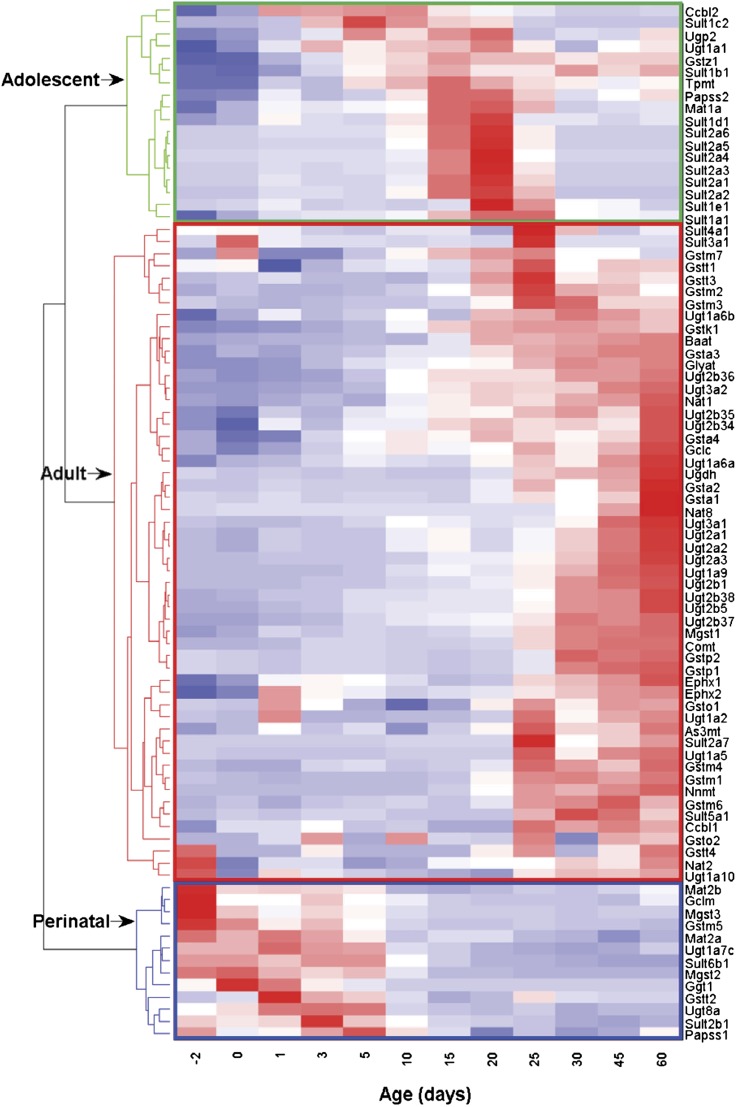

Hierarchical clustering revealed three distinct patterns of expression of Phase II conjugating enzymes in liver with age (Fig. 2). Of the 87 enzymes involved in Phase II conjugation, 84 genes were significantly expressed during different stages of liver development. The first cluster consisting of 13 genes was maximally expressed between prenatal day 2 (day −2) and postnatal day 5, and thus was categorized as perinatal-predominant Phase II conjugating enzymes. The second cluster of 18 genes, whose expression was maximal between day 5 and day 25, was categorized as adolescent-predominant Phase II conjugating enzymes. The third cluster of 53 genes, with maximum expression between day 25 and day 60, was identified as adult-predominant Phase II conjugating enzymes. It was observed that genes in different groups of Phase II conjugating enzymes were very selectively distributed among these three clusters (χ2 test of independence; Yates' P value, 0.0032). For example, of the perinatal-predominant genes, 62% were equally distributed at 4 genes (31%) each between Gst and cosubstrate-synthesizing enzymes. A majority of the adolescent-predominant genes were Sult genes (11 genes, 61%). Adult-predominant genes were mainly Gst (19 genes, 35%) and Ugt genes (18 genes, 33%).

Fig. 2.

Hierarchical clustering of hepatic ontogeny of Phase II conjugating enzymes in male C57BL/6J mice. Livers from C57BL/6J mice of ages −2 to 60 days were used for RNA-seq quantification. The two trees describe the relationship between different gene expression profiles (right tree) and various ages (bottom tree). The dendrogram scale represents the correlation distances. Average FPKM values of three replicates per age are given by colored squares: red, relatively high expression; blue, relatively low expression. The solid lines separate the expression profiles into three groups of perinatal-, adolescent-, and adult-predominant expression.

Among the main biologic functions significantly associated with the perinatal-predominant Phase II conjugating enzymes are metabolism of peptide, metabolism of glutathione (GSH), synthesis of GSH, synthesis of S-adenosylmethionine, and cholestasis. Genes associated with adolescent-predominant Phase II conjugating enzymes show significant function in sulfation of raloxifene, hormone, dopamine, 2-hydroxyestradiol, and β-estradiol; metabolism of estrogen; and steroid metabolism. The significant biologic functions ascribed to the adult-predominant Phase II conjugating enzymes include metabolism of xenobiotics, conjugation of GSH, glucuronidation of hormone, glucuronidation of estrogen, metabolism of GSH, glucuronidation of coumarin, conjugation of lipid, metabolism of peptide, glucuronidation of alcohol, etc.

Hepatic Ontogeny of Ugt mRNAs in Male C57BL/6J Mice.

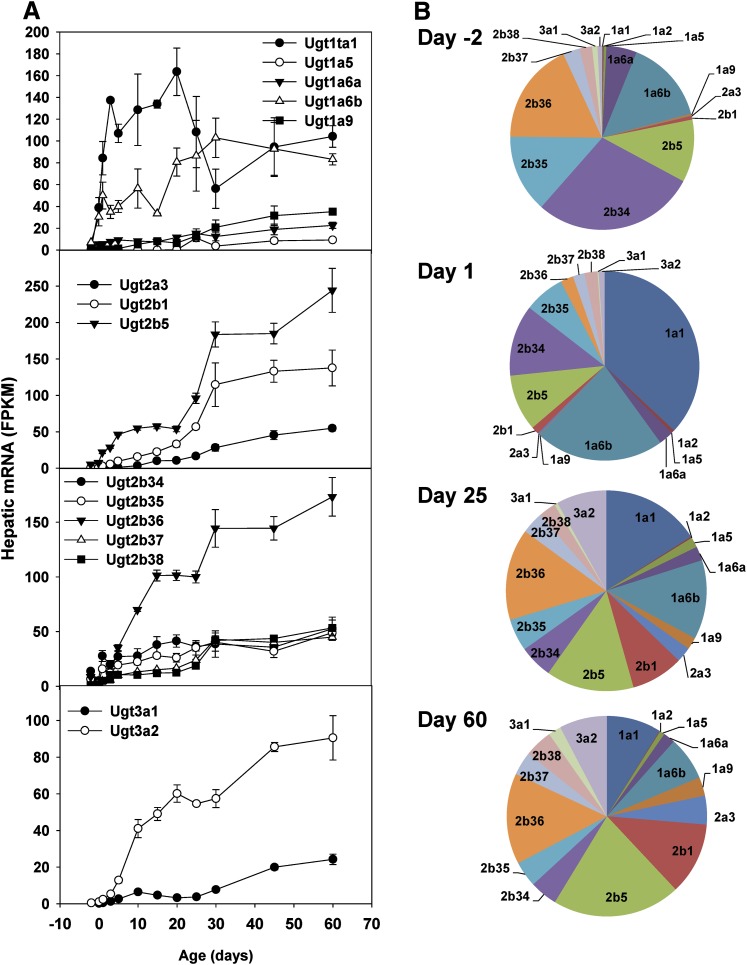

Glucuronidation is critical for the metabolism and excretion of endogenous compounds and xenobiotics. The vast majority of Ugt family members displayed the adult-predominant expression pattern, with low expression before birth and gradual postnatal increase to the highest in adulthood (Fig. 3). A prominent change was a marked postnatal surge in hepatic expression of Ugt1a1, which peaked during the adolescent stage and then decreased moderately at adulthood (Fig. 3A). In contrast, other Ugt1a subfamily members, including Ugt1a5, Ugt1a6a, Ugt1a6b, and Ugt1a9, all displayed the adult-predominant expression pattern (Fig. 3A). Among the Ugt2a subfamily, Ugt2a3, which catalyzes the glucuronidation of simple polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Bushey et al., 2013), had an adult-predominant expression pattern (Fig. 3A), whereas Ugt2a1 and Ugt2a2 were undetectable throughout liver development (unpublished data). All seven Ugt2b subfamily members, namely Ugt2b1, -2b5, -2b34, -2b35, -2b36, -2b37, and -2b38, had adult-predominant expression patterns (Fig. 3A). UGT3A1 is a UDP-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase with broad substrate activity toward ursodeoxycholic acid, 17α-estradiol, 17β-estradiol, and the prototypic substrates of the UGT1 and UGT2 forms, 4-nitrophenol and 1-naphthol (Mackenzie et al., 2008). In contrast, UGT3A2 uses UDP-glucose and UDP-xylose but not UDP-N-acetylglucosamine to glycosidate a broad range of substrates, including 4-methylumbelliferone, 1-hydroxypyrene, bioflavones, and estrogens (MacKenzie et al., 2011). Hepatic mRNA expression of Ugt3a1 and Ugt3a2 was very low before birth, increased gradually during postnatal development, and reached the highest levels at adulthood (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Hepatic ontogeny of Ugt mRNAs in male C57BL/6J mice. Livers from C57BL/6J mice of ages −2 to 60 days were used for RNA-seq quantification. (A) The y-axis represents mRNAs expressed as FPKM. n = 3, mean ± S.E. (B) Pie charts representing relative mRNA expression of each Ugt isoform as the percentage of total Ugt transcripts.

On day −2 (2 days before birth), Ugt2b34 was the most abundant Ugt isoform, followed by Ugt2b35, -2b36, -1a6b, and -2b5; Ugt1a1 only accounted for a very small percentage of total Ugts (Fig. 3B). On day 1 (neonatal stage), due to a marked surge in Ugt1a1 expression, Ugt1a1 became the most abundant Ugt isoform, followed by Ugt1a6b, -2b34, -2b35, and -2b5. On day 25 (adolescent stage), due to marked increases in the expression of Ugt2b family members, Ugt2b36 was the most abundant Ugt isoform, followed by Ugt1a1, -2b5, and -1a6b. On day 60 (adulthood), Ugt2b family members, namely Ugt2b5, -2b36, and -2b1, were the most abundant Ugt isoforms; however, many other Ugt1a, -2a, and -3a family members were also expressed at appreciable levels in adult liver (Fig. 3B). Ugt8a, a UDP-galactose:ceramide galactosyltransferase, was not expressed at any time during liver development (unpublished data).

Hepatic Ontogeny of Sult mRNAs in Male C57BL/6J Mice.

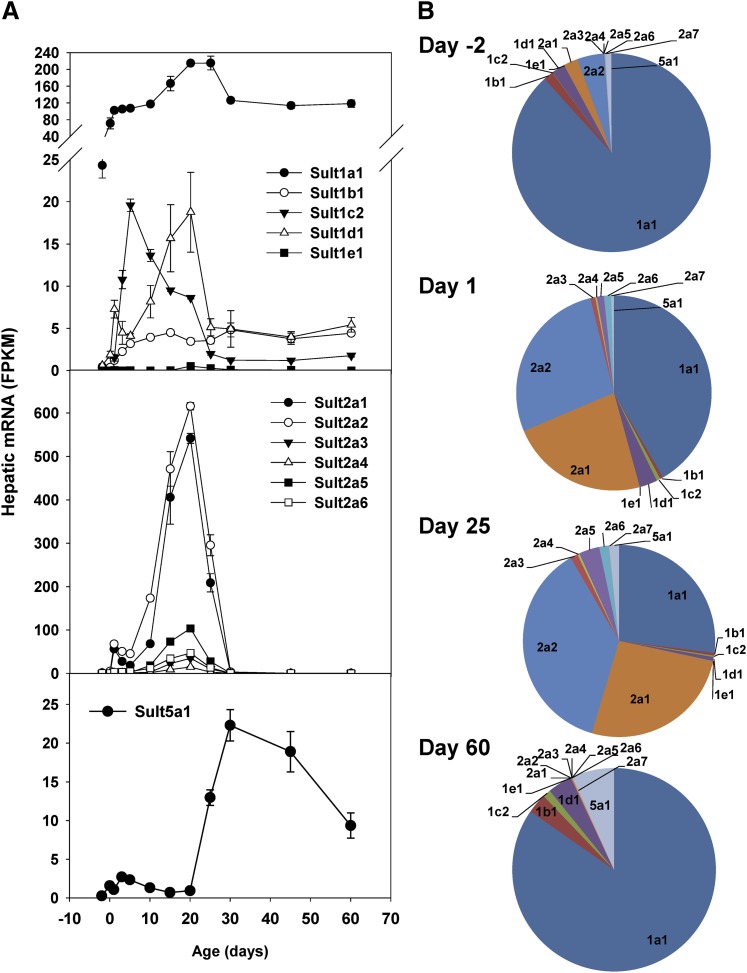

Sult family members had diverse ontogenic expression patterns during liver development (Fig. 4). Sult1a1, -1d1, -1e1, -2a1 to -2a6, and -5a1 all displayed adolescent-predominant expression patterns (Fig. 4A). Hepatic mRNA expression of Sult1c2 increased rapidly after birth, peaking at 5 days after birth, and then sharply decreased to low levels at 30 days of age. In contrast, hepatic expression of Sult1b1, which sulfonates dopamine and thyroid hormones (Saeki et al., 1998), reached the highest levels 15 days after birth and fluctuated thereafter (Fig. 4A). Sult3a1, -4a1, and -6b1 transcripts remained undetectable throughout liver development in male mice (unpublished data).

Fig. 4.

Hepatic ontogeny of Sult mRNAs in male C57BL/6J mice. Livers from C57BL/6J mice of ages −2 to 60 days were used for RNA-seq quantification. (A) The y-axis represents mRNAs expressed as FPKM. n = 3, mean ± S.E. (B) Pie charts representing relative mRNA expression of each Sult isoform as the percentage of total Sult transcripts.

Before birth (day −2), Sult1a1, which sulfonates phenolic compounds, including steroid hormones, catecholamines, and phenolic drugs (Hempel et al., 2007), was the predominant Sult isoform in liver, accounting for >80% of total Sult transcripts (Fig. 4B). On day 1, there were marked increases in the expression of steroid/bile acid sulfotransferase Sult2a (Huang et al., 2010) subfamily members, which account for >50% of total Sult transcripts in liver. A similar distribution in Sult isoforms was observed on day 25, but with a shrinking share for the Sult1 family members. On day 60, due to the silencing of most Sult2a subfamily genes, Sult1a1 resumed as the predominant Sult isoform in liver, accounting for >80% of total Sult transcripts, followed by Sult5a1, -1d1, and -1b1 (Fig. 4B).

Hepatic Ontogeny of Gst mRNAs in Male C57BL/6J Mice.

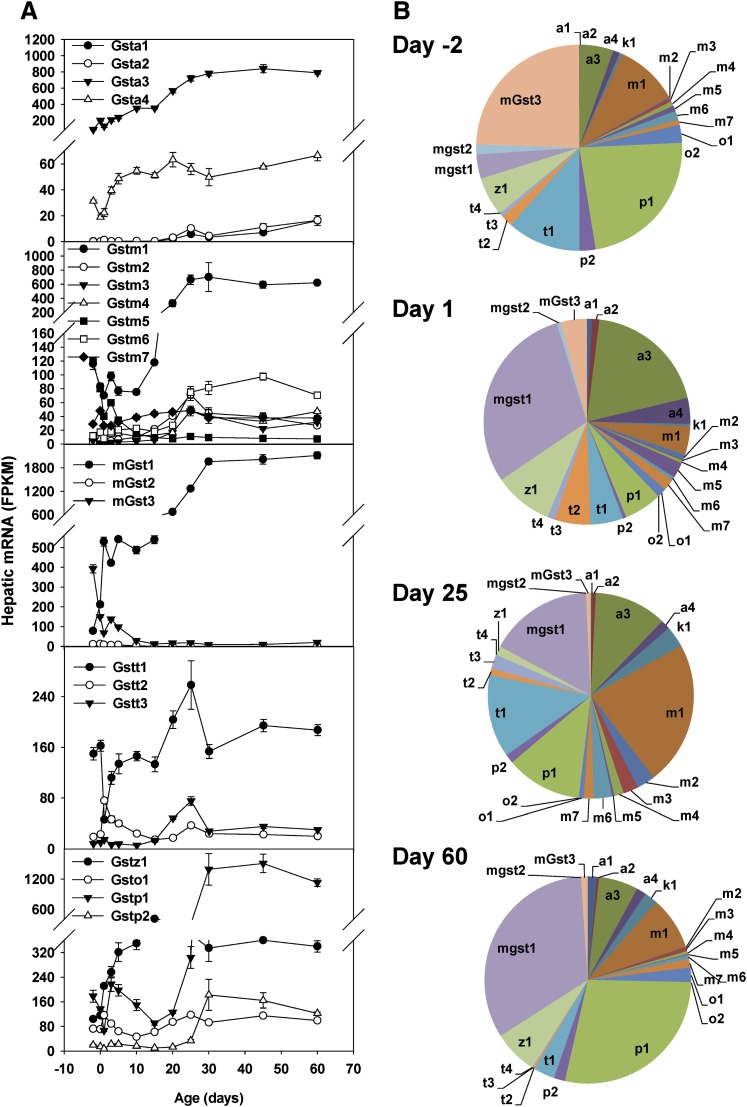

Various Gst subfamily members had distinct ontogenic expression patterns during liver development (Fig. 5). Members of the Gsta subfamily all had adult-predominant expression patterns, with Gsta3 being the predominant Gsta subfamily member, followed by Gsta4 (Fig. 5A). Gsta3 is essential for the protection of mice against DNA damage and hepatotoxicity induced by aflatoxin B1 (Ilic et al., 2010). Among the Gstm subfamily, Gstm1 was the predominant isoform throughout liver development (Fig. 5A). Gstm1 is essential for the protection of mice against methemoglobinemia induced by 1,2-dichloro-4-nitrobenzene through GSH conjugation (Arakawa et al., 2010). Gstm1, -m4, and -m6 had adult-predominant, Gstm2 and -m3 had adolescent-predominant, and Gstm5 had fetal-predominant expression patterns, whereas Gstm7 had no significant ontogenic changes (Fig. 5A). Among the microsomal Gst (mGst) subfamily, there was an ontogenic switch during liver development: mGst3 was the predominant mGst in fetal liver, whereas mGst1 was the predominant mGst in adult liver, due to marked postnatal downregulation of mGst3 but an increase of mGst1 (Fig. 5A). Similar to mGst3, hepatic mGst2 transcripts were markedly decreased during postnatal liver development. The most abundant Gstt subfamily was Gstt1, an enzyme essential for GSH conjugation of 1,2-epoxy-3-(p-nitrophenoxy)propane, dichloromethane, and the alkylating drug 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (Fujimoto et al., 2007). Gstt1 and Gstt3 had the adolescent-predominant expression pattern, whereas Gstt2 mRNA expression surged 1 day after birth and then decreased to prenatal levels in adulthood (Fig. 5A). Gstz1 is required for the metabolism of maleylacetoacetate (the penultimate step in the catabolism of phenylalanine and tyrosine) and α-halo acids, a carcinogenic contaminant of chlorinated water (Lim et al., 2004). Gstp1/p2 play important and complicated roles in the metabolism of xenobiotics (Henderson and Wolf, 2011). Gstz1, Gstp1, and Gstp2 had adult-predominant expression patterns, whereas mRNA expression of Gsto1 fluctuated during postnatal liver development (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Hepatic ontogeny of Gst mRNAs in male C57BL/6J mice. Livers from C57BL/6J mice of ages −2 to 60 days were used for RNA-seq quantification. (A) The y-axis represents mRNAs expressed as FPKM. n = 3, mean ± S.E. (B) Pie charts representing relative mRNA expression of each Gst isoform as the percentage of total Gst transcripts.

Before birth (day −2), mGst3 was the most abundant Gst in liver, followed by Gstp1, -t1, and -m1 (Fig. 5B). On day 1, mGst1 replaced mGst3 as the most abundant Gst isoform, followed by Gsta3, -z1, and -p1. On day 25, Gstm1 was the most abundant, followed by mGst1, Gstt1, and Gsta3. On day 60, Gstp1 and mGst1 were the two most abundant Gst isoforms, followed by Gstm1 and Gsta3 (Fig. 5B).

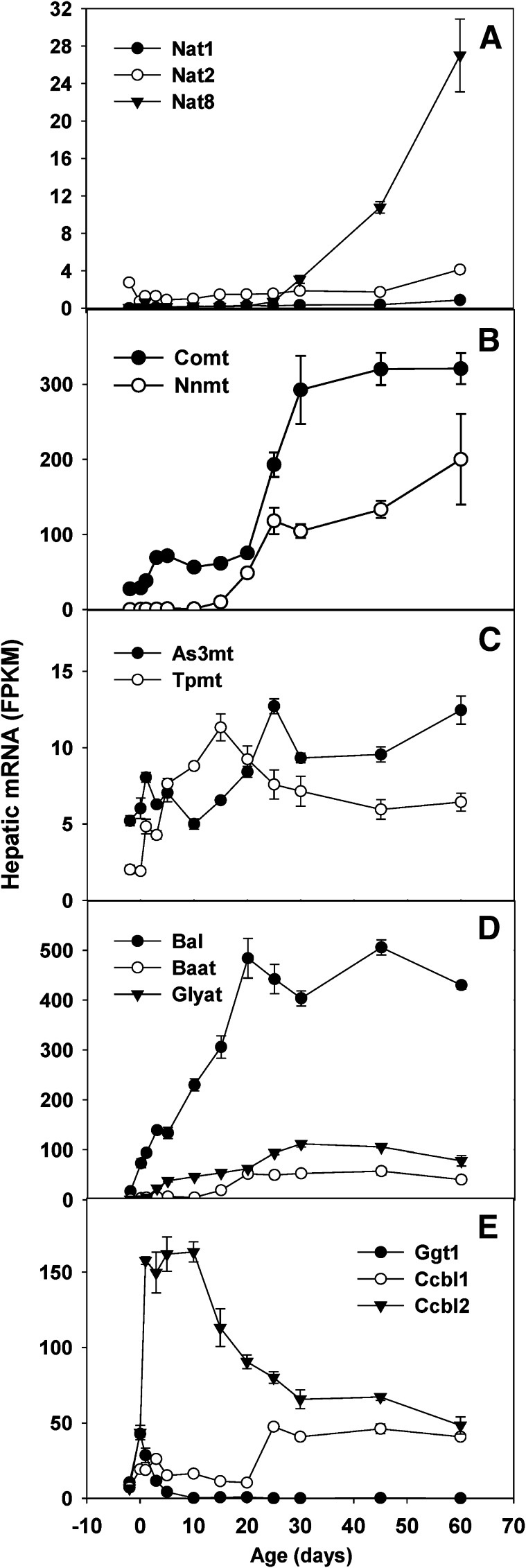

Hepatic Ontogeny of Nat, Methyltransferase, and AA-Conjugating Enzymes in Male C57BL/6J Mice.

Acetylation catalyzed by the arylamine N-acetyltransferases Nat1, Nat2, and Nat3 is a major biotransformation pathway for arylamine and hydrazine drugs, as well as many carcinogens (Sim et al., 2008). Nat1 and Nat2 mRNAs were expressed at low levels before birth, increased gradually during postnatal liver development, and reached the highest levels at day 60 (Fig. 6A). Nat3 mRNAs were undetectable in mouse liver (unpublished data). Nat8 is a newly identified enzyme for mercapturic acid synthesis via acetylation of the cysteine S-conjugates (Veiga-da-Cunha et al., 2010). Hepatic mRNA expression of Nat8 changed remarkably during development: Nat8 mRNA was barely detectable through day 25 and increased rapidly starting from day 30, reaching the highest expression on day 60.

Fig. 6.

(A-E) Hepatic ontogeny of transcripts of Nat, methyltransferase, and AA-conjugating enzymes in male C57BL/6J mice. Livers from C57BL/6J mice of ages −2 to 60 days were used for RNA-seq quantification. The y-axis represents mRNAs expressed as FPKM. n = 3, mean ± S.E.

Catechol O-methyltransferase (Comt) catalyzes the methylation of large amounts of phenolic compounds. Hepatic Comt mRNA was moderately expressed at day −2 before birth and surged during two stages of postnatal development: perinatal stage (from day 1 to day 3) and postweaning stage (from day 20 to day 25) (Fig. 6B). Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (Nnmt) is a cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the N-methylation of nicotinamide, pyridines, and other structural analogs (Aksoy et al., 1994). The most dramatic ontogenic change in methyltransferases was observed for Nnmt; hepatic Nnmt mRNA was very low until day 10; thereafter it increased rapidly and reached a high level on day 60 (Fig. 6B). Arsenic (+3 oxidation state) methyltransferase (As3mt) is the arsenic methyltransferase that protects against arsenic toxicity by converting inorganic arsenic to the methylated metabolite (Sumi and Himeno, 2012). Hepatic As3mt mRNAs were moderately altered during development; As3mt mRNA was at twice the amount in adult than in fetal stage. Thiopurine S-methyltransferase (Tpmt) plays an important role in the metabolism and detoxification of some thiopurine drugs used in pediatric leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease (Mladosievicova et al., 2011). After birth, hepatic Tpmt mRNA gradually increased to the highest level on day 15 and then slightly decreased to 3-fold the fetal level on day 60 (Fig. 6C).

Bile acid-CoA ligase (Bal/Slc27a5) and bile acid-CoA:AA N-acyltransferase (Baat) are two key enzymes for conjugation of bile acids with glycine and taurine (Clayton, 2011). Glycine-N-acyltransferase (Glyat) catalyzes glycine conjugation, a Phase II detoxification process for endogenous chemicals and xenobiotics, such as salicylic acid, benzoic acid, and methylbenzoic acid (Badenhorst et al., 2012). Before birth, Bal was already expressed moderately, and its expression was markedly increased during postnatal development, reaching the highest levels on day 20, and fluctuated thereafter (Fig. 6D). Before birth, hepatic mRNA expression of Baat and Glyat was very low (Fig. 6E). After birth, these 2 AA conjugation enzymes were increased at different developmental stages: Glyat mRNA surged from day 0 to day 3 and increased to adult levels on day 25. In contrast, hepatic Baat mRNA remained low until day 10, after which it surged from day 10 to day 20 and maintained at high levels thereafter.

γ-Glutamyltransferase 1 (Ggt1) plays a key role in the γ-glutamyl cycle, a pathway for the synthesis and degradation of GSH as well as drug and xenobiotic detoxification. Ggt1 catalyzes the formation of cysteine conjugates of xenobiotics. Cysteine conjugate-β-lyase 1 (Ccbl1) and Ccbl2 catalyze the metabolism of cysteine conjugates of certain halogenated alkenes and alkanes, which often results in the formation of reactive metabolites leading to nephrotoxicity (Cooper and Pinto, 2006). Hepatic mRNA expression of Ccbl1 fluctuated during the first 20 days of postnatal development, surged 4-fold from day 20 to day 25 (after weaning), and stayed constant thereafter (Fig. 6E). In contrast, hepatic Ccbl2 mRNA increased 23-fold from 2 days before birth (day −2) to 1 day after birth (day 1) and decreased markedly starting from day 10, reaching day 0 level at adulthood (Fig. 6E).

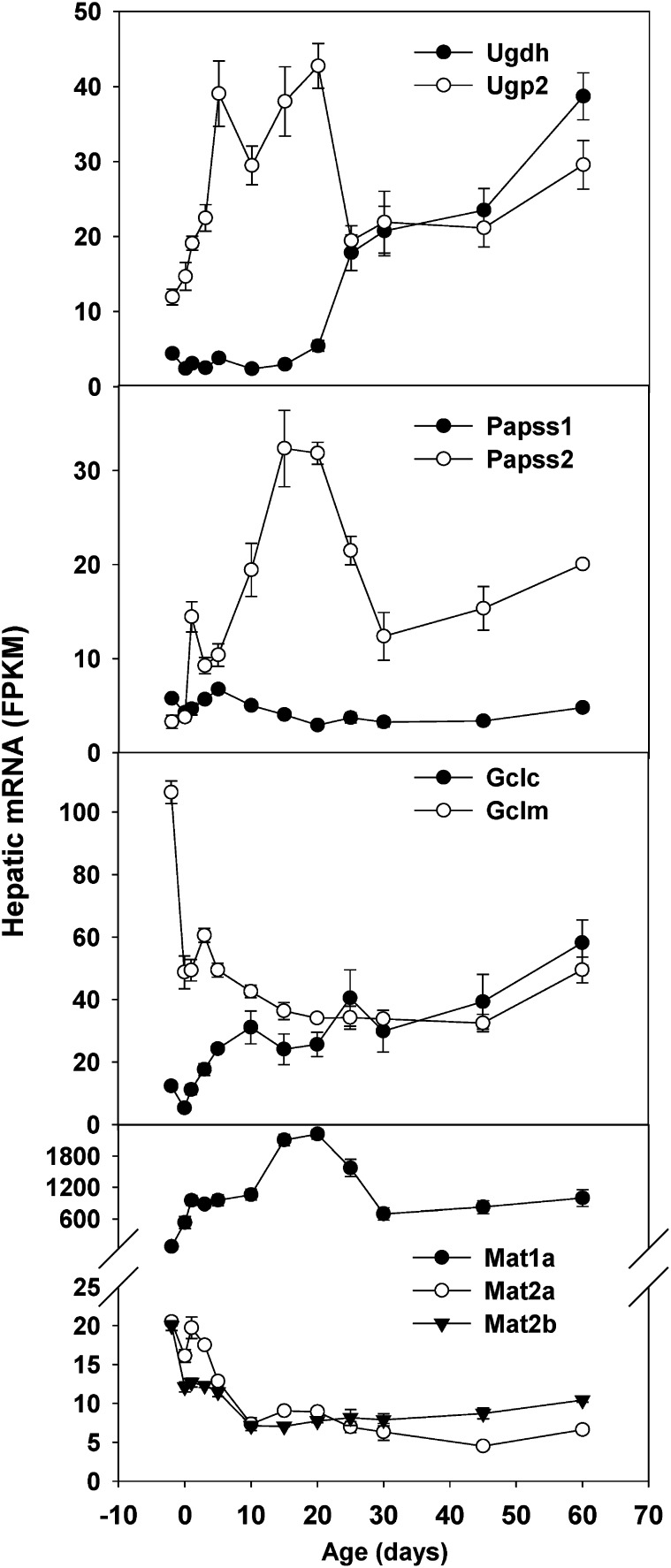

Hepatic Ontogeny of mRNAs Encoding Enzymes Responsible for Synthesis of Cosubstrates for Phase II Conjugation Reactions in Male C57BL/6J Mice.

UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 2 (Ugp2) catalyzes the synthesis of UDP-glucose, whereas UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase (Ugdh) converts UDP-glucose to UDP-glucuronate, the cosubstrate for UDP-glucuronidation. Hepatic Ugp2 mRNA increased 4-fold from day −2 to day 5 and slightly decreased after weaning (day 25). In contrast, hepatic Ugdh mRNA expression did not increase until after weaning and reached the highest level at adulthood (day 60) (Fig. 7). 3′-Phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthase 1 (Papss1) and Papss2 catalyze the synthesis of PAPS, the sulfate donor cosubstrate for all sulfotransferases. Hepatic Papss1 mRNA remained constantly low throughout development. In contrast, there was a day 1 surge in hepatic Papss2 mRNA, which peaked on day 15 and decreased slightly thereafter. Glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic (Gclc) and modifier (Gclm) subunit are enzymes for the synthesis of GSH, the cosubstrate for all Gst enzymes. Interestingly, hepatic Gclc mRNA increased but Gclm mRNA decreased during liver maturation (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Hepatic ontogeny of mRNAs of genes encoding enzymes for the synthesis of cosubstrates for Phase II conjugation in male C57BL/6J mice. Livers from C57BL/6J mice of ages −2 to 60 days were used for RNA-seq quantification. The y-axis represents mRNAs expressed as FPKM. n = 3, mean ± S.E.

There was a marked ontogenic switch in hepatic expression of enzymes for the synthesis of the common methyl donor S-adenosylmethionine. Methionine adenosyltransferase 1a (Mat1a) expression increased markedly, whereas Mat2a and Mat2b mRNAs decreased moderately (48–68%) during postnatal development (Fig. 7).

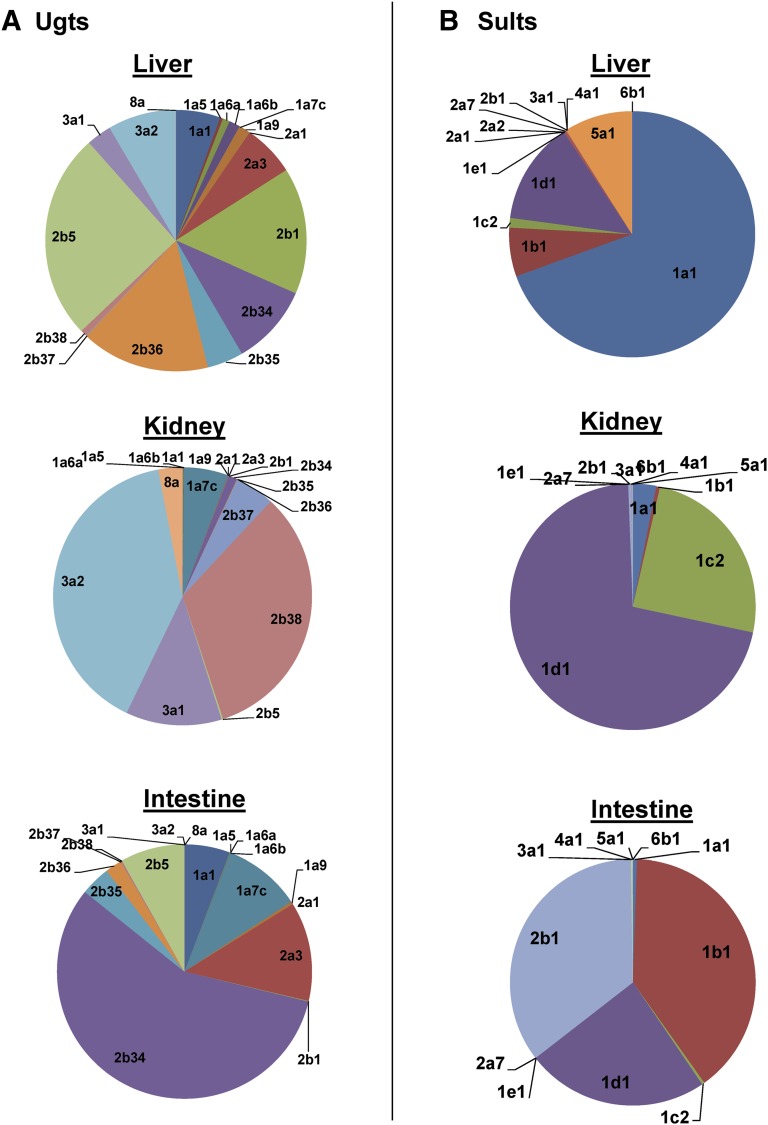

Tissue Distribution of Phase II Enzymes in Adult Liver, Kidney, and Small Intestine in Male C57BL/6J Mice.

The three major tissues of drug processing, namely liver, kidney, and small intestine, differed sharply in the expression of various Phase II enzymes. In liver, Ugt2b5, -2b36, and -2b1 were the most abundant Ugt enzymes. In kidney, Ugt3a2, -2b38, and -3a1 accounted for >75% of total Ugt transcripts. In contrast, in small intestine, Ugt2b34 accounted for >50% of total Ugt transcripts, followed by Ugt2a3 and -1a7c (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 8.

Tissue distribution of mRNAs of genes encoding Ugt and Sult enzymes in adult male C57BL/6J mice. (A) Pie charts representing relative mRNA expression of each Ugt isoform as the percentage of total Ugt transcripts in liver, kidney, and small intestine, respectively, from C57BL/6J mice 60 days old. n = 2, mean. (B) Pie charts representing relative mRNA expression of each Sult isoform as the percentage of total Sult transcripts in liver, kidney, and small intestine, respectively, from C57BL/6J mice 60 days old. n = 2, mean.

In liver, Sult1a1 accounted for >65% of total Sult transcripts, followed by Sult1d1 and Sult5a1. In kidney, Sult1d1 accounted for >65% of total Sult transcripts, followed by Sult1c2 and Sult1a1, with other Sult transcripts expressed at low levels. In small intestine, three Sult members, namely Sult1b1, -2b1, and -1d1, accounted for almost all Sult transcripts (Fig. 8B).

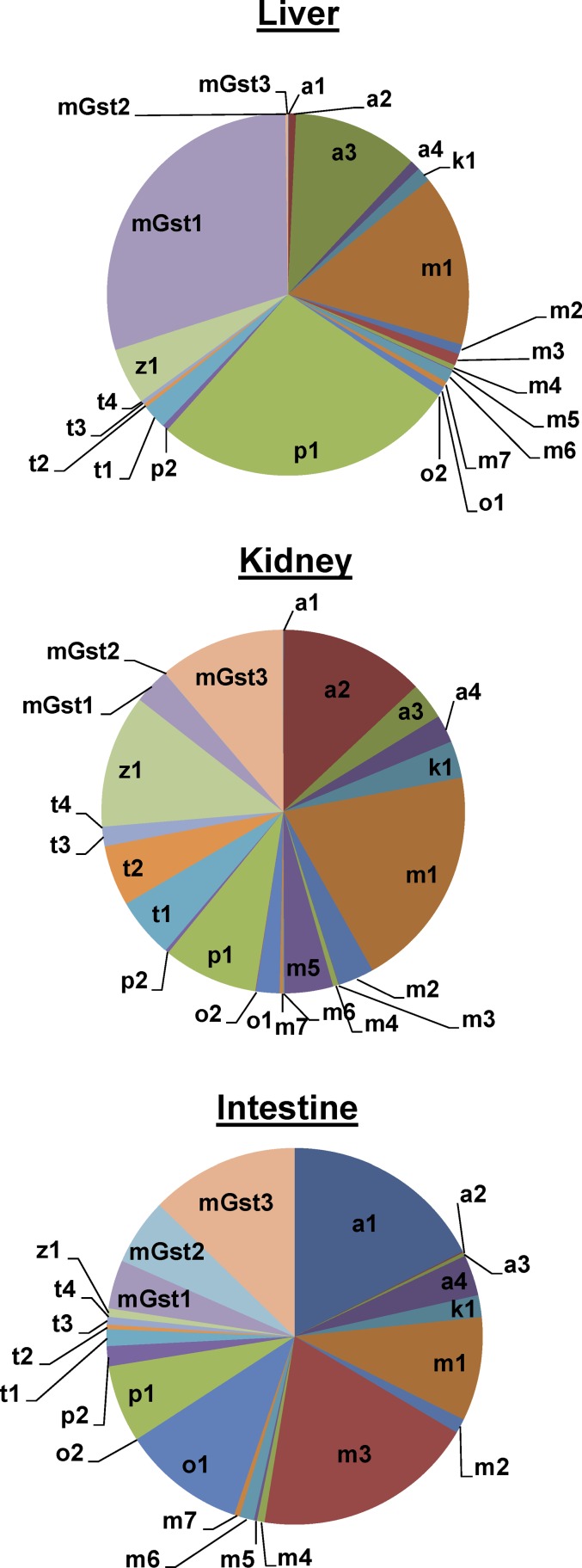

Compared with Ugt and Sult enzymes, the expression of Gst family members was more diversified among the three tissues (Fig. 9). In liver, mGst1, Gstp1, Gstm1, and Gsta3 were the most abundant Gst transcripts. In kidney, Gstm1, Gsta2, mGst3, and Gstz1 were the most abundant Gst transcripts. In contrast, in small intestine, Gsta1, Gstm3, mGst3, and Gsto1 were the most highly expressed Gst transcripts.

Fig. 9.

Tissue distribution of mRNAs of genes encoding Gst enzymes in adult male C57BL/6J mice. Pie charts representing relative mRNA expression of each Gst isoform as the percentage of total Gst transcripts in liver, kidney, and small intestine, respectively, from C57BL/6J mice 60 days old. n = 2, mean.

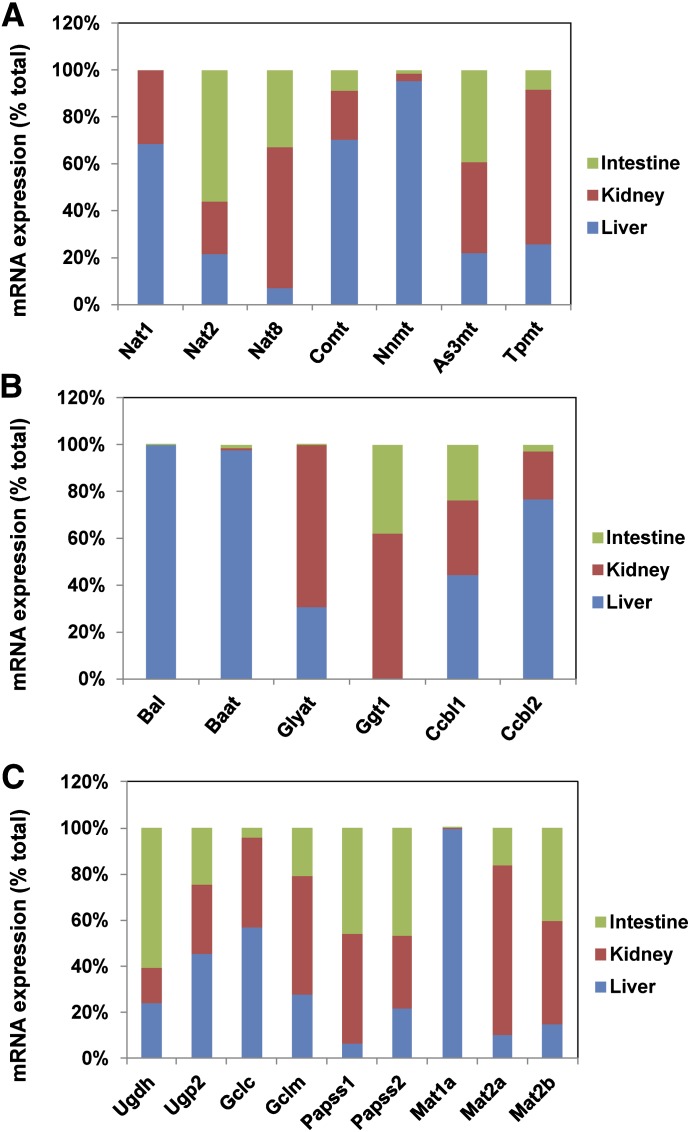

The distribution of Nat mRNAs was less tissue-specific compared with other Phase II enzymes. In all three tissues of liver, kidney, and small intestine, Nat8 was the most abundant, followed by Nat2 and Nat1 (unpublished data). Nat1 was only expressed in liver and kidney, Nat2 was highest in small intestine, whereas Nat8 was predominant in kidney (Fig. 10A). Regarding methyltransferases, Comt and Nnmt were liver-predominant, Tpmt was kidney-predominant, whereas As3mt expression was less variable among the three tissues (Fig. 10A).

Fig. 10.

Tissue distribution of mRNAs of genes encoding other Phase II enzymes and enzymes responsible for the synthesis of cosubstrates for Phase II conjugation reactions in adult male C57BL/6J mice. (A and B) Stacked column charts representing relative mRNA expression of each Phase II enzyme as the percentage of total transcripts of this enzyme in liver, kidney, and small intestine from C57BL/6J mice 60 days old. n = 2, mean. (C) Stacked column chart representing relative mRNA expression of each cosubstrate-synthesizing enzyme as the percentage of total transcripts of this enzyme in liver, kidney, and small intestine from C57BL/6J mice 60 days old. n = 2, mean.

Among the AA conjugation enzymes, Bal and Baat were highly liver-specific, whereas Glyat was only expressed in liver and kidney (Fig. 10B). Ggt1 was only expressed in kidney and intestine, Ccbl2 was liver-predominant, whereas Ccbl1 was less variable among the three tissues (Fig. 10B).

The tissue distribution of enzymes for the synthesis of cosubstrates was generally less variable compared with Phase II enzymes (Fig. 10C). Tissues with the highest expression were liver for Ugp2, Gclc, and Mat1a; kidney for Gclm, Papss1, Mat2a, and Mat2b; and small intestine for Ugdh and Papss2 (Fig. 10C).

Real-Time PCR Validation of RNA-Seq Data.

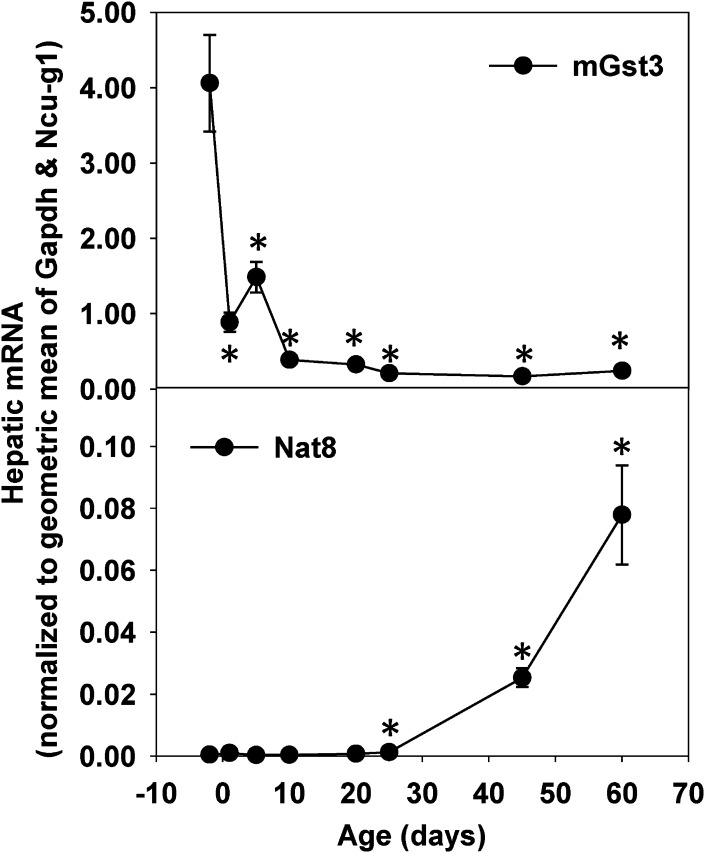

Consistent with RNA-seq data (Figs. 5A and 6), real-time PCR data showed that hepatic mRNA expression of mGst3 was substantially downregulated during postnatal development, whereas Nat8 mRNA was barely detectable until day 25, but surged from day 25 to day 60 (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Real-time PCR validation of RNA-seq data on ontogenic mRNA expression of mGst3 and Nat8 in livers of male C57BL/6J mice. Total RNAs from livers of male C57BL/6J mice of ages −2, 1, 5, 10, 20, 25, 45, and 60 days were used for real-time PCR validation. n = 3, mean ± S.E. The y-axis represents mRNAs calculated by the comparative computed tomography method, which determines the amount of target normalized to the geometric mean of Gapdh and Ncu-g1. *P < 0.05 vs. day −2.

Discussion

The present study, for the first time, provides comprehensive quantitative analysis of developmental regulation of mRNA expression of all major Phase II enzymes, including enzymes involved in glucuronidation, sulfation, GSH conjugation, acetylation, methylation, and AA conjugation in mouse liver. Many of these Phase II enzymes display marked ontogenic changes in mRNA expression in liver, with a majority of them induced during postnatal liver development. In adulthood, these Phase II enzymes have distinct expression levels in the three major tissues of drug processing, namely liver, kidney, and small intestine.

The present data on hepatic ontogeny and tissue distribution of Sult enzymes are consistent with a previous report (Alnouti and Klaassen, 2006). Nevertheless, RNA-seq data illustrate the relative abundance of various Sult family members during liver development and among adult tissues, which were not known previously. It is noteworthy that although Sult2a isoforms are largely silenced in adult male mouse livers, they remain actively transcribed in adult female mouse livers (Alnouti and Klaassen, 2006). Additionally, although Sult3a1 is not expressed in adult male mouse livers, it is expressed appreciably in livers of adult female mice (Alnouti and Klaassen, 2006).

The present data on hepatic ontogeny and tissue distribution of Gst enzymes are largely consistent with previous reports (Knight et al., 2007; Cui et al., 2010), with the exception of mGst3. In the present study, results from both RNA-seq and real-time PCR showed that mGst3 was the most abundant Gst in mouse liver before birth, and mGst3 was substantially downregulated during postnatal liver development (Figs. 5A and 11). In contrast, a previous study showed that hepatic mGst3 mRNA increased moderately (∼1-fold) from day −2 to day 0 and remained unchanged thereafter (Cui et al., 2010). The reason for such apparent difference in hepatic ontogeny of mGst3 in mice remains unclear, but appears unlikely due to strain difference, because C57BL/6 mice were used in these two studies. In humans, mGST3 mRNA expression is low in adult liver, but appears to be high in fetal liver (Jakobsson et al., 1997). Thus, apparently, both humans and mice have ontogenic downregulation of mGST3 during postnatal liver development. mGst3 has been implicated in the synthesis of leukotriene C4 and possesses GSH-dependent peroxidase activity (Jakobsson et al., 1997).

The present study illustrates the first ontogenic patterns of mRNA expression of Ugt enzymes in mouse liver. Physiologic functions change dramatically from fetal liver to adult liver. Adult liver is the major organ to metabolize AAs and lipids, to maintain gluconeogenesis, to synthesize serum proteins, and to detoxify metabolic wastes and xenobiotics. In contrast, fetal liver has fewer metabolic functions and is a major organ for hematopoiesis. The perinatal surge of Ugt1a1 is consistent with the key role of Ugt1a1 in glucuronidation of bilirubin and prevention of hyperbilirubinemia (Kadakol et al., 2000). In contrast, the rapid increase in hepatic mRNA expression of many Ugt2b family members during weaning (day 20 to day 30) (Fig. 3) is consistent with their important role in the glucuronidation of steroid hormones and xenobiotics (Bock, 2010). Ugp2 catalyzes the synthesis of UDP-glucose, whereas Ugdh converts UDP-glucose to UDP-glucuronate, the cosubstrate for UDP-glucuronidation. UDP-glucose also serves as the precursor for glycogen synthesis. The increased need for glucuronidation of endogenous chemicals and the postnatal depletion of hepatic glycogen might be the driving force of the adolescent-predominant expression pattern of Ugp2 (Fig. 7), whose expression decreases moderately after the replenishment of glycogen storage in adolescent liver (Lopez et al., 1999). In contrast, the delayed surge in hepatic expression of Ugdh right after weaning (Fig. 7) coincides with marked increases in ingestion of xenobiotics and glucuronidation of these xenobiotics after weaning.

The present study, for the first time, illustrates ontogenic patterns of mRNA expression of Phase II enzymes for acetylation and methylation in mouse liver. Hepatic mRNA expression of Nat enzymes involved in xenobiotic metabolism, such as Nat1, Nat2, and Nat8, is increased with liver maturation (Fig. 6). Comt is important in the metabolism of hormones (e.g., catecholamines and estrogens) and a large number of dietary phenolic compounds (Zhu, 2002). The two surges in Comt expression during perinatal (day 1 to day 3) and postweaning (day 20 to day 25) might correspond to the markedly increased need for the metabolism of hormones and dietary phenolic compounds, respectively, during postnatal development. Nnmt catalyzes the N-methylation of nicotinamide, pyridines, and other structural analogs; its expression increases substantially with liver maturation. Interestingly, hepatic NNMT is markedly downregulated in liver cancer patients (Kim et al., 2009). The regulatory mechanism of Nnmt expression during liver development and carcinogenesis warrants further investigation.

The present data suggest that neonatal mouse livers might differ considerably from adult livers regarding the metabolism of GSH conjugates. GSH conjugation is initiated by transfer of GSH onto an electrophilic acceptor (such as the anticancer drug cisplatin and toxicants ethylene dibromide and acrylamide), followed either by direct excretion of the GSH conjugates from the hepatocytes into bile, or by the hydrolysis of glutamate by Ggt to form cysteinyl-glycine-S-conjugates. Certain dipeptidases present in kidney and liver can hydrolyze the cysteinyl-glycine-S-conjugates to cysteine S-conjugates. Nat8 catalyzes the acetylation of the cysteine S-conjugates in liver or kidney, leading to the formation of mercapturic acids, which are more polar and water-soluble than the original electrophiles and are readily excreted in urine or bile by multidrug resistance proteins. In the absence of acetylation, cysteinyl conjugates are unstable, undergoing β-elimination catalyzed by Ccbl, with formation of toxic sulfur derivatives (Monks et al., 1990). Compared with adult mouse livers, the newborn mouse livers have much higher expression of Ggt1 and Ccbl2 (Fig. 7) but very low expression of Nat8 (Fig. 6), which might result in a higher formation of toxic metabolites of certain GSH conjugates in newborns via the Ggt-Ccbl2 β-elimination pathway.

RNA-seq provides the first genome-wide approach of true quantification of transcripts, which allows quantitative comparison of the abundance of various members within each gene family in various tissues. Such knowledge may be particularly useful for the study of the physiologic function of a given Phase II enzyme when using mice with targeted deletion of this gene. For example, Sult1a1, a major Sult with broad substrate specificity (Hempel et al., 2007), accounts for >60% of the total Sult transcripts in mouse liver, but only accounts for a very small percentage of total Sult transcripts in kidney and small intestine. Therefore, loss of Sult1a1 is expected to markedly affect the sulfation of certain chemicals in liver, but may have minimal effect on the sulfation of these chemicals in kidney and small intestine. In contrast, loss of Sult1d1 (a key enzyme for catecholamine sulfation) (Shimada et al., 2004) and Ugt2b34 may markedly affect the sulfation and glucuronidation of chemicals in kidney and small intestine, respectively, because Sult1d1 accounts for >70% of total Sult transcripts in kidney, whereas Ugt2b34 accounts for >50% of total Ugt transcripts in small intestine.

It is noteworthy that only the mRNA levels of these Phase II enzymes were investigated in this study. More studies are needed to determine whether the marked differences in mRNA expression of these Phase II enzymes during different stages of liver development and among the three adult tissues of liver, kidney, and small intestine translate into differences in their protein expression and enzymatic function. Two recent genome-scale studies indicate that in mammalian cells, mRNA levels explain ∼40% of the variation in protein levels (Schwanhausser et al., 2011); however, transcript levels correlate more strongly with clinical traits than protein levels (Ghazalpour et al., 2011). It is noteworthy that the ADME of xenobiotics depends on the cellular milieu composed of various transporters and metabolic enzymes coordinately regulated by a group of transcription factors (Klaassen and Slitt, 2005). Transcript levels of ADME genes might better reflect the cellular milieu for the ADME of xenobiotics under certain pathophysiological conditions. Bisphenol A (BPA) is an important industrial and environmental chemical. Phase II conjugation reaction plays the key role in limiting the body's exposure to the parent unconjugated BPA, which is a well characterized endocrine disruptor (Taylor et al., 2011). Results from a comparative study on pharmacokinetics of BPA in neonatal and adult CD-1 mice demonstrate that neonatal mice (on day 3 and day 10) have much higher blood levels of unconjugated BPA than adult mice after oral ingestion. In contrast, postweaning (day 21) mice have blood levels of unconjugated BPA comparable to those in adult mice (Doerge et al., 2011). Glucuronidation is the major metabolic pathway for BPA in mice (Zalko et al., 2003). In parallel, the present data demonstrate that most Ugt enzymes are expressed at low levels in neonatal mice (day 3 and day 10) but at high, adult-comparable levels in postweaning mice (day 25). Thus, it appears that the marked differences in mRNA expression of these Ugt enzymes during different stages of liver development translate into differences in their protein expression and enzymatic function. Technological breakthroughs in proteomics and metabolomics are essential to conduct genome-scale comparative study to identify the sets of genes whose ontogenic expression are mainly regulated at transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels, respectively.

Although the mechanism of the ontogenic changes in hepatic expression of Phase II enzymes is still unknown, literature suggests that growth hormone (GH) and androgens play key roles in the regulation of gender- and age-specific gene expression (Waxman and Holloway, 2009; Baik et al., 2011). The female- and male-predominant expression of Ugt1a1 and Ugt2b1, respectively, in mouse liver is due to suppression of Ugt1a1 mRNA but induction of Ugt2b1 mRNA by male-pattern GH secretion (Buckley and Klaassen, 2009). Thus, the decrease in hepatic expression of Ugt1a1 but induction of Ugt2b1 in male mice upon puberty (after day 25) (Fig. 3A) is likely due to the establishment of male-pattern GH secretion upon puberty. Sult2a1/a2 has a markedly female-predominant expression in adult mouse liver due to suppressive effects of androgens and male-pattern GH secretion, as well as stimulatory effects by estrogens and female-pattern GH secretion (Alnouti and Klaassen, 2011). Thus, the marked hepatic downregulation of Sult2a1/2 and other Sult2a enzymes in male mice upon puberty (after day 25) (Fig. 4A) may be due to the increase of androgens and establishment of male-pattern GH secretion upon puberty. Similarly, Sult1a1 and Sult1d1 have moderately female-predominant expression in adult mouse liver (Alnouti and Klaassen, 2006) due to suppressive effects of androgens and male-pattern GH secretion (Alnouti and Klaassen, 2011). Therefore, the moderate hepatic downregulation of Sult1a1 and Sult1d1 in male mice upon puberty (after day 25) (Fig. 4A) may be due to the increase of androgens and establishment of male-pattern GH secretion upon puberty.

In summary, the present study provides the first knowledge about the true quantification of ontogenic patterns of mRNA expression of all major known Phase II enzymes during mouse liver development and the distribution of these mRNAs among the three key tissues of ADME, namely liver, kidney, and small intestine, in adulthood. Such knowledge will serve as the foundation for further study on the regulation of gene expression and physiologic function of these Phase II enzymes during liver development, as well as the mechanism of tissue-specific gene expression and the physiologic importance of these Phase II enzymes in these three key tissues of ADME.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Xiaohong Lei, Lai Peng, and Helen Renaud for technical assistance in animal experiments, as well as Clark Bloomer from the University of Kansas Medical Center Sequencing Core Facilities for his technical assistance in mRNA-seq.

Abbreviations

- AA

amino acid

- ADME

absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion

- As3mt

arsenic (+3 oxidation state) methyltransferase

- Baat

bile acid-CoA:amino acid N-acyltransferase

- Bal

bile acid-CoA ligase

- bp

basepair

- BPA

bisphenol A

- Ccbl1

cysteine conjugate-β-lyase 1

- Comt

catechol O-methyltransferase

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped

- Gclc

glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit

- Gclm

glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit

- Ggt1

γ-glutamyltransferase 1

- GH

growth hormone

- Glyat

glycine-N-acyltransferase

- GSH

glutathione

- Gst

glutathione S-transferase

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathways Analysis

- IPKB

Ingenuity Pathway Knowledge Base

- Mat1a

methionine adenosyltransferase 1a

- Nat

N-acetyltransferase

- Nnmt

nicotinamide N-methyltransferase

- Papss1

3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthase 1

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- Sult

sulfotransferase

- Tpmt

thiopurine S-methyltransferase

- Ugdh

UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase

- Ugp2

UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 2

- Ugt

uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Lu, Gunewardena, Yoo, Zhong, Klaassen.

Conducted experiments: Lu, Cui.

Performed data analysis: Lu, Gunewardena, Cui, Yoo.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Lu, Gunewardena, Cui, Yoo, Zhong, Klaassen.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Grant ES-019487]; and the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources [Grant RR-021940].

This article has supplemental material available at dmd.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at dmd.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Aksoy S, Szumlanski CL, Weinshilboum RM. (1994) Human liver nicotinamide N-methyltransferase. cDNA cloning, expression, and biochemical characterization. J Biol Chem 269:14835–14840 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alnouti Y, Klaassen CD. (2006) Tissue distribution and ontogeny of sulfotransferase enzymes in mice. Toxicol Sci 93:242–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alnouti Y, Klaassen CD. (2011) Mechanisms of gender-specific regulation of mouse sulfotransferases (Sults). Xenobiotica 41:187–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa S, Maejima T, Kiyosawa N, Yamaguchi T, Shibaya Y, Aida Y, Kawai R, Fujimoto K, Manabe S, Takasaki W. (2010) Methemoglobinemia induced by 1,2-dichloro-4-nitrobenzene in mice with a disrupted glutathione S-transferase Mu 1 gene. Drug Metab Dispos 38:1545–1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badenhorst CP, Jooste M, van Dijk AA. (2012) Enzymatic characterization and elucidation of the catalytic mechanism of a recombinant bovine glycine N-acyltransferase. Drug Metab Dispos 40:346–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baik M, Yu JH, Hennighausen L. (2011) Growth hormone-STAT5 regulation of growth, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver metabolism. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1229:29–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake MJ, Castro L, Leeder JS, Kearns GL. (2005) Ontogeny of drug metabolizing enzymes in the neonate. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 10:123–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock KW. (2010) Functions and transcriptional regulation of adult human hepatic UDP-glucuronosyl-transferases (UGTs): mechanisms responsible for interindividual variation of UGT levels. Biochem Pharmacol 80:771–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley DB, Klaassen CD. (2009) Mechanism of gender-divergent UDP-glucuronosyltransferase mRNA expression in mouse liver and kidney. Drug Metab Dispos 37:834–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushey RT, Dluzen DF, Lazarus P. (2013) Importance of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases 2A2 and 2A3 in tobacco carcinogen metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos 41:170–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton PT. (2011) Disorders of bile acid synthesis. J Inherit Metab Dis 34:593–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AJ, Pinto JT. (2006) Cysteine S-conjugate beta-lyases. Amino Acids 30:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui JY, Choudhuri S, Knight TR, Klaassen CD. (2010) Genetic and epigenetic regulation and expression signatures of glutathione S-transferases in developing mouse liver. Toxicol Sci 116:32–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui JY, Gunewardena SS, Yoo B, Liu J, Renaud HJ, Lu H, Zhong XB, Klaassen CD. (2012) RNA-Seq reveals different mRNA abundance of transporters and their alternative transcript isoforms during liver development. Toxicol Sci 127:592–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerge DR, Twaddle NC, Vanlandingham M, Fisher JW. (2011) Pharmacokinetics of bisphenol A in neonatal and adult CD-1 mice: inter-species comparisons with Sprague-Dawley rats and rhesus monkeys. Toxicol Lett 207:298–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K, Arakawa S, Watanabe T, Yasumo H, Ando Y, Takasaki W, Manabe S, Yamoto T, Oda S. (2007) Generation and functional characterization of mice with a disrupted glutathione S-transferase, theta 1 gene. Drug Metab Dispos 35:2196–2202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk RS, Brown JT, Abdel-Rahman SM. (2012) Pediatric pharmacokinetics: human development and drug disposition. Pediatr Clin North Am 59:1001–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazalpour A, Bennett B, Petyuk VA, Orozco L, Hagopian R, Mungrue IN, Farber CR, Sinsheimer J, Kang HM, Furlotte N, et al. (2011) Comparative analysis of proteome and transcriptome variation in mouse. PLoS Genet 7:e1001393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatt H. (2000) Sulfotransferases in the bioactivation of xenobiotics. Chem Biol Interact 129:141–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempel N, Gamage N, Martin JL, McManus ME. (2007) Human cytosolic sulfotransferase SULT1A1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 39:685–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson CJ, Wolf CR. (2011) Knockout and transgenic mice in glutathione transferase research. Drug Metab Rev 43:152–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines RN. (2008) The ontogeny of drug metabolism enzymes and implications for adverse drug events. Pharmacol Ther 118:250–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Bathena SP, Tong J, Roth M, Hagenbuch B, Alnouti Y. (2010) Kinetic analysis of bile acid sulfation by stably expressed human sulfotransferase 2A1 (SULT2A1). Xenobiotica 40:184–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic Z, Crawford D, Vakharia D, Egner PA, Sell S. (2010) Glutathione-S-transferase A3 knockout mice are sensitive to acute cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of aflatoxin B1. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 242:241–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson PJ, Mancini JA, Riendeau D, Ford-Hutchinson AW. (1997) Identification and characterization of a novel microsomal enzyme with glutathione-dependent transferase and peroxidase activities. J Biol Chem 272:22934–22939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jancova P, Anzenbacher P, Anzenbacherova E. (2010) Phase II drug metabolizing enzymes. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 154:103–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadakol A, Ghosh SS, Sappal BS, Sharma G, Chowdhury JR, Chowdhury NR. (2000) Genetic lesions of bilirubin uridine-diphosphoglucuronate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT1A1) causing Crigler-Najjar and Gilbert syndromes: correlation of genotype to phenotype. Hum Mutat 16:297–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Hong SJ, Lim EK, Yu YS, Kim SW, Roh JH, Do IG, Joh JW, Kim DS. (2009) Expression of nicotinamide N-methyltransferase in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with poor prognosis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 28:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen CD, Slitt AL. (2005) Regulation of hepatic transporters by xenobiotic receptors. Curr Drug Metab 6:309–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight TR, Choudhuri S, Klaassen CD. (2007) Constitutive mRNA expression of various glutathione S-transferase isoforms in different tissues of mice. Toxicol Sci 100:513–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna DR, Klotz U. (1994) Extrahepatic metabolism of drugs in humans. Clin Pharmacokinet 26:144–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim CE, Matthaei KI, Blackburn AC, Davis RP, Dahlstrom JE, Koina ME, Anders MW, Board PG. (2004) Mice deficient in glutathione transferase zeta/maleylacetoacetate isomerase exhibit a range of pathological changes and elevated expression of alpha, mu, and pi class glutathione transferases. Am J Pathol 165:679–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MF, Dikkes P, Zurakowski D, Villa-Komaroff L, Majzoub JA. (1999) Regulation of hepatic glycogen in the insulin-like growth factor II-deficient mouse. Endocrinology 140:1442–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Cui JY, Gunewardena S, Yoo B, Zhong XB, Klaassen CD. (2012) Hepatic ontogeny and tissue distribution of mRNAs of epigenetic modifiers in mice using RNA-sequencing. Epigenetics 7:914–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie PI, Rogers A, Elliot DJ, Chau N, Hulin JA, Miners JO, Meech R. (2011) The novel UDP glycosyltransferase 3A2: cloning, catalytic properties, and tissue distribution. Mol Pharmacol 79:472–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie PI, Rogers A, Treloar J, Jorgensen BR, Miners JO, Meech R. (2008) Identification of UDP glycosyltransferase 3A1 as a UDP N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. J Biol Chem 283:36205–36210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone JH, Oliver B. (2011) Microarrays, deep sequencing and the true measure of the transcriptome. BMC Biol 9:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mladosievicova B, Dzurenkova A, Sufliarska S, Carter A. (2011) Clinical relevance of thiopurine S-methyltransferase gene polymorphisms. Neoplasma 58:277–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monks TJ, Anders MW, Dekant W, Stevens JL, Lau SS, van Bladeren PJ. (1990) Glutathione conjugate mediated toxicities. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 106:1–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Yoo B, Gunewardena SS, Lu H, Klaassen CD, Zhong XB. (2012) RNA sequencing reveals dynamic changes of mRNA abundance of cytochromes P450 and their alternative transcripts during mouse liver development. Drug Metab Dispos 40:1198–1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan SL, Maggs JL, Hammond TG, Lambert C, Williams DP, Park BK. (2010) Acyl glucuronides: the good, the bad and the ugly. Biopharm Drug Dispos 31:367–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki Y, Sakakibara Y, Araki Y, Yanagisawa K, Suiko M, Nakajima H, Liu MC. (1998) Molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of a novel mouse liver SULT1B1 sulfotransferase. J Biochem 124:55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanhäusser B, Busse D, Li N, Dittmar G, Schuchhardt J, Wolf J, Chen W, Selbach M. (2011) Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature 473:337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Terazawa R, Kamiyama Y, Honma W, Nagata K, Yamazoe Y. (2004) Unique properties of a renal sulfotransferase, St1d1, in dopamine metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310:808–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim E, Walters K, Boukouvala S. (2008) Arylamine N-acetyltransferases: from structure to function. Drug Metab Rev 40:479–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi D, Himeno S. (2012) Role of arsenic (+3 oxidation state) methyltransferase in arsenic metabolism and toxicity. Biol Pharm Bull 35:1870–1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JA, Vom Saal FS, Welshons WV, Drury B, Rottinghaus G, Hunt PA, Toutain PL, Laffont CM, VandeVoort CA. (2011) Similarity of bisphenol A pharmacokinetics in rhesus monkeys and mice: relevance for human exposure. Environ Health Perspect 119:422–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga-da-Cunha M, Tyteca D, Stroobant V, Courtoy PJ, Opperdoes FR, Van Schaftingen E. (2010) Molecular identification of NAT8 as the enzyme that acetylates cysteine S-conjugates to mercapturic acids. J Biol Chem 285:18888–18898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman DJ, Holloway MG. (2009) Sex differences in the expression of hepatic drug metabolizing enzymes. Mol Pharmacol 76:215–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalko D, Soto AM, Dolo L, Dorio C, Rathahao E, Debrauwer L, Faure R, Cravedi JP. (2003) Biotransformations of bisphenol A in a mammalian model: answers and new questions raised by low-dose metabolic fate studies in pregnant CD1 mice. Environ Health Perspect 111:309–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu BT. (2002) Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)-mediated methylation metabolism of endogenous bioactive catechols and modulation by endobiotics and xenobiotics: importance in pathophysiology and pathogenesis. Curr Drug Metab 3:321–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.