Asp-73, Pro-75, Trp-153, and Trp-160 are essential residues in the PMEL NTR that are required for functional fibril formation. The NTR is necessary in cis to drive the downstream PKD into an amyloid core matrix, which subsequently incorporates and stabilizes the RPT domain–containing, MαC fibril–associated fragment.

Abstract

PMEL (also called Pmel17 or gp100) is a melanocyte/melanoma-specific glycoprotein that plays a critical role in melanosome development by forming a fibrillar amyloid matrix in the organelle for melanin deposition. Although ultimately not a component of mature fibrils, the PMEL N-terminal region (NTR) is essential for their formation. By mutational analysis we establish a high-resolution map of this domain in which sequence elements and functionally critical residues are assigned. We show that the NTR functions in cis to drive the aggregation of the downstream polycystic kidney disease (PKD) domain into a melanosomal core matrix. This is essential to promote in trans the stabilization and terminal proteolytic maturation of the repeat (RPT) domain–containing MαC units, precursors of the second fibrillogenic fragment. We conclude that during melanosome biogenesis the NTR controls the hierarchical assembly of melanosomal fibrils.

INTRODUCTION

PMEL/Pmel17/gp100 is a melanosomal transmembrane glycoprotein and clinically relevant tumor antigen specifically expressed in melanocytes and melanoma (Theos et al., 2005; Dimberu and Leonhardt, 2011). After migration into melanosomes, its cellular function is to assemble into a fibrillar matrix that serves for the deposition of the pigment melanin (Theos et al., 2005) and likely the sequestration of toxic reaction intermediates of the melanin synthesis pathway (Fowler et al., 2006). Like other amyloids, PMEL-derived aggregates may exert cellular toxicity if they form in an aberrant manner (Watt et al., 2011). Therefore it is important to understand how PMEL amyloid formation is controlled physiologically in space and in time within melanocytic cells to avert toxicity. Such controls might provide a model by which to distinguish functional from pathogenic amyloid.

A key to understanding the control of PMEL amyloid formation is delineating its biosynthetic pathway and sequential proteolytic maturation in distinct secretory and endocytic compartments (Figure 1A). After insertion into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane in the so-called P1 form, PMEL is exported to the Golgi apparatus where its N-linked oligosaccharides mature and additional O-linked glycosylation is added (Theos et al., 2005). The resulting P2 form is then processed by a proprotein convertase into two disulfide-linked fragments: an N-terminal lumenal Mα fragment and a C-terminal membrane-integrated Mβ fragment (S1 cleavage; Berson et al., 2003; Leonhardt et al., 2011). In this form (Mα-S-S-Mβ) PMEL migrates further to early-stage melanosomes, a special class of multivesicular endosomes (Raposo et al., 2001). There the protein transfers from the limiting membrane to intralumenal vesicles (ILVs) in a process dependent on the tetraspanin CD63 (van Niel et al., 2011). Further, PMEL undergoes a processing cascade involving first a membrane-proximal cleavage by a metalloprotease of the a disintegrin and metalloprotease (ADAM) family (S2 cleavage), followed by a second intramembrane cleavage by γ-secretase (S3 cleavage; Kummer et al., 2009). These processes produce a soluble lumenal Mα form, which is then cleaved into an N-terminal MαN and a C-terminal MαC fragment (Hoashi et al., 2006). MαN comprises the N-terminal region (NTR) and the polycystic kidney disease–like domain (PKD), and the eventual truncation of the NTR from this precursor liberates the PKD-containing fibrillogenic fragment (Watt et al., 2009). MαC also undergoes further processing, resulting in a ladder of fibril-associated fragments containing the repeat domain (RPT; Hoashi et al., 2006; McGlinchey et al., 2009). Both types of fibrillogenic fragment finally assemble into a matrix of amyloid sheets onto which the pigment melanin is deposited (Theos et al., 2005; Hurbain et al., 2008). Figure 1A shows a detailed schematic representation of PMEL maturation.

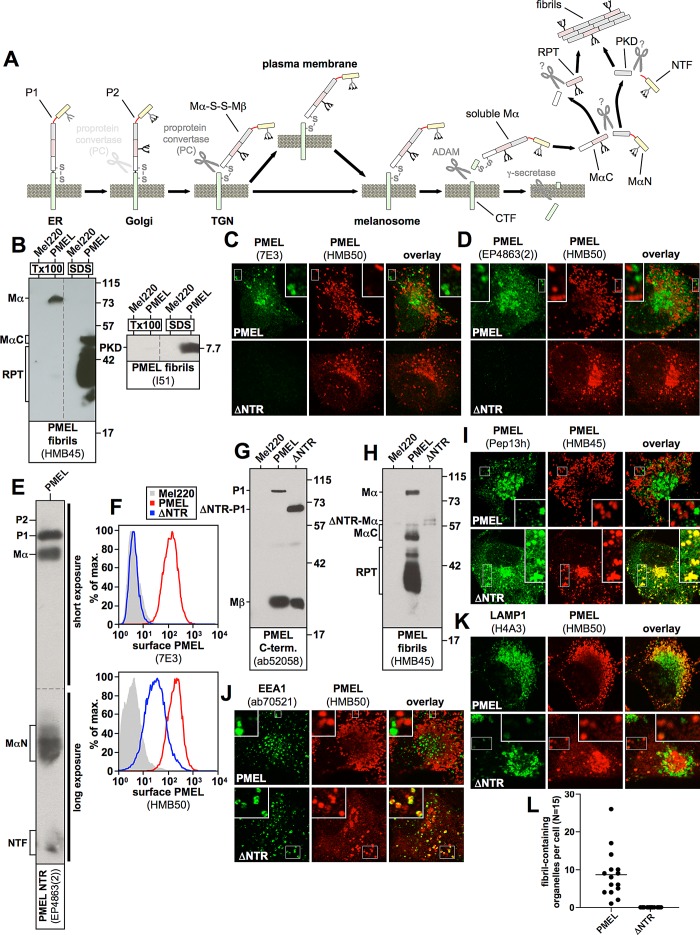

FIGURE 1:

(A) The PMEL maturation pathway. PMEL is inserted into the endoplasmic reticulum membrane in the so-called P1 form. After its release into the Golgi apparatus, N-linked oligosaccharides mature, and additional O-linked glycosylation is added, giving rise to the P2 form. Starting in the medial Golgi or in the trans-Golgi network, PMEL undergoes cleavage by a proprotein convertase, which separates the luminal fragment Mα from the membrane-standing fragment Mβ (S1 cleavage). These fragments, however, remain linked to each other by a disulfide bridge. In this form (Mα-S-S-Mβ) the protein is, either directly or via the plasma membrane, delivered into stage I melanosomes, which represent a specialized multivesicular early endosome. PMEL is originally targeted to the limiting membrane of this organelle but subsequently buds into the interior in a process dependent on the tetraspanin CD63. Next a metalloprotease of the ADAM family liberates the soluble Mα fragment from the membrane (S2 cleavage), and the remaining truncated portion of Mβ (called the CTF fragment) is degraded by γ-secretase (S3 cleavage). After this, Mα is cleaved by an unknown protease between the PKD and the RPT domain, giving rise to two halves—the N-terminal fragment, MαN, and the C-terminal fragment, MαC. Both MαN and MαC undergo further processing, which eventually liberates the PKD-containing fibrillogenic fragment, as well as a ladder of fibril-associated fragments containing the RPT domain. These two types of fragments assemble into the characteristic PMEL fibrils. The NTR is not or only to a minor extent part of the fibrils. (B) MαC, the mature RPT domain, and the mature PKD are distributed in the fibril-containing Triton X-100–insoluble fraction. Cells were extracted in 2% Triton X-100 for 1 h and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 10 min before supernatant was removed and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and Western blotting (left lanes labeled Tx100 in both blots). The Triton X-100–insoluble pellet was resuspended in PBS/1% SDS/1% β-mercaptoethanol and incubated for 10 min at room temperature, followed by 10 min at 100°C, and analyzed on the same gel (right lanes labeled SDS in both blots). Vertical dashed lines indicate where irrelevant lanes have been removed from the image. (C, D) The indicated cell lines were analyzed by IF using antibodies against PMEL fibrils (HMB50) and either antibody 7E3, raised against full-length recombinant PMEL (C), or antibody EP4863(2), raised against a peptide located within the first 100 amino acids of the PMEL NTR (D). Note that both 7E3 and EP4863(2) do not recognize the NTR deletion mutant ΔNTR, display a staining pattern limited to the ER, Golgi, and endosomes (but not stage II melanosomes), and fail to colocalize with HMB50-reactive fibrils. (E) Western blot analysis of a lysate derived from PMEL-expressing Mel220 cells. Note that antibody EP4863(2) specifically recognizes PMEL fragments that contain the NTR, such as P1, P2, Mα, MαN, and NTF. (F) The indicated transfectants were surface labeled with antibody HMB50 against folded PMEL (bottom) or PMEL-specific antibody 7E3 (top) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Note that antibody 7E3 does not recognize construct ΔNTR. (G, H) Western blot analysis of SDS-lysed total membranes using PMEL-specific antibodies ab52058 (G) and HMB45 (H). (I–K) The indicated cell lines were analyzed by IF using antibodies against newly synthesized (Pep13h) and mature (HMB45) PMEL (I), the early endosomal marker EEA1 (ab70521) and mature PMEL (HMB50; J), or the lysosomal marker LAMP1 (H4A3) and mature PMEL (HMB50; K). Note that the HMB45/HMB50-reactive population of ΔNTR but not of wt-PMEL colocalizes with the respective newly synthesized, Pep13h-reactive population (I) partially in endosomes with intense peripheral EEA1 decoration (J; see Supplemental Table S1). Only mature wt-PMEL distributes into the characteristic melanosomal horseshoe-shaped band wrapping around the perinuclear LAMP1high zone (K). (L) Quantification of the EM analysis of Epon-embedded Mel220 transfectants showing the number of fibril-containing organelles per cell (n = 15).

It has been proposed that the main role of the ∼200–amino acid–long NTR is to control the correct trafficking and processing of PMEL, although the underlying mechanism is not understood. Deletion mutants lacking the NTR do not display detectable levels of any of the fragments downstream of Mα at steady state and form no fibrils at all (Hoashi et al., 2006; Harper et al., 2008; Leonhardt et al., 2010). Moreover, such mutants are not found in lysosomal-associated membrane protein (LAMP)–containing compartments but instead distribute into early endosomes or localize to the Golgi apparatus (Hoashi et al., 2006; Theos et al., 2006; Leonhardt et al., 2010). Which subregion(s) or individual residues within the NTR are required for PMEL function is an open question. Whether the NTR is directly involved in fibril assembly, as the description of the amyloidogenic potential of this domain in vitro may suggest (Watt et al., 2009), is also not known. Moreover, how PMEL senses when it is the right time to undergo a proteolytic cascade and assemble the resulting fragments into melanosomal fibrils is essentially unclear, as is the question of how, on a mechanistic level, a molecule that appears so unremarkable in secretory compartments initiates the switch into such a massively aggregating form and how this aggregation is eventually controlled. There appears to be an emerging theme in which proteins with amyloidogenic properties often seem to contain regulatory domains, some taming, some driving their potential for aggregation (Landreh et al., 2012). Which role the major domains in PMEL—the NTR, the PKD, and the RPT domain—play in amyloid formation is highly controversial (McGlinchey et al., 2009; Watt et al., 2009); specifically, whether any of these domains has a regulatory function in the aggregation process is unknown.

To address these issues and to analyze the function of the NTR, we targeted the entire domain with sequential deletions, alanine-scanning mutagenesis, and eventually single–amino acid exchanges. Our extensive mapping data allow for the first time the construction of a high-resolution functional map in which critical sequence elements are assigned to defined mutant phenotypes. Of most interest, our results identify at least four crucial amino acids that are absolutely essential for functional fibril formation and whose replacement results in defects comparable to those observed with deletion of the entire NTR. Surprisingly, the respective mutants appear to traffic normally in the cell and even undergo proteolytic maturation into most fragments downstream of Mα. However, these fragments, including the mature PKD-containing fibrillogenic fragment and MαC, are highly unstable and instead of aggregating into fibrils, are rapidly degraded. We further demonstrate that whereas aggregation of the PKD requires it to be physically associated with a functional NTR in cis, stability can be conferred onto MαC via provision of a functional NTR–PKD unit in trans, showing for the first time that the two types of fibrillogenic fragments can be provided from separate constructs for assembly in vivo. Our results suggest a key role for the NTR in hierarchically controlling the amyloidogenesis of PMEL by driving the PKD-containing fibrillogenic fragment into a core matrix, which in turn allows the secondary incorporation of otherwise unstable MαC to form nascent fibrils. Hence consistent with the study by Watt et al. (2009), we propose that the core amyloid-forming unit in PMEL is the PKD and that this domain is sandwiched between two regulatory modules, the NTR and the RPT domain. The NTR, in this scenario, appears to be a proamyloidogenic driver seeding the amyloid aggregate before being removed by proteolysis, whereas the RPT domain is not necessary for amyloid formation as such but appears to control, organize, or tame the nascent aggregate.

RESULTS

The N-terminal region of PMEL is essential for the formation of melanosomal fibrils

PMEL is essential for the proper development of melanosomes in that it forms the fibrillar amyloid matrix, which provides these organelles with their characteristic striated appearance. The fibrils, which serve for the deposition of the pigment melanin, mainly consist of the liberated PKD and a population of fragments containing the RPT domain, the longest of which is called MαC (Hoashi et al., 2006; Watt et al., 2009). In cell extracts these fibril-associated fragments are largely distributed in the Triton X-100–insoluble fraction (Figure 1B, lane 4; Watt et al., 2009), whereas their precursor form Mα, from which the NTR has not yet been released, is, at least in Mel220 cells, largely soluble in this detergent (Figure 1B, left, lane 2). This suggests that Mα is mostly outside the amyloid aggregate, and because all other PMEL forms and fragments that contain the NTR (P1, P2, MαN, NTF; see Figure 1A) are either not localized to melanosomes (P1, P2; Leonhardt et al., 2011) or are present only at negligible amounts in the cell (P2, MαN, NTF; Leonhardt et al., 2011; see also later in Figure 7A, middle panel), it seems that the NTR is not itself part of the fibrils. This view is consistent with the lack of reactivity of fibrillar material in stage II melanosomes with an antibody recognizing the PMEL N-terminus (Watt et al., 2009). Moreover, for our present study we examined two further PMEL-specific antibodies, 7E3 and EP4863(2), both reacting with the NTR as judged by immunofluorescence (IF; Figure 1, C and D), Western blotting (Figure 1E), and flow cytometry (Figure 1F). As expected for a reagent recognizing the NTR (Leonhardt et al., 2010), both of these antibodies label PMEL in the ER, the Golgi, and endosomes, and this pattern does not colocalize with melanosomal fibrils, which are reactive with antibody HMB50 (Figure 1, C and D). Thus the NTR does not appear to be a major part of the fibrillar aggregate. Nevertheless, research has clearly demonstrated that the formation of the fibrils essentially requires this N-terminal domain (Hoashi et al., 2006; Theos et al., 2006; Leonhardt et al., 2010; Figure 1, G–L), raising the question of which role it plays in the assembly of the amyloid. In particular, the deletion of the NTR from PMEL, as in construct ΔNTR (Δ28–208) (Leonhardt et al., 2010), results in a molecule that still undergoes proprotein convertase–mediated processing (note that construct ΔNTR is cleaved into fragments Mα and Mβ; Figure 1, G and H; Leonhardt et al., 2010), but at steady state no RPT domain–containing, fibril-associated fragments downstream of Mα (fragments MαC and mature RPT) are detected by Western blotting (Figure 1H; Leonhardt et al., 2010). In respective immunoblots, antibodies against the C-terminus of the protein (Pep13h or ab52058) can serve to roughly assess the total protein expression levels, as these reagents react only with newly synthesized PMEL forms (ER-associated P1, very low levels of Golgi-associated P2, and Golgi/post-Golgi–associated Mβ; Harper et al., 2008; Leonhardt et al., 2011) but not with long-lived fibrils. Moreover, the sum of P2 and Mβ indicates how much protein is present in post-ER compartments (Golgi, trans-Golgi network [TGN], plasma membrane, and the endocytic system) at steady state. Fibril-associated fragments (MαC, RPT, PKD) are the predominant species detected by antibodies such as HMB45 or I51 (Figure 1, B and H), although these reagents also detect earlier PMEL forms (e.g., Mα) to a significant but lower extent in Western blots.

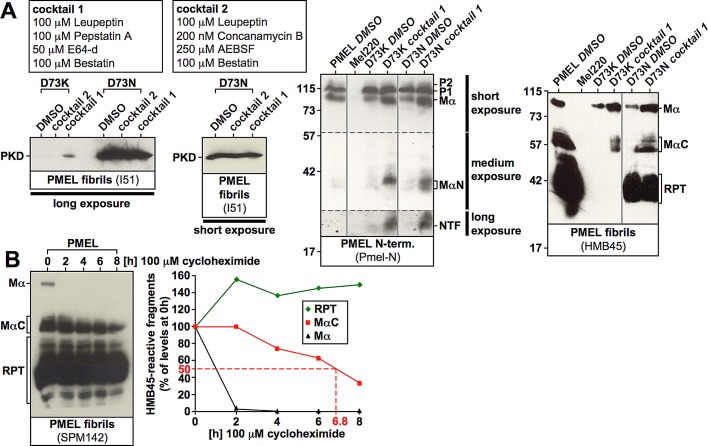

FIGURE 7:

Proteolytic processing proceeds largely normally in NTR mutants. (A) Cells expressing nonfunctional D73K (see Figure 6B) or partially functional D73N (see Figure 6B and Supplemental Figure S6A, 11A and 11B) were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide or either of two protease inhibitor cocktails for 6.5 h before total membranes were prepared, lysed in SDS, and analyzed by Western blot using the PMEL-specific antibodies I51, Pmel-N, and HMB45. A long and a short exposure of the same I51-stained blot are shown to the left. Vertical solid lines indicate positions where irrelevant lanes have been removed from the image. Horizontal dashed lines separate different exposures of the same blot. (B) Cells expressing wt-PMEL were treated with 100 μM cycloheximide for up to 8 h, and SDS-lysed total membranes were analyzed by Western blot using the antibody SPM142, which recognizes the RPT domain (left). Band intensities were determined densitometrically (right).

IF provides an indirect means to determine whether fibrils are formed in a cell. This approach takes advantage of a characteristic property of fibril-reactive antibodies such as HMB45, HMB50, or NKI-beteb, which is that these reagents practically only decorate fibrils (or other PMEL aggregate structures) in stage II melanosomes in this application, whereas labeling of earlier compartments (ER, Golgi, TGN, stage I melanosomes) is almost completely undetectable (Harper et al., 2008). The phenomenon probably reflects the extremely high density of epitopes on fibrils, which essentially depletes significant labeling from much less concentrated early protein (Harper et al., 2008). As a consequence, in IF, newly synthesized, Pep13h-reactive PMEL does not colocalize with mature, HMB45-reactive PMEL (Figure 1I; Harper et al., 2008). In contrast, mutants that fail to form fibrils, such as ΔNTR, display almost 100% colocalization of their Pep13h- and HMB45-reactive populations outside the ER (HMB45 requires sialylation of its cognate epitope in the Golgi for recognition; Figure 1I). For similar reasons, HMB50-reactive wild type (wt)-PMEL does not colocalize at all in the cell with the early endosomal marker early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1), a protein also associated with stage I melanosomes (Raposo et al., 2001), whereas mutants that fail to form fibrils, such as ΔNTR, show a significant fraction of the HMB50-reactive pool inside compartments ringed with EEA1 (Figure 1J). As described previously (Hoashi et al., 2006; Theos et al., 2006; Leonhardt et al., 2010), ΔNTR preferentially sorts into compartments containing no or only low levels of LAMP1 (Figure 1K), whereas wt-PMEL localizes to a characteristic horseshoe-shaped melanosomal pattern wrapping around and largely segregating from perinuclear LAMP1-positive lysosomes (Figure 1K; Leonhardt et al., 2010)). Fibril formation can, of course, also be assessed directly by electron microscopy (EM), which, in line with earlier reports (Hoashi et al., 2006; Theos et al., 2006), clearly demonstrates the absence of fibrils in ΔNTR-expressing cells (Figure 1L).

Three clusters of amino acids in the NTR are essential for PMEL-mediated fibril formation

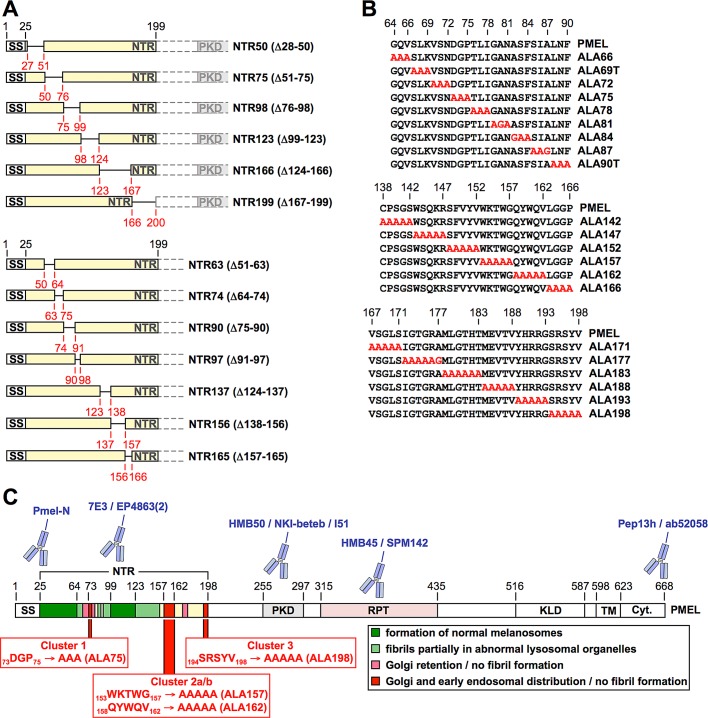

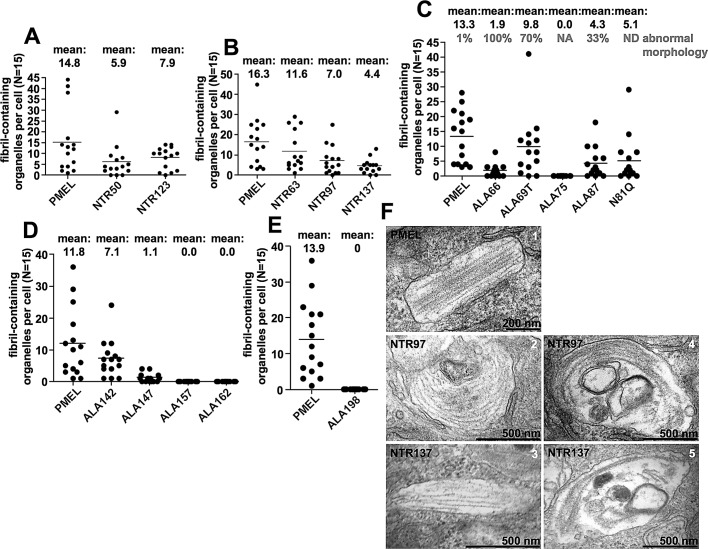

To understand the functional role of the NTR during melanosomal biogenesis, we targeted this domain with deletions (Figure 2A), followed by alanine-scanning mutagenesis of small groups of amino acids in critical regions (Figure 2B). Transfection of the respective constructs into Mel220 cells resulted in total expression levels similar to what was observed for wt-PMEL (Supplemental Figure S1A and Figure 4A later in the paper), but when bulk transfectant cultures are analyzed by the assays introduced in Figure 1, G–L, the interpretation of the results should take into consideration that expression levels may vary to some extent among individual transfectant cells. Mutant phenotypes fell into the categories indicated in Figure 2C and Table 1. As indicated by quantitative electron microscopy (Figure 3, A and B, Supplemental Figure S2B, panels 1–3) and immunoblotting for fibril-associated fragments (Supplemental Figure S1, B and C), deletion of the largely dispensable regions 28–63 and 99–123, color coded in dark green in Figure 2C, resulted at most in a modest reduction in fibril formation (constructs NTR50, NTR63, and NTR123). Directly flanking these areas (coded in light green in Figure 2C), we found sequences (roughly covering residues 64–69, 85–98, and 124–147) that, when mutationally targeted, caused moderately to severely reduced fibril formation (Figure 3, B–D) and fibril deposition in both regular ellipsoid melanosomes, as well as in abnormal organelles with a more lysosomal appearance (prototype mutants NTR97 and NTR137 in Figure 3F, compare 1–3 to 4 and 5; and mutants ALA69T, ALA87, ALA142, and ALA147 in Supplemental Figure S2B, compare panels 4–8 to 9–14). The latter abnormal organelles were more spherical in shape and often contained extensive multilamellar membrane accumulations. Immunofluorescence analysis showed that the respective mutants also segregated inefficiently from lysosomal LAMP1high zones (phenotypes B and C in Supplemental Figure S2A), although only in a subset of cells, and instead of subcellularly distributing into the characteristic melanosomal horseshoe-shaped pattern (Leonhardt et al., 2010; phenotype A in Supplemental Figure S2A), the protein was often found in the perinuclear area where typically lysosomes reside in Mel220 cells (Leonhardt et al., 2010). This suggests that either the respective constructs missort in the cell or melanosomes fail to maintain their typical segregation from the lysosomal system. In flow cytometry or IF, these constructs reacted normally (in terms of intensity) with antibodies that mainly recognize fibrils in these applications (Supplemental Figures S2, A and C, and S3, A, C, and E; unpublished data; and Supplemental Table S1), whereas the levels of fibrillogenic fragments appeared sharply reduced when assessed by Western blot (see prototype mutants NTR97 and NTR137 in Supplemental Figure S1, B and C, and Figure 4, B and C). Given our earlier experience with PMEL mutants such as IR-wt and H190P (Leonhardt et al., 2010), this likely reflects the formation of irregular lysosomal aggregates, which inefficiently enter SDS gels but react well with antibodies in intact cells. Of interest, in mutant N81Q, the lack of the N-linked glycan on asparagine-81, the only NTR-associated glycan that does not acquire EndoH resistance during secretion of the molecule (Hoashi et al., 2010), caused an identical phenotype with inefficient segregation from LAMP1high compartments (Supplemental Figure S1D) and fibril deposition partially in abnormal lysosomal organelles (Supplemental Figure S2B, compare panels 6 and 12). Thus, since the other two N-linked glycans in the NTR (at asparagines 106 and 111) are located within a region that is largely dispensable (see mutant NTR123 in Figure 3A and Supplemental Figures S1, A–C, S2, A and B, panel 3), asparagine-81 appears to be the only glycan in the N-terminus that has significant functional relevance. Targeting regions 70–72, 76–81, and 172–177 (color coded in pink in Figure 2C) with alanine-scanning mutagenesis largely resulted in Golgi retention of PMEL and no or very low levels of protein migrating further into the endocytic system (see mutants ALA72, ALA78, ALA81, and ALA177 in Supplemental Figures S1E and S3, B, D, and F).

FIGURE 2:

A functional map of the PMEL NTR. (A, B) Schematic representation of PMEL NTR deletion (A) and alanine-scanning (B) mutants. (C) Domain organization of PMEL and functional map of the NTR. This figure summarizes the findings shown in Figures 3 and 4 and Supplemental Figures S1–S3. The color code indicates largely dispensable regions in the NTR (dark green) and regions that when mutationally targeted cause at least partial deposition of fibrils in lysosomes (light green), Golgi retention (pink), or the phenotype observed with deletion of the entire NTR (red). Regions that when targeted by alanine-scanning mutagenesis resulted in ER retention and strongly reduced reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibodies such as HMB50 are shown in yellow. Clusters 1–3, which were subsequently targeted by single-alanine exchanges, are highlighted. PMEL-specific antibodies used in this study are pictographically assigned to the domains that they recognize. See also Table 1 and Supplemental Table S1.

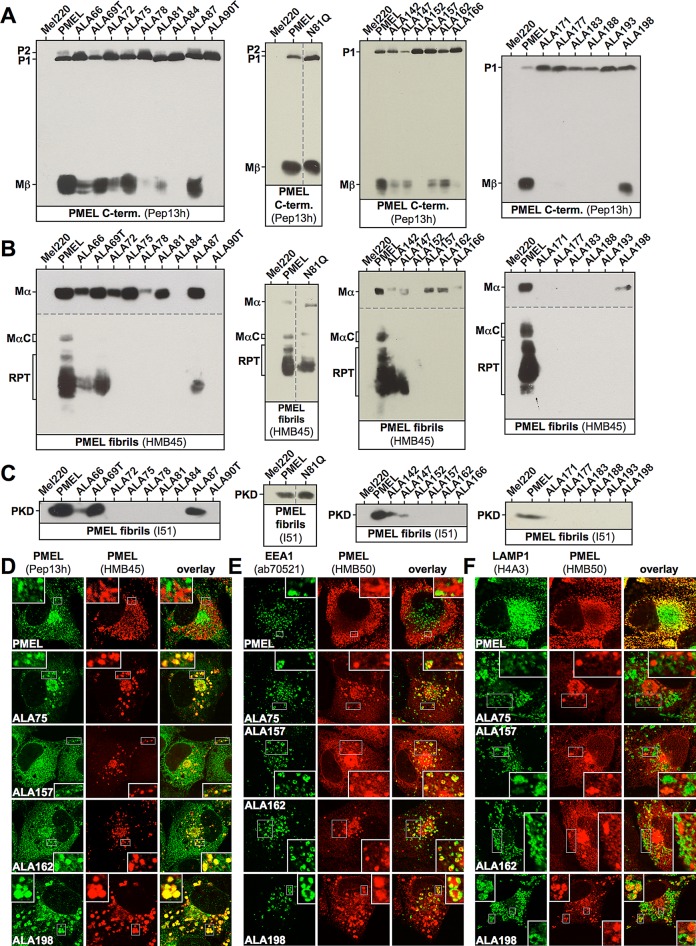

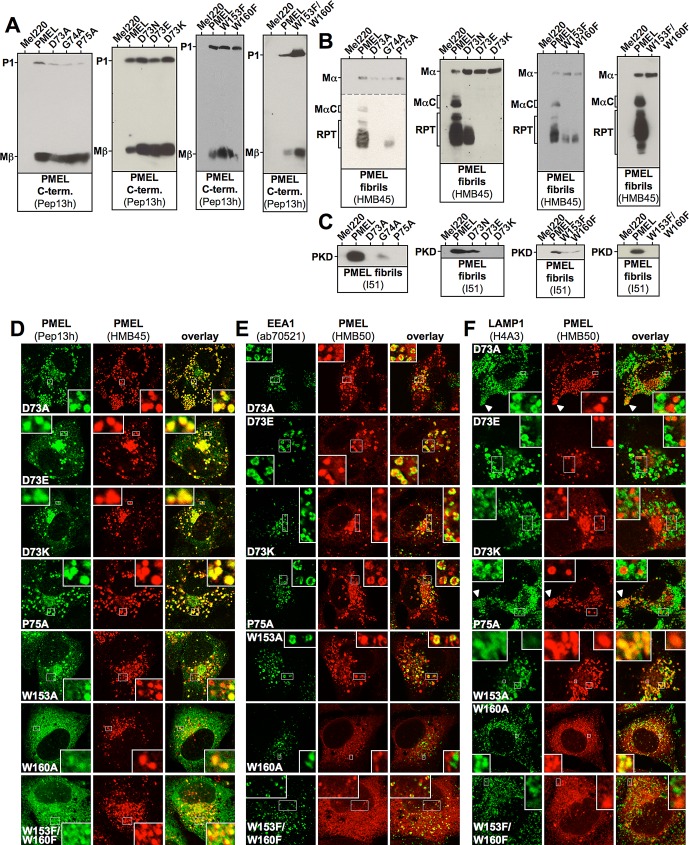

FIGURE 4:

Proteolytic maturation and subcellular distribution of PMEL NTR alanine-scanning mutants. (A–C) Western blot analysis of SDS-lysed total membranes using PMEL-specific antibodies Pep13h (A), HMB45 (B), and I51 (C). Vertical dashed lines indicate positions where irrelevant lanes have been removed from the image. Horizontal dashed lines separate different exposures of the same blot. (D–F) Selected cell lines from A–C were analyzed by IF using antibodies against newly synthesized (Pep13h) and mature (HMB45) PMEL (D), the early endosomal marker EEA1 (ab70521) and mature PMEL (HMB50; E), or the lysosomal marker LAMP1 (H4A3) and mature PMEL (HMB50; F). Note that the HMB45/HMB50-reactive population of the indicated alanine-scanning mutants but not of wt-PMEL colocalizes with the respective newly synthesized, Pep13h-reactive population (D) partially in endosomes with intense peripheral EEA1 decoration (E; see Supplemental Table S1). Only mature wt-PMEL distributes into the characteristic melanosomal horseshoe-shaped band wrapping around the perinuclear LAMP1high zone (F). The corresponding IF data for the other mutants in A–C are shown in Supplemental Figures S3 and S1, D and E.

TABLE 1:

Summary of the phenotypes of PMEL deletion and alanine-scanning mutants.

| Mutant | Description | Category |

|---|---|---|

| NTR50 | Δ28-50 | Formation of normal melanosomes (indistinguishable from wt-PMEL) |

| NTR63 | Δ51-63 | Formation of normal melanosomes (indistinguishable from wt-PMEL) |

| NTR123 | Δ99-123 | Formation of normal melanosomes (indistinguishable from wt-PMEL) |

| NTR97 | Δ91-97 | Fibril deposition in both normal melanosomes and lysosomal organelles |

| NTR137 | Δ124-137 | Fibril deposition in both normal melanosomes and lysosomal organelles |

| ALA66 | 64GQV66→AAA | Fibril deposition only in lysosomal organelles |

| ALA69T | 67SLK69→AAA | Fibril deposition in both normal melanosomes and lysosomal organelles |

| ALA87 | 85SIA87→AAG | Fibril deposition in both normal melanosomes and lysosomal organelles |

| ALA142 | 138CPSGS142→AAAAA | Fibril deposition in both normal melanosomes and lysosomal organelles |

| ALA147 | 143WSQKR147→AAAAA | Fibril deposition in both normal melanosomes and lysosomal organelles |

| ALA166 | 163LGGP166→AAAA | Not analyzed by EM, but IF shows all mature protein in LAMP1high lysosomes |

| ALA72 | 70VSN72→AAA | Golgi retention/no fibril formation |

| ALA78 | 76TLI78→AAA | Golgi retention/no fibril formation |

| ALA81 | 79GAN81→AGA | Golgi retention/no fibril formation |

| ALA177 | 172IGTGRA177→AAAAAG | Golgi retention/no fibril formation |

| ALA75 | 73DGP75→AAA | Golgi and early endosomal distribution/no fibril formation |

| ALA157 | 153WKTWG157→AAAAA | Golgi and early endosomal distribution/no fibril formation |

| ALA162 | 158QYWQV162→AAAAA | Golgi and early endosomal distribution/no fibril formation |

| ALA198 | 194SRSYV198→AAAAA | Golgi and early endosomal distribution/no fibril formation |

| NTR75 | Δ51-75 | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| NTR98 | Δ76-98 | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| NTR166 | Δ124-166 | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| NTR199 | Δ167-199 | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| NTR74 | Δ64-74 | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| NTR90 | Δ75-90 | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| NTR156 | Δ138-156 | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| NTR165 | Δ157-165 | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| ALA84 | 82ASF84→GAA | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| ALA90T | 88LNF90→AAA | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| ALA152 | 148SFVYV152→AAAAA | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| ALA171 | 167VSGLS171→AAAAA | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| ALA183 | 178MLGTHT183→AAAAAA | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| ALA188 | 184MEVTV188→AAAAA | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

| ALA193 | 189YHRRG193→AAAAA | Complete ER retention/minimal reactivity with conformation-sensitive antibody HMB50 |

The phenotypes of the PMEL deletion and alanine-scanning mutants (Figure 2, A and B) generated in this study fell into the five indicated categories. Figure 2C maps the respective phenotypes onto a pictogram of the NTR. The color code corresponds to the color code used in Figure 2C.

FIGURE 3:

Fibril formation by PMEL NTR deletion and alanine-scanning mutants. (A–E) Quantification of the EM analysis of Epon-embedded Mel220 transfectants showing the number of fibril-containing organelles per cell (n = 15). (F) EM images for mutants NTR97 and NTR137. The quantification of fibril formation shown in A–E is based on images like these and those shown in Supplemental Figure S2B. Note that mutants NTR97 and NTR137 form fibrils in both conventional melanosomes (left) and abnormal organelles sharing lysosomal characteristics (right).

Strikingly, four mutants—ALA75, ALA157, ALA162, and ALA198—in which regions henceforth referred to as clusters 1 (73–75), 2 (153–162), and 3 (194–198; color coded red in Figure 2C) had been targeted, closely mimicked the phenotype observed after deletion of the entire NTR (Figure 1, G–L; Leonhardt et al., 2010). These mutants did not form either type of fibrillogenic fragment, reactive with antibody I51 (PKD) or HMB45 (RPT domain), respectively (Figure 4, B and C). However, as shown by perinuclear accumulation of Pep13h- and HMB45-specific signal (Figure 4D) and overlap of HMB50-specific labeling with the Golgi marker GM130 (Supplemental Figure S1E and unpublished data), they produced a robust Golgi population. In addition, overlap of HMB50-specific labeling with EEA1 demonstrates that they migrated into early endosomes to a significant extent (Figure 4E). ALA198 displayed a particularly prominent endosomal pattern, whereas Golgi labeling was somewhat lower compared with the other constructs. In endosomes, a very substantial colocalization between the pool of newly synthesized protein, reactive with antibody Pep13h, and the pool of mature protein, reactive with the antibody HMB45, was observed, resulting in an almost complete overlap of the two populations in many cells (Figure 4D, bottom four rows). This was never seen in wt-PMEL–expressing transfectants (Figure 4D, top row) and strongly indicates the absence of fibrils and aggregates in the respective cells (see notes on antibodies HMB45, HMB50, and NKI-beteb in Supplemental Table S1). The endosomal protein detected by HMB45 was likely Mα, as this was the only HMB45-reactive form detected in Western blots (Figure 4B). When cells were colabeled with antibodies against PMEL and EEA1, we observed significant colocalization in early endosomes, with the peripheral EEA1 protein forming rings around many of the HMB50-positive compartments (Figure 4E, bottom four rows). Again, no such distribution was seen for wt-PMEL (Figure 4E, top row). Colocalization in the endocytic system between EEA1 and NTR mutants (HMB50) was often weaker than colocalization between the respective newly synthesized (Pep13h) and mature (HMB45) proteins, indicating that a substantial fraction of these mutants might localize to recycling endosomes. Moreover, these mutants were often found in compartments that contained either no or only low levels of the lysosomal marker LAMP1 (Figure 4F, right insets). Only ALA198 displayed a more substantial overlap with LAMP1, but, of interest, colocalization was typically limited to peripheral regions, particularly membrane extensions (Figure 4F, bottom row, left upper inset) and did not occur in the perinuclear area, where conventional lysosomes or aberrant fibril-containing organelles reside (Supplemental Figure S2A; Leonhardt et al., 2010). When analyzed by EM, fibril formation was completely abrogated in transfectants expressing ALA75, ALA157, ALA162, or ALA198 (Figure 3, C–E).

Asp73, Pro75, Trp153, and Trp160 are essential for fibril formation

Next we mapped the functional requirement for the NTR in fibril formation to individual amino acids. To this end, we exchanged every residue within the functionally crucial clusters 73–75, 153–162, and 194–198 individually to alanine. Of interest, despite the predicted mild nature of single–amino acid replacements, many mutants (G74A, K154A, T155A, W156A, G157A, Q158A, Y159A, Q161A, and V162A) showed defects very reminiscent of the phenotypes observed with the deletion constructs NTR97 and NTR137 (Figures 5, A–C, and 6, A, D, and E, and Supplemental Figures S4, S5, and S6A). Besides often displaying a poor subcellular segregation from lysosomal LAMP1high compartments (see G74A in Supplemental Figure S4F and various constructs in Supplemental Figure S5C), they formed fibrils in both morphologically normal (Supplemental Figure S6A, column A) and morphologically aberrant organelles (Supplemental Figure S6A, column B), indicating that the targeted regions as a whole may be functionally relevant to some extent. In contrast, all cluster 3 mutants (S194A, R195A, S196A, Y197A, and V198A) behaved very similar to wt-PMEL, displayed at most a mildly affected processing (note, e.g., that all these mutants show significant levels of MαC at steady state in Supplemental Figure S4, A–C, right), and showed a normal subcellular distribution (Supplemental Figure S5, A–C) and largely normal fibril formation (Figure 6C and Supplemental Figure S6B).

FIGURE 5:

Trafficking and processing of selected PMEL NTR point mutants. (A–C) Western blot analysis of SDS-lysed total membranes using PMEL-specific antibodies Pep13h (A), HMB45 (B), and I51 (C). Horizontal dashed lines separate different exposures of the same blot. (D–F) Selected cell lines from A–C and Supplemental Figure S4, A–C, were analyzed by IF using antibodies against newly synthesized (Pep13h) and mature (HMB45) PMEL (D), the early endosomal marker EEA1 (ab70521) and mature PMEL (HMB50; E), or the lysosomal marker LAMP1 (H4A3) and mature PMEL (HMB50;F). The corresponding IF data for the other point mutants generated for this study are shown in Supplemental Figures S4 and S5.

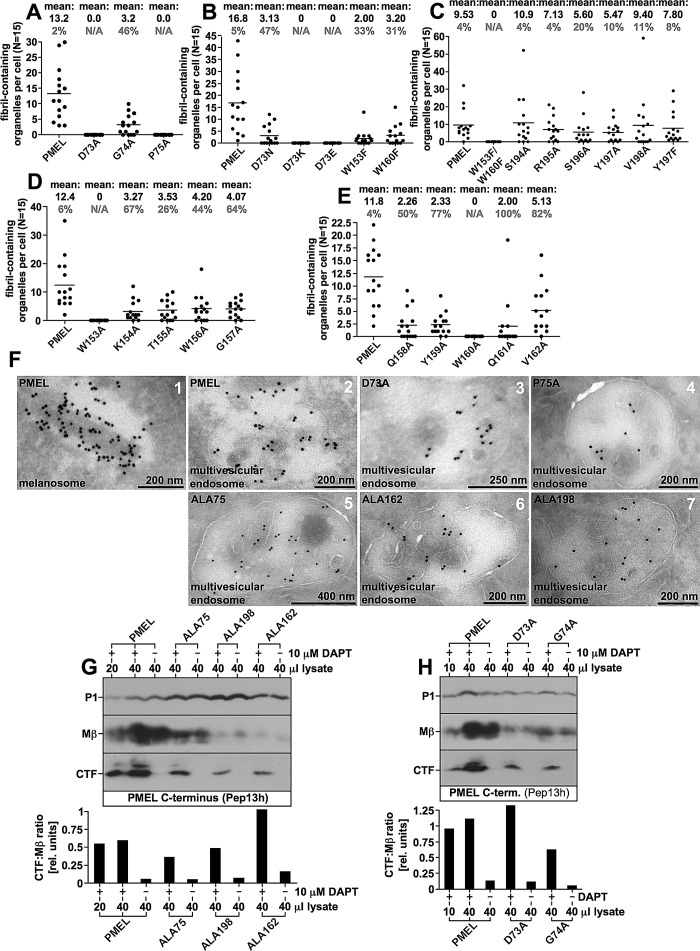

FIGURE 6:

Fibril formation, trafficking, and S2 processing of selected PMEL NTR mutants. (A–E) EM analysis of Epon-embedded Mel220 transfectants (see Supplemental Figure S6 for respective electron micrographs). Quantification of fibril formation (n = 15) is shown. Percentage abnormal organelles is shown in gray. (F) Selected NTR mutants were analyzed by cryo–immuno EM using the PMEL-specific antibody HMB45. Note the labeling on ILVs. (G, H) Selected NTR mutants were treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT or dimethyl sulfoxide for 2.5 h and analyzed by Western blot using the PMEL-specific antibody Pep13h (top). CTF:Mβ ratios were determined densitometrically and are represented as bars (bottom).

Strikingly, four of the single–amino acid exchange mutants (D73A, P75A, W153A, and W160A) mimicked the phenotype observed with the deletion of the entire NTR, indicating that the essential requirement for this domain can be mapped to a few functionally critical residues. These constructs matured properly into Mα and Mβ (only W160A showing weak ER export; Figure 5, A and B, and Supplemental Figure S4, A and B) but failed to form fibrillogenic fragments (Figure 5, B and C, and Supplemental Figure S4, B and C). Their HMB45-reactive fraction overlapped completely (D73A and P75A) or to a significant extent (W153A and W160A) with newly synthesized (Pep13h-reactive) protein (Figure 5D), further indicating lack of fibril formation. A substantial portion of the protein (except for poorly secreted W160A) localized to EEA1-positive early endosomes (Figure 5E) and preferentially sorted into LAMP1low or LAMP1-free compartments (Figure 5F). In addition, like ALA198, constructs D73A and P75A displayed some accumulation in peripheral LAMP1high compartments but were excluded from the perinuclear LAMP1high zone (Figure 5F, arrowheads), indicating that they do not migrate into conventional lysosomes (Leonhardt et al., 2010). In contrast, W153A and W160A showed substantial overlap with the perinuclear LAMP1high region (Figure 5F, rows 5 and 6, left insets), suggesting that both constructs contribute to some extent to lysosomal aggregates. Judged by EM, none of the aforementioned mutants formed fibrils (Figure 6, A, D, and E).

To assess the functional flexibility of the protein with respect to amino acids in key positions, we subjected selected crucial residues to more conservative substitutions. In particular we made six more constructs (D73N, D73E, D73K, W153F, W160F, and W153F/W160F). Three of these (D73N, W153F, and W160F) were substantially impaired in the formation of fibrillogenic fragments (Figure 5, B and C) and in fibril formation (Figure 6B) but gave rise to at least a few conventional melanosomes (Supplemental Figure S6A, 11A, 12A, and 13A) alongside mostly aberrant organelles (Supplemental Figure S6A, 11B, 12B, and 13B) with often weak fibril content. Strikingly, substitution of aspartate 73 to lysine (D73K) or even to the very closely related glutamate (D73E) completely abrogated fibril formation and recapitulated the phenotype observed with the deletion of the entire NTR (Figures 5 and 6B). Moreover, although constructs W153F and W160F retained some low degree of residual function, the combination of the two mutations completely blocked fibril formation (Figures 5 and 6C). Taken together, our data suggest that Asp73, Pro75, Trp153, and Trp160 play key roles in PMEL fibril formation and unveil a surprising inflexibility even to very conservative amino acid exchanges in these positions.

Trafficking and proteolytic maturation are largely intact in NTR mutants

Studies suggested that the NTR might be required for correct trafficking, transfer of PMEL to ILVs within early-stage melanosomes, or proper processing of the molecule (Hoashi et al., 2006; Theos et al., 2006). To investigate whether a potential trafficking or processing defect underlay the phenotypes of those mutants mimicking the loss of the entire NTR, we assessed their distribution by cryo–immuno EM using antibody HMB45 (Figure 6F). None of the investigated mutants (ALA75, ALA162, ALA198, D73A, and P75A) displayed a substantial impairment in accessing multivesicular endosomes, and they were all efficiently transferred to ILVs through intraorganellar budding (Figure 6F). Transfer of PMEL onto ILVs usually occurs in an endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)–independent manner (Theos et al., 2006; van Niel et al., 2011), but if this pathway is blocked, as in CD63-depleted cells, budding may proceed to some extent in an ESCRT-dependent manner, resulting in significant delivery of HMB50-reactive PMEL to lysosomes (van Niel et al., 2011). In this case, at least a mild accumulation of PMEL in the limiting membrane of multivesicular endosomes (MVEs) is observed (van Niel et al., 2011). Although we cannot fully exclude that the transfer of NTR mutants to ILVs in Mel220 cells occurred in an ESCRT-dependent manner, the lack of colocalization of ΔNTR and many of its derivatives (ALA75, ALA162, ALA198, D73A, and P75A) with perinuclear LAMP1 (Figures 1K, 4F, and 5F) suggests otherwise. In addition, we did not observe a general accumulation of NTR mutants in the limiting membrane of MVEs (Figure 6F). Moreover, all these mutants displayed the formation of the characteristic C-terminal fragment (CTF; see Figure 1A) in cells treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT; to block CTF degradation; Kummer et al., 2009; van Niel et al., 2011), and CTF levels were not substantially reduced when normalized to its precursor Mβ, indicating S2 cleavage to be intact (Figure 6, G and H).

To address whether processing of Mα was blocked in NTR mutants, we treated cells expressing either nonfunctional D73K or partially functional D73N (Figures 5 and 6B and Supplemental Figures S4, D–F, and S6A, 11A and 11B) with a protease inhibitor cocktail (cocktail 1, including 100 μM leupeptin, 100 μM pepstatin A, 50 μM E64-d, and 100 μM bestatin methylester). Of interest, this treatment strongly stabilized both MαN and MαC fragments in either mutant (Figure 7A, panels 3 and 4), indicating that proper processing of Mα indeed occurred, but apparently the resulting proteolytic products rapidly decay. In fact, MαC typically has a half-life of almost 7 h in the cell (Figure 7B), indicating that this fragment is abnormally unstable when generated from D73K or D73N. Strikingly, even further processing of MαN seemed to proceed, as in protease inhibitor–treated cells both the isolated NTR (NTF) and the PKD-containing fibrillogenic fragment were detectable (Figure 7A, panels 1 and 3). Thus, surprisingly, the proteolytic maturation of PMEL was found largely intact in NTR mutants. Only the conversion of MαC into the mature RPT domain–containing fibrillogenic fragments was never observed in cells expressing nonfunctional mutants such as D73K and receiving either the protease inhibitor cocktail (Figure 7A, rightmost panel) or any of the included inhibitors individually (unpublished data).

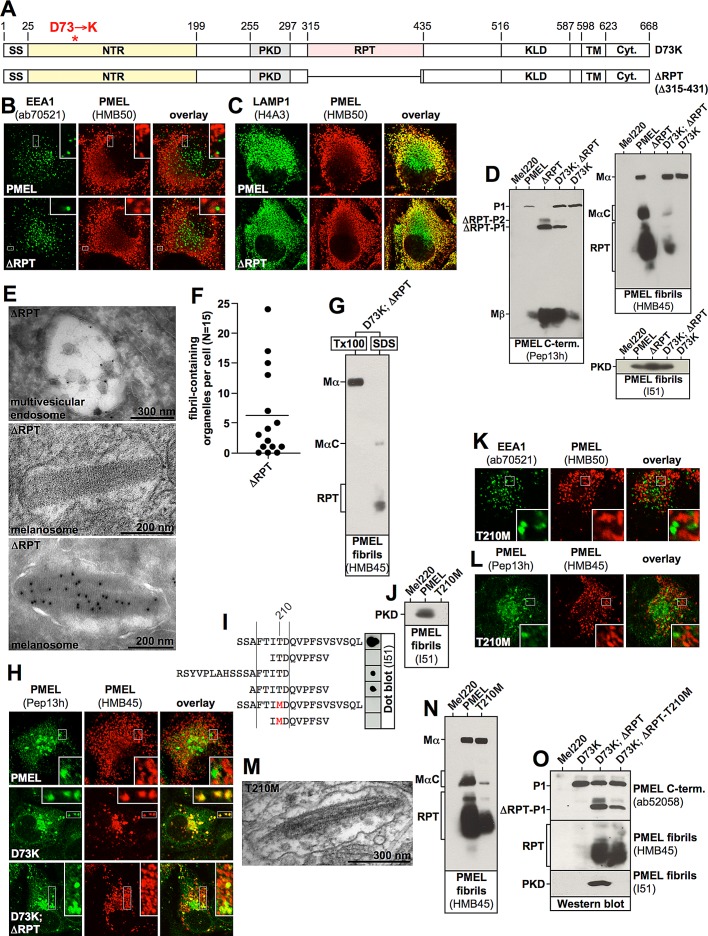

The NTR is required in cis for aggregation of the PKD-containing fibrillogenic fragment and in trans for stabilization of MαC

The impaired processing of D73K-derived MαC led us to assess whether this fragment was actually correctly formed. To this end, we used the PMEL mutant ΔRPT (Δ315–431) (Figure 8A) to transfer a functional NTR–PKD unit into cells already expressing construct D73K. When expressed alone in Mel220 cells, ΔRPT distributed into the characteristic melanosomal pattern (Leonhardt et al., 2010), a horseshoe-shaped band wrapping around and thus segregating from the perinuclear LAMP1high lysosomal area (Figure 8, B and C). Moreover, the mutant, unlike D73K, gave rise to high levels of the PKD-containing fibrillogenic fragment (Figure 8D, right bottom, lane 3). This demonstrates for the first time that the stable accumulation of this fragment requires a functional NTR, but not the RPT domain. Further, cells stably expressing ΔRPT displayed transfer of the construct to ILVs (Figure 8E, top) and formed ellipsoid melanosomes with clearly visible sheet-like aggregate content, remarkably ordered structures with a repeating pattern extending along the longitudinal axis (Figure 8, E and F, middle and bottom). This suggests that the aggregation of PMEL into an amyloid matrix does not require the RPT domain in melanoma cells (Figure 8, E and F). We note that this substantially differs from earlier findings in the HeLa cell system, in which related ΔRPT mutants had been shown to form no fibrils at all (Hoashi et al., 2006; Theos et al., 2006), suggesting that melanoma cells provide a superior environment for PMEL folding, stabilization, or fibril assembly. However, we note that ΔRPT-containing amyloid appeared to be more compact (Figure 8E) than what is observed with wt-PMEL (Figure 3F, 1, and Supplemental Figure S6A, 1A), perhaps because fibrils are more densely packed or aggregation becomes excessive or otherwise changes in nature. This may be reminiscent of some naturally occurring pathological PMEL variants, which also have been described to form very tightly packed aggregates resulting in cellular toxicity (Watt et al., 2011). Hence the role of the RPT domain in the amyloid formation process may be completely accessory in that it may control, organize, and perhaps even tame the aggregate. We note that in vivo the RPT domain is heavily O-glycosylated (Hoashi et al., 2006), which might explain why the amyloidogenic potential that McGlinchey et al. (2009) found with bacterially synthesized recombinant RPT domain is less relevant in intact cells.

FIGURE 8:

The NTR and the PKD must be provided in cis for fibril formation but can stabilize the RPT domain–containing MαC fragments in trans. (A) Schematic representation of the PMEL mutant ΔRPT. (B, C) Mel220 cells expressing wt-PMEL or ΔRPT were analyzed by IF using antibodies against the early endosomal marker EEA1 (ab70521) and mature PMEL (HMB50; B) or the lysosomal marker LAMP1 (H4A3) and mature PMEL (HMB50; C). (D) SDS-lysed total membranes derived from cells expressing wt-PMEL, ΔRPT, or D73K or coexpressing ΔRPT and D73K were analyzed by Western blot using the PMEL-specific antibodies Pep13h, HMB45, and I51. (E) Mel220 transfectants stably expressing ΔRPT were analyzed by EM (Epon-embedded cells; middle) or cryo–immuno EM using the PMEL-specific antibody HMB50 (top and bottom). (F) EM analysis of Epon-embedded Mel220 transfectants expressing ΔRPT. Quantification of fibril formation (n = 15) is shown. (G) D73K-derived MαC and mature RPT domain stabilized by a coexpressed ΔRPT construct are distributed in the Triton X-100–insoluble fibril fraction, whereas D73K-derived Mα remains Triton X-100 soluble. A total membrane fraction was extracted in 1% Triton X-100 for 1 h and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 45 min before supernatant was removed and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and Western blotting (left lane labeled Tx100). The Triton X-100–insoluble pellet was resuspended in PBS/1% SDS/1% β-mercaptoethanol and incubated for 10 min at room temperature, followed by 10 min at 100°C and analyzed on the same gel (right lane labeled SDS). (H) Cells expressing wt-PMEL or D73K or coexpressing ΔRPT and D73 were analyzed by IF using the PMEL-specific antibodies Pep13h and HMB45. (I) The indicated synthetic peptides were adsorbed to nitrocellulose membrane, and a dot blot was performed using antibody I51. Note that the exchange of threonine 210 to methionine abrogates the recognition of the peptide by the antibody (compare lane 1 to lane 5). (J) SDS-lysed total membranes derived from cells expressing wt-PMEL or T210M were analyzed by Western blot using the PMEL-specific antibody I51. (K, L) Mel220 cells expressing T210M were analyzed by IF using antibodies against the early endosomal marker EEA1 (ab70521) and mature PMEL (HMB50;K) or the PMEL-specific antibodies Pep13h and HMB45 (L). (M) Mel220 transfectants stably expressing T210M were analyzed by EM (Epon-embedded cells). (N) SDS-lysed total membranes derived from cells expressing wt-PMEL or T210M were analyzed by Western blot using the PMEL-specific antibody HMB45. (O) SDS-lysed total membranes derived from cells expressing D73K alone, coexpressing ΔRPT and D73K, or coexpressing I51-nonreactive ΔRPT-T210M and D73K were analyzed by Western blot using the PMEL-specific antibodies ab52058, HMB45, and I51.

Strikingly, when constructs D73K and ΔRPT were coexpressed, D73K-derived MαC was stabilized and in this situation also underwent the terminal proteolytic maturation into the ladder of RPT domain–containing fibril-associated fragments (Figure 8D, top right, lane 4). Both D73K-derived MαC and the D73K-derived RPT fragments distributed into the Triton X-100–insoluble fibril fraction, suggesting that these fragments partitioned into aggregates, whereas D73K-Mα remained completely Triton X-100 soluble (Figure 8G). In parallel, an HMB45-reactive D73K population arose that did not colabel with the antibody Pep13h, specific for newly synthesized protein, indicating the accumulation of mature protein (Figure 8H, bottom). Such a population is typically observed in cells expressing wt-PMEL but not in cells expressing D73K alone (Figure 8H, top and middle) and indicates that D73K-derived MαC is incorporated into fibrils or aggregates in the presence of ΔRPT. This shows not only that D73K-derived MαC is generally functional, but also that this fragment can be stabilized by an intact NTR-PKD unit in trans. Thus our results strongly suggest that the two PMEL fibrillogenic fragments can be provided via two separate constructs for assembly into fibrils in vivo.

Next we assessed whether a functional NTR–PKD unit delivered via the ΔRPT construct can also rescue the D73K-derived PKD fragment, a fragment that is made in the cell (Figure 7A, left) but is unstable. To this end, we constructed a ΔRPT variant containing the T210M mutation, which abrogates reactivity with antibody I51 (Figure 8, I and J) but not fibril formation (Figure 8, K–N). To confirm that fibril formation proceeds in the context of the T210M mutation, we first characterized full-length PMEL-T210M. The respective mutant displayed the characteristic segregation of Pep13h- from HMB45-specific signal in IF (Figure 8L) and also did not show an overlap between EEA1 and mature HMB50-reactive PMEL (Figure 8K). Of importance, the latter experiment demonstrated that the T210M-PKD accumulates in fibrils (or other aggregates), although the respective fragment is undetectable by antibody I51 (Figure 8J). When analyzed by EM, clearly, fibril-containing organelles were visible (Figure 8M), and, as expected, Western blots showed that Mα was processed into MαC and RPT (Figure 8N). Consistent with these results, ΔRPT-T210M was capable of promoting the stable accumulation of RPT domain–containing fibrillogenic fragments derived from D73K just like its parental construct ΔRPT (Figure 8O), indicating that it is functional in this sense. However, no I51-reactive PKD fragment could be detected at all in cells coexpressing D73K and ΔRPT-T210M (Figure 8O), demonstrating that the D73K mutant does not contribute its PKD for fibril formation in this stable cell line. Hence the mere provision of a functional NTR (via ΔRPT-T210M) cannot rescue an unmutated PKD (from D73K) in trans. Instead, the NTR and the PKD must be present in cis in order to sustain high levels of the PKD-containing fibrillogenic fragment, probably in the form of the aggregate matrix shown in Figure 8E in ΔRPT-expressing cells.

DISCUSSION

PMEL plays an important role in the development of melanosomes in that it forms a matrix in the organelle that is composed of fibrillar amyloid sheets for deposition of the pigment melanin (Raposo and Marks, 2007; Hurbain et al., 2008). Although the early trafficking and processing of the molecule have been extensively characterized (Berson et al., 2001, 2003; Raposo et al., 2001; Theos et al., 2005; Harper et al., 2008; Leonhardt et al., 2011), the late events driving the proteolytic maturation and aggregation of Mα into fibrillogenic fragments, and subsequently fibrils, are much less clear. In particular, how the individual domains in Mα—the NTR, the PKD, and the RPT domain—act together to form functional amyloid is controversial and not well understood (McGlinchey et al., 2009; Watt et al., 2009). In the past, the main role of the NTR had been proposed to be to control the trafficking and processing of the molecule, as well as to mediate the budding of PMEL-enriched vesicles into the lumen of multivesicular stage I melanosomes (Hoashi et al., 2006; Theos et al., 2006). However, our careful analysis of a large array of NTR-mutant PMEL variants stably expressed in melanoma cells points in a different direction. Our data suggest that although NTR mutants do indeed access multivesicular endosomes (Figure 6F), transfer to intralumenal vesicles (Figure 6F), and undergo a largely intact proteolytic maturation (Figures 4, A and B, and 5, A and B [proprotein convertase cleavage], and Figures 6, G and H [S2 and S3 cleavage], and 7A [subsequent cleavages]), they fail to stabilize the resulting fibrillogenic fragments and are degraded rather than assemble into fibrils (Figures 7A and 8, D, H, and O). In particular, we identify a hierarchical cascade in which the NTR first sustains in cis high cellular levels of the PKD-containing fibrillogenic fragment, probably in the form of an amyloid-type aggregate (Figure 8, B–F). This process is essential for subsequently stabilizing in a second step the RPT domain–containing MαC fragment in trans (Figure 8, D, G, H, and O).

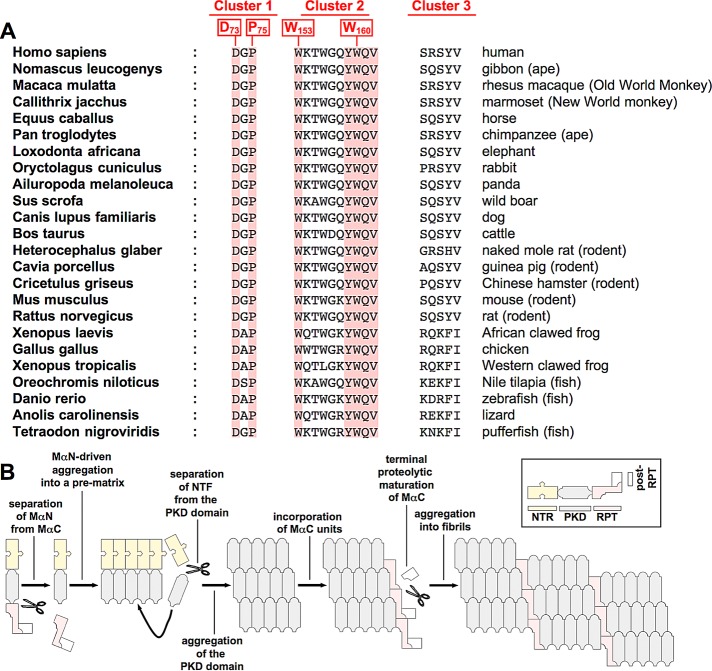

We also identified the critical amino acids and regions in the NTR that are essential for fibril formation (see also Figure 2C). A closer look at their sequence context (73DGP75, 153WKTWGQYWQV162, and 194SRSYV198; essential residues in bold), shows that all three clusters contain at least one charged amino acid, and the second and third clusters additionally contain multiple polar residues, suggesting that the respective side chains face outward from the protein surface rather than point inward to the hydrophobic protein core. Thus these clusters are likely to be accessible from the outside and possibly involved in intramolecular or intermolecular interactions. Of interest, amino acids involved in interactions at protein–protein interfaces are not randomly distributed, and this is particularly true for residues that make key contributions to such interactions (so-called “hot spots,” defined as sites where alanine mutations substantially diminish the respective protein–protein binding). The amino acids most strongly enriched in hot spots are, in this order, tryptophan (W), arginine (R), tyrosine (Y), isoleucine (I), and aspartate (D; Bogan and Thorn, 1998). Strikingly, with the exception of isoleucine, all of these residues are present in at least one of the three clusters, some appearing multiple times, while three of the four essential amino acids in the NTR are tryptophans or aspartates (Figures 2C and 5, B–F). Thus it is plausible that these regions could be involved in protein–protein interactions, possibly with a melanosomal factor promoting fibril aggregation or in self-interactions between NTRs (as proposed in the hypothetical model in Figure 9B) or between the PKD and the NTR. We also note that many of the amino acids in the three clusters, including all essential ones, are remarkably conserved; some, such as D73, P75, W153, Y159, W160, Q161, and V162, are completely conserved in many species ranging from humans to frogs, rodents, and fish (Figure 9A).

FIGURE 9:

(A) Evolutionary conservation of amino acid residues in clusters 1–3 (see Figure 2C for the definition and position of the three clusters). (B) Model of PMEL fibril formation. The NTR is required in cis to first drive the aggregation of the PKD-containing fibrillogenic fragment into an amyloid core matrix. MαC is then incorporated in a second step, promoting stability and the terminal proteolytic maturation of this fragment. Coaggregation of PKD and the RPT domain eventually leads to the formation of mature fibrils.

However, most NTR mutants presented in this study showed a phenotype distinct from the one observed with the deletion of the entire NTR. This phenotype, represented by prototype mutants NTR97 and NTR137 (Figure 3, B and F, and Supplemental Figures S1, A–C, and S2, A and C), included the production of only low levels of both fibrillogenic fragments (Figures 4, B and C, and 5, B and C, and Supplemental Figures S1, B and C, and S4, B and C), a subcellular distribution of the protein into a pattern more typical of lysosomes than melanosomes (see, e.g., G74A in Supplemental Figure S4F and Supplemental Figures S1D, S2A, phenotypes B and C, S3E, and S5C), and the deposition of fibrils in both morphologically normal organelles, as well as in abnormal organelles sharing lysosomal features (Figure 3F and Supplemental Figures S2B and S6A). Moreover, as discussed in Results, there is indirect evidence that these mutants form abnormal, SDS-insoluble aggregates in cells.

How can the formation of organelles that morphologically combine melanosomal features (high PMEL levels, visible fibrils) and lysosomal features (high LAMP1 levels, aggregate content) be explained? We speculate that at first the respective mutants migrate normally into melanosomes to initiate fibril formation. A fraction, however, may abnormally aggregate instead of incorporate into nascent fibrils, accumulate in this form, and gradually deteriorate melanosomal structure. Aggregate formation on the surface of ILVs, for instance, may interfere with the normal clearance of these bodies from the inner space of developing melanosomes (Hurbain et al., 2008), causing membranous deposits to accrue. Indeed, we frequently observe massive membrane accumulations in the respective organelles (Figure 3F, right, and Supplemental Figures S2B, right, and S6A, right, B). In this way, an increasingly lysosomal phenotype would be conferred onto organelles that were initially en route to developing into relatively normal melanosomes. The gradually advancing deterioration of melanosomal organelle identity may then lead to the acquisition of lysosomal markers, such as high levels of LAMP1. Finally, at some point the entire organelle may migrate into a more perinuclear position, where lysosomes typically reside (Supplemental Figure S2A, phenotype B; Leonhardt et al., 2010), thus resulting in the mixed subcellular distribution phenotype described in Supplemental Figure S2A.

Surprisingly, the NTR mutants that display a complete loss-of-function behavior do not show much of a trafficking or processing defect, with the exception that the terminal proteolytic maturation of MαC does not occur (Figures 6, F–H, and 7A). Instead, our results point to the NTR as a domain driving the proper aggregation of fibrillogenic fragments. Of interest, a recent study investigated the amyloidogenic potential of isolated PMEL domains expressed as recombinant protein in vitro and found that although the NTR and the PKD alone can form amyloid fibrils, the RPT domain cannot (Watt et al., 2009). At first glance, this appears to be at odds with what is observed in living cells, where the NTR is not or only to a minor extent associated with fibrils, whereas the RPT domain is a major component of these structures (Watt et al., 2009). However, the in vitro findings by Watt et al. (2009) fit remarkably well and appear complementary to our data obtained in melanoma cells in vivo, allowing us to interpret our data through the prism of this previous study and develop a hypothetical model of fibril formation (Figure 9B).

We propose that the NTR uses its amyloidogenic potential (or the potential to interact with itself in some other way or to interact with a fibril-promoting factor) to drive the assembly of the PKD-containing fibrillogenic fragment into a core matrix, a form in which this fragment accumulates to high cellular levels (Figure 8, B–F). This core matrix is likely to be the sheet-like aggregate structure shown to be formed in melanosomes of cells expressing ΔRPT (Figure 8, E and F). In contrast, in the absence of a functional NTR, as in D73K-expressing cells, the PKD-containing fibrillogenic fragment is still made (Figure 7A, leftmost), but it rapidly degrades. Our finding that the NTR needs to be linked to the PKD in cis in order to sustain its stable accumulation (Figure 8O), whereas this process is entirely independent of the RPT domain (Figure 8, B–F), suggests that it may occur after the separation of MαN from MαC but at a point where the NTR is still connected to the PKD via an intact protein backbone (Figure 9B). The function of the NTR, however, is probably limited to seeding the core matrix, because it is not or only to a minor extent present in the mature fibrils (Watt et al., 2009; Figures 1, A–D, and 9B). We propose that it is the establishment of the core matrix that eventually allows MαC to become incorporated into the growing amyloid, where it acquires stability (Figure 9B). This is consistent with the RPT domain being unable to form fibrils or even to accumulate by itself in the cell unless it receives assistance from other parts of the molecule (Figures 7A and 8, D, H, and O). Although this is still controversial (McGlinchey et al., 2009), it fits particularly well with the observation that the RPT domain has no or insufficient amyloidogenic potential on its own (Watt et al., 2009). However, since the ΔRPT mutant appears to form a morphologically abnormal and possibly more tightly packed amyloid (Figure 8E), the function of this domain is probably of regulatory nature, perhaps keeping the nascent aggregate from becoming toxic to melanocytes. Because we do not observe any mature RPT domain–containing fibrillogenic fragments in D73K-expressing cells, even in the presence of protease inhibitor (Figure 7A), we believe that the terminal proteolytic maturation of this fragment may only occur after embedding MαC into the core matrix (Figure 9B). This last step might serve to functionally and/or structurally modulate the nascent amyloid for tailoring it toward specific requirements related to melanin synthesis/deposition.

It is becoming increasingly clear that the formation of amyloid in vivo does often not only involve the aggregation of autonomous amyloidogenic units into stable fibrils, but that the process is limited, or modulated, or activated by regulatory domains or proteins (Landreh et al., 2012). This probably reflects the need to deal appropriately with potentially very dangerous molecules, whose premature runaway aggregation or aggregation in the wrong compartment would likely harm the cell severely. In line with the results by Watt et al. (2009), our data suggest that the major aggregating unit in PMEL is the PKD and that this domain is sandwiched between two regulatory modules. This arrangement would be quite similar to the situation in spidroins, the proteins forming the amyloid-like spider silk (Landreh et al., 2012). In spidroins the aggregating unit is flanked on either side by a regulatory domain. Both of these domains are involved in sensing the right time to activate the aggregation process, the C-terminal domain probably responding to mechanical stress, whereas the N-terminal domain responds to pH changes in the spinning duct (Landreh et al., 2012). In PMEL the one regulatory module is the NTR, which appears to be proamyloidogenic under the right circumstances, driving the downstream PKD into the core amyloid before it is proteolytically released. What exactly these right circumstances are is not clear, but a conformational change in response to dropping pH or exposure to a fibril-promoting factor in early-stage melanosomes may be attractive candidates. Flanking the PKD on the other side is the RPT domain, which we demonstrate is not necessary for the formation of an amyloid as such (Figure 8, E and F). However, the presence of the RPT domain seems to modify the fibril morphology (Figure 8E) and hence one might speculate, fibril function. Morphological similarities between the ΔRPT-derived amyloid and the very tightly packed fibrils formed by some pathogenic PMEL mutants (Watt et al., 2011) may suggest that one possible role of the RPT domain may be to modulate the PMEL amyloid in a way that possible toxicity is limited.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and cell culture

LG2-MEL-220 (Mel220), a human PMEL-deficient melanoma cell line (Vigneron et al., 2005), was grown in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)/10% fetal calf serum (FCS; HyClone, Logan, UT) containing nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), GlutaMax (Life Technologies), and penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies). Mel220 cells expressing wild-type or mutant PMEL (Pmel17-i; Theos et al., 2005) were grown in medium additionally containing 2 mg/ml G418 (Life Technologies). Mel220 cells expressing wild-type PMEL have been described previously (Leonhardt et al., 2010). Pepstatin A (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), E64-d (Biomol, Plymouth, PA), bestatin methylester (Calbiochem), and leupeptin (Sigma-Aldrich) were used at the concentrations indicated in Figure 7A.

Vector constructs and PMEL expression

PMEL in expression vector pBMN-IRES-neo (Leonhardt et al., 2010) served as template for a standard QuikChange mutagenesis using the primer pairs listed in Supplemental Table S2. All pBMN vectors containing mutant or wild-type PMEL were sequenced in both directions before retroviral transduction into Mel220 cells (Leonhardt et al., 2010). The pBMN derivative, 24 μg, and 24 μg of the retrovirus packaging vector pCL-Ampho were added to 3 ml Opti-MEM reduced serum medium (Life Technologies) and briefly vortexed. In parallel, 120 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added to 3 ml of Opti-MEM and also briefly vortexed. After a 5-min incubation at room temperature the two solutions were mixed, vortexed, and incubated for 20 min on a rotator at room temperature. Next 3 ml of the DNA–Lipofectamine mix was applied to each of two 10-cm Petri dishes containing a confluent layer of 293T cells that had been washed once with 8 ml of Opti-MEM. Additional Opti-MEM, 5 ml, was added to each plate. After a 4-h incubation at 37°C, all medium was removed, and 6 ml of prewarmed IMDM/10% FCS was added. 293T cells were then cultured overnight at 32°C, and the retrovirus-containing supernatant was harvested from both Petri dishes, centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min, and filtered through a 0.45-μm Millex-HA syringe filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Fresh 6 ml of IMDM/10% FCS was added to each of the two Petri dishes containing the 293T cells, and the cells were incubated again overnight at 32°C to produce more virus to be harvested the next day. To spinfect the melanoma cells, 6 ml of virus-containing supernatant containing 18 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 was applied to 500,000 Mel220 cells distributed in three wells of a six-well plate (2 ml of supernatant per 166,667 cells per well), and the cells were spun at 2500 rpm (1195 × g) and 32°C for 90 min. Subsequently, 2 ml of IMDM/10% FCS was added to each well, and cells were incubated overnight at 32°C. This spinfection protocol was repeated three times on three subsequent days. Mel220 transfectants expressing wild-type or mutant PMEL were then selected in medium containing 2 mg/ml G418 (Life Technologies), and expression of PMEL was assessed by Western blot.

Antibodies

Pep13h (Berson et al., 2001) and I51 (Watt et al., 2009; Leonhardt et al., 2010) are peptide antibodies recognizing the C-terminus of newly synthesized PMEL and the PKD, respectively. HMB50 (immunoglobulin G2a [IgG2a]), NKI-beteb (IgG2b; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), SPM142 (IgG1; Abcam), and HMB45 (IgG1; NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA) are mouse monoclonal antibodies recognizing the folded PKD in a conformation-sensitive manner (HMB50 and NKI-beteb; Harper et al., 2008; Leonhardt et al., 2010) or a sialylated epitope within the RPT domain (SPM142 and HMB45; Hoashi et al., 2006) of PMEL. The mouse monoclonal antibody 7E3 raised against full-length recombinant PMEL (ab117853; IgG2b) and the rabbit monoclonal antibody EP4863(2) (ab137078) raised against a peptide located within the first 100 amino acids of PMEL recognize the PMEL NTR (Figure 1, C–F) and were purchased from Abcam. The monoclonal antibodies 610823 (BD), H4A3 (IgG1) (Abcam), and ab70521 (Abcam) recognize the Golgi marker GM130, the lysosomal marker LAMP1, and the early endosomal marker EEA1, respectively. The goat polyclonal antibody ab52058 (Abcam) is specific for the C-terminus of PMEL. The horseradish peroxidase– or fluorophore-labeled, isotype-specific or conventional goat anti-mouse, goat anti-rabbit, and bovine anti-goat antibodies were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) or Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Detailed information about the reactivities in various applications of PMEL-specific antibodies used in this study is given in Supplemental Table S1 and the supplementary material of Leonhardt et al. (2010).

Immunofluorescence, flow cytometry, and Western blotting

Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as described (Leonhardt et al., 2007). Briefly, Mel220 transfectants were permeabilized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/0.5% bovine serum albumin/0.5% saponin and stained in a humidity chamber for 1 h with the indicated primary antibodies at concentrations recommended by the manufacturer or 1:25 for H4A3 (LAMP1), 1:10 for ab70521 (EEA1), 1:100 for Pep13h, 1:50 for HMB45, and 1:100 for HMB50. Alexa 647– or Alexa 488–conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) were used at a 1:100 dilution, and cells were mounted in ProLong Gold reagent (Invitrogen). Images were acquired using a Leica TCS SP2 laser-scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with an HCX PL APO 63× oil immersion objective at room temperature. The confocal microscope was controlled using Leica Confocal Software, version 2.61. Excitation of Alexa 488 was performed using a 488-nm argon laser, and excitation of Alexa 647 was performed using a 633-nm helium–neon laser.

Flow cytometry was performed as described (Leonhardt et al., 2005) using the antibody NKI-beteb at a concentration of 1:10 followed by Alexa 647–conjugated secondary antibodies on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer.

Total membrane fractions were prepared as in Leonhardt et al. (2010) and lysed in PBS/1% SDS/1% β-mercaptoethanol for 10 min at room temperature, followed by 10 min at 95°C, and subsequently analyzed by Western blotting. Western blotting was carried out as described (Rufer et al., 2007).

Electron microscopy

For conventional Epon embedding of cell samples, Mel220 transfectants were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde/2% sucrose in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4 (NaCaCo buffer), for 30 min at room temperature, followed by another 30 min in the same fixation solution at 4°C. Subsequently, cells were rinsed with NaCaCo buffer and further processed as described (Carrithers et al., 2009).

For cryo–immuno electron microscopy, samples were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde/0.1% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, followed by another 15 min in the same fixation solution at 4°C. Subsequently, cells were rinsed with PBS and further processed as described (Carrithers et al., 2009). For immunolabeling, cells were stained with the PMEL-specific antibodies HMB45 or HMB50 at 1:25, followed by protein A–gold (University of Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands) or gold anti-mouse conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), respectively.

Samples were viewed using a Tecnai BioTWIN transmission electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) at 80 kV. Images were collected using Morada CCD and iTEM software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Epon-embedded EM samples were first inspected to qualitatively determine whether the respective Mel220 transfectant formed conventional melanosomes, gave rise to abnormal fibril-containing organelles, or produced no fibrils at all. To quantify fibril formation, we then counted fibril-containing organelles in 15 arbitrarily chosen cells in one view field. We note that the presence of visible fibrils was the only criterion to count a respective compartment as “fibril containing” with no respect to whether the organelle had a conventional melanosomal or abnormal lysosomal morphology. Thus the numbers (mean) indicated in Figures 3, A–E, and 6, A–E, represent the total number of fibril-containing organelles (not the number of conventional melanosomes) per cell. Within those 15 cells, we also determined the percentage of abnormal fibril-containing organelles (abnormal organelles are more spherical than ellipsoid and contain extensive internal membranes, which are often multilamellar (see Figure 3F, 4 and 5, and Supplemental Figures S2B, 9–14, and S6A, panel B).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to M. Marks, A. Gown, and M. Skelly for their kind donation of the antibodies Pep13h and HMB50; X. Liu, R. Webb, and K. Zichichi at the Electron Microscopy Facility (Department of Cell Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT) for help with the EM analysis; and S. Mitchell and J. Cresswell for technical assistance. J. Grotzke, D. Sengupta, and M. Panter are acknowledged for critically reading the manuscript. This study was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Yale SPORE in Skin Cancer Grant 5P50 CA121974, and National Institutes of Health Grant R37-AI23081 (to P.C.), a Cancer Research Institute Fellowship (to R.M.L.), a Marie Curie Outgoing International Fellowship from the European Union and the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (Belgium; to N.V.), and a scholarship from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore (J.S.H.).

Abbreviations used:

- ADAM

a disintegrin and metalloprotease

- CTF

C-terminal fragment

- DAPT

N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester

- EEA1

early endosome antigen 1

- EM

electron microscopy

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- IF

immunofluorescence

- ILV

intralumenal vesicle

- LAMP

lysosomal-associated membrane protein

- MVE

multivesicular endosome

- NTR

N-terminal region

- PKD

polycystic kidney disease–like domain

- RPT

repeat domain

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E12-10-0742) on February 6, 2013.

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Berson JF, Harper DC, Tenza D, Raposo G, Marks MS. Pmel17 initiates premelanosome morphogenesis within multivesicular bodies. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3451–3464. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson JF, Theos AC, Harper DC, Tenza D, Raposo G, Marks MS. Proprotein convertase cleavage liberates a fibrillogenic fragment of a resident glycoprotein to initiate melanosome biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:521–533. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogan AA, Thorn KS. Anatomy of hot spots in protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 1998;280:1–9. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrithers MD, Chatterjee G, Carrithers LM, Offoha R, Iheagwara U, Rahner C, Graham M, Waxman SG. Regulation of podosome formation in macrophages by a splice variant of the sodium channel SCN8A. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8114–8126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801892200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimberu PM, Leonhardt RM. Cancer immunotherapy takes a multi-faceted approach to kick the immune system into gear. Yale J Biol Med. 2011;84:371–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler DM, Koulov AV, Alory-Jost C, Marks MS, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Functional amyloid formation within mammalian tissue. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper DC, Theos AC, Herman KE, Tenza D, Raposo G, Marks MS. Premelanosome amyloid-like fibrils are composed of only Golgi-processed forms of Pmel17 that have been proteolytically processed in endosomes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2307–2322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708007200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoashi T, Muller J, Vieira WD, Rouzaud F, Kikuchi K, Tamaki K, Hearing VJ. The repeat domain of the melanosomal matrix protein PMEL17/GP100 is required for the formation of organellar fibers. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21198–21208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoashi T, Tamaki K, Hearing VJ. The secreted form of a melanocyte membrane-bound glycoprotein (Pmel17/gp100) is released by ectodomain shedding. FASEB J. 2010;24:916–930. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-140921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurbain I, Geerts WJ, Boudier T, Marco S, Verkleij AJ, Marks MS, Raposo G. Electron tomography of early melanosomes: implications for melanogenesis and the generation of fibrillar amyloid sheets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19726–19731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803488105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer MP, Maruyama H, Huelsmann C, Baches S, Weggen S, Koo EH. Formation of Pmel17 amyloid is regulated by juxtamembrane metalloproteinase cleavage, and the resulting C-terminal fragment is a substrate for gamma-secretase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:2296–2306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808904200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landreh M, Johansson J, Rising A, Presto J, Jornvall H. Control of amyloid assembly by autoregulation. Biochem J. 2012;447:185–192. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt RM, Keusekotten K, Bekpen C, Knittler MR. Critical role for the tapasin-docking site of TAP2 in the functional integrity of the MHC class I-peptide-loading complex. J Immunol. 2005;175:5104–5114. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt RM, Lee SJ, Kavathas PB, Cresswell P. Severe tryptophan starvation blocks onset of conventional persistence and reduces reactivation of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5105–5117. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00668-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt RM, Vigneron N, Rahner C, Cresswell P. Proprotein convertases process Pmel17 during secretion. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9321–9337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.168088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt RM, Vigneron N, Rahner C, Van den Eynde BJ, Cresswell P. Endoplasmic reticulum export, subcellular distribution, and fibril formation by Pmel17 require an intact N-terminal domain junction. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16166–16183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.097725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlinchey RP, Shewmaker F, McPhie P, Monterroso B, Thurber K, Wickner RB. The repeat domain of the melanosome fibril protein Pmel17 forms the amyloid core promoting melanin synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13731–13736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906509106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Marks MS. Melanosomes—dark organelles enlighten endosomal membrane transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:786–797. doi: 10.1038/nrm2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Tenza D, Murphy DM, Berson JF, Marks MS. Distinct protein sorting and localization to premelanosomes, melanosomes, and lysosomes in pigmented melanocytic cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:809–824. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufer E, Leonhardt RM, Knittler MR. Molecular architecture of the TAP-associated MHC class I peptide-loading complex. J Immunol. 2007;179:5717–5727. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]