Abstract

Integrated reproductive health services for people living with HIV must address their fertility intentions. For HIV-serodiscordant couples who want to conceive, attempted conception confers a substantial risk of HIV transmission to the uninfected partner. Behavioral and pharmacologic strategies may reduce HIV transmission risk among HIV-serodiscordant couples who seek to conceive. In order to develop effective pharmaco-behavioral programs, it is important to understand and address the contexts surrounding reproductive decision-making; perceived periconception HIV transmission risk; and periconception risk behaviors. We present a conceptual framework to describe the dynamics involved in periconception HIV risk behaviors in a South African setting. We adapt the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skill Model of HIV Preventative Behavior to address the structural, individual and couple-level determinants of safer conception behavior. The framework is intended to identify factors that influence periconception HIV risk behavior among serodiscordant couples, and therefore to guide design and implementation of integrated and effective HIV, reproductive health and family planning services that support reproductive decision-making.

Keywords: conceptual framework, HIV, serodiscordant couples, pregnancy, safer conception

Many people living with HIV choose to have children1– 8 and require safer conception services to support their goals while minimizing the risk of HIV transmission to partner and child. Although the right to reproductive choice for people with HIV is protected under South African law, most South African (and global) HIV prevention and treatment programs focus on abstinence, condoms and pregnancy prevention as strategies to minimize HIV transmission.9 These approaches present HIV-serodiscordant couples who wish to conceive with the dilemma of putting the HIV-uninfected partner at risk of acquiring HIV or else setting aside desires for a child.3,4,6,10–13 For serodiscordant couples who desire and achieve pregnancy, the risk of HIV acquisition and transmission may increase during pregnancy.14–16 In addition, an acutely infected woman is more likely to transmit HIV to the child.17 Failure to communicate about and facilitate access to available risk reduction strategies for people living with HIV and their partners may contribute to new HIV infections among HIV-discordant couples and their children.18–20

Increasingly, calls have been made for the integration of reproductive health services for people living with HIV.21,22 Recent guidelines presented by the Southern African HIV Clinicians Society recommend that services should support people with HIV who choose to conceive.23 An expanding range of behavioral and pharmacological strategies may reduce HIV transmission risk for serodiscordant couples who wish to have a child.23–25 Behavioral strategies (home artificial insemination for couples where the woman is HIV-infected, unprotected sex limited to peak fertility),23,26 male circumcision for couples where the male partner is HIV-uninfected,27–29 antiretroviral therapy30 and pre-exposure antiretroviral prophylaxis26,31– 35 present options for HIV-discordant couples to minimize periconception HIV transmission risk and realize fertility goals.36 Periconception refers to the time period around attempted or actual conception. However, many clinicians do not, in the course of routine HIV-related clinical consultations, ask their clients about childbearing desires.8,9,18 Additionally, most HIV-affected couples neither share their plans for pregnancy with health care providers nor seek advice on how to have a safer pregnancy.5,18,37–41 HIV specialists, including program managers and health care professionals, need to acknowledge and support the fertility desires of serodiscordant couples. As men and women with HIV live longer, healthier lives, the significance of safer conception counseling for HIV-serodiscordant couples as a reproductive right is becoming more widely appreciated.42–44 For both rights-based and public health-based reasons, safer conception counseling should be included as a public health strategy to reduce HIV incidence among men, women and their children in settings with generalized HIV epidemics.45–47

Developing a conceptual framework for understanding periconception HIV risk among serodiscordant couples

Prior to rolling out safer conception intervention strategies, it is important to understand the context of reproductive decision-making, perceptions of HIV risk associated with conception (periconception risk), and periconception risk behavior among HIV-discordant couples. Informed by a recent qualitative study we conducted (summarized below and presented in full elsewhere),46 together with related literature as supporting evidence, we propose a conceptual framework highlighting key issues to consider in the provision of safer conception services to HIV-discordant couples. Our framework draws attention to some of the socially embedded and relationship-related complexities that may underpin safer conception intervention strategies and that, we argue, may fundamentally mediate the anticipated intervention trajectory in terms of safer conception outcomes.

Our recent qualitative study among men and women with HIV in Durban, South Africa explored the dynamics of reproductive decision-making, knowledge of horizontal transmission risk, and knowledge and use of safer conception strategies, as well as exposure to HIV risk while trying to become pregnant. The findings were based on semi-structured interviews with 30 women with HIV and 20 men with HIV. All study participants had HIV-negative sexual partners or partners of unknown status.46 All female study participants had experienced a pregnancy in the previous 12 months. Study participants voiced clear reasons for desiring children. They were rarely aware of safer conception strategies to reduce the risk of HIV transmission while trying to conceive, and engaged in unprotected sex in order to become pregnant. In addition, pregnancy planning occurred along a spectrum ranging from planned and wanted to unplanned and unwanted, with pregnancies very rarely being explicitly planned but often desired. Many female participants who reported an unintended pregnancy revealed strong male partner desire for that same pregnancy. Misconceptions about serodiscordance and fatalism regarding eventual seroconcordance (believing that both partners would eventually become HIV-positive) appeared to contribute to riskier behavior. While most study participants had not sought out clinical advice for safer conception, they expressed openness to receiving this. In summary, the study findings suggest that safer conception interventions are feasible; that such interventions should target both men and women; and that they should include serodiscordance counseling and promotion of contraception.46

Based on this study and a synthesis of the HIV-related literature on fertility desires, contraception and pregnancy, we developed a conceptual framework to describe the dynamics involved in conception-related HIV risk behaviors in a South African setting. While the conceptual framework was informed by research carried out in South Africa, the theoretical concepts and constructs supporting the framework apply to many settings where sexual transmission of HIV must be considered for safer conception. The framework identifies factors that influence periconception HIV risk behavior among serodiscordant couples in order to guide future design and implementation of integrated HIV, reproductive health and family planning services.

Overview

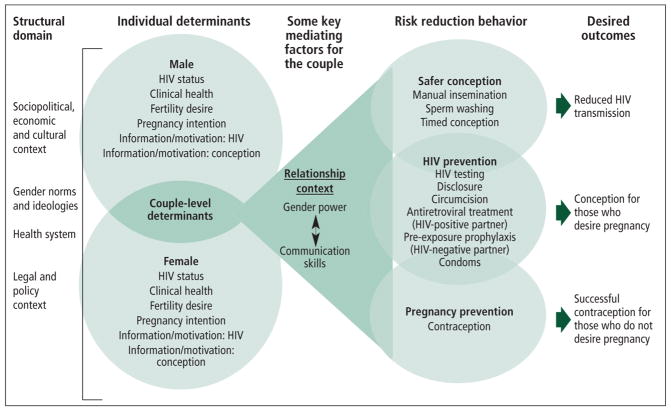

Our model (Figure 1) explores conception-related HIV risk behavior by building on recently proposed frameworks that integrate theory across individual, couples-based and structural levels.48,49 We draw on the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skill (IMB) Model of HIV Preventative Behavior as one component of the framework.50 After considering how the complexities of our primary study data could be represented by different theories and models of behavioral change (e.g. social cognitive theory, stages of change), the research team chose the IMB model as a base on which to develop a more comprehensive framework. The IMB model is useful, from an individual-level perspective, in guiding our understanding of HIV prevention behavior change. It incorporates terms that are familiar and easily interpretable, and has been widely utilized as a theoretical model for HIV prevention and reproductive health promotion.51,52 The IMB model, however, does not take into account all types of individual-level factors, nor does it acknowledge the role of structural and relationship factors. Our framework seeks to highlight multiple types of structural, individual and couples-based determinants of conception-related decision-making and risk behavior.40,41,45,46

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the processes involved in periconception decision-making and behavior among heterosexual HIV-serodiscordant couples

The conceptual framework consists of: (1) the overarching structural context, (2) individual-level male and female determinants, and (3) couple-level determinants out of which the relationship context arises, all of which impact (4) HIV and pregnancy risk reduction behaviors and ultimately (5) desired outcomes of safer conception interventions.

The structural domain

The structural domain, which frames and influences all aspects of the conceptual framework, consists of the overarching sociopolitical, economic and cultural context within which individuals are located. Economic and social constraints (e.g. poverty), and cultural and behavioral norms (e.g. hegemonic masculinities) form part of this context and influence HIV risk behavior (e.g. heightened risk through intimate partner violence).53–58 Gender ideologies including the enactment and perpetuation of norms surrounding manhood and womanhood are also located within the structural domain. Unequal employment opportunity in the context of pervasive poverty, as in South Africa, may enhance unequal power relations between men and women. Men may be afforded greater decision-making power, leaving women with little autonomy within relationships. Similarly, patriarchal-based societies, also part of the South African context, reinforce and regulate cultural expectations regarding how a “proper” woman should behave;59 this encompasses the regulation of family planning and childrearing. 60,61 Structural factors are important in that they provide a strong incentive or disincentive for people to act in a given way.62

Health systems, laws and policies are also key components of the structural context. For example, health systems may impact conception-related HIV transmission risk to couples through information or support given; provider attitudes towards clients expressing the desire to have a child; and availability of risk reduction services (e.g. instruction about limiting sex without condoms to peak fertility). Similarly, laws and policies may prevent individuals from accessing particular clinical services (e.g. early antiretroviral treatment for the infected partner). By incorporating the structural domain, our framework highlights that any safer conception intervention for serodiscordant couples must account for key structural factors in the setting in which it is to be implemented.

Individual determinants

The next domain of the proposed framework includes individual-level determinants, taking into account both partners. Individual factors such as overall health, HIV status and desire or intention to have a child affect reproductive and HIV risk behavior. For example, a person with HIV whose health improves as a result of taking antiretrovirals may want to have a child. Our proposed model identifies “fertility desire” and “pregnancy intention” as two distinct determinants: as defined here, fertility desire is the wish for a child in the undefined future, and pregnancy intention is the conscious intention to become pregnant, or impregnate a partner, in the near future. Information and motivation about HIV and conception also comprise an important subset of individual factors.63 For example, a man must know his HIV status (information), be sufficiently compelled to disclose to a partner (motivation) and be able to effectively communicate with his partner (behavioral skill) in order to engage in safer conception strategies with that partner. Similarly, for those who do not desire pregnancy, information about appropriate contraceptive strategies, motivation and the skills to consistently use them are all required to prevent unwanted pregnancies.

Individual-level information about HIV risk and conception is important. Many HIV-discordant couples do not understand the concept of serodiscordance. 46,64 Many individuals in our study assumed that their sexual partner(s) would necessarily share the same HIV status. Alternately, some HIV-positive individuals reported that when their partners tested HIV-negative, this was evidence of partners being innately protected against the virus.46 Both misconceptions may lead to riskier behaviors. Information that effectively explains serodiscordance may improve understanding of HIV transmission risk and motivate couples to protect themselves and/or others from potential risk.

Motivation and behavioral skills (the skill-set and perceived ability to effect a particular strategy) are critical components of managing HIV risk.65,66 One example of motivation that influences a person’s actions is perceived HIV risk to self, partner or fetus; another example of motivation is desire for a child. The relationship between pregnancy intention (motivation) and actual contraceptive use (behavior skill) is complex.61 For example, women who report not intending to become pregnant may do little or nothing to prevent pregnancy.67,68 Our study found that while very few pregnancies in the study population were planned, some unintended pregnancies were still desired.46 While this may relate to limited awareness of or ability to access contraception, it may also be due to the complex nature of pregnancy intention where pregnancies are desired, but not explicitly planned.69 Recognizing the different permutations of desire for a child and pregnancy intention (e.g. allowing for the reality that a woman may not plan to become pregnant in the immediate future but may also have a strong underlying desire to have a child with her partner) is essential for preventing HIV transmission and unintended pregnancy, as well as supporting healthy pregnancies.

An individual also requires specific skills, including self-efficacy, to carry out safer conception strategies.70,71 HIV disclosure to a partner is generally considered a key step for HIV prevention, but it requires effective communication skills.72–74 In addition, while antiretrovirals can reduce the risk of transmission to an HIV-uninfected partner, it is critical that the partner living with HIV adheres to the medications.30,75,76 For both those who desire children and those who do not, fertility desires, perceptions of fertility and prior experience with contraception will influence motivations and therefore behavior.

Couples-based context and key mediating factors

The framework draws particular attention to couple-level determinants. Couples-based dynamics occur at the intersection between the male and female spheres of the conceptual framework, out of which the relationship context arises. Conception and associated HIV transmission behaviors necessarily occur in a male-female pair. Some individuals do not wish to have a child or additional children. However, this individual-level decision may be challenged by a partner who desires a child and who influences reproductive decision-making. The key role of men in periconception decisions was highlighted in our study by the finding that an unintended pregnancy by the woman was often desired by the man.46 Other studies confirm the importance of men in reproductive desires and periconception behavior.3,4,9,13,67,77,78 Including men in discussions regarding contraception and safer sex practices at the health care facility and community level is vital for successful implementation of safer conception strategies specifically, as well as reproductive and sexual health more broadly.

Key mediating factors arising from the couples-based interaction occur within the realm of the relationship context, as indicated by the triangle in the conceptual framework. While the relationship context can include many elements, we highlight gender power dynamics and communication skills, which will likely have a powerful impact on conception and HIV transmission risk behaviors, regardless of individual-level capacities. For example, Mittal and colleagues found that relationship factors such as intimate partner violence directly affected sexual risk behavior independently of individual motivation and behavioral skills.66 In the case of HIV and gender-based violence, female-controlled contraception to prevent unwanted pregnancy and pre- and post-exposure antiretroviral prophylaxis to reduce the woman’s risk of HIV infection are priorities for HIV prevention and for reproductive, maternal and child health.

Communication skills may also determine how individual-level factors are mediated in the context of the relationship. Effective communication between couples is critical for interventions that affect sexual behavior to work (e.g. condom use, limiting unprotected sex to peak fertility in order to conceive).49,79 Crepaz and Marks found that among serodiscordant couples, those who disclosed and discussed the need for safer sex were more likely to practice safer sex than those who only disclosed.72 In our study population, there was very little reported communication between couples about sex.46 Couples counseling to improve communication and to educate men and women on detrimental gendered norms and behaviors is central to the success of any periconception risk reduction intervention.

Other social factors, external to feelings regarding the partnership, may affect the interplay between the individual and couple levels. For example, a woman may choose to maintain a current relationship despite the risk it poses to her if she perceives herself as entirely dependent on her partner. In her efforts to preserve this relationship, the woman may behave in ways that do not reflect her individual-level desires or intentions: she may consciously accede to her partner’s desire for a child in the interest of continuing the relationship even if she has no particular desire for a child herself.

Risk reduction behavior

Safer conception interventions include HIV prevention and pregnancy prevention as represented within the second set of circles in the conceptual framework.

HIV prevention, independent of pregnancy plans, includes condom use, medical male circumcision, antiretroviral therapy for the HIV-infected partner and pre-exposure prophylaxis for the HIV-uninfected partner. While some individuals and couples may rely on condoms for prevention of both HIV and pregnancy, it is essential that they use an additional effective contraceptive method if they wish to further reduce the risk of unintended pregnancy.80–85 There are several safe, reversible contraception options for women living with HIV, including intrauterine devices and barrier methods.23 Tubal ligation and vasectomy offer permanent contraception should this be desired. Combined oral contraceptives and injectable progestins are effective as pregnancy prevention although recent data suggest there may be an increased risk of HIV transmission with progesterone-only injectable hormonal contraceptives. 86 Given these findings and the fact that no contraceptive method is completely effective, couples should receive counseling on the need for concurrent use of condoms as an important HIV prevention and contraceptive strategy. In the event of an unintended and unwanted pregnancy, appropriate and context-specific support and interventions (including safe and legal pregnancy termination) should be available and accessible.

Safer conception and safer contraception should include as many HIV prevention strategies as possible. Safer conception strategies include manual insemination if the male partner is HIV-negative, 23 sperm washing if the male partner is HIV-positive87–89 and limiting unprotected sex to peak fertility to reduce HIV exposure (timed conception). 23 In addition, viral load suppression through antiretroviral therapy reduces horizontal and vertical HIV transmission risk,30,90–92 while local or systemic pre-exposure prophylaxis for the HIV-negative partner can confer additional protection.31–35 Prerequisites to accessing these strategies are HIV testing, linkage to care and, in most cases, HIV disclosure.

Desired outcomes

The final domain of the conceptual framework highlights the desired outcomes of the safer conception intervention, that is, reduced risk of HIV transmission, conception for those who desire it and successful contraception for those who do not desire a pregnancy. All preceding domains influence and impact behaviors that will ultimately determine these outcomes.

Using the conceptual framework to identify points of intervention

Integrated sexual and reproductive health programs for HIV-affected couples can address periconception risk through combination prevention approaches, including pharmacologic and behavioral strategies. The conceptual framework introduced here identifies structural-, individual- and couple-level factors to consider in the development of periconception risk reduction interventions. Since structural-level factors can fundamentally impact the feasibility of risk-reduction strategies, they must be carefully considered when designing safer conception interventions. Although change in the structural domain may be difficult for health practitioners to effect, some of the other factors identified here may be addressed directly in periconception risk reduction interventions. We draw particular attention to the couple level, where effective communication skills and awareness of gendered norms within relationships may influence many individual-level determinants, for example, sexual coercion. Periconception risk reduction interventions need to account for mediating factors occurring within the relationship context since these factors may ultimately influence vulnerability to HIV despite individual-level capacity.

There is some indication that men and women may be more willing to engage in HIV risk reduction in the context of protecting a future child.46,93 The wellbeing of future or actual children offers a potential strategy to open risk-reduction communication between couples.93 While the willingness to communicate about safer sex in these instances may, in reality, only be temporary, it is a key entry point for HIV risk reduction strategies, particularly in the context of unequal power relationships.

Interventions that include antiretrovirals will necessarily involve health care workers. By better understanding the complex processes underlying periconception risk behavior, as proposed by the conceptual framework, health care workers may optimize their supportive role by helping to limit their clients’ exposure to HIV risk through the provision of information and through couples-based counseling that addresses disclosure, serodiscordance and risk reduction strategies. They may also affect individuals’ actions by encouraging adherence to risk reduction strategies.

Health care workers may experience ethical conflicts in providing safer conception services, especially in settings with high rates of poverty and intimate partner violence.53,84 For instance, a male partner may seek safer conception services for himself and his partner, but on individual consultation the female partner may indicate that she does not desire a child, and insists that this cannot be communicated to her partner. Health care providers may also face situations where a person living with HIV wishes to access safer conception services but has not yet disclosed his/her HIV status to the partner. Drawing attention to ethical sensitivities that may arise in providing safer conception interventions should be a part of reproductive counseling training for health care providers.

Conclusion

While there is increasing consensus regarding the need for safer conception services for HIV-affected couples, service provision is conceptually, ethically and technically complex. The reality is that HIV-affected couples are likely to fulfill their fertility desires even when aware of the risks involved and in the absence of periconception support services. Providing these services offers opportunities not only to reduce HIV transmission to partners and children, and to support pregnancy intentions, but also to begin to address long-term relationship dynamics which contribute to gendered vulnerabilities and high-risk HIV transmission behaviors.

The conceptual framework presented in this article is intended for testing, refinement and further development. In its current form, it offers insight into some complexities that researchers, policy makers and health care workers should consider when developing and delivering interventions for serodiscordant couples who wish to conceive. While the conceptual framework was informed by research carried out in South Africa, as noted earlier, the theoretical concepts and constructs supporting the framework may apply to many settings. Given the success of couples-based interventions, 94–96 it is suggested that at a minimum couples-based counseling be incorporated routinely into safer conception services.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Matthews received funding support from the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Postdoctoral Fellowship in Tropical Infectious Diseases, the Mark and Lisa Schwartz Family Foundation and a K23 award (NIMH MH095655).

Dr. Bangsberg was supported by the Mark and Lisa Schwartz Family Foundation and by a K24 award (NIMH MH087227).

References

- 1.Kakaire O, Osinde M, Kaye D. Factors that predict fertility desires for people living with HIV infection at a support and treatment centre in Kabale, Uganda. Reproductive Health. 2010;11(7):27. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peltzer K, Chao L, Dana P. Family planning among HIV positive and negative prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) clients in a resource poor setting in South Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(5):973–79. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9365-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakayiwa S, Abang B, Packel L, et al. Desire for children and pregnancy risk behavior among HIV-infected men and women in Uganda. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(Suppl 4):S95–S104. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyeza-Kashesya J, Ekstrom A, Kaharuza F, et al. My partner wants a child: a cross-sectional study of the determinants of the desire for children among mutually disclosed sero-discordant couples receiving care in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:247. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaida A, Laher F, Strathdee SA, et al. Childbearing intentions of HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Soweto, South Africa: the influence of expanding access to HAART in an HIV hyper-endemic setting. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(2):350–58. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.177469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myer L, Morroni C, Rebe K. Prevalence and determinants of fertility intentions of HIV-infected women and men receiving antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2007;21(4):278–85. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nattabi B, Li J, Thompson S, et al. A systematic review of factors influencing fertility desires and intentions among people living with HIV/AIDS: implications for policy and service delivery. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(5):949–68. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9537-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz S, Mehta S, Taha T, et al. High pregnancy intentions and missed opportunities for patient-provider communication about fertility in a South African cohort of HIV-positive women on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS and Behavior. 2012 Jan;16(1):69–78. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9981-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper D, Harries J, Myer L, et al. “Life is still going on”: reproductive intentions among HIV-positive women and men in South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 2007;65:274–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panozzo L, Battegay M, Friedl A, et al. High risk behaviour and fertility desires among heterosexual HIV-positive patients with a serodiscordant partner–two challenging issues. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2003;133(7–8):124–27. doi: 10.4414/smw.2003.10124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brubaker S, Bukusi E, Odoyo J, et al. Pregnancy and HIV transmission among HIV-discordant couples in a clinical trial in Kisumu, Kenya. HIV Medicine. 2011;12(5):316–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maier M, Andia I, Emenyonu N, et al. Antiretroviral therapy is associated with increased fertility desire, but not pregnancy or live birth, among HIV-positive women in an early HIV treatment program in rural Uganda. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(Suppl 1):28–37. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9371-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ujiji OA, Ekström A, Ilako F, et al. I will not let my HIV status stand in the way. Decisions on motherhood among women on ART in a slum in Kenya - a qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health. 2010;28(10):13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wand H, Ramjee G. Combined impact of sexual risk behaviors for HIV seroconversion among women in Durban, South Africa: implications for prevention policy and planning. AIDS and Behavior. 2011 Feb;15(2):479–86. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9845-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mugo NR, Heffron R, Donnell D, et al. Increased risk of HIV-1 transmission in pregnancy: a prospective study among African HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. AIDS. 2011;25(15):1887–95. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834a9338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moodley D, Esterhuizen TM, Pather T, et al. High HIV incidence during pregnancy: compelling reason for repeat HIV testing. AIDS. 2009;23:1255–59. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832a5934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moodley D, Esterhuizen T, Reddy L, et al. Incident HIV infection in pregnant and lactating women and its effect on mother-to-child transmission in South Africa. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2011;203(9):1231–34. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper D, Moodley J, Zweigenthal V, et al. Fertility intentions and reproductive health care needs of people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for integrating reproductive health and HIV care services. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(Suppl 1):38–46. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guthrie BL, de Bruyn G, Farquar C. HIV-1-discordant couples in Sub-Saharan Africa: explanations and implications for high rates of discordancy. Current HIV Research. 2007;5:416–29. doi: 10.2174/157016207781023992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunkle K, Stephenson R, Karita E, et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: an analysis of survey and clinical data. Lancet. 2008;371(9631):2183–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60953-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Global Health Initiative. [Accessed 26 May 2012.];Implementation of the global health initiative: strategy document. 2010. 2010 At: http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/136504.pdf.

- 22.WHO UNFPA, IPPF, UNAIDS. Sexual and reproductive health and HIV/AIDS: a framework for priority linkages. 2011. At: http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/stis/framework.html.

- 23.Bekker L, Black V, Myer L, et al. Guideline on safer conception in fertile HIV-infected individuals and couples. The South African Journal of HIV Medicine. 2011 Jun;:31–44. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthews LT, Mukherjee JS. Strategies for harm reduction among HIV-affected couples who want to conceive. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(Suppl 1):5–11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthews LT, Baeten JM, Celum C, et al. Periconception pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV transmission: benefits, risks, and challenges to implementation. AIDS. 2010 Aug 24;24(13):1975–82. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833bedeb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vernazza P, Graf I, Sonnenberg-Schwan U, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis and timed intercourse for HIV-discordant couples willing to conceive a child. AIDS. 2011 Oct 23;25(16):2005–08. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834a36d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, et al. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Medicine. 2004;2:e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey R, Moses S, Parker C, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:643–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray R, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369:657–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen M, Chen Y, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 Aug 11;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012 Aug 2;367(5):411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim S, Frohlich J, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329(5996):1168–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grant R, Lama J, Anderson P, et al. Pre-exposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(27):2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baeten JM, Donnell D, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012 Aug 2;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012 Aug 2;367(5):423–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. Couples HIV testing and counselling and antiretroviral therapy for treatment and prevention in serodiscordant couples. Geneva: 2011. [Date accessed: 21 June 2012]. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2012/9789241501972_eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaida A, Laher F, Strathdee S, et al. Contraceptive use and method preference among women in Soweto, South Africa: the influence of expanding access to HIV care and treatment services. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e13868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finocchario-Kessler S, Dariotis JK, Sweat MD, et al. Do HIV-infected women want to discuss reproductive plans with providers, and are those conversations occurring? AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2010;24(5):317–23. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orner P, Cooper D, Myer L, et al. Clients’ perspectives on HIV/AIDS care and treatment and reproductive health services in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2008;20(10):1217–23. doi: 10.1080/09540120701867008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCarraher D, Cuthbertson C, Kung’u D, et al. Sexual behavior, fertility desires and unmet need for family planning among home-based care clients and caregivers in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2008;20(9):1057–65. doi: 10.1080/09540120701808812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthews LT, Crankshaw TL, Giddy J, et al. Reproductive counseling by clinic healthcare workers in Durban, South Africa: perspectives from HIV-positive men and women reporting serodiscordant partners. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/146348. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.London L, Orner J, Myer L. “Even if you’re positive, you still have rights because you are a person”: human rights and the reproductive choice of HIV-positive persons. Dev World Bioeth. 2008;8(1):11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mantell JE, Smit JA, Stein ZA. The right to choose parenthood among HIV-infected men and women. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2009;30(4):367–78. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2009.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gruskin S, Ferguson L, O’Malley J. Ensuring sexual and reproductive health for people living with HIV: an overview of key human rights, policy and health systems issues. Reproductive Health Matters. 2007;15(29 Suppl):4–26. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)29028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health Organization. Guidance on couples HIV testing and counselling including antiretroviral therapy for treatment and prevention in serodiscordant couples. Geneva: 2012. [Accessed on 25 June 2012]. At: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/9789241501972/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matthews L, Crankshaw T, Giddy J, et al. Reproductive decision-making and periconception practices among HIV-positive men and women attending HIV services in Durban, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 2011 Oct 29; doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0068-y. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.GNP+ ICW Young Positives et al. Advancing the sexual and reproductive health and human rights of people living with HIV: A guidance package. Amsterdam: The Global Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albarracin D, Rothman AJ, Di Clemente R, et al. Wanted: a theoretical roadmap to research and practice across individual, interpersonal, and structural levels of analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2010 Dec;14(Suppl 2):185–88. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9805-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karney BR, Hops H, Redding CA, et al. A framework for incorporating dyads in models of HIV-prevention. AIDS and Behavior. 2010 Dec;14(Suppl 2):189–203. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9802-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fisher J, Fisher W. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:455–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Byrne D, Kelley K, Fisher WA. Unwanted teenage pregnancies: incidence, interpretation, and intervention. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 1993;2(2):101–13. doi: 10.1016/s0962-1849(05)80116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fisher WA, Fisher JD. Understanding and promoting sexual and reproductive health behavior. In: Rosen R, Davis C, Ruppel H, editors. Annual Review of Sex Research. Mason City, IA: Society for the Scientific Study of Sex; 1999. pp. 39–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, et al. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. The Lancet. 2004 May 1;363(9419):1415–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koenig LJ, Moore J. Women, violence, and HIV: a critical evaluation with implications for HIV services. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2000;4(2):103–09. doi: 10.1023/a:1009570204401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maharaj P, Munthree C. Coerced first sexual intercourse and selected reproductive health outcomes among young women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2007;39(2):231–44. doi: 10.1017/S0021932006001325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morrill AC, Noland C. Interpersonal issues surrounding HIV counseling and testing, and the phenomenon of “testing by proxy. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(2):183–98. doi: 10.1080/10810730500526745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strebel A, Lindegger G. Power and responsibility: shifting discourses of gender and HIV/AIDS. Psychology in Society. 1998;24:4–20. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jewkes R, Abrahams N. The epidemiology of rape and sexual coercion in South Africa: An overview. Social Science and Medicine. 2002 Oct;55(7):1231–44. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. Lancet. 2002;359:1423–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.MacPhail C, Pettifor AE, Pascoe S, et al. Contraception use and pregnancy among 15–24 year old South African women: a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. BMC Medicine. 2007;5(31) doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Todd CS, Stibich MA, Laher F, et al. Influence of culture on contraceptive utilization among HIV-positive women in Brazil, Kenya, and South Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 2011 Feb;15(2):454–68. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9848-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Latkin C, Weeks MR, Glasman L, et al. A dynamic social systems model for considering structural factors in HIV prevention and detection. AIDS and Behavior. 2010 Dec;14(Suppl 2):222–38. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9804-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fisher J, Fisher W, Shuper P. The information-motivation-behavioral skill model of HIV preventive behavior. In: DiClemente R, Crosby R, Kegler M, editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass Publishers; 2009. pp. 22–63. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bunnell R, Nassozi J, Marum E, et al. Living with discordance: knowledge, challenges, and prevention strategies of HIV-discordant couples in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2005;17:999–1012. doi: 10.1080/09540120500100718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalichman S, Stein J, Malow R, et al. Predicting protected sexual behavior using information-motivation-behavioral skills model among adolescent substance abusers in court-ordered setting. Psychology, Health and Medicine. 2002;7(3):327–38. doi: 10.1080/13548500220139368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mittal M, Senn T, Carey M. Intimate partner violence and condom use among women: does the information-motivation-behavioral skills model explain sexual risk behavior? AIDS and Behavior. 2012 May;16(4):1011–19. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9949-3. (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laher F, Todd CS, Stibich MA, et al. A qualitative assessment of decisions affecting contraceptive utilization and fertility intentions among HIV-positive women in Soweto, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:S47–S54. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9544-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harrison A, O’Sullivan LF. In the absence of marriage: long-term concurrent partnerships, pregnancy, and HIV risk dynamics among South African young adults. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(5):991–1000. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9687-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McQuillan J, Greil AL, Shreffler KM. Pregnancy intentions among women who do not try: focusing on women who are okay either way. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011;15(2):178–87. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0604-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bandura A. Perceived self-efficacy in the exercise of control over AIDS infection. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1990;13(1):9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Crepaz N, Marks G. Serostatus disclosure, sexual communication and safer sex in HIV-positive men. AIDS Care. 2003;15(3):379–87. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000105432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Black BP, Miles MS. Calculating the risks and benefits of disclosure in African American women who have HIV. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2002;31:668–97. doi: 10.1177/0884217502239211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Arnold EM, Rice E, Flannery D, et al. HIV disclosure among adults living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2008;20:80–92. doi: 10.1080/09540120701449138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mills E, Nachega J, Bangsberg D, et al. Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Medicine. 2006;3:e438, 1637123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mills E, Nachega J, Buchan I, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006 Aug 9;296(6):679–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.679. (2006a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yeatman S. HIV infection and fertility preferences in rural Malawi. Studies in Family Planning. 2009;40(4):261–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2009.00210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Smith D, Mbakwem B. Life projects and therapeutic itineraries: marriage, fertility, and antiretroviral therapy in Nigeria. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 5):S37–S41. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000298101.56614.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles C, et al. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. AIDS. 2008;22(10):1177–94. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ff624e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Myer L, Mlobeli R, Cooper D, et al. Knowledge and use of emergency contraception among women in the Western Cape province of South Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health. 2007 Sep 12;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rochat TJ, Richter LM, Doll HA, et al. Depression amongst pregnant rural South African women undergoing HIV testing. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295(12):1376–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pettifor A, Rees H, Steffenson A, et al. HIV and sexual behaviour among young South Africans: national survey of 15–24 year olds. Johannesburg: Reproductive Health Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kunene B, Beksinska M, Zondi S, et al. Involving men in maternity care, South Africa. Durban: Reproductive Health Research Unit, University of Witwatersrand; 2004. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, et al. Prevalence and patterns of gender-based violence and revictimization among women attending antenatal clinics in Soweto, South Africa. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004 Aug 1;160(3):230–39. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hubacher D, Mavranezouli I, McGinn E. Unintended pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: magnitude of the problem and potential role of contraceptive implants to alleviate it. Contraception. 2008;78(1):73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Heffron R, Donnell D, Rees H, et al. Use of hormonal contraceptives and risk of HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2012;12(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70247-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Semprini A, Fiore S, Pardi G. Reproductive counselling for HIV-discordant couples. Lancet. 1997;349:1401–02. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bujan L, Hollander L, Coudert M, et al. Safety and efficacy of sperm washing in HIV-1-serodiscordant couples where the male is infected: results from the European CREAThE network. AIDS. 2007;21:1909–14. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282703879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vitorino R, Grinsztejn B, de Andrade C, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness and safety of assisted reproduction techniques in couples serodiscordant for human immunodeficiency virus where the man is positive. Fertility and Sterility. 2011;95(5):1684–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Quinn T, Wawer M, Sewankambo N, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:921–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Attia S, Egger M, Muller M, et al. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23:397–404. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b7dca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Donnell D, Baeten J, Kiarie J, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2092–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mindry D, Maman S, Chirowodza A, et al. Looking to the future: South African men and women negotiating HIV risk and relationship intimacy. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011;13(5):589–602. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.560965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Allen S, Meinzen-Derr J, Kautzman M, et al. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS. 2003;17(5):733–40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303280-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.El-Bassel N, Jemmott JB, Landis JR, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Multisite Eban HIV/STD prevention intervention for African American HIV serodiscordant couples: a cluster randomized trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170(17):1594–01. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Burton J, Darbes LA, Operario D. Couples-focused behavioral interventions for prevention of HIV: systematic review of the state of evidence. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9471-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]