Abstract

Male animals often change their behavior in response to the level of competition for mates. Male Lincoln's sparrows (Melospiza lincolnii) modulate their competitive singing over the period of a week as a function of the level of challenge associated with competitors' songs. Differences in song challenge and associated shifts in competitive state should be accompanied by neural changes, potentially in regions that regulate perception and song production. The monoamines mediate neural plasticity in response to environmental cues to achieve shifts in behavioral state. Therefore, using high pressure liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection, we compared levels of monoamines and their metabolites from male Lincoln's sparrows exposed to songs categorized as more or less challenging. We compared levels of norepinephrine and its principal metabolite in two perceptual regions of the auditory telencephalon, the caudomedial nidopallium and the caudomedial mesopallium (CMM), because this chemical is implicated in modulating auditory sensitivity to song. We also measured the levels of dopamine and its principal metabolite in two song control nuclei, area X and the robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA), because dopamine is implicated in regulating song output. We measured the levels of serotonin and its principal metabolite in all four brain regions because this monoamine is implicated in perception and behavioral output and is found throughout the avian forebrain. After controlling for recent singing, we found that males exposed to more challenging song had higher levels of norepinephrine metabolite in the CMM and lower levels of serotonin in the RA. Collectively, these findings are consistent with norepinephrine in perceptual brain regions and serotonin in song control regions contributing to neuroplasticity that underlies socially-induced changes in behavioral state.

Introduction

Animals must adjust their behavior according to changing and unpredictable environmental conditions, including variable social conditions. The monoamine neuromodulators play a pivotal role in mediating responses to changing conditions by modifying neural processes underlying behavioral plasticity [1]–[6]. Specifically, monoamines can modify neural selectivity and the efficiency of synaptic transmission to achieve shifts in behavioral state such as arousal, attention, motivation and mood [2], [4], [7], [8]. Though the monoamines have overlapping roles in regulating neuroplasticity, each monoamine is implicated principally in particular cognitive processes essential to adaptive changes in behavior. Norepinephrine is particularly involved in the regulation of attention and sensory processing central to memory consolidation and the optimization of behavior [4], [7]; dopamine is especially involved in motor control as well as reinforcement, reward anticipation and goal-directed behaviors [9]–[11]; and serotonin has been implicated in regulating diverse behaviors including memory formation and maintenance, sensory encoding, sensory-motor learning [12]–[14], sexual behavior and aggression [1], [3], [15].

Understanding the coordinated roles of the monoamines in regulating adaptive shifts in social behavior requires presenting animals with a social context that elicits a change in behavioral state, but one which falls within the scope of naturally occurring behaviors. We previously demonstrated that simulating shifts in the competitiveness of the social environment, using playback of naturally variable songs, induced changes in the competitive behavioral state of territorial male Lincoln's sparrows (Melospiza lincolnii; [16]; Fig. 1). This research system provides an opportunity to examine the relationship between monoamine levels and socially-induced modulation of behavioral state. Here, using the same wild-caught male Lincoln's sparrows from the above-mentioned study, we examined the effect of natural variation in the competitiveness of the song environment on forebrain monoamine levels.

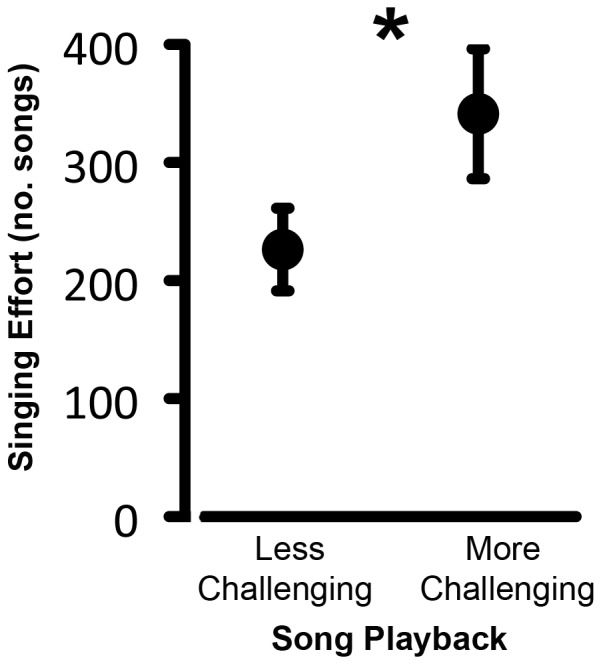

Figure 1. Effect of Prior Song Challenge on Singing Effort.

The mean (± standard errors) number of songs males in the more challenging and less challenging treatment group produced the morning after the song playback ceased. The difference in song number reflects differences in males' competitive state because singing was not occurring in response to a playback stimulus. Figure modified from Sewall et al. (2010) with permission.

Male animals often must compete with one another for access to mates, and success in such male-male competition directly influences males' fitness. The level of challenge during mating and territorial contests changes, though, and in many songbirds variation in male-male competition is reflected by singing behavior [17], [18]. Several song features are reliably associated with measures of male condition [19]–[25], permitting prospective mates and competitors to evaluate individuals based on their songs [18], [26]–[28]. For example, songs that are longer or more complex can be associated with higher-quality and thus more challenging competitors [19], [22], [23], [25]. When territorial male songbirds are presented with songs associated with greater challenge in brief playback experiments, they respond more aggressively, which includes increasing the number of songs they produce [29]–[32].

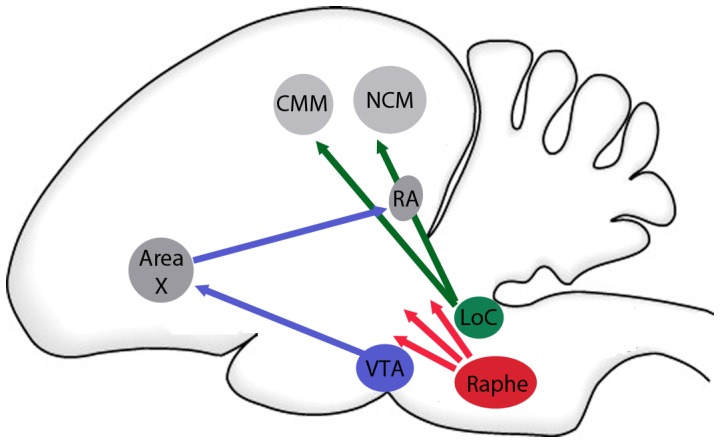

Similarly, male Lincoln's sparrows exposed to persistent playback of more challenging songs (songs that are longer and more complex than average for the population, see methods) for a week increase the number of songs they produce (i.e., their competitive effort) more than males exposed to less challenging (shorter and less complex than average) songs ([16]; Fig. 1). The effects of exposure to songs of varying level of challenge persist after playbacks have ended, indicating that these behavioral differences reflect changes in the males' competitive states [16], [33], [34]. Given that socially-elicited changes in behavioral state can be mediated by monoamine-dependent neural plasticity, we examined the relationship between social challenge and the levels of particular monoamines in two forebrain networks implicated in song perception and the modulation of song motor output (Fig. 2). Because norepinephrine is hypothesized to modify the sensitivity of neurons in the avian auditory forebrain [5], [35]–[39], and because the auditory forebrain receives strong noradrenergic innervation [40], we quantified the levels of norepinephrine and it's primary metabolite in two areas that mediate the perception of conspecific songs, the caudal medial nidopallium (NCM) and the caudal medial mesopallium (CMM; [41]–[46]; Fig. 2). Similarly, because dopamine is implicated in regulating context-specific singing through action in nodes of the song control system [11], [47], [48], and because these brain regions receive particularly strong innervation from a dopaminergic center (the ventral tegmental area; [49]–[54]; Fig. 2), we measured the levels of dopamine and its primary metabolite in two nuclei of the song control pathway specifically implicated in context-dependent singing, area X and the robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA; [55], [56]). We measured the levels of serotonin and its primary metabolite in all four brain regions of interest, because much of the avian forebrain receives strong serotonergic innervation from the raphe nuclei ([57]; Fig. 2) and serotonin is implicated in the regulation of perception [3], [58]–[61], as well as in regulating sensory-motor behaviors including vocalizing [62]–[64], and aggression [1], [15], [65], which could include singing. Finally, we examined the relationship between the monoamines, the song playback treatment, and recent song output to determine if monoaminergic activity was explained by recent motor output, in addition to the level of song challenge. The primary goal of this study is to identify the monoamine changes across integrated brain regions, which may underlie socially-induced shifts in behavior. This work could lay the groundwork for future comparisons of monoamine expression in wild populations. Additionally, the approach of describing concerted monoaminergic changes across brain regions emphasizes the importance of examining integrated changes throughout the brain and generates hypotheses about monoaminergic function under naturalistic conditions, which may serve as the basis for future manipulations of these brain substrates.

Figure 2. Auditory, Song Control and Monoamine Centers of the Avian Brain.

A diagram of the auditory processing, song production and monoamine centers of the brain examined in this study. Though dopaminergic, noradrenergic and serotonergic cells are found in all of the brain regions of interest, the figure illustrates our approach of focusing on a subset of monoaminergic correlates of behavior. Green: noradrenergic projections, blue: dopaminergic projections, red: serotonergic projections.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The U.S. Department of the Interior's Fish and Wildlife Service (permit MB099926), the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Forest Service (authorization COL258), the State of Colorado's Department of Natural Resources Division of Wildlife (license 06TR1056A2), the Town of Silverton, Colorado, USA, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 05-138.0-A) each granted permission to conduct the procedures described in this study.

Experimental procedures and subjects

We presented adult male Lincoln's sparrows with unique sets of either more challenging or less challenging songs (see song playback treatment), played back repeatedly for 7 consecutive days, to elicit a change in competitive behavior. On the 8th morning, after playback ceased, we collected the males' brains and used HPLC to measure levels of key monoamines and their primary metabolites from tissue samples from auditory processing and song control brain regions. Specifically, on 12 May 2008, close to the start of the breeding season for this species, we initiated the study by moving 18 male Lincoln's sparrows between the ages of 1–2 years from outdoor aviaries at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to indoor cages. We had captured these males in the wild at approximately 8 days of age, hand-fed them, and tutored them as a single group using recorded song and live adult males. For the entire study we provided the birds with ad libitum food (Daily Maintenance; Roudybush, Woodland, CA, USA) and water. Once in individual cages, we held the subjects on a 16 hour light and 8 hour dark photoperiod (lights on at 05:00 and off at 21:00 EDT) for 2 weeks to maintain their reproductive-like physiological state [66]. Because we had only eight experimental set-ups, we designed the study as two balanced replicates, which occurred over two consecutive weeks. At 09:00 on 26 May 2008, we randomly assigned and transferred each of the first 8 subjects to eight individual cages within each of eight sound attenuation chambers (58×41×36 cm, Industrial Acoustics Company, New York, NY, USA). Each chamber had a fan-driven ventilation system and a light that we used to maintain the above light-dark schedule. We equipped each chamber with (1) an omni-directional microphone (Senheiser ME 62, Old Lyme, CT, USA) plugged into an eight-line recording interface (PreSonus FP10, Baton Rouge, LA, USA) and a computer running Sound Analysis Pro II software (SAP Version 2.062; [67]) and (2) a speaker (Pioneer TS-G1041R, Tokyo, Japan) plugged into an individual amplifier (Audiosource Amp 5.1A, Portland, OR, USA) attached to an eight-channel interface (M-Audio Delta1010, Irwindale, CA, USA) and a computer running Pro Tools M-Powered playback software (version 7.1, M-Audio, Irwindale, CA, USA). We permitted the males to acclimate to the chambers until 06:00 the next day, when we began to play each male songs from one of two treatments – either songs that were less challenging or more challenging (see song playback treatments, below). We assigned males to chambers such that subjects of each treatment were spatially interspersed throughout the room. We exposed the males to these song treatments and collected audio recordings from these subject males for 7 days. On the eighth day we provided no playback but continued collecting audio recordings of the subjects until 09:00, when we began rapidly decapitating and removing the brain of each male. All brain removal was complete by 10:30.

Using previously described protocols [33], we fixed one hemisphere (alternating left and right between subjects within each treatment group) in 5% acrolein, saturated it with 30% sucrose for cryoprotection, froze it on dry ice and held it at −80°C for approximately two weeks until Nissl staining was conducted. The second hemisphere was fresh frozen on dry ice and held at −80°C until brain regions were micropunched and HPLC was conducted (ca. 18 wks, see below). We repeated these procedures with the second session of 8 males, beginning on 4 June 2008. During this second session, one male from each treatment group was found dead on the second day of playbacks. Two new males were added to the study beginning 6 June 2008, resulting in a third session that consisted of only two subjects, one from each treatment group, and ended 2 days after the second session.

Song playback treatments

For the song playbacks, we used two sets of 48 recordings each (96 songs in total) from a library of songs collected from the subjects' natal meadow. We initially categorized each of the recorded songs used in this study as being either higher-quality (longer in duration and more complex based on their containing more syllables and more phrases), or lower-quality (shorter in duration and less complex, containing fewer syllables and fewer phrases), than average for the population [16]. This categorization is biologically relevant as, in an earlier experiment, female Lincoln's sparrows showed greater behavioral activity in response to playback of the set of songs we had categorized as higher-quality, compared to the set of lower-quality songs [68]. Given that males use song to attract and compete for females, songs preferred by females are presumably more challenging to male competitors. In the present experiment we refer to the set of higher-quality songs that females were more responsive to as more challenging songs and the set of lower-quality songs as less challenging songs to emphasize that the signaler and receiver are both males and that song playback reflects a social challenge. We chose to expose males to these two song playback treatments because we are interested in how natural variation in song challenge is transduced into behavioral and brain responses. We did not include a “no-song” or "heterospecific-only-song" treatment group because isolation from conspecific song is not a natural condition for Lincoln's sparrows in this reproductive state and would be expected to elicit abnormal behavioral and brain responses that would be inappropriate to assume as base-line values.

We exposed each male subject to either six unique songs from the more challenging stimulus set or six unique songs from the less challenging stimulus set. We used six songs per male to mimic different competitive environments, as may occur on a breeding meadow for this species, rather than challenge from a single competitor. The songs we played each subject were produced by at least two free-living males, neither of which provided recordings for the tutoring phase mentioned above. To maximize the generalizability of our study [69], [70] we used the playback recordings from each free-living male for no more than one subject in each of the two treatment groups. In some cases a wild male's higher-quality songs were played to a subject in the more challenging treatment and his lower-quality songs were played to a subject in the less challenging treatment. It was essential to present each subject with a unique set of recorded songs because the number of stimulus sets is the effective sample size [70]. We played songs back at 70 dB 5 cm from the speaker, following a pattern of intense morning singing and intermittent afternoon/evening song (9 hr per day at an average rate of approximately 40 songs per hr). To ensure that the total duration of song each day was identical between treatment groups, and thus that we could conclude that any behavioral differences were elicited by the level of challenge and not the amount of song males heard, we included additional repetitions of less challenging songs, which tend to be shorter (see above), as necessary. Therefore, the treatments differed not only in their song quality, but also in their song repetition rates, with the more challenging playback treatment having slightly lower song repetition rates.

As part of the aforementioned study [16] we quantified the subjects' singing behavior by counting the number of songs each male produced from 05:00–09:00 each day, including the morning after playback stopped. We found that all males increased their singing effort throughout the week, but that males exposed to more challenging songs increased singing effort more quickly and to a much greater degree, resulting in an almost three-fold difference between groups in their singing rates on the last day of playback [16]. Further, males exposed to more challenging songs had approximately a 50% higher singing rate on the morning after playback ceased than males exposed to less challenging songs ([16]; Fig. 1). It is important to note that differences in singing behavior on the day after playback stopped are not reflective of real-time responses to playback stimuli. Rather, this behavioral difference reflects changes in behavioral state resulting from the prior week of experience with competitors' songs. However, at the time of brain collection the subjects' in the two treatment groups differed in both their competitive state and their very recent singing behavior. Therefore, we examined the simultaneous contributions of both the playback treatment (which elicited the change in singing over the entire week) and measures of each individual's most recent singing behavior to variation in monoamine measures. This approach permitted us to determine if brain differences reflected differences in the song treatment regardless of recent behavior (see Statistical procedures).

Tissue preparation and quantification of monoamines, metabolites and protein

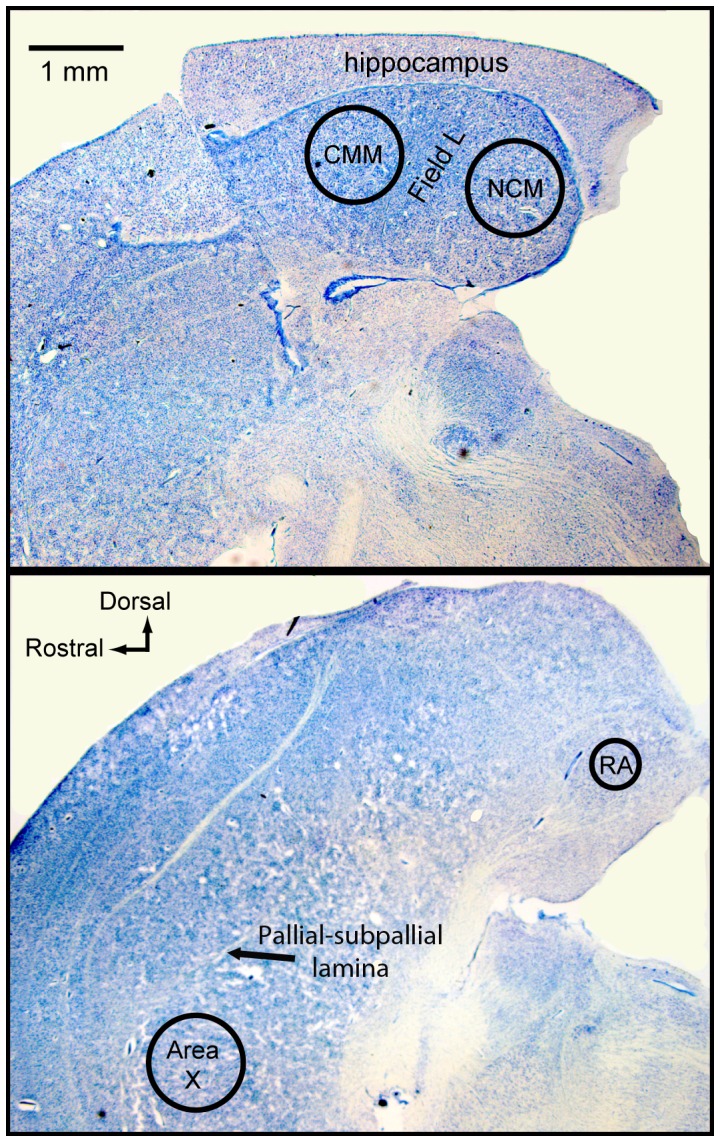

We sectioned the frozen, non-fixed hemisphere from each subject at 300 µm in the sagittal plane in a cryostat. We thaw mounted sections onto glass microscope slides and rapidly refroze the tissue on dry ice. Using micropunches (Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA, USA), we took one tissue sample from each of four brain regions – the NCM and the CMM of the auditory telencephalon; the principal nucleus of the anterior forebrain pathway of the song control system, area X, and the principal nucleus of the motor pathway, RA. We chose brain sections containing each region based on boundaries defined by Nissl-staining ([33] for protocol) in sections from the alternate, fixed hemisphere and comparison with a zebra finch atlas [71]. Although inter-hemispheric differences in anatomy and plane of section could lead to errors when using one hemisphere (the Nissl stained one) to guide dissection in the other, we used punches with diameters well below the diameters of the brain regions of interest to ensure that we included only tissue that was within the targeted brain region. Further, we selected areas to sample that were bounded by visible neuroanatomical markers in fresh frozen tissue (i.e., RA, area X) or that were sufficiently large that we were confident that a tissue punch would be well within the bounds of the region (i.e., the CMM, the NCM) as defined by the Nissl-stained contralateral sections. We collected 1-mm-diameter punches from the center of both the NCM and the CMM, the boundaries of which have been described [36], [72], in the most medial brain section (Fig. 3). We sampled area X by taking one 1-mm punch from each of two consecutive sections that were 300–900 µm lateral to the midline, and RA by taking one 0.7-mm punch from each of two consecutive sections 1500–2100 µm lateral to the midline (Fig. 3). We expelled tissue punches into 1.9 mL polypropylene microcentrifuge tubes, froze them on dry ice and stored them at −80°C until assay (ca. 6 weeks). Immediately before assay, we added 125 µL of mobile phase containing 1 pg/µL of isoproterenol to each tube containing a tissue micropunch. We sonicated the samples and then centrifuged them at 16,000 g for 16 min at 4°C. We drew off the supernatant and transferred it to an autosampler tube; 10 µL of supernatant from each sample was injected into the HPLC system.

Figure 3. Placement of Tissue Punches.

Photomicrographs of sagittal brain sections approximately 300 µm (upper panel) and 900 µm (lower panel) from the midline illustrating where micropunches of tissue were taken to quantify levels of norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, and their primary metabolites in the caudomedial mesopallium (CMM), the caudomedial nidopallium (NCM), area X, and the robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA; lower image). Images generated for illustration only.

In addition to quantifying the amount of norepinephrine in the auditory forebrain regions, dopamine in the song control nuclei, and serotonin from all of the brain regions of interest, we also quantified the amount of the monoamine principal metabolites, 3-methoxy-4-hydroxy-phenylglycol (hereafter norepinephrine metabolite), 3,4-dihydrophenylacetic acid (hereafter dopamine metabolite), and 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid (hereafter serotonin metabolite). We used an HTEC-500 complete stand-alone HPLC-ECD system (Eicom, San Diego, CA, USA) coupled with a Midas autosampler (Spark Holland, Netherlands). We separated compounds using an Eicompak SC-3ODS column (Eicom) and used a mobile phase (pH 3.5) consisting of citric acid (8.84 g), sodium acetate (3.10 g), sodium octyl sulfonate (215 mg), EDTA (5 mg), methanol (200 mL) and ultra pure water (800 mL; all compounds, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). We maintained the electrode potential at 750 mV with respect to the Ag/AgCl reference electrode. We prepared two standards with 1 pg/µL and 10 pg/µL of each of the 6 compounds of interest and used these two standard solutions to run a two-point standard curve at the beginning of each sample run (compounds listed above). We also included an internal standard, isoproterenol (Sigma-Aldrich), in each standard solution and tissue sample to identify any preparations from which sample was lost; no samples had significantly lower amounts of internal standard than expected.

Monoamines can be rapidly broken down into metabolites once they are secreted into the synapse and therefore their primary metabolites may serve as indices of monoamine metabolism. However, monoaminergic activity is a function of availability within the synapse, which is regulated by the rate of monoamine secretion and re-uptake, as well as catabolism. Thus, quantities of the monoamines themselves may reflect the amount of neuromodulators synthesized and stored pre-synaptically, or bound by metabolic or re-uptake enzymes within the synaptic cleft but not yet broken down or reabsorbed [73]. We quantified both the amounts of monoamines and their metabolites using high-pressure liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection, in an effort to understand how both monoamine availability and breakdown (hereafter referred to generally as monoaminergic activity) differed between the treatments. It should be remembered that monoaminergic activity results from the coordination of multiple cellular mechanisms, the subtlety of which cannot be captured by this experimental approach.

We calculated the amounts of each monoamine and metabolite by comparing the areas of the peaks of the compounds within each sample to those obtained from the two standard solutions that we used to generate the standard curve, using the peak area ratio function in PowerChrom software (eDAQ, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). Some peaks were not measurable and were omitted from the analysis (see degrees of freedom in Table 1). We then measured the protein content of each sample by dissolving the remaining protein pellet in 0.2 M NaOH (25 µL for 0.7 mm punch samples, 50 µL for 1 mm punch samples) and performing a Bradford protein-dye binding assay (Quickstart Bradford Protein Assay, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with bovine serum albumin as a standard on a µQuant microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). In a few cases the accuracy of the protein assay was poor. Because we did not have enough sample to repeat the assay, the amount of protein was estimated as the average amount of protein in the other samples from that brain region. This is an acceptable estimation because a standard micropunch was used and there was relatively little variation in protein quantities across tissue samples from a given brain region (e.g., 17 µg±4 µg in 0.7 mm punches from RA). We report the amounts of each compound of interest per mg of protein in the sample.

Table 1. Song playback and monoamine levels.

| Estimate | SEM | DF | t | P | Estimate | SEM | DF | t | P | ||

| NCM | |||||||||||

| Norepinephrine | Norepinephrine metabolite | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 511.956 | 83.785 | 7 | 6.110 | 192.192 | 30.017 | 7 | 6.403 | |||

| Level of song challenge | 11.162 | 46.522 | 6 | 0.240 | 0.818 | 53.467 | 64.461 | 5 | 0.829 | 0.445 | |

| Recent singing | −29.126 | 12.273 | 6 | −2.373 | 0.055* | −9.566 | 6.679 | 5 | −1.432 | 0.211 | |

| Serotonin | Serotonin metabolite | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 1218.784 | 205.999 | 7 | 5.916 | 390.097 | 81.743 | 7 | 4.772 | |||

| Level of song challenge | 295.378 | 226.932 | 5 | 1.302 | 0.250 | 77.006 | 83.812 | 6 | 0.919 | 0.394 | |

| Recent singing | −65.574 | 41.979 | 5 | −1.562 | 0.179 | −38.028 | 15.948 | 6 | −2.384 | 0.054* | |

| CMM | |||||||||||

| Norepinephrine | Norepinephrine metabolite | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 352.316 | 54.772 | 7 | 6.432 | 157.515 | 12.541 | 7 | 12.560 | |||

| Level of song challenge | −1.997 | 53.669 | 6 | −0.037 | 0.971 | 42.639 | 9.963 | 5 | 4.280 | 0.008 | |

| Recent singing | −7.307 | −7.307 | 6 | −0.627 | 0.558 | −4.837 | 2.448 | 5 | −1.976 | 0.105 | |

| Serotonin | Serotonin metabolite | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 1560.179 | 342.115 | 7 | 4.560 | 458.762 | 75.893 | 7 | 6.045 | 0.001 | ||

| Level of song challenge | 352.239 | 399.113 | 6 | 0.883 | 0.411 | 70.671 | 74.064 | 6 | 0.954 | 0.377 | |

| Recent singing | −80.477 | 68.015 | 6 | −1.183 | 0.282 | −39.538 | 10.069 | 6 | −2.192 | 0.070* | |

| Area X | |||||||||||

| Dopamine | Dopamine metabolite | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 2501.745 | 634.318 | 7 | 3.945 | 3704.655 | 622.71 | 7 | 5.949 | |||

| Level of song challenge | 12.276 | 759.228 | 6 | 0.017 | 0.988 | −382.886 | 1149.7 | 5 | −0.333 | 0.753 | |

| Recent singing | −0.861 | 1.361 | 6 | −0.633 | 0.550 | 3.572 | 1.862 | 5 | 1.919 | 0.113 | |

| Serotonin | Serotonin metabolite | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 70.670 | 12.674 | 7 | 5.576 | 66.553 | 22.639 | 7 | 2.940 | |||

| Level of song challenge | 5.155 | 18.726 | 6 | 0.276 | 0.792 | −11.264 | 18.087 | 5 | −0.623 | 0.561 | |

| Recent singing | −0.026 | 0.030 | 6 | −0.858 | 0.424 | 0.002 | 0.021 | 5 | 0.089 | 0.933 | |

| RA | |||||||||||

| Dopamine | Dopamine metabolite | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 478.072 | 106.086 | 7 | 4.506 | 131.799 | 22.375 | 7 | 5.891 | |||

| Level of song challenge | −231.336 | 97.502 | 6 | −2.373 | 0.055* | −16.104 | 16.946 | 6 | −0.950 | 0.379 | |

| Recent singing | 0.020 | 0.190 | 6 | 0.104 | 0.920 | −0.063 | 0.038 | 6 | −1.654 | 0.149 | |

| Serotonin | Serotonin metabolite | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 859.220 | 176.674 | 7 | 4.863 | 174.128 | 35.065 | 7 | 4.966 | |||

| Level of song challenge | −435.568 | 163.936 | 6 | −2.657 | 0.038 | −33.008 | 33.857 | 6 | −0.975 | 0.367 | |

| Recent singing | 0.065 | 0.217 | 6 | 0.297 | 0.776 | −0.093 | 0.050 | 6 | −1.852 | 0.113 | |

Effects of the song playback and a subject's own recent singing behavior on amounts of three monoamines and their primary metabolites (measured as pg/mg protein) in auditory processing and song control regions of the forebrain of male Lincoln's sparrows. Level of song challenge (i.e., treatment) was coded 0 for less challenging and 1 for more challenging. Statistically reliable effects (p<0.05) are indicated with bolded p values. Marginally reliable effect (p<0.07) are indicated with a single asterix (*).

Statistical procedures

Our data consisted of a hierarchically structured combination of fixed (e.g., song playback treatment) and random (e.g., chamber) effects, which may differ from one another in their correlation structure. Therefore we analyzed these data in a mixed, multilevel modeling framework using the software R 2.7.2 [74], which readily accommodates hierarchically structured combinations of fixed and random effects. We included the level of song challenge (i.e., the playback treatment) and the number of songs a male produced on the final morning before sacrifice as predictors in all models. We ran one model for each compound predicted to be of importance in each of the brain regions of interest. We used a general linear mixed model (GLMM; nlme package; [75]), which uses t-tests to test the null hypothesis that a coefficient equaled 0. We estimated parameters with restricted maximum likelihood (REML) and we modeled chamber as a random intercept and random coefficient on playback treatment in all cases. The song playback treatment in all models was coded 0 for less challenging and 1 for more challenging.

Results

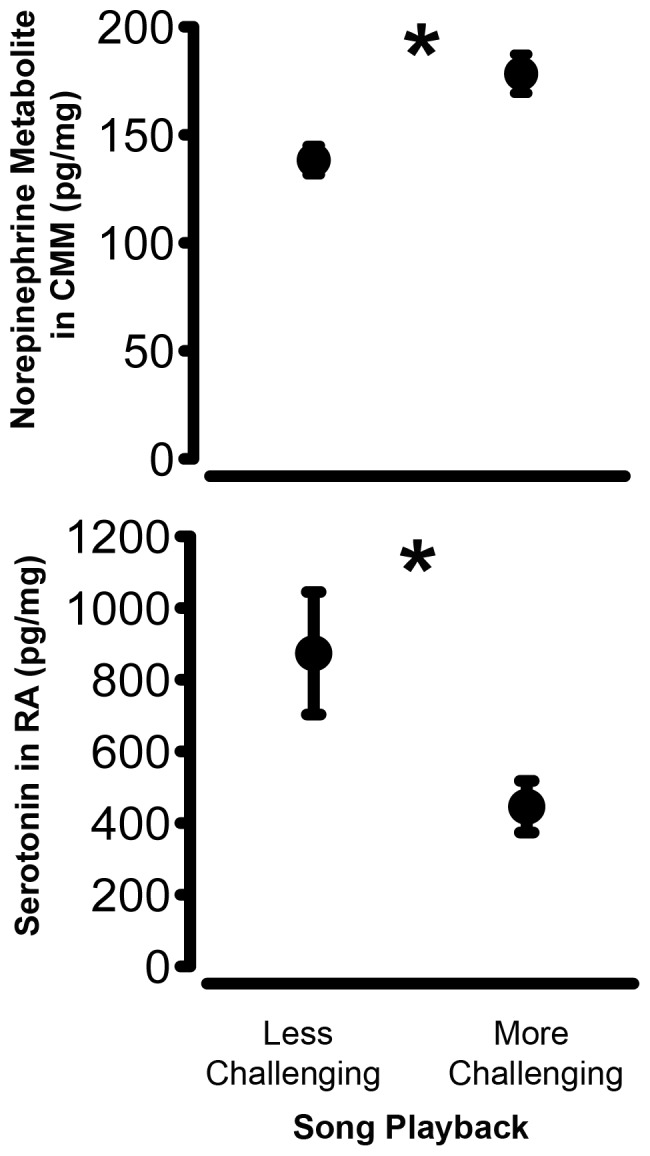

Males that had been exposed to more challenging songs for a week had higher levels of norepinephrine metabolite in an auditory processing region, the CMM, relative to males exposed to less challenging songs [GLMM, effect of level of song challenge, t = 4.280, p = 0.008; Fig. 4a; Table 1]. Additionally, males that had been exposed to the more challenging song treatment had lower levels of serotonin in RA [GLMM, effect of level of song challenge, t = −2.657, p = 0.038; Fig. 4b; Table 1]. For all the other compounds in all the other brain regions examined, we were unable to find reliable differences based on the level of song challenge males experienced for a week (all p>0.05, Table 1).

Figure 4. Treatment effects on forebrain monoamines.

The effects of the level of song challenge on the amount (mean pg/mg of protein ± SEM) of (a) norepinephrine metabolite in the caudomedial mesopallium (CMM) and (b) serotonin in the robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA).

We did not find any statistically significant relationships between a male's own singing effort the morning before sacrifice and the level of any compound of interest in any brain region examined (all p>0.05). However, because the playback treatment was positively associated with singing behavior, it cannot be ruled out that self-stimulation from a male's own singing may have contributed to the observed differences and future studies should evaluate this potential contribution to the observed treatment effects. Nonetheless, the present results indicate that the level of song challenge caused changes in monoamine and metabolite levels that cannot be explained by recent singing behavior.

Discussion

Male Lincoln's sparrows exposed to more challenging songs shift their competitive behavior to sing more over the period of a week [16]. We argue that the gradual change in behavior and the persistence of this behavioral difference on the day after playback ceased reflects a shift in the males' competitive state as a function of longer-term social conditions. Here, we show that males exposed to more challenging songs also had higher levels of norepinephrine metabolite, suggesting higher levels of norepinephrine breakdown, in a perceptual brain region specifically implicated in song discrimination and recognition, the CMM ([76], [77]; Fig. 4a). Additionally, these males had lower levels of serotonin in the principal motor nucleus within the song control pathway, RA (Fig. 4b). There were no reliable relationships between levels of monoamines or their metabolites and singing output immediately prior to sacrifice. Further, the relationships between the level of song challenge and the levels of monoamines and their metabolites was independent of the level of recent singing effort, indicating that the detected differences in monoamine levels could not be explained by fluctuations in this recent behavior. The association between some monoamines and the social treatment, combined with our previous report that this social treatment induces changes in competitive behavior [16] is consistent with the established role of the monoamines as modulators of sensory and motor processes underlying adaptive shifts in behavioral state. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that persistent variation in male-male competition reflected by the level of song challenge elicits concerted changes in at least two important monoamine neuromodulator systems within both perceptual and motor control brain regions.

The monoamines largely mediate neural plasticity underlying shifts in behavioral state by influencing the sensitivity or excitability (i.e., cellular properties) of target neurons [1], [7], [37]. Differences in behavioral state can be regulated by differences in monoaminergic activity over extended periods. For example, shifts in attention and motivation, differences in mood, mood disorders and behavioral pathologies such as schizophrenia are all associated with long-term differences in forebrain monoamine levels [2], [9], [78]. However, transient differences in monoamine levels may also alter synaptic properties and neural connectivity within the forebrain [1], [2], [78], [79] and the present experimental design would not have captured such transient actions of the monoamines. Thus, it is probable that there were additional differences in monoamine levels in the days prior to our measurements, and that some of these undetected monoaminergic differences contributed to neural plasticity and the ultimate behavioral shift that was observed, making the reported findings a conservative summary of treatment effects. Similarly, the experimental design could not discriminate between persistent differences and effects within the final day of the manipulation and thus we cannot know how long the differences we did detect may have persisted. Despite these caveats, the present study did find differences in the levels of monoamines and their metabolites in perceptual and song motor control brain regions, indicating that some monoaminergic changes occur in response to longer-term social conditions. Future studies manipulating monoamine levels across social contexts and timelines are needed to demonstrate if and how the differences detected in the present study are causally tied to changes in behavioral state, and to determine the timelines of such brain changes.

Effects of the level of song challenge on monoamines in regions of the auditory telencephalon

Neural activity in the NCM and the CMM occurs in response to hearing conspecific songs [44], [80], [81], varies as a function of qualitative differences among songs [76], [77], [82]–[84] and is influenced by recent experience [72], [85] and context [86]. The NCM in particular shows strong staining for dopamine beta hydroxylase, leading to the inference of strong noradrenergic innervation, likely from the locus coeruleus [87]. Across vertebrate taxa, norepinephrine plays a central role in focusing attention on relevant stimuli [4], [7] and in improving perceptual acuity in sensory brain regions [1], [7] including auditory processing regions [8], [39]. In birds, ablating noradrenergic inputs to the forebrain abolishes biased behavioral [38], [88] and neural [35] responses in the NCM and the CMM, to preferred signals. Further, exposure to persistent song playback affects norepinephrine secretion and metabolism in the auditory forebrain of female birds [36]. Collectively, this evidence supports the role of norepinephrine in modifying the sensitivity of neurons within these auditory brain regions as a function of social conditions, perhaps by increasing neural responsiveness to relevant cues [35].

Based on previous studies, the present finding of higher norepinephrine metabolite levels, and thus presumably norepinephrine metabolism, in the CMM of male birds exposed to more challenging songs (Fig. 4a) could reflect increased sensitivity and attention to song challenge [35], [38]. The absence of a concomitant increase in norepinephrine secretion in the NCM may be surprising because the NCM is implicated in the processing and memorization of song [89] and noradrenerigic activity is specifically implicated in this neuronal adaptation [90]. However, neurons in the NCM respond to novelty and neuronal activity in this brain region decreases with habituation [41], [81], [91]. Thus, it is possible that any differences between treatment groups in noradrenergic activity in the NCM occurred very quickly [90] as auditory memories were encoded and treatment differences in NCM were not detected due to the experimental timeline. It is equally possible that males in the two treatments groups, having been exposed to song playback for the same duration of time, encoded those auditory memories with equal fidelity despite the apparent difference in the saliency of the stimuli. In contrast to the NCM, CMM neurons may respond to familiar songs ([77], though see [81]). Given that the subjects had been exposed to the same set of recordings for 7 days, presumably making them familiar, it seems reasonable to anticipate greater changes in the CMM in response to such persistent challenge. Determining if and how norepinephrine secretion and metabolism in the CMM could in turn affect males' behavioral output will require manipulations of norepinephrine levels in the auditory forebrain. Because the caudomesopallium contains neurons that project to a central nucleus of the song control pathway (HVC) or the nearby nidopallium [92], [93], it is reasonable to hypothesize that norepinephrine's effects in the CMM could ultimately influence song output.

Effects of the level of song challenge on monoamines in nuclei of the song control system

Persistent playback of more challenging song reduced levels of serotonin in the principal nucleus of the song motor control pathway, RA, relative to playback of less challenging song (Fig. 4b). Nucleus RA, in concert with area X, is implicated in context-specific singing behavior [55], [56] that occurs on a temporal scale ranging from seasonal shifts in song output [94]–[96] to moment-to-moment changes in song quality associated with the presence of a female [55], [56]. While area X is thought to regulate shifts in the quality and stereotypy of song, the RA translates pre-motor signals from HVC and the anterior forebrain pathway into coordinated movements of the respiratory and syringeal muscles [55], [56], [97]. Both RA and area X receive catacholaminergic inputs from the dopaminergic center, the ventral tegmental area (VTA; [11], [37], [49]–[54]); and serotonergic innervation of the entire avian forebrain from the raphe nuclei is extensive [57].

There is strong evidence that neural activity in the VTA regulates context-specific activity in area X, and therefore RA [11], through dopaminergic inputs and that dopamine levels in these regions ultimately control song output [47], [48], [55], [56], [98]–[104]. However, the effect of the social treatment on dopamine levels in RA fell just short of statistical significance in the present study (p = 0.055; Table 1). Nor was there good evidence that singing immediately prior to sacrifice was correlated with levels of dopamine or its primary metabolite in area X (p = 0.113; Table 1). The absence of detectable variation in dopaminergic activity in area X, the brain region most frequently implicated in context-specific singing [11], is surprising but could be explained by the fact that previous studies of singing modulation focused on short-term mate attraction efforts in colonial birds (e.g., [56]). In contrast, the present study examined dopaminergic responses to persistent signals of male-male competition (not mate attraction) in a territorial species; subjects were exposed to equal durations of song playback that differed in the relative level of social challenge it reflected. Subjects did not differ in the quality of songs that they produced [16], a feature of singing behavior associated with shifts in mate attraction efforts and neural activity in area X [55], [56]. However, males did differ in the amount of song they produced, a measure associated with shifts in competitiveness, territoriality [29], [30], [32], [105], and neural activity in RA [55], [106], perhaps explaining the marginal treatment effect on dopamine levels in RA (Table 1). Though the present results are not robust, they do encourage future study of the effect of dopamine manipulations in RA on the rate of singing in territorial birds.

Given the role of RA in regulating song output, we expected that monoaminergic differences in this brain region would be correlated with recent motor output of song, independently of treatment. In particular, we expected levels of dopamine and serotonin metabolite to correlate positively with recent singing [47], [48], [62]–[64], [100], [101], [104], [107]. However, surprisingly, the most robust finding in this brain region was that the level of serotonin was explained by the level of song challenge (p = 0.038; Fig. 4b) and was not reliably associated with a male's own singing behavior in the hours before sacrifice. This result supports the conclusion that serotonin was differentially regulated within RA as a function of social experience. Given that there was no treatment effect on serotonin metabolite, elevated serotonin might be interpreted to reflect increased presynaptic levels or higher extracellular levels of this monoamine. Such a pattern could result from increased synthesis and sequestration presynaptically, or decreased activity of catabolic and re-uptake enzymes (e.g., monoamine oxidases and transporters) leaving more serotonin in the synapse. Though the absence of a concomitant treatment effect on serotonin metabolite is difficult to reconcile, increased serotonergic activity (i.e., decreased metabolite levels and in some cases decreased serotonin levels [108]) is associated with increased aggression across vertebrate species [15], [65], and singing behavior in the context of male-male competition is an aggressive behavior. In the present study, though we did not find an effect on metabolite, we did find decreased serotonin levels in males that were exposed to more challenging songs, who sang more, and were thus inferred to be in a more competitive behavioral state. Thus, the present findings are not completely inconsistent with the broader body of research on serotonergic regulation of aggression.

In addition to regulating aggressive behavior, serotonin is also reported to regulate vocalizations across taxa [62]–[64]. For example, pharmacological inhibition of serotonin reuptake (and thus presumably an elevated level of serotonin) is reported to suppress vocalization rate in several species [62]–[64]. This prior work is consistent with the present finding that males exposed to less challenging song, who sang less, had higher serotonin levels (though whether serotonin was elevated within the synapse or presynaptically cannot be determined in our study). Future studies manipulating serotonin levels and examining behavioral response to social challenge over time will clarify how serotonin might contribute to changes in competitive singing.

Conclusions

Collectively, the present data demonstrate that persistent differences in the level of song challenge known to elicit a change in competitive behavioral state in territorial male songbirds, also affect monoaminergic measures in perceptual and song motor control brain regions. These findings implicate monoamine-induced neural plasticity in achieving adaptive changes in behavioral state in response to longer-term shifts in social conditions. Further, they support the hypothesis that social cues affect multiple brain regions in different but perhaps coordinated ways to ultimately achieve adaptive shifts in behavior. Future manipulative experiments building upon these findings will elucidate the causal relationships between monoaminergic activity and socially-induced changes in behavioral state. As our understanding of the monoamine systems increases, there is ever growing need to examine concerted changes across neuromodulatory systems, interconnected brain regions, and timelines, in relation to environmental conditions and associated behavioral outcomes [109], [110]. Conducting this work in diverse wild species with different natural histories also contributes to our understanding of how selection processes have shaped the concerted brain mechanisms underlying the adaptive modulation of behavior in response to changing conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank MV Kessels for assistance in the field and with hand rearing birds, KG Salvante for training and assistance, DM Racke for managing the library of Lincoln's sparrows songs, and ZP McKay for animal husbandry. Thanks to KS Lynch and ED Jarvis for comments.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01 grant number NS055125 to KWS, NIH IRACDA funding and F32 grant number HD056981 to KBS, http://www.nih.gov), a UNC Award from the RJ Reynolds fund (http://www.zsr.org/history.htm) to KWS, and a Leon Speeckaert Fund from the King of Baudouin Foundation and the Belgian American Educational Foundation (http://www.kbfus.org/index.html?current=9&page=6&page2=9&lang=en) to SPC. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Gu Q (2002) Neuromodulatory transmitter systems in the cortex and their role in cortical plasticity. Neuroscience 111: 815–835 doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00026-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD (2003) The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res Rev 42: 33–84 doi:10.1016/S0165-0173(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hurley L, Devilbiss D, Waterhouse B (2004) A matter of focus: monoaminergic modulation of stimulus coding in mammalian sensory networks. Curr Opin Neurobiol 14: 488–495 doi:10.1016/j.conb.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD (2005) An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu Rev Neurosci 28: 403–450 doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Castelino CB, Ball GF (2005) A role for norepinephrine in the regulation of context-dependent ZENK expression in male zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata). Eur J Neurosci 21: 1962–1972 doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berridge CW (2008) Noradrenergic modulation of arousal. Brain Res Rev 58: 1–17 doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sara SJ (2009) The locus coeruleus and noradrenergic modulation of cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 10: 211–223 doi:10.1038/nrn2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cardin JA, Schmidt MF (2004) Noradrenergic inputs mediate state dependence of auditory responses in the avian song system. J Neurosci 24: 7745–7753 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1951-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Furth WR, Wolterink G, Van Ree JM (1995) Regulation of masculine sexual behavior: involvement of brain opiods and dopamine. Brain Res Rev 21: 162–184 doi:10.1016/0165-0173(96)82985-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berridge KC, Robinson TE (1998) What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Res Rev 28: 309–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kubikova L, Kostál L (2010) Dopaminergic system in birdsong learning and maintenance. J Chem Neuroanat 39: 112–123 doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harvey JA (2003) Role of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in learning. Learn Mem 10: 355–362 doi:10.1101/lm.60803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Williams GV, Rao SG, Goldman-Rakic PS (2002) The physiological role of 5-HT2A receptors in working memory. J Neurosci 22: 2843–2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Glanzman DL, Mackey SL, Hawkins RD, Dyke AM, Lloyd PE, et al. (1989) Depletion of serotonin in the nervous system of Aplysia reduces the behavioral enhancement of gill withdrawal as well as the heterosynaptic facilitation produced by tail shock. J Neurosci 9: 4200–4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferrari F, Palanza P, Parmigiani S, De Almeida RMM, Miczek KA (2005) Serotonin and aggressive behavior in rodents and nonhuman primates: predispositions and plasticity. Eur J Pharma 526: 259–273 doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sewall KB, Dankoski EC, Sockman KW (2010) Song environment affects singing effort and vasotocin immunoreactivity in the forebrain of male Lincoln's sparrows. Horm Behav 58: 544–553 doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catchpole CK, Slater PJB (1990) Bird Song: Biological Themes and Variations. Cambridge University Press. 264 p. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins S (2004) Vocal fighting and flirting: the functions of birdsong. In: Marler PR, Slabbekoorn H, editors. Nature's Music: the science of birdsong. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Catchpole CK (1980) Sexual selection and the evolution of complex songs among European warblers of the genus Acrocephalus . Behaviour 74: 149–166. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wasserman FE, Cigliano JA (1991) Song output and stimulation of the female in white-throated sparrows. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 29: 55–59 doi:10.1007/BF00164295. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hasselquist D, Bensch S, Von Schantz T (1996) Correlation between male song repertoire, extra-pair paternity and offspring survival in the great reed warbler. Nature 381: 229–232 doi:10.1038/381229a0. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gentner Hulse (2000) Female European starling preference and choice for variation in conspecific male song. Anim Behav 59: 443–458 doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Duffy DL, Ball GF (2002) Song predicts immunocompetence in male European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). Proc Biol Sci 269: 847–852 doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gil D, Gahr M (2002) The honesty of bird song: multiple constraints for multiple traits. Trends Ecol Evol 17: 133–141 doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02410-2. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Naguib M, Heim C, Gil D (2008) Early developmental conditions and male attractiveness in zebra finches. Ethology 114: 255–261 doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2007.01466.x. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mountjoy DJ, Lemon R (1991) Song as an attractant for male and female European starlings, and the influence of song complexity on their response. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 28: 97–100 doi:10.1007/BF00180986. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hurd PL, Enquist M (2005) A strategic taxonomy of biological communication. Anim Behav 70: 1155–1170 doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.02.014. [Google Scholar]

- 28. DuBois AL, Nowicki S, Searcy WA (2009) Swamp sparrows modulate vocal performance in an aggressive context. Biol Lett 5: 163–165 doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Godard R (1993) Tit for tat among neighboring hooded warblers. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 33: 45–50 doi:10.1007/BF00164345. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Olendorf R, Getty T, Scribner K, Robinson S (2004) Male red–winged blackbirds distrust unreliable and sexually attractive neighbours. Proc Biol Sci 271: 1033–1038 doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hyman J, Hughes M (2006) Territory owners discriminate between aggressive and nonaggressive neighbours. Anim Behav 72: 209–215 doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.01.007. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Akçay Ç, Wood WE, Searcy WA, Templeton CN, Campbell SE, et al. (2009) Good neighbour, bad neighbour: song sparrows retaliate against aggressive rivals. Animal Behaviour 78: 97–102 doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.03.023. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sockman KW, Salvante KG, Racke DM, Campbell CR, Whitman BA (2009) Song competition changes the brain and behavior of a male songbird. J Exp Biol 212: 2411–2418 doi:10.1242/jeb.028456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salvante KG, Racke DM, Campbell CR, Sockman KW (2010) Plasticity in singing effort and its relationship with monoamine metabolism in the songbird telencephalon. Dev Neurobiol 70: 41–57 doi:10.1002/dneu.20752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lynch KS, Ball GF (2008) Noradrenergic deficits alter processing of communication signals in female songbirds. Brain Behav Evol 72: 207–214 doi:10.1159/000157357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sockman KW, Salvante KG (2008) The integration of song environment by catecholaminergic systems innervating the auditory telencephalon of adult female European starlings. Devel Neurobio 68: 656–668 doi:10.1002/dneu.20611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Castelino CB, Schmidt MF (2010) What birdsong can teach us about the central noradrenergic system. J Chem Neuroanat 39: 96–111 doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Appeltants D, Del Negro C, Balthazart J (2002) Noradrenergic control of auditory information processing in female canaries. Behav Brain Res 133: 221–235 doi:10.1016/S0166-4328(02)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Manunta Y, Edeline J-M (2004) Noradrenergic induction of selective plasticity in the frequency tuning of auditory cortex neurons. J Neurophysiol 92: 1445–1463 doi:10.1152/jn.00079.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Appeltants D, Ball GF, Balthazart J (2001) The distribution of tyrosine hydroxylase in the canary brain: demonstration of a specific and sexually dimorphic catecholaminergic innervation of the telencephalic song control nuclei. Cell Tissue Res 304: 237–259 doi:10.1007/s004410100360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chew SJ, Mello C, Nottebohm F, Jarvis E, Vicario DS (1995) Decrements in auditory responses to a repeated conspecific song are long-lasting and require two periods of protein synthesis in the songbird forebrain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 3406–3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stripling R, Volman SF, Clayton DF (1997) Response modulation in the zebra finch neostriatum: relationship to nuclear gene regulation. J Neurosci 17: 3883–3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ribeiro S, Cecchi GA, Magnasco MO, Mello CV (1998) Toward a song code: evidence for a syllabic representation in the canary brain. Neuron 21: 359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bolhuis JJ, Zijlstra GG, Den Boer-Visser AM, Van Der Zee EA (2000) Localized neuronal activation in the zebra finch brain is related to the strength of song learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 2282–2285 doi:10.1073/pnas.030539097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gentner TQ, Margoliash D (2003) Neuronal populations and single cells representing learned auditory objects. Nature 424: 669–674 doi:10.1038/nature01731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Theunissen FE, Shaevitz SS (2006) Auditory processing of vocal sounds in birds. Curr Opin Neurobiol 16: 400–407 doi:10.1016/j.conb.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hara E, Kubikova L, Hessler NA, Jarvis ED (2007) Role of the midbrain dopaminergic system in modulation of vocal brain activation by social context. Eur J Neurosci 25: 3406–3416 doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sasaki A, Sotnikova TD, Gainetdinov RR, Jarvis ED (2006) Social context-dependent singing-regulated dopamine. J Neurosci 26: 9010–9014 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1335-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lewis JW, Ryan SM, Arnold AP, Butcher LL (1981) Evidence for a catecholaminergic projection to area X in the zebra finch. J Comp Neurol 196: 347–354 doi:10.1002/cne.901960212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bottjer SW (1993) The distribution of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the brains of male and female zebra finches. J Neurobiol 24: 51–69 doi:10.1002/neu.480240105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bottjer SW, Halsema KA, Brown SA, Miesner EA (1989) Axonal connections of a forebrain nucleus involved with vocal learning in zebra finches. J Comp Neurol 279: 312–326 doi:10.1002/cne.902790211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Soha JA, Shimizu T, Doupe AJ (1996) Development of the catecholaminergic innervation of the song system of the male zebra finch. J Neurobiol 29: 473–489 doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199604)29:4<473:: AID-NEU5>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Appeltants D, Ball G, Balthazart J (2002) The origin of catecholaminergic inputs to the song control nucleus RA in canaries. Neuroreport 13: 649–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gale SD, Person AL, Perkel DJ (2008) A novel basal ganglia pathway forms a loop linking a vocal learning circuit with its dopaminergic input. J Comp Neurol 508: 824–839 doi:10.1002/cne.21700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hessler NA, Doupe AJ (1999) Social context modulates singing-related neural activity in the songbird forebrain. Nat Neurosci 2: 209–211 doi:10.1038/6306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jarvis ED, Scharff C, Grossman MR, Ramos JA, Nottebohm F (1998) For whom the bird sings: context-dependent gene expression. Neuron 21: 775–788 doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Challet E, Miceli D, Pierre J, Repérant J, Masicotte G, et al. (1996) Distribution of serotonin-immunoreactivity in the brain of the pigeon (Columba livia). Anat Embryol 193: 209–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hurley LM, Pollak GD (2005) Serotonin shifts first-spike latencies of inferior colliculus neurons. J Neurosci 25: 7876–7886 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1178-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hurley LM, Pollak GD (1999) Serotonin differentially modulates responses to tones and frequency-modulated sweeps in the inferior colliculus. J Neurosci 19: 8071–8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hurley LM, Pollak GD (2001) Serotonin effects on frequency tuning of inferior colliculus neurons. J Neurophysiol 85: 828–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hurley LM, Thompson AM, Pollak GD (2002) Serotonin in the inferior colliculus. Hearing Res 168: 1–11 doi:10.1016/S0378-5955(02)00365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Newman JD, Winslow JT, Murphy DL (1991) Modulation of vocal and nonvocal behavior in adult squirrel monkeys by selective MAO-A and MAO-B inhibition. Brain Research 538: 24–28 doi:10.1016/0006-8993(91)90371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Winslow JT, Insel TR (1990) Serotonergic and catecholaminergic reuptake inhibitors have opposite effects on the ultrasonic isolation calls of rat pups. Neuropsychopharmacology 3: 51–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ten Eyck GR (2008) Serotonin modulates vocalizations and territorial behavior in an amphibian. Behav Brain Res 193: 144–147 doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Takahashi A, Quadros IM, Almeida RMM de, Miczek KA (2011) Brain serotonin receptors and transporters: initiation vs. termination of escalated aggression. Psychopharmacology 213: 183–212 doi:10.1007/s00213-010-2000-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nicholls TJ, Goldsmith AR, Dawson A (1988) Photorefractroiness in birds and comparison with mammals. Physiological Reviews 68: 133–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tchernichovski O, Mitra PP (2001) Sound Analysis Pro User Manual.

- 68. Caro SP, Sewall KB, Salvante KG, Sockman KW (2010) Female Lincoln's sparrows modulate their behavior in response to variation in male song quality. Behav Ecolo 21: 562–569 doi:10.1093/beheco/arq022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kroodsma DE, Byers BE, Goodale E, Johnson S, Liu W-C (2001) Pseudoreplication in playback experiments, revisited a decade later. Anim Behav 61: 1029–1033 doi:10.1006/anbe.2000.1676. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kroodsma DE (1990) Using appropriate experimental designs for intended hypotheses in `song' playbacks, with examples for testing effects of song repertoire sizes. Anim Behav 40: 1138–1150 doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80180-0. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nixdorf-Bergweiler BE, Bischof H-J (2007) A Stereotaxic Atlas Of The Brain Of The Zebra Finch, Taeniopygia Guttata With Special Emphasis On Telencephalic Visual And Song System Nuclei in Transverse and Sagittal Sections. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2348/.

- 72. Sockman KW, Gentner TQ, Ball GF (2002) Recent experience modulates forebrain gene-expression in response to mate-choice cues in European starlings. Proc Biol Sci 269: 2479–2485 doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Moore KE (1986) Drug-induced changes in the efflux of dopamine and serotonin metabolites from the brains of freely moving rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci 473: 303–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.R Development Core Team (2008) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available: http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Development Core Team (2012) Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models.

- 76. Gentner TQ, Hulse SH, Duffy D, Ball GF (2001) Response biases in auditory forebrain regions of female songbirds following exposure to sexually relevant variation in male song. J Neurobiol 46: 48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Terpstra NJ, Bolhuis JJ, Riebel K, Van der Burg JMM, Den Boer-Visser AM (2006) Localized brain activation specific to auditory memory in a female songbird. J Comp Neurol 494: 784–791 doi:10.1002/cne.20831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Castren E (2005) Is mood chemistry? Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 241–246 doi:10.1038/nrn1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Harding CF, Barclay SR, Waterman SA (1998) Changes in catecholamine levels and turnover rates in hypothalamic, vocal control, and auditory nuclei in male zebra finches during development. J Neurobiol 34: 329–346 doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199803)34:4<329:: AID-NEU4>3.0.CO;2-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mello CV, Vicario DS, Clayton DF (1992) Song presentation induces gene expression in the songbird forebrain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 6818–6822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Bolhuis JJ, Gahr M (2006) Neural mechanisms of birdsong memory. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 347–357 doi:10.1038/nrn1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Eda-Fujiwara H, Satoh R, Bolhuis JJ, Kimura T (2003) Neuronal activation in female budgerigars is localized and related to male song complexity. Eur J Neurosci 17: 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Maney DL, Goode CT, Lange HS, Sanford SE, Solomon BL (2008) Estradiol modulates neural responses to song in a seasonal songbird. J Comp Neurolo 511: 173–186 doi:10.1002/cne.21830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Leitner S, Voigt C, Metzdorf R, Catchpole CK (2005) Immediate early gene (ZENK, Arc) expression in the auditory forebrain of female canaries varies in response to male song quality. J Neurobiol 64: 275–284 doi:10.1002/neu.20135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sockman KW, Gentner TQ, Ball GF (2005) Complementary neural systems for the experience-dependent integration of mate-choice cues in European starlings. J Neurobiol 62: 72–81 doi:10.1002/neu.20068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kruse AA, Stripling R, Clayton DF (2004) Context-specific habituation of the zenk gene response to song in adult zebra finches. Neurobiol Learn Mem 82: 99–108 doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mello CV, Pinaud R, Ribeiro S (1998) Noradrenergic system of the zebra finch brain: immunocytochemical study of dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. J Comp Neurol 400: 207–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Riters LV, Pawlisch BA (2007) Evidence that norepinephrine influences responses to male courtship song and activity within song control regions and the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus in female European starlings. Brain Res 1149: 127–140 doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Gobes SMH, Bolhuis JJ (2007) Birdsong memory: A neural dissociation between song recognition and production. Curr Biol 17: 789–793 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Velho TAF, Lu K, Ribeiro S, Pinaud R, Vicario D, et al. (2012) Noradrenergic control of gene expression and long-term neuronal adaptation evoked by learned vocalizations in songbirds. PLoS One 7 Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3344865/. Accessed 2012 Nov 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Chew SJ, Vicario DS, Nottebohm F (1996) A large-capacity memory system that recognizes the calls and songs of individual birds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 1950–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Bauer EE, Coleman MJ, Roberts TF, Roy A, Prather JF, et al. (2008) A synaptic basis for auditory-vocal integration in the songbird. J Neurosci 28: 1509–1522 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3838-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Akutagawa E, Konishi M (2010) New brain pathways found in the vocal control system of a songbird. J Comp Neurol 518: 3086–3100 doi:10.1002/cne.22383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Nottebohm F (1981) A brain for all seasons: cyclical anatomical changes in song control nuclei of the canary brain. Science 214: 1368–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Tramontin AD, Brenowitz EA (2000) Seasonal plasticity in the adult brain. Trends Neurosci 23: 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Ball GF, Balthazart J (2010) Seasonal and hormonal modulation of neurotransmitter systems in the song control circuit. J Chem Neuroanat 39: 82–95 doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Nottebohm F, Stokes TM, Leonard CM (1976) Central control of song in the canary, Serinus canarius . J Comp Neurol 165: 457–486 doi:10.1002/cne.901650405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Maney DL, Ball GF (2003) Fos-like immunoreactivity in catecholaminergic brain nuclei after territorial behavior in free-living song sparrows. J Neurobiol 56: 163–170 doi:10.1002/neu.10227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Riters LV, Teague DP, Schroeder MB, Cummings SE (2004) Vocal production in different social contexts relates to variation in immediate early gene immunoreactivity within and outside of the song control system. Behav Brain Res 155: 307–318 doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Heimovics SA, Riters LV (2008) Evidence that dopamine within motivation and song control brain regions regulates birdsong context-dependently. Physiol & Behav 95: 258–266 doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Schroeder MB, Riters LV (2006) Pharmacological manipulations of dopamine and opioids have differential effects on sexually motivated song in male European starlings. Physiol & Behav 88: 575–584 doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Yanagihara S, Hessler NA (2006) Modulation of singing-related activity in the songbird ventral tegmental area by social context. Eur J Neurosci 24: 3619–3627 doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Huang Y-C, Hessler NA (2008) Social modulation during songbird courtship potentiates midbrain dopaminergic neurons. PLoS ONE 3: e3281 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Rauceo S, Harding CF, Maldonado A, Gaysinkaya L, Tulloch I, et al. (2008) Dopaminergic modulation of reproductive behavior and activity in male zebra finches. Behav Brain Res 187: 133–139 doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Hyman J, Hughes M, Searcy WA, Nowicki S (2004) Individual variation in the strength of territory defense in male song sparrows: correlates of age, territory tenure, and neighbor aggressiveness. Behaviour 141: 15–27 doi:10.1163/156853904772746574. [Google Scholar]

- 106. Brainard MS, Doupe AJ (2002) What songbirds teach us about learning. Nature 417: 351–358 doi:10.1038/417351a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Wood WE, Lovell PV, Mello CV, Perkel DJ (2011) Serotonin, via HTR2 receptors, excites neurons in a cortical-like premotor nucleus necessary for song learning and production. J Neurosci 31: 13808–13815 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2281-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Van der Vegt BJ, Lieuwes N, Cremers TIF, De Boer SF, Koolhaas JM (2003) Cerebrospinal fluid monoamine and metabolite concentrations and aggression in rats. Hormones and Behavior 44: 199–208 doi:10.1016/S0018-506X(03)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Florvall L, Ask AL, Ogren SO, Ross SB (1978) Selective monoamine oxidase inhibitors. 1. Compounds related to 4-aminophenethylamine. J Med Chem 21: 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Datla KP, Bhattacharya SK (1990) Effect of selective monoamine oxidase A and B inhibitors on footshock induced aggression in paired rats. Indian J Exp Biol 28: 742–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]