Abstract

The orexigenic neuropeptide melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH), a product of Pmch, is an important mediator of energy homeostasis. Pmch-deficient rodents are lean and smaller, characterized by lower food intake, body-, and fat mass. Pmch is expressed in hypothalamic neurons that ultimately are components in the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) drive to white and interscapular brown adipose tissue (WAT, iBAT, respectively). MCH binds to MCH receptor 1 (MCH1R), which is present on adipocytes. Currently it is unknown if Pmch-ablation changes adipocyte differentiation or sympathetic adipose drive. Using Pmch-deficient and wild-type rats on a standard low-fat diet, we analyzed dorsal subcutaneous and perirenal WAT mass and adipocyte morphology (size and number) throughout development, and indices of sympathetic activation in WAT and iBAT during adulthood. Moreover, using an in vitro approach we investigated the ability of MCH to modulate 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation. Pmch-deficiency decreased dorsal subcutaneous and perirenal WAT mass by reducing adipocyte size, but not number. In line with this, in vitro 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation was unaffected by MCH. Finally, adult Pmch-deficient rats had lower norepinephrine turnover (an index of sympathetic adipose drive) in WAT and iBAT than wild-type rats. Collectively, our data indicate that MCH/MCH1R-pathway does not modify adipocyte differentiation, whereas Pmch-deficiency in laboratory rats lowers adiposity throughout development and sympathetic adipose drive during adulthood.

Introduction

Adipocytes not only store excess energy (as triglycerides), but also function as endocrine cells that take part in the regulation of energy homeostasis. Obesity, characterized by excess energy stored in white adipose tissue (WAT), reflects the cumulative sum of the excess energy intake over energy expenditure over time [1]. The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) innervates both WAT and interscapular brown adipose tissue (iBAT), and is the primary initiator of lipolysis through its principal catecholaminergic neurotransmitter norepinephrine [2], [3], [4], [5]. Thus, in general, chronic sympathetic activity increases the fuel availability through increased lipid mobilization in WAT. Several central nervous system (CNS) circuits modulate SNS outflow to WAT, including leptin [6], insulin [7], [8], ghrelin [9], neuropeptide Y [10], and melanocortins [11], all of which affect adipose metabolism.

The hypothalamic orexigenic neuropeptide melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH), derived from Pmch, is an important effector of energy intake and expenditure [12], [13], [14]. Pmch-deficient rats are lean, characterized by lower food intake, body- and fat mass, and decreased energy expenditure [15]. MCH binds to MCH receptor 1 (MCH1R) [16], [17], [18]. Rodents only express MCH1R, whereas humans also express a second MCH receptor, MCH2R [19].

Retrograde viral transneuronal tract tracing studies have identified Pmch neurons in the lateral hypothalamus amongst other neurons as part of the central SNS outflow to WAT and iBAT [20], [21], [22]. Furthermore, MCH1Rs are expressed in isolated rat adipocytes and murine 3T3-L1 (pre)-adipocytes [23], [24]. In 3T3-L1 (pre)-adipocytes, MCH facilitates migration [25], activates signaling pathways [24], and regulates leptin synthesis [23]. On the contrary, MCH has no direct effect on adipocyte lipolysis [26]. Recently, an elegant study demonstrated that central activation of MCH1R in wild-type rats increases fat deposition in WAT via suppression of sympathetic drive [27].

Currently it is unknown whether chronic loss of MCH-signaling affects adipocyte differentiation or sympathetic adipose drive. Using Pmch-deficient [15] and wild-type control rats, we analyzed dorsal subcutaneous and perirenal WAT mass and adipocyte morphology throughout development. In addition, using an in vitro approach we investigated the ability of MCH to modulate 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation. Finally, norepinephrine turnover was measured as an index of sympathetic adipose drive during adulthood. Our data reveal that the MCH/MCH1R-pathway has no or a very minor role in white adipocyte differentiation Finally, our findings reveal that Pmch-deficiency in the rat lowers sympathetic adipose drive. The latter adaptation potentially favors adipose lipid deposition during the negative energy balance resulting from Pmch-deficiency.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Information

The Animal Care Committee of the Royal Dutch Academy of Science approved all experiments according to the Dutch legal ethical guidelines.

Rats, Housing, and Diet

Experimental wild-type (WT) and Pmch-deficient (HOM) littermate rats were generated using a heterozygous breeding strategy [15]. Two rats were housed together, unless noted otherwise, under controlled experimental conditions (12 h light/dark cycle, light period 0600–1800, 21±1°C, ∼60% relative humidity). A standard chow diet (RM3; 62% kcal from carbohydrate, 27% kcal from protein, 11% kcal from fat, 3.33 kcal/g AFE, SDS, Witham, United Kingdom) and water were provided ad libitum unless noted otherwise. All rats had access to home-cage enrichment (red rat retreat [Plexx, Elst, the Netherlands] and aspen gnaw brick [Technilab-BMI, Someren, the Netherlands]), unless noted otherwise. Genotyping was done as previously described [15], and genotypes were reconfirmed when experimental procedures were completed. Only male rats were used in this study.

WAT Mass and Morphology

After measuring body mass, rats were sacrificed at PND 40, 60, or 120 by asphyxiation followed by decapitation. The left and right dorsal subcutaneous WAT (dWAT) and perirenal (pWAT) fat pads, the left lateral liver lobe (as a indication of liver mass), and the adrenal glands were isolated and weighed, and adipose tissue volume was measured. WAT samples were collected in 4% formaldehyde, rotated overnight at room temperature, rinsed with 70% ethanol for 2 h, 96% ethanol for 2 h, twice with 100% ethanol for 1.5 h, 2 h in xylene, and embedded in paraffin overnight. Samples were then cut in 14 µm sections and stained with eosin. Ten sections/animal were cut at positions distributed equally throughout the WAT pad to minimize for local effects, and one picture was obtained per section. Images were captured with an Axioplan 2 microscope (Zeiss). Subsequently, average adipocyte cell diameter was measured using NIH ImageJ software. Using the average adipocyte cell diameter, adipose tissue volume, and correcting for the percentage of non-adipocyte tissue, an estimated number of total adipocyte cells was calculated. In a separate cohort of rats, after measuring body mass, rats were sacrificed at PND 140 by asphyxiation and decapitation, and iBAT was isolated and weighed.

Hormone Measurements

WT and HOM rats were sacrificed at PND 40, 60, or 120 by asphyxiation and decapitation, and whole blood was collected. Blood samples were allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min and centrifuged at 2150 rcf for 15 min at 4°C. Serum samples were then aliquoted and stored at −80°C until analysis. Serum leptin levels were measured in duplicate using a leptin ELISA (EZRL-83K; Linco Research, St. Charles, Missouri, USA), as previously described [15].

In vitro Differentiation of 3T3-L1 Cells and FABP4 Western Blot

Differentiation assays and Western blotting on murine 3T3-L1 cells were performed as described earlier [28], [29]. Antibodies used for Western blot analysis were: anti-FABP4 (sc18661; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and anti-Tubulin (ab6046; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA).

NETO and Tissue Preparation

NE turnover (NETO; an index of sympathetic activation) was measured using the α-methyl-p-tyrosine (AMPT) method [30], [31]. AMPT methyl ester hydrochloride (Sigma Aldrich, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands) was freshly prepared by first adding an aliquot of glacial acetic acid (1 µl/mg AMPT) and then diluting to the final concentration with 0.15 M NaCl. The pH was set to 7.0 using 5 M NaOH. At the beginning of the experiment, rats within the same genotype were paired based on body weight. At PND 153, half of the rats were untreated and sacrificed at t = 0 h to obtain baseline tissue NE content, whereas the paired other half was injected intraperitoneal (IP) with AMPT (250 mg AMPT per kilogram; 25 mg/ml) between 0900 and 1200. AMPT-treated rats received a second IP AMPT dose (125 mg/kg body mass; 12.5 mg/ml) 2 h after the initial AMPT injection to assure the maintenance of tyrosine hydroxylase inhibition. AMPT-treated rats were sacrificed 4 h after the initial AMPT injection by decapitation without anesthesia, after which dWAT, pWAT, epididymal WAT (eWAT), and iBAT were rapidly dissected, weighed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until assayed for NE content by high pressure liquid chromatography to determine NE content and NETO was subsequently calculated as previously [30]. Before the NETO experiment, rats were handled and sham-injected daily during 7 d to minimize handling/stress-induced increases in SNS activity during the experiment.

Ucp1 and Adrb3 mRNA Expression

iBAT mRNA expression was analyzed as previously described [15], using the following primers: uncoupling protein-1 (Ucp1), F: TCAGC TTTGC TTCCC TCAGG ATTG, R: AGCCG AGATC TTGCT TCCCA AAGA; β3-adrenoceptor (Adrb3), F: AGTCC ACCGC TCAAC AGGTT TGAT, R: AGCTT CCTTG CTGGA TCTTC ACG.

Data Analysis

Data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. All data were analyzed using a commercially available statistical program (SPSS for Macintosh, version 16.0) and were controlled for normality and homogeneity. All data were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. The null hypothesis was rejected at the 0.05 level.

Results

Chronic Pmch-deficiency Lowers Adipose Mass During Rat Development

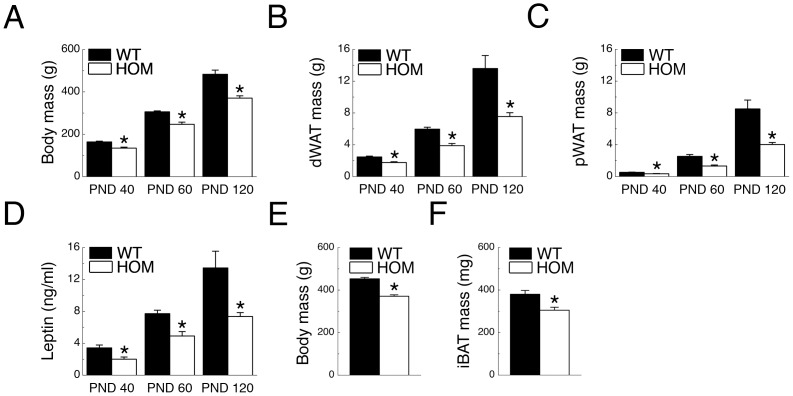

Body-, dWAT-, and pWAT mass was analyzed at PND 40, 60, and 120. At all three time-points, HOM rats had lower body mass than WT rats (Ps <0.05; Fig. 1A). Mirroring body mass, HOM rats had lower dWAT and pWAT mass than WT rats at all three time-points (Ps <0.05; Figs. 1B and 1C, respectively). HOM rats had lower serum leptin concentrations than WT rats at PND 40, 60, and 120, mirroring lower adiposity levels (Ps <0.05; Fig. 1D). In a separate cohort we analyzed iBAT mass at PND 140. HOM rats had lower body- and iBAT mass than WT rats (Ps <0.05; Figs. 1E and 1F).

Figure 1. Pmch-deficiency lowers body- and fat mass during development.

(A) Body mass (BM), (B) dWAT mass, (C) pWAT mass, and (D) serum leptin concentrations in WT and HOM rats (n = 8–15/group) at postnatal (PND) days 40, 60, and 120, and (E) body mass and (F) iBAT mass in WT and HOM rats (n = 15–19/group) at PND 147. *P<0.05 vs WT.

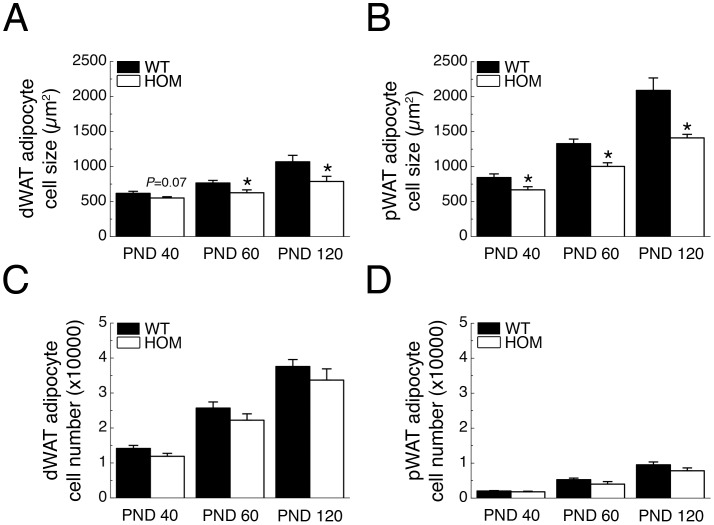

Chronic Pmch-deficiency Decreases Adipocyte Cell Size in vivo

HOM rats had lower WAT mass than WT rats, which can result from changes in adipocyte size, cell number or both. Therefore, we analyzed dWAT and pWAT adipocyte cell size and number in WT and HOM rats at PND 40, 60, and 120. HOM rats had smaller dWAT and pWAT adipocyte cell size than WT rats at PND 40, 60 and 120 (Ps <0.05; except for dWAT PND40, P = 0.07; Figs. 2A and 2B, respectively). dWAT and pWAT adipocyte cell number, however, did not differ significantly between genotypes at PND 40, 60 and 120 (Ps >0.05; Figs. 2C and 2D, respectively).

Figure 2. Pmch-deficiency decreases white adipocyte size.

(A) dWAT- (B) and pWAT adipocyte cell size, (C) dWAT- and (D) pWAT adipocyte cell number of WT and HOM rats (n = 8–15/group) at PND 40, 60, and 120. *P<0.05 vs WT.

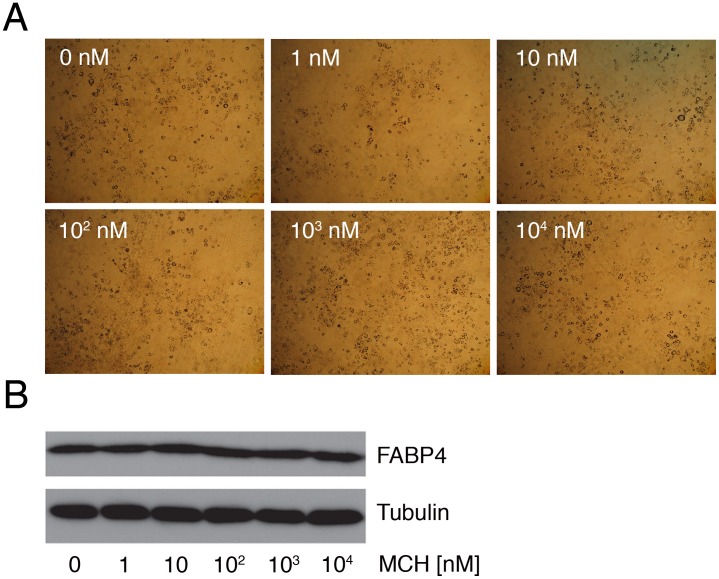

MCH does not Affect 3T3-L1 Adipocyte Differentiation in vitro

MCH1Rs are expressed in isolated rat adipocytes and murine 3T3-L1 (pre)-adipocytes [23], [24]. Therefore, we investigated if MCH can modulate 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation in vitro. Treatment of differentiating 3T3-L1 cells with MCH (1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 µM, or 10 µM) had no visible effects on adipocyte differentiation as visualized by Oil-red-O staining (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, protein analysis for FABP4, an indicator of adipocyte differentiation [32], confirmed no effect of MCH on 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation in vitro (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. MCH does not modify in vitro 3T3-L1 cell differentiation.

(A) 3T3-L1 cell differentiation after 7-day administration of 1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 µM, or 10 µM MCH as visualized by Oil-red-O staining (x20 magnification). (B) Western blot analysis for FABP4 (also known as aP2). Tubulin was used to control for input. Assays were performed in triplicate.

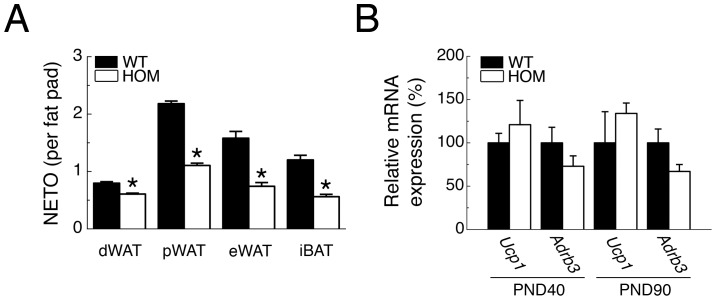

Chronic Pmch-deficiency Decreases Sympathetic Drive to Adipose Tissue

Retrograde viral transneuronal tract tracing studies have identified Pmch neurons in the lateral hypothalamus amongst other neurons as part of the central SNS outflow to WAT or iBAT [20], [21], [22]. Therefore we investigated if Pmch-deficiency changes the sympathetic drive to adipose tissue by analyzing NETO, an index of sympathetic activation. NETO is presented on a whole-organ basis to reflect the overall sympathetic drive and physiological impact for each tissue. HOM rats had lower NETO than WT rats in dWAT, pWAT, eWAT, and IBAT (Fig. 4A). We also analyzed mRNA expression levels of uncoupling protein-1 (Ucp1) and the β3-adrenoceptor (Adrb3) in iBAT, which did not differ significantly between genotypes at PND40 or 90 (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Pmch-deficiency lowers sympathetic adipose drive.

(A) NETO in dWAT, pWAT, eWAT, and iBAT of WT and HOM rats at PND 153 (n = 8–11/group). (B) Relative mRNA expression of Uncoupling Protein 1 (Ucp1) and β3-adrenoceptor (Adrb3) in iBAT of WT and HOM rats at PND 40 (left) and 90 (right) (n = 5–6/group). *P<0.05 vs WT.

Discussion

The present data demonstrate that chronic loss of MCH-signaling in the rat lowers adiposity throughout development and sympathetic adipose drive during adulthood, whereas adipocyte differentiation was unaffected during development.

Our observations that adult HOM rats have lower body mass, adiposity, and serum leptin levels than WT rats are in agreement with earlier observations [15]. Furthermore, we now demonstrate that these changes are already present in HOM rats at PND 40 and 60. Because HOM rats have decreased WAT mass and MCH1Rs are expressed on adipocytes, we investigated whether Pmch-deficiency had an effect on adipocyte number and size. In vivo, we observed robust differences in WAT adipocyte cell size, but no significant differences in adipocyte cell number, and in vitro we observed no effect of MCH administration on 3T3-L1 differentiation. In sum, our data suggest no major role for MCH/MCH1R-mediated signaling in adipocyte differentiation. In humans, however, this does not exclude a functional role for MCH/MCH2R-mediated signaling, as MCH2R is present in adipose tissue at significant levels and modulates adipocyte differentiation during an in vitro cell-based approach [33], [34].

A key observation of the present study is that adult HOM rats have lower sympathetic adipose drive, which corresponds with earlier observations that HOM rats have lower energy expenditure [15]. A decrease in energy expenditure could result from the hypophagic character of HOM rats [15], [35], as acute MCH1R agonism only affects energy expenditure in a feeding-dependent manner [36]. The SNS controls adipocyte lipolysis and several other metabolic responses through norepinephrine-mediated activation of the β3-adrenoceptor (Adrb3) [37]. Here we observed that iBAT Ucp1 expression, which is downstream of β3-adrenoceptor activation, was not significantly changed between genotypes at PND40 and 90. At these time points iBAT Adrb3 expression was slightly lower in HOM rats compared to WT rats, although not significantly, which is in line with the lower sympathetic drive to iBAT [38].

Recently it was demonstrated that 7-day intracerebroventricular infusion of MCH in wild-type rats increases fat deposition in WAT via suppression of sympathetic drive [27]. Surprisingly, despite different experimental approaches (chronic loss of Pmch versus pharmacological central administration of MCH), this finding supports the lower sympathetic adipose drive observed in the present study. Because MCH stimulates caloric intake [13], it is not unexpected that central MCH administration also stimulates lipid storage through direct modulation of adipocyte metabolism [27], overall promoting a positive energy balance. Pmch-deficiency, however, results in a negative energy balance and a similar reduction of sympathetic adipose drive. We suggest that the latter adaptation potentially favors adipose lipid deposition during this negative energy balance. Furthermore, chronic absence of MCH-signaling in our rat model has significant effects on physiology, including lower leptin levels in the circulation (this study and [15]) and lower hypothalamic Pro-opiomelanocortin (Pomc) mRNA expression during adulthood [15]. Central leptin signaling in the mediobasal hypothalamus can inhibit WAT lipogenesis through a sympathetic route [6], and activation of central melanocortin receptors increases iBAT NETO [30]. Thus, reduced central leptin- and melanocortin signaling could contribute to the lower adipose SNS activity in HOM rats, aiding in the promotion of a positive energy balance.

The orexigenic hypothalamic neuropeptide MCH/MCH1R-system has been the subject of many studies (for review see: [13], [14]), as functional inhibition of MCH, MCH1R, or a combination of both might result in an anti-obesity treatment [39]. Here we show in the rat that Pmch-deficiency lowers sympathetic adipose drive during adulthood. Understanding the mechanisms how Pmch-deficiency changes the autonomic balance might further help the development of a potential anti-obesity treatment based on the MCH/MCH1R system.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Andries Kalsbeek for critical reading of the manuscript and for suggested improvements.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R37 Dk35254 to TJB and by the European Science Foundation EURYI to EC. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Hirsch J (1997) Obesity. N Engl J Med 337: 396–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Slavin BG, Ballard KW (1978) Morphological studies on the adrenergic innervation of white adipose tissue. Anat Rec 191: 377–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wirsen C, Hamberger B (1967) Catecholamines in brown fat. Nature 214: 625–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartness TJ, Bamshad M (1998) Innervation of mammalian white adipose tissue: implications for the regulation of total body fat. Am J Physiol 275: R1399–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fredholm BB, Karlsson J (1970) Metabolic effects of prolonged sympathetic nerve stimulation in canine subcutaneous adipose tissue. Acta Physiol Scand 80: 567–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buettner C, Muse ED, Cheng A, Chen L, Scherer T, et al. (2008) Leptin controls adipose tissue lipogenesis via central, STAT3-independent mechanisms. Nat Med 14: 667–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koch L, Wunderlich FT, Seibler J, Konner AC, Hampel B, et al. (2008) Central insulin action regulates peripheral glucose and fat metabolism in mice. J Clin Invest 118: 2132–2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scherer T, O'Hare J, Diggs-Andrews K, Schweiger M, Cheng B, et al. (2011) Brain insulin controls adipose tissue lipolysis and lipogenesis. Cell Metab 13: 183–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Theander-Carrillo C, Wiedmer P, Cettour-Rose P, Nogueiras R, Perez-Tilve D, et al. (2006) Ghrelin action in the brain controls adipocyte metabolism. J Clin Invest 116: 1983–1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zarjevski N, Cusin I, Vettor R, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Jeanrenaud B (1994) Intracerebroventricular administration of neuropeptide Y to normal rats has divergent effects on glucose utilization by adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. Diabetes 43: 764–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nogueiras R, Wiedmer P, Perez-Tilve D, Veyrat-Durebex C, Keogh JM, et al. (2007) The central melanocortin system directly controls peripheral lipid metabolism. J Clin Invest 117: 3475–3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Richard D (2007) Energy expenditure: a critical determinant of energy balance with key hypothalamic controls. Minerva Endocrinol 32: 173–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pissios P, Bradley RL, Maratos-Flier E (2006) Expanding the scales: The multiple roles of MCH in regulating energy balance and other biological functions. Endocr Rev 27: 606–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pissios P (2009) Animals models of MCH function and what they can tell us about its role in energy balance. Peptides 30: 2040–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mul JD, Yi CX, van den Berg SA, Ruiter M, Toonen PW, et al. (2010) Pmch expression during early development is critical for normal energy homeostasis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E477–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saito Y, Nothacker HP, Wang Z, Lin SH, Leslie F, et al. (1999) Molecular characterization of the melanin-concentrating-hormone receptor. Nature 400: 265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chambers J, Ames RS, Bergsma D, Muir A, Fitzgerald LR, et al. (1999) Melanin-concentrating hormone is the cognate ligand for the orphan G-protein-coupled receptor SLC-1. Nature 400: 261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lembo PM, Grazzini E, Cao J, Hubatsch DA, Pelletier M, et al. (1999) The receptor for the orexigenic peptide melanin-concentrating hormone is a G-protein-coupled receptor. Nat Cell Biol 1: 267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tan CP, Sano H, Iwaasa H, Pan J, Sailer AW, et al. (2002) Melanin-concentrating hormone receptor subtypes 1 and 2: species-specific gene expression. Genomics 79: 785–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanley S, Pinto S, Segal J, Perez CA, Viale A, et al.. (2010) Identification of neuronal subpopulations that project from hypothalamus to both liver and adipose tissue polysynaptically. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21. Oldfield BJ, Giles ME, Watson A, Anderson C, Colvill LM, et al. (2002) The neurochemical characterisation of hypothalamic pathways projecting polysynaptically to brown adipose tissue in the rat. Neuroscience 110: 515–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adler ES, Hollis JH, Clarke IJ, Grattan DR, Oldfield BJ (2012) Neurochemical characterization and sexual dimorphism of projections from the brain to abdominal and subcutaneous white adipose tissue in the rat. J Neurosci 32: 15913–15921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bradley RL, Kokkotou EG, Maratos-Flier E, Cheatham B (2000) Melanin-concentrating hormone regulates leptin synthesis and secretion in rat adipocytes. Diabetes 49: 1073–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bradley RL, Mansfield JP, Maratos-Flier E, Cheatham B (2002) Melanin-concentrating hormone activates signaling pathways in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283: E584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cook LB, Shum L, Portwood S (2010) Melanin-concentrating hormone facilitates migration of preadipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 320: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bradley RL, Mansfield JP, Maratos-Flier E (2005) Neuropeptides, including neuropeptide Y and melanocortins, mediate lipolysis in murine adipocytes. Obes Res 13: 653–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imbernon M, Beiroa D, Vazquez MJ, Morgan DA, Veyrat-Durebex C, et al.. (2012) Central Melanin-Concentrating Hormone Influences Liver and Adipose Metabolism Via Specific Hypothalamic Nuclei and Efferent Autonomic/JNK1 Pathways. Gastroenterology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28. Jeninga EH, van Beekum O, van Dijk AD, Hamers N, Hendriks-Stegeman BI, et al. (2007) Impaired peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma function through mutation of a conserved salt bridge (R425C) in familial partial lipodystrophy. Mol Endocrinol 21: 1049–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Beekum O, Brenkman AB, Grontved L, Hamers N, van den Broek NJ, et al. (2008) The adipogenic acetyltransferase Tip60 targets activation function 1 of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Endocrinology 149: 1840–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brito MN, Brito NA, Baro DJ, Song CK, Bartness TJ (2007) Differential activation of the sympathetic innervation of adipose tissues by melanocortin receptor stimulation. Endocrinology 148: 5339–5347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spector S, Sjoerdsma A, Udenfriend S (1965) Blockade of Endogenous Norepinephrine Synthesis by Alpha-Methyl-Tyrosine, an Inhibitor of Tyrosine Hydroxylase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 147: 86–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hunt CR, Ro JH, Dobson DE, Min HY, Spiegelman BM (1986) Adipocyte P2 gene: developmental expression and homology of 5′-flanking sequences among fat cell-specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83: 3786–3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang J, Yuan C, Wei L, Yi F, Song F (2009) Melanin-concentrating hormone receptor 2 affects 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation. Mol Cell Endocrinol 311: 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hill J, Duckworth M, Murdock P, Rennie G, Sabido-David C, et al. (2001) Molecular cloning and functional characterization of MCH2, a novel human MCH receptor. J Biol Chem 276: 20125–20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mul JD, la Fleur SE, Toonen PW, Afrasiab-Middelman A, Binnekade R, et al. (2011) Chronic loss of melanin-concentrating hormone affects motivational aspects of feeding in the rat. PLoS One 6: e19600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guesdon B, Paradis E, Samson P, Richard D (2009) Effects of intracerebroventricular and intra-accumbens melanin-concentrating hormone agonism on food intake and energy expenditure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bartness TJ, Song CK (2007) Thematic review series: adipocyte biology. Sympathetic and sensory innervation of white adipose tissue. J Lipid Res 48: 1655–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Onai T, Kilroy G, York DA, Bray GA (1995) Regulation of beta 3-adrenergic receptor mRNA by sympathetic nerves and glucocorticoids in BAT of Zucker obese rats. Am J Physiol 269: R519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Handlon AL, Zhou H (2006) Melanin-concentrating hormone-1 receptor antagonists for the treatment of obesity. J Med Chem 49: 4017–4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]