Abstract

The skin as the outmost epithelial tissue is under frequent physical, chemical and biological assaults. To counter the assaults and maintain the local tissue homeostasis, the skin is stationed with various innate or innate-like lymphocytes such as γδT cells. Increasing evidence suggest that an intrathymically programmed process is involved in coordinated expression of multiple homing molecules on specific γδT cell subsets to direct their localization in different regions of the skin for the protective functions. However, detailed molecular events underlying the programmed skin distribution of specific γδT cell subsets are not fully understood. We report herein that the temporally and spatially regulated downregulation of chemokine receptor CCR6 on fetal thymic Vγ3+ epidermal γδT precursors is involved in their thymic egress and proper localization in the epidermis. Failure of downregulation of CCR6 in the mature Vγ3+ epidermal γδT precursor cells due to the constitutive expression of transgenic CCR6 resulted in their abnormal accumulation in the fetal thymus and reduced numbers of the epidermal γδT cells. In addition, the transgenic expression of CCR6 on the Vγ3+ γδT cells also improperly increased their distribution in dermis of the skin. Those findings advanced our understanding of the molecular basis regulating the tissue specific distribution of various innate-like γδT cell lymphocytes in the skin.

Introduction

Unlike conventional αβ T cells, various subsets of γδ T cells display the properties of innate immune cells. Many of these innate-like γδT cells preferentially reside in epithelial tissues covering the external and internal surface of the body, such as the skin, reproductive tracts and lungs where they function as the first line of defense (1). However, the mechanisms that direct the preferential localization of the innate-like γδT cells in the epithelial tissues are not well understood.

γδ T cells in the skin of mice include some of the most representative epithelial tissue-resident innate-like γδT cells. In the epidermis, nearly all the resident γδT cells [referred to as skin intraepithelial γδ T lymphocytes (sIEL) or dendritic epidermal T cells (DETC)] express canonical Vγ3/Vδ1+γδ T cell receptors (TCR) (2). The Vγ3+ sIELs could recognize and be activated by (unidentified) skin-specific antigen(s) induced by the local patho-physiological changes (3). The activated Vγ3+ sIELs have the cytolytic capacity to kill skin tumor cells and are able to express an array of cytokines and factors such as IFN-γ, insulin-like factor 2 and keratinocyte growth factor that mediate functions of the sIELs in immune surveillance against cutaneous tumors (4–7), regulation of local inflammatory responses (8–10) and wound healing (3, 11, 12). In the dermis, the γδT cell repertoire is more diverse than that of epidermal γδT cells based on their γδTCR usage. A significant fraction of the dermalγδT cells, many of whom express the Vγ2+ TCR, are the dominant source of IL-17 (therefore referred as γδT17 cells) during the early innate phase of immune response against the bacterial infection but also involved in the skin inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis (13–16). Functionally similar subsets of γδ T cells are also found in the epidermis and dermis of humans (although they use different γδTCRs than the murine γδT cells)(13, 17–20), suggesting evolutionarily conserved development of the skin-resident γδT innate-like lymphocytes of unique functional capacities to protect the local tissue integrity.

We previously reported that the fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells, which are exclusive precursors for the Vγ3+ epidermal sIELs, are programmed in the thymus for their specific distribution into the epidermis (21, 22). The fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors underwent a positive selection-dependent process that results in a coordinate switch in the expression of homing molecules and cytokine receptors that are known or potentially important for their migration and maintenance in (to) the skin (21–23). Particularly, upregulation of chemokine receptor CCR10, integrin CD103, adhesion molecules E-selectin ligand and p-selection ligand on the positively selected fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors is important for their localization into epidermis (23–25), while the upregulation of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1) is likely important for the thymic egress of the mature Vγ3+ sIEL precursor cells (21, 26). In addition, the upregulation of cytokine receptor CD122 (IL-2 receptorβ chain) on the positively selected fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors is critical for their survival/proliferation in the skin and mice deficient of CD122 or its ligand IL-15 do not have the epidermal γδT cells (15, 27–29). The dermal γδT17 cells are recently found also predominantly originating from the fetal thymic γδT cells (14, 30). Although mechanisms regulating localization of the fetal thymic precursors of theγδT17 cells in the dermis are not well studied, the dermal γδT17 cells express different (although overlapping) sets of chemokine receptors and adhesion molecules than the epidermal γδT cells and it is likely that localization and maintenance of the different subsets of γδT cells into the different regions of the skin are differentially coordinated during their fetal thymic development stage (14, 15).

The programming of Vγ3+ sIEL precursors in the fetal thymus is not only associated with upregulation of the homing molecules and cytokine receptors important for their location and survival in the skin but also downregulation of other molecules such as chemokine receptor CCR6 (21, 31). Since the ligand for CCR6, CCL20, is expressed in the thymus (32, 33), the downregulation of CCR6 might be a part of the regulation process that allows for the egress of mature fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors from the thymus (21). In addition, considering that the dermal γδT cells express CCR6, the regulated downregulation of CCR6 on the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors might be also involved in their distribution into the epidermal but not dermal regions of the skin. To address these questions, we generated a strain of CCR6 transgenic mice that maintain a constitutive expression of CCR6 on the mature sIEL precursors and sIELs. Using the CCR6 transgenic mice, we show that the programmed downregulation of CCR6 on the mature fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors is involved in regulation of their thymic egress as well as proper distribution in the epidermis of the skin.

Materials and Methods

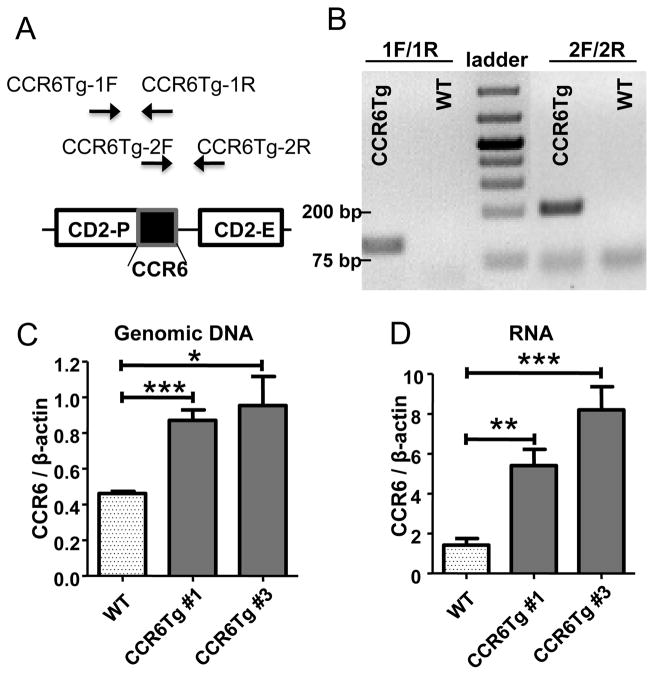

CCR6 transgenic mice

To generate CCR6 transgenic (CCR6Tg) mice, a DNA fragment containing the coding sequence of mouse CCR6 was inserted into a transgenic expression vector under the control of the human CD2 promoter (CD2-P) and enhancer (CD2-E) (Fig. 1A)(34). The CCR6 transgenic vector was injected into fertilized eggs of C57BL/6 (B6) mice (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) to generate transgenic founders. The CCR6 transgenic founders were crossed with B6 mice and two lines of germline-transmitted CCR6 transgenic mice were obtained, as identified by PCR using primers specific for the transgenic (but not endogenous) CCR6 sequences (The primers CCR6Tg-1F and CCR6Tg-1R that span the start codon of transgenic CCR6 and primers CCR6Tg-2F and CCR6Tg-2R that span the stop codon of transgenic CCR6) (Fig. 1A and B). To determine copy numbers of the CCR6 transgenes, genomic DNA of the transgenic mice were subject to a real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis with primers CCR6-2F and CCR6-2R that amplify both endogenous and transgenic CCR6 genes and copy numbers of the CCR6 transgenes were calculated by comparing normalized results of the qPCR for CCR6 of the transgenic CCR6 mice with those of wild type (WT) mice, which have two copies of the endogenous CCR6 gene. Based on the qPCR analysis, we calculated that both lines of the transgenic mice have two copies of CCR6 transgenes (Fig. 1C). The real-time RT-PCR analysis of mRNA from splenic T cells found that transcript levels of total CCR6 (of both endogenous and transgenic CCR6 genes) are higher in transgenic CCR6 mice than WT controls (Fig. 1D). The transcript level of CCR6 in one line of the transgenic mice (#3) is also higher than another line (#1) (Fig. 1D), likely due to the position effect of transgene integration into the genome. To identify CCR10-expressing cells, the CCR6 transgenic mice (line #3) were also crossed to the CCR10-EGFP reporter mice in which the coding sequence of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) replaced a coding region of CCR10 from the endogenous CCR10 locus so that the expression of CCR10 could be reported by the knocked-in EGFP (23). All the animal experiments were approved by Pennsylvania State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Figure 1.

Generation of CCR6 transgenic mice. A. The construct of the CCR6 transgenic vector and positions of PCR primers used in identification of the CCR6 transgene. B. Identification of transgenic CCR6 mice by PCR with two pairs of primers specific to the transgenic CCR6 sequence as shown the panel A. C. The real-time quantitative PCR analysis to determine copy numbers of CCR6 transgenes. Genomic DNA isolated from CCR6 transgenic and wild type mice were subject to the PCR analysis with a pair of primers within the common region of transgenic and endogenous CCR6 genes. D. The real-time RT-PCR analysis for the increased CCR6 transcripts in splenic T cells of CCR6 transgenic mice. The results are averages of three to five mice of each genotype. NS: no significant difference; * p< 0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 (applied to all figures).

Primer sequences and PCR

Primer sequences are: CCR6Tg-1F: 5′GGACTCCACCAGTCTCACTTC; CCR6Tg-1R: 5′GTTGTCATAATCATCCGTTCCAA; CCR6Tg-2F: 5′ TGAAGGATGTGTGGTGTATGAGA; CCR6Tg-2R: 5′CTGTCTAGGGTGAATGGTGAAC; CCR6-2F: 5′AACACTGACGCACAGTAAG; CCR6-2R: 5′CATAAACAGCAAAGGGGTG; β-actin-F: CCCATCTACGAGGGCTAT; β-actin-R: TGTCACGCACGATTTCC. For the PCR amplification of keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), primers KGF-fp: CGGAATTCATGCCCAAATGGATACTGACACGG and KGF-rp: CGGAATTCTTAGGTTATTGCCATAGGAAG were used. Quantitative PCR was performed using the SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA)

Antibodies and reagents

PE/Cy7-anti-CD24 (clone M1/69), Alexa Fluor 647-anti-IL17A (clone TC11-18H10.1), APC-anti-Vγ2 (UC3-10A6), Alexa Fluor 647-anti-CD3 (clone 17A2) and PE-anti-Vγ3 (clone 536) antibodies were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). FITC-anti-Vγ3 (clone 536) antibody and PE-Texas Red streptavidin were from BD Bioscience (San Diego, CA). Biotin-anti-CD122 (clone TM-b1) and PE/Cy5-anti-CD44 (clone IM7) were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Purified anti-mCCR6 (Clone 140706) was from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN). FITC-goat anti-Rat IgG + IgM and Biotin-goat anti-Rat IgG were from Jackson ImmunoReaserch (West Grove, PA). CCL20 was from Pepro Tech (Rocky Hill, NJ). PE-streptavidin and Dispase were from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Anti-Vγ1.1 and 17D1 antibodies are gifts of Drs. Pablo Pereira (Pasteur Institute, Paris) and Robert Tigelaar (Yale University). Collagenase was from Worthington Biochemical (Lakewood, NJ). Hyaluronidase was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Mounting medium with DAPI was from Vector Labs (Burlingame, CA).

Cell preparation

Thymocytes were isolated as described (21). To isolate lymphocytes from epidermis and dermis of the skin, the dorsal and ventral skins were first treated with 20mM EDTA (for newborn mice) or with 1 mg/ml dispase (for adult mice) to separate the epidermis and dermis. The epidermis and dermis were then minced and digested with collagenase and hyaluronidase for 1–2 hours with gentle shaking to dissociate cells (35). Mononucleocytes were enriched from the cell preparations using Percoll gradients (40%/80%) and used for flow cytometric analysis.

Cellular staining and flow cytometry

Cells were incubated with fluorescently labelled antibodies for 30 min at 4°C and analyzed on the flow cytometer FC500 (Beckman Counter, Miami, FL). For the CCR6 staining, cells were incubated with purified anti-mCCR6 (R&D systems) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with Biotin-conjugated goat-anti-rat IgG for 60 min at room temperature. The cells were then stained with PE-streptavidin for 15 min at room temperature and analyzed by flow cytometry. Intracellular staining for IL-17A was performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction (eBioscience). Staining with 17D1 for Vγ4+ cells were performed as previously described (36). Data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Cell sorting

The embryonic day 17 (E17) fetal thymocytes of CCR10+/EGFP mice and CCR10+/EGFPCCR6Tg mice were stained and sorted for EGFP+ and EGFP− Vγ3+CD3+ cells on an Influx sorter (Cytopeia, Inc. San Jose, CA). E17 fetal thymocytes of wild type mice and CCR6Tg mice were stained and sorted for CD122+ and CD122− Vγ3+CD3+ cells. CD3+ splenocytes were purified by the sorter from splenocyte preparations based on the CD3 expression. Epidermal and dermal lymphocytes of wild type mice and CCR6Tg mice were stained and sorted for Vγ3+CD3+ and Vγ3−CD3+ cells. Purities of the sorted populations were at least 95%.

Immunofluorescent microscopy of epidermal sheets

The experiment was performed similarly as previously described (37). The epidermal sheets were peeled from the ear skin of adult mice or the back skin of 7 day-old newborns after the skins were incubated in a 20 mM EDTA/PBS solution for one hour. The epidermal sheets were fixed with acetone, and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-Vγ3 and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-CD3 antibodies overnight and analyzed on a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX61 or Nikon Eclipse TE300). Of one stained ear skin sheet, 5 fields (at 20x amplification) were randomly pictured in each of four sides and one in the middle. Total numbers of sIELs were then enumerated of the five fields and the average number of sIELs per field was calculated.

In vitro chemotaxis assay

The experiment was performed as previously described (21). Briefly, 5× 105 E17 fetal thymocytes of wild type or CCR6Tg mice suspended in DMEM/10% FBS were placed into the upper chamber of a Transwell plate containing 5 μm pore filters (Costar Corp.) and incubated with CCL20 or medium only in the bottom chamber for 4 hours. Cells migrating into the bottom chamber were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry for Vγ3+ T cells along with other markers.

Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Statistical significance was determined by two-tail student T tests. P < 0.05 is considered significant.

Results

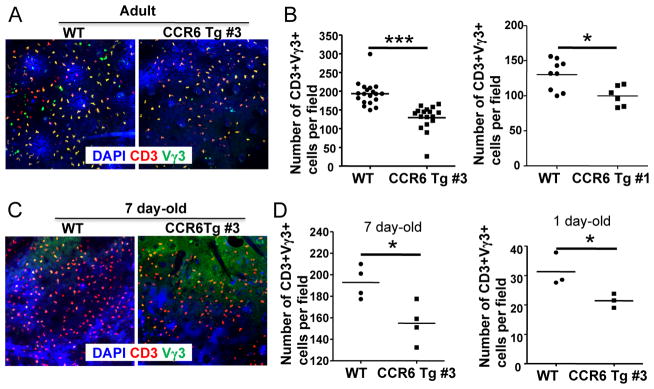

Reduced numbers of Vγ3+γδT cells in epidermis of CCR6 transgenic mice

To determine whether the temporally regulated downregulation of CCR6 on positively selected mature fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors is important for the sIEL development, we compared numbers of sIELs by immunofluorescent microscopy in epidermal sheets of littermates of wild type and CCR6 transgenic mice in which expression of the CCR6 transgene is under control of human CD2 regulatory elements that were previously reported to promote the expression of its regulated gene in mature T cells that express CD2 (34). Comparing to their WT littermate controls, both lines of CCR10 transgenic mice have significantly reduced numbers of Vγ3+ sIELs in the epidermis (Fig. 2A and B). In addition, the higher extent of the percentage reduction of sIELs in the #3 line of transgenic mice than in the #1 line is consistent with the higher transgenic expression level in the former (Fig. 1D).

Figure 2.

Impaired sIEL development in CCR6 transgenic mice. A. Representative Immunofluorescent microscopy of epidermal sheets of adult CCR6 transgenic and wild type mice stained for identification of Vγ3+ sIELs. Epidermal sheets were co-stained with anti-Vγ3 antibody (green), anti-CD3 antibody (red) and counter-stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). The pictures were taken at 20x amplification. B. Quantitative comparison of numbers of Vγ3+ sIELs in adult CCR6 transgenic and wild type mice (at ages of 5–7 weeks). The number of Vγ3+ sIELs is per field (20x amplification) and calculated from enumeration of Vγ3+ sIELs of at least five pictured fields of the immunofluorescent microscopy of one ear epidermal sheet of one mouse. One dot represents the number of Vγ3+ sIELs per field from one mouse. The short flat lines in the middle of dots indicate average numbers of sIELs per field in mice of the different genotypes. C. Representative immunofluorescent microscopy of epidermal sheets of 7 day-old CCR6 transgenic and wild type mice stained for identification of Vγ3+ sIELs as in the panel A. D. Comparison of numbers of Vγ3+ sIELs in 7 day- and 1 day-old CCR6 transgenic and wild type littermates. The number of Vγ3+ sIELs was per field as presented in the panel B.

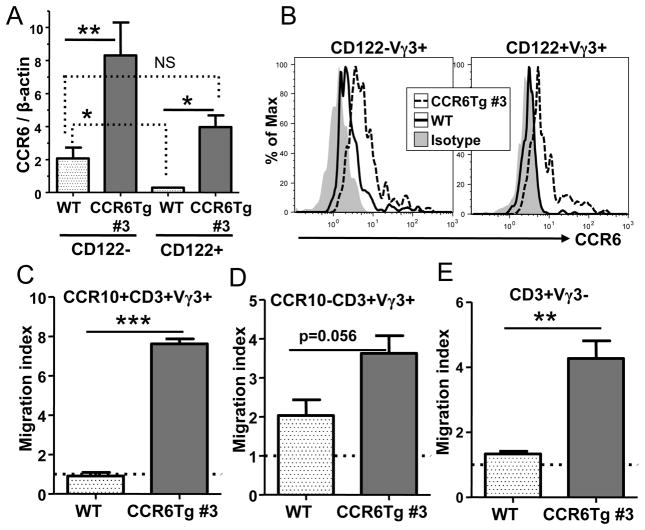

CCR6 transgene predominantly compensates for downregulation of the endogenous CCR6 gene expression in mature Vγ3+ fetal thymic sIEL precursors and alters their response to CCL20

Considering the downregulation of CCR6 is associated with the positively selected mature fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors (21), the impaired sIEL development in the CCR6 transgenic mice suggest that the constitutive expression of CCR6 transgene likely affected the migration and seeding of the mature Vγ3+ sIEL precursors into the skin early in the fetal/neonatal stages. Consistent with this, the impaired development of sIELs in CCR6 transgenic mice was also observed early in the neonatal stage of day 1 and day 7-old mice (Fig. 2C and D). To dissect this further, we then determined how the transgenic CCR6 affects expression of CCR6 in the mature CD122+ and immature CD122− Vγ3+ fetal thymic γδT cell populations and their response to CCL20, the ligand for CCR6.

Based on the real-time RT-PCR analysis for CCR6 transcripts, expression of CCR6 was downregulated in the mature CD122+ Vγ3+ sIEL precursors compared to the immature CD122− Vγ3+ fetal thymocytes in wild type mice (Fig. 3A)(23). The CCR6 expression in CD122+ Vγ3+ fetal thymic sIEL precursors of CCR6 transgenic mice was comparable to that in the immature CD122− Vγ3+ fetal thymic γδT cells of WT littermates (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the CCR6 transgene compensated for downregulation of the endogenous CCR6 expression to result in a constitutive expression of CCR6 in the mature fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors as well as in the immature Vγ3+ cells. The expression of CCR6 in the immature CD122− Vγ3+ fetal thymic γδT cells was also increased in the transgenic CCR6 mice compared to that of the WT littermates (Fig. 3A). Therefore, the upregulated expression of CCR6 in both immature and mature fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells could potentially contribute to the impaired sIEL development.

Figure 3.

Transgenic expression of CCR6 specifically affects response of the mature fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors to CCL20. A. Quantification of expression of the CCR6 transcripts in the CD122- and CD122+ E17 fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells of CCR6 transgenic and wild type littermates by the real-time RT-PCR. Three mice of each genotype were analyzed. B. Flow cytometric analysis of E17 fetal thymic CD122− and CD122+ Vγ3+CD3+ T cells of WT and CCR6Tg mice for the cell surface expression of CCR6. The gray area is of isotype-matched control antibody staining. C and D. In vitro migration analysis of CCR10+ (C) and CCR10− (D) fetal thymic Vγ3+ cells of CCR6 transgenic and wild type mice towards CCL20. The migration index is calculated as a ratio of numbers of Vγ3+ cells migrating into the bottom chamber in presence of CCL20 vs. medium only. The experiments were repeated twice of total six samples. E. In vitro migration analysis of fetal thymic Vγ3−γδT cells of CCR6 transgenic and wild type mice towards CCL20. The experiments were repeated twice of total six samples and performed as in the panels C and D.

Flow cytometric analysis of the surface expression of CCR6 on CD122− and CD122+ fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells of WT and CCR6Tg mice confirmed the findings of the RT-PCR analysis. In WT mice, CD122− fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells expressed low levels of CCR6 while CD122+ fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells did not express CCR6 (Fig. 3B). CCR6 transgene resulted in enhanced expression of CCR6 on both CD122− and CD122+ fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells compared to their respective WT counterparts (Fig. 3B). The cell surface level of CCR6 on CD122+ fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells of CCR6Tg mice was lower than that on their CD122− counterpart of CCR6Tg mice but comparable with that on CD122− fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells of WT mice (Fig. 3B).

The downregulation of endogenous CCR6 expression in the mature CD122+ fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors is associated with the upregulation of CCR10 that is important for the migration of the mature Vγ3+ sIEL precursors to the skin and the CD122+CCR10+ fetal thymic Vγ3+ cells are the fully mature sIEL precursors ready to exit the thymus (22, 23). To determine the stage of the fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL development on which the CCR6 transgene might effect, we crossed CCR6 transgenic mice with CCR10EGFP reporter mice in which expression of CCR10 is reported by the EGFP signal (23). Then we performed an in vitro migration assay to assess how the CCR6 transgene affected responses of the fully mature CD122+CCR10+ and the less mature CCR10− fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors towards CCL20. In contrast to the mature CCR10+ fetal thymic Vγ3+γδ T cells of wild type mice that do not migrate towards CCL20, CCR10+ fetal thymic Vγ3+γδ T cells of CCR6 transgenic mice migrate towards CCL20 efficiently (Fig. 3C). On the other hand, the CCR10− Vγ3+ fetal thymic γδT cells of CCR6 transgenic mice only had a marginal increase in migration towards the CCL20 attraction when compared to the CCR10− fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells of wild type mice (Fig. 3D). Considering that the thymus express CCL20, the predominant effect of CCR6 transgene on the response of the CCR10+ fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors towards CCL20 most likely altered their migration out of the thymus that could contribute to the impaired development of sIELs in CCR6 transgenic mice. The migration of fetal thymic CD3+Vγ3− T cells of CCR6 transgenic mice to CCL20 was also increased compared to that of WT controls (Fig. 3E), suggesting that the CCR6 transgene increased the functional expression of CCR6 on at least some of other mature T cells and could affect their migration from the thymus as well.

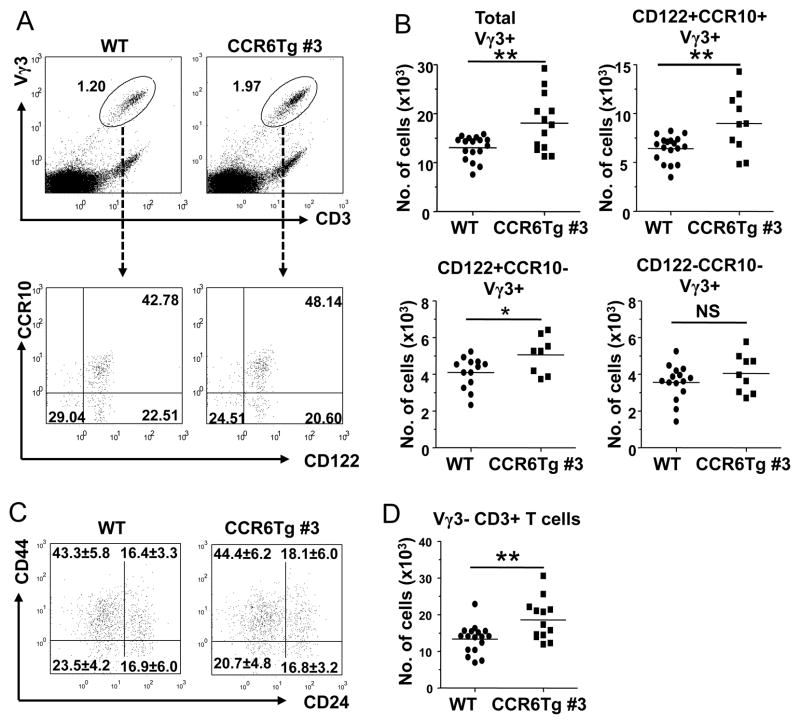

Abnormal accumulation of mature Vγ3+ sIEL precursors correlates with their failed downregulation of CCR6 expression in CCR6 transgenic mice

To determine directly whether the CCR6 transgene specifically affected thymic egress of the mature fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors in vivo, we compared numbers of Vγ3+ fetal thymic γδT cells of the different maturation stages in the CCR6 transgenic and wild type littermates. Compared to the wild type controls, there were increased percentages and numbers of Vγ3+γδT cells in the fetal thymus of CCR6 transgenic mice, suggesting their abnormal accumulation in the fetal thymus and consistent with the impaired thymic egress of the mature Vγ3+ sIEL precursors (Fig. 4A and B). When the total Vγ3+ fetal thymic γδT cells were analyzed further for their maturation status based on the expression of CCR10 and CD122, the relative percentage of the fully mature CD122+CCR10+ population within the Vγ3+γδT cells was higher in CCR6 transgenic mice than in WT mice (Fig. 4A). Based on total numbers of fetal thymocytes and percentages of Vγ3+γδT cells of the different maturation stages within them, we calculated numbers of Vγ3+ fetal thymic γδT cells of the different maturation stages (Fig. 4B). Notably, compared to their respective wild-type controls, the numbers of the fully mature CD122+CCR10+ fetal thymic Vγ3+ cells increased most while the partially mature CD122+CCR10− increased less significantly (Fig. 4B). In contrast, numbers of the immature CD122−CCR10− Vγ3+ fetal thymic γδT cells were not significantly different in CCR6 transgenic and WT mice (Fig. 4B). Together, these results demonstrate that the failure of downregulation of CCR6 in the mature Vγ3+ fetal thymic sIEL precursors results in their impaired egress from the thymus in the CCR6 transgenic mice, which would be likely responsible for the impaired development of sIELs. On the other hand, the CCR10 expression level was similar on CD122+CCR10+ fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells of WT and CCR6Tg mice (Fig. 4A), suggesting that the failed downregulation of CCR6 on the mature sIEL precursors of CCR6Tg mice probably would not affect the CCR10-mediated skin-homing. In addition, the finding that the maturer CD122+ fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT populations were increased while the immature CD122− fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells were not affected in CCR6Tg mice suggests that CCR6 transgene does not affect intrathymic maturation process of the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors. Supporting this notion, fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells of CCR6Tg mice also showed a normal maturation process based on their expression of the maturation marker CD44 and immature marker CD24 (Fig. 4C)(38). The CCR6 transgene resulted in accumulation of other T cells in the fetal thymus (Fig. 4D), consistent with the fact that CCR6 transgene is functionally expressed in T cells other than Vγ3+ fetal thymic γδT cells (Fig. 3E).

Figure 4.

Abnormal accumulation of mature Vγ3+ sIEL precursors in the fetal thymus of CCR6 transgenic mice. A. Flow cytometric analysis of E17 fetal thymocytes for Vγ3+ T cells of CCR6 transgenic and wild type littermates and their expression of CD122 and CCR10 (EGFP). B. Quantitative comparison of numbers of Vγ3+γδT cells of different maturation stages (total, CD122+CCR10+, CD122+CCR10− and CD122−CCR10−) in E17 fetal thymi of CCR6 transgenic and wild type littermates. Numbers of the different Vγ3+γδT cell subsets were calculated from total numbers of fetal thymocytes and the percentages of Vγ3+ fetal thymic γδT cells of different developmental stages as determined in the panel A. One dot represents the number of cells from one mouse. C. Flow cytometric analysis of E17 fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells of WT and CCR6Tg littermates for expression of CD44 and CD24. The cells in the histogram are of the gated Vγ3+CD3+ population. The numbers in each quadrant are average percentage ±standard deviation of cells in the quadrant. At least 9 mice of each genotype were analyzed. D. Quantitative comparison of numbers of E17 fetal thymic Vγ3− T cells in CCR6 transgenic and wild type littermates. The numbers were calculated similarly as in the panel B.

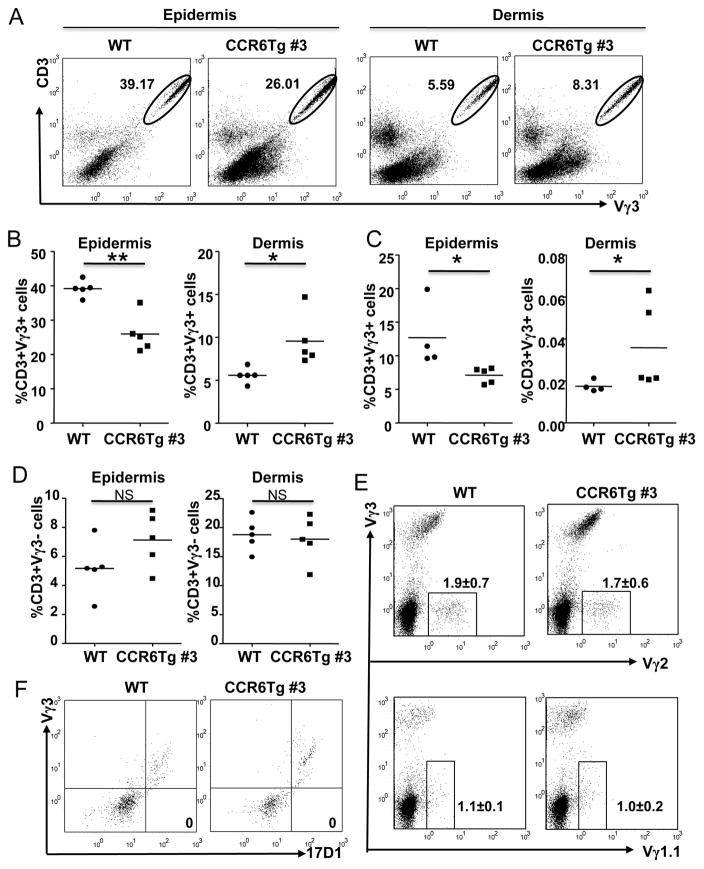

Improper distribution of Vγ3+γδ T cells in dermis of CCR6 transgenic mice

In contrast to the absent expression of CCR6 in the mature fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors and sIELs, all the Vγ3− dermal γδT cells express CCR6 (14, 15). Considering that the CCR6 ligand CCL20 is also expressed in the skin, the differential expression of CCR6 in Vγ3+ sIELs and Vγ3− dermal γδT cells might be involved in their proper localization within the different regions of skin. Therefore, the impaired sIEL development in CCR6 transgenic mice could be also associated with an altered distribution of the Vγ3+γδT cells within the different regions of skin. To test this, we isolated cells from epidermis and dermis of CCR6 transgenic and wild type mice separately and analyzed them for Vγ3+γδT cells by flow cytometry. Confirming that the sIEL development is impaired in the CCR6 transgenic mice, there were significantly lower percentages of Vγ3+ T cells in the epidermis of CCR6 transgenic mice than in wild type controls at both adult and neonatal stages (Fig. 5A–C). In contrast, percentages of Vγ3+γδ T cells in cells isolated from the dermis of CCR6 transgenic mice were much higher than those of the wild type littermates (Fig. 5A–C). As controls, numbers of the total Vγ3−γδT cells and individual subsets of Vγ2+ and Vγ1.1+γδT cells in the dermal region of CCR6 transgenic mice are not different from those of wild type mice, suggesting any additional transgenic CCR6 expression over the endogenous CCR6 expression in the dermal Vγ3−γδT cells did not have impact on their localization in the skin (Fig. 5D and E). In addition, all the dermal 17D1+ cells, which contain both Vγ3+ and Vγ4+ cells (36), stained positive for Vγ3 in both WT and CCR6Tg mice, suggesting that no Vγ4+ cells were in dermis of either WT or CCR6Tg mice (Fig. 5F). These results reveal the specific effect of transgenic CCR6 expression on the localization of Vγ3+γδT cells but not the other γδT cell subsets within the skin. Together, our findings demonstrate that the programmed downregulation of CCR6 in the mature fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors is not only important for their thymic egress but also involved in proper distribution of the Vγ3+ cells within epidermis of the skin.

Figure 5.

Improper distribution of Vγ3+γδ T cells in dermis of CCR6 transgenic mice. A. Representative flow cytometric analysis for Vγ3+ sIELs in cells isolated from epidermis and dermis of adult CCR6 transgenic and wild type mice. The number in the histogram is the percentage of Vγ3+CD3+ T cells of total cells in the histogram. The cells in the histogram are of the “lymphocyte” gate, which is gated in based on the Forward Scatter (FSC) and Side Scatter (SSC) profiles. B–D. Quantitative comparison of percentages of Vγ3+γδT cells in dermis and epidermis of adult WT and CCR6Tg littermates (B) and neonatal WT and CCR6Tg littermates (C), and Vγ3− T cells in epidermis and dermis of adult WT and CCR6Tg littermates (D). One dot represents the percentage of Vγ3+ sIELs from one mouse sample as obtained in the panel A. The short flat lines in the middle of dots indicate average percentage of sIELs in mice of the different genotypes. E. Flow cytometric analysis of cells isolated from dermis of adult WT and CCR6Tg mice for Vγ2+ (top) and Vγ1.1+ (bottom) T cells. The cells in the histogram are gated on CD3+ cells. The number in histogram is the average percentage (±standard deviation) of the gated Vγ2+ or Vγ1.1+ cells of total T cells. Co-staining for Vγ3+ cells is included for comparison of different effects of the CCR6 transgene on Vγ3+ vs. the other γδT cell subsets. N=3 for each genotype. F. Flow cytometric analysis of dermal γδT cells of adult WT and CCR6Tg mice for 17D1+ vs. Vγ3+ staining. The cells in histogram are gated on CD3+TCRδ+ total γδT cell population. The number in the 17D1+Vγ3− quadrant is the percentage of the 17D1+Vγ3− cells of total γδT cell population. N=3 each.

Similar functional capacities of epidermal and dermal Vγ3+γδ T cells in wild type and CCR6 transgenic mice

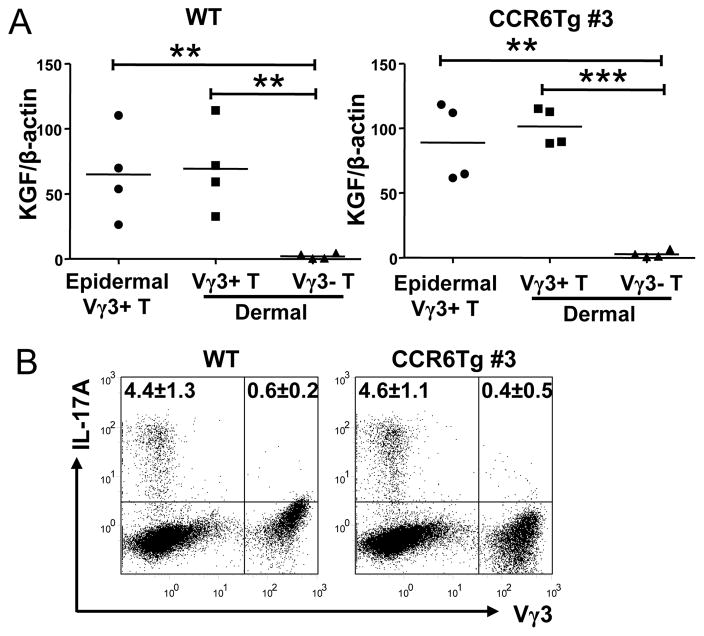

The different localization of Vγ3+γδT cells in epidermis and dermis could potentially affect their functions. We therefore tested whether Vγ3+γδT cells isolated from epidermis and dermis of WT and CCR6Tg mice have different function capacities in production of KGF and IL-17, two factors uniquely associated with epidermal sIELs and dermal γδT17 cells respectively (13–15, 39). As reported, the epidermal Vγ3+γδT cells but not dermal Vγ3−γδT cells of WT mice produce KGF (Fig. 6A). Similar to the epidermal Vγ3+γδT cells, dermal Vγ3+γδT of WT mice also express KGF (Fig. 6A). In addition, the CCR6 transgene had no effect on production of KGF by the epidermal Vγ3+, dermal Vγ3+ and Vγ3−γδT cell subsets (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Comparison of functional capacities of epidermal and dermal Vγ3+γδ T cells of wild type and CCR6 transgenic mice for the production of KGF and IL-17. A. Quantification of expression of the KGF transcripts by the epidermal Vγ3+γδT cells, the dermal Vγ3+γδT cells, and dermal Vγ3−γδT cells of WT and CCR6Tg mice by the real-time RT-PCR. One dot represents the result of one mouse sample. The short flat lines in the middle of dots indicate average levels of all samples of the specific genotypes. B. Flow cytometric analysis of the Vγ3+γδT cells isolated from dermis of WT and CCR6 transgenic mice for the intracellular staining of IL-17. The cells in the histogram are of gated CD3+ cells. The numbers in each quadrant are average percentage ±standard deviation of cells in that quadrant of total CD3+ cells, from analyses of 3 mice of each genotype.

A significant percentage of dermal Vγ3−, but not Vγ3+, T cells express IL-17 in WT mice (Fig. 6B). Vγ3+γδT cells isolated from dermis of CCR6 transgenic mice did not produce IL-17 either (Fig. 6B). In addition, similar percentages of the dermal Vγ3− T cells are capable of producing IL-17 in WT and CCR6Tg mice (Fig. 6B). Therefore, while the CCR6 transgene affects localization of Vγ3+γδT cells within epidermis vs. dermis of the skin, it has no effect on their functional potentials.

Discussion

Since we first reported that a positive selection is required for the developmental distribution of fetal Vγ3+ sIEL precursors in the skin, it has become clear that the intra-thymic γδTCR signalling and the intrinsic property of sIEL precursors are both involved in coordinating expression of an array of chemokine receptors and adhesion molecules on the sIEL precursors for their localization into epidermis (22, 40). On the other hand, whether the TCR signalling is required for maintenance of sIELs in the skin is not completely clear. While some publications suggest that the TCR signalling might be required (41, 42), other existing evidence suggest that the epidermal localization and maintenance of the Vγ3+ sIELs does not require a continuous TCR signalling in the skin (22, 40, 43), supporting the notion that skin-specific distribution of the innate-like γδ T cells is predominantly programmed during their development process in the fetal thymus. Corroborating with the intrathymically programmed tissue-specific distribution of the γδT cells, functional potentials of several innate-likeγδ T cells were recently found to be also pre-programmed in the thymus (44–48), suggesting a coordination during the thymic development of the different subsets of γδT cells that prepare them with specific functional potentials and tissue localizations for their unique roles in protection of the peripheral tissues such as the skin.

To what extent by which the thymic programming controls the tissue-specific location of γδT cells is a critical question in our understanding molecular events regulating the tissue specific distribution of γδT cells in the skin. Previous studies have identified several homing molecules whose expression on Vγ3+ sIEL precursors is programmed during their fetal thymic development stage and is important for the development of sIELs. Particularly, the upregulation of CCR10, CD103, E-selectin ligand and p-selectin ligand is are involved in migration and seeding of the fetal thymus-derived Vγ3+ sIEL precursors into epidermis of the skin (23–25). In addition, the upregulation of S1PR1 on the mature Vγ3+ sIEL precursors is critically important for their egress of the thymus (21, 26)(data not shown). Once in the skin, the expression of homing molecules on the sIELs could be further modulated by the local environment for their maintenance in the skin. For example, while very few fetal thymic sIEL precursors expressed CCR4, nearly all the adult sIELs of the skin express CCR4 that is important for the proper development of sIELs (25). In addition, the expression of CCR10 on the sIELs is downregulated from the level of the fetal thymic sIEL precursors, which is importantly involved in the positioning of the sIELs in the epidermal region of the skin through calibration of the interaction strength of CCR10 of sIELs and its ligand CCL27 expressed by neighbouring keratinocytes (23). Therefore, the spatially and temporally regulated up- and down-regulation of multiple homing and adhesion molecules are involved in both migration into and maintenance of sIELs in the skin. Our finding that the programmed downregulation of CCR6 on the fetal thymic Vγ3+ sIEL precursors is involved in the efficient thymic egress and proper epidermal localization of the Vγ3+ sIELs provide a further support to the notion that the intrathymic programming plays an important role in determining peripheral tissue distribution of specific γδT cell subsets and helps understanding the molecular events mediating the tissue-specific distribution.

Considering that the ligand for CCR6, CCL20, is expressed in the thymus (32, 33), it has been long suggested that the CCR6/CCL20 interaction might be involved in the thymic T cell development. However, up to now, there is no clear evidence that the CCL20/CCR6 pair is involved in the thymic T cell development and CCR6 knockout mice do not have any obvious defect in the conventional T cell development in the thymus. One explanation for this could be that loss of the low level expression of CCR6 on the developing thymic T cells could be functionally compensated for by other chemokine receptors. However, in spite of its low level expression, our study herein suggested that the appropriately regulated expression of CCR6 in thymic Vγ3+γδT cells nevertheless plays an important role in the development of thymic T cells, at least regarding the fetal thymic Vγ3+ cells. Considering that the transgene-driven CCR6 expression in the mature Vγ3+ sIELs is at a comparable level to that of the immature Vγ3+ sIELs (Fig. 3), the transgene-associated phenotypes likely reflect a role of the downregulation of endogenous CCR6 in allowing the efficient thymic egress and proper location of sIELs in the epidermis but are due to significant overexpression of transgenic CCR6 over the level of endogenous CCR6. In this regard, CCR9, another chemokine receptor involved in mediating the entry of early bone marrow progenitor cells into the thymus (49) (50), is also expressed on the immature thymic T cells but downregulated in mature thymic αβ T cells (51). However, in contrast to the CCR6 downregulation reported here, the CCR9 downregulation is not essential for thymocyte export since a transgene-mediated forced expression of CCR9 on mature thymic T cells did not affect numbers of thymic CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (52). In light of our finding, it is possible that the programmed downregulation of CCR9 on thymic mature T cells could be involved in their peripheral localization.

Although the CCR6 downregulation plays a role in the thymic egress of Vγ3+ sIELs, it may not be necessarily a universal mechanism controlling the thymic export of all T cell populations. There were reports that specific mature thymic αβT cell and Vγ2+γδT cell subsets express high levels of CCR6 in adult mice (53)(48). Whether this specific expression of CCR6 is involved in the intrathymic migration and egress is not clear. Considering that all the dermal γδT17 cells express CCR6 and originate from the fetal/peri-natal thymic γδT17 cells (14, 15), it will be interesting to determine whether the fetal thymic precursors of the dermal γδT17 cells express CCR6 and its role in the localization of γδT17 cells in the dermis. Furthermore, since significant numbers of Vγ3+ sIELs were still found in the epidermis of CCR6 transgenic mice, it is apparent that the downregulation of CCR6 on the Vγ3+ sIEL precursors is not absolutely necessary for their thymic export and epidermal localization. This is in contrast with the upregulation of S1PR1, which is critically important for thymic egress of both conventional mature αβT cells as well as γδT cells. Likely, the downregulation of CCR6 is one of multiple molecular events involved in the thymic egress and peripheral tissue localizations of the fetal thymic Vγ3+γδT cells.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank late Thomas Salada for microinjection to generate CCR6transgenic mice.

References

- 1.Hayday AC. [gamma][delta] cells: a right time and a right place for a conserved third way of protection. Annual Review of Immunology. 2000;18:975–1026. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Havran WL, Carbone A, Allison JP. Murine T cells with invariant gamma delta antigen receptors: origin, repertoire, and specificity. Semin Immunol. 1991;3:89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Havran WL. A role for epithelial gammadelta T cells in tissue repair. Immunol Res. 2000;21:63–69. doi: 10.1385/IR:21:2-3:63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girardi M, Oppenheim DE, Steele CR, Lewis JM, Glusac E, Filler R, Hobby P, Sutton B, Tigelaar RE, Hayday AC. Regulation of cutaneous malignancy by gammadelta T cells. Science. 2001;294:605–609. doi: 10.1126/science.1063916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girardi M, Glusac E, Filler RB, Roberts SJ, Propperova I, Lewis J, Tigelaar RE, Hayday AC. The distinct contributions of murine T cell receptor (TCR)gammadelta+ and TCRalphabeta+ T cells to different stages of chemically induced skin cancer. J Exp Med. 2003;198:747–755. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao Y, Yang W, Pan M, Scully E, Girardi M, Augenlicht LH, Craft J, Yin Z. Gamma delta T cells provide an early source of interferon gamma in tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 2003;198:433–442. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strid J, Roberts SJ, Filler RB, Lewis JM, Kwong BY, Schpero W, Kaplan DH, Hayday AC, Girardi M. Acute upregulation of an NKG2D ligand promotes rapid reorganization of a local immune compartment with pleiotropic effects on carcinogenesis. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:146–154. doi: 10.1038/ni1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dieli F, Asherson GL, Sireci G, Dominici R, Gervasi F, Vendetti S, Colizzi V, Salerno A. gamma delta cells involved in contact sensitivity preferentially rearrange the Vgamma3 region and require interleukin-7. European Journal of Immunology. 1997;27:206–214. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weigmann B, Schwing J, Huber H, Ross R, Mossmann H, Knop J, Reske-Kunz AB. Diminished contact hypersensitivity response in IL-4 deficient mice at a late phase of the elicitation reaction. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 1997;45:308–314. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girardi M, Lewis J, Glusac E, Filler RB, Geng L, Hayday AC, Tigelaar RE. Resident skin-specific gammadelta T cells provide local, nonredundant regulation of cutaneous inflammation. J Exp Med. 2002;195:855–867. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharp LL, Jameson JM, Cauvi G, Havran WL. Dendritic epidermal T cells regulate skin homeostasis through local production of insulin-like growth factor 1. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:73–79. doi: 10.1038/ni1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwacha MG. Gammadelta T-cells: potential regulators of the post-burn inflammatory response. Burns. 2009;35:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai Y, Shen X, Ding C, Qi C, Li K, Li X, Jala VR, Zhang HG, Wang T, Zheng J, Yan J. Pivotal role of dermal IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells in skin inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35:596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray EE, Suzuki K, Cyster JG. Cutting edge: Identification of a motile IL-17-producing gammadelta T cell population in the dermis. J Immunol. 2011;186:6091–6095. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sumaria N, Roediger B, Ng LG, Qin J, Pinto R, Cavanagh LL, Shklovskaya E, Fazekas de St Groth B, Triccas JA, Weninger W. Cutaneous immunosurveillance by self-renewing dermal gammadelta T cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:505–518. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pantelyushin S, Haak S, Ingold B, Kulig P, Heppner FL, Navarini AA, Becher B. Rorgammat+ innate lymphocytes and gammadelta T cells initiate psoriasiform plaque formation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2252–2256. doi: 10.1172/JCI61862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebert LM, Meuter S, Moser B. Homing and function of human skin gammadelta T cells and NK cells: relevance for tumor surveillance. J Immunol. 2006;176:4331–4336. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toulon A, Breton L, Taylor KR, Tenenhaus M, Bhavsar D, Lanigan C, Rudolph R, Jameson J, Havran WL. A role for human skin-resident T cells in wound healing. J Exp Med. 2009;206:743–750. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Havran WL, Jameson JM. Epidermal T cells and wound healing. J Immunol. 2010;184:5423–5428. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laggner U, Di Meglio P, Perera GK, Hundhausen C, Lacy KE, Ali N, Smith CH, Hayday AC, Nickoloff BJ, Nestle FO. Identification of a novel proinflammatory human skin-homing Vgamma9Vdelta2 T cell subset with a potential role in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2011;187:2783–2793. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong N, Kang C, Raulet DH. Positive selection of dendritic epidermal γδ T cell precursors in the fetal thymus determines expression of skin-homing receptors. Immunity. 2004;21:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin Y, Xia M, Saylor CM, Narayan K, Kang J, Wiest DL, Wang Y, Xiong N. Cutting edge: Intrinsic programming of thymic gammadeltaT cells for specific peripheral tissue localization. J Immunol. 2010;185:7156–7160. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin Y, Xia M, Sun A, Saylor CM, Xiong N. CCR10 Is Important for the Development of Skin-Specific {gamma}{delta}T Cells by Regulating Their Migration and Location. J Immunol. 2010;185:5723–5731. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schon MP, Schon M, Parker CM, Williams IR. Dendritic epidermal T cells (DETC) are diminished in integrin alphaE(CD103)-deficient mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:190–193. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.17973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang X, Campbell JJ, Kupper TS. Embryonic trafficking of gammadelta T cells to skin is dependent on E/P selectin ligands and CCR4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7443–7448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912943107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, Lesneski MJ, Xu Y, Brinkmann V, Allende ML, Proia RL, Cyster JG. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawai K, Suzuki H, Tomiyama K, Minagawa M, Mak TW, Ohashi PS. Requirement of the IL-2 receptor beta chain for the development of Vgamma3 dendritic epidermal T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:961–965. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Creus A, Van Beneden K, Stevenaert F, Debacker V, Plum J, Leclercq G. Developmental and functional defects of thymic and epidermal V gamma 3 cells in IL-15-deficient and IFN regulatory factor-1-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:6486–6493. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schimpl A, Hünig T, Elbe A. Development and function of the immune system in mice with targeted disruption of the interleukin 2 gene. Academic Press; San Diego: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haas JD, Ravens S, Duber S, Sandrock I, Oberdorfer L, Kashani E, Chennupati V, Fohse L, Naumann R, Weiss S, Krueger A, Forster R, Prinz I. Development of Interleukin-17-Producing gammadelta T Cells Is Restricted to a Functional Embryonic Wave. Immunity. 2012;37:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis JM, Girardi M, Roberts SJ, Barbee SD, Hayday AC, Tigelaar RE. Selection of the cutaneous intraepithelial gammadelta+ T cell repertoire by a thymic stromal determinant. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:843–850. doi: 10.1038/ni1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hieshima K, Imai T, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J, Kusuda J, Tei H, Sakaki Y, Takatsuki K, Miura R, Yoshie O, Nomiyama H. Molecular cloning of a novel human CC chemokine liver and activation-regulated chemokine (LARC) expressed in liver. Chemotactic activity for lymphocytes and gene localization on chromosome 2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5846–5853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varona R, Zaballos A, Gutierrez J, Martin P, Roncal F, Albar JP, Ardavin C, Marquez G. Molecular cloning, functional characterization and mRNA expression analysis of the murine chemokine receptor CCR6 and its specific ligand MIP-3alpha. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:188–194. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01450-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhumabekov T, Corbella P, Tolaini M, Kioussis D. Improved version of a human CD2 minigene based vector for T cell-specific expression in transgenic mice. J Immunol Methods. 1995;185:133–140. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00124-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luci C, Reynders A, Ivanov, Cognet C, Chiche L, Chasson L, Hardwigsen J, Anguiano E, Banchereau J, Chaussabel D, Dalod M, Littman DR, Vivier E, Tomasello E. Influence of the transcription factor RORgammat on the development of NKp46+ cell populations in gut and skin. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:75–82. doi: 10.1038/ni.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roark CL, Aydintug MK, Lewis J, Yin X, Lahn M, Hahn YS, Born WK, Tigelaar RE, O’Brien RL. Subset-specific, uniform activation among V gamma 6/V delta 1+ gamma delta T cells elicited by inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:68–75. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0703326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyauchi S, Hashimoto K. Epidermal Langerhans cells undergo mitosis during the early recovery phase after ultraviolet-B irradiation. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:703–708. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12470379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Beneden K, De Creus A, Stevenaert F, Debacker V, Plum J, Leclercq G. Expression of inhibitory receptors Ly49E and CD94/NKG2 on fetal thymic and adult epidermal TCR V gamma 3 lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2002;168:3295–3302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boismenu R, Havran WL. Modulation of epithelial cell growth by intraepithelial γδ T cells. Science. 1994;266:1253–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.7973709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xia M, Qi Q, Jin Y, Wiest DL, August A, Xiong N. Differential Roles of IL-2-Inducible T Cell Kinase-Mediated TCR Signals in Tissue-Specific Localization and Maintenance of Skin Intraepithelial T Cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:6807–6814. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chodaczek G, Papanna V, Zal MA, Zal T. Body-barrier surveillance by epidermal gammadelta TCRs. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:272–282. doi: 10.1038/ni.2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jameson JM, Cauvi G, Witherden DA, Havran WL. A keratinocyte-responsive gamma delta TCR is necessary for dendritic epidermal T cell activation by damaged keratinocytes and maintenance in the epidermis. J Immunol. 2004;172:3573–3579. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Komori HK, Witherden DA, Kelly R, Sendaydiego K, Jameson JM, Teyton L, Havran WL. Cutting edge: dendritic epidermal gammadelta T cell ligands are rapidly and locally expressed by keratinocytes following cutaneous wounding. J Immunol. 2012;188:2972–2976. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen KD, Su X, Shin S, Li L, Youssef S, Yamasaki S, Steinman L, Saito T, Locksley RM, Davis MM, Baumgarth N, Chien YH. Thymic selection determines gammadelta T cell effector fate: antigen-naive cells make interleukin-17 and antigen-experienced cells make interferon gamma. Immunity. 2008;29:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qi Q, Xia M, Hu J, Hicks E, Iyer A, Xiong N, August A. Enhanced development of CD4+ gammadelta T cells in the absence of Itk results in elevated IgE production. Blood. 2009;114:564–571. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Felices M, Yin CC, Kosaka Y, Kang J, Berg LJ. Tec kinase Itk in gammadeltaT cells is pivotal for controlling IgE production in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8308–8313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808459106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turchinovich G, Hayday AC. Skint-1 identifies a common molecular mechanism for the development of interferon-gamma-secreting versus interleukin-17-secreting gammadelta T cells. Immunity. 2011;35:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Narayan K, Sylvia KE, Malhotra N, Yin CC, Martens G, Vallerskog T, Kornfeld H, Xiong N, Cohen NR, Brenner MB, Berg LJ, Kang J. Intrathymic programming of effector fates in three molecularly distinct gammadelta T cell subtypes. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:511–518. doi: 10.1038/ni.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu C, Saito F, Liu Z, Lei Y, Uehara S, Love P, Lipp M, Kondo S, Manley N, Takahama Y. Coordination between CCR7- and CCR9-mediated chemokine signals in prevascular fetal thymus colonization. Blood. 2006;108:2531–2539. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zlotoff DA, Sambandam A, Logan TD, Bell JJ, Schwarz BA, Bhandoola A. CCR7 and CCR9 together recruit hematopoietic progenitors to the adult thymus. Blood. 2010;115:1897–1905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-237784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Campbell JJ, Pan J, Butcher EC. Cutting edge: developmental switches in chemokine responses during T cell maturation. J Immunol. 1999;163:2353–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uehara S, Hayes SM, Li L, El-Khoury D, Canelles M, Fowlkes BJ, Love PE. Premature expression of chemokine receptor CCR9 impairs T cell development. J Immunol. 2006;176:75–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marks BR, Nowyhed HN, Choi JY, Poholek AC, Odegard JM, Flavell RA, Craft J. Thymic self-reactivity selects natural interleukin 17-producing T cells that can regulate peripheral inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1125–1132. doi: 10.1038/ni.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]