Abstract

Background and Purpose

CT perfusion (CTP) mapping in research centers correlates well with diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) lesions and may accurately differentiate the infarct core from ischemic penumbra. The value of CTP in real-world clinical practice has not been fully established. We investigated the yield of CTP– derived cerebral blood volume (CBV) and mean transient time (MTT) for the detection of cerebral ischemia and ischemic penumbra in a sample of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients.

Methods

We studied 165 patients with initial clinical symptoms suggestive of AIS. All patients had an initial non-contrast head CT, CT Perfusion (CTP), CT angiogram (CTA) and follow up brain MRI. The obtained perfusion images were used for image processing. CBV, MTT and DWI lesion volumes were visually estimated and manually traced. Statistical analysis was done using R-2.14.and SAS 9.1.

Results

All normal DWI sequences had normal CBV and MTT studies (N=89). Seventy-three patients had acute DWI lesions. CBV was abnormal in 23.3% and MTT was abnormal in 42.5% of these patients. There was a high specificity (91.8%)but poor sensitivity (40.0%) for MTT maps predicting positive DWI. Spearman correlation was significant between MTT and DWI lesions (ρ=0.66, p>0.0001) only for abnormal MTT and DWI lesions>0cc. CBV lesions did not correlate with final DWI.

Conclusions

In real-world use, acute imaging with CTP did not predict stroke or DWI lesions with sufficient accuracy. Our findings argue against the use of CTP for screening AIS patients until real-world implementations match the accuracy reported from specialized research centers.

Keywords: Acute ischemic stroke, neuroimaging, Diffusion-Weighted Imaging, stroke diagnosis, ischemic penumbra, perfusion imaging, stroke outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Due to its wide availability, most primary stroke centers use brain non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) as the initial imaging modality for the evaluation of acute stroke patients. Multi-slice CT scanners have the capability to evaluate the intracranial cerebral vasculature and the micro-vascular cerebral perfusion using iodine contrast, usually adding only a few minutes to the head NCCT examination. Current guidelines state that multimodal CT may provide additional information that could improve the diagnosis of ischemic stroke.[1] The use of brain CT perfusion (CTP) improves the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of routinely performed NCCT for the diagnosis of AIS.[2–4] The combination of two CTP parameters: mean transit time (MTT) and cerebral blood volume (CBV), has been suggested to distinguish the infarct core from the ischemic penumbra.[5–7] The CT- CBV hypovolemic lesions are thought to reflect the infarct core in the acute ischemic phase of stroke similar to diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) lesions on brain MRI.[5] Similarly, the CT - MTT has been suggested as surrogate of the ischemic penumbra. The mismatch between CBV and MTT is being studied as a potential target for cerebrovascular reperfusion therapies.[5]

Despite the fact that CTP imaging has not been proven to enhance patient’s outcome in acute brain ischemia, many primary stroke centers are already using CTP images routinely to determine treatments in acute stroke patients within and beyond the 4.5 hours window.[8–10] Most of the CT perfusion studies originate from academic centers, and the value of CTP to predict ischemic core and penumbra and to improve acute diagnoses of stroke has not been validated in a real world setting. In this study we the aim to evaluate the utility of brain CTP imaging for the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke (AIS), prediction of final infarct volume and the estimation the ischemic penumbra.

METHODS

Patients

We evaluated 165 consecutive patients who presented between January 2008 and July 2010 to the Cedars-Sinai Emergency Department (ED) with symptoms suggestive of AIS. All selected patients had an initial Code Brain protocol that included a NCCT, CTP, CT angiogram (CTA), a follow up brain MRI and clinical relevant information in our database. Final discharge diagnosis was obtained in all patients from the hospital medical record and confirmed by the authors. Each patient was classified into one of three groups: ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), or non-stroke. The study was approved by local IRB.

CT and MRI Protocol

The CT stroke protocol was performed with a 64 channels Light speed VCT scanner (GE) and included CT perfusion with 4 cm plane coverage and CT angiography form the aortic arch to the vertex. Parameters were similar to those described by others.[11] CTP image acquisition was performed as a cine series 45 seconds, beginning 5 seconds after 35 to 40 mL of non-ionic iodine contrast injection through a peripheral intravenous catheter (18 to 20 gauge). Follow up MRI was performed on all patients with a 1.5 Tesla Siemens Sonata or Symphony MRI scanner. All MRI studies included b1000, ADC map, and FLAIR sequences.

Imaging Processing

Commercially available software (CT perfusion 3; GE healthcare) was used to calculate parametric maps of CBV and MTT by using baseline CT perfusion data, as described previously.[12] Arterial input and venous output time-attenuation curves were generated, with regions of interest manually drawn by the CT technologist performing the study, usually in the anterior cerebral artery ipsilateral to the side of the infarct and the superior sagittal sinus, respectively. An experienced CT technician generated all perfusion maps and, to reflect everyday practice, maps that were available on a picture archiving and communications system (PACS) were those that were submitted for central review. Post processing of CT angiographic source images reformations was performed by CT technologist and operator console using the manufacturers commercial software. CT angiographic source image reformations were 4 mm thick with a 2 mm gap and were aligned to match the non-contrast CT image.

Evaluation of CTP, CTA and MRI studies

For central review of the images simulating a real-world environment in which the Neurologist will make a treatment decision before final Radiologist interpretation of the images, two Board Certified Vascular Neurologists (WPN, NTB) blinded to the presenting clinical information and final diagnoses interpreted the all the post processed perfusion color map images. Using semiautomatic software (ImageJ v1.42), they visually estimated and manually traced all the CBV, MTT and DWI signals that they believed corresponded to the brain ischemic or hypo-perfused or ischemic areas. Volumes were then calculated using the Cavaleri theorem. Final DWI volume was considered as a surrogate of final infarct. In patients with abnormal DWI, the vascular territory of the infarct was recorded. The CTA was evaluated using the clot burden score (CBS) for clot load and a leptomeningeal collateral scale as previously reported.[13, 14]

Statistical analysis

Group comparisons were performed using Fishers exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum for continuous variables. We dichotomized CBV, MTT and DWI as positive or “abnormal” for volumes >0 ml, and negative or “normal” for volumes equal to zero. Specificity, sensitivity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value areas under the curve, and respective 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each perfusion map and DWI lesion. We used the cube root of total volumes to adjust for variability and to reduce the errors in imaging co-registration. For the estimation of the infarct core, Spearman’s correlation and scatter plots were performed between CTP and MTT cube root volumes against final DWI lesion cube root volume. Independent covariate analysis and logistic regression analysis were performed on CTP maps for predictors of final DWI lesion volume. All analyses were performed with statistical software packages R V2.14.and SAS V9.3.

RESULTS

Of the 165 patients with symptoms suggestive of AIS, 80 had a final diagnosis of stroke, 34 TIA and 51 non – stroke mimics. Baseline characteristics and comparison of the patient groups are shown in Table 1. Nineteen patients had an abnormal CBV color map signal (median volume, [IQR]; 15.2 cc, [9.3–60.1]), 39 patients had an abnormal MTT color map signal (median volume, [IQR]; 53.3 cc, [17–98.6]) and 72 patients had an abnormal DWI hyperintense signal (median volume, [IQR]; 2.3 cc, [0.8–11.8]). For the final diagnoses of stroke we found good specificity but poor sensitivity for both CTP maps. DWI hyperintense lesions had good sensitivity and specificity for ischemic stroke. (Table 2) Utilizing only MCA territorial lesions from CTP and using DWI lesions larger than 5cc as final outcome, the sensitivity and specificity of MTT improved to 81% and 91% whereas for CBV was 62 and 98% respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 165 stroke code patients.

| Stroke N=80 |

TIA N=34 |

Other N=51 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) † | 68.0±14.3 | 67.4±18.2 | 59.7±15.9 | 0.008 |

| Time* from stroke to CTP (med, [IQR])‡ | 194 [113–323] | 152 [110–260] | 166 [113–228] | ns |

| Time* from CTP to MRI (med, IQR)‡ | 1286 [888–2375] | 1266 [915–1518] | 1448 [807–2808] | ns |

| Mean BP mmHg (mean±SD)† | 105.6±18.8 | 106.6±12.8 | 106.2±17.7 | ns |

| NIHSS (med, IQR) ‡ | 4[2–7] | 2[0–3] | 1[0–4] | <0.001 |

| Female n (%)† | 40.5% | 54.6% | 52.9% | ns |

| Hypertension n (%)† | 81.3% | 73.5% | 64% | ns |

| Diabetes n (%)† | 26.3% | 14.7% | 18.0% | ns |

| Dyslipidemia n (%)† | 55.0% | 64.7% | 42.0% | ns |

| Thrombolytic therapy (%)† | 16.3% | 0% | 0% | <0.001 |

IQR: Interquartile range, ns: non-significant

Time in minutes

Fisher’s Exact test.

Kruskal-Wallis test.

Stroke and TIA were not significantly different but both were patients were significantly different than the other diagnoses group.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of CBV, MTT and DWI for final diagnosis of Stroke.

| Sensitivity %(CI) | Specificity %(CI) | PPV %(CI) | NPV %(CI) | AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBV | 20.0 (11.8–30.4) | 96.5 (90.0–99.3) | 84.2 (60.4–96.6) | 55.8 (47.7–64.4) | 58.2% |

| MTT | 40 (29.2–51.5) | 91.8 (83.8 – 96.6) | 82.1 (66.5–92.5) | 61.9 (52.8–70.4) | 65.9% |

| DWI | 77.5 (66.8–86.1) | 88.2 (79.4–94.2) | 86.1 (75.9–93.1) | 80.7 (71.1–88.1) | 82.9% |

CI:95% confidence intervals.

AUC: Area under the curve

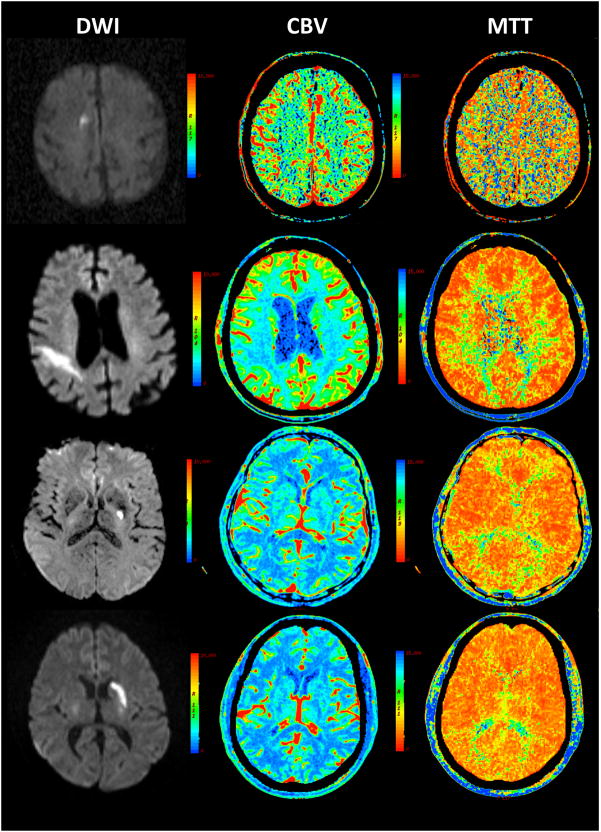

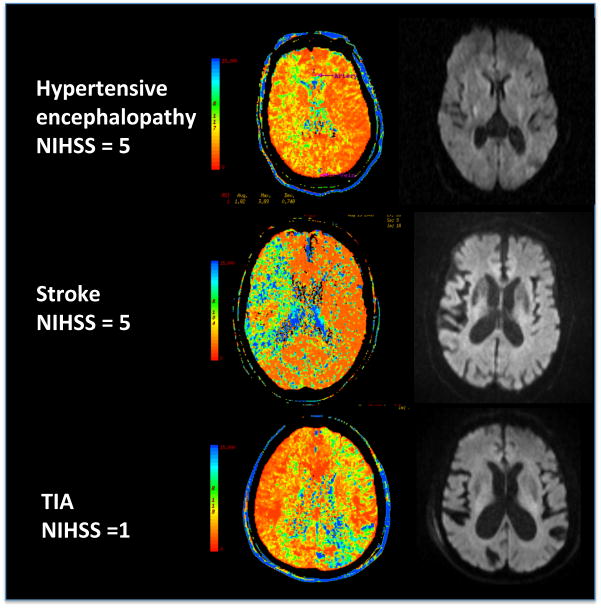

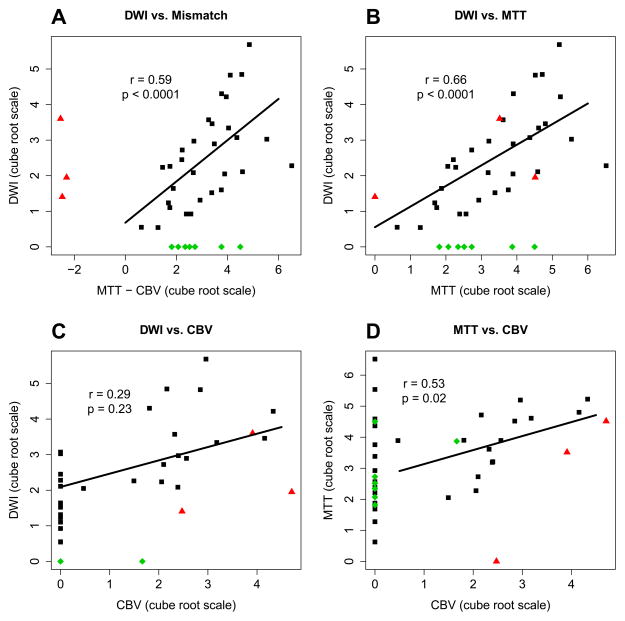

Abnormal MTT was found in 44% of patients with DWI lesions. Examples of non-diagnostic MTT maps with diagnostic DWI lesions are depicted in figure 1. Seven abnormal MTT signals were present in patients with normal DWI scans. (Figure 2) Spearman correlation was significant (ρ= 0.66, p>0.0001) when using only abnormal MTT maps (MTT vol. > 0cc) and abnormal DWI lesions (DWI vol. > 0cc). No significant correlation was found between abnormal CBV maps (CBV vol. > 0cc) and abnormal DWI lesions. (Figure 3) From the stroke patient group with abnormal DWI, lesion volume and MCA territory strokes were independent predictors of an abnormal MTT signal. No other predictors of abnormal CTP perfusion maps were identified. (Table 3 and Figure 4)

Figure 1.

Examples of non-diagnostic CTP studies with abnormal DWI lesions in 4 acute stroke patients

Brain images of 4 different patients are showed in different rows. Right hand column in the right depicts DWI, middle column in the middle CBV and left hand column in the left MTT images. MTT and CBV maps missed the DWI lesions in these 4 patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Figure 2.

Examples of 3 cases of abnormal MTT maps and subsequently normal DWI images.

Figure 3.

Correlation of CPT perfusion maps and DWI volumes.

Black squares represent patients with mismatch present and lesion present in DWI. Green diamonds represents patients with normal DWI. Red triangles represent patients with CBV>MTT. Correlations were calculated using the cube root of the volumes in milliliters using values on both axis >0.

Table 3.

Patients with DWI ischemic lesions divided by normal and abnormal MTT

| Normal MTT | Abnormal MTT | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 40 | N = 32 | ||

| Age (mean±SD)* | 69.9±13.6 | 65.9±15.6 | 0.38 |

| Gender (female%)* | 47.5% | 37.5% | 0.47 |

| Hypertension* | 87.5% | 81.25% | 0.52 |

| Diabetes* | 25.0% | 25% | 1.0 |

| Dyslipidemia* | 57.5% | 56.25% | 1.0 |

| t-PA Reperfusion* | 12.5% | 15.63% | 0.74 |

| NIHSS (mean, IQR) † | 4, [2–7] | 4, [3–9] | 0.46 |

| Mean BP (mean±SD) † | 108.2 ±18.7 | 103.1 ±16.4 | 0.22 |

| Vascular territory (%)* | 0.02 | ||

| ACA | 3(7.5) | 1(3.13) | |

| MCA | 27(67.5) | 30(93.75) | |

| PCA | 7(9.2) | 0(0) | |

| Other | 3(7.5) | 1(3.13) | |

| Time Stroke to CTP (med, IQR) † | 186 [117–301] | 194 [115–378] | 0.93 |

| Time CTP to MRI (med, IQR) † | 1200 [879–1571] | 1657 [1151–2816] | 0.053 |

| DWI lesion volume (med, IQR) † | 1.12 [0.7–2.5] | 11.75 [3.82–39.5] | <0.0001 |

| CBS (med, IQR) † | 10[10-10] | 10[10-9] | 0.59 |

| Leptocollaterals† | 0.44 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 1(3.45%) | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 5(12.82) | 5(17.24) | |

| 3 | 34(87.2) | 23(79.3) |

IQR: Interquartile range, CBS: clot burden score.

Fisher’s exact test.

Exact Matt Whitney test

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that CTP lacked sufficient sensitivity for the diagnosis of AIS. Initial CTP perfusions maps, MTT and CBV, missed more than 50% of clinical strokes that were later identified by brain MRI using DWI sequence. MTT was the best CTP map for the identification of stroke reaching a sensitivity of 40% and specificity of 91.8%. Previous studies have reported sensitivities in the range of 49 to 93% for stroke detection on CTP maps.[2, 15–19] Most of these studies preselected patients with large hemispheric strokes and used DWI as a surrogate for final stroke diagnosis. The lower sensitivity for CTP found in our study could be explained by the inclusion of all vascular territory strokes, the use of the final stroke discharge diagnosis for the definition of stroke and a greater proportion of small ischemic volumes in our sample population. Including small and lacunar strokes also discounts the much lower sensitivity/specificity of CTP. Second, the numbers are further diluted by not using DWI as gold standard. Despite these factors, CBV correlated well in the non-small stroke group. Utilizing DWI as surrogate of stroke outcome, we found The CTP sensitivity and specificity increased to 81% and 91% when we selected MCA territory strokes >5cc and used DWI as surrogate of final stroke. DWI has exquisite sensitivity and specificity for acute stroke diagnosis and constitutes the best surrogate of final brain ischemia.[20] Still, DWI is not infallible; its sensitivity decreases with small stroke lesions[20–22] and in patients with early reperfusion.[23]

Despite the greater sensitivity of CTP for stroke diagnosis with larger DWI ischemic restricted to the MCA territory, most of the large hemispheric strokes do not represent a diagnostic challenge. A simple clinical scale has shown to predict MCA occlusion with high sensitivity and specificity.[24] The sensitivity for the clinical diagnoses of acute stroke in emergency department is estimated to be close to 80% to 90%.[25] A biomarker for stroke diagnosis should then perform better or increase the accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of stroke, and ultimately improve patient outcomes. Our data suggests that CTP has a low probability to diagnose stroke when used as part of an imaging stroke code protocol when all patients suspected to have AIS are included.

We found that lesions located in the MCA territory and large ischemic lesions on DWI predictors of an abnormal CTP maps. Neither the NIHSS nor the combined initial clinical information at the time of stroke evaluation predicted an abnormal CTP study. These findings might argue in favor of using CTP in patients with suspected large MCA territory infarcts. However, the real-world value of the core/penumbra mismatch obtained by CTP in patients with acute stroke is still unclear. In our study we did not find any correlation between CBV and DWI; and therefore failed to support any reliable mismatch between ischemic core and ischemic penumbra. The failure of CBV in detection of the ischemic core and matching the DWI lesions was not completely unexpected. CBV has been shown to be a good surrogate of the ischemic core only in a few studies using large MCA territorial strokes and research-grade post-processing software not available to clinicians.[5, 26, 27]Furthermore, CBV lesions can be reversible and appear to be time dependent.[28] Different CBV thresholds have been suggested for irreversible ischemia, depending on the size of the infarct[5], type of post-processing software[29, 30] or location of the lesion within the white or grey matter.[31] Indeed, there is no agreement yet on definitions and parameters of the ischemic core and penumbra using CTP parameters.[32, 33]

Indicators of ischemic core using other CTP parameters and combinations that may provide a better estimation of the ischemic core are currently under investigation.[30] One reason for the inconsistency of CBV and other CTP parameters may be the use of different software platforms and acquisition times. Recent studies have shown incongruence among different commercial software for the post-processing of raw CTP data for the display of different perfusion maps.[34–36] It also has been suggested that prolonging acquisition time to avoid truncation of time-density tissue curves, which occurs in cases of severe stenosis and hemodynamic disorder scan improve suboptimal perfusion maps.[29]

In our study, abnormal MTT signal was found to be a better predictor of the final DWI lesion. Parsons et al. have shown that CBV correlates better with DWI in patients with vascular reperfusion and MTT does so in patients with no reperfusion.[7] We could speculate that most of our stroke patients did not reperfuse and the penumbral area then converted into the final DWI, but our MTT volumes were consistently larger than the DWI lesions, which is congruent with observations of the penumbra in MCA ischemic strokes, in which the penumbra is usually present and larger than the core.[37]

Multimodal NCCT/CTA/CTP evaluation is not free of risk. Radiation by CT could potentially cause corneal damage, increase the risk of cancer and genetic mutations.[38] Complications from radiation such as rapid hair loss have prompted FDA investigations.[39, 40] Multimodal NCCT/CTA/CTP entails six times the radiation dose compared with NCCT.[41] A subgroup of these patients will subsequently go through catheter base angiographic procedures, which further increases the amount of radiation and iodine contrast exposure. Use of iodine contrast is also linked to contrast induce nephropathy[42] and risk of intracranial hemorrhage due to BBB opening.[43, 44]Furthermore, the processing and interpretation of CTP/CTA studies could potentially delay the time of decision making and treatment in AIS patients leading to worse patient outcomes.[45]

Our study argues against indiscriminate use of CT/CTP/CTA in AIS patients and cautions against its use outside of clinical studies. It has been suggested that CTP could be used to select patients for reperfusion therapies beyond the 3-hour window. Others have found that CTP neither predicts final infarct volume, nor change in neurological function.[46] Moreover, the use of CTP as screening tool to select AIS patients for catheter interventional procedures have not yielded agreement among clinicians.[47]

Several limitations should be noted in our study. Our patients came from a retrospective evaluation of the images from a single primary stroke center. Our sample was quite large compared to previous investigations, but too small to detect confounding variables that could affect the perfusion maps. Few of our patients were treated with thrombolytics and we did not collect the recanalization data that could result in some conversion of MTT to DWI between the initial CTP the MRI imaging.

We used commercial software and the post-processed color map perfusion images for the interpretation and volumetric analysis of the CT perfusion maps; and as discussed before, commercial software has several shortcomings in the post-processing of the CTP maps. Our studies were also done with standard acquisition time. Recently it has been shown that prolonged acquisition time, 60–75 seconds, is required to allow sufficient time for the first-pass wash-in and washout of contrast material resulting in more accurate perfusion maps.[48] Proximal ICA occlusion, severe intracranial stenosis, atrial fibrillation and heart failure are associated with prominent CBF and MTT disturbances that are not necessarily indicative of acute ischemia or associated with stroke. Thus, these patients may be the cause of false-positive CT perfusion results in the unusual situation where the abnormal findings are contralateral to or considered incidental to stroke manifestation. Furthermore, when new hemodynamic or ischemic features arise, these are usually not discernable within the larger region of perfusion abnormality. Finally, the co-registration of CTP slices with DWI for volume calculation was done retrospectively and there was no accounting of sub optimal or completely uninterpretable CTP studies that were entered. However, we believe that most of the limitations of our study are present in majority of primary stroke centers currently using CT perfusion resembling real world practice.

Optimization and standardization of post -processing CTP software and the use of new 128, 256 and 320 slice CT scanners, that promise full brain coverage in non MCA areas, will probably improve the sensitivity of the technique.

The determination of the core and penumbra will require even more complicated postprocessing, similar to the ones done using MRI diffusion and perfusion technologies. Finally, to determine the utility of CT perfusion as a diagnostic and prognostic imaging tool, a prospective study comparing CTP against plain CT with optimal clinical neurological evaluation will be needed.

Conclusions

In real-world acute stroke imaging, CTP was specific but not sensitive for predicting AIS. These data suggest that if acute ischemic lesion detection is paramount, CT may not be a valid surrogate for MR imaging in real-world settings. For the evaluation of the ischemic core and penumbra only in large MCA strokes, MTT lesion volumes correlated well with DWI lesion volumes but CBV did not. Thus, CTP was not useful to obtain a brain ischemic core/penumbra mismatch. Our study supports further study of CTP in real world acute stroke evaluation.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: University of New Mexico Clinical and Translational Science Center, #1UL1RR031977-01

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTIONS: BNH designed he study, acquired the data, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. WPN, BP and NTB acquired data and reviewed the manuscript. RS made the statistical analysis. MM and PDL analyzed the data and reviewed the manuscript.

Disclosures: Authors have nothing to disclose

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Latchaw RE, Alberts MJ, Lev MH, Connors JJ, Harbaugh RE, Higashida RT, et al. Recommendations for imaging of acute ischemic stroke: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40:3646–78. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wintermark M, Fischbein NJ, Smith WS, Ko NU, Quist M, Dillon WP. Accuracy of dynamic perfusion CT with deconvolution in detecting acute hemispheric stroke. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2005;26:104–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wintermark M, Reichhart M, Thiran JP, Maeder P, Chalaron M, Schnyder P, et al. Prognostic accuracy of cerebral blood flow measurement by perfusion computed tomography, at the time of emergency room admission, in acute stroke patients. Annals of neurology. 2002;51:417–32. doi: 10.1002/ana.10136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopyan J, Ciarallo A, Dowlatshahi D, Howard P, John V, Yeung R, et al. Certainty of stroke diagnosis: incremental benefit with CT perfusion over noncontrast CT and CT angiography. Radiology. 2010;255:142–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09091021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wintermark M, Flanders AE, Velthuis B, Meuli R, van Leeuwen M, Goldsher D, et al. Perfusion-CT assessment of infarct core and penumbra: receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in 130 patients suspected of acute hemispheric stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2006;37:979–85. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000209238.61459.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsons MW, Pepper EM, Bateman GA, Wang Y, Levi CR. Identification of the penumbra and infarct core on hyperacute noncontrast and perfusion CT. Neurology. 2007;68:730–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256366.86353.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parsons MW, Pepper EM, Chan V, Siddique S, Rajaratnam S, Bateman GA, et al. Perfusion computed tomography: prediction of final infarct extent and stroke outcome. Annals of neurology. 2005;58:672–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.20638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sztriha LK, Manawadu D, Jarosz J, Keep J, Kalra L. Safety and clinical outcome of thrombolysis in ischaemic stroke using a perfusion CT mismatch between 3 and 6 hours. PloS one. 2011;6:e25796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obach V, Oleaga L, Urra X, Macho J, Amaro S, Capurro S, et al. Multimodal CT-assisted thrombolysis in patients with acute stroke: a cohort study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2011;42:1129–31. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brant-Zawadzki MN, Brown DM, Whitaker LA, Peck WW. Emerging impact of CTA/perfusion CT on acute stroke thrombolysis in a community hospital. Journal of neurointerventional surgery. 2009;1:159–64. doi: 10.1136/jnis.2009.000091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JY, Kim SH, Lee MS, Park SH, Lee SS. Prediction of clinical outcome with baseline and 24-hour perfusion CT in acute middle cerebral artery territory ischemic stroke treated with intravenous recanalization therapy. Neuroradiology. 2008;50:391–6. doi: 10.1007/s00234-007-0358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaefer PW, Barak ER, Kamalian S, Gharai LR, Schwamm L, Gonzalez RG, et al. Quantitative assessment of core/penumbra mismatch in acute stroke: CT and MR perfusion imaging are strongly correlated when sufficient brain volume is imaged. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2008;39:2986–92. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.513358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan IY, Demchuk AM, Hopyan J, Zhang L, Gladstone D, Wong K, et al. CT angiography clot burden score and collateral score: correlation with clinical and radiologic outcomes in acute middle cerebral artery infarct. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2009;30:525–31. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JJ, Fischbein NJ, Lu Y, Pham D, Dillon WP. Regional angiographic grading system for collateral flow: correlation with cerebral infarction in patients with middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2004;35:1340–4. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000126043.83777.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rai AT, Carpenter JS, Peykanu JA, Popovich T, Hobbs GR, Riggs JE. The role of CT perfusion imaging in acute stroke diagnosis: a large single-center experience. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2008;35:287–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin K, Do KG, Ong P, Shapiro M, Babb JS, Siller KA, et al. Perfusion CT improves diagnostic accuracy for hyperacute ischemic stroke in the 3-hour window: study of 100 patients with diffusion MRI confirmation. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28:72–9. doi: 10.1159/000219300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kloska SP, Nabavi DG, Gaus C, Nam EM, Klotz E, Ringelstein EB, et al. Acute stroke assessment with CT: do we need multimodal evaluation? Radiology. 2004;233:79–86. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2331030028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koenig M, Klotz E, Luka B, Venderink DJ, Spittler JF, Heuser L. Perfusion CT of the brain: diagnostic approach for early detection of ischemic stroke. Radiology. 1998;209:85–93. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.1.9769817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayer TE, Hamann GF, Baranczyk J, Rosengarten B, Klotz E, Wiesmann M, et al. Dynamic CT perfusion imaging of acute stroke. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2000;21:1441–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chalela JA, Kidwell CS, Nentwich LM, Luby M, Butman JA, Demchuk AM, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in emergency assessment of patients with suspected acute stroke: a prospective comparison. Lancet. 2007;369:293–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60151-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ay H, Buonanno FS, Rordorf G, Schaefer PW, Schwamm LH, Wu O, et al. Normal diffusion-weighted MRI during stroke-like deficits. Neurology. 1999;52:1784–92. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.9.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sylaja PN, Coutts SB, Krol A, Hill MD, Demchuk AM. When to expect negative diffusion-weighted images in stroke and transient ischemic attack. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2008;39:1898–900. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.497453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.An H, Ford AL, Vo K, Powers WJ, Lee JM, Lin W. Signal evolution and infarction risk for apparent diffusion coefficient lesions in acute ischemic stroke are both time- and perfusion-dependent. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2011;42:1276–81. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.610501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer OC, Dvorak F, du Mesnil de Rochemont R, Lanfermann H, Sitzer M, Neumann-Haefelin T. A simple 3-item stroke scale: comparison with the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale and prediction of middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2005;36:773–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000157591.61322.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldstein LB, Simel DL. Is this patient having a stroke? JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293:2391–402. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.19.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy BD, Fox AJ, Lee DH, Sahlas DJ, Black SE, Hogan MJ, et al. Identification of penumbra and infarct in acute ischemic stroke using computed tomography perfusion-derived blood flow and blood volume measurements. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2006;37:1771–7. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000227243.96808.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pepper EM, Parsons MW, Bateman GA, Levi CR. CT perfusion source images improve identification of early ischaemic change in hyperacute stroke. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2006;13:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knash M, Tsang A, Hameed B, Saini M, Jeerakathil T, Beaulieu C, et al. Low cerebral blood volume is predictive of diffusion restriction only in hyperacute stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2010;41:2795–800. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.590554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaefer PW, Mui K, Kamalian S, Nogueira RG, Gonzalez RG, Lev MH. Avoiding “pseudo-reversibility” of CT-CBV infarct core lesions in acute stroke patients after thrombolytic therapy: the need for algorithmically “delay-corrected” CT perfusion map postprocessing software. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40:2875–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.547679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamalian S, Kamalian S, Konstas AA, Maas MB, Payabvash S, Pomerantz SR, et al. CT Perfusion Mean Transit Time Maps Optimally Distinguish Benign Oligemia from True “At-Risk” Ischemic Penumbra, but Thresholds Vary by Postprocessing Technique. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2011 doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell BC, Christensen S, Levi CR, Desmond PM, Donnan GA, Davis SM, et al. Cerebral blood flow is the optimal CT perfusion parameter for assessing infarct core. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2011;42:3435–40. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.618355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dani KA, Thomas RG, Chappell FM, Shuler K, MacLeod MJ, Muir KW, et al. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance perfusion imaging in ischemic stroke: definitions and thresholds. Annals of neurology. 2011;70:384–401. doi: 10.1002/ana.22500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dani KA, Thomas RG, Chappell FM, Shuler K, Muir KW, Wardlaw JM. Systematic review of perfusion imaging with computed tomography and magnetic resonance in acute ischemic stroke: heterogeneity of acquisition and postprocessing parameters: a translational medicine research collaboration multicentre acute stroke imaging study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43:563–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.629923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kudo K, Sasaki M, Yamada K, Momoshima S, Utsunomiya H, Shirato H, et al. Differences in CT perfusion maps generated by different commercial software: quantitative analysis by using identical source data of acute stroke patients. Radiology. 2010;254:200–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.254082000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamalian S, Kamalian S, Maas MB, Goldmacher GV, Payabvash S, Akbar A, et al. CT cerebral blood flow maps optimally correlate with admission diffusion-weighted imaging in acute stroke but thresholds vary by postprocessing platform. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2011;42:1923–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.610618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zussman BM, Boghosian G, Gorniak RJ, Olszewski ME, Read KM, Siddiqui KM, et al. The relative effect of vendor variability in CT perfusion results: a method comparison study. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2011;197:468–73. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jovin TG, Yonas H, Gebel JM, Kanal E, Chang YF, Grahovac SZ, et al. The cortical ischemic core and not the consistently present penumbra is a determinant of clinical outcome in acute middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2003;34:2426–33. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000091232.81947.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies HE, Wathen CG, Gleeson FV. The risks of radiation exposure related to diagnostic imaging and how to minimise them. BMJ. 2011;342:d947. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wintermark M, Lev MH. FDA investigates the safety of brain perfusion CT. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2010;31:2–3. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith-Bindman R. Is computed tomography safe? The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:1–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1002530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mnyusiwalla A, Aviv RI, Symons SP. Radiation dose from multidetector row CT imaging for acute stroke. Neuroradiology. 2009;51:635–40. doi: 10.1007/s00234-009-0543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.From AM, Bartholmai BJ, Williams AW, Cha SS, McDonald FS. Mortality associated with nephropathy after radiographic contrast exposure. Mayo Clinic proceedings Mayo Clinic. 2008;83:1095–100. doi: 10.4065/83.10.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurosawa Y, Lu A, Khatri P, Carrozzella JA, Clark JF, Khoury J, et al. Intra-arterial iodinated radiographic contrast material injection administration in a rat middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion model: possible effects on intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2010;41:1013–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.578245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khatri P, Broderick JP, Khoury JC, Carrozzella JA, Tomsick TA. Microcatheter contrast injections during intra-arterial thrombolysis may increase intracranial hemorrhage risk. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2008;39:3283–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.522904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta RHA, Wisco D, Tayai AH, et al. CT Perfusion Increases time to reperfusion and may not enhance patient selection for endovascular reperfusion therapies in acute ischemic stroke. Internation Stroke Conference; 2012. p. 207. Oral Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao L, Barlinn K, Bag AK, Kesani M, Cava LF, Balucani C, et al. Computed tomography perfusion prognostic maps do not predict reversible and irreversible neurological dysfunction following reperfusion therapies. International journal of stroke : official journal of the International Stroke Society. 2011;6:544–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hassan AE, Zacharatos H, Chaudhry SA, Suri MF, Rodriguez GJ, Miley JT, et al. Agreement in Endovascular Thrombolysis Patient Selection Based on Interpretation of Presenting CT and CT-P Changes in Ischemic Stroke Patients. Neurocritical care. 2012;16:88–94. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Konstas AA, Goldmakher GV, Lee TY, Lev MH. Theoretic basis and technical implementations of CT perfusion in acute ischemic stroke, part 2: technical implementations. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2009;30:885–92. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]