Abstract

Purpose

To perform a pilot clinical trial of bupropion for methamphetamine abuse/dependence among adolescents

Methods

19 adolescents with methamphetamine abuse (n = 2) or dependence (n = 17) were randomly assigned to bupropion SR 150 mg twice daily or placebo for 8 weeks with outpatient substance abuse counseling.

Results

Bupropion was well tolerated except for one female in the bupropion group who was hospitalized for suicidal ideation during a methamphetamine relapse. Adolescents receiving bupropion and females provided significantly fewer methamphetamine-free urine tests compared to participants receiving placebo (p = 0.043) and males (p = 0.005) respectively.

Conclusions

Results do not support the feasibility of additional trials of bupropion for adolescent methamphetamine abuse/dependence. Future studies should investigate the influence of gender on adolescent methamphetamine abuse and treatment outcomes.

Keywords: methamphetamine, adolescents, female, bupropion, clinical trial

Introduction

While prevalence of methamphetamine use among US high school students (4%) is lower than that for marijuana (37%), methamphetamine abuse in adolescents is associated with serious health consequences including psychiatric symptoms, behavioral problems, risky sexual behavior, pregnancy, and poor cognitive function [1–3]. Effective treatments for adolescent methamphetamine abuse are needed to reduce these negative health consequences, yet few studies have examined treatment of methamphetamine abuse in adolescents. Two studies in methamphetamine dependent adults found bupropion, an anti-depressant and smoking cessation aide, reduced methamphetamine use more than placebo among adults reporting lower frequency of methamphetamine use [4, 5]. We hypothesized that adolescents would have relatively short histories of methamphetamine use and respond to bupropion similarly to adults with lower frequency of methamphetamine use; therefore we performed a pilot clinical trial of bupropion in adolescents with methamphetamine abuse or dependence.

Methods

The study was done at an adolescent outpatient substance abuse treatment program in Los Angeles. Study staff (KH and JG) made presentations and posted fliers about the study at the program and at schools, parks, shopping centers, and youth-oriented community organizations and the study was advertised in local newspapers and websites. Interested adolescents, and their parents if under age 18, met with the study physician (KH) to complete the informed consent process.

Inclusion criteria were: age 14 to 21, DSM-IV methamphetamine abuse or dependence, low frequency of methamphetamine use (use on ≤ 18/30 days), English speaking, if female not pregnant or lactating. Exclusion criteria were: unstable medical condition; major psychiatric disorder not due to substance abuse other than ADHD; past year suicide attempt or current suicidal intention/plan; taking bupropion or medication contra-indicated with bupropion; dependence on cocaine, opiates, alcohol, or benzodiazepines; taking medication for ADHD; seizures or serious head injury; anorexia or bulimia; weight < 50 kg; uncontrolled hypertension; sensitivity to bupropion; any other issue that would compromise participant safety.

Thirty one adolescents consented and 19 were eligible and were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to bupropion 150 mg SR twice daily or matching placebo during outpatient treatment for 8 weeks. Reasons for not being randomized were: withdrew voluntarily (4), failed to complete assessments (2), psychiatric disorder (2), weight < 50 kg (2), alcohol dependent (1), and incarcerated (1). Participants visited the clinic twice a week for 8 weeks for urine drug screens, assessments, medication dispensing/pill counts, and group drug counseling sessions.

Primary outcomes were the feasibility of enrolling participants and the safety and tolerability of bupropion. Exploratory analyses examined treatment retention and Treatment Effectiveness Score (TES, the mean number of twice weekly urine drug screens negative for methamphetamine during 8 weeks of treatment) by treatment group and gender. The study was approved by the UCLA IRB and registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00994448).

Results

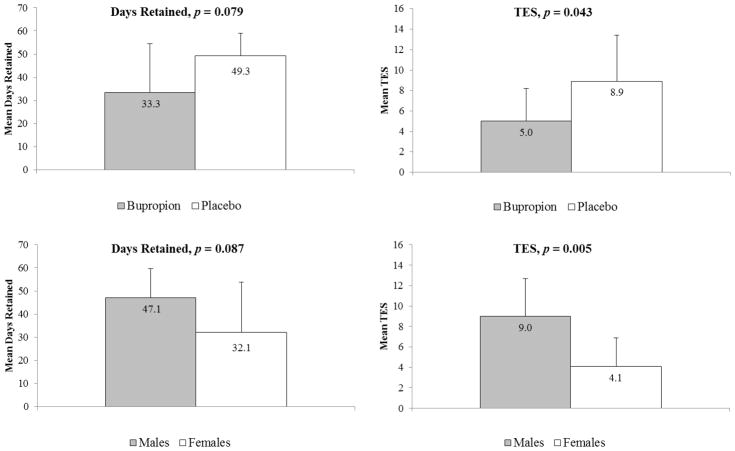

Demographic, substance use, and psychiatric characteristics in the bupropion and placebo groups were similar except for higher pre-treatment methamphetamine cravings in the bupropion group (Table). TES was significantly higher (t = −2.19, d.f. = 17, p = 0.043) in the placebo group relative to the bupropion group (Figure). Retention favored the placebo group but did not reach statistical significance (t = −1.87, d.f. = 17, p = 0.079, Figure). TES was significantly lower in female participants (t = −3.23, d.f. = 17, p = 0.005) and there was a trend for greater retention among males (t = −1.81, d.f. = 17, p = 0.087, Figure). In a linear regression model including treatment group, gender, and pre-treatment methamphetamine cravings, female gender remained significantly associated with lower TES (β = −4.42, t = −2.80, p = 0.013) and treatment condition approached significance (β = −3.13, t = −1.82, p = 0.088).

Figure 1.

Figure Retention and Treatment Effectiveness Score (TES) by treatment condition (top) and gender (bottom) among adolescents with methamphetamine abuse/dependence

Fifty percent (n = 6) of the bupropion group reported at least one adverse event compared to 57% (n = 4) in the placebo group (p = 1.00). Adverse events were mostly minor (flu symptoms, abdominal pain, nasal congestion) except for one serious adverse event, suicidal ideation requiring hospitalization during a methamphetamine relapse among a female participant in the bupropion group. Three participants in the bupropion group (25%) and one in the placebo group (14%) did not return any of the dispensed medication blister packages for pill counts (p = 1.00). The mean proportion of medication taken on available pill counts was similar for bupropion (92%) and placebo (98%, t = −0.87, d.f. = 13, p = 0.40).

Discussion

Results of this study are preliminary due to the small sample size but may guide future research with methamphetamine-using adolescents. We randomized only 19 of a targeted 30 participants despite energetic recruitment suggesting that fully-scaled trials of bupropion in adolescents with methamphetamine abuse are not feasible using this design. Previous studies have also had difficulty enrolling adolescents in substance abuse pharmacotherapy trials [6, 7] suggesting that these challenges are not unique to adolescents with methamphetamine abuse. Specific barriers to enrollment include the multiple exclusion criteria required for pharmacotherapy trials and the outpatient design as severe psychiatric or behavioral problems common in adolescents with methamphetamine abuse typically require inpatient treatment.

The small sample size precludes conclusions concerning the safety or efficacy of bupropion in adolescents with methamphetamine abuse. Bupropion was well tolerated except for one episode of suicidal ideation, a known complication of antidepressants in adolescents, which also may have been triggered by the participant’s methamphetamine relapse [8]. Methamphetamine dependence and cravings, marijuana use, conduct disorder, ADHD, and depressive symptoms were more frequent in the bupropion than placebo group which may explain the poor outcomes observed in the bupropion group.

Females had worse retention and more methamphetamine use during treatment than males. Female adolescents initiate methamphetamine use at a younger age than males and are over-represented among adolescents receiving treatment for methamphetamine abuse [9]. Among adults with methamphetamine dependence, females report more severe baseline methamphetamine use [10] and failed to respond to bupropion [4]. Together, these results suggest that females are more severely impacted by methamphetamine abuse than males in adolescence and into adulthood and highlight the need for additional research into the gender-specific effects of methamphetamine abuse.

Table.

Demographics and pre-treatment substance abuse and psychiatric characteristics by treatment condition among adolescents with methamphetamine abuse/dependence.

| Bupropion (n=12) | Placebo (n=7) | t or χ2 | d.f. | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 17.5 (1.6) | 17.7 (1.1) | −0.308 | 17 | 0.762 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 42% (5) | 57% (4) | N/A 1 | N/A 1 | 0.650 |

| Female | 58% (7) | 43% (3) | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 92% (11) | 86% (6) | 2.315 | 2 | 0.314 |

| White | 8% (1) | 0% (0) | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0% (0) | 14% (1) | |||

| Substance Use Disorders | |||||

| Methamphetamine Dependence | 100% (12) | 71% (5) | N/A 1 | N/A 1 | 0.123 |

| Methamphetamine Abuse | 0% (0) | 29% (2) | N/A 1 | N/A 1 | 0.123 |

| Marijuana Dependence | 67% (8) | 71% (5) | N/A 1 | N/A 1 | 1.000 |

| Marijuana Abuse | 17% (2) | 14% (1) | N/A 1 | N/A 1 | 1.000 |

| Ecstasy Abuse | 33% (4) | 29% (2) | N/A 1 | N/A 1 | 1.000 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 33% (4) | 43% (3) | N/A 1 | N/A 1 | 1.000 |

| Substance Use-days in past 30 | |||||

| Methamphetamine | 4.3 (6.5) | 3.0 (2.9) | 0.48 | 17 | 0.638 |

| Marijuana | 8.7 (10.9) | 5.7 (7.0) | 0.64 | 17 | 0.532 |

| Alcohol | 2.2 (3.6) | 2.1 (4.8) | 0.01 | 17 | 0.990 |

| Tobacco | 5.8 (9.4) | 4.7 (10.0) | 0.23 | 17 | 0.823 |

| Methamphetamine Cravings 2 | 47.2 (32.0) | 12.2 (23.7) | 2.52 | 17 | 0.022 |

| Psychiatric Diagnoses 3 | |||||

| Conduct Disorder | 42% (5) | 29% (2) | N/A 1 | N/A 1 | 0.656 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 25% (3) | 29% (2) | N/A 1 | N/A 1 | 1.000 |

| ADHD | 33% (4) | 0% (0) | N/A 1 | N/A 1 | 0.245 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 17% (2) | 0% (0) | N/A 1 | N/A 1 | 0.509 |

| Social Phobia | 0% (0) | 14% (1) | N/A 1 | N/A 1 | 0.368 |

| CES-D Score 4 | 16.1 (9.3) | 8.6 (6.5) | 1.87 | 17 | 0.078 |

Not applicable due to Fischer’s exact test

Visual Analog Scale, range 0–100

DSM-IV diagnoses as determined via K-SADS

Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale

Implications and Contribution.

Few studies have examined treatment for adolescents with methamphetamine abuse. We performed a pilot trial of bupropion versus placebo for adolescent methamphetamine abuse. Treatment outcomes were worse for bupropion versus placebo and females. Additional studies with bupropion are not warranted but studies into gender and adolescent methamphetamine abuse are needed.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the study was from NIDA grant 5 R21 DA26513 to Dr. Heinzerling. All authors have contributed significantly to this work. Results were previously reported at the 2012 College on Problems of Drug Dependence Annual Meeting.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2011. p. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall BD, Werb D. Health outcomes associated with methamphetamine use among young people: a systematic review. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2010 Jun;105(6):991–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King G, Alicata D, Cloak C, et al. Neuropsychological deficits in adolescent methamphetamine abusers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010 Oct;212(2):243–249. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1949-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elkashef AM, Rawson RA, Anderson AL, et al. Bupropion for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008 Apr;33(5):1162–1170. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shoptaw S, Heinzerling KG, Rotheram-Fuller E, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of bupropion for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008 Aug 1;96(3):222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woody GE, Poole SA, Subramaniam G, et al. Extended vs short-term buprenorphine-naloxone for treatment of opioid-addicted youth: a randomized trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2008 Nov 5;300(17):2003–2011. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray KM, Carpenter MJ, Baker NL, et al. Bupropion SR and contingency management for adolescent smoking cessation. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2011 Jan;40(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auten JD, Matteucci MJ, Gaspary MJ, et al. Psychiatric implications of adolescent methamphetamine exposures. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012 Jan;28(1):26–29. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31823ed6ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzales R, Ang A, McCann MJ, et al. An emerging problem: methamphetamine abuse among treatment seeking youth. Substance abuse : official publication of the Association for Medical Education and Research in Substance Abuse. 2008;29(2):71–80. doi: 10.1080/08897070802093312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinzerling KG, Shoptaw S. Gender, brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met, and frequency of methamphetamine use. Gender Medicine. 2012 Apr;9(2):112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]