Abstract

The complement system is involved in a range of diverse developmental processes including cell survival, growth, differentiation, and regeneration. However, little is known about the role of complement in embryogenesis. Herein we demonstrate a novel role for the canonical complement 5a receptor (C5aR) in the development of the mammalian neural tube under conditions of maternal dietary folic acid deficiency. Specifically, we found C5aR and C5 to be expressed throughout the period of neurulation in wildtype mice and localized the expression to the cephalic regions of the developing neural tube. C5aR was also found to be expressed in the neuroepithelium of early human embryos. Ablation of the C5ar1 gene or the administration of a specific C5aR peptide antagonist to folic acid-deficient pregnant mice resulted in a high prevalence of severe anterior neural tube defect-associated congenital malformations. These findings provide a new and compelling insight into the role of the complement system during mammalian embryonic development.

INTRODUCTION

The complement system is an evolutionarily ancient component of the innate immune system, with its origin dating back 1300 million years (1). The traditional view of complement is that of defence, in which activation of the complement system triggers a protein cascade resulting in the recruitment of immune cells and rapid opsonization and destruction of foreign pathogens. In recent years, there has been increasing evidence that complement is also involved in a diverse range of non-immune processes including cell survival, growth, differentiation, and regeneration (2–5). Furthermore, studies in Xenopus have demonstrated a potential developmental role for complement, with numerous complement factors being expressed in the neural plate during embryogenesis (6).

Formation of the neural plate is the first stage of neurulation, a process where the primitive neural tube is transformed into the embryonic precursors of the central nervous system. Failure of neurulation leads to neural tube defects (NTDs), which can occur at numerous points along the line of neural tube closure. NTDs are a leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide, affecting approximately 1 in 1000 live births (7). It is well established that NTDs have a multifactorial origin, with numerous studies demonstrating contributions from both genetic and environmental factors (8, 9). The most significant finding in the NTD literature to date has been that dietary supplementation with folic acid during the periconceptional period markedly reduces the risk of NTDs (10). However, despite decades of subsequent research, the underlying mechanisms by which folic acid exerts its protective effects have remained elusive.

The aim of the present study was to determine the role of a key component of the complement system, C5a, in neural tube development. C5a is a potent effector of complement that acts predominantly via the G protein-coupled receptor C5aR (also known as CD88). Specifically, we aimed to determine whether C5aR, and the precursor of C5a, C5, were expressed during mammalian neural tube development and, by employing a mouse model of folic acid-deficiency, investigate a putative link between C5aR, folate status, and neural tube development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse models

Folic acid-deficient mouse model

We used a modified version of a previously established folate-deficient mouse model (11). Briefly, female C5ar1+/+ or C5ar1−/− C57BL/6J mice were administered either a folate-replete (1.2 mg folic acid/kg) or folate-deficient diet (<0.1mg folic acid/kg) for a period of six weeks prior to mating. Mice were housed on wire-bottom cages to prevent coprophagy, thus avoiding ingestion of folic acid from the feces (12). The folic acid-deficient diet additionally contained succinylsulfathiazole, an antibiotic that reduces gut flora responsible for the synthesis of folic acid in the mouse gastrointestinal tract.

Timed matings were initiated with 10 to 12 week old virgin females and 8 to 14 week males. Females were inspected daily for the presence of a vaginal plug – designated as 0.5 days post coitum (dpc). A subgroup of C5ar1+/+ mice were administered the potent C5aR antagonist PMX53 (1mg/kg in 100μl of sterile dH2O i.p.) at 4.5 dpc, whereas another subgroup of C5ar1+/+ mice were administered an injection (5% glucose in 100 μl of sterile dH2O i.p.) at 4.5 dpc. Immediately prior to term (18.5 dpc), dams were sacrificed in accordance with the University of Queensland Animal Ethics Committee guidelines and fetuses were harvested, weighed and grossly assessed for overt external congenital malformations. Embryos at 7.5, 8.5, 9.5 and 10.5 dpc were collected in diethylpyrocarbonate -treated PBS and processed for RNA extraction or fixed for histochemistry.

Valproic Acid (VPA) Mouse Model

C5ar1+/+ and C5ar1−/− C57BL/6J mice were housed in conventional cages and administered a folic acid-replete diet throughout both the pre-conceptional and gestational period. Timed matings were initiated with 10 to 12 week old virgin C57BL/6J females and 8 to 14 week males. Females were inspected daily for the presence of a vaginal plug – designated as 0.5 dpc. VPA (600mg/kg, 100 μl, i.p. route) or vehicle treatment (100 μl normal saline, i.p. route) was administered at 8.5 dpc to mice in the VPA treatment group and control group, respectively. Immediately prior to term (18.5 dpc), dams were sacrificed in accordance with the University of Queensland Animal Ethics Committee guidelines and fetuses were harvested, weighed and grossly assessed for overt external congenital malformations.

RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from homogenized embryo tissue using a RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, The Netherlands), followed by DNase treatment with Turbo DNAse (Ambion, USA), and quantified using spectrophotometry. 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using Superscript III (Invitrogen, USA). The following primers were used to amplify gene products with Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs): C5 (forward: 5′-GCTGCTAAGTACAAACATAGTGTGCC -3′; reverse: 5′-GGACAGGTTTATGGGGGCTTTCT -3′); C5ar1 (forward: 5′-GGGATGTTGCAGCCCTTATCA -3′; reverse: 5′-CGCCAGATTCAGAAACCAGATG -3′); Actb (forward: 5′-GTGGGCCGCCCTAGGCACCAG -3′; reverse: 5′-CTCTTTGATGTCACGCACGATTTC -3′).

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as per Christiansen and colleagues (13). Briefly, embryos at 8.5, 9.5 and 10.5 dpc were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.01 M PBS then taken through a dehydration and rehydration series with methanol. Embryos were permeabilized using 10 μg/mL proteinase K, and incubated at 65°C overnight with 0.5 μg of cRNA probe. After removing excess probe, embryos were blocked with 10% goat serum/2% BSA in TBS. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-Digoxigenin-IgG (Roche, Switzerland), pre-adsorbed against embryo antigens, was added in the pre-blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4°C.

For color development, embryos were incubated in 40 μg/mL nitro blue tetrazolium and 20 μg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (Roche, Switzerland). Embryos were taken through an ethanol dehydration series to remove excess color, re-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and imaged using a stereomicroscope (Olympus, Japan).

Immunofluorescence (Mouse)

Embryos at 8.5, 9.5 and 10.5 dpc were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.01 M PBS for 2 hours at 4°C. Embryos were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose prior to embedding in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound. 10 μm sections were obtained for immunofluorescence.

Sections were washed in PBS and pre-blocked in 3% BSA/10% goat serum in PBS. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C: Mouse anti-mouse C5 (clone: BB5.1, 0.5 ug/mL Hycult Biotech, Netherlands), Rat anti-mouse C5aR (clone 10/92, 0.5 μg/mL; Serotec, USA); Rabbit anti-mouse prominin-1 (0.5 μg/mL; Cell Signaling Technology, USA). Primary antibodies were detected using Alexa Fluor 488 Goat anti-Rabbit (1 μg/mL; Invitrogen, Australia) and Alexa Fluor 555 Goat anti-Rat (1 μg/mL; Invitrogen) and 1 μg/ml Alexa Fluor 555 rat anti-mouse. After PBS washes, slides were stained with 0.5 μg/mL 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole in PBS and mounted with ProLong Gold (Invitrogen). Images were captured on a BX61 confocal microscope system (Olympus).

Immunohistochemistry (Human)

Human embryonic material was provided by the Joint MRC/Wellcome Trust Human Developmental Biology Resource (HDBR). HDBR is regulated by the UK Human Tissue Authority and operates in accordance with the relevant Human Tissue Authority Codes of Practice. Samples were obtained with the appropriate maternal written consent and approval from the Newcastle and North Tyneside National Health Service Health Authority Joint Ethics Committee. Embryonic development was determined by examination of external morphological features using the staging protocol for individual embryos based upon the Carnegie staging classifications.

Embryos were fixed overnight at 4°C in 0.1 M PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde and then wax embedded. Following microtomy, sections were de-waxed in xylene and rinsed in absolute ethanol. After preblocking (10% normal sheep serum/TBS), sections were incubated at 4°C overnight with mouse anti-human C5aR antibody (clone W17/1, 1:5 dilution 2% normal sheep serum/TBS; Hycult Biotech), followed by CY3 anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:100 dilution 2% normal sheep serum/TBS; Sigma-Aldrich, Australia). The tissue was counterstained with DAPI (1:10000 TBS; Invitrogen), mounted with Vectorshield (Vector Laboratories, USA) and imaged using an AR1 confocal microscope (Nikon, Japan).

Statistics

The frequency of malformations was calculated as the percentage of defected fetuses out of the total number of viable fetuses. Fetal resorptions were calculated as a percentage of the number of resorptions out of the total number of implantations. Both the frequency of congenital malformations and resorptions was analyzed using chi-square analysis with post-hoc Fischer’s exact tests. Fetal weights, litter sizes, crown-rump lengths and placental weights were plotted as litter means, and compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison test between the wild-type groups. An unpaired student’s t-test was used to compare the C5ar1−/− groups. Significance was set at p < 0.05, where p = n.s. indicates non-significance. Analysis was computed using GraphPad Prism 6 software (Graphpad Software Inc., USA). Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

C5 and C5aR mRNA is expressed during murine neurulation and localized to the developing neuroepithelium

RT-PCR revealed C5ar1 and C5 mRNA to be expressed throughout the period of neurulation (7.5 to 10.5 dpc) in wild-type C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 1 J). To determine tissue localization of both C5ar1 and C5 mRNA during neurulation, whole mount in situ hybridization was employed. At 8.5 dpc (Fig. 1 A–B), C5ar1 was localized predominantly to the neural folds, but not in the neural groove (Fig. 1 B). At 9.5 dpc, as the rostral extremity of the neural tube closes and the forebrain vesicles undergo a dramatic increase in volume, C5ar1 expression became restricted to the cephalic region of the embryo. Specifically, C5ar1 expression was evident throughout the prosencephalon, mesencephalon, and rhombencephalon (Fig. 1 D–E). Expression of C5ar1 was also evident in the sites of the otic and optic vesicles, the embryonic precursors to the ears and eyes, respectively (Fig. 1 D–E). At 10.5 dpc, subsequent to the completion of neural tube closure, C5ar1 continued to be expressed in the telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon, metencephalon, and optic vesicles (Fig. 1 G–H). The mRNA for the precursor ligand for C5aR, C5, was also found to be specifically localised to the developing neural tube throughout the period of neurulation (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Expression and Localization of C5ar1 mRNA.

Whole mount in situ hybridization demonstrating the localization of C5ar1 in murine embryos at 8.5 (A–B), 9.5 (D–E), and 10.5 (G–H) days post coitum (dpc). At 8.5 dpc (A–B), C5ar1 is localized predominantly to the neural folds (arrows, B). At 9.5 dpc and 10.5 dpc, expression is evident throughout the prosencephalon (p), mesencephalon (m), rhombencephalon (r) and within the otic vesicles (o) (D–E, G–H). Sense control embryos are also shown (C, F, I). RT-PCR confirms C5ar1 mRNA expression throughout the period of neurulation (7.5, 8.5, 9.5 and 10.5 dpc: J). Liver was used as a positive control. ActB was used as a housekeeping gene for internal calibration. Representative examples shown (n > 3 per experiment).

Figure 2. Localization of C5 mRNA.

Whole mount in situ hybridization demonstrating the localization of C5 in murine embryos at 8.5 (A–B), 9.5 (D–E), and 10.5 (G–H) days post coitum (dpc). At 8.5 dpc (A–B), C5 is localization predominantly to the neural folds (arrows, B). At 9.5 dpc and 10.5 dpc, expression is evident throughout the prosencephalon (p), mesencephalon (m), rhombencephalon (r) and within the otic vesicles (o) (D–E, G–H). Sense control embryos are also shown (C, F, I). RT-PCR confirms C5 mRNA expression throughout the period of neurulation (7.5, 8.5, 9.5 and 10.5 dpc; J). Liver was used as a positive control. ActB was used as a house-keeping gene for internal calibration. Representative examples shown (n > 3 per experiment).

C5 and C5aR protein is localized to the neuroepithelium of the developing murine neural tube

To determine whether C5aR protein is also expressed during neurulation, immunofluorescent labelling of C5aR was performed on sectioned wild-type C57BL/6J embryos. Sections were co-labelled with prominin-1, a neuroepithelial stem cell marker, and DAPI. C5aR protein was expressed throughout the period of neurulation (Fig. 3A, 3F, 3K). C5aR was expressed in prominin-1 positive cells, confirming its cellular localization to the developing epithelium (Fig. 3). By 10.5 dpc, there was some apparent concentration of C5aR to the apical surface of the neuroepithelium (Fig. 3K). As with the mRNA in situ hybridization studies, C5 protein was expressed during the period of neurulation (Fig. 4A, 4F, 4K). In general, localization of C5 appeared more prominent at the apical surface of the neuroepithelium than throughout the deeper layers. Notably, expression of C5 and C5aR is virtually absent from other embryonic regions at these stages. Taken together, the results demonstrate that C5 and C5aR protein are specifically localized to the neuroepithelium of the developing neural tube during the period of neurulation in the murine embryo.

Figure 3. C5aR is expressed on neuroepithelial cells during neurulation.

Confocal immunofluorescent analysis of sections from the rhombencephalon of 8.5 days post coitum (dpc) (A–E), 9.5 dpc (F–J) and 10.5 dpc (K–O) embryos demonstrates C5aR expression (A, F & K) in the neuroepithelium (NE), as marked by prominin-1 (B, G & L). Nuclear localization is defined by a 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) stain (C, H & M) and the RGB channels are merged (D, I & N) to demonstrate C5aR localization to the prominin-1-positive neuroepithelium. At 10.5 dpc, both prominin-1 and C5aR are predominately restricted to the apical surface of the neuroepithelium. Panels E, J & O are secondary antibody-only controls from subsequent tissue sections. Representative examples shown (n > 3 per experiment).

Figure 4. C5 is expressed on neuroepithelial cells during neurulation.

Confocal immunofluorescent analysis of sections from the rhombencephalon of 8.5 days post coitum (dpc) (A–E), 9.5 dpc (F–J) and 10.5 dpc (K–O) embryos demonstrates C5 expression (A, F & K) in the neuroepithelium (NE) membrane, as marked by prominin-1 (B, G & L). Nuclear localization is defined by a 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) stain (C, H & M) and the RGB channels are merged (D, I & N) to demonstrate C5 expression in neuroepithelial cells. At 10.5 dpc, both prominin-1 and C5 are concentrated to the apical surface of the neuroepithelium. Panels E, J & O are secondary antibody-only controls from subsequent tissue sections. Representative examples shown (n > 3 per experiment).

Expression and localization of C5aR in human embryos

These results in the mouse embryo prompted us to examine the expression of C5aR in very early stage human embryos, to gauge the generalizability of these findings to human development. To determine if C5aR was expressed during human embryogenesis, immunofluorescence was performed on Carnegie Stage 13 human embryos. C5aR protein was found to be consistently expressed (n = 3) throughout the human embryonic neuroepithelium (see representative images, Fig. 5). There was a remarkable degree of similarity in the cellular expression of C5aR between the mouse and human in the developing neuroepithelium (compare Fig. 3A and Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. C5aR is expressed in the neuroepithelium during neurulation in a human embryo.

Confocal immunofluorescent image of a sagittal section from the hindbrain of Carnegie Stage 13 human embryo. Expression of C5aR is concentrated to the neuroepithelium. Representative experiment (n = 3).

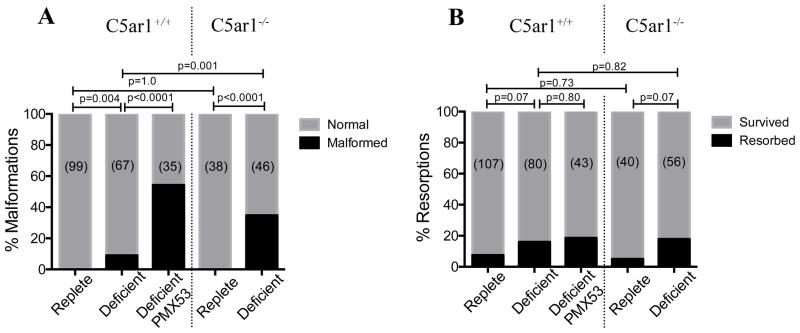

Blockade of C5aR signaling increases the incidence of congenital malformations in a folate-deficient mouse model

Given the highly restricted expression pattern of both C5 and C5aR to the developing neural tube, we next investigated the potential functional role of C5aR in neural tube development. C5ar1−/− mice were found to be fertile and viable with no reported congenital defect phenotypes, consistent with previous reports (14). We additionally found that administration of a specific C5aR peptide antagonist, PMX53 (15, 16), to pregnant wild-type mice resulted in no congenital defects (data not shown), suggesting that inhibition, or genetic absence of C5aR per se, does not affect overt neural tube development.

Given that folate is known to reduce the incidence of NTDs (10), we next investigated whether modulating maternal dietary folate could influence neural tube development. We therefore administered PMX53 to pregnant folate-replete and folate-deficient mice. Remarkably, fetuses from folate-deficient mothers administered PMX53 had a significantly greater incidence of malformations (54.3%) than fetuses from mothers administered a folate-deficient diet alone (8.9%) (P <0.0001; Fischer’s exact test; Fig. 6). Mice administered a folate-replete diet, either with or without PMX53, had none of these congenital malformations.

Figure 6. Blockade of C5aR signaling increases the incidence of congenital malformations in a folate-deficient mouse model.

A. Folate-deficient C5ar1+/+ mice administered PMX53 had a significantly greater incidence of malformed fetuses (53.3%) than folate-deficient C5ar1+/+ mice administered vehicle treatment (8.9%; p < 0.001). Similarly, folate-deficient C5ar1−/− mice had a significantly greater incidence of malformed fetuses (34.8%) than folate-deficient C5ar1+/+ mice (p < 0.001). No folate-replete mice had fetuses with congenital malformations. B. There was no difference in the incidence of fetal resorptions between any of the groups (P = 0.23).

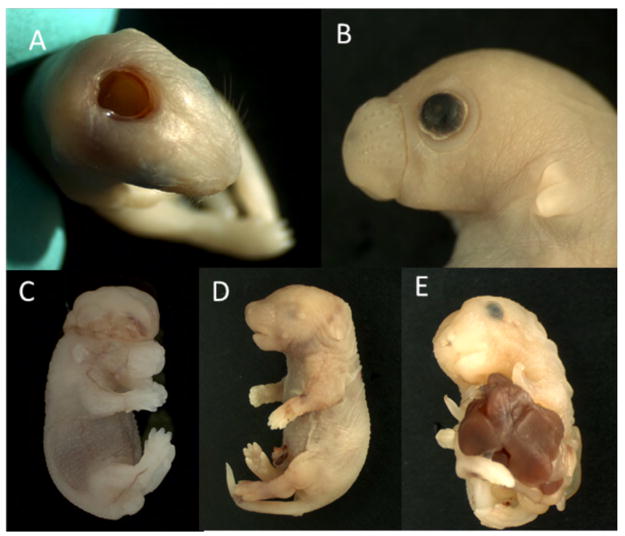

PMX53-treated folate-deficient embryos displayed a diverse range of NTD-associated malformations, including exencephaly (5/35), curly tail (4/35), anencephaly (3/35), as well as microcephaly (3/35), cleft palate (1/35), scoliosis (4/35), and anophthalmia (7/35; Fig. 7).

Figure 7. PMX53-treated folate-deficient embryos display a variety of neural tube defect (NTD)-associated malformations as well as defects in early morphogenesis.

Observed defects included A. Meningoencephalocele, B, Agnathia and ablepharia, C. Exencephaly, D, Microphthalmia, E, Thoracogastroschisis. A and C are NTDs, B, D, E are non-NTDs. Representative samples (n = 6 litters).

To exclude the possibility that PMX53 was exerting an effect independent of its ability to block C5aR, we additionally administered a folate-deficient diet to C5ar1−/− mice. Folate-deficient C5ar1−/− mice had a significantly greater incidence of congenital malformations (34.8%) compared to both folate-replete C5ar1−/− mice (0%) and folate-deficient C5ar+/+ mice (8.9%) (P <0.0001; chi-square test; Fig. 6). There were no significant differences in the incidence of NTD-associated malformations between folate-deficient C5ar1−/− mice and C5ar1+/+ folate-deficient mice treated with PMX53 (P > 0.05; Fischer’s exact test). Folate-deficient C5ar1−/− mice also displayed a similar range of defects to PMX53-treated folate-deficient mice, including exencephaly (n= 9/46), scoliosis (5/46), anophthalmia (1/46), curly tail (6/46), and gastroschisis (6/46). No cardiac defects were observed on dissection of the fetuses.

There were no significant differences in the frequency of fetal resorptions between any of the experimental groups (p = 0.23, ANOVA) (Fig. 6). Similarly, there were no significant differences in litter size, crown-rump lengths between any of the groups (Fig 8. p = 0.68; ANOVA). Folate deficiency resulted in significantly lower fetal weights in both C5ar1+/+ and C5ar1−/− mice; these lower weights were not affected by PMX53 treatment in C5ar1+/+ mice (Fig 8).

Figure 8. Effect of maternal folate deficiency on fetal reproductive parameters.

A. Folate deficiency resulted in significantly lower fetal weights in C5ar1+/+ and C5ar1−/− mice; this was not affected by PMX53 treatment in C5ar1+/+ mice. B. Litter sizes and C, crown-rump lengths were not affected by folate deficiency. D. Placental weights were significantly reduced in C5ar1+/+ mice following PMX53 treatment, but not in any other group.

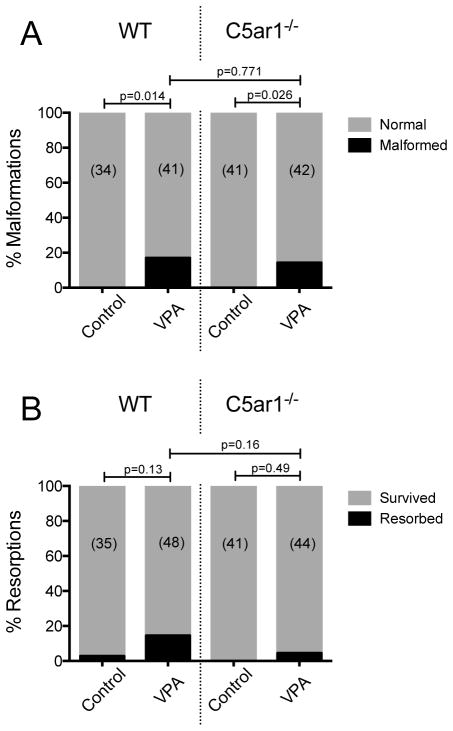

Blockade of C5aR signaling does not reduce the incidence of congenital malformations in the VPA model

In order to determine whether the protective benefit of C5aR extended to other folate-independent models of NTDs, we administered the teratogen VPA to both C5ar1+/+ and C5ar1−/− mice at 8.5 dpc. There were no significant differences in the incidence of VPA-induced congenital malformations between C5ar1+/+ mice (20%) and C5ar1−/− mice (14%; p = 0.45, Fischer’s exact test). No congenital malformations were observed in either C5ar1+/+ or C5ar1−/− mice administered vehicle treatment. The frequency of congenital malformations in the folate-deficient and VPA models are summarised in Figure 9.

Figure 9. C5ar1−/− mice were not resistant to VPA-induced congenital malformations.

There were no significant differences in the incidence of VPA-induced congenital malformations between C5ar1+/+ mice (20%) and C5ar1−/− mice (14%; p = 0.45). No congenital malformations were observed in either C5ar1+/+ or C5ar1−/− mice administered vehicle treatment only.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides the first demonstration that central components of the complement system, namely C5 and C5aR, are expressed during early mammalian development. Specifically, although complement factors have been previously shown to be expressed in developing Xenopus(6), zebrafish (17), and in the postnatal developing rodent brain (18), this is the first study to demonstrate complement factor expression in the early developing murine embryo, and is the first demonstration of complement expression in human embryogenesis.

The expression of C5 and C5aR in the neuroepithelium, the embryonic precursor cells for the developing central nervous system, is suggestive of a potential role for C5a in neurulation. However, and notably, mice lacking the C5aR gene do not display overt congenital anomalies – an observation that has led others to postulate a degree of functional redundancy of developmentally expressed complement proteins (6). The presence of such functional redundancy would be unsurprising given the importance of ensuring that vital developmental processes, including timely neurulation, are preserved. We thus hypothesized that a role for C5aR activation in neurulation may only become apparent under conditions of environmental stress. Given the importance of adequate dietary folate in neurulation (19, 20), we proposed folate-deficiency as a clinically relevant environmental stressor.

In mice, a folate-deficient diet resulted in lower fetal weights, without affecting either litter sizes or placental weights. Blockade of C5a signalling by PMX53 in wild-type mice, or in the genetic knockout mice, did not reverse these lower fetal weights, suggesting that inflammatory processes in the fetus or placenta were not the cause. Girardi and colleagues (22), in a spontaneous murine model of low fetal weights and spontaneous resorptions, demonstrated that this effect could be attributed to C5a-dependent placental inflammation, as maternally administered PMX53 completely reversed these deleterious reproductive outcomes in their model. Conversely, the results presented in this study demonstrate that low fetal weights resulting from maternal dietary folate deficiency are not associated with C5a.

However, prevention of C5aR signaling via the administration of a potent C5aR antagonist, PMX53, to pregnant folate-deficient mice resulted in a significantly greater incidence of a diverse range of fetal malformations than folate-deficiency alone. Folate-replete mice administered PMX53 did not display any fetal abnormalities, which further supports the parallel experiments in C5ar1−/− mice that demonstrated that absence of C5aR signaling alone does not cause overt congenital defects. That pharmacological blockade of C5aR signaling or genetic deletion of C5aR both result in similar quantitative and qualitative NTDs in mice subject to dietary folate stress, suggests an important role for C5aR in neural tube development. In addition, analogous to what was observed in the PMX53 treated mice, folate-deficient C5ar1−/− mice had a significantly greater frequency of malformed offspring than folate-deficient C5ar1+/+ mice – excluding the possibility that PMX53 was exerting an effect independent of its ability to block C5aR.

It has been previously suggested that spontaneous resorption of NTD-affected embryos may be the mechanism underlying the reduction of recognised NTD cases by maternal folate supplementation (21). In addition, C5a has been implicated in miscarriage and fetal growth restriction in both mice and humans (22, 23). However, in the present study, we observed no significant differences in the incidence of spontaneous resorption between any of the experimental groups. Similarly, there were no significant differences in litter size between any of the experimental groups – eliminating the possibility that pharmacological blockade or genetic ablation of C5aR under conditions of folate-deficiency is merely “rescuing” the NTD phenotype via the spontaneous resorption of affected fetuses.

The present study also observed a wide variety of congenital malformations, including exencephaly, curly tail, anencephaly, microcephaly, cleft palate, scoliosis, anophthalmia, and gastroschisis. The diversity of NTDs and related anomalies reflects failure of neural fold elevation and/or fusion in mechanistically distinct zones, as well as defects in early morphogenesis, implying that antagonism of C5aR results from a common underlying mechanism. Significantly, no cardiac defects in any of the experimental groups were observed, indicative of a neuroepithelial, rather than neural crest, etiology – and again consistent with the findings of in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry.

To gain a further insight into the role of C5aR in neural tube closure, the present study also employed a folate-independent model of NTDs, where the teratogen VPA was administered to both C5ar1+/+ and C5ar1−/− mice. Contrary to what was observed in folate-deficient mice, the absence of C5aR had no effect on the incidence of NTDs and related congenital malformations in the VPA model. This result supports the notion that maternal folate-deficiency is necessary to unmask the developmental role of C5aRs. However, elucidating the precise mechanism(s) by which folate and C5aR interact to promote adequate neurulation is a focus for future investigations.

It is now well established that dietary supplementation with folate during the periconceptional period markedly reduces (~70%) the incidence of NTDs in humans (10, 24). However, just how folate exerts its protective effect remains elusive. The present study demonstrates, for the first time, an interaction between dietary folate deficiency and the immune system in the pathogenesis of NTDs, a finding that is of particular interest given that many of the known NTD risk factors, such as maternal diabetes and obesity, have inflammatory features (25). The results are also striking given that C5ar1−/− mice exhibit no NTDs in the presence of adequate dietary folate, which contrasts to other murine models of NTDs in which the protective effect of folic acid supplementation is rarely 100% (26–29). This model thus fulfils many of the criteria required for an archetypal murine model of human NTDs (30); namely the present study reports a relatively low penetrance, non-syndromic model of NTDs that is responsive to nutritional supplementation with folic acid.

We propose that C5a is generated from C5 in the embryo, a thesis supported by the previously established finding that cultured embryonic cells generate their own biologically active C5a from intracellular C5 (31). The finding that C5 and C5aR are both localised to the neuroepithelium in the present study further supports the plausibility of this notion. Finally, the effect of genetic knockout of the post-translational C5a precursor, C5, was not specifically investigated in the present study. We hypothesise that, analogous to what was observed in mice administered PMX53, C5−/− mice administered a folate-deficient diet would similarly have an increased incidence of NTDs due to the inability to produce C5a.

In summary, this study provides the first experimental demonstration of an interaction between folate-deficiency and the immune system in neural tube formation. These results provide a novel paradigm to guide investigation into the causal mechanisms underlying disturbances in mammalian neural tube development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof Rick Wetsel for supplying the C57BL6/J C5ar1−/− knockout mice to establish our colony used in these studies.

The human embryonic material was provided by the Joint MRC (grant # G0700089)/Wellcome Trust (grant # GR082557) Human Developmental Biology Resource. This study was funded through the support of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Project Grant 569693 to SMT, TMW, LKC and RHF), and the Australian Research Council (Future Fellowship FT110100332 to TMW) and a grant (P01 HD067244) from the NIH to RHF.

Non-Standard Abbreviations

- DPC

Days Post Coitum

- NTD

Neural Tube Defect

- VPA

Valproic Acid

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Nonaka M, Kimura A. Genomic view of the evolution of the complement system. Immunogenetics. 2006;58:701–713. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0142-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strey CW, Markiewski M, Mastellos D, Tudoran R, Spruce LA, Greenbaum LE, Lambris JD. The proinflammatory mediators C3a and C5a are essential for liver regeneration. J Exp Med. 2003;198:913–923. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mastellos D, Morikis D, Isaacs SN, Holland MC, Strey CW, Lambris JD. Complement: structure, functions, evolution, and viral molecular mimicry. Immunol Res. 2003;27:367–386. doi: 10.1385/IR:27:2-3:367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reca R, Mastellos D, Majka M, Marquez L, Ratajczak J, Franchini S, Glodek A, Honczarenko M, Spruce LA, Janowska-Wieczorek A, Lambris JD, Ratajczak MZ. Functional receptor for C3a anaphylatoxin is expressed by normal hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, and C3a enhances their homing-related responses to SDF-1. Blood. 2003;101:3784–3793. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavlovski D, Thundyil J, Monk PN, Wetsel RA, Taylor SM, Woodruff TM. Generation of complement component C5a by ischemic neurons promotes neuronal apoptosis. FASEB J. 2012 doi: 10.1096/fj.11-202382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLin VA, Hu CH, Shah R, Jamrich M. Expression of complement components coincides with early patterning and organogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Int J Dev Biol. 2008;52:1123–1133. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072465v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blom HJ, Shaw GM, den Heijer M, Finnell RH. Neural tube defects and folate: case far from closed. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:724–731. doi: 10.1038/nrn1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell LR, Dayton DH, Sohal GS. Neural tube defects: a review of human and animal studies on the etiology of neural tube defects. Teratology. 1986;34:171–187. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420340206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finnell RH, Gelineau-van Waes J, Bennett GD, Barber RC, Wlodarczyk B, Shaw GM, Lammer EJ, Piedrahita JA, Eberwine JH. Genetic basis of susceptibility to environmentally induced neural tube defects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;919:261–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smithells RW, Sheppard S, Schorah CJ. Vitamin dificiencies and neural tube defects. Arch Dis Child. 1976;51:944–950. doi: 10.1136/adc.51.12.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgoon JM, Selhub J, Nadeau M, Sadler TW. Investigation of the effects of folate deficiency on embryonic development through the establishment of a folate deficient mouse model. Teratology. 2002;65:219–227. doi: 10.1002/tera.10040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebino KY, Suwa T, Kuwabara Y, Saito TR, Takahashi KW. Coprophagy in female mice during pregnancy and lactation. Jikken Dobutsu. 1988;37:101–104. doi: 10.1538/expanim1978.37.1_101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christiansen JH, Dennis CL, Wicking CA, Monkley SJ, Wilkinson DG, Wainwright BJ. Murine Wnt-11 and Wnt-12 have temporally and spatially restricted expression patterns during embryonic development. Mechanisms of development. 1995;51:341–350. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kildsgaard J, Hollmann TJ, Matthews KW, Bian K, Murad F, Wetsel RA. Cutting edge: targeted disruption of the C3a receptor gene demonstrates a novel protective anti-inflammatory role for C3a in endotoxin-shock. J Immunol. 2000;165:5406–5409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strachan AJ, Woodruff TM, Haaima G, Fairlie DP, Taylor SM. A new small molecule C5a receptor antagonist inhibits the reverse-passive Arthus reaction and endotoxic shock in rats. J Immunol. 2000;164:6560–6565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woodruff TM, Nandakumar KS, Tedesco F. Inhibiting the C5-C5a receptor axis. Mol Immunol. 2011;48:1631–1642. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carmona-Fontaine C, Theveneau E, Tzekou A, Tada M, Woods M, Page KM, Parsons M, Lambris JD, Mayor R. Complement Fragment C3a Controls Mutual Cell Attraction during Collective Cell Migration. Dev Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevens B, Allen NJ, Vazquez LE, Howell GR, Christopherson KS, Nouri N, Micheva KD, Mehalow AK, Huberman AD, Stafford B, Sher A, Litke AM, Lambris JD, Smith SJ, John SW, Barres BA. The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell. 2007;131:1164–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu H, Kartiko S, Finnell RH. Importance of gene-environment interactions in the etiology of selected birth defects. Clinical genetics. 2009;75:409–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finnell RH, Shaw GM, Lammer EJ, Rosenquist TH. Gene-nutrient interactions: importance of folic acid and vitamin B12 during early embryogenesis. Food and nutrition bulletin. 2008;29:S86–98. doi: 10.1177/15648265080292S112. discussion S99–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hook EB, Czeizel AE. Can terathanasia explain the protective effect of folic-acid supplementation on birth defects? Lancet. 1997;350:513–515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girardi G, Yarilin D, Thurman JM, Holers VM, Salmon JE. Complement activation induces dysregulation of angiogenic factors and causes fetal rejection and growth restriction. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2165–2175. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J, Oh J, Choi E, Park I, Han C, Kim do H, Choi BC, Kim JW, Cho C. Differentially expressed genes implicated in unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:2265–2277. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. Lancet. 1991;338:131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waller DK, Mills JL, Simpson JL, Cunningham GC, Conley MR, Lassman MR, Rhoads GG. Are obese women at higher risk for producing malformed offspring? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:541–548. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greene ND, Copp AJ. Mouse models of neural tube defects: investigating preventive mechanisms. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2005;135C:31–41. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Q, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B. Prenatal folic acid treatment suppresses acrania and meroanencephaly in mice mutant for the Cart1 homeobox gene. Nat Genet. 1996;13:275–283. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleming A, Copp AJ. Embryonic folate metabolism and mouse neural tube defects. Science. 1998;280:2107–2109. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barbera JP, Rodriguez TA, Greene ND, Weninger WJ, Simeone A, Copp AJ, Beddington RS, Dunwoodie S. Folic acid prevents exencephaly in Cited2 deficient mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:283–293. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juriloff DM, Harris MJ. Mouse models for neural tube closure defects. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:993–1000. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavlovski D, Thundyil J, Monk PN, Wetsel RA, Taylor SM, Woodruff TM. Generation of complement component C5a by ischemic neurons promotes neuronal apoptosis. FASEB J. 2012;26:3680–3690. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-202382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]