Abstract

Extracts from medicinal plants, many of which have been used for centuries, are increasingly tested in models of hepatotoxicity. One of the most popular models to evaluate the hepatoprotective potential of natural products is acetaminophen (APAP)-induced liver injury, although other hepatotoxicity models such as carbon tetrachloride, thioacetamide, ethanol and endotoxin are occasionally used. APAP overdose is a clinically relevant model of drug-induced liver injury. Critical mechanisms and signaling pathways, which trigger necrotic cell death and sterile inflammation, are discussed. Although there is increasing understanding of the pathophysiology of APAP-induced liver injury, the mechanism is complex and prone to misinterpretation, especially when unknown chemicals such as plant extracts are tested. This review discusses the fundamental aspects that need to be considered when using this model, such as selection of the animal species or in vitro system, timing and dose-responses of signaling events, metabolic activation and protein adduct formation, the role of lipid peroxidation and apoptotic versus necrotic cell death, and the impact of the ensuing sterile inflammatory response. The goal is to enable researchers to select the appropriate model and experimental conditions for testing of natural products that will yield clinically relevant results and allow valid interpretations of the pharmacological mechanisms.

Keywords: Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity, carbon tetrachloride, protein adducts, oxidant stress, lipid peroxidation, apoptosis and necrosis, innate immune response

1. Introduction

Acetaminophen (APAP) is a safe and effective analgesic and antipyretic drug. However, an overdose can cause hepatotoxicity in experimental animals and humans. In fact, APAP hepatotoxicity is the most frequent cause of acute liver failure of any etiology in the western world, not only drug-induced liver failure (Larson et al., 2005; Larson, 2007). In addition, APAP has been used extensively during the last 40 years as a model toxicant, which allows investigation of drug-induced cell death in vivo and in vitro. Many basic concepts of drug toxicity were developed using this model. As a consequence, APAP toxicity is one of the most popular models to test potentially hepatoprotective agents, especially natural products. In addition, the fact that APAP overdose causes not only direct cell death but also triggers an innate immune response has increased the popularity of this model among immunologists (Adams et al., 2010; Jaeschke et al., 2012). Unfortunately, too few researchers appreciate the complexity of the mechanisms of APAP-induced liver injury and misinterpretation of experimental results is common. As a result many highly conflicting data are being published. Although this may stimulate further research to refine the mechanism, when long-established fundamental principles of the model are ignored it not only wastes resources but prevents scientific progress. Therefore, the main objectives of this review are to summarize the current mechanistic understanding of APAP hepatotoxicity, and to discuss the different models being used and their relevance for the human pathophysiology. In addition, we point out pitfalls and common misconceptions of the mechanism and establish basic criteria that should be considered when using this or other models to test natural products.

2. Basic concepts in the mechanism of APAP toxicity

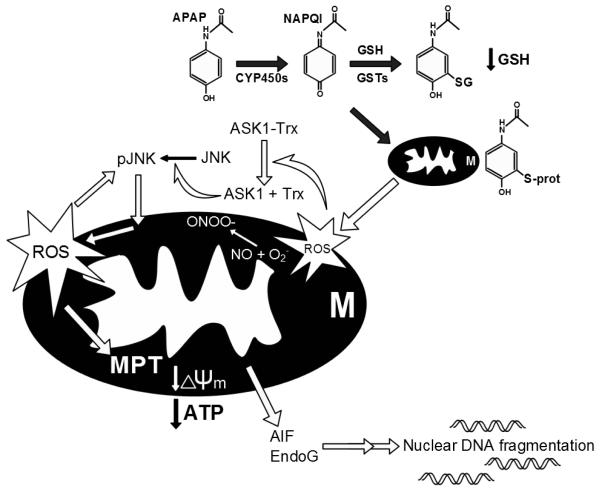

The intracellular signaling mechanisms of APAP-induced cell death were recently reviewed in great detail (Jaeschke et al., 2012a; Hinson et al., 2010; Jaeschke and Bajt, 2006). It is well established that the toxicity is initiated by the metabolism of a small fraction of the administered dose by P450 enzymes, mainly Cyp 2e1 and 1a2 (Zaher et al., 1998), to N-acetyl p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI). This reactive metabolite is detoxified by glutathione (GSH) resulting in extensive hepatic GSH depletion (Mitchell et al., 1973; Knight et al., 2001). Concurrently, an increasing amount of NAPQI reacts with protein sulfhydryl groups, causing the covalent adduction of cellular proteins (Jollow et al., 1973). Studies with the non-hepatotoxic regioisomer 3′-hydroxyacetanilide (AMAP) in mice indicated that the total protein binding in the cell is not as important as adducts in mitochondria (Tirmenstein and Nelson, 1989; Qiu et al., 2001). Mitochondrial protein binding triggers a mitochondrial oxidant stress (Jaeschke, 1990), which causes activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (Nakagawa et al., 2008) and c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (Hanawa et al., 2008) and the amplification of the mitochondrial oxidant stress and peroxynitrite formation by mitochondrial JNK translocation (Saito et al., 2010a) (Figure 1). The extensive oxidant stress finally triggers the opening of the membrane permeability transition (MPT) pore in the mitochondria with collapse of the membrane potential (Kon et al., 2004; Masubuchi et al., 2005; Ramachandran et al., 2011a; Loguidice and Boelsterli, 2011). The initial translocation of bax to the outer membrane and the later matrix swelling and rupture of the outer membrane after the MPT are responsible for the release of intermembrane proteins such as endonuclease G and apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) from mitochondria (Kon et al., 2004; Bajt et al., 2008). Both endonuclease G and AIF translocate to the nucleus and cause DNA fragmentation (Cover et al., 2005; Bajt et al., 2006, 2011). The collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential with ATP depletion and the nuclear degradation are key events leading to cellular necrosis. Thus, APAP-induced cell death is not caused by a single catastrophic event but by a series of events beginning with the reactive metabolite formation and initiation of mitochondrial dysfunction, which is amplified through the JNK pathway, ultimately leading to non-functional mitochondria and massive DNA degradation (Figure 1). The key point is that there are multiple intervention points where these mechanisms can be interrupted, which means that reduced cell death with a natural product intervention requires careful dissection of the protective mechanism, with recognition of potential pitfalls.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Acetaminophen (APAP) is converted to the electrophile NAPQI through phase I drug metabolism. NAPQI can be detoxified by glutathione (GSH) or bind to proteins. Binding to mitochondrial proteins causes mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, which activates apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). Translocation of JNK into mitochondria enhances the oxidative stress. The mitochondrial membrane permeability transition (MPT) occurs and the mitochondrial membrane potential is lost resulting in depletion of cellular ATP levels. The release of mitochondrial endonucleases (AIF and EndoG) leads to nuclear DNA fragmentation. The result of this sequence is cell necrosis.

3. Time and dose response of APAP hepatotoxicity

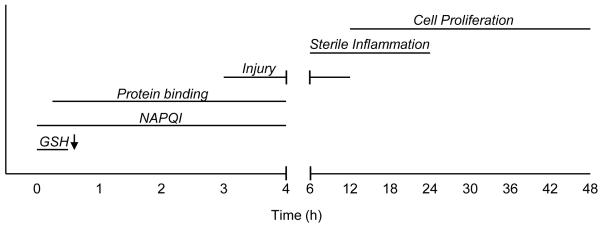

Dose- and time-dependence are fundamental to studying the adverse effects of any toxin. Although APAP is considered a dose-dependent hepatotoxicant, differences in toxicity can be difficult to document (Jaeschke, 1990). Instead of using multiple doses, it is sufficient to use a dose of ≥ 200 mg/kg for fasted mice or ≥ 400 mg/kg for fed mice to achieve significant liver toxicity (peak levels of >2000 U/L ALT) within 6 – 24 h. This approach is generally adequate for the study of beneficial effects of natural product interventions. In contrast, the sequential events in the pathophysiology make it necessary to investigate several time points after dosing. Metabolic activation must be verified between 0 and 2 h, times between 2 and 12 h are important for investigation of the intracellular mechanisms of cell death in hepatocytes, an inflammatory response develops in the time frame of 6 – 24 h, and regeneration occurs during the period of 24 – 72 h (Jaeschke et al., 2012a) (Figure 2). Most natural product studies rely on a single late time point. This is a problem, as any potential interference with metabolic activation would not allow conclusions about downstream effects, such as a compound’s antioxidant properties. Likewise, reduced inflammatory cell infiltration is dependent on the upstream injury and conclusions regarding a direct anti-inflammatory effect would only be justified if the natural product has no effect on metabolic activation and early injury, which needs to be experimentally verified. Thus, given the sequence of events in the mechanism of toxicity and their interdependency, it is absolutely critical to test the efficacy of natural products at different time points.

Figure 2.

Timeline of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. NAPQI formation begins immediately after acetaminophen (APAP) treatment. In mice, glutathione (GSH) levels drop precipitously in the first 0.5 h. Protein binding begins almost immediately after dosing and continues for 3-4 h (depending on the dose). Cell death begins during this time and continues until about 12 h post-treatment. A sterile inflammatory response occurs in the 6 – 24 h period. Finally, injury resolution, cell proliferation and liver regeneration begin at about 12 h and continue until about 72 h post-dosing.

4. Metabolic activation of APAP

4.1. GSH depletion and protein adducts

APAP hepatotoxicity is critically dependent on the formation of a reactive metabolite through the P450 system (Nelson, 1990). For most drug intervention studies, it is vital to assess a potential effect on the metabolic activation by evaluating the time course of hepatic GSH depletion during the first 30 min as a direct measure of NAPQI formation (Jaeschke, 1990; Bajt et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2012), and by measuring protein adducts in the total liver (Mitchell et al., 1973; Corcoran et al., 1985; Muldrew et al., 2002; McGill et al., 2011, 2012b; Xie et al., 2012) or, even better, in mitochondria (Tirmenstein and Nelson, 1989; McGill et al., 2012b; Xie et al., 2012) at 0.5 – 2 h after APAP. The plasma level of protein adducts can also be measured. This is particularly useful in humans because liver tissue is generally not available for overdose patients (Davern et al., 2006; James et al., 2009). In the past, protein adducts were mainly quantified by binding of radiolabeled APAP to the protein fraction of the liver (Mitchell et al., 1973; Corcoran et al., 1985). This approach is expensive and prone to error as the removal of >95% of the non-protein bound APAP or metabolites (radioactivity) is critical for the accuracy of the data. Later, antibodies were developed that allowed immunohistochemical detection of adducts in liver tissue (Roberts et al., 1991) and electrophoretic separation of individual proteins and detection by western blotting or mass spectrometry (Myers et al., 1995; Matthews et al., 1996; Qiu et al., 1998). Limitations of this approach include the sensitivity and difficulties in accurately quantifying these adducts. More recently, a method was developed involving separation of low molecular weight adducts (APAP-GSH conjugates) from APAP protein adducts, digestion of the proteins and then analysis of the cysteine adducts of APAP selectively derived from proteins by HPLC with electrochemical detection (Muldrew et al., 2002) or by mass spectrometry (McGill et al., 2011). This is based on the assumption that the vast majority of protein adducts are bound to cysteine residues on proteins (Hoffmann et al., 1985; Matthews et al., 1996; Nelson, 1990). This method allows for an accurate quantitation of the total adducts in the liver and in individual cell organelles such as mitochondria, but does not allow the identification of the adducted proteins.

In contrast to the measurement of the initial GSH depletion kinetics (≤ 30 min), evaluating hepatic GSH levels at later times (≥ 2 h) may not pick up subtle but important differences in NAPQI formation (Jaeschke et al., 2011a; Xie et al., 2012) and even later time points (≥ 6 h) will be more dependent on the re-synthesis rate, which can be affected by the degree of injury and, if food is available, by the feeding behavior. A case in point are the higher GSH levels observed 24 h after APAP in animals pretreated with a Moringa oleifera extract (Fakurazi et al., 2008). The authors concluded that the phytotherapeutic prevented liver injury by restoring the hepatic GSH content (Fakurazi et al., 2008). However, the higher GSH levels at this single, late time point could have been caused by inhibition of NAPQI formation or a faster recovery of hepatic GSH levels due to less injury.

4.2 P450 enzyme activities

Western blot analysis of Cyp2e1 can be useful to demonstrate the lack of a potential difference between experimental groups, however this reflects protein levels only, not enzyme activities. In addition, although Cyp2e1 is a major Cyp isoform that metabolizes APAP, it is not the only one (Zaher et al., 1998). To avoid some of these problems, use of a more general Cyp enzyme activity assay is preferable, such as the 7-ethoxy-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin (7EFC) deethylase assay which measures at least two P450 isoenzymes (cytochrome P450 1a2 and 2e1) (Buters et al., 1993), as described (Ramachandran et al., 2011b; Xie et al., 2012). This assay will give a more accurate picture of the metabolic capacity of the liver under the experimental conditions. This liver enzyme activity test will detect a potential P450-inducing effect of the natural product treatment in vivo but an inhibitory effect only if the compound is a suicide substrate, i.e., an irreversible inhibitor. A competitive inhibitor can only be identified in vitro by adding the test compound directly to the assay (Xie et al., 2012). In addition to the conventional enzyme assays, the induction/inhibition of multiple P450 isoenzymes by drugs and chemicals can be assessed using a cocktail of specific substrates in vivo and in vitro (Dierks et al., 2001; Fuhr et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2012). Although this allows the evaluation of a number of isoenzymes at the same time, which is an advantage especially in humans, the assays generally require analyses of substrates and products by liquid chromatography – tandem mass spectrometry. Therefore, these types of approaches are rarely used in studies where herbal products are evaluated in hepatotoxicity models (Yamaura et al., 2011). In contrast, these assays are mainly being used to screen chemicals for drug-drug interactions including the effects of phytopharmaceuticals on P450 enzyme induction or inhibition (Sevior et al., 2010; Cordier and Steenkamp, 2011; Zadoyan and Fuhr, 2012).

Because virtually all experiments designed to test whole plant extracts or individual components use a pretreatment regimen, it is absolutely imperative to carefully evaluate their potential effect on the metabolic activation of APAP. Given that NAPQI formation and protein binding are the most upstream and critical events for the initiation of the toxicity, any interference with this process, even if it is subtle, can have a profound effect on APAP-induced liver injury. Unfortunately, this is the most glaring omission of most natural product testing experiments in the literature. A case in point is the protective effect of green tea extract against APAP toxicity when used as pretreatment (Oz et al., 2004; Salminen et al., 2012). This protection is not due to its antioxidant effect (Oz et al., 2004) but is caused by inhibition of drug-metabolizing enzymes (Chen et al., 2009; Weng et al., 2012) resulting in reduced protein adduct formation (Salminen et al., 2012).

5. Model considerations in vivo and in vitro

5.1. In vivo models of APAP toxicity

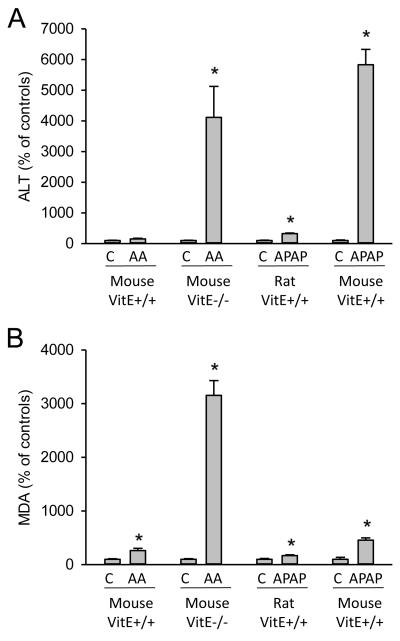

APAP overdose can cause severe liver injury in humans involving protein adduct formation (Davern et al., 2006; James et al., 2009), mitochondrial damage and nuclear DNA fragmentation (McGill et al., 2012a), release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as high mobility group box 1 proteins (Antoine et al., 2009, 2012) and mitochondrial DNA (McGill et al., 2012a). Any experimental model designed to test the hepatoprotective effect of natural products should have these features. Thus, for in vivo experiments, the mouse is the preferred model as the injury most closely resembles the human pathophysiology in both mechanism and dose-dependency. The only significant difference in APAP hepatotoxicity between mice and humans is the more delayed toxicity in humans (peak ALT activities: 24-48 h after exposure) compared to mice (peak ALT: 6-12 h) (Larson, 2007). This may in part be explained by the more delayed absorption from digested tablets in patients compared to the dissolved APAP generally administered to mice. There are also strain differences in the susceptibility of mice that need to be considered (Harrill et al., 2009) and the fact that female mice are in most cases less sensitive (Dai et al., 2006; Masubuchi et al., 2011), which has been attributed to higher GSH synthesis rate in these animals (Masubuchi et al., 2011). In contrast, the rat, although popular for natural product testing, is a poor model as most rat strains are largely insensitive to APAP toxicity (Mitchell et al., 1973; McGill et al., 2012b). Even a high dose of ≥1 g/kg generally does not cause relevant liver injury (Figure 3). Although GSH depletion and protein adducts can be measured, the lower adducts in rat liver mitochondria compared to mice appear to be insufficient to initiate enough mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent amplification events to lead to necrotic cell death (McGill et al., 2012b). Thus, sensitive mouse strains are the most clinically relevant models of APAP hepatotoxicity for natural product testing in vivo. An example of the fundamental differences between assessing protective effects of phytotherapeutics in rats and mice are the following studies: In a rat study, a dose of 3 g/kg resulted in an increase of plasmas ALT levels of about 3-fold compared to baseline and the phytotherapeutic attenuated this modest liver injury by 33% (Ajith et al., 2007). Any histological changes in this rat model were minimal and difficult to detect. On the other hand, in a mouse study, ALT increases were >60-fold of baseline after 300 mg/kg APAP and the reduction by the phytotherapeutic was 75% (Wan et al., 2012). Histological changes caused by APAP toxicity and the protective effect of the drug were readily observed.

Figure 3.

A) Liver injury (plasma alanine aminotransferase activity) and B) malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were assessed in untreated controls and in different models of drug-induced liver injury. Data are shown for a model of allyl alcohol-induced liver injury (0.1 mmol/kg AA) in mice fed a regular diet (Vit E+/+) or a vitamin E–deficient diet for 4 weeks (data adapted from Knight et al., 2003 and Jaeschke et al., 1987). Other data are from models of acetaminophen (APAP)-induced liver injury in rats (adapted from Ajit et al., 2007) and mice (adapted from Wu et al., 2010) fed a regular diet. The comparison clearly indicates the high susceptibility to lipid peroxidation (LPO) of animals on a vitamin E-deficient diet. In contrast, APAP causes similar injury in mice on a regular diet but very little LPO indicating that LPO is not the mechanism of cell death. The comparison between rats and mice documents the low susceptibility of rats to APAP-induced LPO or liver injury.

5.2 In vitro models of APAP toxicity

The best and most successfully applied in vitro models are primary cultured mouse hepatocytes, which generally reproduce the in vivo pathophysiology (Shen et al., 1992; Nagai et al., 2002; Bajt et al., 2004; Kon et al., 2004, 2010; Ni et al., 2012; Burke et al., 2010). In contrast to intact rats, dose-dependent glutathione depletion, oxidant stress and cytotoxicity (necrosis) have also been shown in cultured rat hepatocytes (Ellouk-Achard et al., 1995; Rousar et al., 2009; Yang and Salminen, 2011). Because freshly isolated hepatocytes rapidly lose their P450 enzyme activity, it is necessary to start the experiment (APAP treatment) shortly after isolation and adherence of the cells. Any significant delay, i.e. culture overnight, reduces the sensitivity and increases the risk that unrelated mechanisms of toxicity are introduced. A caveat of primary rodent hepatocyte experiments is the use of room air (21% oxygen) in standard tissue culture incubators. Physiological oxygen concentrations in liver sinusoids are between 4-10% (Kietzmann and Jungermann, 1997). As a consequence of hyperoxic conditions in these in vitro experiments, higher reactive oxygen formation causes accelerated cell death (Yan et al., 2010). This may be the reason for more lipid peroxidation and protection by vitamin E in vitro (Nagai et al., 2002) compared to in vivo (Knight et al., 2003). Because of the low levels of P450 enzymes compared to primary hepatocytes (Lin et al., 2012), immortalized cell lines such a human hepatoma cells HepG2, Hep3B, Huh7, etc, are not appropriate models for APAP toxicity. This does not mean that there is no toxicity in these cell lines. In fact, high levels of APAP do cause injury (Lin et al., 2012), but the mode of cell death is apoptosis (Boulares et al., 2002; Manov et al., 2004; Kass et al., 2003). In contrast to primary hepatocytes, there is little GSH depletion, protein binding or mitochondrial dysfunction suggesting toxicity independent of reactive metabolite formation (Dai and Cederbaum, 1995; McGill et al., 2011). In addition, N-acetyl cysteine, the clinical antidote for APAP overdose, which also effectively inhibits APAP toxicity in mice in vivo (James et al., 2003; Saito et al., 2010b) and in vitro (Bajt et al., 2004), does not protect HepG2 cells (Manov et al., 2004). Thus, the mechanism of toxicity in hepatoma cell lines is not relevant for the human disease process and natural product intervention studies that are effective in these cell lines may not be therapeutically relevant. An exception to this rule is the metabolically competent cell line HepaRG (Guillouzo et al., 2007), which reproduces key mechanisms of toxicity such as protein adducts, GSH depletion, mitochondrial dysfunction and necrotic cell death after APAP (McGill et al., 2011). In addition, HepG2 cells transfected with Cyp2e1 enzyme activities can also be a useful model to study APAP toxicity in cell lines (Dai and Cederbaum, 1995). The caveat of metabolically competent cell lines is that they are still hepatoma cells, which may have altered signaling pathways compared to primary hepatocytes. Since it is possible to transfect and stably express individual drug metabolizing enzymes in hepatoma cell lines, these cells can be a valuable tool to study drug metabolism (Donato et al., 2008). However, the main application of hepatoma cells overexpressing individual P450 enzymes is not to study drug toxicity but to screen for potential enzyme inhibitors (Donato et al., 2008).

6. Oxidant stress and lipid peroxidation

One of the most invoked mechanisms of cell death by APAP aside from protein adduct formation is oxidant stress with lipid peroxidation (LPO). Initially it was hypothesized that reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated by P450 enzymes during the metabolism of APAP (Wendel and Feuerstein, 1981). However, this conclusion has been disputed because no direct evidence for ROS formation was observed during the metabolism phase (Smith and Jaeschke, 1989; Bajt et al., 2004). In contrast, mitochondria were identified as the main source of ROS and peroxynitrite formation (Jaeschke, 1990; Cover et al., 2005). As most protective natural product interventions reduce LPO, the conclusion is always that the compounds act as antioxidants (e.g. Küpeli et al., 2006; Hsu et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2008; Yuan et al., 2010). However, in most of these studies there is no direct evidence for an oxidant stress; the conclusions are mainly based on minor changes of “malondialdehyde (MDA)” levels, which should be more correctly termed thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS). Although it is now well established that APAP causes formation of ROS and peroxynitrite in mice in vivo (Jaeschke, 1990; Hinson et al., 1998; Knight et al., 2001; Cover et al., 2005) and in vitro (Bajt et al., 2004, Burke et al., 2010; McGill et al., 2011), there appears to be much less oxidant stress in rats after APAP overdose (McGill et al., 2012b). In addition, scavenging of ROS and RNS with GSH or NAC treatment is highly effective in protecting against APAP toxicity in mice (Knight et al., 2002; James et al., 2003), which is mainly caused by the accelerated recovery of the mitochondrial GSH content (Saito et al., 2010b). However, despite the oxidant stress, the role of LPO in the pathophysiology is questionable. Early data on the dramatic increase in LPO during APAP hepatotoxicity were recorded using mice on a diet deficient in vitamin E and high in polyunsaturated fatty acids (Wendel et al., 1979, 1982; Wendel and Feuerstein, 1981), which made the animals highly susceptible to LPO and actually shifted the entire mechanism of toxicity (Jaeschke et al., 2003). However, animals on a normal diet, i.e. with adequate vitamin E levels, showed very little if any LPO and treatment with α- or γ-tocopherol did not protect (Knight et al., 2003). Thus, LPO can be considered a marker for oxidant stress in the tissue but it is unlikely the mechanism of cell death (Jaeschke et al., 2003). In support of this conclusion, LPO parameters such as ethane exhalation, hydroxy fatty acid formation, isoprostanes and TBARS levels increase by 30- to 50-fold above baseline under conditions of drug toxicity (APAP and allyl alcohol in vitamin E-deficient animals, tert-butyl hdroperoxide) where LPO is the cause of cell death (Wendel et al., 1979; Jaeschke et al., 1987; Mathews et al., 1994) (Figure 3). For most APAP data, LPO parameters such as TBARS levels are increased by less than 2-to 4-fold above baseline (e.g., Ajith et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2008; Kumari and Kakkar, 2012) suggesting that LPO during APAP toxicity is an order of magnitude below the level needed to cause cell injury (Figure 3). Consistent with the lower oxidant stress in rats, TBARS levels generally increase <2-fold (Figure 3).

7. Mode of cell death – apoptosis or necrosis

7.1 Apoptotic morphology and caspase activation

Apoptotic and necrotic cell death can be readily distinguished based on morphological features. The main characteristics of apoptosis, as seen in Fas and TNF receptor-induced apoptosis, are cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation and margination, formation of apoptotic bodies and, generally, lack of inflammation (Gujral et al., 2002; Jaeschke and Lemasters, 2003). Apoptosis is a single cell event. In contrast, necrosis is characterized by vacuolation, cell swelling, nuclear degradation and massive release of cell contents from a large continuous area of cells as shown in APAP hepatotoxicity (Gujral et al., 2002; Jaeschke et al., 2011b). Thus, based on morphological features, APAP-induced cell death can be clearly defined as necrosis (Gujral et al., 2002; Jaeschke et al., 2011b). In support of this conclusion, there is never any relevant caspase activation during APAP toxicity in mice (Lawson et al., 1999; Adams et al., 2001; El-Hassan et al., 2003; Jaeschke et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2010b) or humans (McGill et al, 2012a; Antoine et al., 2012). In addition, various pancaspase inhibitors do not protect against APAP-induced liver injury (Lawson et al., 1999; Gujral et al., 2002; Jaeschke et al., 2006; Antoine et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2010b) despite the fact that these inhibitors are close to 100% effective in models of apoptosis (Jaeschke et al., 1998; Bajt et al., 2000). In some cases, the alleged protection by a caspase inhibitor (e.g. El-Hassan et al., 2003; Hu and Colletti, 2010) is actually caused by the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Jaeschke et al., 2006, 2011b), which is an effective P450 inhibitor (Yoon et al., 2006). Further confusion comes from occasional reports showing that there is a minor, transient activation of caspases after APAP overdose in fed mice (Antoine et al., 2010), however this does not lead to apoptotic cell death (Williams et al., 2011b).

Also, the fact that features originally considered specific to apoptosis such as mitochondrial bax translocation (Adams et al., 2001; El-Hassan et al., 2003; Jaeschke and Bajt, 2006; Bajt et al., 2008) and release of cytochrome c and smac/DIABLO from mitochondria through bax pores (Bajt et al., 2008) have been observed during APAP toxicity leads some to incorrectly conclude that apoptosis might be involved. Induction of bax and procaspase-3 expression has also been reported during APAP hepatotoxicity (Yuan et al., 2010; Kumari and Kakkar, 2012). However, apoptosis is generally not a transcriptionally regulated process: every cell has sufficient baseline levels of these proteins to undergo apoptosis upon stimulation. Thus, induction of bax or procaspase 3 is not evidence for apoptosis. Even a minor indication of caspase-3 processing on a western blot (Yuan et al., 2010) does not support the conclusion that there is relevant apoptotic cell death (Williams et al., 2011b) (Figure 4). Only a proportional increase in caspase activity and caspase processing with morphological evidence of apoptosis in the tissue and the elimination of these changes with a pancaspase inhibitor, as demonstrated in models of Fas and TNF receptor-mediated apoptosis (Jaeschke et al., 1998; Bajt et al, 2000), is convincing evidence for involvement of apoptosis as a pathophysiologically relevant cell death process.

Figure 4.

Caspase-3 fluorescent activity assay and western blotting. C57BL/6 mice were treated intraperitoneally with saline vehicle (6 h), 300 mg/kg APAP (0.5, 6 or 24 h), or 700 mg/kg galactosamine (GalN)-100 μg/kg endotoxin (ET) (6 h). (A) Caspase-3 activity was determined by the Ac-DEVD-AFC fluorometric assay (Enzo Life Sciences, Plymouth Meeting, PA) using total liver homogenate and expressed as the change in relative fluorescence units (RFU) per minute per mg protein as previously described (Bajt et al., 2000). (B) Western blotting was also performed using total liver homogenate with an antibody which recognizes full length (pro-form) and cleaved (active) caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) as previously described (Bajt et al., 2000).

7.2 DNA fragmentation

Another controversial feature of apoptosis is nuclear DNA fragmentation. Internucleosomal DNA fragmentation, detectable as a DNA ladder on agarose gels (Ray et al., 1990) and DNA strand breaks detectable by the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (Lawson et al., 1999), is often mistaken as evidence for apoptosis during APAP hepatotoxicity. However, the fundamental difference between DNA fragmentation during apoptosis, where it is mediated by caspase-activated DNase, and APAP-induced necrosis is that the DNA damage is caused by mitochondria-derived endonuclease G and apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) (Bajt et al., 2006; 2011). As a consequence, APAP-induced DNA fragmentation is not affected by a caspase inhibitor but is eliminated by preventing mitochondrial dysfunction (Cover et al., 2005; Bajt et al., 2008). In contrast to apoptosis, DNA fragmentation during APAP-induced necrosis produces both internucleosomal DNA fragments and larger DNA pieces (Jahr et al., 2001).

Taken together, there is no evidence of relevant apoptotic cell death during APAP-induced liver injury in humans, in mice or rats in vivo, or in cultured rodent or human hepatocytes. Caution should be exercised when interpreting data based on a single parameter that appears to contradict a large body of literature on the mechanism of APAP toxicity. The best strategy to avoid misinterpretations is to use positive controls for apoptosis and compare quantitative changes of these parameters in apoptosis models and in the APAP model.

8. Sterile inflammation

The extensive APAP-induced necrosis causes the release of intracellular contents of hepatocytes, including HMGB1, mtDNA, nuclear DNA, and others. These compounds are collectively referred to as damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) (Antoine et al., 2009, 2012; Martin-Murphy et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2011a; McGill et al., 2012a). This occurs in mice and in humans after APAP overdose. DAMPs are ligands for various pattern recognition receptors (Jeannin et al., 2008), which can trigger the transcriptional activation of proinflammatory genes such as TNF-α, IL-1β, CXC chemokines, and others, mainly in macrophages. The inflammatory mediators recruit leukocytes, especially neutrophils, during the early injury phase (Lawson et al., 2000; Cover et al., 2006), however their activation is limited (Williams et al., 2010a). In addition, monocytes are recruited during the late injury phase (Dambach et al., 2002; Holt et al., 2008). Based on the many conflicting results published about inflammatory cells in APAP hepatotoxicity, it seems controversial whether or not these leukocytes actually directly contribute to the injury. However, the preponderance of the experimental evidence supports the hypothesis that the recruited leukocytes do not contribute to liver injury, but rather are needed for removal of necrotic cell debris in preparation for liver regeneration (reviewed by Jaeschke et al., 2012b). Interestingly, cytokines produced during the sterile inflammation may directly affect intracellular signaling events. For example, IL-4 can promote GSH synthesis and recovery (Ryan et al., 2012), which could protect by attenuating the mitochondrial oxidant stress. IL-10 and IL-15 are other examples. These cytokines protect by limiting induction of iNOS and thus peroxynitrite formation (Bourdi et al., 2002; Hou et al., 2012). These effects may explain the protective effect of Kupffer cell activation during APAP hepatotoxicity (Ju et al., 2002). The important point is that the sterile inflammatory response is clearly dependent on the injury. Thus, any natural product intervention that reduces cell death will reduce inflammatory mediator formation and leukocyte recruitment (Sener et al., 2006; Toklu et al., 2006). Therefore, conclusions regarding potential anti-inflammatory properties of a natural product are only justified when experiments have ruled out that the compound interferes with drug metabolism and/or cell death pathways.

9. Non-acetaminophen models of hepatotoxicity

Several other models of liver injury have been used to test the hepatoprotective potential of natural products. Among the most popular are carbon tetrachloride and thioacetamide. Unfortunately, these models are subject to some of the same concerns as APAP. The frequent use of pretreatment and cotreatment regimens and reliance on a single time point are especially common problems.

9.1 Carbon tetrachloride

Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) is a once-popular industrial chemical that is now strictly regulated in many countries. Metabolism produces trichloromethyl radicals that can bind to proteins and DNA and cause direct damage to these macromolecules (Weber et al., 2003). They can also abstract hydrogen from polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), forming lipid radicals. The addition of O2 yields lipid peroxyl radicals which can react with other PUFAs to form new lipid radicals in a propagation cycle. The result is lipid peroxidation and liver injury (Weber et al., 2003). Acute administration of a large dose of CCl4 causes severe necrosis, while chronic administration of lower doses is frequently used to induce hepatic fibrosis. Like APAP, CCl4 is metabolized by P450s (McLean and McLean, 1966; Weddle et al., 1976; Weber et al., 2003). Importantly, Cyp2e1 knockout mice have been shown to be resistant to CCl4-induced liver injury (Wong et al., 1998). The dependence of CCl4 toxicity on P450-mediated metabolism means that, similar to APAP, interventions which inhibit metabolism will likely protect against injury. Unfortunately, many studies showing protection against CCl4 hepatotoxicity by herbal therapeutics have relied on either pretreatment or cotreatment (Kang et al., 2008; Dhanasekaran et al., 2009; Risal et al., 2012; Tzeng et al., 2012). Thus, any conclusions regarding an anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, or anti-fibrotic effect in these and similar studies are questionable at best. In fact, Risal et al. (2012) reported that their intervention restored P450 activity compared with CCl4 alone. Though the authors concluded that the protection resulted from antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, the lack of P450 inhibition suggests that the test compound prevented CCl4 metabolism, as CCl4 is known to be a suicide substrate of P450s via the trichloromethyl radical metabolite (Weber et al., 2003). Covalent binding to proteins and irreversible P450 inhibition may be useful indicators of CCl4 metabolism in natural product testing.

9.2 Thioacetamide

The hepatotoxic effects of thioacetamide (TAA), another industrial chemical, are also eliminated in Cyp2e1-null mice (Kang et al., 2008). This study provided an important proof-of-principal: the authors directly demonstrated that inhibition of thioacetamide metabolism prevented downstream increases in oxidative stress and cytokine production (Kang et al., 2008). Chronic administration of TAA is commonly used as a model of fibrosis, but the compound can also cause acute liver injury. Unfortunately, as with APAP and carbon tetrachloride, animals are often pretreated or cotreated with the natural product being tested (Galisteo et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2011; Jain and Singhai, 2011), making it difficult to determine whether protection results from clinically useful therapeutic effects or merely from inhibition of metabolism.

9.3 Additional Hepatotoxicity Models

Ethanol, endotoxin and allyl alcohol are additional hepatotoxic agents available to evaluate phytopharmaceuticals. High doses of ethanol (binge treatments) have been used to test the hepatoprotective effects of phytotherapeutics (Chotimarkorn and Ushio, 2008; Hu et al., 2010; Nwozo and Oyinloye, 2011; Wang et al., 2012). In addition, allyl alcohol is a liver toxicant that has occasionally been used in mice to study the effect of plant extracts (Remirez et al., 1997). The adverse effects of both ethanol and allyl alcohol are dependent on the metabolism by alcohol dehydrogenase (to form a reactive aldehyde) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (to detoxify this aldehyde) (Jaeschke et al., 1987). Thus, assessment of the potential effect of the natural products on alcohol metabolism is critical for the mechanistic interpretation of the data. In addition, the concerns discussed for APAP also apply to alcohols regarding qualitative and quantitative aspects of lipid peroxidation as mechanism of injury. Furthermore, unless susceptible animals (Jaeschke et al., 1987, 1992) are used, the degree of injury is minimal, which makes interpretation of protective effects difficult.

Endotoxin is another model compound that is available to study the effect of natural products. Although endotoxin alone does not cause relevant liver injury, it can be used to evaluate the effect of natural products on inflammatory cytokine formation (Kang et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2012). In order to trigger liver injury, the combination of galactosamine/endotoxin (Gal/ET) is generally used in mice (Galanos et al., 1979) or rats (Hong et al., 2009). A number of phytotherapeutics have been tested in the Gal/ET model (Zhang et al., 2010; Cerny et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2012). However, the problem is the sequential events that take place in this model. ET activates Kupffer cells to generate TNF-α, which then activates and recruits neutrophils into the liver (Schlayer et al., 1988). TNF-α signaling in combination with blocking transcription with Gal leads to parenchymal cell apoptosis, which triggers neutrophil extravasation and amplification of the injury (Jaeschke et al., 1998). Thus, if a phytotherapeutic affects TNF-α formation in Kupffer cells, all other subsequent effects are inhibited. Similar to APAP hepatotoxicity, the intervention points have to be carefully investigated; a single time point is generally insufficient to assess the mechanism of protection.

10. Summary and future perspectives

As outlined in this review, the mechanism of APAP hepatotoxicity is highly complex. When this or other models are used to test the hepatoprotective potential of natural products, it is vital to consider the critical importance of metabolic activation and protein adduct formation and other mechanisms in the sequence of events leading to cell death. Unfortunately, the current literature indicates that most natural product studies using APAP overdose suffer from poor choice of models, lack specific assessment of drug metabolism, rely on a single time point, etc. These severe shortcomings not only call into question any mechanistic conclusions (anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, etc) but also challenge the relevance of these compounds as hepatoprotective agents. Progress in the area of phytotherapeutics and other natural product testing with more in-depth mechanistic understanding and more clinically relevant findings will only be possible when investigators consider the growing mechanistic understanding of the hepatotoxicity model and avoid the many pitfalls outlined in this review.

Acknowledgements

Work in the authors’ laboratory was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants AA12916 and DK070195 and by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (5P20RR021940-07) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8 P20 GM103549-07) from the National Institutes of Health. M.R. McGill and C.D. Williams were supported by the “Training Program in Environmental Toxicology” (T32 ES007079-26A2) from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams DH, Ju C, Ramaiah SK, Uetrecht J, Jaeschke H. Mechanisms of immune-mediated liver injury. Toxicol. Sci. 2010;115:307–321. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams ML, Pierce RH, Vail ME, White CC, Tonge RP, Kavanagh TJ, Fausto N, Nelson SD, Bruschi SA. Enhanced acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in transgenic mice overexpressing BCL-2. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;60:907–915. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.5.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajith TA, Hema U, Aswathy MS. Zingiber officinale Roscoe prevents acetaminophen-induced acute hepatotoxicity by enhancing hepatic antioxidant status. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007;45:2267–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine DJ, Jenkins RE, Dear JW, Williams DP, McGill MR, Sharpe MR, Craig DG, Simpson KJ, Jaeschke H, Park BK. Molecular forms of HMGB1 and keratin-18 as mechanistic biomarkers for mode of cell death and prognosis during clinical acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J. Hepatol. 2012;56:1070–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Antoine DJ, Williams DP, Kipar A, Jenkins RE, Regan SL, Sathish JG, Kitteringham NR, Park BK. High-mobility group box-1 protein and keratin-18, circulating serum proteins informative of acetaminophen-induced necrosis and apoptosis in vivo. Toxicol. Sci. 2009;112:521–531. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine DJ, Williams DP, Kipar A, Laverty H, Park BK. Diet restriction inhibits apoptosis and HMGB1 oxidation and promotes inflammatory cell recruitment during acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Mol. Med. 2010;16:479–490. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Bajt ML, Cover C, Lemasters JJ, Jaeschke H. Nuclear translocation of endonuclease G and apoptosis-inducing factor during acetaminophen-induced liver cell injury. Toxicol. Sci. 2006;94:217–225. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Farhood A, Lemasters JJ, Jaeschke H. Mitochondrial bax translocation accelerates DNA fragmentation and cell necrosis in a murine model of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;324:8–14. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.129445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Knight TR, Lemasters JJ, Jaeschke H. Acetaminophen-induced oxidant stress and cell injury in cultured mouse hepatocytes: protection by N-acetyl cysteine. Toxicol. Sci. 2004;80:343–349. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Lawson JA, Vonderfecht SL, Gujral JS, Jaeschke H. Protection against Fas receptor-mediated apoptosis in hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells by a caspase-8 inhibitor in vivo: evidence for a postmitochondrial processing of caspase-8. Toxicol. Sci. 2000;58:109–117. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/58.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Ramachandran A, Yan HM, Lebofsky M, Farhood A, Lemasters JJ, Jaeschke H. Apoptosis-inducing factor modulates mitochondrial oxidant stress in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 2011;122:598–605. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulares AH, Zoltoski AJ, Stoica BA, Cuvillier O, Smulson ME. Acetaminophen induces a caspase-dependent and Bcl-XL sensitive apoptosis in human hepatoma cells and lymphocytes. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;90:38–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.900108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdi M, Masubuchi Y, Reilly T, Amouzadeh H, Martin J, George JW, Shah AG, Pohl LR. Protection against acetaminophen-induced liver injury and lethality by interleukin 10: role of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Hepatology. 2002;35:289–298. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke AS, MacMillan-Crow LA, Hinson JA. Reactive nitrogen species in acetaminophen-induced mitochondrial damage and toxicity in mouse hepatocytes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2010;23:1286–1292. doi: 10.1021/tx1001755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buters JT, Schiller CD, Chou RC. A highly sensitive tool for the assay of cytochrome P450 enzyme activity in rat, dog and man. Direct fluorescence monitoring of the deethylation of 7-ethoxy-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1993;46:1577–1584. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90326-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerný D, Lekić N, Váňová K, Muchová L, Hořínek A, Kmoníčková E, Zídek Z, Kameníková L, Farghali H. Hepatoprotective effect of curcumin in lipopolysaccharide/-galactosamine model of liver injury in rats: relationship to HO-1/CO antioxidant system. Fitoterapia. 2011;82:786–791. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Sun CK, Han GZ, Peng JY, Li Y, Liu YX, Lv YY, Liu KX, Zhou Q, Sun HJ. Protective effect of tea polyphenols against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in mice is significantly correlated with cytochrome P450 suppression. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1829–1835. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chotimarkorn C, Ushio H. The effect of trans-ferulic acid and gamma-oryzanol on ethanol-induced liver injury in C57BL mouse. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:951–958. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SD, Pumford NR, Khairallah EA, Boekelheide K, Pohl LR, Amouzadeh HR, Hinson JA. Selective protein covalent binding and target organ toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1997;143:1–12. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.8074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran GB, Racz WJ, Smith CV, Mitchell JR. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on acetaminophen covalent binding and hepatic necrosis in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1985;232:864–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordier W, Steenkamp V. Drug interactions in African herbal remedies. Drug Metabol. Drug Interact. 2011;26:53–63. doi: 10.1515/DMDI.2011.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover C, Liu J, Farhood A, Malle E, Waalkes MP, Bajt ML, Jaeschke H. Pathophysiological role of the acute inflammatory response during acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006;216:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover C, Mansouri A, Knight TR, Bajt ML, Lemasters JJ, Pessayre D, Jaeschke H. Peroxynitrite-induced mitochondrial and endonuclease-mediated nuclear DNA damage in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;315:879–887. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.088898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Cederbaum AI. Cytotoxicity of acetaminophen in human cytochrome P4502E1-transfected HepG2 cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;273:1497–1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai G, He L, Chou N, Wan YJ. Acetaminophen metabolism does not contribute to gender difference in its hepatotoxicity in mouse. Toxicol. Sci. 2006;92:33–41. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambach DM, Watson LM, Gray KR, Durham SK, Laskin DL. Role of CCR2 in macrophage migration into the liver during acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in the mouse. Hepatology. 2002;35:1093–1103. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davern TJ, 2nd, James LP, Hinson JA, Polson J, Larson AM, Fontana RJ, Lalani E, Munoz S, Shakil AO, Lee WM, Acute Liver Failure Study Group Measurement of serum acetaminophen-protein adducts in patients with acute liver failure. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:687–694. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanasekaran M, Ignacimuthy S, Agastian P. Potential hepatoprotective activity of ononitol monohydrate isolated from Cassia tora L. on carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity in wistar rats. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:891–895. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierks EA, Stams KR, Lim HK, Cornelius G, Zhang H, Ball SE. A method for the simultaneous evaluation of the activities of seven major human drug-metabolizing cytochrome P450s using an in vitro cocktail of probe substrates and fast gradient liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2001;29:23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato MT, Lahoz A, Castell JV, Gómez-Lechón MJ. Cell lines: a tool for in vitro drug metabolism studies. Curr. Drug Metab. 2008;9:1–11. doi: 10.2174/138920008783331086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hassan H, Anwar K, Macanas-Pirard P, Crabtree M, Chow SC, Johnson VL, Lee PC, Hinton RH, Price SC, Kass GE. Involvement of mitochondria in acetaminophen-induced apoptosis and hepatic injury: roles of cytochrome c, Bax, Bid, and caspases. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2003;191:118–129. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellouk-Achard S, Mawet E, Thibault N, Dutertre-Catella H, Thevenin M, Claude JR. Protective effect of nifedipine against cytotoxicity and intracellular calcium alterations induced by acetaminophen in rat hepatocyte cultures. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 1995;18:105–117. doi: 10.3109/01480549509014315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakurazi S, Hairuszah I, Nanthini U. Moringa oleifera Lam prevents acetaminophen induced liver injury through restoration of glutathione level. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008;46:2611–2615. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhr U, Jetter A, Kirchheiner J. Appropriate phenotyping procedures for drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters in humans and their simultaneous use in the “cocktail” approach. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;81:270–283. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanos C, Freudenberg MA, Reutter W. Galactosamine-induced sensitization to the lethal effects of endotoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:5939–5943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galisteo M, Suarez A, del Pilar Montilla M, del Pilar Utrilla M, Jimenez J, Gil A, Faus MJ, Navarro M. Antihepatotoxic activity of Rosmarinus tomentosus in a model of acute hepatic damage induced by thioacetamide. Phytother. Res. 2000;14:522–526. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200011)14:7<522::aid-ptr660>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillouzo A, Corlu A, Aninat C, Glaise D, Morel F, Guguen-Guillouzo C. The human hepatoma HepaRG cells: A highly differentiated model for studies of liver metabolism and toxicity of xenobiotics. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2007;168:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujral JS, Knight TR, Farhood A, Bajt ML, Jaeschke H. Mode of cell death after acetaminophen overdose in mice: apoptosis or oncotic necrosis? Toxicol. Sci. 2002;67:322–328. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/67.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanawa N, Shinohara M, Saberi B, Gaarde WA, Han D, Kaplowitz N. Role of JNK translocation to mitochondria leading to inhibition of mitochondria bioenergetics in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:13565–13577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708916200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrill AH, Ross PK, Gatti DM, Threadgill DW, Rusyn I. Population-based discovery of toxicogenomics biomarkers for hepatotoxicity using a laboratory strain diversity panel. Toxicol. Sci. 2009;110:235–243. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson JA, Pike SL, Pumford NR, Mayeux PR. Nitrotyrosine-protein adducts in hepatic centrilobular areas following toxic doses of acetaminophen in mice. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1998;11:604–607. doi: 10.1021/tx9800349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson JA, Roberts DW, James LP. Mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced liver necrosis. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2010;196:369–405. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00663-0_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann KJ, Streeter AJ, Axworthy DB, Baillie TA. Identification of the major covalent adduct formed in vitro and in vivo between acetaminophen and mouse liver proteins. Mol. Pharmacol. 1985;27:566–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt MP, Cheng L, Ju C. Identification and characterization of infiltrating macrophages in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008;84:1410–1421. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0308173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JY, Lebofsky M, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Oxidant stress-induced liver injury in vivo: role of apoptosis, oncotic necrosis, and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G572–G581. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90435.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou HS, Liao CL, Sytwu HK, Liao NS, Huang TY, Hsieh TY, Chu HC. Deficiency of interleukin-15 enhances susceptibility to acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CC, Lin KY, Wang ZH, Lin WL, Yin MC. Preventive effect of Ganoderma amboinense on acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:946–950. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Shen G, Zhao W, Wang F, Jiang X, Huang D. Paeonol, the main active principles of Paeonia moutan, ameliorates alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Lin KJ, Cheng YW, Hsu CA, Yang SS, Shyur LF. Hepatoprotective effect and mechanistic insights of deoxyelephantopin, a phyto-sesquiterpene lactone, against fulminant hepatitis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012 Jun 28; doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.01.013. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H. Glutathione disulfide formation and oxidant stress during acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice in vivo: the protective effect of allopurinol. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;255:935–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Bajt ML. Intracellular signaling mechanisms of acetaminophen-induced liver cell death. Toxicol. Sci. 2006;89:31–41. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Cover C, Bajt ML. Role of caspases in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Life Sci. 2006;78:1670–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Fisher MA, Lawson JA, Simmons CA, Farhood A, Jones DA. Activation of caspase 3 (CPP32)-like proteases is essential for TNF-alpha-induced hepatic parenchymal cell apoptosis and neutrophil-mediated necrosis in a murine endotoxin shock model. J. Immunol. 1998;160:3480–3486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Kleinwaechter C, Wendel A. The role of acrolein in allyl alcohol-induced lipid peroxidation and liver cell damage in mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1987;36:51–57. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Kleinwaechter C, Wendel A. NADH-dependent reductive stress and ferritin-bound iron in allyl alcohol-induced lipid peroxidation in vivo: the protective effect of vitamin E. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1992;81:57–68. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(92)90026-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Knight TR, Bajt ML. The role of oxidant stress and reactive nitrogen species in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2003;144:279–288. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(03)00239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Lemasters JJ. Apoptosis versus oncotic necrosis in hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1246–1257. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, McGill MR, Ramachandran A. Oxidant stress, mitochondria, and cell death mechanisms in drug-induced liver injury: lessons learned from acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Drug Metab. Rev. 2012a;44:88–106. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2011.602688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, McGill MR, Williams CD, Ramachandran A. Current issues with acetaminophen hepatotoxicity-A clinically relevant model to test the efficacy of natural products. Life Sci. 2011a;88:737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Williams CD, Farhood A. No evidence for caspase-dependent apoptosis in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2011b;53:718–719. doi: 10.1002/hep.23940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Williams CD, Ramachandran A, Bajt ML. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and repair: the role of sterile inflammation and innate immunity. Liver Int. 2012b;32:8–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02501.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahr S, Hentze H, Englisch S, Hardt D, Fackelmayer FO, Hesch RD, Knippers R. DNA fragments in the blood plasma of cancer patients: quantitations and evidence for their origin from apoptotic and necrotic cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1659–1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain NK, Singhai AK. Protective effects of Phyllanthus acidus (L.) Skeels leaf extracts on acetaminophen and thioacetamide induced hepatic injuries in Wistar rats. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2011;4:470–474. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LP, Letzig L, Simpson PM, Capparelli E, Roberts DW, Hinson JA, Davern TJ, Lee WM. Pharmacokinetics of acetaminophen-protein adducts in adults with acetaminophen overdose and acute liver failure. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009;37:1779–1784. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.026195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James LP, McCullough SS, Lamps LW, Hinson JA. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on acetaminophen toxicity in mice: relationship to reactive nitrogen and cytokine formation. Toxicol. Sci. 2003;75:458–467. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeannin P, Jaillon S, Delneste Y. Pattern recognition receptors in the immune response against dying cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2008;20:530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jollow DJ, Mitchell JR, Potter WZ, Davis DC, Gillette JR, Brodie BB. Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. II. Role of covalent binding in vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1973;187:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju C, Reilly TP, Bourdi M, Radonovich MF, Brady JN, George JW, Pohl LR. Protective role of Kupffer cells in acetaminophen-induced hepatic injury in mice. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2002;15:1504–1513. doi: 10.1021/tx0255976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JS, Wanibuchi H, Morimura K, Wongpoomchai R, Chusiri Y, Gonzalez FJ, Fukushima S. Role of CYP2E1 in thioacetamide-induced mouse hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008;228:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang KS, Kim ID, Kwon RH, Lee JY, Kang JS, Ha BJ. The effects of fucoidan extracts on CCl(4)-induced liver injury. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2008;31:622–627. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-1203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang KS, Yamabe N, Kim HY, Yokozawa T. Effect of sun ginseng methanol extract on lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in rats. Phytomedicine. 2007;14:840–845. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass GE, Macanas-Pirard P, Lee PC, Hinton RH. The role of apoptosis in acetaminophen-induced injury. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;1010:557–559. doi: 10.1196/annals.1299.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kietzmann T, Jungermann K. Modulation by oxygen of zonal gene expression in liver studied in primary rat hepatocyte cultures. Cell. Biol. Toxicol. 1997;13:243–255. doi: 10.1023/a:1007427206391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight TR, Fariss MW, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Role of lipid peroxidation as a mechanism of liver injury after acetaminophen overdose in mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2003;76:229–236. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight TR, Kurtz A, Bajt ML, Hinson JA, Jaeschke H. Vascular and hepatocellular peroxynitrite formation during acetaminophen toxicity: role of mitochondrial oxidant stress. Toxicol. Sci. 2001;62:212–220. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/62.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight TR, Ho YS, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Peroxynitrite is a critical mediator of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in murine livers: protection by glutathione. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;303:468–475. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.038968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon K, Kim JS, Jaeschke H, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial permeability transition in acetaminophen-induced necrosis and apoptosis of cultured mouse hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2004;40:1170–1179. doi: 10.1002/hep.20437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon K, Kim JS, Uchiyama A, Jaeschke H, Lemasters JJ. Lysosomal iron mobilization and induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in acetaminophen-induced toxicity to mouse hepatocytes. Toxicol. Sci. 2010;117:101–108. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari A, Kakkar P. Lupeol protects against acetaminophen-induced oxidative stress and cell death in rat primary hepatocytes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012;50:1781–1789. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küpeli E, Orhan DD, Yesilada E. Effect of Cistus laurifolius L. leaf extracts and flavonoids on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006;103:455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson AM. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Clin. Liver Dis. 2007;11:525–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, Davern TJ, Lalani E, Hynan LS, Reisch JS, Schiodt FV, Ostapowicz G, Shakil AO, Lee WM. Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2005;42:1364–1372. doi: 10.1002/hep.20948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JA, Farhood A, Hopper RD, Bajt ML, Jaeschke H. The hepatic inflammatory response after acetaminophen overdose: role of neutrophils. Toxicol. Sci. 2000;54:509–516. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/54.2.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JA, Fisher MA, Simmons CA, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Inhibition of Fas receptor (CD95)-induced hepatic caspase activation and apoptosis by acetaminophen in mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1999;156:179–186. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Lee E, Ko YT. Anti-inflammatory effects of a methanol extract from Pulsatilla koreana in lipopolysaccharide-exposed rats. BMB Rep. 2012;45:371–376. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2012.45.6.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Schyschka L, Mühl-Benninghaus R, Neumann J, Hao L, Nussler N, Dooley S, Liu L, Stöckle U, Nussler AK, Ehnert S. Comparative analysis of phase I and II enzyme activities in 5 hepatic cell lines identifies Huh-7 and HCC-T cells with the highest potential to study drug metabolism. Arch. Toxicol. 2012;86:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s00204-011-0733-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Mugundu GM, Kirby BJ, Samineni D, Desai PB, Unadkat JD. Quantification of human hepatocyte cytochrome P450 enzymes and transporters induced by HIV protease inhibitors using newly validated LC-MS/MS cocktail assays and RT-PCR. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2012;33:207–217. doi: 10.1002/bdd.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loguidice A, Boelsterli UA. Acetaminophen overdose-induced liver injury in mice is mediated by peroxynitrite independently of the cyclophilin D-regulated permeability transition. Hepatology. 2011;54:969–978. doi: 10.1002/hep.24464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manov I, Hirsh M, Iancu TC. N-acetylcysteine does not protect HepG2 cells against acetaminophen-induced apoptosis. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2004;94:213–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2004.pto940504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Murphy BV, Holt MP, Ju C. The role of damage associated molecular pattern molecules in acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. Toxicol. Lett. 2010;192:3873–94. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masubuchi Y, Nakayama J, Watanabe Y. Sex difference in susceptibility to acetaminophen hepatotoxicity is reversed by buthionine sulfoximine. Toxicology. 2011;287:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masubuchi Y, Suda C, Horie T. Involvement of mitochondrial permeability transition in acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. J. Hepatol. 2005;42:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews WR, Guido DM, Fisher MA, Jaeschke H. Lipid peroxidation as molecular mechanism of liver cell injury during reperfusion after ischemia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1994;16:763–770. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AM, Roberts DW, Hinson JA, Pumford NR. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Analysis of total covalent binding vs. specific binding to cysteine. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1996;24:1192–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill MR, Sharpe MR, Williams CD, Taha M, Curry SC, Jaeschke H. The mechanism underlying acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in humans and mice involves mitochondrial damage and nuclear DNA fragmentation. J. Clin. Invest. 2012a;122:1574–1583. doi: 10.1172/JCI59755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill MR, Williams CD, Xie Y, Ramachandran A, Jaeschke H. Acetaminophen-induced liver injury in rats and mice: Comparison of protein adducts, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress in the mechanism of toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012b;264:387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill MR, Yan HM, Ramachandran A, Murray GJ, Rollins DE, Jaeschke H. HepaRG cells: A human model to study mechanisms of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2011;53:974–982. doi: 10.1002/hep.24132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean AE, McLean EK. The effect of diet and 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis-(p-chlorophenyl) ethane (DDT) on microsomal hydroxylating enzymes and on sensitivity to carbon tetrachloride poisoning. Biochem. J. 1966;100:564–571. doi: 10.1042/bj1000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JR, Jollow DJ, Potter WZ, Gillette JR, Brodie BB. Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. IV. Protective role of glutathione. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1973;187:211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldrew KL, James LP, Coop L, McCullough SS, Hendrickson HP, Hinson JA, Mayeux PR. Determination of acetaminophen-protein adducts in mouse liver and serum and human serum after hepatotoxic doses of acetaminophen using high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002;30:446–451. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.4.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers TG, Dietz EC, Anderson NL, Khairallah EA, Cohen SD, Nelson SD. A comparative study of mouse liver proteins arylated by reactive metabolites of acetaminophen and its nonhepatotoxic regioisomer, 3′-hydroxyacetanilide. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1995;8:403–413. doi: 10.1021/tx00045a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai H, Matsumaru K, Feng G, Kaplowitz N. Reduced glutathione depletion causes necrosis and sensitization to tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis in cultured mouse hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2002;36:55–64. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa H, Maeda S, Hikiba Y, Ohmae T, Shibata W, Yanai A, Sakamoto K, Ogura K, Noguchi T, Karin M, Ichijo H, Omata M. Deletion of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 attenuates acetaminophen-induced liver injury by inhibiting c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1311–21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SD. Molecular mechanisms of the hepatotoxicity caused by acetaminophen. Semin. Liver Dis. 1990;10:267–278. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni HM, Bockus A, Boggess N, Jaeschke H, Ding WX. Activation of autophagy protects against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Hepatology. 2012;55:222–232. doi: 10.1002/hep.24690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwozo SO, Oyinloye BE. Hepatoprotective effect of aqueous extract of Aframomum melegueta on ethanol-induced toxicity in rats. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2011;58:355–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oz HS, McClain CJ, Nagasawa HT, Ray MB, de Villiers WJ, Chen TS. Diverse antioxidants protect against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2004;18:361–368. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Benet LZ, Burlingame AL. Identification of the hepatic protein targets of reactive metabolites of acetaminophen in vivo in mice using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:17940–17953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Benet LZ, Burlingame AL. Identification of hepatic protein targets of the reactive metabolites of the non-hepatotoxic regioisomer of acetaminophen, 3′-hydroxyacetanilide, in the mouse in vivo using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2001;500:663–673. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0667-6_99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran A, Lebofsky M, Baines CP, Lemasters JJ, Jaeschke H. Cyclophilin D deficiency protects against acetaminophen-induced oxidant stress and liver injury. Free Radic. Res. 2011a;45:156–164. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2010.520319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran A, Lebofsky M, Weinman SA, Jaeschke H. The impact of partial manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2)-deficiency on mitochondrial oxidant stress, DNA fragmentation and liver injury during acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011b;251:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray SD, Sorge CL, Raucy JL, Corcoran GB. Early loss of large genomic DNA in vivo with accumulation of Ca2+ in the nucleus during acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1990;106:346–351. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(90)90254-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remirez D, González R, Rodriguez S, Ancheta O, Bracho JC, Rosado A, Rojas E, Ramos ME. Protective effects of Propolis extract on allyl alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Phytomedicine. 1997;4:309–314. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(97)80038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risal P, Hwang PH, Yun BS, Yi HK, Cho BH, Jang KY, Jeong YJ. Hispidin analogue davallialactone attenuates carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. J. Nat. Prod. 2012 doi: 10.1021/np300099a. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DW, Bucci TJ, Benson RW, Warbritton AR, McRae TA, Pumford NR, Hinson JA. Immunohistochemical localization and quantification of the 3-(cystein-S-yl)-acetaminophen protein adduct in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Am. J. Pathol. 1991;138:359–371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan PM, Bourdi M, Korrapati MC, Proctor WR, Vasquez RA, Yee SB, Quinn TD, Chakraborty M, Pohl LR. Endogenous interleukin-4 regulates glutathione synthesis following acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012;25:83–93. doi: 10.1021/tx2003992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito C, Lemasters JJ, Jaeschke H. c-Jun N-terminal kinase modulates oxidant stress and peroxynitrite formation independent of inducible nitric oxide synthase in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010a;246:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito C, Zwingmann C, Jaeschke H. Novel mechanisms of protection against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in mice by glutathione and N-acetylcysteine. Hepatology. 2010b;51:246–254. doi: 10.1002/hep.23267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen WF, Yang X, Shi Q, Greenhaw J, Davis K, Ali AA. Green tea extract can potentiate acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012;50:1439–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlayer HJ, Laaff H, Peters T, Woort-Menker M, Estler HC, Karck U, Schaefer HE, Decker K. Involvement of tumor necrosis factor in endotoxin-triggered neutrophil adherence to sinusoidal endothelial cells of mouse liver and its modulation in acute phase. J. Hepatol. 1988;7:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(88)80488-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sener G, Omurtag GZ, Sehirli O, Tozan A, Yüksel M, Ercan F, Gedik N. Protective effects of ginkgo biloba against acetaminophen-induced toxicity in mice. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2006;283:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-2268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevior DK, Hokkanen J, Tolonen A, Abass K, Tursas L, Pelkonen O, Ahokas JT. Rapid screening of commercially available herbal products for the inhibition of major human hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes using the N-in-one cocktail. Xenobiotica. 2010;40:245–254. doi: 10.3109/00498251003592683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Singh RL, Kakkar P. Modulation of Bax/Bcl-2 and caspases by probiotics during acetaminophen induced apoptosis in primary hepatocytes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011;49:770–779. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Kamendulis LM, Ray SD, Corcoran GB. Acetaminophen-induced cytotoxicity in cultured mouse hepatocytes: effects of Ca(2+)-endonuclease, DNA repair, and glutathione depletion inhibitors on DNA fragmentation and cell death. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1992;112:32–40. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90276-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CV, Jaeschke H. Effect of acetaminophen on hepatic content and biliary efflux of glutathione disulfide in mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1989;70:241–248. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(89)90047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirmenstein MA, Nelson SD. Subcellular binding and effects on calcium homeostasis produced by acetaminophen and a nonhepatotoxic regioisomer, 3′-hydroxyacetanilide, in mouse liver. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:9814–9819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toklu HZ, Sehirli AO, Velioğlu-Oğünç A, Cetinel S, Sener G. Acetaminophen-induced toxicity is prevented by beta-D-glucan treatment in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006;543:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng JI, Chen MF, Chung HH, Cheng JT. Silymarin decreases connective tissue growth factor to improve liver fibrosis in rats treated with carbon tetrachloride. Phytother. Res. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ptr.4829. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y, Wu YL, Lian LH, Nan JX. Protective effect of Ornithogalum saundersiae Ait (Liliaceae) against acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury via CYP2E1 and HIF-1α. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2012;10:177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Wang JH, Shin JW, Choi MK, Kim HG, Son CG. An herbal fruit, Amomum xanthoides, ameliorates thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis in rat via antioxidative system. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;135:344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Zhu P, Jiang C, Ma L, Zhang Z, Zeng X. Preliminary characterization, antioxidant activity in vitro and hepatoprotective effect on acute alcohol-induced liver injury in mice of polysaccharides from the peduncles of Hovenia dulcis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012;50:2964–2970. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weddle CC, Hornbrook KR, McCay PB. Lipid peroxidation and alteration of membrane lipids in isolated hepatocutes exposed to carbon tetrachloride. J. Biol. Chem. 1976;251:4973–4978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel A, Feuerstein S. Drug-induced lipid peroxidation in mice--I. Modulation by monooxygenase activity, glutathione and selenium status. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1981;30:2513–2520. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(81)90576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel A, Feuerstein S, Konz KH. Acute paracetamol intoxication of starved mice leads to lipid peroxidation in vivo. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1979;28:2051–2055. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]