Abstract

Obesity has been associated with a higher risk of mortality, whereas caloric restriction reduces the risk. In this study, we examined how body weight development during life affects lifespan in a mouse model for obesity. Therefore, mice of the Berlin Fat Mouse Inbred line were set on either a standard or a high-fat diet (HFD). Median lifespans of standard diet-fed mice were 525 and 539 days for males and female animals, respectively. HFD feeding further decreased lifespan by increasing the risk of mortality. Our data provide evidence that the highest body weight reached in lifetime has only a minor effect on lifespan. More important is the age when the highest body weight is reached, which was positively correlated with lifespan (r=0.77, P<0.0001). Likewise, the daily gain of body weight was negatively correlated with the age of death (r=−0.76, P<0.0001). These data indicate that rapid weight gain in early life followed by rapid weight loss affect lifespan more than the body weight itself. These data suggest that intervention strategies to prevent rapid weight gain are of high impact for a long lifespan.

Keywords: adiposity, body weight development, epidemiology, longevity, polygenic mouse model, survival

Introduction

Studies have shown that obesity and body fat are positively associated with a higher mortality rate.1, 2 In the other direction, caloric restriction and reduction in food intake without malnutrition extends the lifespans of diverse organisms.3 Furthermore, life expectancy also depends on the genetic background.4, 5 Experiments in rodents suggest that the effect of caloric restriction on longevity is independent of body weight.4, 6

The aim of this study was to investigate how body weight development during life affects the lifespan in a genetically obese mouse model. We investigated body weight changes during lifetime and the influence of different diets on life expectancy. As a model, we used the Berlin Fat Mouse Inbred line 860 (BFMI860). BFMI860 mice are obese as a result of repeated selection for fatness over >90 generations before they were inbred. These mice harbour natural mutations causing a higher fat percentage already during adolescence. As shown in previous studies, BFMI860 mice were 1.8-times as heavy as the often used C57BL/6NCrl animals and had almost 10-times as much total body fat mass, but only 1.5-times as much lean mass at the age of 10 weeks. The juvenile obesity is due to hyperphagia and an altered lipid metabolism, and is accompanied by dislipidemia and hyperinsulinemia.7, 8, 9, 10, 11

Materials and methods

Animals

We used the BFMI860/Hber mouse line in this study. The breeding history is outlined in detail in the study of Wagener et al.8 In brief, the BFMI860/Hber line was generated as one of several inbred lines from the outbred population BFM. Founders of this outbred population were originally purchased from pet shops, and subsequently selected firstly for low protein content, secondly for low body mass and high fat content and then for high fatness, before inbreeding. After weaning at the age of 3 weeks, 22 male and 9 female animals of the BFMI860 inbred line were randomly chosen and fed either a standard maintenance diet with 12.8 MJ kg−1 energy or a high-fat diet (HFD) with 19.1 MJ kg−1 energy (V1534-000 ssniff R/M-H and S8074-E010 ssniff EF R/M, ssniff Spezialdiäten GmbH, Soest, Germany). Animals were housed two per cage and had ad-libitum access to water and diet. Weekly, the cages and bedding were changed, and the animals were weighed. To determine daily weight gain until reaching the highest body weight, the difference between the body weight at 3 weeks and the highest body weight was divided by the number of days between 3 weeks and the age when the highest body weight was reached. The daily loss of body weight was calculated as the difference between the highest body weight and the weight at death, divided by the number of days from the day of the highest body weight to the day of death. To determine the day of death, old mice were inspected daily. Mice were euthanized if they were severely ill. A mouse was considered severely ill if it was unable to eat or drink, showed severe balance disturbance, rapid weight loss (>20% within 1 week) or visible tumours. All animal treatments were in accordance with the German Animal Welfare Legislation (approval no. G0301/08).

Statistical data analyses

Analysis of variance was performed to evaluate the effects of sex and diet using SAS 9.3 statistical software package (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). T-test was performed to compare differences between groups. For the analysis of body weight development, a random regression model was used, which includes sex, diet, age and age squared as fixed effects, a random intercept and a random age slope for each animal. As the interaction was not significant, it was dropped from following analyses. Estimated growth curves were based on the estimated values for the fixed effects and were calculated using PROC MIXED. The time-dependent variable lifespan was analysed by a Cox regression model using PROC PHREG, including sex and diet as independent variables. The PHREG procedure performs regression analysis of survival data based on the Cox proportional hazards model. The time dependence of resulting hazards was proofed and could be negated. Pearson's correlation coefficients were used to access the relationships between measurements. To increase the statistical power, correlation analyses were performed with least square means across all groups after adjustment for sex and diet. Data in Table 1 are presented as raw data for clarity.

Table 1. Body weight development during life and median lifespan of BFMI mice.

|

Males |

Females |

Effects of: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard diet | High-fat diet | Standard diet | High-fat diet | Sex | Diet | |

| Number of animals | 9 | 13 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Body weight at 10 weeks (g) | 42.58 (2.5)a,b | 51.43 (2.5)a | 36.17 (2.2)b | 46.46 (4.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Highest body weight in life (g) | 56.76 (4.8) | 71.37 (5.6)b | 52.32 (4.1) | 62.61 (13.5) | 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Body weight on the last day (g) | 31.73 (8.4) | 39.40 (16.7) | 39.28 (10.8) | 48.15 (14.4) | ns | ns |

| Daily gain of body weightc | 0.17 (0.08) | 0.22 (0.10) | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.33 (0.18) | ns | 0.01 |

| Daily loss of body weightd | −0.23 (0.19) | −0.33 (0.19) | −0.09 (0.02) | −0.14 (0.09) | 0.01 | ns |

| Median lifespan | 525 (0.31) | 399 (0.36) | 539 (0.30) | 294 (0.61) | ns | 0.05 |

Abbreviation: ns, not significant.

Values of body weights are in means with s.d. in parentheses. Lifespan is given as median with coefficient of variance in parentheses.

Indicates significant differences between sexes within each diet group (P<0.05).

Indicates significant differences between standard and high-fat diet within each sex (P<0.05).

Until the age of maximal body weight in life.

After the age of maximal body weight in life.

Results

The effects of sex and diet on long-term body weight development

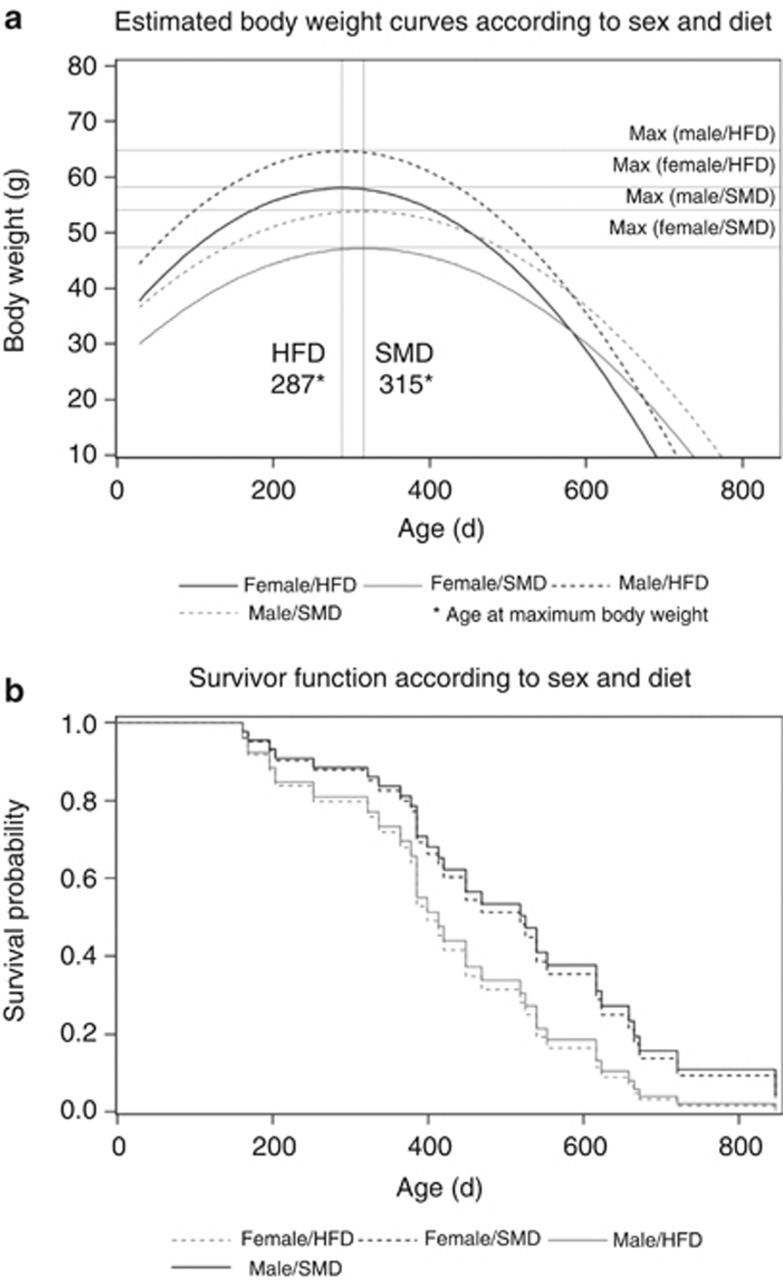

As previously shown, BFMI860 mice developed a marked obesity with the greatest gain of body weight within the growth phase until 10 weeks, with male mice being heavier than the female ones (Table 1). On HFD, obesity was even more pronounced. Throughout the lifespan, male and female mice gained additional 33–45% of the 10-week body weight on both diets. The estimated development of body weight throughout life showed a gain until a turning point at 315 days in standard diet-fed mice and at 287 days in HFD-fed mice (Figure 1a). Subsequently, mice of both diets showed a slow body weight loss before death until a body weight was reached that was comparable or even below that at 10 weeks (Table 1). Altogether, the estimated growth curves showed a more intensive body weight gain, followed by steeper body weight decline in high-fat mice compared with that in standard diet-fed mice (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Estimated growth curves (a) and estimated survival probabilities (b) for male (dotted line) and female (continuous line) BFMI860 mice fed either a standard (grey) or HFD (black). SMD, standard maintenance diet. HFD, high-fat diet.

The effects of sex and diet on lifespan

Although male and female mice had different body weights throughout life, these differences did not significantly affect lifespan. For both sexes, median lifespan was about 532 days on standard diet. On HFD, median lifespan was reduced by 126 and 245 days in male and female mice, respectively (Table 1). The analyses of survival probabilities revealed no effects for sex but a small effect for diet (P=0.10). As shown in Figure 1b, the estimated survival probabilities were similar in both sexes on each diet, whereas the survival probabilities of both sexes were reduced after prolonged HFD feeding (Figure 1b). The hazard ratio of the diet was 1.73, indicating an increased risk of mortality as a result of HFD feeding.

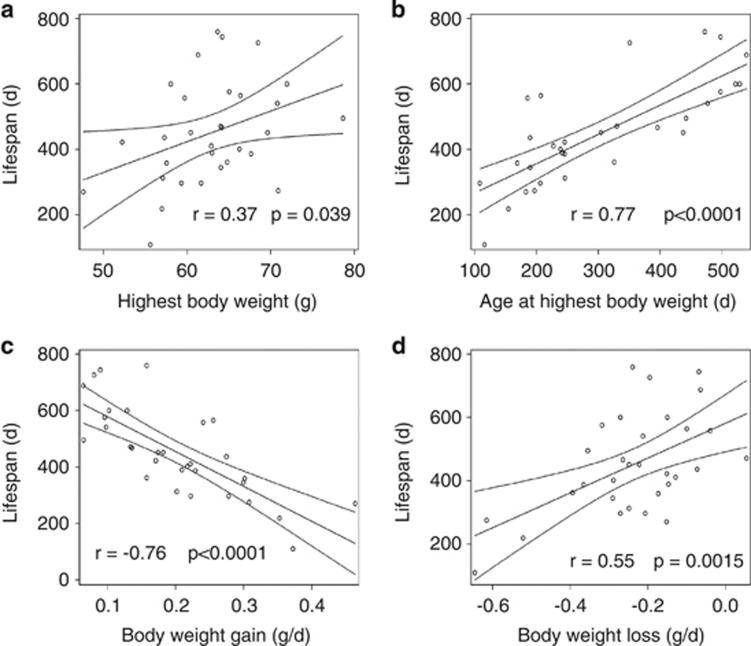

Determinants of lifespan

As HFD feeding led to an earlier death compared with that in standard diet-fed mice, the highest body weight reached in lifetime, the daily gain of body weight or the age of highest body weight could be possible factors influencing the lifespan. To find the relationship between those factors, correlation analyses were performed. The highest body weight reached in lifetime was only slightly positively correlated with lifespan (r=0.37, P=0.0397) (Figure 2). In contrast, there was a strong positive correlation between the age, when highest body weight was reached, and lifespan (r=0.77, P<0.0001). Accordingly, the daily gain of body weight in the phase until reaching the highest body weight was negatively correlated with the age of death (r=−0.76, P<0.0001). Likewise, the daily loss of body weight before death was positively correlated with the age of death (r=0.55, P=0.0015).

Figure 2.

Relationship between lifespan and (a) highest body weight, (b) age at highest body weight, (c) daily body weight gain and (d) body weight loss. Correlation coefficient with regression lines and 95% confidence interval for mean predicted values are given.

Discussion

Compared with many other mouse lines with a median lifespan of about 800 days,12 BFMI860 mice showed a relatively short lifespan, which is consistent with other models for obesity and diabetes, like the NZO mouse. After HFD, a further reduction of median lifespan and an increased risk of mortality could be shown in our study. Although HFD-fed mice had higher body weights than standard diet-fed mice, our data provide evidence that body weight itself only marginally affects lifespan. The results obtained in this study suggest that, in particular, the age when body weight reaches the maximum, and the intensity of weight gain in the early development and weight loss after body weight has reached a maximum have an influence on longevity. The faster the mice gain weight, the earlier they reach their highest weight in life and the higher the loss of weight afterwards, the earlier they die. However, specific age-associated pathologies that might have contributed to mortality due to faster weight gain could not be observed in this study. Our data support findings of epidemiological studies in humans, where a high BMI in young men and women was associated with decreased life expectancy, whereas a high BMI at higher ages is associated with increased survival.2

It has been repeatedly suggested that high IGF-1 levels contribute to shortening life expectancy.3, 12 The almost two-times as high IGF-1 levels in BFMI860 mice13 compared with other mice might contribute to the shorter lifespan compared with other mouse lines. In a feeding experiment, IGF-1 levels did not differ between BFMI860 mice fed either a standard or HFD until the age of 10 weeks.13 Therefore, we would assume that IGF-1 does not contribute to the observed diet differences on ageing in BFMI860 mice. However, we cannot exclude that mice differ in serum IGF-1 levels at a later age, which could contribute to aging then.

In summary, obese BFMI860 mice showed a relatively low lifespan under standard diet conditions, which was further decreased by HFD feeding that increased the risk of mortality. The age when the highest body weight is reached and daily weight gain affect lifespan, rather than the body weight itself. These data suggests that intervention strategies to prevent rapid weight gain are of high importance for a long lifespan. Albeit this is a first study with a limited number of animals, the data provide interesting results and have provocative implications for human medicine whereby slow, low and steady weight gain during adulthood and old age may predict a long life.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the German National Genome Research Network (NGFN: 01GS0829).

Author contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:891–898. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis JP, Macera CA, Araneta MR, Lindsay SP, Marshall SJ, Wingard DL. Comparison of overall obesity and body fat distribution in predicting risk of mortality. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1232–1239. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span--from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328:321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao CY, Rikke BA, Johnson TE, Diaz V, Nelson JF. Genetic variation in the murine lifespan response to dietary restriction: from life extension to life shortening. Aging Cell. 2010;9:92–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner J, Weber D, Neuschl C, Franke A, Bottger M, Zielke L, et al. Mapping of quantitative trait loci controlling lifespan in the short-lived fish Nothobranchius furzeri—a new vertebrate model for age research. Aging Cell. 2012;11:252–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00780.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Weindruch R, Fernandez JR, Coffey CS, Patel P, Allison DB. Caloric restriction and body weight independently affect longevity in Wistar rats. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:357–362. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer CW, Wagener A, Rink N, Hantschel C, Heldmaier G, Klingenspor M, et al. High energy digestion efficiency and altered lipid metabolism contribute to obesity in BFMI860 mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1988–1993. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagener A, Schmitt AO, Aksu S, Schlote W, Neuschl C, Brockmann GA. Genetic, sex, and diet effects on body weight and obesity in the Berlin Fat Mouse Inbred lines. Physiol Genomics. 2006;27:264–270. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00225.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuschl C, Hantschel C, Wagener A, Schmitt AO, Illig T, Brockmann GA. A unique genetic defect on chromosome 3 is responsible for juvenile obesity in the Berlin Fat Mouse. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:1706–1714. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantschel C, Wagener A, Neuschl C, Teupser D, Brockmann GA. Features of the metabolic syndrome in the Berlin Fat Mouse as a model for human obesity. Obes Facts. 2011;4:270–277. doi: 10.1159/000330819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagener A, Goessling HF, Schmitt AO, Mauel S, Gruber AD, Reinhardt R, et al. Genetic and diet effects on Ppar-α and Ppar-γ signaling pathways in the Berlin Fat Mouse Inbred line with genetic predisposition for obesity. Lipids Health Dis. 2010;9:99. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-9-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan R, Tsaih SW, Petkova SB, Marin de Evsikova C, Xing S, Marion MA, et al. Aging in inbred strains of mice: study design and interim report on median lifespans and circulating IGF1 levels. Aging Cell. 2009;8:277–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer N, Wagener A, Hantschel C, Mauel S, Gruber AD, Brockmann GA. IGF-I contributes to glucose homeostasis in the Berlin Fat Mouse Inbred line. Growth Factors. 2011;29:298–309. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2011.625026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]