Abstract

The shikimate pathway provides carbon skeletons for the aromatic amino acids l-tryptophan, l-phenylalanine, and l-tyrosine. It is a high flux bearing pathway and it has been estimated that greater than 30% of all fixed carbon is directed through this pathway. These combined pathways have been subjected to considerable research attention due to the fact that mammals are unable to synthesize these amino acids and the fact that one of the enzymes of the shikimate pathway is a very effective herbicide target. However, in addition to these characteristics these pathways additionally provide important precursors for a wide range of important secondary metabolites including chlorogenic acid, alkaloids, glucosinolates, auxin, tannins, suberin, lignin and lignan, tocopherols, and betalains. Here we review the shikimate pathway of the green lineage and compare and contrast its evolution and ubiquity with that of the more specialized phenylpropanoid metabolism which this essential pathway fuels.

Keywords: shikimate pathway, aromatic amino biosynthesis, evolution, gene copy number, gene duplication, plant secondary phenolic metabolite

Introduction

The shikimate pathway is closely interlinked with those of the aromatic amino acids (L-tryptophan, l-phenylalanine, and L-tyrosine) and in land plants bears very high fluxes with estimates of the amount of fixed carbon passing through the pathway varying between 20 and 50% (Weiss, 1986; Corea et al., 2012; Maeda and Dudareva, 2012). Considerable research focus has been placed on this pathway since the aromatic amino acids are not produced by humans and monogastric livestock and are therefore an important dietary component (Tzin and Galili, 2010). Furthermore, one of the enzymes of the pathway – 5-enolpyruvalshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSP) – is one of the most widely employed herbicide target sites (see, Duke and Powles, 2008). Moreover, as we have recently described, plant phenolic secondary metabolites and their precursors are synthesized via the pathway of shikimate biosynthesis and its numerous branchpoints (Tohge et al., 2013). The shikimate pathway is highly conserved being found in fungi, bacteria, and plant species wherein it operates in the biosynthesis of not just the three aromatic amino acids described above but also of innumerable aromatic secondary metabolites such as alkaloids, flavonoids, lignins, and aromatic antibiotics. Many of these compounds are bioactive as well as playing important roles in plant defense against biotic and abiotic stresses and environmental interactions (Hamberger et al., 2006; Maeda and Dudareva, 2012), and as such are highly physiologically important. It is estimated that under normal conditions as much as 20% of the total fixed carbon flows through to shikimate pathway (Ni et al., 1996), with greater carbon flow through the pathway under times of plant stress or rapid growth (Corea et al., 2012). Given its importance it is perhaps not surprising that all members of biosynthetic genes and corresponding enzymes involved in shikimate pathway have been characterized in model plants such as Arabidopsis. Cross-species comparison of the shikimate biosynthetic enzymes has revealed that they share sequence similarity, divergent evolution, and commonality in reaction mechanisms (Dosselaere and Vanderleyden, 2001). However, all other species vary considerably from fungi which has evolved a complex system with a single pentafunctional polypeptide known as the AroM complex which performs five consecutive reactions (Lumsden and Coggins, 1977; Duncan et al., 1987). In this review we will summarize current knowledge concerning the genetic nature of this pathway focusing on cross-species comparisons bridging a wide range of species including algae (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Volvox carteri, Micromonas sp., Ostreococcus tauri, Ostreococcus lucimarinus), moss (Selaginella moellendorffii, Physcomitrella patens), monocots (Sorghum bicolor, Zea mays, Brachypodium distachyon, Oryza sativa ssp. japonica and Oryza sativa ssp. indica), and dicots (Vitis vinifera, Theobroma cacao, Carica papaya, Arabidopsis thaliana, Arabidopsis lyrata, Populus trichocarpa, Ricinus communis, Manihot esculenta, Malus domestica, Fragaria vesca, Glycine max, Lotus japonicus, Medicago truncatula) species (Table 1). Finally, we compare and contrast the evolution of this pathway with that of the more specialized pathways of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis.

Table 1.

Summary of the species used in the study.

| Species name | ID | Common name | Classification | Species | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | CR | Green algae | Chlorophyte | Chlamydomonadaceae |

| 2 | Volvox carteri | VC | Algae | Chlorophyte | Volvoceae |

| 3 | Micromonas sp. RCC299 | MRC | Micromonas | Chlorophyta | Prasinophyceae |

| 4 | Ostreococcus tauri | OT | Microalgae | Prasinophyte | Prasinophyceae |

| 5 | Ostreococcus lucimarinus | OL | Microalgae | Prasinophyte | Prasinophyceae |

| 6 | Selaginella moellendorffii | SM | Spike moss | Lycophytes | Selaginellaceae |

| 7 | Physcomitrella patens | PP | Moss | Lycophytes | Funariaceae |

| 8 | Sorghum bicolor | SB | Sorghum | Monocot | Poaceae |

| 9 | Zea mays | ZM | Corn | Monocot | Poaceae |

| 10 | Brachypodium distachyon | BD | Purple false brome | Monocot | Poaceae |

| 11 | Oryza sativa ssp. japonica | OS | Japonica rice | Monocot | Poaceae |

| 12 | Oryza sativa ssp. indica | OSI | Indica rice | Monocot | Poaceae |

| 13 | Vitis vinifera | VV | Grapevine | Dicot | Vitaceae |

| 14 | Theobroma cacao | TC | Cacao | Dicot | Malvaceae |

| 15 | Carica papaya | CP | Papaya | Dicot | Caricaceae |

| 16 | Arabidopsis thaliana | AT | Arabidopsis | Dicot | Brassicaceae |

| 17 | Arabidopsis lyrata | AL | Lyrata | Dicot | Brassicaceae |

| 18 | Populus trichocarpa | PT | Poplar | Dicot | Salicaceae |

| 19 | Ricinus communis | RC | Castor oil plant | Dicot | Euphorbiaceae |

| 20 | Manihot esculenta | ME | Cassava | Dicot | Euphorbiaceae |

| 21 | Malus domestica | MD | Apple | Dicot | Rosaceae |

| 22 | Fragaria vesca | FV | Strawberry | Dicot | Rosaceae |

| 23 | Glycine max | GM | Soybean | Dicot | Fabaceae |

| 24 | Lotus japonicus | LJ | Lotus | Dicot | Fabaceae |

| 25 | Medicago truncatula | MT | Medicago | Dicot | Fabaceae |

Coding genes is estimated by Plaza (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/plaza/). Relationships among the species considered are presented on the Plaza website (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/plaza/).

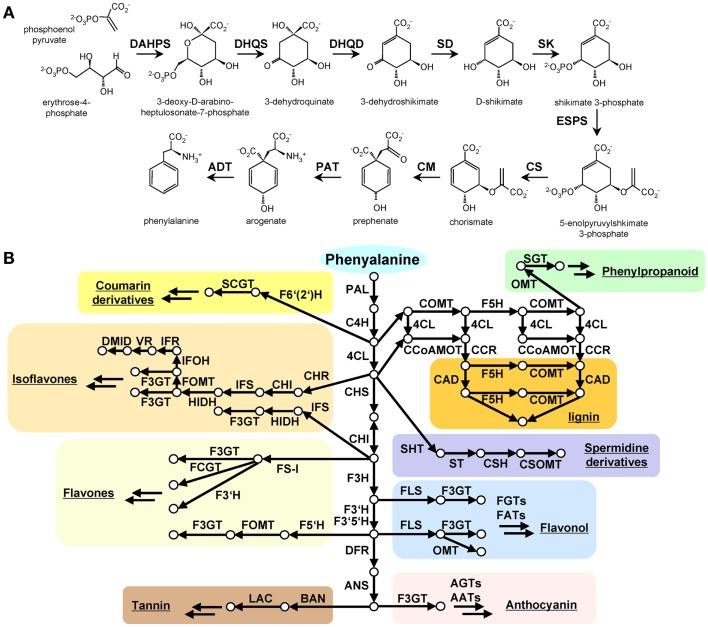

Shikimate Biosynthesis and Phenylalanine Derived Secondary Metabolism in Plants

Given that phenolic secondary metabolites which are derived from phenylalanine via shikimate biosynthesis are widely distributed in plants and other eukaryotes, genes encoding shikimate biosynthetic enzymes are generally highly conserved in nature. Eight and two reactions are involved in shikimate and phenylalanine biosynthesis, respectively. Both members of all gene families and the corresponding biosynthetic enzymes involved in these pathways have been characterized in model plants such as Arabidopsis (Figure 1A). In contrast, phenolic secondary metabolites derived from phenylalanine display considerable species-specific distribution with the phenolic secondary metabolites have been found in plant kingdom such as coumarin derivatives, monolignal, lignin, spermidin derivatives, flavonoid, tannin being present in specific families within the green lineage (Figure 1B). This diversity has arisen by the action of diverse evolutionary strategies for example gene duplication and cis-regulatory evolution in order to adapt to prevailing environmental conditions. Given their species-specific distribution, the genes involved in plant phenolic secondary metabolism such as phenylammonia-lyase (PAL), polyketide synthase (PKS), 2-oxoglutarate-dependent deoxygenases (2ODDs), and UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs) are frequently used as case studies of plant evolution (Tohge et al., 2013). Despite the fact that shikimate-phenylalanine biosynthetic genes are well conserved in all species including algae species, phenolic secondary metabolism related orthologous genes were not detected in all algae species (Table 2, Tohge et al., 2013). This result suggests a considerably more ancient origin of the shikimate-phenylalanine pathways. In the next sections, we will discuss the evolution of shikimate-phenylalanine pathways focusing on cross-species comparisons for each gene encoding on of the constituent enzymes of either pathway.

Figure 1.

The shikimate and phenylalanine derived secondary metabolite biosynthesis in plants. (A) Shikimate biosynthesis starting from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and D-erythrose 4-phosphate is described with characterized genes and reported intermediate metabolites. (B) phenylalanine derived major phenolic secondary mebolite biosynthesis in the green lineage. Arrow indicates enzymatic reaction, circle indicates metabolite. Abbreviation: DAHPS, 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase; DQS, 3-dehydroquinate synthase; DHQD/SD, 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase; SK, shikimate kinase; ESPS, 3-phosphoshikimate 1-carboxyvinyltransferase; CS, chorismate synthase; CM, chorismate mutase; PAT, prephenate aminotransferase; ADT, arogenate dehydratase. PAL, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase; C4H, cinnamate-4-hydroxylase; 4CL, 4-coumarate CoA ligase; CAD, cinnamoyl-alcohol dehydrogenase; F5H, ferulate 5-hydroxylase; C3H, coumarate 3-hydroxylase; ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; CCR, cinnamoyl-CoA reductase; HCT, hydroxycinnamoyl-Coenzyme A shikimate/quinate hydroxycinnamoyltransferase; CCoAOMT, caffeoyl/CoA-3-O-metheltransferase; CHS, chalcone synthese; CHI, chalcone isomerase; F3H, flavanone 3-hydroxylase; F3′H, flavonoid-3′-hydroxylase; F3GT, flavonoid-3-O-glycosyltransferase; FS, flavone synthase; FOMT, flavonoid O-methyltransferase; FCGT, flavone-C-glycosyltransferase; FLS, flavonol synthese; F3GT, flavonoid-3-O-glycosyltransferase; DFR, dihydroflavonol reductase; ANS, Anthocyanidin synthese; AGT, Flavonoid-O-glycosyltransferase; AAT, anthocyanin acyltransferase; BAN, oxidoreductase|dihydroflavonol reductase like; LAC, laccase.

Table 2.

Shikimate and phenylalanine biosynthetic genes and homologs in each species with/without tandem duplicated genes.

| No. ID | 1 CR | 3 MRCC299 | 4 OT | 8 SB | 9 ZM | 10 BD | 11 OS | 12 OSindica |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHS | Cr17g06460 | Mrcc02g07760 | Ot06g03510 | Sb01g028770 | Zm02g39200 | Bd1g21330 | Os03g27230 | Osi07g35030 |

| Sb01G033590 | Zm04g31550 | Bd1g60750 | Os07g42960 | Osi08g36090 | ||||

| Sb02G039660 | Zm05g06990 | Bd3g33650 | Os08g37790 | Osi10g31830 | ||||

| Sb07G029080 | Bd3g38670 | Os10g41480 | ||||||

| DQS | Cr08g02240 | Mrcc01g05190 | Ot05g01830 | Sb02G031240 | Zm02g34320 | Bd4g36507 | Os09g36800 | Osi09g29080 |

| DHQD | Cr08g04550 | Mrcc01g03580 | Ot12g02660 | Sb08G016970 | Zm03g17940 | Bd4g05897 | Os12g34874 | Osi12g23310 |

| Zm10g05140 | ||||||||

| SK | Cr10g04010 | Mrcc13g02500 | Ot14g03180 | Sb06G030260 | Zm02g02970 | Bd3g59237 | Os04g54800 | Osi02g49680 |

| Zm04g27840 | Bd5g23460 | |||||||

| Zm05g40530 | ||||||||

| SKL1 | Sb08G018630 | Zm01g26660 | Bd2g03680 | Os01g01302 | ||||

| SKL2 | Mrcc02g03490 | Ot07g01450 | Sb01G027930 | Zm01g22640 | Bd3g34245 | Os10g42700 | ||

| ESPS | Cr03g06830 | Mrcc13g01100 | Ot14g02430 | Sb10G002230 | Zm09g05500 | Bd1g51660 | Os06g04280 | Osi06g03190 |

| CS | Cr01g12390 | Mrcc05g01430 | Ot02g06020 | Sb01G040790 | Zm01g10020 | Bd1g67790 | Os03g14990 | Osi03g13340 |

| Zm09g24540 | ||||||||

| CM | Cr03g01600 | Mrcc08g05060 | Ot08g02860 | Sb03G035460 | Zm03g31000 | Bd2g50800 | Os01g55870 | Osi01g52850 |

| Sb04G005480 | Zm05g21270 | Bd3g06050 | Os02g08410 | Osi02g08160 | ||||

| Zm08g34320 | Os12g38900 | |||||||

| Zm08g34330 | ||||||||

| PAT | Cr02g15900 | Mrcc06g00860 | Ot16g00690 | Sb03G041180 | Zm03g25600 | Bd2g24300 | Os01g65090 | Osi01g61700 |

| Sb09G021360 | Zm08g15210 | Bd2g56330 | ||||||

| ADT | Cr06g02760 | Mrcc01g05870 | Ot01g01250 | Sb01G038740 | Zm01g12020 | Bd5g09020 | Os04g33390 | Osi03g16350 |

| Sb06G015310 | Zm02g16320 | Bd5g09030 | Os03g17730 | Osi04g25440 | ||||

| Zm10g16000 | Bd1g16517 | Os07g49390 | Osi07g41390 | |||||

| Bd1g65800 | ||||||||

| No. ID | 13 VV | 14 TC | 16 AT | 17 AL | 18 PT | 21 MD | 22 FV | 23 GM | 24 LJ | 25 MT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHS | Vv00g09200 | Tc01g008590 | At1g22410 | Al1g23930 | Pt01g14860 | Md00g000730 | Fv0g22320 | Gm02g37080 | Lj1g002520 | Mt2g009080 |

| Vv00g17890 | Tc01g012940 | At4g33510 | Al7g02250 | Pt02g09760 | Md00g361080 | Fv5g19610 | Gm06g10670 | Mt5g064500 | ||

| Vv18g03830 | Tc02g011250 | At4g39980 | Al7g07720 | Pt05g07260 | Md01g001320 | Gm14g35370 | ||||

| Tc03g024120 | Pt05g16320 | Md04g002280 | Gm15g06020 | |||||||

| Tc08g008780 | Pt07g04970 | Md05g021570 | ||||||||

| Md05g025390 | ||||||||||

| Md10g003880 | ||||||||||

| Md11g021260 | ||||||||||

| DQS | Vv04g00350 | Tc01g001360 | At5g66120 | Al8g34560 | Pt05g11110 | Md00g089850 | Fv1g13270 | Gm01g36890 | Lj2g022420 | Mt5g022580 |

| Gm11g08350 | ||||||||||

| DHQD | Vv05g03610 | Tc04g027300 | At3g06350 | Al3g06450 | Pt10g01690 | Md00g196450 | Fv1g19500 | Gm01g20760 | Lj4g005930 | Mt4g090620 |

| Vv14g04450 | Tc05g024340 | Pt13g02880 | Md00g199470 | Fv6g07230 | Gm20g37400 | |||||

| Vv14g04460 | Tc05g024370 | Md00g208810 | Fv6g07240 | |||||||

| Md01g014110 | ||||||||||

| Md01g014130 | ||||||||||

| Md04g017400 | ||||||||||

| Md15g026460 | ||||||||||

| SK | Vv00g22160 | Tc01g010070 | At2g21940 | Al4g01190 | Pt02g06000 | Md00g396950 | Fv6g01580 | Gm04g39700 | Lj1g014890 | |

| Vv07g06350 | At4g39540 | Al7g01530 | Pt05g08460 | Md02g009820 | Gm04g39710 | |||||

| Pt07g06400 | Gm05g31730 | |||||||||

| Gm08g14980 | ||||||||||

| SKL1 | Vv14g14000 | Tc04g004710 | At3g26900 | Al5g05650 | Pt17g08780 | Fv6g51520 | Gm02g08050 | Lj1g008480 | ||

| Gm16g27060 | ||||||||||

| SKL2 | Vv02g01940 | Tc03g029930 | At2g35500 | Al4g20870 | Pt03g08570 | Md00g061570 | Fv0g29740 | Gm01g01890 | Lj3g020970 | Mt1g009450 |

| Md00g432830 | Fv2g18080 | Lj3g020980 | Mt5g029550 | |||||||

| Md06g002680 | ||||||||||

| ESPS | Vv15g09330 | Tc01g037810 | At1g48860 | Al1g42610 | Pt02g14550 | Md00g030870 | Fv7g11420 | Gm01g33660 | Lj3g025840 | Mt4g024620 |

| Vv15g09350 | At2g45300 | Al4g33160 | Pt14g06200 | Md00g271560 | Gm03g03190 | |||||

| CS | Vv06g05280 | Tc10g005370 | At1g48850 | Al1g42550 | Pt08g03850 | Md00g355380 | Fv4g18660 | Gm10g35560 | Lj0g038950 | Mt1g095160 |

| Vv13g03240 | Al3g19880 | Pt10g21700 | Md01g008950 | Fv4g18670 | Gm20g31980 | Lj0g284550 | Mt1g095240 | |||

| Md08g005430 | Fv7g23950 | Mt1g095250 | ||||||||

| Fv7g24040 | ||||||||||

| CM | Vv01g02110 | Tc02g032570 | At1g69370 | Al2g17620 | Pt10g15830 | Md00g250450 | Fv0g04690 | Gm13g05830 | Lj5g005890 | Mt1g013820 |

| Vv04g13080 | Tc04g009770 | At3g29200 | Al5g08750 | Pt17g12090 | Md00g329990 | Fv2g52320 | Gm14g11870 | Lj5g005900 | Mt5g043210 | |

| Vv14g02700 | Tc09g001490 | At5g10870 | Al6g10610 | Pt18g02330 | Md01g020010 | Fv6g43680 | Gm17g33940 | |||

| Md16g003330 | Gm19g03290 | |||||||||

| Md17g004580 | ||||||||||

| PAT | Vv07g05790 | Tc01g009420 | At2g22250 | Al4g01710 | Pt05g07910 | Md00g135490 | Fv6g00440 | Gm05g31490 | Lj6g003720 | Mt8g091280 |

| Vv18g03130 | Pt07g05690 | Md00g246930 | Gm08g14720 | |||||||

| Md00g304630 | Gm11g36190 | |||||||||

| Gm11g36200 | ||||||||||

| ADT | Vv06g04790 | Tc02g034990 | At1g08250 | Al1g12100 | Pt00g13690 | Md00g099570 | Fv3g01120 | Gm11g15750 | Lj3g029800 | Mt2g088130 |

| Vv10g00970 | Tc06g019290 | At1g11790 | Al3g08080 | Pt04g01150 | Md00g099580 | Fv3g16180 | Gm11g19430 | Lj4g001780 | Mt4g055310 | |

| Vv12g10860 | Tc09g026620 | At2g27820 | Al4g12300 | Pt04g18820 | Md00g456520 | Fv3g29940 | Gm12g07720 | Mt4g061070 | ||

| Tc09g028840 | At3g07630 | Al5g12520 | Pt08g19820 | Md05g001400 | Gm12g09050 | Mt4g132250 | ||||

| At3g44720 | Al6g22310 | Pt09g14910 | Md15g019040 | Gm12g30660 | ||||||

| At5g22630 | Gm12g31940 | |||||||||

| Gm17g01610 | ||||||||||

Orthologous genes were estimated by BLAST search in Plaza website. Bold indicates tandem gene duplication.

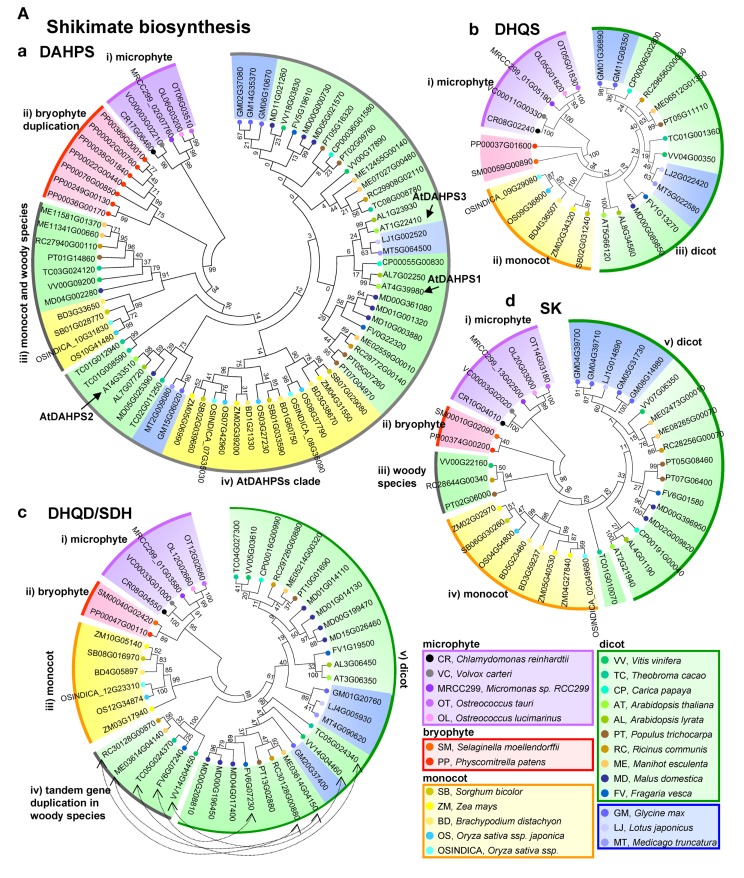

3-Deoxy-D-Arabino-Heptulosonate 7-Phosphate Synthase

The first enzymatic step of the shikimate pathway, 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase (DAHPS), catalyzes an aldol condensation of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), and D-erythrose 4-phosphate (E4P) to produce 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate (DAHP) (Figure 1). According to their protein structure, DAHPSs can be clustered into two distinct homology classes. The microbe derived class I DAHPS contain a bifunctional chorismate mutase (CM)-DAHPS domains, for that reason microbial DAHPSs, for example, E. coli (AroF, G, and H) and S. cerevisiae (Aro3 and 4), are classified as class I DAHPSs. By contrast, class II DAHPS were previously thought to be present only in plant species, but have subsequently been reported in certain microbes such as Streptomyces coelicolor, Streptomyces rimosus, and Neurospora crassa (Bentley, 1990; Maeda and Dudareva, 2012). The DAHPS (AroA) and CM (AroQ) activities of B. subtilis DAHPS are, however, separated by domain truncation. Detailed sequence structure analysis of the bacterial AroA and AroQ families, enzymatic studies with the full-length protein and the truncated domains of AroA and AroQ of B. subtilis, and comparison with fusion proteins of Porphyromonas gingivalis in which the AroQ domain was fused to the C terminus of AroA, suggest that “feedback regulation” may indeed be the evolutionary link between the two classes which are evolved from primitive unregulated member of class II DAHPS (Wu and Woodard, 2006). Class II plant DAHPSs have been reported from carrot roots (Suzich et al., 1985) and potato cell culture (Pinto et al., 1986; Herrmann and Weaver, 1999). DAHPS is encoded by three genes in the Arabidopsis genome (AtDAHPS1, AT4G39980; AtDAHPS2, At4g33510; AtDAHPS3, At1g22410). Orthologous gene search queries using the Arabidopsis DAHPSs, revealed a single gene in algae species (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Volvox carteri, Micromonas sp., and Ostreococcus tauri) and Lotus japonica but two to eight isoforms in other higher plant species (Table 2). AtDAHPS1-type and AtDAHPS2 type genes display differential expression in Arabidopsis thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, and Solanum tuberosum (Maeda and Dudareva, 2012). AtDAHPS1-type genes, which are additionally subject to redox regulation by the ferredoxin-thioredoxin system, exhibit significant induction by wounding and pathogen infection (Keith et al., 1991; Gorlach et al., 1995; Maeda and Dudareva, 2012), whereas AtDAHPS2 type genes display constitutive expression (Gorlach et al., 1995). A phylogenetic analysis of DAHPS genes reveals four major clades, (i) a microphyte clade, (ii) a bryophyte duplication clade, (iii) monocot and dicot woody species clade, (iv) a AtDAHPSs clade (Figure 2Aa). Furthermore, major clade iv has four sub-groups, (iv-a) AtDAHPS2 group, (iv-b) monocot, (iv-c) AtDAHPS1 group and (iv-d) AtDAHP3 group. This result indicates that the constitutively expressed AtDAHPS1 and the stress responsive AtDAHPS 3 type genes display well conserved sequence between species (clade iv-c and iv-d), whereas the second constitutively expressed AtDAHPS2 type genes are clearly separated between monocot and dicot species (clade iv-a).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree analysis of shikimate and phenylalanine biosynthetic genes in 25 species. Amino acid sequence phylogenetic trees of (A) shikimate pathway: (a), DAHPS, (b) DHS, (c) DHQD/SD, (d) SK, (e) ESPS, and (f) CS, (B) phenylalanine related genes, (a) CM and (b) PAT. Amino acid sequences of shikimate biosynthetic genes are obtained from Plaza database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/plaza/). Relationships among the species considered are presented on the Plaza website. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with the aligned protein sequences by MEGA (version 5.10; http://www.megasoftware.net/; Kumar et al., 2004) using the neighbor-joining method with the following parameters: Poisson correction, complete deletion, and bootstrap (1000 replicates, random seed). The protein sequences were aligned by Plaza. Values on the branches indicate bootstrap support in percentages.

3-Dehydroquinate Synthase

The second step of the shikimate pathway is catalyzed by 3-dehydroquinate synthase (DHQS), an enzyme which promotes the intramolecular exchange of the DAHP ring oxygen with carbon 7 to convert DAHP into 3-dehydroquinate. Unlike the fungal situation detailed above, the plant DHQS gene is monofunctional and only found as a single copy in all species with the exception Glycine max which harbors two genes in its genome (Figure 2Ab). Phylogenetic analysis of DHQS genes reveals three major clades consisting of (i) microphyte (ii) bryophyte, (iii) monocot, (iv) Brassicaceae, and (v) dicot species. Intriguingly, by contrast to other shikimate biosynthetic genes, gene expression of DHQS gene is not well correlated to phenylpropanoid production in Arabidopsis (Hamberger et al., 2006).

3-Dehydroquinate Dehydratase/Shikimate Dehydrogenase

3-Deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate is converted to 3-dehydroquinate by the bifunctional enzyme 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase/shikimate dehydrogenase (DHQD/SD), which catalyzes firstly the dehydration of DAHP to 3-dehydroshikimate and consequently the reversible reduction of this intermediate to shikimate using NADPH as co-factor. DHQD/SD exists in three forms; bacterial specific class I shikimate dehydrogenases (AroE type), class II shikimate/quinate dehydrogenases (YdiB type), and class III of shikimate dehydrogenase-like (SHD-l type) (Michel et al., 2003; Singh et al., 2005). In plants class IV, enzymatic activity of DHQD is 10 times higher than SD activity indicating that the amount of 3-dehydroshikimate will be more than sufficient to support flux through the shikimate pathway (Fiedler and Schultz, 1985). This bifunctional enzyme plays an important role in regulating metabolism of several phenolic secondary metabolic pathways (Bentley, 1990; Ding et al., 2007). In general, seed plants contain a single DHQD/SD gene which contains a sequence encoding a plastic transit peptide in their genome (Maeda et al., 2011, Table 2). However, an exception to this statement is Nicotiana tabacum which contains two genes in its genome. Intriguingly, silencing of NtDHD/SHD-1 results strong growth inhibition and reduction of the level of aromatic amino acids, chlorogenic acid, and lignin contents (Ding et al., 2007), however, a second cytosolic isoform can compensate for the production of shikimate but not at the phenotypic level. On a more general basis phylogenetic analysis reveals that microphytes also contain a low number of DHQD/SD genes (between one and two), whilst clear separation between (i) the microphyte clade, (ii) bryophyte clade, (iii) monocot clade, (iv) woody species-specific tandem gene duplication clade, and (v) dicot clades could be observed (Figure 2Ac; Table 2). Interestingly, the observation of the woody species-specific tandem gene duplication clade suggests that these species evolved after DHQD/SD gene duplication. The cytosolic localization of NtDHD/SHD-2 is intriguing since the presence of DAHP synthase, ESPS synthase and CM isoforms lacking N-terminal plastid targeting sequences has been reported (d’Amato, 1984; Mousdale and Coggins, 1985; Ganson et al., 1986). Furthermore, the findings that both ESPS synthase and shikimate kinase (SK) are active even when they retain their target sequences (Dellacioppa et al., 1986; Schmid et al., 1992) suggests that they could also potentially be constituents of a cytosolic pathway. Finally, experiments in which isolated and highly pure mitochondria were supplied with 13C labeled glucose to investigate the binding of the cytosolic isoforms of glycolysis (Giege et al., 2003) also revealed 13C enrichment in shikimate (Sweetlove and Fernie, 2013), indicating that a full cytosolic pathway is likely also in this species.

Shikimate Kinase

The fifth reaction of the shikimate pathway is catalyzed by SK which catalyzes the ATP-dependent phosphorylation of shikimate to shikimate 3-phospate (S3P). E. coli has two SKs, one of class I (AroL type) and one of II (AroK type) which share only 30% sequence identity (Griffin and Gasson, 1995; Whipp and Pittard, 1995; Herrmann and Weaver, 1999). In plants, different numbers of SK isoforms are found in several species; only one in green algae, lycophytes, and bryophytes but between one and three in monocot and dicot plants (Table 2). A phylogenetic analysis of SK genes presents five major clades consisting of (i) microphyte, (ii) bryophyte, (iii) dicot woody species-specific clade, (iv) monocot clade, and (v) dicot species clade (Figure 2Ad). Anaylsis of the SK protein of Spinacia olerancea revealed that it was modulated by energy status and is therefore similar to bacterial SK protein and other ATP-utilizing enzymes (Pacold and Anderson, 1973; Huang et al., 1975; Schmidt et al., 1990). For this reason it has recently been postulated that SK may link to energy requiring shikimate pathway to the cellular energy balance (Maeda and Dudareva, 2012), however, direct experimental support for this hypothesis is currently lacking. In Arabidopsis, homologous genes named SKL1 and SKL2, which are functionally required for chloroplast biogenesis have been demonstrated to have arisen from SK gene duplication (Fucile et al., 2008). SKL1 and SKL2 orthologs have been found in several seed plant species, but not in green algae (Table 2).

5-enolypyruvylshikimate 3-Phosphate Synthase

The 5-enolypyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS, 3-phosphoshikimate 1-carboxyvintltransferase) is the sixth step and here a second PEP is condensed with S3P to form 5-enolpyruvylshiukimate 3-phosphate (EPSP). Since EPSPS is the only known target for the herbicide glyphosate (Steinrucken and Amrhein, 1980), isoforms of this enzyme are often classified according to their sensitivity of glyphosate, glyphosate sensitive EPSPS class I is present in bacteria and plant species, whilst glyphosate insensitive EPSPS class II which has been reported in certain bacteria such as Agrobacterium (Fucile et al., 2011). In plants, different number of EPSPS isoforms is found in several species; only a single isoform in green algae, lycophytes, and bryophytes, but either one or two are found in monocot and dicot species (Table 2). Phylogenetic analysis of EPSPS genes revealed, atypically for genes associated with shikimate metabolism, that five major groups could be observed; (i) microphyte, (ii) bryophyte, (iii) Brassicaceae specific clade, (iv) monocot species, and (v) dicot species clade (Figure 2Ae). There are clear indications that duplicated EPSPS genes in Arabidopsis, apple, grapevine, soybean, and poplar are the result of independent duplication events within their lineages with both copies being maintained in Arabidopsis (Hamberger et al., 2006), however, the reason for the unique divergence in this gene of the pathway is currently unclear.

Chorismate Synthase

Chorismate, the final product of the shikimate pathway, is subsequently formed by chorismate synthase (CS) which catalyzes the trans-1,4 elimination of phosphate from EPSP. CSs are categorized within one of two functional groups (i) fungal type bifunctional CS which are associated with NADPH-dependent flavin reductase or (ii) bacterial and plant type monofunctional CSs (Schaller et al., 1991; Maeda and Dudareva, 2012). The reaction catalyzed by CS requires flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and its overall reaction is redox neutral (Ramjee et al., 1991; Macheroux et al., 1999; Maclean and Ali, 2003). The FMN represents supplies an electron donor for EPSP which facilitates the cleavage of phosphate. The first cloned plant CS gene was that from C. sempervirens (Schaller et al., 1991) which contains a sole CS in its genome. Given that this gene has a 5′ plastid import signal sequence, these results indicate that there may be no CS outside of the plastid this species. Surveying other species revealed that one to two CS genes were present in green algae, lycophytes, and bryophytes as well as dicot specie but that one to three are present in the genomes of apple and leguminous species (Table 2). A phylogenetic analysis of CS genes reveals three major clades constituted by (i) microphyte, (ii) monocot, (iii) dicot species (Figure 2Af).

Chorismate Mutase

Chorismate mutase catalyzes the first step of phenylalanine and tyrosine biosynthesis and additionally represents a key step of toward the branch split of tryptophan biosynthesis. CM catalyzes the transformation of chorismate to prephenate via a Claisen rearrangement. The bacterial minor CM proteins (AroQ type, class I CM) display monofunctional enzymatic activity whilst several bifunctional CMs such as CM-PDT, CM-PDH, and CM-DAHP have been additionally been found in fungi and bacteria (class II CM, Euverink et al., 1995; Romero et al., 1995; Chen et al., 2003; Baez-Viveros et al., 2004). In spite of the fact of only one CM gene is present in algae and lycophyte genomes, more a single gene copy (two to five) are found in bryophytes as well as monocot and dicot species (Table 2). In seed plants, the CM1 bears a putative plastid transit peptide, but CM2 does not and is additionally usually insensitive to allosteric regulation by aromatic amino acids (Benesova and Bode, 1992; Eberhard et al., 1996; Maeda and Dudareva, 2012). Several plant species, especially dicot plants, have an additional CM3 family gene which displays high sequence similarity to CM2 yet bears a putative plastid transit peptide. For example, Arabidopsis has three isozymes named AtCM1 (At3g29200), AtCM2 (At5g10870), and AtCM3 (At1g69370) (Mobley et al., 1999; Tzin and Galili, 2010). Phylogenetic analysis of the CS genes reveals three major clades constituting of (i) AtCM2 clade, (ii) microphyte and bryophyte clade, and (iii) AtCM2 clade (Figure 2Ba). Additionally, clade iii shows two sub-groups, (iii-a) AtCM3 sub-groups and (iii-b) AtCM1 sub-group (Figure 2Ba) (Eberhard et al., 1996). In spite of that the CM2 sub-group contains all species of seed plants, monocot species are not contained into AtCM3 sub-group. Recently the importance of CM has been extended beyond intracellular metabolism, In Zea mays, the chorismate mutase Cmu1 secreted by Ustilago maydis, a widespread pathogen characterized by the development of large plant tumors and commonly known as smut, is a virulence factor. The uptake of the Ustilago CMu1 protein by plant cells allows rerouting of plant metabolism and changes the metabolic status of these cells via metabolic priming (Djamei et al., 2011). It now appears that secreted CMs are found in many plant-related microbes and this form of host manipulation would appear to be a general weapon in the arsenal of plant pathogens.

Prephenate Aminotransferase and Arogenate Dehydratase

Prephenate aminotransferase (PAT) and arogenate dehydratase (ADT) catalyze the final steps for production of phenylalanine. Whilst ADT was first cloned in 2007 (Cho et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2010), it is only more recently that PAT was cloned. Papers published in 2011 identified PAT in Petunia hybrid, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Solanum lycopersicum (Dal Cin et al., 2011; Maeda et al., 2011) and established that it directs carbon flux from prephenate to arogenate but also that it is strongly and co-ordinately upregulated with genes of primary metabolism and phenylalanine derived flavor volatiles. In plant species, a different number of PAT isoforms have been found. Although green algae only contain single PAT and ADT genes, monocot species have between one and two PATs and between two and four ADTs whilst dicot plants genomes contain the same number of PATs but two to eight ADTs (Table 2). Phylogenetic analysis of PAT genes shows three major clades of (i) microphyte, (ii) monocot, and (iii) dicot species (Figure 2Bb).

Genes Involved in Plant Phenolic Secondary Metabolisms

Phenolic secondary metabolism displays an immense chemical diversity due to the evolution of enzymatic genes which are involved in the various biosynthetic and decorative pathways. Such variation is caused by diversity and redundancy of several key genes of phenolic secondary metabolism such as PKSs, cytochrome P450s (CYPs), Fe2+/2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases (2ODDs), and UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs). On the other hand, there are other general phenylpropanoid related biosynthetic genes, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H), and 4-coumarate:coenzyme A ligase (4CL), which are required in order to differentiate various classes of phenolic secondary metabolism. All of these core genes encode important enzymes which activate a number of hydroxycinnamic acids to provide precursors for the biosynthesis of lignins, monolignals, and indeed all other major phenolic secondary metabolites in higher plants (Lozoya et al., 1988; Allina et al., 1998; Hu et al., 1998; Ehlting et al., 1999; Lindermayr et al., 2002; Hamberger and Hahlbrock, 2004). Since phenolic secondary metabolism display considerable species-specificity, investigation of the genes encoding the responsible biosynthetic enzymes are frequently used as an example of chemotaxonomy for understanding plant evolution. However, considering the evolution of these genes in isolation is rather restrictive a deeper understanding is provided by combining this with investigation of the evolution of the shikimate-phenylalanine biosynthetic genes in the green lineage.

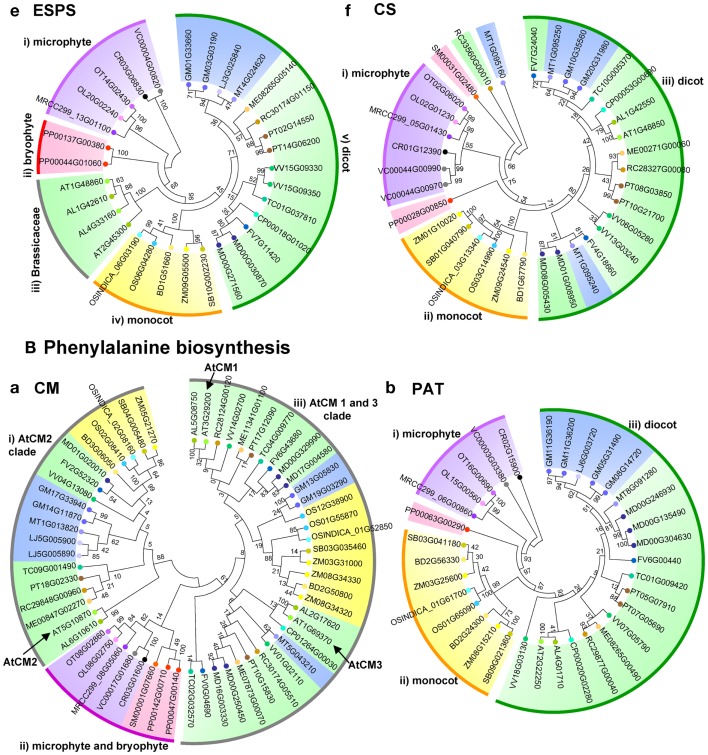

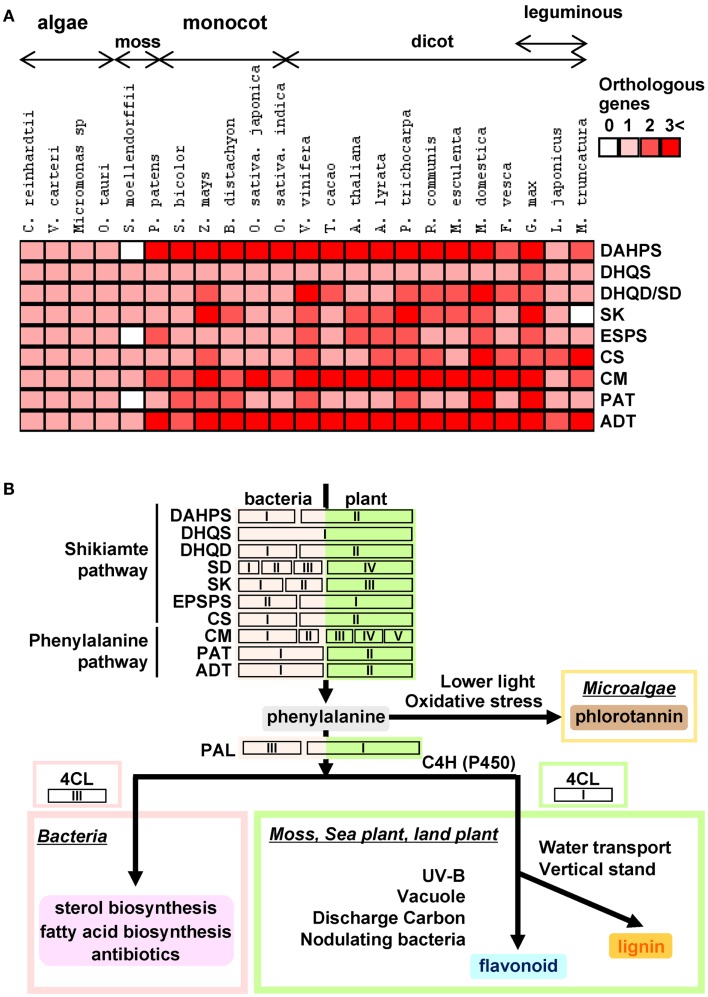

Conclusion

During the long evolutionary period covered from aquatic algae to land plants, plants have adapted to the environmental niches with the evolutionary strategies such as gene duplication and convergent evolution by the filtration of natural selection. Genes of plant shikimate biosynthesis have evolved accordingly (Figure 3). In this review, we demonstrated that biosynthetic genes of aromatic amino acid primary metabolism are well conserved between algae and all land plants. However, in contrast to algae species which have neither isoforms nor duplicated genes in their genomes, all land plants harbor gene duplications including tandem gene duplications which are particularly prominent in the cases of DAHPS, DHQD/SD, CS, CM, and ADT (Figure 3A; Table 2). Our phylogenetic analysis revealed clear separation between algae, monocots, dicots, woody species, and leguminous plants. Analysis of the presence and copy number of key genes across these species gives several hints as to how to improve our understanding of the scaffold from which these genes have evolved. However, the exact evolutionary pressures on genes of shikimate biosynthesis including the unique occurrence of the Arom complex will require considerable further studies. That said it is intriguing to compare and contrast biosynthetic genes of those downstream of them in the production of plant phenolics (Figure 3B). Interestingly, shikimate pathway genes are ubiquitous across the green lineage whilst this cannot be said for all downstream genes of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Furthermore, there is a much greater gene duplication within phenylpropanoid than shikimate biosynthesis (Figure 3A; Table 2). This fact also reflected in the level of chemical diversity of the respective pathways with the essentiality of the shikimate pathway preventing much diversity, but phenylpropanoid species often being redundant in function to one another. It would seem likely that the phenylpropanoid pathway initially arose via mutations accumulating in the shikimate pathway genes. However, whilst these were potentially beneficial in land plants for reasons we discuss in our recent review of these compounds (Tohge et al., 2013) they do not appear to share the essentiality of shikimate across the entire green lineage.

Figure 3.

Heat map for isoforms of shikimate-phenylalanine biosynthetic genes in plant genomes and hypothetical scheme for the evolution of phenylalanine derived phenolic secondary metabolism. (A) Heap map overview of number of shikimate-phenylalanine biosynthetic gene isoforms in 25 species. (B) Hypothetical schematic figure for shikimate-phenylalanine biosynthetic genes and their evolution of phenolic secondary metabolism.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Research activity of Takayuki Tohge is supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Funding from the Max-Planck-Society (to Takayuki Tohge, Mutsumi Watanabe, Rainer Hoefgen, Alisdair R. Fernie) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Allina S. M., Pri-Hadash A., Theilmann D. A., Ellis B. E., Douglas C. J. (1998). 4-Coumarate: coenzyme A ligase in hybrid poplar – properties of native enzymes, cDNA cloning, and analysis of recombinant enzymes. Plant Physiol. 116, 743–754 10.1104/pp.116.2.743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baez-Viveros J. L., Osuna J., Hernandez-Chavez G., Soberon X., Bolivar F., Gosset G. (2004). Metabolic engineering and protein directed evolution increase the yield of l-phenylalanine synthesized from glucose in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 87, 516–524 10.1002/bit.20159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benesova M., Bode R. (1992). Chorismate mutase isoforms from seeds and seedlings of Papaver somniferum. Phytochemistry 31, 2983–2987 10.1016/0031-9422(92)83431-W [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley R. (1990). The shikimate pathway – a metabolic tree with many branches. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 25, 307–384 10.3109/10409239009090615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. Q., Vincent S., Wilson D. B., Ganem B. (2003). Mapping of chorismate mutase and prephenate dehydrogenase domains in the Escherichia coli T-protein. Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 757–763 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03451.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho M.-H., Corea O. R. A., Yang H., Bedgar D. L., Laskar D. D., Anterola A. M., et al. (2007). Phenylalanine biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana – identification and characterization of arogenate dehydratases. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 30827–30835 10.1074/jbc.M702950200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corea O. R. A., Ki C., Cardenas C. L., Kim S.-J., Brewer S. E., Patten A. M., et al. (2012). Arogenate dehydratase isoenzymes profoundly and differentially modulate carbon flux into lignins. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 11446–11459 10.1074/jbc.M111.322164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin V., Tieman D. M., Tohge T., McQuinn R., de Vos R. C. H., Osorio S., et al. (2011). Identification of genes in the phenylalanine metabolic pathway by ectopic expression of a MYB transcription factor in tomato fruit. Plant Cell 23, 2738–2753 10.1105/tpc.111.086975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Amato T. A., Ganson R. J., Gaines C. G., Jensen R. A. (1984). Subcellular localization of chorismate-mutase isoenzymes in protoplasts from mesophyll suspension-cultured cells of Nicotiana silvestris. Planta 162, 104–108 10.1007/BF00410205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellacioppa G., Bauer S. C., Klein B. K., Shah D. M., Fraley R. T., Kishore G. M. (1986). Translocation of the precursor of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase into chloroplasts of higher-plants in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 6873–6877 10.1073/pnas.83.18.6873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L., Hofius D., Hajirezaei M.-R., Fernie A. R., Boernke F., Sonnewald U. (2007). Functional analysis of the essential bifunctional tobacco enzyme 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase/shikimate dehydrogenase in transgenic tobacco plants. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 2053–2067 10.1093/jxb/erm227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djamei A., Schipper K., Rabe F., Ghosh A., Vincon V., Kahnt J., et al. (2011). Metabolic priming by a secreted fungal effector. Nature 478, 395. 10.1038/nature10454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosselaere F., Vanderleyden J. (2001). A metabolic node in action: chorismate-utilizing enzymes in microorganisms. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 27, 75–131 10.1080/20014091096710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke S. O., Powles S. B. (2008). Glyphosate: a once-in-a-century herbicide. Pest Manag. Sci. 64, 319–325 10.1002/ps.1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan K., Edwards R. M., Coggins J. R. (1987). The pentafunctional arom enzyme of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a mosaic of monofunctional domains. Biochem. J. 246, 375–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard J., Ehrler T. T., Epple P., Felix G., Raesecke H. R., Amrhein N., et al. (1996). Cytosolic and plastidic chorismate mutase isozymes from Arabidopsis thaliana: molecular characterization and enzymatic properties. Plant J. 10, 815–821 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.10050815.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlting J., Buttner D., Wang Q., Douglas C. J., Somssich I. E., Kombrink E. (1999). Three 4-coumarate: coenzyme A ligases in Arabidopsis thaliana represent two evolutionarily divergent classes in angiosperms. Plant J. 19, 9–20 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00491.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euverink G. J. W., Hessels G. I., Franke C., Dijkhuizen L. (1995). Chorismate mutase and 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase of the methylotrophic actinomycete Amycolatopsis methanolica. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 3796–3803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler E., Schultz G. (1985). Localization, purification, and characterization of shikimate oxidoreductase-dehydroquinate hydrolase from stroma of spinach-chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 79, 212–218 10.1104/pp.79.1.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucile G., Falconer S., Christendat D. (2008). Evolutionary diversification of plant shikimate kinase gene duplicates. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000292. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucile G., Garcia C., Carlsson J., Sunnerhagen M., Christendat D. (2011). Structural and biochemical investigation of two Arabidopsis shikimate kinases: the heat-inducible isoform is thermostable. Protein Sci. 20, 1125–1136 10.1002/pro.640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganson R. J., D’Amato T. A., Jensen R. A. (1986). The two-isozyme system of 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase in Nicotiana silvestris and other higher plants. Plant Physiol. 82, 203–210 10.1104/pp.82.1.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giege P., Heazlewood J. L., Roessner-Tunali U., Millar A. H., Fernie A. R., Leaver C. J., et al. (2003). Enzymes of glycolysis are functionally associated with the mitochondrion in Arabidopsis cells. Plant Cell 15, 2140–2151 10.1105/tpc.012500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlach J., Raesecke H. R., Rentsch D., Regenass M., Roy P., Zala M., et al. (1995). Temporally distinct accumulation of transcripts encoding enzymes of the prechorismate pathway in elicitor-treated, cultured tomato cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 3166–3170 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin H. C., Gasson M. J. (1995). The gene (aroK) encoding shikimate kinase-I from Escherichia coli. DNA Seq. 5, 195–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger B., Ehlting J., Barbazuk B., Douglas C. J. (2006). Comparative genomics of the shikimate pathway in Arabidopsis, Populus trichocarpa and Oryza sativa: shikimate pathway gene family structure and identification of candidates for missing links in phenylalanine biosynthesis. Recent Adv. Phytochem. 40, 85–113 10.1016/S0079-9920(06)80038-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger B., Hahlbrock K. (2004). The 4-coumarate: CoA ligase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana comprises one rare, sinapate-activating and three commonly occurring isoenzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 2209–2214 10.1073/pnas.0307307101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann K. M., Weaver L. M. (1999). The shikimate pathway. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 473–503 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W. J., Kawaoka A., Tsai C. J., Lung J. H., Osakabe K., Ebinuma H., et al. (1998). Compartmentalized expression of two structurally and functionally distinct 4-coumarate: CoA ligase genes in aspen (Populus tremuloides). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 5407–5412 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Montoya A. L., Nester E. W. (1975). Purification and characterization of shikimate kinase enzyme-activity in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 250, 7675–7681 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T., Tohge T., Lytovchenko A., Fernie A. R., Jander G. (2010). Pleiotropic physiological consequences of feedback-insensitive phenylalanine biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 63, 823–835 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith B., Dong X. N., Ausubel F. M., Fink G. R. (1991). Differential induction of 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase genes in Arabidopsis thaliana by wounding and pathogenic attack. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 8821–8825 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Tamura K., Nei M. (2004). MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5, 150–163 10.1093/bib/5.2.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindermayr C., Mollers B., Fliegmann J., Uhlmann A., Lottspeich F., Meimberg H., et al. (2002). Divergent members of a soybean (Glycine max L.) 4-coumarate: coenzyme A ligase gene family – primary structures, catalytic properties, and differential expression. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 1304–1315 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02775.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozoya E., Hoffmann H., Douglas C., Schulz W., Scheel D., Hahlbrock K. (1988). Primary structures and catalytic properties of isoenzymes encoded by the 2 4-coumarate-coa ligase genes in parsley. Eur. J. Biochem. 176, 661–667 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden J., Coggins J. R. (1977). Subunit structure of arom multienzyme complex of neurospora-crassa – possible pentafunctional polypeptide-chain. Biochem. J. 161, 599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macheroux P., Schmid J., Amrhein N., Schaller A. (1999). A unique reaction in a common pathway: mechanism and function of chorismate synthase in the shikimate pathway. Planta 207, 325–334 10.1007/s004250050489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean J., Ali S. (2003). The structure of chorismate synthase reveals a novel flavin binding to a unique chemical reaction. Structure 11, 1499–1511 10.1016/j.str.2003.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H., Dudareva N. (2012). The shikimate pathway and aromatic Amino acid biosynthesis in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 73–105 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H., Yoo H., Dudareva N. (2011). Prephenate aminotransferase directs plant phenylalanine biosynthesis via arogenate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 19–21 10.1038/nchembio.485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel G., Roszak A. W., Sauve V., Maclean J., Matte A., Coggins J. R., et al. (2003). Structures of shikimate dehydrogenase AroE and its paralog YdiB – a common structural framework for different activities. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 19463–19472 10.1074/jbc.M210358200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobley E. M., Kunkel B. N., Keith B. (1999). Identification, characterization and comparative analysis of a novel chorismate mutase gene in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene 240, 115–123 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00423-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousdale D. M., Coggins J. R. (1985). Subcellular localization of the common shikimate-pathway enzymes in Pisum sativum L. Planta 163, 241–249 10.1007/BF00393514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W. T., Fahrendorf T., Ballance G. M., Lamb C. J., Dixon R. A. (1996). Stress responses in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) 0.20. Transcriptional activation of phenylpropanoid pathway genes in elicitor-induced cell suspension cultures. Plant Mol. Biol. 30, 427–438 10.1007/BF00049322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacold I., Anderson L. E. (1973). Energy charge control of Calvin cycle enzyme 3-phosphoglyceric acid kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 51, 139–143 10.1016/0006-291X(73)90519-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto J., Suzich J. A. A., Herrmann K. M. (1986). 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase from potato-tuber (Solanum-Tuberosum-L.). Plant Physiol. 82, 1040–1044 10.1104/pp.82.4.1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramjee M. N., Coggins J. R., Hawkes T. R., Lowe D. J., Thorneley R. N. F. (1991). Spectrophotometric detection of a modified flavin mononucleotide (Fmn) intermediate formed during the catalytic cycle of chorismate synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 8566–8567 10.1021/ja00022a078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R. M., Roberts M. F., Phillipson J. D. (1995). Chorismate mutase in microorganisms and plants. Phytochemistry 40, 1015–1025 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00408-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller A., Vanafferden M., Windhofer V., Bulow S., Abel G., Schmid J., et al. (1991). Purification and characterization of chorismate synthase from Euglena gracilis – comparison with chorismate synthases of plant and microbial origin. Plant Physiol. 97, 1271–1279 10.1104/pp.97.4.1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid J., Schaller A., Leibinger U., Boll W., Amrhein N. (1992). The in vitro synthesized tomato shikimate kinase precursor is enzymatically active and is imported and processed to the mature enzyme by chloroplasts. Plant J. 2, 375–383 10.1111/j.1365-313X.1992.00375.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt C. L., Danneel H. J., Schultz G., Buchanan B. B. (1990). Shikimate kinase from spinach-chloroplasts – purification, characterization, and regulatory function in aromatic amino-Acid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 93, 758–766 10.1104/pp.93.2.758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Korolev S., Koroleva O., Zarembinski T., Collart F., Joachimiak A., et al. (2005). Crystal structure of a novel shikimate dehydrogenase from Haemophilus influenzae. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17101–17108 10.1074/jbc.M504877200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinrucken H. C., Amrhein N. (1980). The herbicide glyphosate is a potent inhibitor of 5-enolpyruvyl-shikimic-acid 3-phosphate synthase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 94, 1207–1212 10.1016/0006-291X(80)90547-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzich J. A., Dean J. F. D., Herrmann K. M. (1985). 3-Deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase from carrot root (Daucus carota) is a hysteretic enzyme. Plant Physiol. 79, 765–770 10.1104/pp.79.3.765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetlove L. J., Fernie A. R. (2013). Spatial organization of metabolism within the plant cell. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohge T., Watanabe M., Hoefgen R., Fernie A. R. (2013). The evolution of phenylpropanoid metabolism in the green lineage. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.3109/10409238.2012.758083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzin V., Galili G. (2010). New insights into the shikimate and aromatic amino acids biosynthesis pathways in plants. Mol. Plant 3, 956–972 10.1093/mp/ssq048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss U. (1986). “Early research on the shikimate pathway: some personal remarks and reminiscences,” in The Shikimic Acid Pathway, Vol. 20, ed. Conn E. E. (Davis: University of California; ), 1–12 [Google Scholar]

- Whipp M. J., Pittard A. J. (1995). A reassessment of the relationship between aroK-encoded and aroL-encoded shikimate kinase enzymes of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177, 1627–1629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Woodard R. W. (2006). New insights into the evolutionary links relating to the 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase subfamilies. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4042–4048 10.1074/jbc.M605756200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]