Abstract

Background

A long-term prospective assessment of QoL in cervical cancer patients is still lacking. Here, we provide the first 2-years prospective, longitudinal study evaluating emotional distress and QoL in early stage (ECC) and locally advanced (LACC) cervical cancer patients who remained disease-free 2-years from diagnosis.

Methods

The questionnaires: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Global Health Status items of EORTC QLQ-C30 (GHS), and EORTC QLQ-CX24 (CX24) have been administered by a dedicated team of psycho-oncologists, administered at baseline, and after 3, 6, 12 and 24 months from surgery The Generalized Linear Model for repeated measure was used to analyze modifications of QoL measures over time.

Results

In both groups, an early reduction of the percentage of patients with anxiety levels ≥11 was observed at the 3-month evaluation (ECC: 25.7% at baseline Vs 14.7% after 3 months, p value=0.001; LACC: 22.2% at baseline Vs 15.4% after 3 months, p value=0.001). Despite this favorable trend, after 2 years from diagnosis, 11.9% of ECC and 15.6% of LACC patients still showed an anxiety score ≥11. No significant changes over time were observed in term of Depression levels. Focusing on QoL issues, mean GHS and Sexual Activity scores showed an improvement over time in both groups compared to baseline (GHS: 5.7% difference for ECC, p value=0.001, and 11.0% in LACC, p value=0.001; SXA: 13.9% difference for ECC, p value=0.001; and 6.1% in LACC, p value=0.008). On the other hand, Body Image mean scores were significantly impaired by chemoradiation administration in LACC patients, without long-term recovery (7.5% difference, p value=0.001). Finally, in both groups, lymphedema (LY) and menopausal symptoms (MS) showed an early worsening which persisted 2-year after surgery (LY: 19.5% difference for ECC, p value=0.014, and 27.3% in LACC, p value=0.001; MS: 14.4% difference for ECC, p value=0.004, and 16.0% in LACC, p value=0.002).

Conclusions

Despite a significant improvement over time, elevated anxiety levels are still detectable at 24 months after surgery in approximately 10% of cervical cancer patients. Much more attention should be focused on surgical/medical approaches able to minimize the negative impact of lymphedema and menopausal symptoms on QoL.

Keywords: Quality of life, Emotional distress, Cervical cancer, Prospective study, Long-term evaluation

Background

Over the last decade, increasing attention has been focused on the issues of emotional distress and quality of life (QoL) in women with gynecological cancer [1,2]. This renewed attention comes from the growing awareness that cancer diagnosis and the consequences of multimodal treatments deeply affect woman’s self-identity, impairing her social/intimate relationships, as well as her overall self-perception as mother and wife [3-5]. These considerations are supported by prevalence studies, which estimated that a new diagnosis of gynecological cancer is associated with moderate/severe anxiety or depression in about 50% of women [6,7].

In particular, among gynecological cancer patients, those affected by cervical cancer have been reported to show the worst scores in terms of emotional distress and QoL [4,5,8], given their younger age, and the need to undergo integrated therapies and aggressive surgical procedures [9,10]. Moreover, several experiences suggest that anxiety, depression and QoL deterioration persist for months to years since diagnosis, but the variables influencing the time interval to spontaneous recovery are far from being clarified [11-15].

The available literature on this specific field shows a large variability, and it can be justified by the retrospective nature of the studies, which are often cross-sectional, performed at different time intervals from treatment and lacking of baseline evaluations. For these reasons, we have performed a prospective and longitudinal collection of data on QoL levels in early (ECC) and locally advanced (LACC) cervical cancer patients treated with radical surgery (RS) or chemoradiation (CT/RT) followed by RS, respectively [16].

Here, we provide an updated analysis of previously published data, describing the longitudinal modifications of anxiety/depression and QoL scores, in a large cohort of cervical cancer patients who remained disease-free 2 years from diagnosis. We identify in this study also the clinico-pathological and socio-demographic features influencing emotional distress and QoL levels.

Methods

Study design and recruitment

We conducted in our Institution, a prospective, longitudinal study, collecting specific measures of emotional distress and QoL in a large cohort of cervical cancer patients. Eligibility criteria include: histological diagnosis of cervical carcinoma, age≥18 years, ability to read and understand Italian language, and absence of any evident cognitive impairment. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and by the Ethical Committee of the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart. All ECC patients (FIGO Stage IB-IIA <4 cm tumor size) were treated with radical hysterectomy plus pelvic lymphadenectomy, while LACC patients (FIGO stage IB-IIA >4 cm tumor size, IIB-IVA) received concomitant chemoradiation (CT/RT) followed by RS in case of response, as previously reported [17-19].

Measures

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were evaluated with the Italian validated version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS including 14 items) questionnaire [20,21]. Responses were provided on verbal scales coded 0–3, and were grouped as follows: 0–7=normal, 8–10=borderline, 11–21=abnormal, according to the original version of HADS validated by Zigmond et al. [21].

Patients QoL was assessed administering the Global Health Status scale of EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) (GHS including 2 items) and the EORTC QLQ-CX24 (CX24 including 22 items) questionnaires [22,23]. Scores were obtained after a linear transformation of data according to the procedures validated by the EORTC QoL Group [22,23]. Higher scores on the GHS and Sexual activity subscales indicate a higher level of functioning and a better QoL, whereas, for the remaining subscales (i.e. HADS, Symptom experience, Body image, Lymphedema, Menopausal symptoms), higher levels correspond to worse or more symptoms.

EORTC published guidelines were applied for the interpretation of clinical relevant changes of GHS scores [24]. Furthermore, as previously reported, a difference larger than 5% of mean score values compared to baseline was considered as indicating a difference of clinical interest for the EORTC QLQ-CX24 and HADS subscales [25,26].

Study procedures

Written informed consent to the study procedures was obtained from all eligible patients. Baseline questionnaires were administered within a week from communication of diagnosis and before any counseling about treatment. Patients had also to complete the questionnaires 3, 6, 12 and 24 months after surgery. For LACC patients an additional time point for QoL assessment was planned after 4–5 weeks from completion of chemoradiation. QoL evaluations were discontinued in patients experiencing recurrence/progression of disease. All questionnaires were administered by psycho-oncologists from our hospital service.

Statistical analysis

Only patients who completed all questionnaires, at all time points, were considered eligible and included in the final analysis. All analyses were performed separately in ECC and LACC groups in order to reduce sample heterogeneity. ANOVA was used to analyze the baseline differences of QoL scores according to group of disease. Categorical variable were examined using the Fisher’s exact test. The Generalized Linear Model (GLM) for repeated measure ANOVA test was used to analyze modifications of QoL measures over time: a p value< 0.05 was taken as statistically significant. The Between Subject test was used to investigate the association between factors and the changes over time in term of patients’ anxiety scores. The SPSS Software 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to carry on statistical analysis.

Results

Compliance

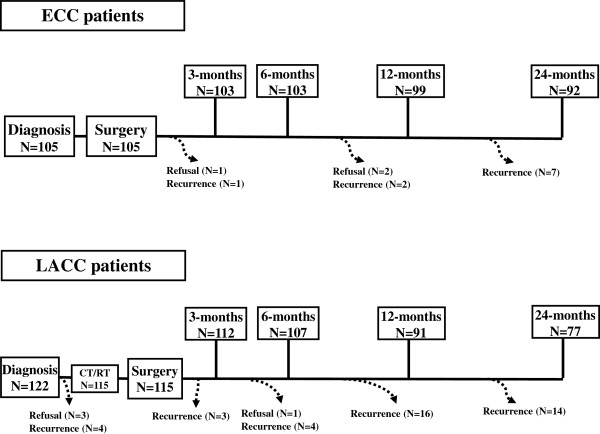

Between February 2007 and July 2010, 227 patients were enrolled in the study (Figure 1). During the study timeframe, we observed 10 (9.5%), and 41 (33.6%) recurrences, in ECC and LACC patients, respectively; 3 (2.8%) ECC and 4 LACC (3.3%) women refused to complete all study evaluations. Therefore, 92 ECC and 77 LACC patients were considered eligible for final analysis (overall study compliance=96.1%).

Figure 1.

Time line of questionnaire administration, and flow chart of our patient population.

Characteristics and socio-demographics features

As shown in Table 1, at diagnosis, LACC patients resulted older and more frequently postmenopausal than ECC patients. We did not observe differences, in terms of co-morbidities and adjuvant therapies, between the two groups. The vast majority of patients was married (63.8%), lived with someone (87.6%), had children (80.2%), and a higher education level (84.1%); on the other hand, 51.7% of women were unemployed/retired. No statistically significant differences were detected in the distribution of clinico-pathological and socio demographics features between eligible patients and women excluded from the final analysis due to refusal or recurrence/progressive disease.

Table 1.

Characteristics and socio-demographic features according to stage of disease

| Characteristics | Total No. (%) | Early stage cervical cancer No. (%) | Locally advanced cervical cancer No. (%) | pvaluea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Whole series |

227 |

105 (46.3) |

122 (53.7) |

- |

|

Age, years |

|

|

|

|

| Median (range) |

50.0 (27.3-82.0) |

46.1 (27.3-82.0) |

52.5 (29.1-81.2) |

0.001b |

|

Menopause (at diagnosis) |

|

|

|

|

| No |

124 (54.6) |

68 (64.8) |

56 (45.9) |

|

| Yes |

103 (45.4) |

37 (35.2) |

66 (54.1) |

0.006 |

|

Co-morbid conditions |

|

|

|

|

| No |

173 (76.2) |

84 (80.0) |

89 (72.9) |

|

| Yes |

54 (23.8) |

22 (20.0) |

32 (27.1) |

0.234 |

|

Adjuvant Therapy |

|

|

|

|

| None |

162 (71.3) |

77 (73.3) |

85 (69.6) |

|

| Yes |

65 (28.7) |

28 (26.7) |

37 (30.4) |

0.312 |

|

Use of antidepressant drugs |

|

|

|

|

| No |

193 (85.1) |

90 (85.7) |

103 (84.4) |

|

| Yes |

34 (14.9) |

15 (14.3) |

19 (15.6) |

0.853 |

|

Marital Status |

|

|

|

|

| Married |

145 (63.8) |

70 (66.7) |

75 (61.4) |

|

| Not married/widowed/divorced |

82 (36.2) |

35 (33.3) |

47 (38.6) |

0.483 |

|

Living status |

|

|

|

|

| Alone |

28 (12.3) |

10 (9.5) |

18 (14.7) |

|

| Not alone |

199 (87.7) |

95 (90.5) |

104 (85.3) |

0.312 |

|

Children |

|

|

|

|

| No |

45 (19.8) |

19 (18.1) |

26 (21.3) |

|

| Yes |

182 (80.2) |

86 (81.9) |

96 (78.7) |

0.614 |

|

Education level |

|

|

|

|

| Primary school |

36 (15.8) |

12 (11.4) |

24 (19.7) |

|

| High school/graduation) |

191 (84.2) |

93 (88.6) |

98 (80.3) |

0.102 |

|

Employment status |

|

|

|

|

| Employed |

111 (48.9) |

49 (46.7) |

62 (50.8) |

|

| Unemployed/retired | 116 (51.1) | 56 (53.3) | 60 (49.2) | 0.623 |

a calculated by Fisher’s exact test for proportion.

b calculated by Wilcoxon rank sum non parametric test.

Anxiety and depression

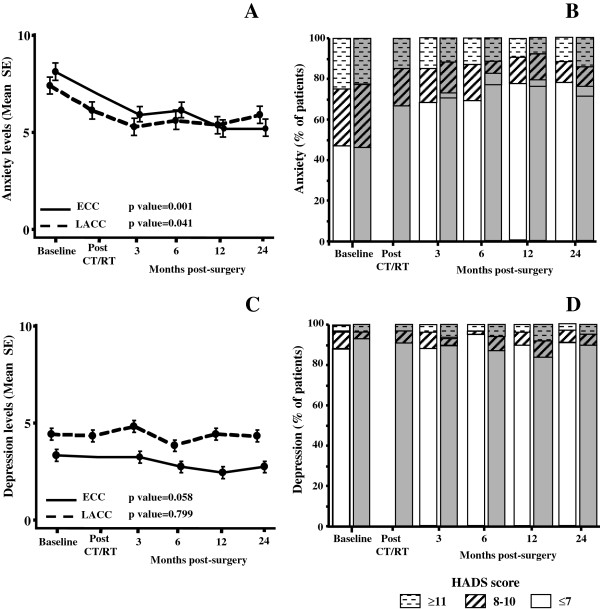

Longitudinal changes of anxiety and depression scores are reported in Figure 2. At baseline, mean anxiety levels did not significantly differ between ECC and LACC patients (p value=0.443). Both groups experienced a statistically significant early (3 months after surgery) improvement of anxiety scores, which persisted until the 24-month evaluation (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Plots of HADS-anxiety (A) and depression (C) mean scores at each assessment (Error bars indicate standard deviations). Longitudinal changes over time in the distribution of patients with normal (HADS scores≤7), borderline (HADS scores 8–10), and severe (HADS scores ≥11) levels of anxiety (B) and depression (D) according to the extent of disease; ECC patients: white column, LACC patients: gray columns.

As shown in Figure 2B, at baseline, an anxiety score ≥11 was documented in 25.7% and 22.2% of ECC and LACC patients, respectively. A statistically significant reduction of the percentage of patients with severe anxiety levels was observed at the 3-month evaluation in both groups (ECC=14.7%, p value=0.001; LACC=15.4%, p value=0.001); but, after 2 years from diagnosis, 11.9% and 15.6% of ECC and LACC patients still showed an anxiety score ≥11.

As far as depression is concerned, low and comparable mean scores were detected at baseline in both ECC and LACC patients (p value=0.669), with only 3% of patients showing HADS-depression levels ≥11. We did not find any change of mean depression scores or distribution of cases with pathological depression scores over time (Figure 2C, D).

Univariate analysis showed that ECC patients, who were not in menopause at diagnosis, had worse anxiety scores, although this association went lost in multivariate analysis. On the other hand, in LACC patients, multivariate analysis showed that only living status not alone was significantly associated with higher anxiety scores (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the association between socio-demographic features and changes over time of anxiety scores in ECC and LACC patients

|

Independent variable |

ECC |

LACC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association with higher anxiety scores | Univariate (p value) | Multivariatea (p value) | Association with higher anxiety scores | Univariate (p value) | Multivariate (p value) | |

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ≤45 years |

No difference |

0.971 |

/ |

No difference |

0.371 |

/ |

| >45 years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Menopausal status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

Yes (direct) |

0.056 |

0.242 |

No difference |

0.254 |

/ |

| Yes |

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Co-morbidities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

No difference |

0.701 |

/ |

No difference |

0.820 |

/ |

| Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Married |

No difference |

0.105 |

0.270 |

No difference |

0.300 |

/ |

| Not married |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Living status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Alone |

No difference |

0.114 |

0.733 |

No |

0.023 |

0.002 |

| Not alone |

|

|

|

Yes (direct) |

|

|

|

Children |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

No difference |

0.332 |

/ |

No difference |

0.215 |

0.635 |

| Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Educational level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Primary school |

No difference |

0.114 |

0.225 |

Yes (direct) |

0.040 |

0.773 |

| High/graduation |

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

Employment status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Employed |

No difference |

0.763 |

/ |

No difference |

0.623 |

/ |

| Unemployed/retired | ||||||

a p values calculated by the Between Subject test including in multivariate analysis all variables showing a p value≤0.20 in univariate analysis (Generalized linear model).

As far as depression scores is concerned, there was no association between patients’ characteristics and depression levels, both in univariate and multivariate analysis (data not shown).

QoL subscales

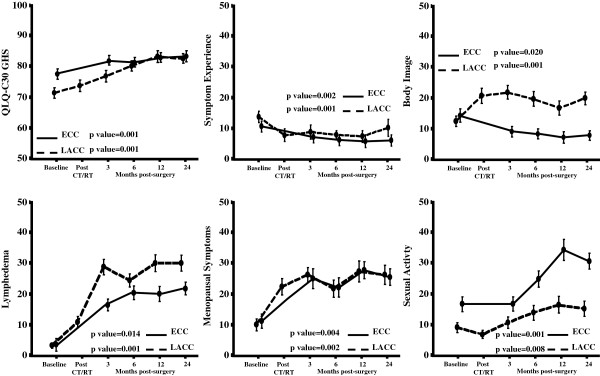

As shown in Figure 3, in ECC patients, GHS scores showed a slight clinically significant improvement over time (5.7% difference in mean score compared to baseline); similarly a clinically and statistically significant improvement of GHS scores (11.0% difference in mean score compared to baseline) was documented in LACC patients at the 24-month compared to baseline evaluation (p value=0.001).

Figure 3.

Plots of the QoL scales/items showing statistically significant variations over time (Error bars indicate standard deviations).

Regarding symptom experience (SE), the difference of mean scores was never clinically significant (less than 5%).

On the other hand, differently from ECC patients, who experienced a little but progressive improvement of body image (BI) scores over time, LACC patients showed a relevant deterioration of BI levels, which arose shortly after CT/RT administration and did not show a return to basal levels even after 2 years since diagnosis.

As far as lymphedema (LY) is concerned, we observed a dramatic and persistent worsening of mean scores over time both in ECC (difference of 19.5 in mean values compared to baseline at 24 months from surgery, p value=0.014), and LACC cases (difference of 27.3 in mean values compared to baseline at 24 months from surgery, p value=0.001).

Similarly, we observed in both groups a significant deterioration of scores of menopausal symptoms (MS), without a recovery after 24 months from surgery.

Finally, scores relative to sexual activity showed a marked improvement over time with a difference of mean score values compared to baseline of 13.9% for ECC (p value=0.001), and 6.1% for LACC patients (p value=0.008).

In ECC patients, the only association retained in multivariate analysis was between premenopausal status at diagnosis and worse menopausal symptoms (p value=0.001). In LACC patients, the only statistically significant association, confirmed in multivariate analysis, was detected between having children and poor GHS score values (p value=0.053) (data not shown).

Discussion

We reported for the first time a long-term, prospective, longitudinal evaluation of emotional distress and QoL in a large series of women with ECC and LACC. During the whole study period, around one thousand of questionnaires have been successfully administered with a relevant patients’ compliance to the study (96.1%). This low “refusal rate” could reflect the appreciation of patients for the efforts made to bring out their unmet needs; furthermore, administration of questionnaires could have been seen by the patients as a precious opportunity for processing their own disease experiences.

Looking at emotional issues, we reported baseline severe HADS-anxiety scores in approximately 20-25% of patients, confirming previously published data [6,7,27-29]. Moreover, there were no differences in baseline anxiety scores between ECC and LACC patients; thus suggesting that, since baseline evaluation was administered before any counseling about treatment, the development of severe anxiety could be mainly related to the communication of cancer diagnosis, rather than to concerns regarding the extent of disease and the treatment modalities.

We documented a significant improvement of anxiety levels in both groups at the 3-month evaluation, confirming that the first 100 days after diagnosis play a crucial role in the process of emotional recovery [11,26]. Therefore, it is not surprising that interventions on psychological symptoms have been primarily investigated in the early phase after cancer diagnosis [28,30]. However, it has to considered that in our study, anxiety levels reached a plateau over 2 years, and severe anxiety scores were still detectable in 10-15% of patients. Similar results were reported by Wenzel et al., who documented persistent psychological sequelae in a large series of long-term survivors, with around 50% of respondents expressing the need to be involved in counseling programmes, in order to discuss psychosocial issues raised by having had cervical cancer [15].

In this context, it emerges an urgent need to identify those women at risk for persistent emotional distress. In particular, we observed that ECC patients who were not menopausal at time of diagnosis showed worse anxiety scores. Furthermore, in LACC cases, low educational level and living status not alone were associated with higher anxiety scores. As explanation to the observed association between the living not alone and higher anxiety levels, we can infer that, those cancer patients, who lives in a family context, could have to cope with fear of being less able to sustain major responsibilities from children management and partner relationship. Therefore, it has to be emphasized that prevention or reduction of anxiety levels would require social and family interventions.

As far as QoL issues are concerned, a gradual, progressive improvement of GHS was observed within the first year from diagnosis, with stable levels at 24-month evaluation, suggesting that cervical cancer patients require a relatively brief time interval to come and accommodate with their illness, adjusting personal internal standard for QoL measures.

As reported in our preliminary experience [16], lymphedema and menopausal symptoms emerged as the most important, long term parameters affecting patients QoL. The administration of radical pelvic surgery combined with radiotherapy plays a crucial role in the development of these symptoms, as also sustained by the close temporal association between the emergence of poor BI scores and the employment of chemoradiation in the group of LACC patients. Furthermore, the extent and persistence of QoL deterioration in women with lymphedema and menopausal symptoms emphasize the need to triage cervical patients to dedicated multidisciplinary teams, during the early phase after completion of primary treatment.

Radical pelvic surgery and chemoradiation are obviously associated with a significant impairment of sexual functioning in cervical cancer patients [4,12,13]. However, we observed a clinically relevant improvement of sexual activity scores over time, regardless of disease extent. Reasons supporting our findings could be the introduction of more tailored procedures in surgical management [31], and also the lack of brachytherapy which resulted in a lower dose of total radiation to genital tract, compared to conventional approaches. On the other hand, it has to be emphasized that, despite a similar trend of recovery, women with LACC showed significantly lower levels of sexual activity compared to ECC patients (Figure 3).

Conclusions

In conclusion, our experience revealed a gradual improvement of emotional distress and QoL issues during the first 2 years after diagnosis of cervical cancer, with the exception of LY and MS symptoms. It is conceivable that long-term improvement of emotional issues could be due mainly due to a higher patient confidence in the successful management of disease. However, it has to be acknowledged that also psychological mechanisms of coping and adaptation may contribute to time interval and extent of resumption from acute emotional disruption. The relative lack of association in multivariate analysis between independent variables and emotional distress, underlines that each patient exerts over time her own personal capabilities to rescue over time form anxiety and QoL deterioration.

A prospective study (IRIS-2, I.R.I.S., http://www.iris-og-com) is going to be launched in our Institution to assess the impact of early and long term psychological interventions on emotional and QoL distress, as well as on immune functions in cervical cancer patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GM: contributed to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the results, drafting of the final manuscript. MP: contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results, drafting of the final manuscript, and preparation of table and figures. GFu: contributed to the data collection and table and figures preparation. LV: contributed to the data collection and table and figures preparation. ST: contributed to the data collection and table and figures preparation. LPA: contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results, drafting of the final manuscript. GS: contributed to the conception, design of the study, interpretation of the results, drafting of the final manuscript. GFe: contributed to the conception, design of the study, interpretation of the results, drafting of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Giovanna Mantegna, Email: giovanna.mantegna@rm.unicatt.it.

Marco Petrillo, Email: afpetrillo@libero.it.

Gilda Fuoco, Email: gildafuoco@gmail.com.

Laura Venditti, Email: laura.venditti@gmail.com.

Serena Terzano, Email: serena.terzano@gmail.com.

Luigi Pedone Anchora, Email: luigi.us@hotmail.it.

Giovanni Scambia, Email: giovanni.scambia@rm.unicatt.it.

Gabriella Ferrandina, Email: gabriella.ferrandina@libero.it.

Acknowledgments

No funding or persons are to be acknowledged.

References

- Vistad I, Fossa SD, Dahl AA. A critical review of patient-rated quality of life studies of long-term survivors of cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:563–572. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase DM, Watanabe T, Monk BJ. Assessment and significance of quality of life in women with gynecologic cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6:1279–1287. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juraskova I, Butow P, Robertson R, Sharpe L, McLeod C, Hacker N. Post-treatment sexual adjustment following cervical and endometrial cancer: a qualitative insight. Psycho-Oncol. 2003;12:267–279. doi: 10.1002/pon.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Bae DS, Nam JH, Park CT, Cho CH, Lee JM, Lee MK, Kim SH, Park SM, Yun YH. Quality of life and sexual problems in cervical cancer survivors. Cancer. 2007;110:2716–2725. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korfage IJ, Essink-Bot ML, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse L, Kruitwagen R, van Ballegooijen M. Health-related quality of life in cervical cancer survivors: a population-based survey. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:1501–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.06.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DW, McCartney CF, Nemeroff CB, Raft D, Quade D, Golden RN, Haggerty JJ Jr, Holmes V, Simon JS, Droba M. Depression in women treated for gynaecological cancer: clinical and neuroendocrine assessment. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:447–452. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain EN, Kohorn EI, Quinlan DM, Schwartz PE, Latimer K, Rogers L. Psychosocial reactions to the diagnosis of gynecologic cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;62:635–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distefano M, Riccardi S, Capelli G, Costantini B, Petrillo M, Ricci C, Scambia G, Ferrandina G. Quality of life and psychological distress in locally advanced cervical cancer patients administered pre-operative chemoradiotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandina G, Margariti PA, Smaniotto D, Petrillo M, Salerno MG, Fagotti A, Macchia G, Morganti AG, Cellini N, Scambia G. Long-term analysis of clinical outcome and complications in locally advanced cervical cancer patients administered concomitant chemoradiation followed by radical surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemoradiotherapy for Cervical Cancer Meta-analysis Collaboration (CCCMAC) Reducing uncertainties about the effects of chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer: individual patient data meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010. p. CD008285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Weisman AD, Worden JW. The existential plight in cancer: significance of the first 100 days. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1976;7:1–15. doi: 10.2190/UQ2G-UGV1-3PPC-6387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frumovitz M, Sun CC, Schover LR, Munsell MF, Jhingran A, Wharton JT, Eifel P, Bevers TB, Levenback CF, Gershenson DM, Bodurka DC. Quality of life and sexual functioning in cervical cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7428–7436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greimel ER, Winter R, Kapp KS, Haas J. Quality of life and sexual functioning after cervical cancer treatment: a long-term follow-up study. Psycho-Oncol. 2009;18:476–482. doi: 10.1002/pon.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Ohno T, Noguchi W, Matsuda A, Matsushima E, Kato S, Tsujii H. Psychological distress and quality of life in cervical cancer survivors after radiotherapy: do treatment modalities, disease stage, and self-esteem influence outcomes? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1264–1268. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a3e124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel L, DeAlba I, Habbal R, Kluhsman BC, Fairclough D, Krebs LU, Anton-Culver H, Berkowitz R, Aziz N. Quality of life in long-term cervical cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:310–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandina G, Mantegna G, Petrillo M, Fuoco G, Venditti L, Terzano S, Moruzzi C, Lorusso D, Marcellusi A, Scambia G. Quality of life and emotional distress in early stage and locally advanced cervical cancer patients: a prospective, longitudinal study. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandina G, Legge F, Fagotti A, Fanfani F, Distefano M, Morganti A, Cellini N, Scambia G. Preoperative concomitant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer: safety, outcome and prognostic measures. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:S127–S132. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legge F, Margariti PA, Lucidi A, Macchia G, Petrillo M, Iannone V, Carone V, Morganti AG, Scambia G, Ferrandina G. Completion surgery after concomitant chemoradiation in obese women with locally advanced cervical cancer: Evaluation of toxicity and outcome measures. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:166–173. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.698753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandina G, Lucidi A, Paglia A, Corrado G, Macchia G, Tagliaferri L, Fanfani F, Morganti AG, Valentini V, Scambia G. Role of comorbidities in locally advanced cervical cancer patients administered preoperative chemoradiation: impact on outcome and treatment-related complications. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini M, Musso M, Viterbori P, Bonci F, Del Mastro L, Garrone O, Venturini M, Morasso G. Detecting psychological distress in cancer patients: validity of the Italian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Support Care Cancer. 1999;7:121–127. doi: 10.1007/s005200050241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greimel ER, Kuljanic Vlasic K, Waldenstrom AC, Duric VM, Jensen PT, Singer S, Chie W, Nordin A, Bjelic Radisic V, Wydra D. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Group. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality-of-Life questionnaire cervical cancer module: EORTC QLQ-CX24. Cancer. 2006;107:1812–1822. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, Martyn St-James M, Fayers PM, Brown JM. Evidence-based guidelines for determination of sample size and interpretation of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:89–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:139–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringash J, O'Sullivan B, Bezjak A, Redelmeier DA. Interpreting clinically significant changes in patient-reported outcomes. Cancer. 2007;110:196–202. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutgendorf SK, Anderson B, Ullrich P, Johnsen EL, Buller RE, Sood AK, Sorosky JI, Ritchie J. Quality of life and mood in women with gynecologic cancer: a one year prospective study. Cancer. 2002;94:131–140. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RW, Quinlivan JA. Preventing anxiety and depression in gynaecological cancer: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2002;109:386–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Ninomiya M, Maruta S, Hosonuma S, Nishigaya Y, Kobayashi Y, Kiguchi K, Ishizuka B. Psychological characteristics of Japanese gynecologic cancer patients after learning the diagnosis according to the hospital anxiety and depression scale. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:800–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz D, Emery CF, Glaser R, Crespin T, Carson WE 3rd. Distress reduction from a psychological intervention contributes to improved health for cancer patients. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:953–961. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dursun P, Ayhan A, Kuscu E. Nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy for cervical carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;70:195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]