Abstract

Background

Estrogen is believed to play an important role in the central nervous system (CNS) and exert a protective role against schizophrenia. Estrogen receptor alpha (ESRα) mediates the biological action of estrogen. Rs2234693 and rs9340799, single nucleotide polymorphisms of ESRα, may be related to many psychiatric disorders, while their association with schizophrenia has not been clarified.

Methods

Genotypes rs2234693 and rs9340799 were detected in 303 schizophrenic patients and 292 healthy controls in a Chinese population. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) was used to estimate symptoms and therapeutic effects. The association of these polymorphisms with schizophrenia and clinical characteristics was analyzed by the chi-square test, analysis of variance, and others.

Results

The distribution of genotypes and allele frequencies of rs2234693 and rs9340799 exhibited no significant differences between patients and controls, while haplotypes consisting of these polymorphisms had significant differences. For 2234693, T-allele carriers had an earlier age at onset. CC-homozygote carriers had a higher general psychopathology score and its percentage reduction in male and paranoid patients, respectively. CC-homozygote carriers had a higher tension (G4) and poor impulse control (G14) score, mainly in paranoid patients. Furthermore, patients with the CC homozygote had higher reductions of G4 and G14 scores when treated by aripirazole and risperidone, respectively.

Conclusions

Haplotypes consisting of these two polymorphisms in ESRα may be strongly associated with schizophrenia. The rs2234693 was related to age at onset, general psychopathology, G4 and G14 symptoms, even the therapeutic effect in different groups.

Keywords: Estrogen receptor, Polymorphism, Association, Schizophrenia, Age at onset, Symptom, Therapeutic effect

Background

Schizophrenia is a severe and polygenic inherited disease with an incidence of appropriately 1% worldwide [1]. The mechanism of its pathogenesis has been explored in various studies, but it is still undefined. Some psychiatric clinical data show the obvious differences between the two genders in age at onset, symptomatology, and prognosis for schizophrenia [2]. The peak age of onset for females is 4 to 6 years later than that of males [3]. Furthermore, affective symptoms are more prevalent in female patients [4], while functional impairment is more likely present in males [5]. In addition, female patients have a better overall prognosis than males [6].

The gender differences might be explained by the modern estrogen hypothesis, which presupposes that estrogen exerts a protective activity against schizophrenia [7]. The ovarian steroid hormone estrogen plays an important role in biological processes, and its influence on the CNS has been fully described [8,9]. The estrogenic level fluctuation was in different genders and ages, which has long been demonstrated [10,11]. On the other hand, patients with an older age at onset may live with a decreasing estrogenic level [10]. The cognitive abilities of patients with higher estrogenic levels are better than those with lower levels [12]. Furthermore, a previous study has found that the positive effect of estrogen treatment with standardized antipsychotic medication may be effective in replacement therapy for female schizophrenia [13].

The biological actions of estrogen are manifest through estrogen receptors, which belong to a large family of nuclear receptors [14]. Two estrogen receptors have been identified, designated as estrogen receptor alpha (ESRα) and estrogen receptor beta (ESRβ) [14]. ESRα localizes in chromosome 6 and encodes a 6.8-kilobase mRNA containing eight exons, finally becoming transformed into diverse proteins with different binding abilities [15], while ESRβ localizes in chromosome 14 and encodes a protein which is 97% and 59% homologous in the amino acid sequence with ESRα in DNA- and hormone-binding domains, respectively [16]. The distribution and biological activation of the two estrogen receptors in the nervous system are generally consistent [17], but ESRα appears to be responsible for most of the known estrogenic activations [18].

Recent studies have determined that the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of ESRα might be related to many disorders, including osteoporosis [19], stroke [20], and Alzheimer’s disease [21]. Interestingly, other studies have indicated that the SNPs in ESRα are also associated with many psychiatric disorders. A case–control study showed a significant association of ESRα SNP rs2234693 with major depression disorder [22]. Furthermore, the ESRα haplotypes created by rs2234693 and rs9340799 polymorphisms increased the likelihood of having an anxiety disorder but not a depressive disorder [23]. Schizophrenia is a highly heterogeneous disease effected by multiple genes that generally belong to different hypothesis for the etiology of this disorder [24], such as the dopamine D2 receptor gene, a key member of dopamine hypothesis for schizophrenia, whose polymorphisms are associated with schizophrenia [25]. Based on the estrogen hypothesis, Weickert et al. [26] reported that rs2234693 was related to ESRα mRNA levels, associating with schizophrenia in their African American case–control sample, but other studies [27,28] had different point of view.

Overall, the conclusions of association between ESRα and schizophrenia are inconsistent. The purpose of this study was to determine whether there exists an association of ESRα polymorphisms with schizophrenia in our samples. Furthermore, we also examined the association of the polymorphisms with clinical characteristics including age at onset, symptoms, and therapeutic effects.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Three hundred three inpatients with schizophrenia (male/female = 152/151) were recruited from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical University. The patients were diagnosed in accordance with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria by at least two experienced psychiatrists on the basis of structured clinical interviews and medical records. Patients were treated by monotherapy with aripiprazole (Abilify) (n = 146) or risperidone (Risperdal) (n = 157) after a washout period of 6 weeks. The average daily dose of antipsychotics for each patient was 4.9 ± 1.6 mg/day in risperidone equivalents.

Two hundred ninety-two healthy controls (male/ female = 146/146) without a psychiatric history (including personal and family) and complex disorders including diabetes, hypertension, immunological mediated disease, and tumors were selected from local Henan Province. All participators in the study were Chinese Hans. The mean age of the case group was 29.99 ± 8.86, and that of the control group was 30.92 ± 9.12. No significant differences in sex or age between the two groups existed.

All subjects consented to participate in the study after reviewing the informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical University.

Clinical measures

The age at which the individual first experienced a diagnosis or symptoms of schizophrenia was defined as the age at onset of schizophrenia. To assess the psychopathologic severity of the patients, PANSS (including 3 subscales, positive symptom, negative symptom and general psychopathology symptom) was used by four experienced psychiatrists. The severity of each symptom was scored with one of seven grades (1 = absent, 2 = minimal, 3 = mild, 4 = moderate, 5 = moderate severe, 6 = severe, 7 = extreme). The PANSS scores at week 0 were regarded as baseline. To evaluate the therapeutic effect over 6 weeks, the percentage reduction in PANSS score and reduction in PANSS subscore were used. All the psychiatrists had been trained in the use of PANSS before the study.

Genotyping

Global genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral leucocytes using standard protocols. The ESRα fragment, including rs2234693 and rs9340799 polymorphisms, was amplified by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the following primers: Sense: 5′-CCTTTCTGTGTTCCTCTTCT-3′; antisense: 5′-TACCTCTTGCCGTCTGTT-3′. PCR amplification was performed in a 25-μL reaction volume containing 10 × PCR buffer (supplied by Tian Gen) 2.5 μL, dNTP mix (2.5 mM, supplied by Tian Gen) 0.5 μL, sense primer (10 μM, supplied by Genewiz) 1 μL, antisense primer (10 μM, supplied by Genewiz) 1 μL, genomic DNA 1 μL, Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μL, supplied by Tian Gen) 0.4 μL, and sterile deionized water 18.6 μL. After initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, the ingredients were mixed at 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 54 s, and a final elongation was done at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR product was cleaved using Pvu II and Xba I restriction enzymes (supplied by Thermo) at 37°C for 2 h, then analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels. Genotypes for rs2234693 and rs9340799 polymorphisms were identified by two investigators independently.

Statistical analysis

Hardy Weinberg equilibrium was performed using Haploview 4.1 to examine the genotype distributions of these two polymorphisms of ESRα. The strength of linkage disequilibrium between the two SNPs was determined using D’ and r2 algorithm testing by SHEsis online software (http://analysis2.bio-x.cn/myAnalysis.php) [29]. The Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test for analysis of survival were used to examine the association of age at onset with the two polymorphisms [30]. The difference in genotypic and allelic frequency distribution between case and control groups was estimated by SPSS software 18.0 using the Pearson chi-square (χ2) test. Haplotype analysis for the ESRα was performed using SNPStats software on line (http://bioinfo.iconcologia.net/snpstats) [31]. The relationship between the polymorphisms and the clinical variables was also analyzed by SPSS 18.0 using one-way ANOVA or rank sum test. In addition, to control for the possible confounding effect of gender and therapeutic drugs, stratification of the samples was repeated by those factors, respectively [32]. The Bonferroni correction was applied to avoid a type I error in the multiple tests. A power analysis was performed using the Genetic Power Calculator [33]. All statistical analyses were two-tailed, and the level of statistical significance was adjusted to p < 0.05.

Results

Genotype identification

The PCR products were 899 base pairs. The three genotypes resulting from digestion with Pvu II were CC (899 bp), CT (899, 630, 269 bp), and TT (630, 269 bp). Similarly, three genotypes were yielded from digestion with Xba I: GG (899 bp), AG (899, 675, 224 bp), and AA (675, 224 bp). The codominant model was a combination of separate genotypes of CC, CT, and TT for rs2234693, and AG, GG, and GG for rs9340799. The dominant model consisted of a C-allele carrier and TT homozygote for rs2234693, and a G-allele carrier and AA homozygote for rs9340799. Furthermore, the recessive model was formed by a T-allele carrier and CC homozygote for rs2234693, and an A-allele carrier and GG homozygote for rs9340799.

Association of SNPs with schizophrenia

The distributions of genotypes and allele frequencies of the ESRα polymorphisms for all, male, and female groups were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The genotype and allele distribution of rs2234693 had no significant differences when comparing cases and controls, even in the subgroups stratified by gender (Table 1). No significant differences were demonstrated for the genotype and allele distribution of rs9340799 in comparing cases and controls. But when stratified according to gender, a nominal difference was found for genotype distribution and a significant difference for allele distribution in male cases with schizophrenia and male controls (corrected p = 0.05 and p = 0.02, respectively), but no significant differences when comparing for females (Table 1). This study had the power of 0.739 overall.

Table 1.

Association analysis of SNPs with schizophrenia

| dbSNP ID | Group |

Cases |

Controls |

p-value |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | HWE ( p ) | Genotype | MAF | N | HWE ( p ) | Genotype | MAF | Genotype | Allele | ||||||

| rs2234693 |

|

|

|

TT |

TC |

CC |

|

|

|

TT |

TC |

CC |

|

|

|

| |

All |

303 |

0.55 |

109 |

150 |

44 |

0.15 |

292 |

0.71 |

111 |

141 |

40 |

0.14 |

0.868 |

0.612 |

| Male |

152 |

0.86 |

63 |

71 |

18 |

0.12 |

146 |

0.46 |

60 |

71 |

15 |

0.10 |

0.894 |

0.876 |

|

| Female |

151 |

0.51 |

46 |

79 |

26 |

0.17 |

146 |

1.00 |

51 |

70 |

25 |

0.17 |

0.692 |

0.574 |

|

| rs9340799 |

|

|

|

AA |

AG |

GG |

|

|

|

AA |

AG |

GG |

|

|

|

| All |

303 |

1.00 |

194 |

97 |

12 |

0.04 |

292 |

0.85 |

189 |

93 |

10 |

0.03 |

0.938 |

0.789 |

|

| Male |

152 |

0.50 |

91 |

51 |

10 |

0.07 |

146 |

0.53 |

104 |

40 |

2 |

0.01 |

0.025 |

0.010 |

|

| Female | 151 | 0.37 | 103 | 46 | 2 | 0.01 | 146 | 1.00 | 85 | 53 | 8 | 0.05 | 0.057 | 0.031 | |

Boldface letters represent that the Bonferroni corrected p-values are still less than 0.05.

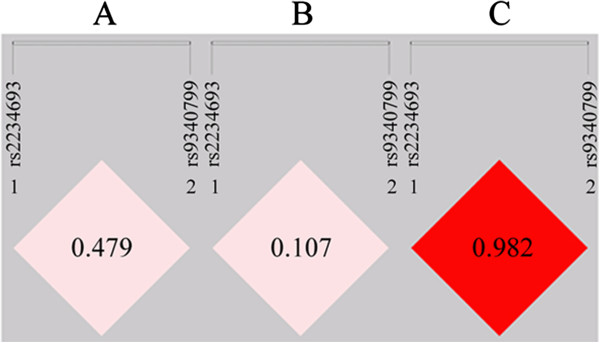

Association of haplotypes with schizophrenia

In all samples, a modest linkage disequilibrium was observed between rs2234693 and rs9340799 (D’ = 0.479, r2 = 0.089). A strong linkage disequilibrium was found in the analysis of normal controls (D’ = 0.982, r2 = 0.380), but not for patients with schizophrenia (D’ = 0.107, r2 = 0.002) (Figure 1). A haplotype was constructed from rs2234693 and rs9340799. Four haplotypes were recognized after combining with the two polymorphisms. T-A was the most prevalent haplotype, with frequencies of 0.5502, 0.5633, and 0.5403 in all, male, and female subjects, respectively, followed by the C-A, C-G, and T-G haplotypes (Table 2). In all and female subjects, the frequencies of C-A, C-G, and T-G showed a significant difference between cases and controls, whereas in the male subjects, only C-A was significantly different (corrected p = 0.0036). In addition, significant associations of global haplotype with schizophrenia showed up in both males and females (corrected p < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Linkage disequilibrium among rs2234693 and rs9340799. A, linkage disequilibrium in all samples with 0.479 for D’; B, linkage disequilibrium in patients with 0.107 for D’; C, linkage disequilibrium in controls with 0.982 for D’.

Table 2.

The rs2234693-rs9340799 haplotype association analysis

| Group | rs2234693 | rs9340799 |

Frequencies |

OR (95% CI) | p-value | Global haplotype association | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | All | ||||||

| All |

T |

A |

0.478 |

0.620 |

0.550 |

1 |

|

< 0.0001 |

| C |

A |

0.323 |

0.187 |

0.253 |

0.45 (0.33 - 0.61) |

< 0.0001 |

||

| C |

G |

0.070 |

0.191 |

0.133 |

1.94 (1.23 - 3.06) |

0.0046 |

||

| T |

G |

0.130 |

0.002 |

0.064 |

0.01 (0.00 - 0.10) |

< 0.0001 |

||

| Male |

T |

A |

0.473 |

0.654 |

0.563 |

1 |

|

< 0.0001 |

| C |

A |

0.294 |

0.195 |

0.244 |

0.47 (0.30 - 0.73) |

0.0009 |

||

| C |

G |

0.058 |

0.151 |

0.105 |

1.75 (0.83 - 3.69) |

0.14 |

||

| T |

G |

0.176 |

0.000 |

0.088 |

0.00 (−Inf - Inf) |

1 |

||

| Female | T |

A |

0.490 |

0.585 |

0.540 |

1 |

|

< 0.0001 |

| C |

A |

0.344 |

0.179 |

0.259 |

0.44 (0.28 - 0.68) |

0.0002 |

||

| C |

G |

0.090 |

0.232 |

0.163 |

2.04 (1.18 - 3.53) |

0.012 |

||

| T | G | 0.076 | 0.004 | 0.037 | 0.04 (0.01 - 0.35) | 0.0035 | ||

Boldface letters represent that the Bonferroni corrected p-values are still less than 0.05.

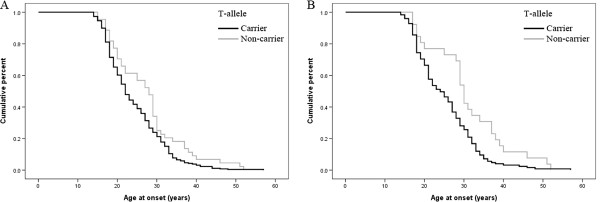

Age at onset analysis

The rs2234693 polymorphism may be related to age at onset in the association analysis of ESRα and initial clinical features of schizophrenia (p = 0.0089) (Figure 2A). The ages at onset of T-allele carriers and those of noncarriers were 24.2 ± 7.4 and 27.5 ± 9.1, respectively. When stratified by gender, the association was more significant in the female cases (p = 0.001, 25.2 ± 6.2, and 31.0 ± 9.8 years for the T-allele carriers and noncarriers, respectively) (Figure 2B), but not in the male cases (p = 0.663). For rs9340799, no significant association was found in any groups.

Figure 2.

The Kaplan-Meier plot showing the age at onset of schizophrenia with T allele. A, the earlier age at onset in all cases carrying the T allele of rs2234693; B, the earlier age at onset in female cases carrying the T allele of rs2234693.

Association of SNPs with clinical symptoms

Of 201 patients with schizophrenia enrolled in this analysis, the distributions of rs2234693 (CC = 31, CT = 99, and TT = 71) and rs9340799 (AA = 133, AG = 60 and GG = 8) genotypes were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p = 0.77 and p = 0.65, respectively). Clinical symptoms, including the baseline of total, positive symptom, negative symptom, and general psychopathology symptom were analyzed in this study first. There was no significant difference in total, positive, or negative scores when comparing diverse genotypes of rs2234693 (data not shown). However, in comparing the general psychopathology scores, the difference was significant among TT (40.49 ± 5.81), TC (43.22 ± 5.37), and CC (45.58 ± 7.09) genotypes of rs2234693 only in male patients with schizophrenia (Table 3). Furthermore, the subscores of general psychopathology symptoms were examined in all stratified patients. The CC genotype carriers of rs2234693 had much higher scores (3.35 ± 1.56) than T-allele carriers (TC, 2.40 ± 1.45; TT, 2.39 ± 1.47) in poor impulse control (G14), and the difference still existed in the paranoid patients (Table 3). In addition, the tension (G4) of general psychopathology subscores was significant higher in the CC (3.21 ± 1.53) genotype carriers than in the T-allele carriers (TC, 2.55 ± 1.47; TT, 2.18 ± 1.30), only in the paranoid patients (Table 3). None of the clinical variables of the baseline symptoms was significantly different between the various genotypes of rs9340799 (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Table 3.

Association analysis of rs2234693 with the base line of symptoms

| Group | Characteristic |

Codominant |

Dominant |

Recessive |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/χ2 | p-value | F/χ2 | p-value | F/χ2 | p-value | ||

| All |

General psychopathology score |

0.671 |

0.512 |

0.186 |

0.666 |

1.345 |

0.248 |

| Tension score |

2.407 |

0.093 |

0.031 |

0.859 |

4.561 |

0.034 |

|

| Poor impulse control score |

5.506 |

0.005 |

1.132 |

0.289 |

11.065 |

0.001 |

|

| Male |

General psychopathology score |

4.345 |

0.016 |

1.476 |

0.228 |

4.303 |

0.041 |

| Tension score |

0.915 |

0.405 |

0.011 |

0.915 |

1.733 |

0.191 |

|

| Poor impulse control score |

3.367 |

0.039 |

0.073 |

0.788 |

5.505 |

0.021 |

|

| Female |

General psychopathology score |

0.543 |

0.582 |

1.069 |

0.303 |

0.025 |

0.875 |

| Tension score |

1.469 |

0.235 |

0.007 |

0.934 |

2.763 |

0.099 |

|

| Poor impulse control score |

3.458 |

0.035 |

3.244 |

0.074 |

5.558 |

0.020 |

|

| Paranoid | General psychopathology score |

1.430 |

0.242 |

0.035 |

0.853 |

2.762 |

0.098 |

| Tension score |

5.208 |

0.006 |

0.341 |

0.560 |

7.968 |

0.005 |

|

| Poor impulse control score | 5.613 | 0.004 | 0.718 | 0.398 | 11.268 | 0.001 | |

Boldface letters represent that the Bonferroni corrected p-values are still less than 0.05.

Association of SNPs with therapeutic effect

The associations of rs2234693 with general psychopathology, tension (G4), and poor impulse control (G14) score of PANSS have been verified above. Thus, we further investigated whether rs2234693 is related to improvement in these symptoms after 6 weeks of antipsychotic treatment. Thereby, the percentage reduction of general psychopathology score was higher in the C-allele carriers than TT-homozygote carriers in female (CC+CT, 0.456 ± 0.270; TT, 0.327 ± 0.216) and paranoid (CC+CT, 0.464 ± 0.241; TT, 0.367 ± 0.213) patients with schizophrenia (Table 4). Furthermore, the reduction of G14 was higher in the CC-homozygote carriers than in the C-allele carriers overall (CC, 1.900 ± 1.795; CT+TT, 1.020 ± 1.287), male (CC, 2.170 ± 2.125; CT+TT, 1.040 ± 1.272), and paranoid (CC, 2.000 ± 1.888; CT+TT, 0.990 ± 1.289) patients with schizophrenia (Table 4). In addition, to control for possible confounding effects of the therapeutic drug, the patients were stratified by antipsychotic drug. Interestingly, the CC-homozygote carriers (1.800 ± 1.265) showed a greater G4 reduction than did the CT (0.900 ± 1.357) and TT (0.550 ± 0.905) genotype carriers after treatment by aripirazole, while CC-homozygote carriers (2.380 ± 1.628) had more G14 reduction than did CT (1.350 ± 1.336) and TT (0.860 ± 1.332) genotype carriers after treatment by risperidone (Table 4). None of the clinical variables of the reductions was significantly different between genotypes of rs9340799 (Additional file 2: Table S2).

Table 4.

Association analysis of rs2234693 with therapeutic effects in 6-week therapy

| Group | Characteristic |

Codominant |

Dominant |

Recessive |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/X2 | p-value | F/X2 | p-value | F/X2 | p-value | ||

| All |

Percentage reduction in general psychopathology score |

2.964 |

0.054 |

5.259 |

0.023 |

0.003 |

0.955 |

| |

Reduction in tension score |

1.879 |

0.155 |

0.693 |

0.406 |

3.718 |

0.055 |

| |

Reduction in poor impulse control score |

1.928 |

0.165 |

4.153 |

0.043 |

10.721 |

0.001 |

| Male |

Percentage reduction in general psychopathology score |

0.290 |

0.749 |

0.508 |

0.478 |

0.246 |

0.621 |

| |

Reduction in tension score |

1.482 |

0.233 |

0.599 |

0.441 |

2.938 |

0.090 |

| |

Reduction in poor impulse control score |

0.157 |

0.692 |

0.330 |

0.567 |

6.657 |

0.012 |

| Female |

Percentage reduction in general psychopathology score |

3.784 |

0.026 |

6.168 |

0.015 |

0.123 |

0.727 |

| |

Reduction in tension score |

0.562 |

0.572 |

0.148 |

0.701 |

1.129 |

0.290 |

| |

Reduction in poor impulse control score |

3.946 |

0.022 |

5.604 |

0.020 |

4.514 |

0.036 |

| Paranoid |

Percentage reduction in general psychopathology score |

3.264 |

0.041 |

6.567 |

0.011 |

0.636 |

0.426 |

| |

Reduction in tension score |

2.339 |

0.100 |

0.223 |

0.637 |

4.670 |

0.032 |

| |

Reduction in poor impulse control score |

1.163 |

0.281 |

3.442 |

0.065 |

10.756 |

0.001 |

| Aripirazole |

Percentage reduction in general psychopathology score |

1.321 |

0.272 |

2.316 |

0.132 |

1.148 |

0.287 |

| |

Reduction in tension score |

5.721 |

0.005 |

4.920 |

0.029 |

9.731 |

0.002 |

| |

Reduction in poor impulse control score |

1.019 |

0.365 |

0.538 |

0.465 |

1.989 |

0.162 |

| Risperidone |

Percentage reduction in general psychopathology score |

2.213 |

0.115 |

1.797 |

0.183 |

1.274 |

0.262 |

| |

Reduction in tension score |

0.591 |

0.555 |

1.136 |

0.289 |

0.295 |

0.588 |

| Reduction in poor impulse control score | 6.632 | 0.002 | 6.035 | 0.016 | 10.423 | 0.002 | |

Boldface letters represent that the Bonferroni corrected p-values are still less than 0.05.

Discussion

We conclude that the ESRα rs2234693 and rs9340799 polymorphisms do not substantially contribute to susceptibility of schizophrenia, although a modest association was detected in males only for rs9340799. The results are nearly consistent with most previous studies. This difference may be due to these reasons: on one hand, the subjects in the study of Weickert were African American [26] only, while others were East Asians [28,34] or southern Europeans [27]. Susceptibility to the disease and distribution of the genotype for rs2234693 were distinctly different in these subjects (data was from International HapMap Project). On the other hand, the sample size and test power between these studies were difference. Interestingly, the haplotypes in the gene may increase the risk of schizophrenia. C-A rarely emerges with the extremely high frequency of approximately 25%, and it may contribute to schizophrenia. It is noteworthy that C-G may play the role of protective haplotype, especially in females. It is also meaningful that T-G and C-G may act only on females, not males.

The age of onset has been considered the single most valuable characteristic of schizophrenia that may yield a clue to its origin [30]. A genomewide linkage study by Cardno et al. [35] has confirmed a genetic contribution to the age at onset of schizophrenia. This was the first time that significant associations of ESRα polymorphisms with age at onset of schizophrenia have been demonstrated. But in the study by Ouyang et al. [34], this association was not clearly verified. This inconsistency might be due to differences in population and in the definition of age at onset. In the present study, it is interesting that the T-allele of rs2234693 may relate to earlier pathogenesis of schizophrenia in all and female patients, not in males independently. Evidence that female schizophrenics are more easily influenced by inheritance than males may contribute to the gender difference [36].

Although many genes do not alter susceptibility to schizophrenia, they may affect clinical features [37,38]. A study by Alonso et al. [32] verified that rs34535804 and five SNP haplotypes in ESRα were associated only with the psychopathic symptoms contamination obsessions and cleaning compulsions. In our study, we hypothesize that all, male, and paranoid schizophrenic patients with the T-allele had generally poor impulse control, as well as both tension and poor impulse control symptoms, respectively, suggesting an association of these psychopathic symptoms with rs2234693 of ESRα in special populations. In the therapeutic effect analysis, female and paranoid patients with the CC homozygote had a superior therapeutic effect in general psychopathology symptom after 6 weeks. Notably, we found that aripriazole was more effective in treating tension symptoms in patients with the CC homozygote, while risperidone controlled poor impulse symptoms, again, in patients having the CC homozygote. These findings suggest that T-allele protects against the onset of these symptoms, especially in general psychopathology, tension, and poor-impulse control psychopathic symptoms. Furthermore, CC-homozygote carriers seem to be more sensitive to antipsychotic treatment. It is also worth noting that two polymorphisms are closely located on the ESRα gene, but this study has demonstrated that rs2234693 is not linked in disequilibrium with rs9340799 in patients with schizophrenia. This explains why only rs2234693 without rs9340799 is associated with clinical characteristics of schizophrenia.

ESRα is markedly different from other neurotransmitter receptors in that it may influence mood, cognition, and synaptogenesis and be involved in neuroprotective effects [9,39]. ESRα, as a ligand-dependent transcription factor, is widely distributed in the amygdala-hippocampal area, periamygdaloid cortex, and posterior cortical nucleus of the brain [40], especially in several limbic structures, suggesting its relationship with the above-mentioned processes [41]. Furthermore, in the CNS, ESRα binds its specific ligand estrogen to influence various neurotransmitter systems such as dopamine, serotonin (5-HT), and norepinephrine. These phenomena may be responsible for the relation between ESRα and many psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia [40]. A previous review by Herrington et al. [42] has summarized the associations of ESRα polymorphisms with mood and cognition dysfunction, suggesting a strong relationship between them. We conclude that the association mechanism of ESRα variants with psychiatric characteristics may involve the estrogen-estrogen receptor effect, above. Whether our results can explain this mechanism needs further study.

In this study, we found a significant association of ESRα polymorphism with age at onset, general psychopathology symptoms, and, for the first time, the therapeutic effects in schizophrenia, but limitations also existed. Firstly, as only two polymorphisms were selected for analysis, they do not represent the whole gamut of the human ESRα, further studies should be done to analyze more variants. Secondly, not all the patients were included in the association analysis of clinical variables due to the finite clinical data. Thirdly, because the structured clinical interviews were difficult and time-consuming, our sample size was inadequate and could easily have led to false positive or negative results. Fourthly, although stratified analyses were performed, more subtle and stratified analyses should be used in further studies. Finally, whether ESRα variants can be considered as genetic markers to determine the risk or prognosis of schizophrenia needs further exploration.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the haplotypes consisting of rs2234693 and rs9340799 in ESRα are mainly associated with schizophrenia. The rs2234693 polymorphism is related to the age at onset of schizophrenia. Notably, ESRα may affect the general psychopathology symptoms and its improvement in specific patients with schizophrenia. Additionally, we noticed that tension and poor impulse control symptoms were improved more significantly in CC-homozygote carriers after treatment by aripirazole and risperidone, respectively.

Abbreviations

CNS: Central nervous system; ESRα: Estrogen receptor alphap; PANSS: Positive and negative syndrome scale; ESRβ: Estrogen receptor beta; SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Author SW, WL, and LL designed the study. SW wrote the protocol and the first draft of the manuscript. Author SW and XW finished the biological experiments. Author WL managed the literature searches and analyses. Author XS and HZ undertook the statistical analysis. Author JZ, YY, and GY collected clinical data. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Association analysis of rs9340799 with the base line of symptoms.

Association analysis of rs9340799 with therapeutic effects in 6-week therapy.

Contributor Information

Shuai Wang, Email: wshuai86@126.com.

Wenqiang Li, Email: lwq781603@163.com.

Jingyuan Zhao, Email: xiufei2004@yahoo.com.cn.

Hongxing Zhang, Email: zhx166666@163.com.

Yongfeng Yang, Email: yongfeng_200888@126.com.

Xiujuan Wang, Email: wang.xiujuan314@163.com.

Ge Yang, Email: heyi8686@126.com.

Luxian Lv, Email: lvx928@126.com.

Acknowledgments

We thank Weihua Yue (Peking University, Beijing, China) and Yi He (Sichuan University, Chengdu, China), who assisted with the preparation and proof-reading of data and the manuscript. Funding for this study was provided by the Postgraduate Scientific Research Innovative Program of Xinxiang Medical University (No. YJSCX201109Z to W-S), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 81071091 to L-XL; NO. 81201040 to L-WQ), the Natural Science Foundation of Henan (NO. 112300413226 to L-XL, NO. 122300413212 to L-WQ), and the Plan For Scientific Innovation Talent of Henan Province (NO. 124200510019 to L-XL).

References

- Van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374:635–645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DA Leung MD, Chue MRC, Psych DP. Sex differences in schizophrenia, a review of the literature. Acta Psychiat Scand. 2000;101:3–38. doi: 10.1111/j.0065-1591.2000.0ap25.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle D, Wessely S, Der G, Murray RM. The incidence of operationally defined schizophrenia in Camberwell, 1965–84. Brit J Psychiatry. 1991;159:790–794. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.6.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JM, Link BG. Gender and the expression of schizophrenia. J Psychiat Res. 1988;22:141–155. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(88)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz SK, Miller DD, Oliver SE, Arndt S, Flaum M, Andreasen NC. The life course of schizophrenia: age and symptom dimensions. Schizophr Res. 1997;23:15–23. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(96)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski S, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Mayerhoff D. Gender differences in onset of illness, treatment response, course, and biologic indexes in first-episode schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:698–703. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.5.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriadis S, Seeman MV. The role of estrogen in schizophrenia: implications for schizophrenia practice guidelines for women. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:437–442. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink G. The GW harris lecture steroid control of brain and pituitary function. Exp Physiology. 1988;73:257–293. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1988.sp003145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl SM. Estrogen makes the brain a sex organ. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:421–422. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v58n1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindamer LA, Lohr JB, Harris MJ, Jeste DV. Gender, estrogen, and schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology Bull. 1997;33:221–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer K, Riecher-R A. The influence of age and sex on the onset and early course of schizophrenia. Brit J Psychiatry. 1993;162:80–86. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff AL, Kremen WS, Wieneke MH, Lauriello J, Blankfeld HM, Faustman WO, Csernansky JG, Nordahl TE. Association of estrogen levels with neuropsychological performance in women with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1134–1139. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni J, Riedel A, De Castella AR, Fitzgerald PB, Rolfe TJ, Taffe J, Burger H. Estrogen—a potential treatment for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;48:137–144. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(00)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speroff L. A clinical understanding of the estrogen receptor. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;900:26–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollig A, Miksicek RJ. An estrogen receptor-α splicing variant mediates both positive and negative effects on gene transcription. Mol Endocrinology. 2000;14:634–649. doi: 10.1210/me.14.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosselman S, Polman J, Dijkema R. ERβ: identification and characterization of a novel human estrogen receptor. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00782-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring N, Tantam D, Montague L, Newby D, Black D, Morris J. Gender differences in the incidence of definite schizophrenia and atypical psychosis—focus on negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1991;84:489–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb03182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couse JF, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr Rev. 1999;20:358–417. doi: 10.1210/er.20.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignaszak-Szczepaniak M, Horst-Sikorska W, Dytfeld J, Marcinkowska M, Słomski R, Stajgis M. Association between estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphisms and bone mineral density in Polish female patients with Graves’ disease. Acta Biochim Pol. 2011;58:101–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munshi A, Sharma V, Kaul S, Al-Hazzani A, Alshatwi AA, Manohar VR, Rajeshwar K, Babu MS, Jyothy A. Estrogen receptor [alpha] genetic variants and the risk of stroke in a South Indian population from Andhra Pradesh. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1817–1821. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma SL, Tang NLS, Tam CWC, Lui VWC, Lau ESS, Zhang YP, Chiu HFK, Lam LCW. Polymorphisms of the estrogen receptor α (ESR1) gene and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in a southern Chinese community. Int Psychogeriatrics. 2009;21:977–986. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SJ, Wang YC, Hong CJ, Chiu HJ. Association study of oestrogen receptor [alpha] gene polymorphism and suicidal behaviours in major depressive disorder. Psychiat Genet. 2003;13:19–22. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiemeier H, Schuit S, Den Heijer T, Van Meurs J, Van Tuijl H, Hofman A, Breteler M, Pols H, Uitterlinden A. Estrogen receptor α gene polymorphisms and anxiety disorder in an elderly population. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:806–807. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan JM, Susser E, King M-C. Schizophrenia: a common disease caused by multiple rare alleles. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:194–199. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arinami T, Gao M, Hamaguchi H, Toru M. A functional polymorphism in the promoter region of the dopamine D2 receptor gene is associated with schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:577–582. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.4.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickert CS, Miranda-Angulo AL, Wong J, Perlman WR, Ward SE, Radhakrishna V, Straub RE, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE. Variants in the estrogen receptor alpha gene and its mRNA contribute to risk for schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2293–2309. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorell L, Costas J, Valero J, Gutierrez-Zotes A, Phillips C, Torres M, Brunet A, Garrido G, Carracedo A, Guillamat R. Analyses of variants located in estrogen metabolism genes (ESR1, ESR2, COMT and APOE) and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;100:308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi T, Ikeda M, Kitajima T, Yamanouchi Y, Kinoshita Y, Kawashima K, Okochi T, Okumura T, Tsunoka T, Inada T. Association analysis of functional polymorphism in estrogen receptor alpha gene with schizophrenia and mood disorders in the Japanese population. Psychiat Genet. 2009;19:217–218. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32832cee98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong Y, Lin H. SHEsis, a powerful software platform for analyses of linkage disequilibrium, haplotype construction, and genetic association at polymorphism loci. Cell Res. 2005;15:97–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anttila S, Kampman O, Illi A, Roivas M, Mattila KM, Lassila V, Lehtimäki T, Leinonen E. NOTCH4 gene promoter polymorphism is associated with the age of onset in schizophrenia. Psychiat Genet. 2003;13:61–63. doi: 10.1097/01.ypg.0000056681.82896.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solé X, Guinó E, Valls J, Iniesta R, Moreno V. SNPStats: a web tool for the analysis of association studies. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1928–1929. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso P, Gratacos M, Segalas C, Escaramis G, Real E, Bayés M, Labad J, Pertusa A, Vallejo J, Estivill X. Variants in estrogen receptor alpha gene are associated with phenotypical expression of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Genetic power calculator: design of linkage and association genetic mapping studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:149–150. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang WC, Wang YC, Hong CJ, Tsai SJ. Estrogen receptor [alpha] gene polymorphism in schizophrenia: frequency, age at onset, symptomatology and prognosis. Psychiat Genet. 2001;11:95–98. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200106000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardno AG, Holmans PA, Rees MI, Jones LA, McCarthy GM, Hamshere ML, Williams NM, Norton N, Williams HJ, Fenton I. A genomewide linkage study of age at onset in schizophrenia*. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:439–445. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WJ, Yeh LL, Chang CJ, Lin LC, Rin H, Hwu HG. Month of birth and schizophrenia in Taiwan: effect of gender, family history and age at onset. Schizophr Res. 1996;20:133–143. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanous A, Kendler K. Genetic heterogeneity, modifier genes, and quantitative phenotypes in psychiatric illness: searching for a framework. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:6–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WJ, Kou CG, Yu Y, Sun S, Zhang X, Kosten TR, Zhang XY. Association of Catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphisms with schizophrenia and negative symptoms in a Chinese population. Am J Med Genet B. 2012;159B:370–375. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PS, Simpkins JW. Neuroprotective effects of estrogens: potential mechanisms of action. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2000;18:347–358. doi: 10.1016/S0736-5748(00)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Östlund H, Keller E, Hurd YL. Estrogen receptor gene expression in relation to neuropsychiatric disorders. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;1007:54–63. doi: 10.1196/annals.1286.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Österlund MK, Hurd YL. Estrogen receptors in the human forebrain and the relation to neuropsychiatric disorders. Prog Neurobiology. 2001;64:251–267. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(00)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington DM, Howard TD, Hawkins GA, Reboussin DM, Xu J, Zheng SL, Brosnihan KB, Meyers DA, Bleecker ER. Estrogen-receptor polymorphisms and effects of estrogen replacement on high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in women with coronary disease. New Engl J Med. 2002;346:967–974. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Association analysis of rs9340799 with the base line of symptoms.

Association analysis of rs9340799 with therapeutic effects in 6-week therapy.