Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to determine peri-operative mortality and long-term outcomes in patients undergoing liver transplantation in the US using the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database.

Methods

This study is a retrospective review of liver transplantations (LT) recorded in the UNOS database performed between 1988 and 2010. In total, 107 411 LT were performed in the US, 357 (0.3%) were for adult polycystic liver disease (PLD). A random group of 9416 adult patients transplanted for other diagnoses was created for comparison (10% of the adult non-PLD database).

Results

Two hundred and seventy-one patients in the adult PLD group were females (75.9%), the mean age was 52.3 ± 8.2 [standard deviation (SD)] years. The median length of transplantation hospital stay was 11 days (interquartile range 8–21). Patients from the PLD group versus the comparison group (9416 patients) consisted of more females, lower Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores (17 versus 21 points), more multi-organ transplants (41% versus 4 %), chronic renal failure (creatinine 2.7 versus 1.5) and fewer patients with chronic hepatitis C (1.4% versus 32%). Peri-operative mortality (≤30 days) was 9% in the PLD versus 6% in the comparison group; however, at 1 year PLD survival was similar (85% versus 85%) to other diagnoses and better at 3 (81% versus 77%) and 5 years (77% versus 71%, overall Log Rank P = 0.006). A similar PLD survival advantage was observed in isolated initial transplants (P = 0.019).

Conclusion

In spite of early technical challenges and mortality, transplantation should be considered an option for selected patients with PLD as excellent long-term outcomes can be achieved.

Introduction

Liver disease affects 5 million people in the United States, of those around 200 000 have polycystic liver disease (PLD). PLD is an autosomal dominant disorder that is frequently associated with polycystic kidney disease (PKD).1–4 PKD is a more aggressive disease that often progresses to end-stage renal disease, dialysis and kidney transplantation.3 PLD is characterized by massive hepatomegaly secondary to numerous diffuse cysts in an otherwise normal functioning liver.5 Patients with PLD usually have normal transaminase, alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin concentrations. Over 70% of patients are women because the epithelial lining of the cysts is sensitive to oestrogen.1,4

Patients become clinically symptomatic when the volume of hepatic cysts increase and patients experience severe abdominal distention and pain, cyst infections, anorexia, dyspnea and a decreased quality of life.2–5 Cysts can also cause portal hypertension, cholangitis, hepatic venous outflow obstruction and inferior vena cava compression.1

The treatment of choice in asymptomatic cases is observation. Mild symptoms are common and should be treated conservatively. Patients who have large, painful cysts, portal hypertension and/or cholangitis are often treated palliatively with cyst decompression done by aspiration or fenestration.1,2,6 A major disadvantage to those options is that the procedure may have to be repeated multiple times owing to recurrence. Hepatic resection is an additional procedure performed to give patients relief of symptoms.2

In some cases orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is needed, especially in advanced cases in which numerous cysts are enlarged, the quality of life of the patient is markedly diminished and other significant complications have occurred such as recurrent cholangitis and portal hypertension.2,6

Great controversy surrounds the option of liver transplantation in PLD patients considering the absence of liver failure, a critical shortage of organs available and substantial risks of surgery. In addition, patients receiving liver transplantation require lifelong monitoring and immunosuppressant medications.1,3,6 Patients with PLD generally have preserved liver function and normal Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores if they do not have renal involvement making transplantation eligibility for these patients difficult. In 2006, Arrazola et al.7 published in Liver Transplantation guidelines for selection of patients with PLD including massive disease (total cyst/parenchyma ratio >1) with complications likely to resolve with liver transplantation, not candidates for or have disease that failed to respond to non-transplant interventions, had clinically significant disease that could be attributed to massive PLD (such as cachexia, ascites, portal hypertension, cholangitis or recurrent cyst infections) and severe malnutrition. They proposed that in the MELD-driven system, eligibility for OLT in PLD patients should continue to be addressed by the Regional Review Board in a case-by-case basis. They further proposed that patients could be given 15 MELD points and MELD could be increased 3 points every 3 months.

The purpose of this study was to determine peri-operative mortality and long-term outcomes in patients undergoing liver transplantation for PLD in the US using the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database.

Methods

The UNOS database was analysed for all patients undergoing transplantation in the United States from 1988 through to 2010. Data from adult patients undergoing OLT with a primary diagnosis of PLD were captured for analysis. A 10% cohort of patients transplanted for a diagnosis other than PLD was randomly selected from the database and used as a comparison group. Data analysed included recipient age, gender, serum creatinine level, total bilirubin level, international normalized ratio, coexisting liver disease, height and weight at the time of transplantation, blood type, length of hospital stay, number of living versus deceased donors, incidence of multi-organ transplantations, and the incidence of acute cellular rejection at 6 months and survival. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared. Donor characteristics, including age, cold ischaemia time and fatty infiltration, were also identified. Paediatric patients were excluded from the analysis.

We compared patient characteristics in the PLD versus the comparison group using rank, chi-square and t-tests as appropriate. Differences in survival between the two groups were analysed with the Kaplan–Meier method using the log-rank test in all transplants and in initial isolated transplants only. Multivariable Cox regression was used to analyse PLD survival versus the comparison group with adjustment for age and gender. Survival in patients undergoing transplantation for PLD with the most common benign indications for transplantation was also compared: alcoholic liver disease, primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). PLD patients were further divided into two groups by whether they were transplanted before the year 2000 or later and compared survival by eras. P = 0.05 was considered significant for all tests. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 10.0.6 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Of 107 411 LT liver transplantation procedures in the database, 357 were performed for adult PLD (0.3%). Three-quarters of PLD patients were female (281/357, 75.9%) and the mean age was 52.3 ± 8.2 [standard deviation (SD)] years. Approximately one-third of PLD LT patients were greater than 55 years old (128/357, 34.6%). Patient characteristics in the PLD versus the comparison group are shown in Table 1. As expected, the group of patients with a diagnosis of PLD consisted of more females, had lower MELD scores (16 versus 20 points), received more multi-organ transplants (42 versus 5 %) and had more chronic renal failure (mean creatinine levels of 2.8 versus 1.4). They had less liver dysfunction (demonstrated by less cholestasis) and a higher INR. The PLD group also had fewer patients with chronic hepatitis C (1.8% versus 28%) than the comparison group.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variable | Adult PLD patients | Other adult liver transplant patients | P-value of difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 357 | 9416 | |

| Males | 86 (24.1%) | 5944 (63.1%) | <0.001 |

| Recipient age years, mean ± SD | 52.3 ± 8.2 | 50.8 ± 10.9 | 0.001 |

| Recipient age >55 years | 128 (35.9%) | 3339 (35.5%) | 0.879 |

| History malignancy | 12 (3.4%) | 766 (8.1%) | 0.001 |

| Unknown or minority race | (24.1%) | (23.9%) | 0.951 |

| Mean BMI kg/m2 ± SD | 26.3 ± 5.1 | 27.4 ± 5.8 | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine at transplant | 2.7 ± 2.5 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | <0.001 |

| INR at transplant | 1.39 ± 1.12 | 1.84 ± 1.36 | <0.001 |

| Cold ischaemic time, mean hours ± SD | 8.6 ± 5.4 | 8.3 ± 4.5 | 0.242 |

| Warm ischaemic time, mean hours ± SD | 44.7 ± 24.1 | 49.2 ± 23.6 | 0.008 |

| MELD score, mean ± SD | 17.2 ± 8.9 | 21.2 ± 10.0 | <0.001 |

| Transplant hospitalization, median days (interquartile range) | 11 (8–21) | 12 (8–25) | 0.070 |

| Time on the waiting list, median days (interquartile range) | 145 (44–434) | 79 (17–243) | <0.001 |

| Recipient on-dialysis week prior to transplant. | 85 (23.8%) | 661 (7.0%) | <0.001 |

| Positive HCV serostatus | 5 (1.4%) | 2998 (31.8%) | <0.001 |

| Positive hepatitis B surface antigen | 2 (0.5%) | 524 (4.9%) | <0.001 |

| Multi-organ transplant | 155 (41.9%) | 512 (4.8%) | <0.001 |

| Recipient on ventilator | 23 (6.2%) | 1057 (9.9%) | 0.019 |

| History portal vein thrombosis | 0 (0%) | 222 (2.1%) | 0.007 |

| Abdominal surgery prior to transplant | 170 (45.9%) | 3691 (34.6%) | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index; INR, International Normalized Ratio; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Survival analysis

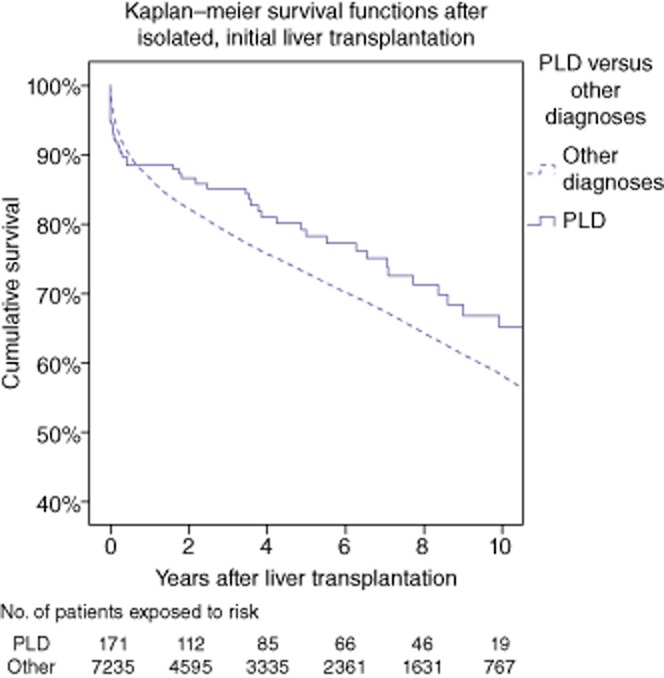

Peri-operative mortality (≤30 days) was higher in the PLD group than the comparison group (9% versus 6%) and survival was lower for the first several months (P < 0.05). However, at 1 year, PLD survival was similar (85% versus 85%) to other diagnoses and was better at 3 (81% versus 77%) and 5 years (77% versus 71%, overall log rank P = 0.006). When excluding patients with multi-organ and repeat transplants, the PLD group (n = 191) had better survival than the comparison group (n = 8098, log rank P = 0.019) with 1-, 3- and 5-year survival of 88%, 85% and 78% versus 87%, 79% and 73%, respectively (Fig. 1). After adjustment for age and gender in a multivariable Cox regression analysis of initial isolated transplant survival, the mortality hazard ratio for PLD patients relative to other transplants remained protective [hazard ratio 0.738, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.550-0.990, P = 0.042]. In comparison with other benign indications, we found that PLD patients had a survival that was better than alcoholic disease patients, similar to PBC and worse than PSC (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Survival in polycystic liver disease (PLD) versus other liver transplant patients undergoing isolated, initial liver transplantation

Figure 2.

Survival in patients undergoing liver transplantation for polycystic liver disease (PLD) compared with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and alcoholic liver disease

Five-year survival improved in PLD patients from 72% in patients transplanted earlier than the year 2000 to 80% in those transplanted in 2000 or later (log rank P = 0.035). In initial isolated transplants between the same periods, the 74% versus the 80% 5-year survival improvement was no longer statistically significant (log rank P = 0.381). Peri-operative mortality was 12% before 2000 versus 7% after year 2000 (P = 0.038, Table 2).

Table 2.

Peri-operative mortality before and after 1 January 2000 in polycystic liver disease (PLD) patients and other transplant diagnoses

| 30-day mortality (1-survival) | <1 January 2000 | ≥1 January 2000 | Wilcoxon's P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLD | 12% (n = 122) | 7% (n = 235) | 0.038 |

| Other transplants | 8% (n = 3520) | 5% (n = 5782) | <0.001 |

Discussion

Polycystic liver disease is often associated with polycystic kidney disease and cystic disease in other organs. Recently, a less frequent form of autosomal dominant of PLD without any associated renal involvement has been described. Most patients with PLD are asymptomatic and do not require operative intervention. In more than 100 000 liver transplant procedures performed during the study period, only 357 were in patients with a diagnosis of PLD representing 0.3% of the total of patients captured in the UNOS dataset. Several authors reported an increased incidence of peri-operative mortality after transplantation suggesting increased complexity of the operative procedure and risk for early complications.1–3 Infectious morbidity was the most common cause of death but a significant number of patients died from intra- or early post-operative bleeding. This treatment option is considered controversial because of the shortage of organs and multiple complications associated with such an extensive surgery for a benign disease. However, some patients are at increased risk of death owing to portal hypertension, recurrent cholangitis and severe malnutrition.

Recently, van Keimpema et al.8 published the largest retrospective analysis using the European Liver Transplantation registry demonstrating excellent long-term survival in patients undergoing transplantation for PLD. They reported a 5-year survival of 87.5% in a series of 58 patients.

Kirchner et al.8 (Hannover, Germany) published the largest single-center experience in 36 patients with PLD. They reported an excellent survival of 86% and confirmed that infectious complications are the most common cause of death in PLD patients after liver transplantation. Cachexia, bleeding from oesophageal varices and recurrent cyst infection were the most common indications for OLT. They reported better survival in these patients undergoing transplantation for PLD than those transplanted for ALD from the European Registry. A very interesting analysis of quality of life was performed in this group of 36 patients transplanted with a diagnosis of PLD and compared with an age-matched group showing a significant improvement in different indicators of quality of life. Cachexia and cyst infection were found to be predictors of increased peri-operative risk. We were able to confirm some of their findings showing that patients undergoing transplantation for PLD have similar survival to those transplanted for alcoholic liver disease and PBC. In our series, patients undergoing isolated liver transplantation have similar outcomes compare to those receiving multi-organ transplants.

Liver transplantation for PLD is technically difficult. The size of the liver, a previous history of invasive procedures prior to transplant and displacement of the vascular and biliary structures in the hilum makes the operation technically challenging. We found that 46% of patients in our series had a history of previous abdominal surgery which was significantly higher than in patients transplanted for other causes. We also demonstrated increased rates of multi-organ transplants in the PLD group as expected. This could be another explanation for increased peri-operative mortality and morbidity which supports increased complexity. Tanner et al. 1 described an increased risk of early post-operative complications but emphasized the increased risk of intra-abdominal bleeding requiring re-exploration. Half of the patients undergoing combined liver and kidney transplantation in this series had post-operative haemorrhage. A direct relationship was also found between death and recipient's age showing that most patients dying in the early post-operative period were 69 years or older. This group also recommended early referral and transplantation as malnutrition is usually associated with poor survival. They also suggested that MELD score exceptions should be considered in this patient population. Like most single-centre experiences from different groups in the US and Europe, that 5-year survival of 80% or greater can be possible in these patients was demonstrated. Furthermore, a significant difference in patient survival in those transplanted with PLD when compared with a random group of more than 10 000 patients transplanted for other diagnoses was shown. It was also demonstrated that patients transplanted with other diagnoses were associated with a 30% increase in mortality risk compared with PLD on multivariate analysis after controlling for age and gender. It is important to mention that these two groups have different characteristics such as creatinine, MELD, number of females, prior surgeries, etc. This makes interpretation of differences in long-term survival difficult. Surprisingly, 30-day mortality analysis demonstrated that patients transplanted with PLD had increased peri-operative mortality even although the group of patients transplanted for other indications had a significantly higher MELD score and were sicker at the time of transplant.

Belghiti et al.3 reported 85% 5-year survival rates in patients undergoing transplantation for PLD. They also showed high morbidity and peri-operative mortality (15%) in their 27 patients transplanted with PLD. These authors favour liver resection with or without fenestration initially and suggested that OLT should be indicated in patients with end-stage renal disease and malnutrition.

Patients transplanted for PLD had a peri-operative mortality of 9.5% higher versus 6.5% found in patients transplanted for other causes different to PLD. This highlights a trend towards increased 30-day mortality in these patients which could support the argument of increased complexity. We also separated the sample in before and after the year 2000 to try to determine differences in peri-operative mortality by era. We found a significant difference in peri-operative mortality by period. Interestingly, 30-day mortality in the PLD group was 7% versus 5% in the comparison group of patients transplanted for diagnosis different than PLD after the year 2000 (Table 2). This represents a significant improvement in peri-operative mortality in recent years for those transplanted for PLD. As expected, more females, renal failure and multi-organ transplants in patients transplanted for PLD but less MELD at transplant and rates of hepatitis C-positive patients were demonstrated.

This is the biggest series of patients transplanted with PLD which included all the US experience during the study period using the UNOS dataset. However, this study has several limitations that should be considered. The utilization of a national database allow data to be collected from a significant number of patients, nevertheless the database was not created to study this specific patient population. For that reason there are important variables that could be of interest that are not captured such us indication of the transplant procedure, pre-transplant treatments, pre-transplant imaging used to determine extension of the disease, operative time, blood product utilization, etc. The strength of this study comes not only from the large number of patients included in the database and the possibility to compare a large number of individuals transplanted with PLD with other patients undergoing transplantation for other indications during the same period of time, but also from its clinically robust and uniform definitions of patient characteristics and events.

In summary, OLT for patients with PLD is associated with higher peri-operative mortality, significantly more abdominal surgeries prior and a higher incidence of multi-organ transplants which could confirm increased complexity. Transplantation should be considered an option for selected patients with PLD as excellent long-term outcomes can be achieved. Unfortunately, we were not able to identify which PLD patients will benefit from OLT. There is a need for future studies to try to determine and establish selection criteria for these patients.

Authorship

R.G., P.G., D.D. designed the research; R.G., P.G. collected data; R.G., D.D., P.G. analysed data; R.G., P.G., M.C., M.D., M.S., J.H. wrote the manuscript; and R.G., P.G., M.C., M.D., M.S., J.H. critically edited the content.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Taner B, Willingham DL, Hewitt WR, Grewal HP, Nguyen JH, Hughes CB. Polycystic liver disease and liver transplantation: single-institution experience. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:3769–3771. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirchner GI, Rifai K, Cantz T, Nashan B, Terkamp C, Becker T, et al. Outcome and quality of life in patients with polycystic liver disease after liver or combined liver-kideny transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1268–1277. doi: 10.1002/lt.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aussilhou B, Douflé G, Hubert C, Francoz C, Paugam C, Paradis V, et al. Extended liver resection for polycystic liver disease can change liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2010;252:735–743. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fb8dc4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gustafsson BI, Friman S, Mjornstedt L, Olausson M, Backman L. Liver transplantation for polycystic liver disease – indications and outcome. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:813–814. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnelldorfer T, Torres VE, Zakaria S, Rosen CB, Nagorney DM. Polycystic liver disease, a critical appraisal of hepatic resection, cyst fenestration and liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2009;250:112–118. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ad83dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pirenne J, Aerts R, Yoong K, Gunson B, Koshiba T, Fourneau I, et al. Liver transplantation for polycystic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:238–245. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.22178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arrazola L, Moonka D, Gish RG, Everson GT. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) exception for polycystic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(12 Suppl. 3):S110–S111. doi: 10.1002/lt.20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Keimpema L, Nevens F, Adam R, Porte RJ, Fikatas P, Becker T, et al. Excellent survival after liver transplantation for isolated polycystic liver disease: an European Liver Transplant Registry study. Transpl Int. 2011;24:1239–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01360.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01360.x. Epub 2011 Sep 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]