Abstract

The concept of “prion-like” has been proposed to explain the pathogenic mechanism of the principal neurodegenerative disorders associated with protein misfolding, including Alzheimer disease (AD). Other evidence relates prion protein with AD: the cellular prion protein (PrPC) binds β amyloid oligomers, allegedly responsible for the neurodegeneration in AD, mediating their toxic effects. We and others have confirmed the high-affinity binding between β amyloid oligomers and PrPC, but we were not able to assess the functional consequences of this interaction using behavioral investigations and in vitro tests. This discrepancy rather than being resolved with the classic explanations, differencies in methodological aspects, has been reinforced by new data from different sources. Here we present data obtained with PrP antibody that not interfere with the neurotoxic activity of β amyloid oligomers. Since the potential role of the PrPC in the neuronal dysfunction induced by β amyloid oligomers is an important issue, find reasonable explanation of the inconsistent results is needed. Even more important however is the relevance of this interaction in the context of the disease, so as to develop valid therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: prion, Alzheimer, oligomers, neurodegeneration, therapy

Introduction

The concept of “prion-like” has been proposed to explain the pathogenic mechanism of all the principal neurodegenerative disorders associated with protein misfolding, including Alzheimer disease (AD). The in vivo demonstration of the seeding mechanism combined with the passage from one cell to another of the pathological proteins in oligomeric form has alimented the prion-like hypothesis.1-4 The concept of transmission is distinguishable from that of infection,5 but it has also been proposed that the pathogenic mechanism of prion diseases and the other neurodegenerative disorders overlap.6,7 The other information relating prion protein to AD is that the toxic effect of β amyloid (Aβ) oligomers may depend on their high affinity binding to cellular prion protein (PrPC).8 The causal role of amyloid deposits in the pathogenesis of AD was formally proposed in the amyloid cascade hypothesis, 20 years ago by Hardy and Higgins (1992),9 this has been recently revisited,10 but the pivotal role of Aβ is substantially confirmed. This has driven therapeutic approaches focused on reducing the presence of Aβ deposits in AD11 brains by various strategies. Unfortunately however clinical trials testing the anti-amyloid treatments, including the recent ones based on the anti-Aβ antibody, showed no significant effects on the progression of AD.12 The timing of the intervention is the main reason for this failure, treatment being given too late to be effective. However it is also possible that the reduction of Aβ deposits, when it occurred, is not sufficient alone to affect the AD.

Aβ Oligomers

Since understanding the pathogenic mechanisms involving Aβ is essential for effective therapies, identificatifying the Aβ species responsible for the neuronal alterations in AD and their actions is a key aspect. The role of soluble small aggregates, known as oligomers, has been consolidated in the last decade as the principal cause of the neurodegeneration in AD. This concept originally arose from the studies in the late nineties, showing that the relation between amyloid fibrils and the neurotoxicity, previously postulated,13 no longer hold. The presence of protofibrils and oligomers as metastable intermediates in the fibrillogenesis14,15 correlates better with the neurotoxicity than the stable fibrils.16,17 Walsh et al. (2002)18 showed that neuronal dysfunction can be acutely produced by exposure of the neurons to naturally secreted Aβ oligomers that inhibit long-term potentiation (LTP), a classic experimental paradigm for synaptic plasticity. The presence at synaptic level of Aβ oligomers was specifically demonstrated19 as well as the abundance of these species in the AD brain.20,21 Furthermore, some mutations of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene, associated with AD, might specifically favor the formation of Aβ oligomers.22,23

Since then, Aβ oligomers have been considered responsible for the neuronal toxicity in AD, and this could explain the absence of any topographic relationship between Aβ deposits and neuronal cell death, as well as the memory decline. Thus, in transgenic mice overexpressing mutated human APP gene, the cognitive behavioral impairment precedes the formation of cortical amyloid plaques.24-27 Although intracellular accumulation of Aβ could also explain these results, it is reasonable to assume that the formation of oligomers precedes the development of amyloid plaques and immediately produces the neurotoxic effect. The neuronal damage induced by soluble aggregates confirms that the best clinical-pathologic correlation in AD is between synaptic loss and cognitive decline.28 The nature and the size of the Aβ oligomer species involved in the neuronal dysfunction and the cellular pathway mediating this effect have been widely debated . The main components of senile plaques are the peptides Aβ 1–40 and Aβ 1–42. Both have self-aggregation capacity but with a clear difference in favor of the longer sequence which in specific conditions in vitro, can spontaneously aggregate within minutes. Other Aβ peptide species present in the brain are Aβ 1–43, and Aβ 1–37 or 1–38, and although a large part of the experimental studies has been conducted using Aβ 1–42 solution, quite possibly a mixture of peptides forms the natural substrate of oligomers. The influence of uncommon peptides is described well in a recent paper where the N-terminally truncated pyroglutamylated form of Aβ, also identified in AD brain, was proposed as the seed of the nucleation of Aβ 1–42 solution.29 As described in the review by Benilova et al. (2012),30 to the native biological variability of Aβ species, we must add the various methodological conditions used to produce these species, or to purify them from brain tissue. Thus, we have Aβ oligomers with biological activity ranging from dimers (8KDa) to large multimeric structures (200–300 KDa). Specific neurotoxic capacity has been attributed to the dodecamer peptide Aβ 56* (56 KDa) based on its appearance in relation with the memory impairment in transgenic mice,31 but in a direct comparison with trimers purified from cell culture Aβ 56* did not show a greater capacity to induce memory impairment when injected ICV in rats.32 In the classical model, the senile plaques are considered to be in dynamic equilibrium with the oligomers; they gradually concentrate in the deposits which in turn act as the reservoir of oligomers that can be released. However the progression from monomeric to oligomeric and successively through protofibrils to fibrils is complex. In some cases oligomers did not generate fibrils (off pathway), in other conditions it has been proposed that oligomers forme fibrils through metastable intermediates33 in a process called “nucleated conformational conversion.” In a standard preparation of Aβ oligomers one occasionally finds species of the same size that are neither toxic nor recognized by oligomer-specific antibodies, indicating that Aβ oligomers can also possess size-independent differences in toxicity.35 Similar size and different toxicity has been shown using β-sheet HypF-N oligomers and non-β-sheet Aβ oligomers. These studies suggest that the toxicity of small amyloidogenic oligomers is governed primarily by the degree of solvent exposure of hydrophobic residues and is weakly influenced by their secondary structures.36,37

Aβ Oligomer Neurotoxicity

Keeping in mind the differences in size, species and biological activity of synthetic or purified Aβ oligomers, there is likely to be similar variability in the biological determinants of the neurotoxic effect. To summarize the numerous data reported, the neurotoxicity of Aβ oligomers can be mediated through three different mechanisms, not mutually exclusive: unspecific perturbation of cellular and intracellular membranes; the formation of amyloid pores, as ion channels and finally, the specific interaction with membrane receptors. The challenge is to understand the pathogenic importance of these processes, not only the reproducibility of each specific event. The effects of various types of oligomer have been studied in vivo and in vitro, and impairment of cognitive function with the direct application of Aβ oligomer solutions has been shown in vivo using natural oligomers from cells38 but also with dimers isolated directly from AD brain.39 Similar results have been obtained with synthetic Aβ oligomers in rats40 and mice41; Aβ oligomers impair long- term potentiation (LTP)18,39,42 and enhance long-term depression (LTD).42 Both these activities involve the NMDA receptors, the receptors are partially blocked by oligomers to induce the inhibition of LTP, while the enhancement of LTD might have different mechanisms, as summarized by Selkoe and Mucke (2012).43

Aβ oligomers might induce internalization or desensitization of NMDA and AMPA receptors, with the loss of dendritic spines. Direct postsynaptic activation of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7-nAChR) by Aβ oligomers was initially proposed,44 and then the activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors,42,45 particularly NR2B-mediated NMDA currents, was shown.46,47 With the NMDA receptor interference induced by Aβ oligomers, it was proposed that numerous intracellular signaling pathways like calcineurin/STEP/cofilin, p38 MAPK, and GSK-3β could be activated.42,45,48-50 Aβ-induced hippocampal neuronal dysfunction occurs through NMDAR-dependent microtubule disassembly with neurite retraction and DNA fragmentation in mature hippocampal cells.51 Together with α7nACh, NMDA and AMPA receptors, several others like insulin receptors,52,53 RAGE (the receptor for advanced glycation end products),54,55 the prion protein,8 the Ephrin-type B2 receptor (EphB2),56,57 and the amylin 3-receptor subtype58 were proposed to specifically mediate the deleterious effect of Aβ oligomers. In various experimental conditions Aβ oligomers can induce tau phosphorylation.29,59-61 This directly links the two major neuropathological hallmarks in AD: the amyloid deposits and the fibrillary tangles made up of hyperphosphorylated tau

The Role of Cellular Prion Protein

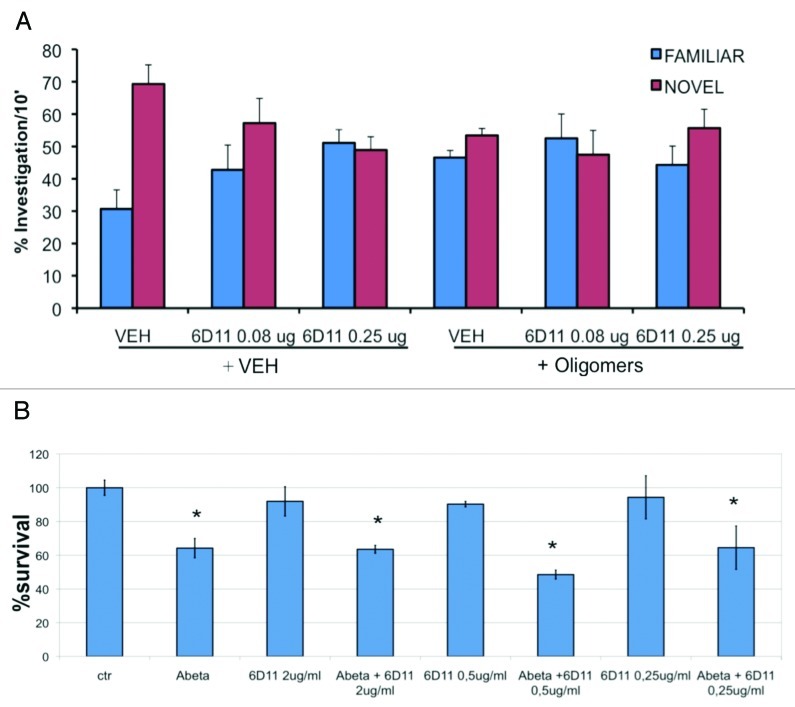

Here we focus on the interaction of Aβ oligomers with PrPC, since we have confirmed only the high-affinity binding between the two41,62,63 but not the functional consequences shown by Strittmatter's group.8 These authors identified PrPc as ligand/receptor of Aβ oligomers, while LTP analysis in vitro and behavioral studies in vivo indicated that in the absence of PrPC Aβ oligomers induced no damage.8,64,65 Using surface plasmon resonance (SPR), the high-affinity binding of Aβ 1–42 oligomers for PrPC was confirmed, whereas a functional role of this association has been excluded by various studies.41,63,66 We approached this issue by directly applying Aβ oligomers in the brain, followed by behavioral examination of memory deficits. The ICV application of Aβ oligomers, 1 µM, induced cognitive impairment assessed by novel object recognition test: the treated mice did not distinguish any more between familiar and novel object. The monomeric solution as well as the Aβ fibers, in the same conditions, did not affect their memory.41 In PrP knockout mice, ICV Aβ oligomers induced the memory deficit similar to that in normally expressing PrPC mice. The ICV application of antibody against Aβ (4G8), ten minutes before Aβ oligomers, completely antagonized the memory impairment.41 In the same condition anti-PrP antibody (6D11) did not affect the behavioral deficit induced by Aβ oligomers, although at a higher dose the antibody had per se a deleterious effect (Fig. 1A). This suggests that Aβ 1–42 oligomers are responsible for cognitive impairment in AD but PrPC is not required for the effect.

Figure 1. Action of anti-PrP antibody (6D11) on the effects of Aβ oligomers. (A) Object recognition test. two concentrations of 6D11 (0.08 and 0.25 µg) were administered 10 min before the ICV injection of vehicle (VEH) or Aβ oligomers (1µM). The effect of Aβ oligomers was similar in the presence or absence of anti-PrP antibody. (B) Viability of murine hippocampal cell cultures exposed for 48 h to Aβ oligomers (1 µM) with vehicle or 6D11 at 0.25, 0.50 and 2 µg/mL. The presence of PrP antibody did not interfere with the Aβ oligomers toxicity. *p < 0.01 vs respective vehicle (Tukey’s test) for methodological details see Balducci et al.41

Similar results were found when the toxicity was tested in vitro. The exposure of cortical neurons to Aβ 1–42 solution at 1 µM reduced cell viability by 30–40% compared with the control condition, in cells expressing PrPC or in cells knockout for PrPC. In this case too, we tested for interference by the anti-PrP antibody, using 6D11, which should recognize the PrP domain involved in the interaction with Aβ 1–42,8 but this antibody did not influence the toxicity of Aβ 1–42 (Fig. 1B). In contrast there was a significant interaction between anti-PrP antibodies (6D11 and 6D13) and the deleterious effect of Aβ oligomers on LTP in murine brain slices or in vivo rats.67 A high concentration of the PrP antibody 6D11 infused for two weeks in double-transgenic mice (APP/PS1) affected cognitive behavior in the radial arm maze test.65 However, the learning curves of the different animal groups were very flat and strongly depended on the performance at the first time point, making it difficult to interpret the results.

The Strittmatter group,68 has shown that the functional consequences of the Aβ 1–42 oligomers-PrPC interaction are mediated downstream by the activation of Fyn signaling. The timing (a large part of the effects are studied with exposure of only minutes) and the quantitative effect associated with the Aβo/PrPC/Fyn mechanism, in terms of synaptic dysfunction, interaction with NMDA receptors, and toxicity leave doubts about the relevance of this phenomenon. Furthermore, as the authors mention, a physical interaction of PrPC with Fyn is unlikely since PrPC is attached extracellularly to the membrane with a GPI anchor, while Fyn is inside the cell. In vivo experiments showed that the epileptic status of the APPSwe/PSenDE9 mice was strongly attenuated when PrPC was nullified. This may indicate an interaction between the expressed transgene and PrPC, but the epileptic discharge is closely related to these specific transgenic mice. Other APP single, double and triple transgenic mice, like most AD patients, do not show this condition.

A different mechanism of interaction between PrPC and Aβ oligomers was proposed by You et al. (2012).69 They showed that PrPC can be a key regulator of NMDAR activity. They hypothesized that PrPC, in its copper-loaded state, binds to the NMDAR complex to allosterically reduce its glycine affinity, thereby increasing desensitization. When copper is chelated or when PrPC is absent or functionally compromised (by GPI anchor cleavage or binding to Aβ oligomers, for example), glycine affinity is enhanced, reducing receptor desensitization and producing pathologically large, steady-state currents that contribute to neuronal damage. Other studies have shown a role of PrPC in the Aβ 1–42 oligomers neurotoxicity,70,71 while the influence of PrPC was excluded in an in vivo investigation of cognitive behavior in J20 mice,72 confirming the differences. As mentioned above, this scientific dispute should proceed to the physopathological meanings that have still to be established.

We have described here the complexity of Aβ oligomer formation and the multiple possibilities of their interaction with the cellular membranes and proteins. This issue has been addressed in specific studies73,74 and discussed in a previous review.75 The results indicate that PrPC is only one of the numerous entities potentially interacting with Aβ oligomers and may have an essential role in their toxicity only in specific conditions.

Conclusions

As recently pointed out by Westaway and Jhamandas (2012)76 taking in account of the potential negative synergistic effect of Aβ oligomers-PrPC, there is also ample data in favor of a neuroprotective effect of PrPC.77-80 Rial et al. (2012)81 showed that the overepression of PrPC in transgenic mice prevented cognitive dysfunction and the apoptotic neuronal cell death induced by Aβ1–40. In terms of the relevance of the findings, the neuroprotective activity of PrPC in various experimental conditions must be evaluated together with the enormous differences in the epidemiology of the diseases that seem to exclude the direct links between AD and prion-related encephalopathies as the essential role of PrPC proposed in both conditions might indicate. However, independently from the real functional consequence of the Aβ oligomers-PrPC interaction, the high affinity of this binding has been widely confirmed. Nieznaski et al. (2012)82 tested the capacity of recombinant PrP 23–231 to interfere with the Aβ1–42 fibrillogenesis. At low concentrations (0.1–1µM) and low molar ratio (1/20 to 1/100) the prion protein co-incubated with Aβ1–42 inhibited the formation of oligomers and fibrils and prevented the toxicity of Aβ1–42 in cell cultures. As the authors point out, two domains (95–110 and N-terminal basic residues) of PrP are required for the anti-amyloidogenic effect and both are included in the N-terminal N1 fragment (residues 23–110/111) released from the membrane-anchored PrPC.83 The N1 fragment had neuroprotective activity in vivo in rat retina ischemia model,84 and also in primary cultured neurons exposed to Aβ oligomers.85 Thus, although the physiopathological consequences of the Aβ1–42-PrPC interaction remain to be clarified we can reach a common point of view on the possible therapeutic prospects.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/prion/article/23286

References

- 1.Meyer-Luehmann M, Coomaraswamy J, Bolmont T, Kaeser S, Schaefer C, Kilger E, et al. Exogenous induction of cerebral beta-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host. Science. 2006;313:1781–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1131864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisele YS, Obermüller U, Heilbronner G, Baumann F, Kaeser SA, Wolburg H, et al. Peripherally applied Abeta-containing inoculates induce cerebral beta-amyloidosis. Science. 2010;330:980–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1194516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brundin P, Melki R, Kopito R. Prion-like transmission of protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:301–7. doi: 10.1038/nrm2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanouchi T, Ohkubo T, Yokota T. Can regional spreading of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis motor symptoms be explained by prion-like propagation? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:739–45. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguzzi A, Rajendran L. The transcellular spread of cytosolic amyloids, prions, and prionoids. Neuron. 2009;64:783–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prusiner SB. Cell biology. A unifying role for prions in neurodegenerative diseases. Science. 2012;336:1511–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1222951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soto C. Transmissible proteins: expanding the prion heresy. Cell. 2012;149:968–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurén J, Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Gilbert JW, Strittmatter SM. Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-beta oligomers. Nature. 2009;457:1128–32. doi: 10.1038/nature07761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: a critical reappraisal. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1129–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selkoe DJ, Schenk D. Alzheimer’s disease: molecular understanding predicts amyloid-based therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:545–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.140248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callaway E. Alzheimer’s drugs take a new tack. Nature. 2012;489:13–4. doi: 10.1038/489013a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pike CJ, Walencewicz AJ, Glabe CG, Cotman CW. Aggregation-related toxicity of synthetic beta-amyloid protein in hippocampal cultures. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;207:367–8. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(91)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harper JD, Wong SS, Lieber CM, Lansbury PT. Observation of metastable Abeta amyloid protofibrils by atomic force microscopy. Chem Biol. 1997;4:119–25. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(97)90255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh DM, Lomakin A, Benedek GB, Condron MM, Teplow DB. Amyloid beta-protein fibrillogenesis. Detection of a protofibrillar intermediate. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22364–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forloni G, Lucca E, Angeretti N, Della Torre P, Salmona M. Amidation of beta-amyloid peptide strongly reduced the amyloidogenic activity without alteration of the neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 1997;69:2048–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69052048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, et al. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6448–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–9. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Chang L, Fernandez SJ, Gong Y, Viola KL, et al. Synaptic targeting by Alzheimer’s-related amyloid beta oligomers. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10191–200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong Y, Chang L, Viola KL, Lacor PN, Lambert MP, Finch CE, et al. Alzheimer’s disease-affected brain: presence of oligomeric A beta ligands (ADDLs) suggests a molecular basis for reversible memory loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10417–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834302100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barghorn S, Nimmrich V, Striebinger A, Krantz C, Keller P, Janson B, et al. Globular amyloid beta-peptide oligomer - a homogenous and stable neuropathological protein in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2005;95:834–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilsberth C, Westlind-Danielsson A, Eckman CB, Condron MM, Axelman K, Forsell C, et al. The ‘Arctic’ APP mutation (E693G) causes Alzheimer’s disease by enhanced Abeta protofibril formation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:887–93. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomiyama T, Nagata T, Shimada H, Teraoka R, Fukushima A, Kanemitsu H, et al. A new amyloid beta variant favoring oligomerization in Alzheimer’s-type dementia. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:377–87. doi: 10.1002/ana.21321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsia AY, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Yu GQ, Tatsuno G, Hu K, et al. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3228–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holcomb LA, Gordon MN, Jantzen P, Hsiao K, Duff K, Morgan D. Behavioral changes in transgenic mice expressing both amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 mutations: lack of association with amyloid deposits. Behav Genet. 1999;29:177–85. doi: 10.1023/A:1021691918517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Dam D, D’Hooge R, Staufenbiel M, Van Ginneken C, Van Meir F, De Deyn PP. Age-dependent cognitive decline in the APP23 model precedes amyloid deposition. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:388–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balducci C, Tonini R, Zianni E, Nazzaro C, Fiordaliso F, Salio M, et al. Cognitive deficits associated with alteration of synaptic metaplasticity precede plaque deposition in AßPP23 transgenic mice. J. Alzh Dis. 2010;21:1367–81. doi: 10.3233/jad-2010-100675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeKosky ST, Scheff SW. Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer’s disease: correlation with cognitive severity. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:457–64. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nussbaum JM, Schilling S, Cynis H, Silva A, Swanson E, Wangsanut T, et al. Prion-like behaviour and tau-dependent cytotoxicity of pyroglutamylated amyloid-β. Nature. 2012;485:651–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benilova I, Karran E, De Strooper B. The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:349–57. doi: 10.1038/nn.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee J, Culyba EK, Powers ET, Kelly JW. Amyloid-β forms fibrils by nucleated conformational conversion of oligomers. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:602–9. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lesné S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, et al. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reed MN, Hofmeister JJ, Jungbauer L, Welzel AT, Yu C, Sherman MA, et al. Cognitive effects of cell-derived and synthetically derived Aβ oligomers. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:1784–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chromy BA, Nowak RJ, Lambert MP, Viola KL, Chang L, Velasco PT, et al. Self-assembly of Abeta(1-42) into globular neurotoxins. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12749–60. doi: 10.1021/bi030029q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ladiwala AR, Litt J, Kane RS, Aucoin DS, Smith SO, Ranjan S, et al. Conformational differences between two amyloid β oligomers of similar size and dissimilar toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:24765–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.329763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zampagni M, Cascella R, Casamenti F, Grossi C, Evangelisti E, Wright D, et al. A comparison of the biochemical modifications caused by toxic and non-toxic protein oligomers in cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:2106–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stravalaci M, Bastone A, Beeg M, Cagnotto A, Colombo L, Di Fede G, et al. Specific recognition of biologically active amyloid-β oligomers by a new surface plasmon resonance-based immunoassay and an in vivo assay in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:27796–805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.334979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, Shankar GM, Kuskowski MA, Selkoe DJ, et al. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-beta protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837–42. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scopes DI, O’Hare E, Jeggo R, Whyment AD, Spanswick D, Kim EM, et al. Aβ oligomer toxicity inhibitor protects memory in models of synaptic toxicity. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:383–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balducci C, Beeg M, Stravalaci M, Bastone A, Sclip A, Biasini E, et al. Synthetic amyloid-beta oligomers impair long-term memory independently of cellular prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2295–300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911829107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li S, Hong S, Shepardson NE, Walsh DM, Shankar GM, Selkoe D. Soluble oligomers of amyloid Beta protein facilitate hippocampal long-term depression by disrupting neuronal glutamate uptake. Neuron. 2009;62:788–801. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mucke L, Selkoe DJ. Neurotoxicity of Amyloid β-Protein: Synaptic and Network Dysfunction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006338. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG, Paul S, Moran T, Choi EY, et al. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-beta. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1051–8. doi: 10.1038/nn1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shankar GM, Bloodgood BL, Townsend M, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ, Sabatini BL. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2866–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferreira IL, Bajouco LM, Mota SI, Auberson YP, Oliveira CR, Rego AC. Amyloid beta peptide 1-42 disturbs intracellular calcium homeostasis through activation of GluN2B-containing N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in cortical cultures. Cell Calcium. 2012;51:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li S, Jin M, Koeglsperger T, Shepardson NE, Shankar GM, Selkoe DJ. Soluble Aβ oligomers inhibit long-term potentiation through a mechanism involving excessive activation of extrasynaptic NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6627–38. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0203-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Q, Walsh DM, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ, Anwyl R. Block of long-term potentiation by naturally secreted and synthetic amyloid beta-peptide in hippocampal slices is mediated via activation of the kinases c-Jun N-terminal kinase, cyclin-dependent kinase 5, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase as well as metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3370–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1633-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tackenberg C, Brandt R. Divergent pathways mediate spine alterations and cell death induced by amyloid-beta, wild-type tau, and R406W tau. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14439–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3590-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sclip A, Antoniou X, Colombo A, Camici GG, Pozzi L, Cardinetti D, et al. c-Jun N-terminal kinase regulates soluble Aβ oligomers and cognitive impairment in AD mouse model. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:43871–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.297515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mota SI, Ferreira IL, Pereira C, Oliveira CR, Rego AC. Amyloid-beta peptide 1-42 causes microtubule deregulation through N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in mature hippocampal cultures. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:844–56. doi: 10.2174/156720512802455322. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Felice FG, Vieira MN, Bomfim TR, Decker H, Velasco PT, Lambert MP, et al. Protection of synapses against Alzheimer’s-linked toxins: insulin signaling prevents the pathogenic binding of Abeta oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1971–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809158106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bomfim TR, Forny-Germano L, Sathler LB, Brito-Moreira J, Houzel JC, Decker H, et al. An anti-diabetes agent protects the mouse brain from defective insulin signaling caused by Alzheimer’s disease- associated Aβ oligomers. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1339–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI57256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan SD, Chen X, Fu J, Chen M, Zhu H, Roher A, et al. RAGE and amyloid-beta peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1996;382:685–91. doi: 10.1038/382685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kook SY, Hong HS, Moon M, Ha CM, Chang S, Mook-Jung IA. Aβ₁₋₄₂-RAGE interaction disrupts tight junctions of the blood-brain barrier via Ca²⁺-calcineurin signaling. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8845–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6102-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Furlow PW, Clemente AS, Velasco PT, Wood M, et al. Abeta oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27:796–807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3501-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cissé M, Halabisky B, Harris J, Devidze N, Dubal DB, Sun B, et al. Reversing EphB2 depletion rescues cognitive functions in Alzheimer model. Nature. 2011;469:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature09635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fu W, Ruangkittisakul A, MacTavish D, Shi JY, Ballanyi K, Jhamandas JH. Amyloid β (Aβ) peptide directly activates amylin-3 receptor subtype by triggering multiple intracellular signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18820–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.331181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Felice FG, Wu D, Lambert MP, Fernandez SJ, Velasco PT, Lacor PN, et al. Alzheimer’s disease-type neuronal tau hyperphosphorylation induced by A beta oligomers. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:1334–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jin M, Shepardson N, Yang T, Chen G, Walsh D, Selkoe DJ. Soluble amyloid beta-protein dimers isolated from Alzheimer cortex directly induce Tau hyperphosphorylation and neuritic degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5819–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017033108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma QL, Yang F, Rosario ER, Ubeda OJ, Beech W, Gant DJ, et al. Beta-amyloid oligomers induce phosphorylation of tau and inactivation of insulin receptor substrate via c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling: suppression by omega-3 fatty acids and curcumin. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9078–89. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1071-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen S, Yadav SP, Surewicz WK. Interaction between human prion protein and amyloid-beta (Abeta) oligomers: role OF N-terminal residues. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26377–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Calella AM, Farinelli M, Nuvolone M, Mirante O, Moos R, Falsig J, et al. Prion protein and Abeta-related synaptic toxicity impairment. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:306–14. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Coffey EE, Gunther EC, Laurén J, Gimbel ZA, et al. Memory impairment in transgenic Alzheimer mice requires cellular prion protein. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6367–74. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0395-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chung E, Ji Y, Sun Y, Kascsak RJ, Kascsak RB, Mehta PD, et al. Anti-PrPC monoclonal antibody infusion as a novel treatment for cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease model mouse. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kessels HW, Nguyen LN, Nabavi S, Malinow R. The prion protein as a receptor for amyloid-beta. Nature. 2010;466:E3–4, discussion E4-5. doi: 10.1038/nature09217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barry AE, Klyubin I, Mc Donald JM, Mably AJ, Farrell MA, Scott M, et al. Alzheimer’s disease brain-derived amyloid-β-mediated inhibition of LTP in vivo is prevented by immunotargeting cellular prion protein. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7259–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6500-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Um JW, Nygaard HB, Heiss JK, Kostylev MA, Stagi M, Vortmeyer A, et al. Alzheimer amyloid-β oligomer bound to postsynaptic prion protein activates Fyn to impair neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1227–35. doi: 10.1038/nn.3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.You H, Tsutsui S, Hameed S, Kannanayakal TJ, Chen L, Xia P, et al. Aβ neurotoxicity depends on interactions between copper ions, prion protein, and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1737–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110789109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Freir DB, Nicoll AJ, Klyubin I, Panico S, Mc Donald JM, Risse E, et al. Interaction between prion protein and toxic Aß assemblies can be therapeutically targeted at multiple sites. Nature Commun. 2011;2:336. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bate C, Williams A. Amyloid-β-induced synapse damage is mediated via cross-linkage of cellular prion proteins. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:37955–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.248724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cissé M, Sanchez PE, Kim DH, Ho K, Yu GQ, Mucke L. Ablation of cellular prion protein does not ameliorate abnormal neural network activity or cognitive dysfunction in the J20 line of human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10427–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1459-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Virok DP, Simon D, Bozsó Z, Rajkó R, Datki Z, Bálint É, et al. Protein array based interactome analysis of amyloid-β indicates an inhibition of protein translation. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:1538–47. doi: 10.1021/pr1009096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Manzoni C, Colombo L, Bigini P, Diana V, Cagnotto A, Messa M, et al. The molecular assembly of amyloid aβ controls its neurotoxicity and binding to cellular proteins. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Forloni G, Balducci C. β-amyloid oligomers and prion protein: Fatal attraction? Prion. 2011;5:10–5. doi: 10.4161/pri.5.1.14367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Westaway D, Jhamandas JH. The P’s and Q’s of cellular PrP-Aβ interactions. Prion. 2012;6:359–63. doi: 10.4161/pri.20675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zanata SM, Lopes MH, Mercadante AF, Hajj GN, Chiarini LB, Nomizo R, et al. Stress-inducible protein 1 is a cell surface ligand for cellular prion that triggers neuroprotection. EMBO J. 2002;21:3307–16. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martins VR, Beraldo FH, Hajj GN, Lopes MH, Lee KS, Prado MM, et al. Prion protein: orchestrating neurotrophic activities. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2010;12:63–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Linden R, Martins VR, Prado MA, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, Brentani RR. Physiology of the prion protein. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:673–728. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Turnbaugh JA, Westergard L, Unterberger U, Biasini E, Harris DA. The N-terminal, polybasic region is critical for prion protein neuroprotective activity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rial D, Piermartiri TC, Duarte FS, Tasca CI, Walz R, Prediger RD. Overexpression of cellular prion protein (PrP(C)) prevents cognitive dysfunction and apoptotic neuronal cell death induced by amyloid-β (Aβ₁₋₄₀) administration in mice. Neuroscience. 2012;215:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nieznanski K, Choi JK, Chen S, Surewicz K, Surewicz WK. Soluble prion protein inhibits amyloid-β (Aβ) fibrillization and toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33104–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C112.400614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vincent B, Paitel E, Saftig P, Frobert Y, Hartmann D, De Strooper B, et al. The disintegrins ADAM10 and TACE contribute to the constitutive and phorbol ester-regulated normal cleavage of the cellular prion protein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37743–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Guillot-Sestier MV, Sunyach C, Druon C, Scarzello S, Checler F. The α-secretase-derived N-terminal product of cellular prion, N1, displays neuroprotective function in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35973–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.051086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guillot-Sestier MV, Sunyach C, Ferreira ST, Marzolo MP, Bauer C, Thevenet A, et al. α-Secretase-derived fragment of cellular prion, N1, protects against monomeric and oligomeric amyloid β (Aβ)-associated cell death. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:5021–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.323626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]