Abstract

Fibrillar aggregates of misfolded amyloid proteins are involved in a variety of diseases such as Alzheimer disease (AD), type 2 diabetes, Parkinson, Huntington and prion-related diseases. In the case of AD amyloid β (Aβ) peptides, the toxicity of amyloid oligomers and larger fibrillar aggregates is related to perturbing the biological function of the adjacent cellular membrane. We used atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of Aβ9–40 fibrillar oligomers modeled as protofilament segments, including lipid bilayers and explicit water molecules, to probe the first steps in the mechanism of Aβ-membrane interactions. Our study identified the electrostatic interaction between charged peptide residues and the lipid headgroups as the principal driving force that can modulate the further penetration of the C-termini of amyloid fibrils or fibrillar oligomers into the hydrophobic region of lipid membranes. These findings advance our understanding of the detailed molecular mechanisms and the effects related to Aβ-membrane interactions, and suggest a polymorphic structural character of amyloid ion channels embedded in lipid bilayers. While inter-peptide hydrogen bonds leading to the formation of β-strands may still play a stabilizing role in amyloid channel structures, these may also present a significant helical content in peptide regions (e.g., termini) that are subject to direct interactions with lipids rather than with neighboring Aβ peptides.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, Aβ fibrillar oligomers, Aβ peptide fibrils, Aβ protofilaments, amyloid channels, structural polymorphism of amyloid aggregates

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is characterized by a strong loss of cognitive functions that is pathologically correlated with the appearance in neural tissue of fibrillar deposits in extracellular plaques and intracellular tangles containing amyloid β (Aβ) peptides and tau proteins, respectively. Two mutually non-exclusive concepts emerged regarding Aβ neurotoxicity, one is that the peptides may be cytotoxic by themselves1,2 and that their aggregation is required for toxicity,3,4 and the other is that the amyloid peptides may interfere synergistically with the normal biochemical processes involving other molecules.5,6

It has been demonstrated that amyloid plaques can be induced in mice via intra-cerebral7 or intra-peritoneal8 injection of misfolded Aβ-containing brain extract, this behavior of the peptide being similar to that of prions.9 However, there is no direct evidence that injected Aβ is both necessary and sufficient to trigger cerebral amyloid deposition without cofactors that facilitate its aggregation. Induction of amyloid formation in vivo with synthetic Aβ has been unsuccessful so far, leading to the hypothesis that an amyloid-enhancing factor or a particular peptide conformation is required to trigger its deposition in vivo.7

Several studies have supported the idea that the interactions between Aβ peptides and cellular membranes lead to the formation of fibrillar Aβ aggregates and to their subsequent cytotoxicity.10,11 The presence of intermediate aggregation products (Aβ oligomers) in the extracellular or intracellular environment, rather than that of fully formed fibrils, seems to alter the membrane structure and functions and is related to the dysregulation of cellular ionic homeostasis.12

Although the details of the molecular mechanism of membrane permeation are unknown, amyloid oligomers have been shown to interact with lipid membranes and cause nonspecific ion leakage,13-15 or may transform into annular protofibrils that can form ion channel-like structures.16-18

Finding detailed molecular information about the structural organization of amyloid fibrils, fibrillar and pre-fibrilar oligomers and annular amyloid channels remains a major yet challenging goal of both experimental and computational modeling studies of Aβ aggregates. In a recent study,19 we used molecular modeling in conjunction with atomistic molecular dynamics to investigate in detail the early steps in the mechanisms of interaction between preformed Aβ9–40 fibrillar oligomers (generated using protofilament-like structures20,21) and a model bilayer membrane consisting of 98 POPE lipids. The initial protofilament structures are built based on experimental and computational studies of Aβ protofilaments formed in solution,20,22 which have been simulated and studied previously in detail both under physiological conditions20 and at elevated temperatures.21 Consistent with previous studies, the first eight residues from the N-terminus of the Aβ peptides are not included in the protofilament models because they were shown to be significantly more disordered than residues in the 9–40 region.19-21,23-25 The main focus of our new work19 is on the atomistically detailed analysis of the role of different molecular and structural elements in the stability and conformational dynamics of Aβ protofilaments near lipid bilayers, and on the implications on the mechanism of possible insertion of fibrillar oligomers and protofilaments into the membrane.

Molecular Interactions with POPE Lipids

In reference 19, we used MD simulations to probe with atomistic-level detail the mechanism of interaction between molecular models of protofilaments of Aβ40 peptides and a POPE lipid bilayer in explicit water. The POPE lipids were chosen similarly to previous studies,26,27 and because the smaller headgroups of POPE lipids are expected to promote a more favorable interaction with amyloid peptides. Note however, that we have later used POPC lipids as well (see below) which lead to generally less favorable interactions with inserted peptides, being thus more stringent tests of the stability of amyloid channels. Here, we built protofilament systems consisting of eight Aβ peptides and explicit water molecules, with a total number of 42 to 57 thousand atoms, with different initial conformations, and simulated them for 150 ns each in the NPT ensemble (i.e., constant number of molecules, pressure and temperature), using periodic boundary conditions, at a constant pressure of 1 atm and at the temperature of 310 K, close to the physiological values, similar to previous studies.19-21,28 The simulation range was long enough to observe the first detailed steps of the intermolecular interactions. After the Aβ protofilaments lost their initially ordered β-sheet-rich structures, they reached quasi-equilibrated states, preserving only a fraction of their characteristic β-sheet content. The change of structure near the membrane was significantly greater than the change observed for corresponding simulations in bulk water,20,21 due to the presence of the specific lipid environment.

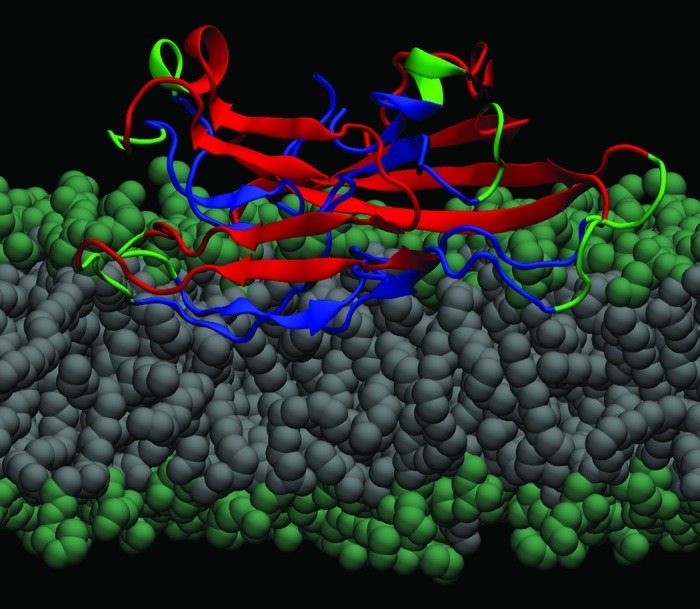

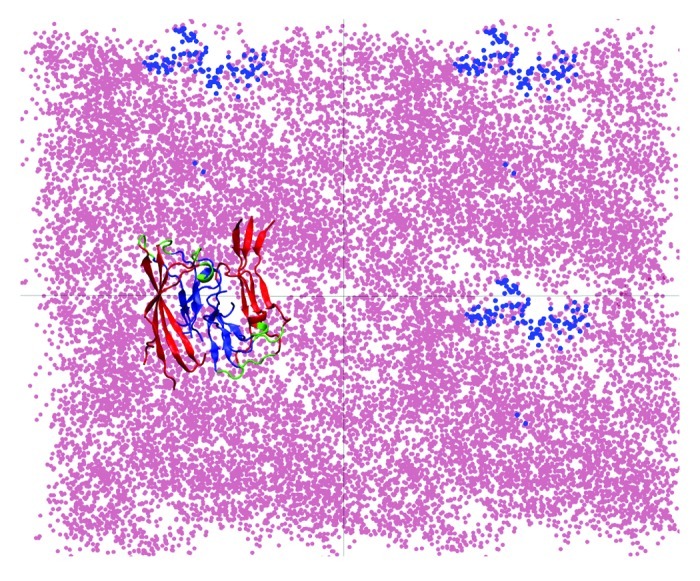

Analysis of both the change in the number of peptide-related hydrogen bonds (NHBs) and of the electrostatic interactions between the peptides in the protofilament and the membrane demonstrated that the changes observed in structure of the protofilaments are due to specific interactions with the lipids.19 We identified the electrostatic attraction between the charged residues and the lipid headgroups acting as the main driving force that leads to a further penetration of the C-termini into the hydrophobic lipid tails region, as illustrated in Figure 1. At the same time, we observed perturbations in the membrane as an effect of the proximity of the protofilaments, as the lipid headgroups reposition themselves around the charged residues, as shown in Figure 2. This figure shows that, along the MD trajectory there is an area consistently avoided by the center of mass (COM) of the phosphorus atoms, which coincides with the COM positions of the atoms in the C-termini. Also, the tails in the upper membrane leaflet reorient themselves closer to the surface and the C-termini, which leads to a local membrane-thinning effect.19 Our study demonstrates that in the proximity of lipid membranes the protofilaments adopt structures that have a lower content of β-sheet compared with the ones formed in bulk water. Although the timescales accessible to MD studies cannot provide us with a full insight into the complete insertion process of aggregated Aβ peptide structures into the membrane, the early interactions observed show that the structure formed in solution cannot be transferred to the membrane environment without a significant loss of β-sheet content. This concept has direct potential implications in the understanding and further modeling of Aβ ion channel-like structures formed in membranes.

Figure 1. Molecular model of an Aβ40 fibrillar octamer interacting with a POPE bilayer membrane (lateral view). The N-terminal β-strands are shown in red, the core C-terminal β-strands are blue, and the turn regions are green. The hydrophilic lipid headgroups (lime) and the lipid tails (gray) are illustrated by spheres.

Figure 2. Repositioning of lipid headgroups due to interactions with the Aβ40 protofilament segment facilitates the access of the hydrophobic C-terminal β-strands into the lipid tail region (top view; see also Fig. 1). Here, four top-view periodic images of the simulation box are shown for a typical trajectory. The dots represent the positions sampled by the center of mass (COM) of the lipid P atoms (pink) and the COM of the C-termini (blue) during the 45 to 150 ns trajectory segment when the C-termini are associated with the lipid head groups. A representative Aβ9–40 octamer structure is shown in only one periodic image.

In our MD studies, after the initial protofilament association with the lipid bilayer (i.e., at about 45 ns of NPT dynamics), the content of β-sheet structure was stable for the rest of the simulation and we observed little helical structure formation. These results suggest that, if the channels are formed through direct membrane incorporation of β-sheet-rich fibrillar oligomers, these would need to undergo further conformational changes before or after being incorporated into lipid bilayers, and may need to be associated with other similar units in order to form β-turn-β ion channel-like structures.

Note also that experimental studies showed that it is the prefibrillar, globular-like oligomers rather than the fibrillar ones that might associate into annular structures,28 but their exact secondary structure is still unkown. Another possibility is that the predominantly helical membranar Aβ peptides may be associated with other similarly-structured Aβ monomers before leaving the membrane, as there have been studies29 supporting the idea of dimerization in the transmembranar domain of APP. On the other hand, experimental studies analyzing the structure of Aβ peptides in membranes, amyloid channels or pore-like structures showed that they contained a high percentage of β-sheet,30-32 suggesting that, if it the aggregation starts from a helical structure, the N-terminus may adopt β-sheet conformations, while the C-terminus has been shown to have a high percentage of helix when in a lipid environment.33

Polymorphism of Aβ Peptide Channels

The ability of amyloid oligomers to perturb cellular membranes, whether it is by thinning the membrane or through ion channel formation, is related to their cytotoxicity. Our study of Aβ40 interacting with a POPE bilayer focused on the mechanism of interaction between fibrillar oligomers and lipid bilayer models. Understanding these interactions opens new questions on the molecular pathways of aggregation of Aβ peptides into annular channel-like membrane structures. Membrane disruption by non-fibrillar (globular) amyloid proteins is followed by an increase in membrane conductance either through specific18 or non-specific ion leakage.13 The mechanism of globular oligomers inducing cell dysfunction due to membrane permeabilization has been documented in several studies,14,34 but their atomistic structure in membrane is still unknown. Experimental evidence (e.g., X-ray fiber diffraction and solid-state NMR) has characterized the Aβ fibrilar aggregates in solution as being definitely β-sheet rich, whereas their conformations in lipid bilayers is largely unclear. Previous studies predicted Aβ ion channel conformations based on the peptide sequence and on how it relates to other patterns observed in different membrane-bound and channel-forming peptides and proteins.35 More recently, electron microscopy images revealed “pore-like” annular structures for amyloidogenic protofibrils (i.e., mutants of Aβ1–40 and of α-synuclein).17 However, these structures were not formed in membranes and were not associated within bilayers, their atomistic details in lipids being uncertain. Using a series of experimental techniques (AFM, CD, gel electrophoresis and electrophysiological recordings), reference 36 showed that amyloid proteins including Aβ40, α-synuclein and amylin can undergo structural conformation changes and associate into ion-channel-like structures comprising typically of a few subunits. It has also been suggested that an α-helical form can be involved in a process of membrane poration.37,38

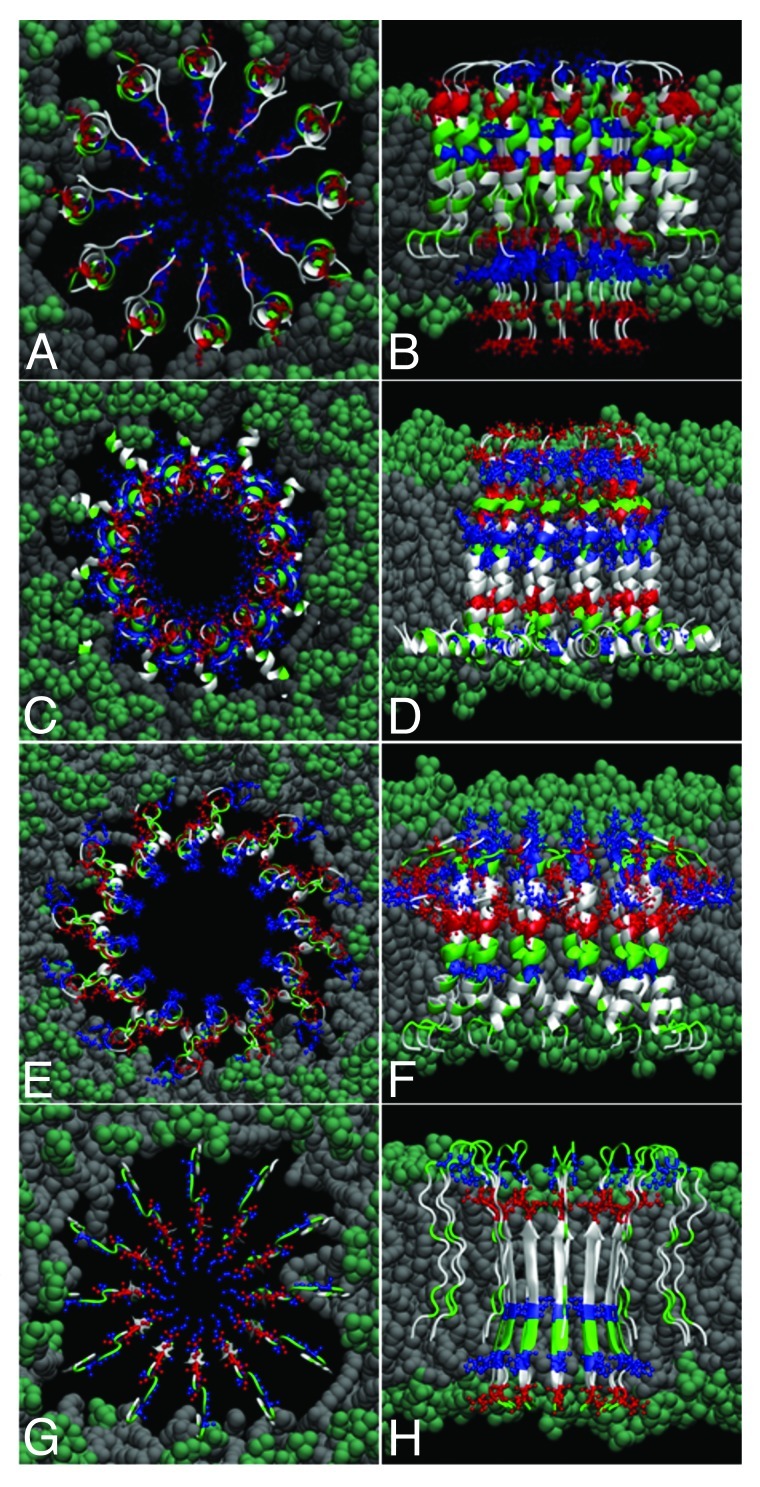

Based on similar experimental studies39-42 Nussinov et al. pioneered the atomistic modeling of these structures.43-47 These models comprise of 10 to 24 Aβ40 or Aβ42 monomers, each with a β-turn-β structure - the main tertiary structure motif that characterizes the peptide as part of mature fibrils in formed in water. MD refinement of these models shows that the initially continuous fibrillar structures break in about the same number of oligomeric subunits as reported by AFM imaging experiments, the final channel-like structure having similar dimensions compared with the AFM images. The Aβ N-termini maintain essentially their initial β-sheet structures, whereas the C-termini become more distorted. These studies, together with others looking at structures that aggregated Aβ peptides can adopt in lipids or different hydrophobic environments (e.g., some that consist of two helical regions of residues 8 to 25, and 28 to 38,33,48-51) led us to infer that the β-turn-β might not be necessarily the only structural motif adopted by Aβ peptides when embedded in lipid bilayers. Some of our recent models shown in Figure 3 consist of 12 monomers with a combined β-strand in the N-termini region and helical C-termini. Here, 12-mer channels are shown for illustrative purposes, and to keep the size of the overall atomistic model small. However, similar atomistic models may be easily extended to larger (e.g., 16-mer, 20-mer, etc.) amyloid-channel-like structures. Here, we have also modeled two structures containing only α-helices and no significant β-strand content. We note that, while these all-atom models were built using a standard force fields and have been minimized and equilibrated using explicit water molecules (i.e., similarly to the methods described in Ref.19) they have not been yet fully tested and are only suggestions of such possible structures.

Figure 3. Possible models of Aβ dodecameric ion channels. The 12 peptides are colored by residue type: blue, positively charged; red, negative; green, polar; white, nonpolar. Top (A,C,E,G) and lateral (B,D,F,H) views of several models (see text).

For example, to obtain the first model (shown in Fig. 3A and 3B), we merged structures of an Aβ monomer in a two-stranded fibril of Tycko’s model22 (which has thus originally a β-turn-β pattern) with the helical structure of Aβ40 suggested in Ref.52 The result, represented in Figure 3A, is a transmembrane-spanning channel-like structure with the N-termini containing charged residues (D1, E3, R5, H6, D7, E11, H13, H14 and K16) in the interior, as β-strands, and the more hydrophobic C-termini modeled as helices toward the exterior of the channel, interacting with the hydrophobic lipid tails. Note that the charged residues are structurally located such that the first two negatively-charged residues (D1, E3) would interact with the positively-charged amino groups of the lipid headgroups and thus stabilize (anchor) the protein segments in the lower membrane leaflet. The same kind of rationalization goes for the top part of the channel, with the charged residues E22 and D23 performing the same role. Here, we used POPC lipids, which are found abundantly in the membrane of neuronal cells, have the same tails as POPE,19 but the ethanolamine is replaced by choline in their headgroups. Our lipid bilayer has a thickness of about 38 Ǻ (i.e., between the planes containing phosphorus atoms in the two membrane leaflets).

In Figure 3C, E and G (top views) and 3b, 3d, 3f (lateral views) are shown other possible structural models of transmembrane amyloid channels. In Figure 3C and D is shown an Aβ1–42 channel modeled as a helical structure, starting from the monomer conformation in aqueous solution of fluorinated alcohols49 (Protein Data Bank code 1IYT). Each monomer has two helices, one in the region of residues 8–25 and at residues 28–38. Thus the possibility that charged residues D1, E3, R5 may act as “electrostatic anchors” to keep the peptides in the lipid bilayer.

In Figures 3E and F is shown an Aβ1–40 channel that is essentially helical, modeled starting from the PDB structure 1BA4.52 The N-terminus is mainly unstructured, with the C-terminus forming a long helix in the region of residues 20 to 39. The hydrophobic C-terminus can interact with the lipid tails, and the charged residues can also anchor the structure in the upper membrane leaflet.

Note that these first three cases (i.e., shown in Fig. 3A-F) inherit three successive [G-XXX-G] motifs from the transmembrane region of the amyloid precursor protein. This type of motif is known to promote dimerization of polypeptides via Cα-H· · ·O hydrogen bonds between two segments in a membrane environment29,53—a phenomenon that might occur when the helical parts of the peptides in the amyloid channel interact inside the lipid membrane. This factor could contribute as a further stabilizing interaction between the channel subunits.

Finally, in Figure 3G and H is shown an Aβ9–40 pore-like structure comprising of monomers with a β-turn-β structural motif, closely related to the structures that have been pioneered and studied extensively by Nussinov et al.43-47

Concluding Remarks and Outlook

Aβ peptides have an amphipathic-like nature and can become associated with neuronal membranes and affect their biological function, resulting in the disruption of ion (e.g., calcium) homeostasis. Presenting only residual secondary structure in solution,54 Aβ monomers have been shown to undergo a membrane-induced conformational change to either primarily β-sheets or to helical structures, depending, among other factors, on the peptide concentration and model membrane composition.55,56 Several studies showed that Aβ association to lipid bilayers renders them permeable to ions but it is not established if this is due to the formation of discrete transmembrane ion channels of Aβ peptide aggregates, to larger pores,57 or to a non-specific perturbation of bilayer integrity by lipid headgroup-associated Aβ peptides. Our MD-based studies do support the former hypothesis, but do not exclude the latter.19 By using atomistic modeling of the interactions between Aβ protofilament segments and lipid bilayers, we showed that Aβ peptides are first subject to strong electrostatic interactions with the lipid headgroups, which facilitate subsequent hydrophobic interactions between the Aβ C-termini and the lipid tails. This mechanism leads to a significant loss of the rich β-sheet content characteristic to Aβ fibrillar oligomers and protofilaments in water,20,21 and has further consequences on modeling the molecular structures of membrane-absorbed fibrillar oligomers and amyloid channels. While not dismissing the possibility that in certain conditions membrane-incorporated Aβ aggregates may present a similar β-turn-β structural motif with their fibrillar water-formed counterparts, our studies suggest that this would require a rather special mechanism that would protect the fibrillar structures from disruption upon strong interactions with the lipid headgroups. We thus find it more likely that, just as demonstrated before by solid-state NMR studies and MD simulations for regular Aβ fibrils,20,23,32,58 their membrane-bound counterparts may be characterized by a similarly polymorphic nature that could lead to a variety of amyloid channel structures. While it is possible that some of these structures are still stabilized by a large fraction of inter-peptide hydrogen bonds, leading to the formation of β-strands (as illustrated in Fig. 3), they may also present a significant helical content in peptide regions (e.g., termini) that are subject to interactions with lipid tails rather than with neighboring Aβ peptides. Due to their implications in understanding the molecular processes that lead to the cytotoxicity of amyloid fibrils, oligomers and channels, we expect that structural studies using both modern experimental and computational techniques will continue to be central to amyloid-related research.19,24-26,30,32,47,55-57,59-71

Acknowledgments

We thank Gerhard Hummer, John Straub, Attila Szabo, and Robert Tycko for helpful discussions. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Irish Research Council for Science, Engineering and Technology (IRCSET), and the use of computational facilities provided by the Irish Centre for High-End Computing (ICHEC).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- MD

molecular dynamics

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- POPE

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- POPC

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- COM

center of mass

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/prion/article/21022

References

- 1.Yankner BA, Duffy LK, Kirschner DA. Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid beta protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides. Science. 1990;250:279–82. doi: 10.1126/science.2218531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neve RL, Dawes LR, Yankner BA, Benowitz LI, Rodriguez W, Higgins GA. Genetics and biology of the Alzheimer amyloid precursor. Prog Brain Res. 1990;86:257–67. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)63182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pike CJ, Walencewicz AJ, Glabe CG, Cotman CW. In vitro aging of beta-amyloid protein causes peptide aggregation and neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 1991;563:311–4. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91553-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busciglio J, Lorenzo A, Yankner BA. Methodological variables in the assessment of beta amyloid neurotoxicity. Neurobiol Aging. 1992;13:609–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koh JY, Yang LL, Cotman CW. Beta-amyloid protein increases the vulnerability of cultured cortical neurons to excitotoxic damage. Brain Res. 1990;533:315–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91355-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattson MP, Cheng B, Davis D, Bryant K, Lieberburg I, Rydel RE. beta-Amyloid peptides destabilize calcium homeostasis and render human cortical neurons vulnerable to excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1992;12:376–89. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00376.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer-Luehmann M, Coomaraswamy J, Bolmont T, Kaeser S, Schaefer C, Kilger E, et al. Exogenous induction of cerebral beta-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host. Science. 2006;313:1781–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1131864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisele YS, Obermüller U, Heilbronner G, Baumann F, Kaeser SA, Wolburg H, et al. Peripherally applied Abeta-containing inoculates induce cerebral beta-amyloidosis. Science. 2010;330:980–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1194516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JS, Holtzman DM. Medicine. Prion-like behavior of amyloid-beta. Science. 2010;330:918–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1198314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kremer JJ, Pallitto MM, Sklansky DJ, Murphy RM. Correlation of beta-amyloid aggregate size and hydrophobicity with decreased bilayer fluidity of model membranes. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10309–18. doi: 10.1021/bi0001980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Lins L, Bensliman M, Van Bambeke F, Van Der Smissen P, Peuvot J, et al. Membrane destabilization induced by beta-amyloid peptide 29-42: importance of the amino-terminus. Chem Phys Lipids. 2002;120:57–74. doi: 10.1016/S0009-3084(02)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glabe CG. Amyloid Oligomer Structures and Toxicity. The Open Biology Journal. 2010;2:222–7. doi: 10.2174/1874196700902020222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demuro A, Mina E, Kayed R, Milton SC, Parker I, Glabe CG. Calcium dysregulation and membrane disruption as a ubiquitous neurotoxic mechanism of soluble amyloid oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17294–300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kayed R, Sokolov Y, Edmonds B, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Hall JE, et al. Permeabilization of lipid bilayers is a common conformation-dependent activity of soluble amyloid oligomers in protein misfolding diseases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46363–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sokolov YV, Kayed R, Kozak A, Edmonds B, McIntire TM, Milton S, et al. Soluble amyloid oligomers increase lipid bilayer conductance by increasing the dielectric constant of the hydrocarbon core. Biophys J. 2004;86:382a. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arispe N, Pollard HB, Rojas E. Beta-Amyloid Ca2+-Channel Hypothesis for Neuronal Death in Alzheimer-Disease. J Gen Physiol. 1994;104:A31–2. doi: 10.1007/BF00926750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lashuel HA, Hartley D, Petre BM, Walz T, Lansbury PT., Jr. Neurodegenerative disease: amyloid pores from pathogenic mutations. Nature. 2002;418:291–291. doi: 10.1038/418291a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau TL, Ambroggio EE, Tew DJ, Cappai R, Masters CL, Fidelio GD, et al. Amyloid-beta peptide disruption of lipid membranes and the effect of metal ions. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:759–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tofoleanu F, Buchete N-V. Molecular Interactions of Alzheimer’s Aβ Protofilaments with Lipid Membranes. J Mol Biol. 2012;421:572–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchete NV, Tycko R, Hummer G. Molecular dynamics simulations of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid protofilaments. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:804–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchete NV, Hummer G. Structure and dynamics of parallel beta-sheets, hydrophobic core, and loops in Alzheimer’s A beta fibrils. Biophys J. 2007;92:3032–9. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.100404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petkova AT, Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Delaglio F, et al. A structural model for Alzheimer’s beta -amyloid fibrils based on experimental constraints from solid state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16742–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paravastu AK, Petkova AT, Tycko R. Polymorphic fibril formation by residues 10-40 of the Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid peptide. Biophys J. 2006;90:4618–29. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.076927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petkova AT, Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Delaglio F, et al. A structural model for Alzheimer’s beta -amyloid fibrils based on experimental constraints from solid state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16742–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petkova AT, Yau WM, Tycko R. Experimental constraints on quaternary structure in Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibrils. Biochemistry. 2006;45:498–512. doi: 10.1021/bi051952q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roux B, Schulten K. Computational studies of membrane channels. Structure. 2004;12:1343–51. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen MO, Tajkhorshid E, Schulten K. Electrostatic tuning of permeation and selectivity in aquaporin water channels. Biophys J. 2003;85:2884–99. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74711-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kayed R, Pensalfini A, Margol L, Sokolov Y, Sarsoza F, Head E, et al. Annular protofibrils are a structurally and functionally distinct type of amyloid oligomer. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4230–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808591200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kienlen-Campard P, Tasiaux B, Van Hees J, Li M, Huysseune S, Sato T, et al. Amyloidogenic processing but not amyloid precursor protein (APP) intracellular C-terminal domain production requires a precisely oriented APP dimer assembled by transmembrane GXXXG motifs. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7733–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707142200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gehman JD, O’Brien CC, Shabanpoor F, Wade JD, Separovic F. Metal effects on the membrane interactions of amyloid-β peptides. Eur Biophys J. 2008;37:333–44. doi: 10.1007/s00249-007-0251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Planque MRR, Raussens V, Contera SA, Rijkers DTS, Liskamp RMJ, Ruysschaert JM, et al. beta-Sheet structured beta-amyloid(1-40) perturbs phosphatidylcholine model membranes. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:982–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sani MA, Gehman JD, Separovic F. Lipid matrix plays a role in Abeta fibril kinetics and morphology. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:749–54. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y, Shen J, Luo X, Zhu W, Chen K, Ma J, et al. Conformational transition of amyloid beta-peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5403–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501218102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollard HB, Arispe N, Rojas E. Ion channel hypothesis for Alzheimer amyloid peptide neurotoxicity. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1995;15:513–26. doi: 10.1007/BF02071314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durell SR, Guy HR, Arispe N, Rojas E, Pollard HB. Theoretical models of the ion channel structure of amyloid beta-protein. Biophys J. 1994;67:2137–45. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80717-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quist A, Doudevski I, Lin H, Azimova R, Ng D, Frangione B, et al. Amyloid ion channels: a common structural link for protein-misfolding disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10427–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502066102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhee SK, Quist AP, Lal R. Amyloid beta protein-(1-42) forms calcium-permeable, Zn2+-sensitive channel. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13379–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin H, Bhatia R, Lal R. Amyloid beta protein forms ion channels: implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. FASEB J. 2001;15:2433–44. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0377com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simakova O, Arispe NJ. Early and late cytotoxic effects of external application of the Alzheimer’s Abeta result from the initial formation and function of Abeta ion channels. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5907–15. doi: 10.1021/bi060148g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arispe N, Diaz JC, Flora M. Efficiency of histidine-associating compounds for blocking the alzheimer’s Abeta channel activity and cytotoxicity. Biophys J. 2008;95:4879–89. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.135517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lashuel HA, Hartley DM, Petre BM, Wall JS, Simon MN, Walz T, et al. Mixtures of wild-type and a pathogenic (E22G) form of Abeta40 in vitro accumulate protofibrils, including amyloid pores. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:795–808. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00927-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lal R, Lin H, Quist AP. Amyloid beta ion channel: 3D structure and relevance to amyloid channel paradigm. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:1966–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jang H, Zheng J, Nussinov R. Models of beta-amyloid ion channels in the membrane suggest that channel formation in the bilayer is a dynamic process. Biophys J. 2007;93:1938–49. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.110148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jang H, Zheng J, Lal R, Nussinov R. New structures help the modeling of toxic amyloidbeta ion channels. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jang H, Arce FT, Capone R, Ramachandran S, Lal R, Nussinov R. Misfolded amyloid ion channels present mobile beta-sheet subunits in contrast to conventional ion channels. Biophys J. 2009;97:3029–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jang H, Arce FT, Ramachandran S, Capone R, Lal R, Nussinov R. β-Barrel topology of Alzheimer’s β-amyloid ion channels. J Mol Biol. 2010;404:917–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Connelly L, Jang H, Arce FT, Capone R, Kotler SA, Ramachandran S, et al. Atomic force microscopy and MD simulations reveal pore-like structures of all-D-enantiomer of Alzheimer’s β-amyloid peptide: relevance to the ion channel mechanism of AD pathology. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:1728–35. doi: 10.1021/jp2108126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sticht H, Bayer P, Willbold D, Dames S, Hilbich C, Beyreuther K, et al. Structure of amyloid A4-(1-40)-peptide of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Biochem. 1995;233:293–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.293_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crescenzi O, Tomaselli S, Guerrini R, Salvadori S, D’Ursi AM, Temussi PA, et al. Solution structure of the Alzheimer amyloid beta-peptide (1-42) in an apolar microenvironment. Similarity with a virus fusion domain. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:5642–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyashita N, Straub JE, Thirumalai D. Structures of beta-amyloid peptide 1-40, 1-42, and 1-55-the 672-726 fragment of APP-in a membrane environment with implications for interactions with gamma-secretase. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:17843–52. doi: 10.1021/ja905457d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tomaselli S, Esposito V, Vangone P, van Nuland NAJ, Bonvin AMJJ, Guerrini R, et al. The alpha-to-beta conformational transition of Alzheimer’s Abeta-(1-42) peptide in aqueous media is reversible: a step by step conformational analysis suggests the location of beta conformation seeding. Chembiochem. 2006;7:257–67. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coles M, Bicknell W, Watson AA, Fairlie DP, Craik DJ. Solution structure of amyloid beta-peptide(1-40) in a water-micelle environment. Is the membrane-spanning domain where we think it is? Biochemistry. 1998;37:11064–77. doi: 10.1021/bi972979f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miyashita N, Straub JE, Thirumalai D, Sugita Y. Transmembrane structures of amyloid precursor protein dimer predicted by replica-exchange molecular dynamics simulations. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3438–9. doi: 10.1021/ja809227c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang S, Iwata K, Lachenmann MJ, Peng JW, Li S, Stimson ER, et al. The Alzheimer’s peptide a beta adopts a collapsed coil structure in water. J Struct Biol. 2000;130:130–41. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pallitto MM, Murphy RM. A mathematical model of the kinetics of beta-amyloid fibril growth from the denatured state. Biophys J. 2001;81:1805–22. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75831-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kremer JJ, Murphy RM. Kinetics of adsorption of beta-amyloid peptide Abeta(1-40) to lipid bilayers. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2003;57:159–69. doi: 10.1016/S0165-022X(03)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ambroggio EE, Kim DH, Separovic F, Barrow CJ, Barnham KJ, Bagatolli LA, et al. Surface behavior and lipid interaction of Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide 1-42: a membrane-disrupting peptide. Biophys J. 2005;88:2706–13. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.055582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Petkova AT, Leapman RD, Guo Z, Yau WM, Mattson MP, Tycko R. Self-propagating, molecular-level polymorphism in Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibrils. Science. 2005;307:262–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1105850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu X, Zheng J. Cholesterol Promotes the Interaction of Alzheimer β-Amyloid Monomer with Lipid Bilayer. J Mol Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walters RH, Jacobson KH, Pedersen JA, Murphy RM. Elongation Kinetics of Polyglutamine Peptide Fibrils: A Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation Study. J Mol Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seeliger J, Weise K, Opitz N, Winter R. The Effect of Aβ on IAPP Aggregation in the Presence of an Isolated β-Cell Membrane. J Mol Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murphy RD, Conlon J, Mansoor T, Luca S, Vaiana SM, Buchete N-V. Conformational dynamics of human IAPP monomers. Biophys Chem. 2012;167C:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Laganowsky A, Liu C, Sawaya MR, Whitelegge JP, Park J, Zhao M, et al. Atomic view of a toxic amyloid small oligomer. Science. 2012;335:1228–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1213151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kapurniotu A. Shedding light on Alzheimer’s β-amyloid aggregation with chemical tools. Chembiochem. 2012;13:27–9. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Berezhkovskii AM, Tofoleanu F, Buchete NV. Are Peptides Good Two-State Folders? J Chem Theory Comput. 2011;7:2370–5. doi: 10.1021/ct200281d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fändrich M. Oligomeric Intermediates in Amyloid Formation: Structure Determination and Mechanisms of Toxicity. J Mol Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buchete NV, Straub JE, Thirumalai D. Dissecting contact potentials for proteins: relative contributions of individual amino acids. Proteins. 2008;70:119–30. doi: 10.1002/prot.21538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bemporad F, Chiti F. Protein Misfolded Oligomers: Experimental Approaches, Mechanism of Formation, and Structure-Toxicity Relationships. Chemistry &. Biology. 2012;19:315–27. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xiao D, Fu L, Liu J, Batista VS, Yan ECY. Amphiphilic Adsorption of Human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide Aggregates to Lipid/Aqueous Interfaces. J Mol Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Buchner GS, Murphy RD, Buchete NV, Kubelka J. Dynamics of protein folding: probing the kinetic network of folding-unfolding transitions with experiment and theory. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814:1001–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu JX, Yau WM, Tycko R. Evidence from solid-state NMR for nonhelical conformations in the transmembrane domain of the amyloid precursor protein. Biophys J. 2011;100:711–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.12.3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]