Abstract

Aberrant activation of Cdk5 has been implicated in the process of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (AD). We recently reported that S-nitrosylation of Cdk5 (forming SNO-Cdk5) at specific cysteine residues results in excessive activation of Cdk5, contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction, synaptic damage, and neuronal cell death in models of AD. Furthermore, SNO-Cdk5 acts as a nascent S-nitrosylase, transnitrosylating the mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 and enhancing excessive mitochondrial fission in dendritic spines. However, a molecular mechanism that leads to the formation of SNO-Cdk5 in neuronal cells remained obscure. Here, we demonstrate that neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS1) interacts with Cdk5 and that the close proximity of the two proteins facilitates the formation of SNO-Cdk5. Interestingly, as a negative feedback mechanism, Cdk5 phosphorylates and suppresses NOS1 activity. Thus, together with our previous report, these findings delineate an S-nitrosylation pathway wherein Cdk5/NOS1 interaction enhances SNO-Cdk5 formation, mediating mitochondrial dysfunction and synaptic loss during the etiology of AD.

Keywords: nitrosative stress, Cyclin-dependent kinase 5, nitric oxide, neuronal NO synthase, transnitrosylation

Cdk5 in Alzheimer's disease and other neurological disorders

Cdk5 is a unique cyclin-dependent serine/threonine kinase that is activated by the two neuron-specific proteins p35 and p39.1-3 As a predominantly neuronal-specific kinase, Cdk5 is believed to lack a role in cell-cycle control but regulates an array of neuronal functions, including neuronal survival, axon and dendrite development, spine morphology, and neuronal migration.4-6 Dysregulation of Cdk5 activity has been implicated in stroke and many neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.7-13 Under these neurodegenerative conditions, neurotoxic stimuli such as oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, excitotoxicity, amyloid-β (Aβ) exposure, calcium overload, and neuroinflammation trigger the hyperactivation of Cdk5 via the calcium-dependent protease calpain, which cleaves the Cdk5 activator p35 (or p39) into p25 (or p29).14-18 Thus, the accumulation of p25, due to the conversion of p35 to p25 (or p39 to p29), activates various events associated with neurodegeneration. Along with these lines, a p25 transgenic mouse line, wherein p25 expression is driven under the tetracycline-controlled CaMKII promoter, manifests AD-like neurodegeneration associated with Aβ accumulation, brain atrophy, astrogliosis, substantial neuronal loss, and neurofibrillary tangle pathology.19,20 Moreover, Cdk5 is known to phosphorylate amyloid precursor protein (APP), affecting its localization or processing to Aβ peptide; moreover, Aβ accumulation triggers Cdk5/p25 hyperactivation possibly via an N-methyl-d-aspartate-type glutamate receptor (NMDAR) cascade.21,22 However, despite the fact that AD patient brains manifest significantly higher Cdk5 activity compared with non-demented control brains, whether the increased Cdk5 activity is due to the elevated levels of p25 in AD remains a contentious issue.23 Hence, additional regulatory mechanisms for Cdk5 under neurodegenerative conditions remain to be determined.

S-Nitrosylation as a novel mechanism of Cdk5 activation

It is well known that nitric oxide (NO) or related species can contribute to a number of neurodegenerative diseases including AD, PD and HD. In neurons, NO generated from NOS1 (neuronal NO synthase) appears to play critical roles in mitochondrial dysfunction, protein misfolding, synaptic loss, and neuronal cell death.24 Increased levels of neuronal Ca2+, in conjunction with the Ca2+-binding protein calmodulin, trigger the activation of NOS1 and subsequent generation of NO from the amino acid l-arginine.25-27 Additionally, NOS1 contains an N-terminal PDZ domain, allowing NOS1 to couple to postsynaptic density protein (PSD)-95 and a variety of ion channels, including the NMDAR.27,28 Consequently, increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration in response to specific pathological stress, such as excitotoxicity, can stimulate NO production from NOS1 at via NMDAR activation.

Historically, activation of soluble guanylate cyclase to form cGMP was recognized as an important cellular signal to mediate the biological activity of NO. However, emerging evidence suggests that the reaction of an NO group with the critical cysteine thiol of target proteins to form S-nitrosoproteins represents the major regulatory mechanism of NO action, particularly in neurodegenerative conditions.24,29 Our group and others have identified specific substrates for S-nitrosylation under neurodegenerative conditions, including the protein folding/chaperone enzyme protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), the ubiquitin E3 ligase/neuroprotectant protein parkin, and the mitochondrial fission-inducing protein Drp1.24,30-33 Along similar lines, we recently reported that S-nitrosylation of Cdk5 at cysteine residues 83 and 157 activates its kinase activity,34 leading to an increase in phosphorylated proteins, including the pro-apoptotic serine/threonine-specific protein kinase, ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM).4,35 Importantly, we showed that S-nitrosylation and hyperactivation of Cdk5 mediates Aβ- or NMDA-induced dendritic spine loss, supporting our hypothesis that SNO-Cdk5 contributes to AD pathology (see detailed discussion below). Furthermore, our findings of S-nitrosylated Cdk5 occurring in human brains with AD as well as in AD model mice, but not in control human or mouse brains, support our notion that SNO-Cdk5 formation represents an aberrant NO pathway leading to pathological disease conditions. Interestingly, we found that SNO-Cdk5 might contribute to synaptic failure via transfer of the NO group to Drp1 by a reaction known as transnitrosylation. The resulting formation of S-nitrosylated Drp1 triggers excessive mitochondrial fission, which is associated with bioenergetic compromise in the synapses, contributing to dendritic spine loss, as we have previously demonstrated.30 Thus, these findings indicate that Cdk5 may be a dual function enzyme, mediating both phosphorylation as a kinase and transnitrosylation as a nitrosylase, and elucidate a new regulatory mechanism of Cdk5 that may be involved in the etiology of Alzheimer-related mitochondrial dysfunction and synaptic pathology.

Cdk5 Interacts with NOS1

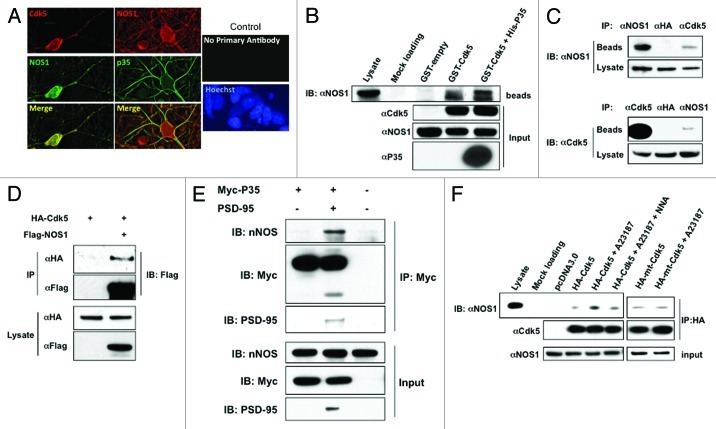

In general, NO generated from NOS efficiently S-nitrosylates nearby proteins to produce SNO-proteins. For example, NMDARs and PSD-95 co-localize with NOS1, and are good substrates for S-nitrosylation.29,36 Having shown that S-nitrosylation of Cdk5 was upregulated by stimulation of NOS1,34 we hypothesized that Cdk5 might interact directly with NOS1. This possibility seemed reasonable because Cdk5 is targeted to the plasma membrane by its co-activator p35,37 and NOS1 is also localized to the plasma membrane. Along these lines, in immunocytochemical experiments, we found that both p35 and Cdk5 displayed a similar subcellular distribution to NOS1 (Fig. 1A). Additionally, in an in vitro glutathione-S-transferase (GST) pull-down assay, GST fused to Cdk5 pulled down NOS1 from rat brain homogenates, and addition of His-p35 resulted in a slight increase in NOS1 (Fig. 1B). To further investigate whether Cdk5 and NOS1 bind together in vivo, we tested if anti-Cdk5 antibody could immunoprecipitate NOS1 from rat brain homogenates, and, conversely, if anti-NOS1 could immunoprecipitate Cdk5. We detected NOS1 in Cdk5 immunoprecipitates, and Cdk5 in NOS1 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that Cdk5 and NOS1 can form a complex in vivo.

Figure 1. Cdk5 Interacts with NOS1. (A) Co-localization of NOS1 and Cdk5 in rat cerebrocortical neurons. NOS1 and Cdk5 were detected by immunocytochemistry in cultures after 14 d in vitro. Cdk5 and NOS1 staining superimpose to show co-localization in deconvolved images. Rat cerebrocortical neurons were also stained with anti-p35 antibody. No staining was observed when primary antibodies were omitted. (B) GST-pull down assay. GST-fusion protein or GST alone (GST-empty) was incubated with rat brain homogenates for 3–5 h and then pulled down with GSH beads. The precipitates were subjected to immunoblot and probed with NOS1 antibody. GST-Cdk5 or GST-Cdk5 plus His-p35, but not GST protein alone, pulled down NOS1 (lanes 4 and 5). (C) Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) of NOS1 and Cdk5 from rat brain homogenates. Homogenates were immunoprecipitated with Cdk5 or NOS1 antibody and then probed with these antibodies. Anti-HA antibody was used as a control. (D) Interaction of Cdk5 and NOS1 is independent of p35. HEK293T cells were transfected as indicated, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag or anti-HA antibody. Precipitates and total lysates were subjected to immunoblotting. (E) p35 does not directly interact with NOS1. HEK293-NOS1 cells were transfected as indicated, lysed and, immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody. Precipitates and total lysate were subjected to immunoblotting. (F) Co-IP of NOS1 and Cdk5 in HEK293-NOS1 cells. HEK293-NOS1 cells transfected with HA-tagged Cdk5, HA-tagged mtCdk5 (non-nitrosylatable mutant), or pcDNA3.0 were treated with 5 μM A23187 in the presence or absence of 1 mM N-nitro-l-arginine (NNA), immunoprecipitated with HA antibody, and then probed with NOS1 antibody.

Next, since the Cdk5 co-activator p35 can bind via PDZ domains to PSD95, forming a complex with the NMDAR and NOS1,13,38 we asked if the association of Cdk5 with NOS1 was dependent on p35. To exclude this possibility, we tested the interaction between NOS1 and Cdk5 in HEK 293T cells transfected with hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Cdk5 plus Flag-tagged NOS1 in the absence of endogenous PSD95, p35 or NMDAR subunits.39-41 Under these conditions, Cdk5 was still detected in anti-Flag antibody immunoprecipitates (Fig. 1D). Additionally, p35 itself did not interact with NOS1 in an overexpression system unless PSD95 was also expressed (Fig. 1E). These results strongly support the notion that under our conditions the association of Cdk5 and NOS1 was not mediated via p35.

We next investigated whether association of NOS1 and Cdk5 could be enhanced by NOS1 stimulation. We found more significant recruitment of Cdk5 to NOS1 in HEK293 cells stably expressing NOS1 (HEK-NOS1) after treatment with A23187 to activate NOS1 via Ca2+ influx (Fig. 1F), and this enhancement was largely abolished by the NOS inhibitor, N-nitro-l-arginine (NNA). Additionally, A23187 failed to increase NOS1 binding to mutant Cdk5 lacking nitrosylation sites. These results are consistent with the notion that NOS1-generated NO increases the interaction of Cdk5 with NOS1 via S-nitrosylation of Cdk5.

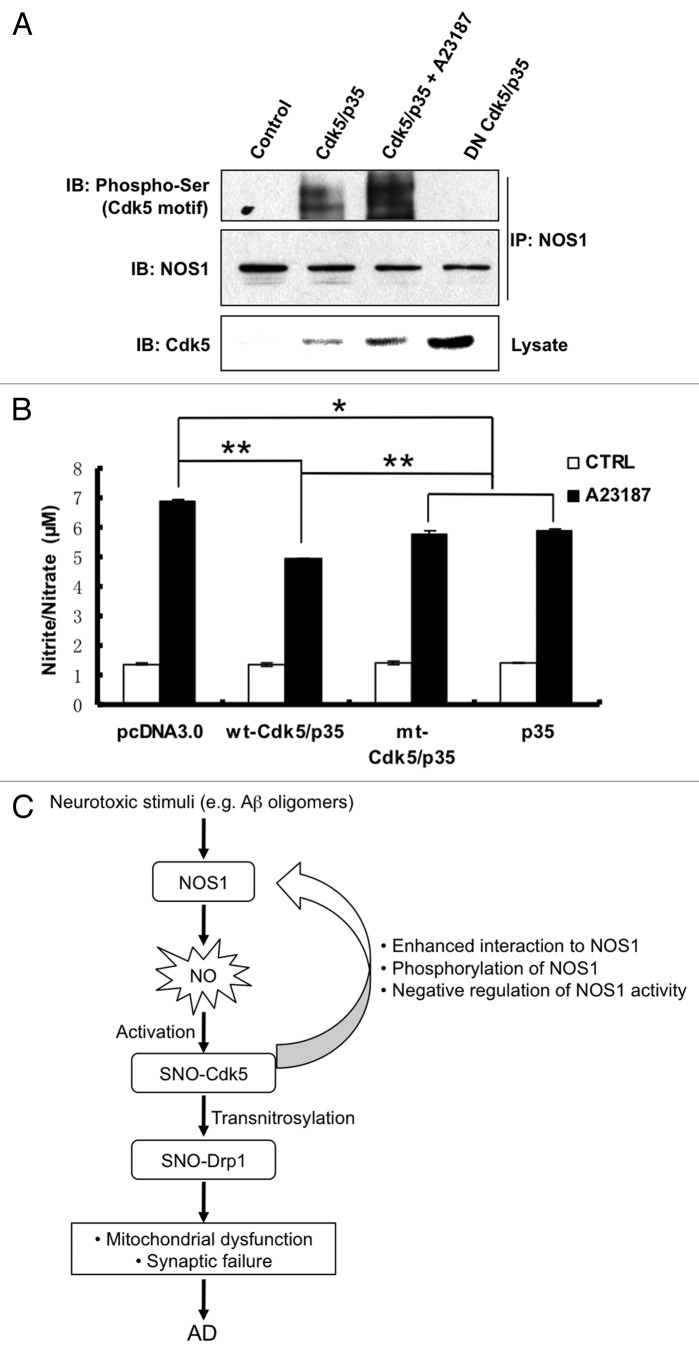

S-Nitrosylation of Cdk5 Triggers Phosphorylation of NOS1

Additionally, we found evidence for negative-feedback control of NOS1 activity by SNO-Cdk5. Initially, we noted the presence of several potential Cdk5 phosphorylation sites in the NOS1 sequence. For example, Ser292 and Ser298 are located in a consensus proline-directed kinase motif [(K/R) S/T* P X (K/R)].42 Therefore, we investigated whether NOS1 was phosphorylated by Cdk5 on these serines. We used anti-NOS1 antibody to immunoprecipitate total NOS1 protein, and then probed for phosphorylated NOS1 on immunoblots using anti-phosphorylated serine/Cdk5 motif antibody. We found that overexpression of Cdk5/p35 induced phosphorylation of NOS1, and that this effect was abrogated by overexpression of dominant negative Cdk5(D145N) (Fig. 2A). Moreover, calcium-activation of NOS1 with A23187 resulted in SNO-Cdk5 formation, upregulation of Cdk5 activity, and further enhancement of NOS1 phosphorylation. Analysis of the primary structure of NOS1 revealed two potential phosphorylation sites on NOS1 localized within the oxygenase domain, suggesting that phosphorylation by Cdk5 might modify NOS1 enzymatic activity. To confirm this supposition, we employed the Griess assay to monitor reactive nitrogen species (RNS) production by NOS1 in HEK-NOS1 cells. We found that Cdk5/p35 overexpression significantly suppressed RNS production and hence NOS1 activity induced by A23187 (Fig. 2B). The non-nitrosylatable mutant of Cdk5 (mt-Cdk5) suppressed NOS1 activity to a lesser extent than wild-type (wt-Cdk5). Taken together, these data are consistent with the notion that activation of NOS1 led to S-nitrosylation and hence activation of Cdk5. In turn, activated Cdk5 phosphorylated NOS1, thus suppressing its activity in a negative regulatory-feedback loop.

Figure 2. NOS1 phosphorylation by Cdk5 suppresses NOS1 activity. (A) Increased phosphorylation of NOS1 by activated Cdk5. HEK293-NOS1 stably transformed cells were transfected with pcDNA3.0, wt-Cdk5 plus p35, or DN-Cdk5 plus p35 plasmids and exposed to 5 μM A23187 or control solution. Cells were then lysed and immunoprecipitated with NOS1 antibody. Precipitates and total lysates were subjected to western blot with the antibodies indicated. (B) NOS1 activity is suppressed by Cdk5. HEK293-NOS1 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.0, wild-type (wt) Cdk5 plus p35, or cysteine-mutant (mt) Cdk5 plus p35 plasmids. Cells were exposed to 5 μM A23187 or control solution; 30 min later, cell media were collected and subjected to Griess assay for nitrite/nitrate levels. Values are mean ± SEM (t-test, n > 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with wt-Cdk5/p35 + A23187). (C) Schema of the SNO-Cdk5 signaling pathway in AD. Activation of Cdk5 by S-nitrosylation enhances its interaction with NOS1. SNO-Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of NOS1 suppresses its activity, representing negative feedback regulation of NOS1 function. Transfer of NO from SNO-Cdk5 to Drp1 mediates the formation of SNO-Drp1, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction and dendritic spine loss.

S-Nitrosylase activity of Cdk5 links nitrosative stress to mitochondrial dysfunction-mediated synaptic damage

Previously, we reported that excessive generation of RNS increases Cdk5 kinase activity via S-nitrosylation and identified two cysteine residues (Cys 83 and 157) on Ckd5 that could be S-nitrosylated by NO.34 In contrast, another group presented evidence that Cdk5 activity can be regulated during neuronal development via S-nitrosylation but reported that NO could inhibit rather than activate Cdk5.43 As we showed previously, this discrepancy may have arisen because of the very high concentration of NO donor used by the other group.34 In the present study, we demonstrate that NOS1 binds to Cdk5 in neurons. The resulting close proximity of NOS1 to Cdk5 may facilitate endogenous NO reacting to form SNO-Cdk5. Moreover, as stated above, we mount evidence that NOS1, similar to NOS3,44 serves as a Cdk5 substrate, creating a negative-feedback loop by suppressing NOS1 activity, NO production, and thus Cdk5 activity. However, under pathological conditions with increased NOS1 activity, we observed an enhanced association between NOS1 and Cdk5, which may facilitate SNO-Cdk5 formation, resulting in increased Cdk5 activity.

In a prior report, we also showed that S-nitrosylation of Cdk5 contributes to dendritic spine loss and neuronal cell death. Under pathological conditions, abnormal dendritic spine morphology and decreased number, representing synaptic loss, have been found to closely correlate with the severity of cognitive decline in Alzheimer and other neurological diseases.45-48 We found that SNO-Cdk5 mediates, at least in part, amyloid-β peptide (Aβ)-induced spine loss in cellular models of AD. Moreover, we found that expression of mutant, non-nitrosylatable Cdk5 significantly ameliorated spine retraction during excitotoxic stress or oligomeric Aβ exposure. These findings suggest that SNO-Cdk5 may represent a novel therapeutic target for alleviating spine damage in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative conditions.

However, the molecular pathway whereby SNO-Cdk5 mediates synaptic abnormality remained elusive until we discovered the relationship of SNO-Cdk5 and the mitochondrial fission protein dynamin related protein 1 (Drp1). Intriguingly, prior reports had implicated that Cdk5 could trigger excessive mitochondrial fission involving Drp1, and it was suggested that Drp1 might possibly be a substrate for Cdk5 regulation but no phosphorylation event could be detected.49 Moreover, our group recently discovered that S-nitrosylation of Drp1 at Cys644 hyperactivates its mitochondrial fission activity, thus mediating Aβ-induced disruption of mitochondrial dynamics, compromise of mitochondrial bioenergetics, and consequent synaptic injury and neuronal damage.30 Linking these events, we recently found evidence that SNO-Cdk5 transnitrosylates Drp1 both in vitro and in intact cells, with consequent formation of SNO-Drp1. These findings suggest that, in addition to its kinase activity, SNO-Cdk5 manifests nitrosylase activity, contributing to synaptic damage via transfer of the NO group to Drp1, with consequent fragmentation of mitochondria and synaptic loss.

In healthy neurons, mitochondrial fission/fusion machinery proteins insure that new, active mitochondria are generated at critical locations, such as synapses, while maintaining mitochondrial integrity. In contrast, abnormal mitochondrial dynamics often appear in the degenerative brain as a result of dysfunction in the fission/fusion machinery. Rare genetic mutations in the genes encoding mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins disturb mitochondrial dynamics, causing neurological defects, including certain forms of peripheral neuropathy, ataxia, and optic atrophy.50-56 Both mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins are widely expressed in human tissues but defects preferentially affect nervous tissue, suggesting that neurons are particularly sensitive to mitochondrial dysfunction. We previously reported that S-nitrosylation of Drp1 results in hyperactivation and excessive mitochondrial fission. Moreover, similar to SNO-Cdk5, we observed that Drp1 is S-nitrosylated in virtually all of the brains from cases of sporadic AD that we examined.30,57 We found that in response to Aβ, SNO-Drp1 induces excessive mitochondrial fragmentation, producing synaptic damage, an early characteristic feature of AD, and subsequently apoptotic neuronal cell death. Importantly, prevention of Drp1 nitrosylation [using the non-nitrosylatable Drp1(C644A) mutant] prevented Aβ-mediated mitochondrial fission, synaptic loss, and neuronal cell death, suggesting that S-nitrosylation of Drp1 contributes to the pathogenesis of AD. Moreover, we found that SNO-Drp1 is generated by the specific Drp1 nitrosylase activity of SNO-Cdk5, transferring the NO group from Cdk5 to Drp1, and thus contributing to neuronal injury and synaptic loss in AD.

Conclusions and Further Perspectives

In conjunction with our recent report,34 in the present study, we have uncovered an NO signaling pathway wherein (1) NOS1 generates NO in response to exposure to excitotoxins or oligomeric Aβ, (2) NO can S-nitrosylate the NOS-interacting protein, Cdk5, resulting in activation of its kinase activity, (3) as a negative feedback mechanism, SNO-Cdk5 phosphorylates and inhibits NOS1, (4) SNO-Cdk5 hyperactivates the mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 via transnitrosylation, and (5) excessive mitochondrial fission results in bioenergetic failure and synaptic loss in AD (Fig. 2C). One important finding of these studies is that Cdk5 possesses both kinase and nitrosylase activities, suggesting that this dual function of Cdk5 could be involved in neurodegeneration. Given the fact that Cdk5 phosphorylates a number of target substrate proteins,58 it is possible that Cdk5 also nitrosylates other substrates. Furthermore, dysregulation of Cdk5 activity may play a role not only in AD but also in several other neurodegenerative disorders, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, Huntington’s disease, and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.7,11,59,60 Thus, our finding that SNO-Cdk5 mediates neuronal injury may be important not only in AD but also in these other neurological diseases. Moreover, this SNO-Cdk5 signaling pathway may represent a potential target for therapeutic intervention in these disorders.

Experimental Procedures

Antibodies and Plasmids

Cdk5 polyclonal antibody (C-8), NOS1 monoclonal antibody (A-11), anti-HA antibody, and anti-myc antibody were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; anti-phosphorylated serine/Cdk5 motif antibody was from Cell Signaling Technology. HA-Cdk5, HA-DN-Cdk5 and Myc-p35 plasmids were from Addgene. Flag-NOS1 was kindly provided by Prof. Yasuo Watanabe (Nippon Institute of Technology, Japan). GST-Cdk5 and His-p35 plasmids were kindly provided by Prof. David Park (University of Ottawa, Canada).

Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. HEK293-NOS1 cells were maintained in the same medium containing geneticin. We performed cell transfections with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Primary cerebrocortical neurons were cultured from day 16 rat embryos as we have described previously.30,32

GST-Pull Down Assay

GST-Cdk5 and His-p35 were expressed in E. coli and purified as described.11 Purified GST or GST-Cdk5 was incubated with rat brain homogenate for 3 h and then subjected to precipitation using glutathione-Sepharose followed by anti-NOS1 antibody.

Immunoblot Analysis and Immunoprecipitation

Twenty micrograms of protein were electrophoresed on 4–12% denaturing gels (Nupage, Invitrogen). After transferring the proteins to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immoblin-P, Millipore), immunoblot analyses were performed using various primary antibodies and HRP-labeled secondary antibodies. For immunoprecipitation, 100 µg of cell lysate was incubated with a complex of protein A/G-agarose beads and primary antibody (or with antibody immobilized on the beads) for 3–5 h at 4°C. Beads were then washed with lysis buffer three times and subjected to immunoblot or kinase assays.

Detection of NO by Griess Assay

An aliquot of the culture medium from experimental cells was mixed with Griess reagent for detecting nitrite and nitrate, major conversion products of NO. Quantification was achieved by optical density measurement of nitrite-azo dye formed in the sample, as measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm.61

Statistical Methods

Experiments were performed ≥ 3 times. Statistical differences between two groups were analyzed by Student’s t-test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Traci Newmeyer for preparation of primary cultures. This work was supported in part by funding from Alzheimer Association to T.N., and by NIH grants P01 HD29587, P01 ES016738, R01 EY09024, R01 EY05477, and P30 NS057096 and DoD award W81XWH-10–1-0093 to S.A.L.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/prion/article/21250

References

- 1.Lew J, Huang QQ, Qi Z, Winkfein RJ, Aebersold R, Hunt T, et al. A brain-specific activator of cyclin-dependent kinase 5. Nature. 1994;371:423–6. doi: 10.1038/371423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang D, Yeung J, Lee KY, Matsushita M, Matsui H, Tomizawa K, et al. An isoform of the neuronal cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) activator. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26897–903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai LH, Lee MS, Cruz J. Cdk5, a therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1697:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim Y, Sung JY, Ceglia I, Lee KW, Ahn JH, Halford JM, et al. Phosphorylation of WAVE1 regulates actin polymerization and dendritic spine morphology. Nature. 2006;442:814–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohshima T, Ward JM, Huh CG, Longenecker G, Veeranna, Pant HC, et al. Targeted disruption of the cyclin-dependent kinase 5 gene results in abnormal corticogenesis, neuronal pathology and perinatal death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11173–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie Z, Sanada K, Samuels BA, Shih H, Tsai LH. Serine 732 phosphorylation of FAK by Cdk5 is important for microtubule organization, nuclear movement, and neuronal migration. Cell. 2003;114:469–82. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00605-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patrick C, Crews L, Desplats P, Dumaop W, Rockenstein E, Achim CL, et al. Increased CDK5 expression in HIV encephalitis contributes to neurodegeneration via tau phosphorylation and is reversed with Roscovitine. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1646–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen MD, Larivière RC, Julien JP. Deregulation of Cdk5 in a mouse model of ALS: toxicity alleviated by perikaryal neurofilament inclusions. Neuron. 2001;30:135–47. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paoletti P, Vila I, Rifé M, Lizcano JM, Alberch J, Ginés S. Dopaminergic and glutamatergic signaling crosstalk in Huntington’s disease neurodegeneration: the role of p25/cyclin-dependent kinase 5. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10090–101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3237-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patrick GN, Zukerberg L, Nikolic M, de la Monte S, Dikkes P, Tsai LH. Conversion of p35 to p25 deregulates Cdk5 activity and promotes neurodegeneration. Nature. 1999;402:615–22. doi: 10.1038/45159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qu D, Rashidian J, Mount MP, Aleyasin H, Parsanejad M, Lira A, et al. Role of Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of Prx2 in MPTP toxicity and Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2007;55:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith PD, Crocker SJ, Jackson-Lewis V, Jordan-Sciutto KL, Hayley S, Mount MP, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 is a mediator of dopaminergic neuron loss in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13650–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232515100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Liu S, Fu Y, Wang JH, Lu Y. Cdk5 activation induces hippocampal CA1 cell death by directly phosphorylating NMDA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1039–47. doi: 10.1038/nn1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitazawa M, Oddo S, Yamasaki TR, Green KN, LaFerla FM. Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation exacerbates tau pathology by a cyclin-dependent kinase 5-mediated pathway in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8843–53. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2868-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee MS, Kwon YT, Li M, Peng J, Friedlander RM, Tsai LH. Neurotoxicity induces cleavage of p35 to p25 by calpain. Nature. 2000;405:360–4. doi: 10.1038/35012636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahlgren CM, Pallari HM, He T, Chou YH, Goldman RD, Eriksson JE. A nestin scaffold links Cdk5/p35 signaling to oxidant-induced cell death. EMBO J. 2006;25:4808–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strocchi P, Pession A, Dozza B. Up-regulation of cDK5/p35 by oxidative stress in human neuroblastoma IMR-32 cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:758–65. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zambrano CA, Egaña JT, Núñez MT, Maccioni RB, González-Billault C. Oxidative stress promotes tau dephosphorylation in neuronal cells: the roles of cdk5 and PP1. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:1393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruz JC, Kim D, Moy LY, Dobbin MM, Sun X, Bronson RT, et al. p25/cyclin-dependent kinase 5 induces production and intraneuronal accumulation of amyloid beta in vivo. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10536–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3133-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruz JC, Tseng HC, Goldman JA, Shih H, Tsai LH. Aberrant Cdk5 activation by p25 triggers pathological events leading to neurodegeneration and neurofibrillary tangles. Neuron. 2003;40:471–83. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00627-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otth C, Concha II, Arendt T, Stieler J, Schliebs R, González-Billault C, et al. AbetaPP induces cdk5-dependent tau hyperphosphorylation in transgenic mice Tg2576. J Alzheimers Dis. 2002;4:417–30. doi: 10.3233/jad-2002-4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iijima K, Ando K, Takeda S, Satoh Y, Seki T, Itohara S, et al. Neuron-specific phosphorylation of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid precursor protein by cyclin-dependent kinase 5. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1085–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer A, Sananbenesi F, Pang PT, Lu B, Tsai LH. Opposing roles of transient and prolonged expression of p25 in synaptic plasticity and hippocampus-dependent memory. Neuron. 2005;48:825–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura T, Lipton SA. S-Nitrosylation and uncompetitive/fast off-rate (UFO) drug therapy in neurodegenerative disorders of protein misfolding. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1305–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abu-Soud HM, Stuehr DJ. Nitric oxide synthases reveal a role for calmodulin in controlling electron transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10769–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bredt DS, Hwang PM, Glatt CE, Lowenstein C, Reed RR, Snyder SH. Cloned and expressed nitric oxide synthase structurally resembles cytochrome P-450 reductase. Nature. 1991;351:714–8. doi: 10.1038/351714a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sattler R, Xiong Z, Lu WY, Hafner M, MacDonald JF, Tymianski M. Specific coupling of NMDA receptor activation to nitric oxide neurotoxicity by PSD-95 protein. Science. 1999;284:1845–8. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim E, Sheng M. PDZ domain proteins of synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:771–81. doi: 10.1038/nrn1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipton SA, Choi YB, Pan ZH, Lei SZ, Chen HS, Sucher NJ, et al. A redox-based mechanism for the neuroprotective and neurodestructive effects of nitric oxide and related nitroso-compounds. Nature. 1993;364:626–32. doi: 10.1038/364626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho DH, Nakamura T, Fang J, Cieplak P, Godzik A, Gu Z, et al. S-nitrosylation of Drp1 mediates beta-amyloid-related mitochondrial fission and neuronal injury. Science. 2009;324:102–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1171091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung KK, Thomas B, Li X, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Marsh L, et al. S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates ubiquitination and compromises parkin’s protective function. Science. 2004;304:1328–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1093891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uehara T, Nakamura T, Yao D, Shi ZQ, Gu Z, Ma Y, et al. S-nitrosylated protein-disulphide isomerase links protein misfolding to neurodegeneration. Nature. 2006;441:513–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao D, Gu Z, Nakamura T, Shi ZQ, Ma Y, Gaston B, et al. Nitrosative stress linked to sporadic Parkinson’s disease: S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10810–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404161101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qu J, Nakamura T, Cao G, Holland EA, McKercher SR, Lipton SA. S-Nitrosylation activates Cdk5 and contributes to synaptic spine loss induced by β-amyloid peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14330–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105172108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian B, Yang Q, Mao Z. Phosphorylation of ATM by Cdk5 mediates DNA damage signalling and regulates neuronal death. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:211–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho GP, Selvakumar B, Mukai J, Hester LD, Wang Y, Gogos JA, et al. S-nitrosylation and S-palmitoylation reciprocally regulate synaptic targeting of PSD-95. Neuron. 2011;71:131–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asada A, Yamamoto N, Gohda M, Saito T, Hayashi N, Hisanaga S. Myristoylation of p39 and p35 is a determinant of cytoplasmic or nuclear localization of active cyclin-dependent kinase 5 complexes. J Neurochem. 2008;106:1325–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morabito MA, Sheng M, Tsai LH. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 phosphorylates the N-terminal domain of the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 in neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:865–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4582-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng YL, Li BS, Amin ND, Albers W, Pant HC. A peptide derived from cyclin-dependent kinase activator (p35) specifically inhibits Cdk5 activity and phosphorylation of tau protein in transfected cells. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:4427–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang YZ, Won S, Ali DW, Wang Q, Tanowitz M, Du QS, et al. Regulation of neuregulin signaling by PSD-95 interacting with ErbB4 at CNS synapses. Neuron. 2000;26:443–55. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ehlers MD, Zhang S, Bernhadt JP, Huganir RL. Inactivation of NMDA receptors by direct interaction of calmodulin with the NR1 subunit. Cell. 1996;84:745–55. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vulliet R, Halloran SM, Braun RK, Smith AJ, Lee G. Proline-directed phosphorylation of human Tau protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22570–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang P, Yu PC, Tsang AH, Chen Y, Fu AK, Fu WY, et al. S-nitrosylation of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (cdk5) regulates its kinase activity and dendrite growth during neuronal development. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14366–70. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3899-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho DH, Seo J, Park JH, Jo C, Choi YJ, Soh JW, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 phosphorylates endothelial nitric oxide synthase at serine 116. Hypertension. 2010;55:345–52. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lue LF, Kuo YM, Roher AE, Brachova L, Shen Y, Sue L, et al. Soluble amyloid beta peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:853–62. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65184-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLean CA, Cherny RA, Fraser FW, Fuller SJ, Smith MJ, Beyreuther K, et al. Soluble pool of Abeta amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:860–6. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199912)46:6<860::AID-ANA8>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R, et al. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:572–80. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Penzes P, Cahill ME, Jones KA, VanLeeuwen JE, Woolfrey KM. Dendritic spine pathology in neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:285–93. doi: 10.1038/nn.2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meuer K, Suppanz IE, Lingor P, Planchamp V, Göricke B, Fichtner L, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 is an upstream regulator of mitochondrial fission during neuronal apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:651–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cartoni R, Martinou JC. Role of mitofusin 2 mutations in the physiopathology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A. Exp Neurol. 2009;218:268–73. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lawson VH, Graham BV, Flanigan KM. Clinical and electrophysiologic features of CMT2A with mutations in the mitofusin 2 gene. Neurology. 2005;65:197–204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000168898.76071.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Züchner S, Mersiyanova IV, Muglia M, Bissar-Tadmouri N, Rochelle J, Dadali EL, et al. Mutations in the mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A. Nat Genet. 2004;36:449–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alexander C, Votruba M, Pesch UE, Thiselton DL, Mayer S, Moore A, et al. OPA1, encoding a dynamin-related GTPase, is mutated in autosomal dominant optic atrophy linked to chromosome 3q28. Nat Genet. 2000;26:211–5. doi: 10.1038/79944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delettre C, Lenaers G, Griffoin JM, Gigarel N, Lorenzo C, Belenguer P, et al. Nuclear gene OPA1, encoding a mitochondrial dynamin-related protein, is mutated in dominant optic atrophy. Nat Genet. 2000;26:207–10. doi: 10.1038/79936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olichon A, Guillou E, Delettre C, Landes T, Arnaune-Pelloquin L, Emorine LJ, et al. Mitochondrial dynamics and disease, OPA1. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006; 1763:500-509. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Waterham HR, Koster J, van Roermund CW, Mooyer PA, Wanders RJ, Leonard JV. A lethal defect of mitochondrial and peroxisomal fission. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1736–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang X, Su B, Lee HG, Li X, Perry G, Smith MA, et al. Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9090–103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Su SC, Tsai LH. Cyclin-dependent kinases in brain development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:465–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Patrick GN, Zukerberg L, Nikolic M, de la Monte S, Dikkes P, Tsai LH. Conversion of p35 to p25 deregulates Cdk5 activity and promotes neurodegeneration. Nature. 1999;402:615–22. doi: 10.1038/45159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paoletti P, Vila I, Rifé M, Lizcano JM, Alberch J, Ginés S. Dopaminergic and glutamatergic signaling crosstalk in Huntington’s disease neurodegeneration: the role of p25/cyclin-dependent kinase 5. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10090–101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3237-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmidt HHW, Kelm M. Determination of nitrite and nitrate by the Griess reaction. In: Feelisch M, Stamler JS, eds. Methods in Nitric Oxide Research New York, NY John Wiley and Sons 1996:491-497. [Google Scholar]