Abstract

Cytokines and other peptides are secreted from skeletal muscles in response to exercise and function as hormones either locally within the muscle or by targeting distant organs. Such proteins are recognized as myokines, with the prototype myokine being IL-6. Several studies have established a role of these muscle-derived factors as important contributors of the beneficial effects of exercise, and the myokines are central to our understanding of the cross talk during and after exercise between skeletal muscles and other organs. In a study into the mechanisms of a newly defined myokine, CXCL-1, we found that CXCL-1 overexpression increases muscular fatty acid oxidation with concomitant attenuation of diet-induced fat accumulation in the adipose tissue. Clearly this study adds to the concept of myokines playing an important role in mediating the whole-body adaptive effects of exercise through the regulation of skeletal muscle metabolism. Yet, myokines also contribute to whole-body metabolism by directly signaling to distant organs, regulating metabolic processes in liver and adipose tissue. Thus accumulating data shows that myokines play an important role in restoring a healthy cellular environment, reducing low-grade inflammation and thereby preventing metabolic related diseases like insulin resistance and cancer.

Keywords: cancer, diabetes, exercise, myokine, physical activity

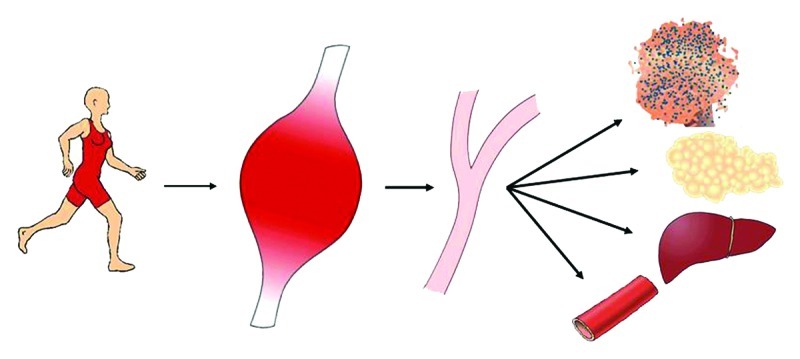

Exercise is associated with many beneficial metabolic and health effects. Today it is known that during exercise, cytokines and other peptides are secreted by the working muscles with the potential to act locally within the muscle tissue or in an endocrine manner by targeting distant organs. Although they are not exclusively secreted by the muscle cells, such proteins are classified as “myokines” within the context of skeletal muscle physiology.1 Emerging evidence suggests that these muscle-derived cytokines play an important role in mediating both acute exercise-associated metabolic changes, as well as the metabolic changes following training adaptation.2 Increased insulin responsiveness, glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation within skeletal muscles are some of the anticipated beneficial effects of regular exercise, all of which have been shown in part to be mediated by myokines. Likewise, systemic effects of myokines released in response to muscle contractions are involved in various immediate and long-term metabolic regulatory mechanisms in distant organs like the adipose tissue.3 Thus myokines are central to our understanding of the cross talk during and after exercise between skeletal muscles and other organs (Fig. 1). In view of that, further insight into the effect and regulation of potential myokines is of major importance.

Figure 1. Muscle-organ cross talk mediated by myokines. In response to muscle contraction skeletal muscle expresses and releases myokines into the circulation. The myokines mediate effects locally within the muscle in an autocrine or paracrine manner to increase glucose uptake and fat oxidation. When released into the circulation, the myokines act in a hormone-like fashion mediating peripheral effects including increased hepatic glucose production during exercise, lipolysis in adipose tissue and likely have a preventing effect on tumor growth.

The first myokine identified was interleukin 6 (IL-6),4 which is now recognized as the prototype myokine, exerting both local muscular effects as well as endocrine effects on distant organs.5 Since the discovery of IL-6, it has been recognized that skeletal muscle has the capacity to express a large range of myokines. Today the list of verified myokines includes IL-6, IL-8, IL-15, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) and follistatin-like-1.3 In addition, recent proteomic studies have predicted that the list of myokines may include more than 600 candidates belonging to distinctly different protein families.6 Recently we and others reported that an acute bout of exercise in mice induced a 6-fold increase in skeletal muscle mRNA and a 2.4-fold increase in serum concentration of the chemokine CXC motif ligand-1 (CXCL-1) also known as KC (keratinocyte-derived chemokine), suggesting that CXCL-1 acts as an exercise-induced myokine.7,8 Murine CXCL-1 is often mentioned as the functional homolog to human IL-8, which previously was identified as a myokine in humans.9 However, murine CXCL-1 shares the highest sequence homology (90% homology in conserved regions) with human CXCL-1, also named GROα (growth-related oncogene, α).10 CXCL-1 belongs to the glutamate-leucine-arginine (ELR)-containing CXC chemokine family and has primarily received attention for its role in inflammation, chemotaxis and angiogenesis,11,12 its neuro-protective effects13 and as a regulator of tumor growth14,15 whereas its role in metabolism remains to be clarified.

In line with the involvement of myokines in regulation of skeletal muscle metabolism, we went on to characterize the role of CXCL-1 in the exercise-associated adaptations in oxidative capacity in the muscle.16 To this end, we used a mouse model of in vivo electrotransfer-mediated overexpression of CXCL-1 in the tibialis cranialis muscle. The resulting increases in muscle CXCL-1 mRNA and serum CXCL-1 in this model are within the normo-physiological range and comparable to levels observed in response to a single bout of exercise.7,8 Importantly this model reflects the long-term effects of regular exercise-induced peaks in CXCL-1 rather than an occasional acute exercise effect. As assessed by MR scanning, DEXA scanning and weight of dissected organs, this long-term overexpression model revealed a CXCL-1-dependent reduction in the diet-induced fat accumulation in adipose tissue. In fact, after three months of high-fat feeding, CXCL-1 transfected animals had a significantly lower visceral fat mass (1277.5 ± 107.2 mg) compared with control mice (1889.5 ± 147.1 mg, p < 0.01). Likewise, did these mice have lower subcutaneous fat mass (494.8 ± 51.2 mg) compared with control mice (637.2 ± 40.8 mg, p < 0.05). Chow-fed mice also had lower levels of adipose tissue. As determined by DEXA scanning eight weeks after the transfection, the CXCL-1 transfected mice had significantly lower proportion of total body fat (13.2 ± 1.6%) compared with chow-fed control mice (19.8 ± 1.5%, p < 0.01). Similar results were found by MR scanning. Interestingly, the reduced accumulation of fat in the CXCL-1 transfected animals was associated with increased fatty acid oxidation in the muscles, as measured both directly and indirectly through upregulation of rate-limiting oxidative enzymes. Furthermore, the CXCL-1-dependent reduction adipose tissue mass was accompanied by whole-body improvements in glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. Clearly this study shows that by influencing metabolism locally in the muscles, the myokines are likely to be involved in the whole-body metabolic adaptive changes that occur in response to regular exercise like, for example, attenuation of fat accumulation.

Induction of other myokines, in particular IL-6, has been involved in similar metabolic adaptations. By signaling through the gp130Rβ/IL-6Rα receptor, causing subsequent activation of the AMPK and/or phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) pathways, IL-6 acts within the muscle to increase glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation.1 Upon receptor activation, IL-6 signals through either the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway or a Ras/ERK/CAAT enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) β pathway.17

In addition to the local muscular effects that indirectly affect whole body metabolism, myokines have also been shown to act directly on distant organs when released into the systemic circulation. Again IL-6 can be used as an example. Following release from both type I and type II muscle fibers in response to muscle contractions circulating IL-6 works in an endocrine fashion.1 In adipose tissue IL-6 has been shown to increase lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation,18 likely through the induction of AMPK phosphorylation.19 In further support of IL-6 affecting accumulation of fat in adipose tissue, IL-6 knockout mice have been found to develop late-onset obesity.20 In the liver, muscle-derived IL-6 is suggested to enhance hepatic glucose production during exercise21 and has been reported to directly upregulate gluconeogenic genes, i.e., phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and 6-phosphatase (G6Pase), leading to increased hepatic glucose production.22 Interestingly, IL-6 is also thought to affect pancreatic function, and secretory products from skeletal muscles have directly been shown to increase proliferation and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from primary β-cells.23,24 In addition, injection of IL-6 as well as elevated levels of IL-6 induced by exercise have recently been demonstrated to stimulate GLP-1 secretion from intestinal L cells and pancreatic α cells, leading to improvements in insulin secretion and glycemia.25 Thus, skeletal muscle and the pancreas act in a synergistic manner to monitor systemic glucose homeostasis and these results demonstrate a role of myokines in mediating cross talk between insulin sensitive tissues.

In line with this, plasma IL-6 is not only directly correlated with exercise intensity, but is also inversely related to plasma glucose level.26 With this, it is thought that IL-6 works as a sensor of carbohydrate availability.18,22,27 Thus, contracting muscle fibers produce and release IL-6 in an endocrine manner to facilitate substrate mobilization from liver and adipose tissue. More recently it was also reported that muscle-derived IL-6 induces expression of CXCL-1 in the liver and that IL-6 is directly essential for the peaks in liver CXCL-1 expression that occurs in response to exercise. These observations further suggest that IL-6 is involved in muscle-to-liver cross talk during exercise.8 Also, an exercise-induced and PGC1-a (transcriptional co-activator PPAR-γ co-activator-1 α) dependent myokine named Irisin was recently reported to replicate some of the positive effects of exercise and diet. It increases energy expenditure likely through stimulation of UCP-1 and brown-fat-like development and was found to improve glucose tolerance in obese animals.28

Definitely the communication network between muscles and other tissues define a physiological concept of muscle-to-organ cross talk. Common for many of the identified myokines are a direct or indirect effect on adipose tissue. Importantly, visceral fat is known as a source of systemic chronic low-grade inflammation, which in turn is involved in the pathogenesis of various disorders like insulin resistance, atherosclerosis and cancer.5 The attenuating effect of myokines on accumulation visceral adipose tissue either by acting directly on the adipose tissue itself or by improving fatty acid metabolism in the muscle is therefore of major importance in describing why inactivity is a strong risk factor for development of various diseases induced by low-grade inflammation like type 2 diabetes and cancer.5 With this, the myokines could in theory be therapeutic for human metabolic disease and other kind of disorders that normally are improved with regular exercise.

In continuation of this, regular exercise is clearly associated with reduced cancer development and progression in large epidemiological studies29,30 and a few animal studies report that exercise is associated with decreased tumor growth and metastatic dissemination.31 The protective effect of exercise is applicable on a diverse array of neoplastic diseases, indicating that the mechanism behind this protection is not limited by specific oncogenic mutations but likely caused by more general mechanisms. We have recently shown that myokines, in addition to the reduction of low-grade inflammation, also play a direct role in the tumor-suppressing effect of exercise. By incubating breast cancer cells with serum taken immediately after an exercise bout, we found that the exercise-conditioned serum could reduce cancer cell viability and induce apoptosis through caspase activation.32 This study identified Oncostatin M as an exercise-induced myokine with anti-proliferative effects on the breast cancer cells. Likely the protection of exercise on tumor development and progression occurs through a variety of exercise-related changes like improved inflammatory fitness, immune function, growth factor signaling, sex hormones and improved metabolic status some of which are affected by the myokines. Knowing the mechanisms behind the beneficial anti-cancer effect of exercise will serve as foundation for public health guide with regard to exercise and likely facilitate the improvement of current anti-cancer strategies

Taken together, with the identified pleiotropic effects of myokines on multiple tissues, leading to fine-tuning of fuel utilization and energy homeostasis in these tissues, we believe that these secreted myokines are able to restore a healthy cellular environment, reduce low-grade inflammation and thereby prevent metabolic related diseases like insulin resistance and cancer.

Acknowledgments

The Centre of Inflammation and Metabolism (CIM) is supported by a grant from the Danish National Research Foundation (02-512-55). This study was further supported by the Danish Medical Research Council, the Commission of the European Communities (grant agreement 223576-MYOAGE) and by grant from The Novo Scholarship Program 2010.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/adipocyte/article/20344

Reference

- 1.Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscle as an endocrine organ: focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1379–406. doi: 10.1152/physrev.90100.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedersen BK, Akerström TC, Nielsen AR, Fischer CP. Role of myokines in exercise and metabolism. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1093–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00080.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt C, Pedersen BK. The role of exercise-induced myokines in muscle homeostasis and the defense against chronic diseases. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:520258. doi: 10.1155/2010/520258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steensberg A, van Hall G, Osada T, Sacchetti M, Saltin B, Klarlund Pedersen B. Production of interleukin-6 in contracting human skeletal muscles can account for the exercise-induced increase in plasma interleukin-6. J Physiol. 2000;529:237–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedersen BK. Muscles and their myokines. J Exp Biol. 2011;214:337–46. doi: 10.1242/jeb.048074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henningsen J, Rigbolt KT, Blagoev B, Pedersen BK, Kratchmarova I. Dynamics of the skeletal muscle secretome during myoblast differentiation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2482–96. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.002113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nedachi T, Fujita H, Kanzaki M. Contractile C2C12 myotube model for studying exercise-inducible responses in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E1191–204. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90280.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen L, Pilegaard H, Hansen J, Brandt C, Adser H, Hidalgo J, et al. Exercise-induced liver chemokine CXCL-1 expression is linked to muscle-derived interleukin-6 expression. J Physiol. 2011;589:1409–20. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.200733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubio N, Sanz-Rodriguez F. Induction of the CXCL1 (KC) chemokine in mouse astrocytes by infection with the murine encephalomyelitis virus of Theiler. Virology. 2007;358:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oquendo P, Alberta J, Wen DZ, Graycar JL, Derynck R, Stiles CD. The platelet-derived growth factor-inducible KC gene encodes a secretory protein related to platelet alpha-granule proteins. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4133–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lira SA, Zalamea P, Heinrich JN, Fuentes ME, Carrasco D, Lewin AC, et al. Expression of the chemokine N51/KC in the thymus and epidermis of transgenic mice results in marked infiltration of a single class of inflammatory cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2039–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scapini P, Morini M, Tecchio C, Minghelli S, Di Carlo E, Tanghetti E, et al. CXCL1/macrophage inflammatory protein-2-induced angiogenesis in vivo is mediated by neutrophil-derived vascular endothelial growth factor-A. J Immunol. 2004;172:5034–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.5034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parachikova A, Nichol KE, Cotman CW. Short-term exercise in aged Tg2576 mice alters neuroinflammation and improves cognition. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:121–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhawan P, Richmond A. Role of CXCL1 in tumorigenesis of melanoma. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:9–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng G, Ohmori Y, Chang PL. Production of chemokine CXCL1/KC by okadaic acid through the nuclear factor-kappaB pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:43–52. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen L, Olsen CH, Pedersen BK, Hojman P. Muscle-derived expression of the chemokine CXCL1 attenuates diet-induced obesity and improves fatty acid oxidation in the muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E831–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00339.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamimura D, Ishihara K, Hirano T. IL-6 signal transduction and its physiological roles: the signal orchestration model. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;149:1–38. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Hall G, Steensberg A, Sacchetti M, Fischer C, Keller C, Schjerling P, et al. Interleukin-6 stimulates lipolysis and fat oxidation in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3005–10. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly M, Keller C, Avilucea PR, Keller P, Luo Z, Xiang X, et al. AMPK activity is diminished in tissues of IL-6 knockout mice: the effect of exercise. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:449–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallenius V, Wallenius K, Ahrén B, Rudling M, Carlsten H, Dickson SL, et al. Interleukin-6-deficient mice develop mature-onset obesity. Nat Med. 2002;8:75–9. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Febbraio MA, Hiscock N, Sacchetti M, Fischer CP, Pedersen BK. Interleukin-6 is a novel factor mediating glucose homeostasis during skeletal muscle contraction. Diabetes. 2004;53:1643–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banzet S, Koulmann N, Simler N, Sanchez H, Chapot R, Serrurier B, et al. Control of gluconeogenic genes during intense/prolonged exercise: hormone-independent effect of muscle-derived IL-6 on hepatic tissue and PEPCK mRNA. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:1830–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00739.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouzakri K, Plomgaard P, Berney T, Donath MY, Pedersen BK, Halban PA. Bimodal effect on pancreatic β-cells of secretory products from normal or insulin-resistant human skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2011;60:1111–21. doi: 10.2337/db10-1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gopurappilly R, Bhonde R. Can multiple intramuscular injections of mesenchymal stromal cells overcome insulin resistance offering an alternative mode of cell therapy for type 2 diabetes? Med Hypotheses. 2012;78:393–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellingsgaard H, Hauselmann I, Schuler B, Habib AM, Baggio LL, Meier DT, et al. Interleukin-6 enhances insulin secretion by increasing glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from L cells and alpha cells. Nat Med. 2011;17:1481–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nehlsen-Cannarella SL, Fagoaga OR, Nieman DC, Henson DA, Butterworth DE, Schmitt RL, et al. Carbohydrate and the cytokine response to 2.5 h of running. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:1662–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.5.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen BK, Steensberg A, Fischer C, Keller C, Keller P, Plomgaard P, et al. Searching for the exercise factor: is IL-6 a candidate? J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2003;24:113–9. doi: 10.1023/A:1026070911202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boström P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, Korde A, Ye L, Lo JC, et al. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. 2012;481:463–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedenreich CM, Orenstein MR. Physical activity and cancer prevention: etiologic evidence and biological mechanisms. J Nutr. 2002;132(Suppl):3456S–64S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.11.3456S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holick CN, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Titus-Ernstoff L, Bersch AJ, Stampfer MJ, et al. Physical activity and survival after diagnosis of invasive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:379–86. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones LW, Viglianti BL, Tashjian JA, Kothadia SM, Keir ST, Freedland SJ, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on tumor physiology in an animal model of human breast cancer. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:343–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00424.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hojman P, Dethlefsen C, Brandt C, Hansen J, Pedersen L, Pedersen BK. Exercise-induced muscle-derived cytokines inhibit mammary cancer cell growth. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E504–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00520.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]