Abstract

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), a member of the prion diseases, is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder suspected to be caused by a malfunction of prion protein (PrP). Although BSE prions have been reported to be transmitted to a wide range of animal species, dogs and hamsters are known to be BSE-resistant animals. Analysis of canine and hamster PrP could elucidate the molecular mechanisms supporting the species barriers to BSE prion transmission. The structural stability of 6 mammalian PrPs, including human, cattle, mouse, hamster, dog and cat, was analyzed. We then evaluated intramolecular interactions in PrP by fragment molecular orbital (FMO) calculations. Despite similar backbone structures, the PrP side-chain orientations differed among the animal species examined. The pair interaction energies between secondary structural elements in the PrPs varied considerably, indicating that the local structural stabilities of PrP varied among the different animal species. Principal component analysis (PCA) demonstrated that different local structural stability exists in bovine PrP compared with the PrP of other animal species examined. The results of the present study suggest that differences in local structural stabilities between canine and bovine PrP link diversity in susceptibility to BSE prion infection.

Keywords: prion, BSE, species barrier, FMO, structure

Introduction

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), a member of the prion diseases, is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder caused by structural conversion of cellular prion protein (PrPC) into its pathogenic isoform (PrPSc).1 However, little is known about the mechanism of this conversion. The Prnp gene is highly conserved among many mammalian species and PrPC shows a high degree of homology among mammals, accounting for the ease of cross-species transmission of prion diseases. Several amino acids have been identified as critical for interspecies prion transmission; amino acid substitutions of these critical residues create a species barrier, resulting in diminishment or complete abolition of the efficiency of prion transmission.2

A wide range of host species are affected by BSE prions. Experimentally, BSE has been transmitted to mice,3 sheep, goats,4 minks,5 marmosets,6 macaques7 and lemurs.8 In nature, BSE has been transmitted to cattle,9 several zoo ruminants10 and domestic and wild cats.11 Furthermore, BSE has been transmitted to humans via cattle, causing variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD).12 On the other hand, several species have been observed to be resistant to BSE infection. Although, no experimental result was reported regarding BSE-challenged dog. While cats were reported to develop feline spongiform encephalopathy, dogs did not appear to be affected by BSE, even after they were fed similarly infected pet food.13 In addition, typical BSE prions were not transmitted to hamsters at primary passage.14 Analysis of canine and hamster PrPC could elucidate the molecular mechanisms accounting for the species barrier to BSE prion transmission in these species.

The three-dimensional structure of PrPSc cannot be determined directly because PrPSc is insoluble in aqueous solution and has a strong tendency to form fibrils and amorphous aggregates. It has reported that the negative charge of polyoxometalates determines the quaternary structure of PrPSc fibrils.15 However, little is currently known about the PrPSc structures. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography have revealed that the three-dimensional structure of the C-terminal globular domains of PrPC showed similarities among the various mammalian species examined.16-20 It has reported that β2–α2 loop has an important role in intermolecular interactions and it may be a key for PrP aggregation.21 Still, no critical conformational differences have been identified that are linked to species barriers to prion transmission. An alternate approach is necessary to reveal the structural differences and/or differences in structural stability of PrPC that exist among the different species.

The ab initio fragment molecular orbital (FMO) calculation is a powerful tool for quantum chemical analysis of intramolecular interactions in proteins and has been utilized to analyze protein-ligand binding affinities22,23 and protein stabilities.24-26 Intramolecular interactions between residues play a key role in the structural stability of proteins.27 The intra- and inter-molecular interactions of mouse PrP models with explicit water has been examined using the FMO-RIMP2 method.28 Using the FMO calculations, we previously demonstrated that the local structural stability of the E200K mutant of PrP was altered vis à vis that of the wild-type PrP. The instability of the E200K mutant structure is thought to be a trigger for conversion to PrPSc.24

In this study, we compared the intramolecular interactions of 6 mammalian PrPs ab initio to identify their structural differences, which were not detected by classical methods of structural determination. A clarification of the differences in intramolecular interactions between BSE-susceptible and BSE-resistant hosts may facilitate elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of species barriers to BSE prion transmission. Our calculations showed that canine and bovine PrP differ markedly in their local structural stabilities, providing a possible rationale for why canines and hamsters were resist to BSE infection.

Results

Structural comparison of PrP

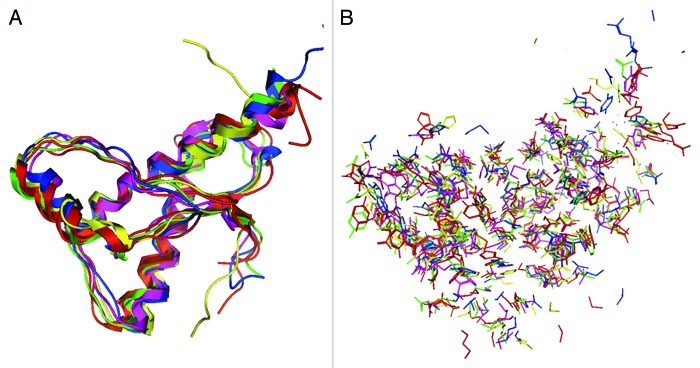

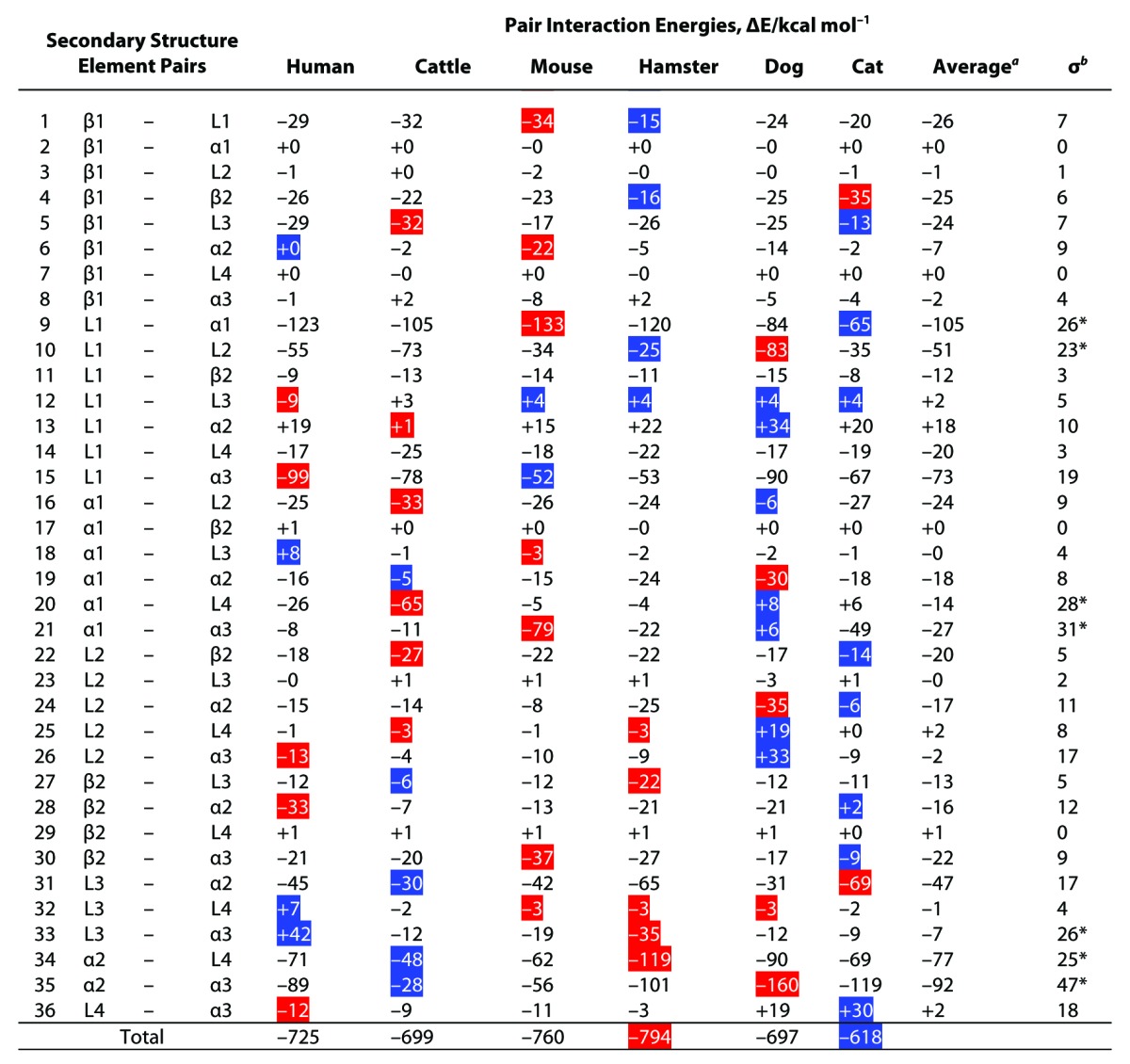

The NMR structures of 6 mammalian PrPs were compared. Their amino acid sequences and secondary structures are shown in Figure 1. As reported previously,16-20 the PrP backbone structures highly resemble one another (Fig. 2A). However, the orientation of PrP side chains is different, both on the outer surface and in the internal region (Fig. 2B), suggesting that the PrPs of all 6 animal species show differing intermolecular interactions and/or local structural stabilities.

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequences of C-terminal region of 6 mammalian prion proteins (PrPs). The 6 mammalian PrP sequences were compared. The bold residues are not conserved among the 6 PrPs. The residue numbering for all PrP was aligned with that for human PrP. The secondary structural element information was shown as α for α–helix, β for β–strand and L for loop or coil region.

Figure 2.

Superposition of the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structures of 6 mammalian PrPs. The structures of backbone (A) and side chains (B) are illustrated: human (red), bovine (green), mouse (blue), hamster (purple), dog (yellow) and cat (orange).

FMO analysis of intramolecular interactions of PrP

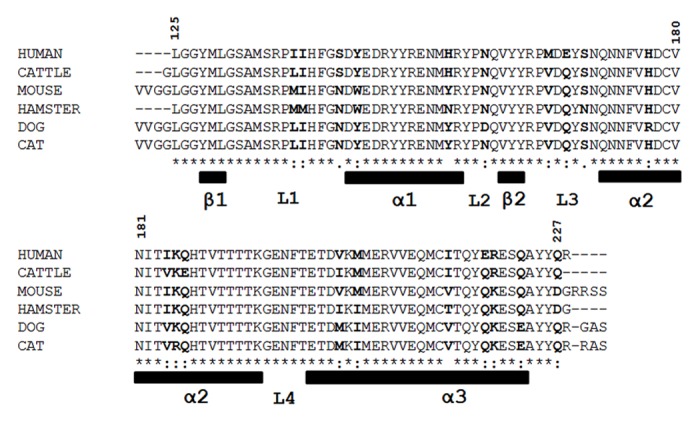

To assess the intramolecular interactions of PrP, an FMO calculation was performed. The values of internal interaction energies (∆EInt) of 9 secondary structural elements were negative, indicating the absence of clear differences among the animal species (Table S1). The values of the interfragment interaction energies (IFIEs) of residue pairs were negative or positive, denoting that the pairs were structurally stable or unstable, respectively. Since ∆EInt is generated by summation of all of the IFIEs between the residues belonging to same element, this result suggests that each secondary element is structurally stable and primarily contributes to the similarity in backbone structure among the species. To compare the intramolecular interaction between secondary structural elements, we calculated the energies of 36 pair interactions (Table 1). As with IFIE and ∆EInt, the pair interaction energy (∆EPair) values were negative or positive, denoting that the pairs were structurally stable or unstable, respectively. It should be noted here that the interaction energies of ∆EInt and ∆EPair provides information on local structural stabilities for the secondary structure elements of PrP but these energies are enthalpic contributions but not local folding free energies. Although partial unfolding free energies in some specified residues of PrP has been monitored by NMR,29 present technique could not be used to analyze denaturation status of local elements of PrP. Therefore, there are no experimental data for verifying the obtained FMO calculations. The total ∆EPair for all species combined was negative, with similar values ranging from -618 to -794 kcal/mol. This result also suggests that the global structure for all PrPs is stable, irrespective of the animal species from which it originates. A maximum and a minimum value of ΔEPair within each examined animal species is shown in blue and red, respectively, in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, the ΔEPair values substantially differed between species on an individual basis. The 7 elemental pairs, L1-α1, L1-L2, α1-L4, α1-α3, L3-α3, α2-L4 and α2-α3, showed substantially variability in their interaction energies among the animal species (σ > 20 kcal/mol; Table 1). Under mildly acidic pH conditions, the values of the 2 pairs (L1-α3 and α1-α2) also varied substantially (Table S2). These results indicate that the intramolecular interaction networks, specifically, the local structural stabilities, differed considerably among PrP species, despite their similarities in backbone structure. Notably, these differences were primarily caused by differences in minor amino acid residues and/or in structural orientations of side chains.

Table 1. The pair interaction energies (ΔEPair) of 6 mammalian PrP models under neutral pH condition.

The pair interaction energies were evaluated by summation of the calculated IFIEs between the residues on the element pairs. aThe average for the values of ΔEPair. bThe standard deviations σ for the values of the ΔEPair. *The varied ΔEPair among the 6 mammalian PrPC; σ ≥ 20 kcal/mol. The blue-marked boxes are the maximum values (i.e., most repulsive interaction) among the PrP species. The red-marked boxes are the minimum values (i.e., most attractive interaction) among the PrP species.

The interaction between α1 and α2 of BSE-susceptible animals (human, bovine, mouse and cat) ranged from -5 to -18 kcal/mol, whereas that of BSE-resistant animals was -24 kcal/mol (for hamster) and -30 kcal/mol (for dog). Similarly, the interaction between α2 and L4 of BSE-susceptible animals ranged from -48 to -71 kcal/mol and that of BSE-resistant animals was -90 kcal/mol (for dog) and -119 kcal/mol (for hamster). These results indicate that PrP from BSE-resistant animals maintains a relatively stable interaction in α1-α2 and α2-L4 regions (Table 1).

PCA for pair interaction energies (ΔEPair) of PrP

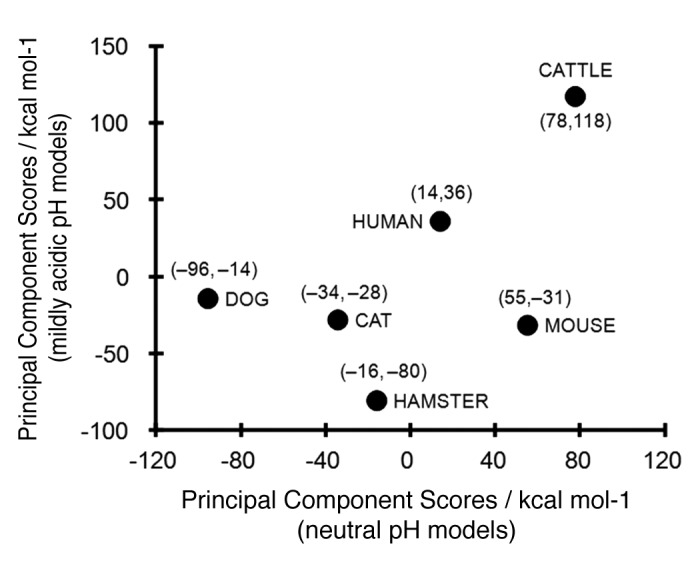

Principal component analysis (PCA) for the ∆EPair of animal PrP models under neutral and mildly acidic pH conditions was performed to clearly elucidate differences in ∆EPair values among animal PrPs. The coefficients of the eigenvector for the first principal component showed that ∆EPair differences were primarily attributable to 4 elemental pairs under neutral pH conditions: L1-α1, α1-L4, α2-L4 and α2-α3; and 6 element pairs under mildly acidic pH conditions L1-α1, L1-L2, α1-α2, α1-L4, α2-L4 and α2-α3 (Table S2). Figure 3 shows the first principal component scores of the ΔEPair for the 6 animal PrPs in neutral and mildly acidic pH conditions. The PCA demonstrated that bovine and canine PrPs show markedly different local structural stabilities under neutral pH conditions. The interaction of the α2-α3 pair is significantly weaker in bovine PrP than in PrP of other animals and this difference may explain the peculiar interaction observed in bovine PrP (Fig. 3) and this pair energy might be one of the most important factor regarding the BSE sensitivity. The PCA score of the hamster PrP was plotted at a great distance from bovine PrP under mildly acidic pH conditions (Fig. 3). Higher principal components in the PCA did not identify any additional useful relationships (data not shown).

Figure 3.

First principal component scores in the principal component analysis (PCA) for the ΔEPair of mammalian PrP. The scores under neutral (pH 7.0) and mildly acidic (pH 4.5) models were plotted in axes of abscissas and ordinates, respectively. The numerical values in the parenthesis are the scores for neutral pH and mildly acidic pH models, respectively.

Discussion

During the transfer of prions from one species to another, complete failure of transmission or a greatly extended incubation period of affected animals is often encountered. Although the precise mechanisms of this species barrier phenomenon have not been fully elucidated, it is likely to have a biophysical basis in the structural differences between host PrPC and PrPSc in the inoculum.1 The conversion from PrPC to PrPSc may be performed in multiple steps; a heterodimer of PrPC and PrPSc has been purported to be generated initially.1 A comparison of structural determinations of PrPs from different species may provide an insight into the susceptibility of a given species to interspecies prion transmission and into the nature of the species barrier.30

Although BSE prions have reportedly been transmitted to a wide range of animal species, dogs are known to be BSE-resistant animals.13 It has also been reported that typical BSE was not transmitted to hamsters at the primary passage.14 However, an atypical form of BSE known as the L-type BSE, was transmitted to hamsters at the primary passage.31 This may imply that the resistance in hamsters to BSE prion infection is not absolute or even specific for typical BSE prions. We attempted to compare the structural differences among 6 mammalian PrPs based on their typical BSE susceptibility: 4 BSE-susceptible animals (cattle, cats, mice and humans) and 2 BSE-resistant animals (dogs and hamsters).

In this study, we demonstrated that the side-chain orientations of the PrP structures were species specific, irrespective of their similar backbone structures (Fig. 2). The geometrical differences in side-chain orientations in PrP caused by point mutations29,32 or amino acid substitutions17 have been investigated. These geometrical changes may affect critical intramolecular interactions in PrP. A quantitative evaluation of intramolecular interactions is essential in order to elucidate differences in PrP structural stability.

We compared the local structural stabilities of the secondary structural elements of mammalian PrP by FMO calculations. The structural stabilities of the elements were similar among all mammalian species (Table S1). However, our calculations show a considerably wide range of ΔEPair values in the specific local pairs and it indicates that the local structural stabilities varied among different animal species (Table 1). Since the magnitude of ΔEPair is indicative of the strength of the interaction, a negative value of ΔEPair denotes an attractive interaction (i.e., a structurally stable conformation), whereas a positive value denotes a repulsive interaction (i.e., a structurally unstable conformation). The stable pair regions are expected to be less susceptible to denaturation of structural conformation. These local regions could possess a highly variable internal local protein dynamics properties among the different animal species.

It is believed that the endosomes of scrapie-infected cells, characterized by mildly acidic pH conditions (pH 4.0–6.0), are the sites of PrPSc accumulation, while the cell surface, characterized by neutral pH conditions (~pH 7), is the site of PrPC binding to PrPSc.33 It has also reported that the endosomal recycling compartment is thought as the site of prion conversion.34 Our calculations revealed that the local structural stabilities denoted by ΔEPair in the specific regions are markedly altered under lower pH conditions, an observation that highly depended on the animal species examined (Table 1; and Table S2). Local structural stability of PrP varied with changes in pH conditions and no similarities among animal species were observed in association with pH alteration. This suggests that PrPSc conversion mechanisms differ depending on the animal species.

Our calculations also demonstrated that the total structural stabilities of the PrPs in different species were not directly related to their BSE susceptibilities and/or resistance, suggesting a greater importance for local structure of PrP in the elucidation of PrP denaturation properties. To clarify this difference among animal species, we performed a PCA. The analysis clearly demonstrated that different structural stabilities exist between dog and cattle under neutral conditions and between hamster and cattle under mildly acidic conditions (Fig. 3). This observation suggests that different mechanisms underlie the resistance to BSE infection between dog and hamster. Our analysis showed that bovine PrP possessed markedly different characteristics from other PrPs, consistent with a previous observation that bovine PrP is more highly resistant to urea denaturation than are PrPs of other species.29

The peculiar local structural stabilities of bovine PrP was primarily derived by the weaker stability of the α2-α3 interaction. Furthermore, relatively weak interactions of α1-α2 and α2-L4 were observed in BSE-susceptible animals. These results may be explained by the hypothesis that PrP with weak interactions among α1, α2 and α3 sites could be converted to PrPSc by BSE prion infection. This may also account for the observation that resistance against proteolysis of PrPSc from BSE was weaker than that against scrapie.35

In conclusion, our FMO calculations revealed the different structural stabilities of PrP among different animal species. Cattle PrP has different biophysical characteristics from other mammalian PrPs. The results of this study suggest that differences in local structural stabilities of α1–α2 and α2–L4 of PrP provide a link to the mechanisms of species barriers against BSE prion infection.

Materials and Methods

Structural modeling of PrPs for FMO calculations

Initial atomic coordinates of mammalian PrP for human, cattle, mouse, hamster, dog and cat were extracted from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) structures with the codes 1QM3, 1DWZ, 1XYX, 1B10, 1XYK and 1XYJ, respectively. The residue numbering for all PrP species was identical to that of human PrP. The secondary structures of PrP were defined as follows: 3 α-helices (α1: 144–156, α2: 172–194 and α3: 200–223), 2 β-strands (β1: 129–131 and β2: 161–163) and 4 loop regions (L1: 132–143, L2: 157–160, L3: 164–171 and L4: 195–199) (Fig. S1). A multiple sequence alignment for the 6 PrPs was carried out using ClustalW (1.8.3 WWW Server in DNA Data Bank of Japan, National Institute of Genetics)36 (Fig. 1). The PrP structural models were constructed for the top 5 conformers deposited in the PDB. For the neutral pH (pH 7.0) model of the PrPs as a cell surface model,24 we made the following assumptions: (1) lysine, arginine and the N–terminal residues were positively charged; (2) glutamic acid, aspartic acid and the C-terminal residues were negatively charged; and (3) histidines were neutrally protonated at the Nτ atom. All other residues were considered to be neutrally charged. In the mildly acidic (pH 4.5) condition, the protonation states were identical to the pH 7.0, with the exception of histidines, in which the side chains were imidazolium forms and thus positively charged. The proteins in explicit water were modeled by arranging water molecules in a sphere within 16 Å of the protein surface. The geometric optimizations for protein models in water were performed using an AMBER99 force field with constraints of fixed heavy atoms in the whole protein, followed by restricting of the water molecules within 8 Å on the protein (1489–1913 molecules) for FMO calculations. Examples of solvated models are shown in Figure S2. The generated models were further optimized under constraints of fixed heavy atoms, with the exceptions of N- and C-terminal residues of the proteins. The modeling procedures were performed using MOE (version 2011.10, Chemical Computing Group Inc.).

FMO calculations

Ab initio FMO calculations were carried out using the ABINIT-MP software (Advance/BioStation ver. 3.3, Advance Soft Corp.) with the RI-MP2 method37,38 combined with the 6-31G basis set. In the FMO calculation, the protein models were fragmented into single amino acid residues, with the exception of the disulfide-bond residues of Cys176 and Cys214, which were considered a single fragment. The interfragment interaction energy (IFIE) between covalently adjoining residues were evaluated by subtracting the calculated IFIE from an IFIE between methyl groups in an ethylene molecule with a gauche form; this form has an identical C-C bond length with a bond length between a Cα atom and a backbone carbonyl C atom in the residues of the protein structure.39 An average of the IFIEs was calculated for the top 5 conformer models. The pair interaction energy  between the elements P and Q was evaluated using the following equation:

between the elements P and Q was evaluated using the following equation:

| (1) |

where the ΔEIJ is the IFIE between the I and J fragments in the P and Q elements, respectively. The internal interaction energy  for the element P was calculated using the following equation:

for the element P was calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

The IFIE for the disulfide bond fragment was considered in the  and

and  , as described previously.22 A typical run of a PrP model with explicit water took a calculation time of 10 hours on average using four quad-core AMD Opteron 2.5 GHz cluster (16 CPUs).

, as described previously.22 A typical run of a PrP model with explicit water took a calculation time of 10 hours on average using four quad-core AMD Opteron 2.5 GHz cluster (16 CPUs).

PCA

The PCA for the ΔEPair was performed by solving an eigenvalue problem for an actual variance-covariance matrix built from the variances of ΔEPair. The PCA was carried out using the statistical functions in the Microsoft EXCEL package (Microsoft Corp.). The principal component score of each animal species for the first principal component was obtained by calculating an inner product of the eigenvector for the first principal component and the vector whose components were the values that were generated by subtracting averaged ΔEPair over all species from ΔEPair.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgements

The numerical calculations were supported by the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Research Technology Center (AFFRIT). We thank Reiko Takeuchi for her general assistance. This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the BSE and other Prion Disease Control Projects of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Japan.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BSE

bovine spongiform encephalopathy

- FMO

fragment molecular orbital

- IFIE

interfragment interaction energy

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- EInt

internal interaction energy

- Epair

pair interaction energy

- PCA

principal component analysis

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- PrP

prion protein

- PrPC

cellular PrP

- PrPSc

pathogenic isoform of PrP

- vCJD

variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/prion/article/23122

References

- 1.Prusiner SB. Molecular biology of prion diseases. Science. 1991;252:1515–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1675487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore RA, Vorberg I, Priola SA. Species barriers in prion diseases--brief review. Arch Virol Suppl. 2005;19:187–202. doi: 10.1007/3-211-29981-5_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraser H, Bruce ME, Chree A, McConnell I, Wells GA. Transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy and scrapie to mice. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1891–7. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-8-1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster JD, Hope J, Fraser H. Transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy to sheep and goats. Vet Rec. 1993;133:339–41. doi: 10.1136/vr.133.14.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson MM, Hadlow WJ, Huff TP, Wells GA, Dawson M, Marsh RF, et al. Experimental infection of mink with bovine spongiform encephalopathy. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2151–5. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-9-2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker HF, Ridley RM, Wells GA, Ironside JW. Prion protein immunohistochemical staining in the brains of monkeys with transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1998;24:476–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1998.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasmézas CI, Deslys JP, Demaimay R, Adjou KT, Lamoury F, Dormont D, et al. BSE transmission to macaques. Nature. 1996;381:743–4. doi: 10.1038/381743a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bons N, Mestre-Frances N, Belli P, Cathala F, Gajdusek DC, Brown P. Natural and experimental oral infection of nonhuman primates by bovine spongiform encephalopathy agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4046–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells GAH, Wilesmith JW. The neuropathology and epidemiology of bovine spongiform encephalopathy. Brain Pathol. 1995;5:91–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1995.tb00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkwood JK, Cunningham AA. Epidemiological observations on spongiform encephalopathies in captive wild animals in the British Isles. Vet Rec. 1994;135:296–303. doi: 10.1136/vr.135.13.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewicker-Trautwein M, Bradley R. Portrait of transmissible feline spongiform encephalopathy. In: Hӧrnlimann B, Riesner D, Kretzschmar H, eds. Prions in humans and animals. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter 2006:271-4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collinge J, Sidle KC, Meads J, Ironside J, Hill AF. Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of ‘new variant’ CJD. Nature. 1996;383:685–90. doi: 10.1038/383685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirkwood JK, Cunningham AA. Epidemiological observations on spongiform encephalopathies in captive wild animals in the British Isles. Vet Rec. 1994;135:296–303. doi: 10.1136/vr.135.13.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokoyama T, Masujin K, Iwamaru Y, Imamura M, Mohri S. Alteration of the biological and biochemical characteristics of bovine spongiform encephalopathy prions during interspecies transmission in transgenic mice models. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:261–8. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.004754-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wille H, Shanmugam M, Murugesu M, Ollesch J, Stubbs G, Long JR, et al. Surface charge of polyoxometalates modulates polymerization of the scrapie prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3740–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812770106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zahn R, Liu A, Lührs T, Riek R, von Schroetter C, López García F, et al. NMR solution structure of the human prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:145–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gossert AD, Bonjour S, Lysek DA, Fiorito F, Wüthrich K. Prion protein NMR structures of elk and of mouse/elk hybrids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:646–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409008102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.López Garcia F, Zahn R, Riek R, Wüthrich K. NMR structure of the bovine prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8334–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lysek DA, Schorn C, Nivon LG, Esteve-Moya V, Christen B, Calzolai L, et al. Prion protein NMR structures of cats, dogs, pigs, and sheep. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:640–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408937102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu H, Farr-Jones S, Ulyanov NB, Llinas M, Marqusee S, Groth D, et al. Solution structure of Syrian hamster prion protein rPrP(90-231) Biochemistry. 1999;38:5362–77. doi: 10.1021/bi982878x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sigurdson CJ, Joshi-Barr S, Bett C, Winson O, Manco G, Schwarz P, et al. Spongiform encephalopathy in transgenic mice expressing a point mutation in the β2-α2 loop of the prion protein. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13840–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3504-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuzawa K, Mochizuki Y, Tanaka S, Kitaura K, Nakano T. Molecular interactions between estrogen receptor and its ligand studied by the ab initio fragment molecular orbital method. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:16102–10. doi: 10.1021/jp060770i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawada T, Hashimoto T, Nakano H, Suzuki T, Suzuki Y, Kawaoka Y, et al. Influenza viral hemagglutinin complicated shape is advantageous to its binding affinity for sialosaccharide receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;355:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasegawa K, Mohri S, Yokoyama T. Fragment molecular orbital calculations reveal that the E200K mutation markedly alters local structural stability in the human prion protein. Prion. 2010;4:38–44. doi: 10.4161/pri.4.1.10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishikawa T, Ishikura T, Kuwata K. Theoretical study of the prion protein based on the fragment molecular orbital method. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2594–601. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukuzawa K, Komeiji Y, Mochizuki Y, Kato A, Nakano T, Tanaka S. Intra- and intermolecular interactions between cyclic-AMP receptor protein and DNA: ab initio fragment molecular orbital study. J Comput Chem. 2006;27:948–60. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stites WE. Protein-Protein Interactions: Interface Structure, Binding Thermodynamics, and Mutational Analysis. Chem Rev. 1997;97:1233–50. doi: 10.1021/cr960387h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishikawa T, Kuwata K. Interaction analysis of the native structure of prion protein with quantum chemical calculations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2010;6:538–47. doi: 10.1021/ct900456v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Julien O, Chatterjee S, Bjorndahl TC, Sweeting B, Acharya S, Semenchenko V, et al. Relative and regional stabilities of the hamster, mouse, rabbit, and bovine prion proteins toward urea unfolding assessed by nuclear magnetic resonance and circular dichroism spectroscopies. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7536–45. doi: 10.1021/bi200731e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarzinger S, Willbold D, Ziegler J. Structural studies of prion proteins. In: Hӧrnlimann B, Riesner D, Kretzschmar H, eds. Prions in humans and animals. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter 2006:79-94. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shu YJ, Masujin K, Okada H, Iwamaru Y, Imamura M, Matsuura Y, et al. Characterization of Syrian hamster adapted prions derived from L-type and C-type bovine spongiform encephalopathies. Prion. 2011;5:103–8. doi: 10.4161/pri.5.2.15847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calzolai L, Lysek DA, Guntert P, von Schroetter C, Riek R, Zahn R, et al. NMR structures of three single-residue variants of the human prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8340–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borchelt DR, Taraboulos A, Prusiner SB. Evidence for synthesis of scrapie prion proteins in the endocytic pathway. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16188–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marijanovic Z, Caputo A, Campana V, Zurzolo C. Identification of an intracellular site of prion conversion. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000426. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuczius T, Groschup MH. Differences in proteinase K resistance and neuronal deposition of abnormal prion proteins characterize bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and scrapie strains. Mol Med. 1999;5:406–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ten-no S, Iwata S. Three-center expansion of electron repulsion integrals with linear combination of atomic electron distributions. Chem Phys Lett. 1995;240:578–84. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(95)00564-K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ten-no S, Iwata S. Multiconfiguration self‐consistent field procedure employing linear combination of atomic‐electron distributions. J Chem Phys. 1996;105:3604–11. doi: 10.1063/1.472231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fedorov DG, Kitaura K. Pair interaction energy decomposition analysis. J Comput Chem. 2007;28:222–37. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.