Abstract

The M-type receptor for phospholipase A2 (PLA2R1) is the major target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy (iMN). Our recent genome-wide association study showed that genetic variants in an HLA-DQA1 and phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R1) allele associate most significantly with biopsy-proven iMN, suggesting that rare genetic variants within the coding region of the PLA2R1 gene may contribute to antibody formation. Here, we sequenced PLA2R1 in a cohort of 95 white patients with biopsy-proven iMN and assessed all 30 exons of PLA2R1, including canonical (GT-AG) splice sites, by Sanger sequencing. Sixty patients had anti-PLA2R1 in serum or detectable PLA2R1 antigen in kidney tissue. We identified 18 sequence variants, comprising 2 not previously described, 7 reported as rare variants (<1%) in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database or the 1000 Genomes project, and 9 known to be common polymorphisms. Although we confirmed significant associations among 6 of the identified common variants and iMN, only 9 patients had the private or rare variants, and only 4 of these patients were among the 60 who were PLA2R positive. In conclusion, rare variants in the coding sequence of PLA2R1, including splice sites, are unlikely to explain the pathogenesis of iMN.

Idiopathic membranous nephropathy (iMN) is the leading cause of nephrotic syndrome in the adult white population. It is characterized by immune complex deposition in the subepithelial layer of the glomerular basement membrane. On the basis of studies in Heymann nephritis, a model of MN in the rat, it was suggested that immune complexes were formed locally, by the binding of antibodies to a podocytic antigen.1 The description of neonatal MN caused by maternal antibodies against neutral endopeptidase provided proof of concept.2 Further evidence was provided by the discovery of the M-type receptor for phospholipase A2 (PLA2R1) as the predominant autoantigen in iMN.3 It is well established that 70% of white patients with active disease have antibodies against PLA2R1.1,3,4 Although no studies have firmly proven that the antibodies are indeed pathogenic, genetics studies have supported the important role of PLA2R1 in the pathogenesis of iMN. Recently, we have shown highly significant associations to iMN with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located on chromosomes 6 and 2, by means of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in three independent cohorts.5 The region of interest defined on chromosome 2 includes the gene PLA2R1. SNPs in this gene have also been shown to be associated to iMN susceptibility in two candidate gene association studies performed in Korea and Taiwan.6,7 These findings together suggest an important role for PLA2R1 in the pathogenicity of iMN.

Our GWAS was based on common SNPs, as is typical for most GWAS. These SNPs serve as genetic markers used to identify alleles or haplotypes of interest. Of note, our GWAS study showed that both the HLA locus on chromosome 6 and the PLA2R1 locus on chromosome 2 were significantly associated with iMN not only on the SNP level (basic allele test) but also on the haplotype level (haplotype association test).5 These SNPs demarcate alleles that are different in cases versus controls. Not only common SNPs but also rare mutations can be the cause of a signal identified by GWAS.8 Although iMN is not a simple genetic disorder with classic Mendelian inheritance, the strong and significant association of this phenotype to PLA2R1 (and the HLA locus) leads to the hypothesis that rare genetic variants within the coding region of the PLA2R1 gene may explain antibody formation. In the current study, we performed sequencing of the coding regions of the PLA2R1 gene to confirm this hypothesis.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Ninety-five patients with biopsy-proven iMN were included: 48 from the French cohort and 47 from the Dutch cohort, respectively. Patients were mostly male (75%), and the mean age ± SD at diagnosis was 51±15 years. All patients were of self-reported white ancestry.

Serum samples were available for 82 patients; anti-PLA2R antibodies were present in 43 samples. In addition, 17 patients were considered positive according to the presence of PLA2R antigen in their kidney biopsy specimen (Supplemental Table S1).

Sequencing

All 30 exons, including essential splice sites (defined as the two intronic nucleotides—canonical GT and AG—at the intron-exon boundaries, respectively) were sequenced by Sanger technology. We identified 18 variants, including 3 in noncoding regions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sequence variants in PLA2R1 observed in the present study (95 patients with iMN)

| Chr | Position | Name | Ref | All | CEU AF | AF Patients | P Value | Ref cDNA | cDNA | Prot Level | Effect | Exon | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | 160803929 | rs181959329 | C | C/T | 0 | 0.005 | G | c.3850+1G>A | Ess | 26 | Donor ss | ||

| 2 | 160808075 | rs3828323b | C | C/T | 0.511 | 0.382 | 0.0016 | G | c.3316G>A | p.Gly1106Ser | Missense | 24 | Linker region between CTLD6 and CTLD7 |

| 2 | 160808076 | rs72954858 | G | G/A | 0.012 | 0.027 | 0.13 | C | c.3315C>T | p.His1105= | Synonymous | 24 | Linker region between CTLD6 and CTLD7 |

| 2 | 160833188 | rs2715918b | A | A/G | 0.821 | 0.716 | 0.0013 | T | c.2437+8T>C | Intron | 16 | ||

| 2c | 160840562 | Novel | A | A/G | 0d | 0.005 | T | c.2060T>C | p.Leu687Pro | Missense | 13 | CTLD4 | |

| 2a | 160840584 | rs149133741 | C | A/C | 0.005 | 0.011 | G | c.2038G>T | p.Val680Leu | Missense | 13 | CTLD4 | |

| 2a | 160862197 | rs149960520 | C | C/T | 0d | 0.005 | G | c.1800G>A | p.Pro600= | Synonymous | 11 | CTLD3 | |

| 2a | 160873180 | rs140427239 | T | C/T | 0 | 0.005 | A | c.1496A>G | p.Tyr499Cys | Missense | 9 | CTLD2 2 aa from C4 | |

| 2 | 160879259 | rs33985939 | C | C/T | 0.094 | 0.041 | 0.02 | G | c.1211G>A | p.Arg404His | Missense | 7 | CTLD2 1 aa from C1 |

| 2c | 160879310 | Novel | C | C/T | 0d | 0.005 | G | c.1160G>A | p.Arg387His | Missense | 7 | CTLD2 | |

| 2a | 160879311 | rs150221555 | G | A/G | 0d | 0.006 | C | c.1159C>T | p.Arg387Cys | Missense | 7 | CTLD2 | |

| 2 | 160885418 | rs35771982b | G | G/C | 0.480 | 0.296 | 0.0000057 | C | c.898C>G | p.His300Asp | Missense | 5 | CTLD1 |

| 2 | 160885442 | rs3749117b | T | T/C | 0.485 | 0.296 | 0.0000031 | A | c.874A>G | p.Met292Val | Missense | 5 | WMGL motif of CTLD1 |

| 2a | 160889495 | rs149256089 | A | A/G | 0.001d | 0.005 | T | c.816T>C | p.Asp272= | Synonymous | 4 | CTLD1 | |

| 2a | 160898605 | rs141800672 | C | A/C | 0d | 0.005 | G | c.598G>T | p.Asp200Tyr | Missense | 2 | FNII | |

| 2 | 160901517 | rs4665143b | A | A/G | 0.629 | 0.454 | 0.000021 | T | c.261T>C | p.Ser87= | Synonymous | 2 | CRD |

| 2 | 160918984 | rs925409 | T | T/A | 0.074 | 0.080 | 0.78 | A | c.-70A>T | 5′-UTR | 1 | ||

| 2 | 160919020 | rs3749119b | C | C/T | 0.339 | 0.186 | 0.000049 | G | c.-106G>A | 5′-UTR | 1 |

Chr, chromosome; position, base pair position based on University of California, Santa Cruz, genome browser version human (February 2009) (GRCh37/hg19) assembly NC_000002.11; name, rs identifier; ref, genomic reference allele; all, alleles; CEU AF, variation allele frequencies white population from 1000 Genomes release 10 (March 2012); AF patients, patient variation allele frequencies; P value, comparison of variation allele frequencies in controls and patients; ref cDNA, reference allele cDNA (given that PLA2R1 is on the negative strand); cDNA, NM_007366.4; prot level, NP_031392.3; Ess, essential splice site; ss, splice site; aa, amino acid; WMGL, motif; FNII, fibronectin type II domain; CRD, cysteine-rich domain; UTR, untranslated region.

Rare variants.

Significantly associated with iMN.

Novel variants.

Not reported in 1000 Genomes; allele frequency from Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database, release 136.

Of the 18 variants observed, 9 were rare or novel (see the Concise Methods section for definitions). These 9 variants were all encountered in a heterozygous state in one patient each, except for the rare variant rs149133741 (c.2038G>T, p.Val680Leu), which was observed in two patients. Seven of these rare variants (rs141800672, rs149256089, rs150221555, rs140427239, rs149960520, rs149133741, and rs181959329) have been reported in publicly available data sets with very low minor allele frequencies (≤0.2%). We identified two novel missense variants that have not been previously reported, which result in amino acid changes (c.1160G>A, p.Arg387His; c.2060T>C, p.Leu687Pro). The novel variant c.1160G>A, p.Arg387His and the splice site change c.3850+1G>A (IVS26+1G>A) (rs181959329) were carried by the same patient. Additionally, nine common SNPs were observed; six of them in the coding regions (rs4665143, rs3749117, rs35771982, rs33985939, rs72954858, and rs3828323) and three in noncoding regions (rs2715918, rs925409, and rs3749119).

In the subgroup of 60 anti-PLA2R-positive patients, four of the rare variants (rs149256089, rs140427239, rs149960520, and rs149133741) were each observed once in four different patients. The two novel variants were not observed in this subgroup (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sequence variants in PLA2R1 observed in 60 anti-PLA2R1–positive patients

| Chr | Position | Name | Ref | All | CEU AF | AF Patients | P Value | Ref cDNA | cDNA | Prot Level | Effect | Exon | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 160808075 | rs3828323a | C | C/T | 0.511 | 0.381 | 0.0090 | G | c.3316G>A | p.Gly1106Ser | Missense | 24 | Linker region between CTLD6 and CTLD7 |

| 2 | 160808076 | rs72954858 | G | G/A | 0.012 | 0.042 | 0.014 | C | c.3315C>T | p.His1105= | Synonymous | 24 | Linker region between CTLD6 and CTLD7 |

| 2 | 160833188 | rs2715918a | A | A/G | 0.821 | 0.700 | 0.0020 | T | c.2437+8T>C | Intron | 16 | ||

| 2b | 160840584 | rs149133741 | C | A/C | 0.005 | 0.008 | G | c.2038G>T | p.Val680Leu | Missense | 13 | CTLD4 | |

| 2b | 160862197 | rs149960520 | C | C/T | 0c | 0.008 | G | c.1800G>A | p.Pro600= | Synonymous | 11 | CTLD3 | |

| 2b | 160873180 | rs140427239 | T | C/T | 0 | 0.008 | A | c.1496A>G | p.Tyr499Cys | Missense | 9 | CTLD2 2 aa from C4 | |

| 2 | 160879259 | rs33985939 | C | C/T | 0.094 | 0.038 | 0.055 | G | c.1211G>A | p.Arg404His | Missense | 7 | CTLD2 1 aa from C1 |

| 2 | 160885418 | rs35771982a | G | G/C | 0.480 | 0.250 | 0.0000035 | C | c.898C>G | p.His300Asp | Missense | 5 | CTLD1 |

| 2 | 160885442 | rs3749117a | T | T/C | 0.485 | 0.250 | 0.0000021 | A | c.874A>G | p.Met292Val | Missense | 5 | WMGL motif of CTLD1 |

| 2b | 160889495 | rs149256089 | A | A/G | 0.001c | 0.008 | T | c.816T>C | p.Asp272= | Synonymous | 4 | CTLD1 | |

| 2 | 160901517 | rs4665143a | A | A/G | 0.629 | 0.430 | 0.000049 | T | c.261T>C | p.Ser87= | Synonymous | 2 | CRD |

| 2 | 160918984 | rs925409 | T | T/A | 0.074 | 0.068 | 0.81 | A | c.-70A>T | 5′-UTR | 1 | ||

| 2 | 160919020 | rs3749119a | C | C/T | 0.339 | 0.152 | 0.000049 | G | c.-106G>A | 5′-UTR | 1 |

Chr, chromosome; position, base pair position based on University of California, Santa Cruz, genome browser version human (February 2009) (GRCh37/hg19) assembly NC_000002.11; name, rs identifier; ref, genomic reference allele; all, alleles; CEU AF, variation allele frequencies white population from 1000 Genomes release 10 (March 2012); AF patients, patient variation allele frequencies; P value, comparison of variation allele frequencies in controls and patients; ref cDNA, reference allele cDNA (given that PLA2R1 is on the negative strand); cDNA, NM_007366.4; prot level, NP_031392.3; aa, amino acid; WMGL, motif; FNII, fibronectin type II domain; CRD, cysteine-rich domain; UTR, untranslated region.

Significantly associated with iMN.

Rare variants.

Not reported in 1000 Genomes; allele frequency from Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database, release 136.

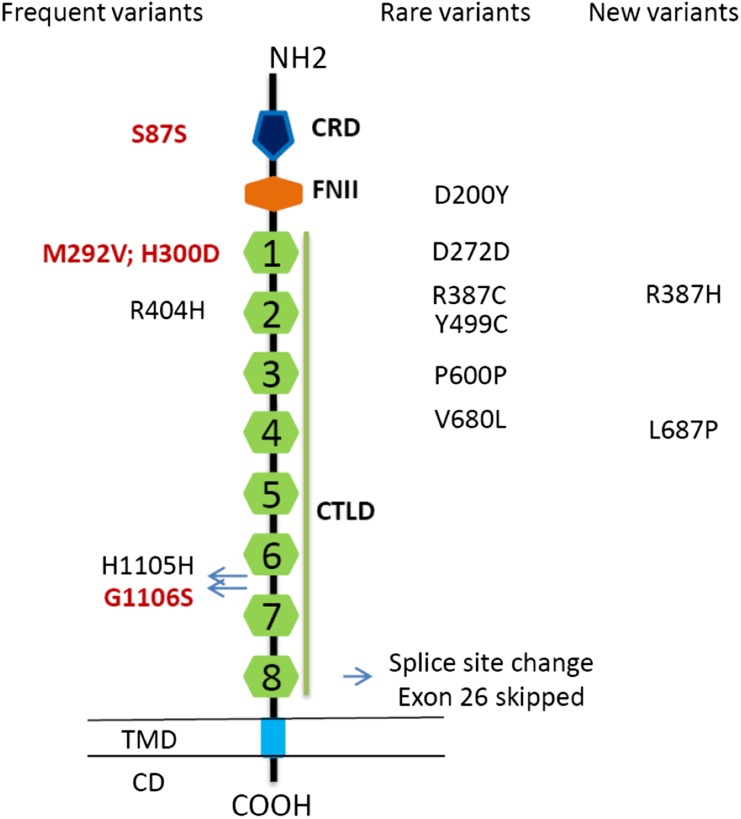

Of the 15 observed coding variants, 12 (rs149133741, rs149960520, rs140427239, rs33985939, rs150221555, rs35771982, rs3749117, rs149256089, rs141800672, rs4665143, and the novel p.Arg387His and p.Leu687Pro) are located within the regions coding for known domains of PLA2R1, of which 1 (rs3749117) is located within the WMGL motif of the C-type lectin-like domain (CTLD)-1 of PLA2R1. Two other coding variants, one common (rs33985939, p.Arg404His) and one rare (rs140427239, p.Tyr499Cys), are situated one and two amino acids, respectively, away from the cysteine residues involved in disulfide bond formation (C4 and C1 in CTLD2; see Table 1 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of PLA2R1. The amino acid sequence of PLA2R1 starts with a 20–amino acid signal peptide, followed by a large extracellular segment, a transmembrane domain, and a short intracellular domain containing an endocytosis motif. The extracellular segment contains a cystine-rich domain at the N-terminal, followed toward the membrane surface by a fibronectin type II domain and eight C-type lectin-like domains/carbohydrate recognition. CD, intracellular domain; COOH, intracellular C terminal end; CRD, cystine-rich domain (thin vertical lines, S-S bounds); FNII, fibronectin type II domain; CTLD, C-type lectin-like domain; NH2, extracellular N terminal end; TMD, transmembrane domain. In red, common variants significantly associated with iMN. Rare and new coding variants were found in only nine patients.

The essential splice site at the border between exon 26 and intron 26 is altered in one patient, c.3850+1G>A (IVS26+1G>A) (rs181959329), predicted to lead to exon 26 being skipped, which is in frame. This leads to a shortened PLA2R1 protein missing 46 amino acids within CTLD8, obliterating the first cysteine residue involved in disulfide bond formation (C1). Of note, this is a known sequence variant with a yet undetermined allele frequency in the general population.

Of note, Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database release 136 (February 2012) currently has 138 human sequence variants curated within the coding region, including splice sites of PLA2R1. Actually, only 8 of the 138 variants are frequently observed, nonsynonymous, coding variants. Minor allele frequencies were not established for most of those SNPs.

Association

The common SNPs identified by our sequencing permit us to analyze the PLA2R1 region in more detail compared with the GWAS that mainly included common intronic SNPs (typical for SNP chips used for GWAS).

In the 95 patients with iMN studied, the allele frequency of several SNPs was significantly different from that of the ethnically matched controls from the 1000 Genomes project (see Table 1). Specifically, there was a significant difference for the coding SNPs rs4665143 (p.Ser87Ser), rs3749117 (p.Met292Val), rs35771982 (p.His300Asp), and rs3828323 (p.Gly1106Ser). In addition, two of the three noncoding SNPs (rs2715918, rs3749119) were significantly associated with iMN.

The nonsynonymous SNP (rs3749117; p.Met292Val) located in the WMGL motif of CTLD1, which has been shown to be in linkage disequilibrium (r2=0.70) with the most significantly associated SNP located in the first intron from our previous GWAS (i.e., rs4664308; P=4.3×10−28) with 556 iMN cases, was significantly associated with iMN in this study (P=3.1×10−6). SNP rs4665143 was significantly associated with iMN (P=2.1×10−5), confirming our previous work.5 Two nonsynonymous SNPs identified in this study (rs35771982 [p.His300Asp] and rs3828323 [p.Gly1106Ser]) were also assessed by the two candidate gene association studies from Taiwan (p.His300Asp)6 and Korea (p.His300Asp, p.Gly1106Ser)7 and found to be significantly associated with iMN. Both SNPs reached significance for allelic association with iMN in the present study (P=1.6×10−3 for rs3828323 and P=5.7×10−6 for rs35771982). These associations were also clearly present when we limited the analysis to the anti-PLA2R1–positive subgroup (Table 2).

Discussion

In a series of three independent GWAS in biopsy-proven cases of iMN with similar genetic background (all of white ethnicity), as well as in a combined analysis of all three populations, we were able to show that HLA-DQA1 and PLA2R1 haplotypes are associated with iMN with high levels of statistical significance, with a combined odds ratio of approximately 80 for individuals homozygous for both risk alleles.5 We and others have speculated that rare sequence variants in PLA2R1, not studied by GWAS, could cause the disease.5,9 Under this hypothesis, the causal or predisposing variants of the PLA2R1 sequence would modify the structure of the protein to give rise to a peptide/epitope that would fit the antigen-presenting groove of a complementary, also causal/predisposing variant to HLA genes (e.g., HLA-DQA1). Such PLA2R1 variants might not have been covered in the earlier GWAS because of the design of the genotyping chip (which does not include all possible SNPs) or because the variant was very rare in the general population but not rare in the cohort with biopsy-proven iMN. Our study was designed to assess these possibilities and to shed further light on the genetics of iMN.

We sequenced the PLA2R1 gene in 95 patients with iMN, including 60 patients with PLA2R-related iMN as assessed by anti-PLA2R1 antibodies and PLA2R1 antigen in immune deposits. We made two important observations. First, we found nine rare variants, but in only nine patients, all in a heterozygous state, and only two of these had not been reported previously (potential “private mutations”). When we focused on the 60 patients with established PLA2R1-related MN, no “private mutations” were found, and four of the rare variants were present. It is thus evident that iMN is not caused by classic Mendelian mutations in the coding region, including splice sites of PLA2R1. Moreover, these results do not support the hypothesis that rare variants present in the coding region of PLA2R1 are responsible for the association with iMN. These findings agree with the rarity of familial forms of iMN, which could still be related to “private mutations.” Individual rare mutations in the coding region of PLA2R1 might influence antigen processing in only a minority of individuals with iMN, but data providing additional insights are lacking. Although our data allow us to make a clear-cut statement that neither rare variants nor mutations in the coding region of the PLA2R1 gene explain the proven genetic association within the PLA2R1 locus, we identified a few single rare variants in the coding region of PLA2R1 in our population.

The second important observation is that we identified six common variants in the coding regions of PLA2R1 and three more in the exon/intron boundaries (Table 1). We found a significant association between iMN and four coding and two noncoding SNPs, thus confirming that the PLA2R1 region is associated with iMN.5 Of note, three significantly associated coding SNPs were nonsynonymous. One is the nonsynonymous SNP (rs3749117; p.Met292Val; P=3.1×10−6) located in the WMGL motif of CTLD1, which was previously shown to be in strong linkage disequilibrium (r2=0.70) with the most significantly associated SNP from our previous GWAS, located in the first intron (rs4664308; P=4.3×10−28). The WMGL motif (representing tryptophan, methionine, glycine, and leucine) is one of the typical, highly conserved tetrapeptides, found as parts of CTLD β2 and β3 strands of the PLA2 receptor (Figure 1). It can be hypothesized that a single change in these residues could result in changes in binding specificity, Ca2+ sensitivity, or affinity.10,11

The other two nonsynonymous SNPs identified in this study (rs35771982; p.His300Asp and rs3828323; p.Gly1106Ser) have previously been shown, in candidate gene association studies that tested only single SNPs, to be associated with iMN by groups from Taiwan (p.His300Asp)6 and Korea (p.His300Asp, p.Gly1106Ser).7 Both SNPs reached significance for allelic association with iMN in the present study (P=1.6×10−3 for rs3828323 and P=5.7×10−6 for rs35771982) and might be particularly relevant also because they were identified in ethnically distant populations. p.M292V, p.His300Asp, and p.Gly1106Ser are responsible for important amino acid substitutions that may change the antigenicity or biologic properties of PLA2R1 as a receptor.

Little is known about the process of antibody formation and the pathogenic epitopes of PLA2R1. PLA2R1 is a type I single-pass transmembrane protein member of the mannose receptor family, which is a member of the C-type lectin superfamily, itself one of the families of membrane-bound pattern recognition receptors (Figure 1).10–12 It has been suggested that the potential autoantigenic region resides in the N-terminal part of the receptor because human anti-PLA2R1 antibodies recognized a shortened form of the receptor, consisting of the carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD), the fibronectin type II domain, and CTLD 1–3.13 Of note, two nonsynonymous common variants identified in this study (p.Met292Val and p.His300Asp) are located in this putative epitope, whereas a third variant, Arg404His, with the same location did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1). Receptors in the mannose receptor family can present with at least two configurations: a straight extended conformation with the N-terminal CRD pointing outward from the cell surface and a bent conformation in which the N-terminal CRD is folded back to interact with CTLDs at the middle of the structure. The different configurations affect ligand binding and oligomerization. Anti-PLA2R1 antibodies are directed to a reduction-sensitive epitope,3 which might occur in only one of the two conformations.1,14 The concept of the role of conformational changes in antibody formation was developed by Hudson’s group, who demonstrated that changes in the molecular architecture of the α345-collagen IV autoantigen play a key role in eliciting an autoimmune response in Goodpasture syndrome.15 The PLA2R1 sequencing data do not provide a simple genetic basis for iMN as another “conformeropathy.” However, the combined effects of the nonsynonymous variants significantly associated with iMN might alter the conformational changes resulting in subtle alterations of antigenic properties.

Sequence variants may also affect PLA2R1 function, irrespective of its antigenic properties (i.e., binding to antibody). PLA2R1 is a multifunctional receptor, and its CTLDs are involved in several functions, such as extracellular matrix organization, endocytosis, complement activation, and cell-to-cell interactions.16,17 Alterations in these domains, especially a residue change (p.Met292Val, p.His300Asp) in the first CTLD, may alter these important functions.

This study confirmed the association between PLA2R1 (by use of common coding SNPs) and iMN. This may raise the question as to why iMN is rare if these SNPs occur frequently in the general population. We speculate that a combination of known common variants may result in rare haploblocks conferring susceptibility to iMN and that a contingency of causality on more than one predisposing gene may occur, given our previous study showing that iMN is independently associated with variants in at least one molecule encoded in the HLA region on the short arm of chromosome 6.5 Also, a rare combination of (relatively) common events (genetic variants or environmental factors) might constitute the pathogenetic trigger. For example, a variant enhancing the podocyte expression of PLA2R1 in the context of an infectious event might coincide with a variant modifying the conformation of the receptor (possibly under specific chemical or environmental constrains, such as heavy-metal presence and drugs). This novel structure would then be recognized as an intrinsic epitope and presented by an HLA gene (e.g., HLA-DQ receptor) correspondingly shaped by another variant to the effector arm of the immune system, triggering the autoimmune response, which would lead to iMN-type lesions.

Thus, we believe the rarity of iMN can be explained by the underlying genetic basis we are proposing (e.g., the co-occurrence of three or more relatively frequent independent events [i.e., presence of one or more PLA2R1 risk alleles, possibly combined in a rare haplotype; similarly, occurrence of HLA risk alleles or haploblocks; and environmental trigger factors]) leading to a rare outcome event (onset of iMN). Further studies (genetic and functional) are needed to elucidate this potential mechanism.

Our study has several limitations. We selected patients from the Dutch and French cohort because the British DNA collection has no sufficient antibody status linked to it. It is possible that a minority of the British patients also would have similar or other rare variants. Given the similarity among the three populations, we consider it unlikely that the proportion of novel mutations would be grossly different. Another limitation of this study is that causal noncoding variants could have been missed because we sequenced only exons and essential splice sites. Other potential regions of interest, not sequenced in this study, include putative regulatory regions, which might affect the splicing pattern (exonic or intronic splicing enhancers or silencers) and/or the intensity (quantity) or (temporo-spatial) quality of the expression of PLA2R1 isoforms (i.e., promoter region, transcription factor–binding sites, enhancer regions, inhibitor regions, insulator elements, matrix attachment regions, micro RNA coding, and/or binding sites). A more comprehensive sequencing approach would be required to investigate this.

In summary, in 95 biopsy-proven cases, including 60 PLA2R1 antibody–positive cases of iMN, we found no evidence for our initial hypothesis that rare variants within the coding region of PLA2R1 cause the association between iMN and the PLA2R1 gene. This observation is important because it could prevent other investigators from engaging in further labor and cost-intensive sequencing of PLA2R1 exons in the quest for potential rare pathogenic PLA2R1-coding region variants. Second, by performing a sequence-based association study of the complete PLA2R1 coding region, we can now confirm on a single base-pair level the findings of our previous GWAS, which was based predominantly on common intronic SNPs. That is, there are significant associations between informative coding variants within PLA2R1 and iMN. Third, this study suggests that the strong genetic association between iMN and PLA2R1 is due to intronic regions harboring rare variants or a combination of common variants forming a rare haploblock.

Concise Methods

Patients

The European Membranous Nephropathy consortium enrolled Dutch, French, and British cohorts to establish the relation between the PLA2R1 gene and the development of iMN. For this study, we analyzed 95 biopsy-proven patients from the Dutch and French cohorts. In all patients, the diagnosis of iMN was established by renal biopsy, and secondary causes were excluded according to local routine clinical workup.5 Baseline data on age, sex, and ethnicity were available for all patients. Furthermore, presence of anti-PLA2R1 antibodies was evaluated. Because this was a cross-sectional cohort, sera or biopsy specimens were not available for all patients. It is well established that antibodies can disappear after presentation.18 Anti-PLA2R1 positivity was therefore based on the presence of antibodies in the serum or the presence of the antigen in deposits in a renal biopsy specimen.19 The assays for measuring anti-PLA2R1 antibodies and detecting PLA2R1 in kidney biopsy samples have been described previously.19

The study was approved by the ethics committees of the participating institutions. All Dutch and French patients gave written informed consent before participation in the study.

Sequencing

DNA was isolated using salt extraction according to a previously described method.20 All exons, including all coding exons and splice sites of PLA2R1, were sequenced using genomic DNA. Primers were designed using Primer3.21 PCR primers and conditions are given in Supplemental Table S2. PCR products were purified using Multiscreen filter plates (Millipore, Carrigtwohill, Cork, Ireland). Purified products were used for Sanger sequence analysis (unidirectional) with a dye-termination chemistry (BigDye Terminator, version 3) on a 3730 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA).

Analysis

The sequences of PLA2R1 were investigated for the presence of all genetic variants in comparison with the published reference sequence (mRNA NM_007366.4; protein NP_031392.3). Ethnically matched allele frequencies were obtained from the 1000 Genomes project (release 10, March 2012) and from the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database, release 136.

Variants were considered to be common (previously reported with allele frequency >1%), rare (previously reported with allele frequency <1%), or novel (not previously reported in 1000 Genome project or the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database, release 136).

Genotype data of 379 white controls were downloaded from the 1000 Genomes project (release 10, March 2012; details provided in Supplemental Table S3).22 Using these data and the data of our cohort, association analyses, and statistic analyses were performed using PLINK.23 Significance was conservatively set at P=0.01.

PLA2R1 was annotated using the custom track functionality of the Genome Browser at the University of California, Santa Cruz;24 its domain structure is based on UniProt entry Q13018; C-type lectin domain substructure is based on the published literature.25

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement 2012-305608 “European Consortium for High-Throughput Research in Rare Kidney Diseases” (EURenOmics)” (to P.W.M., P.E.B., R.K., J.F.M.W., P.R.), by the David and Elaine Potter Charitable Foundation (to S.H.P., R.K.), by the Dutch Kidney Foundation (J.M.H., grant KJPB11.021), and by the French Foundation for Medical Research (H.D., P.R., grant 2012). The French Gn-Progress cohort was supported by grants from the French Ministry of Health (PHRC AOM 00022), the Ministry of Research (Decision d’aide 01P0513), and the Biomedicine Agency (AO Recherche et Greffes 2005).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Genetic Variants in Membranous Nephropathy: Perhaps a Perfect Storm Rather than a Straightforward Conformeropathy?,” on pages 525–528.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2012070730/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ronco P, Debiec H: Pathogenesis of membranous nephropathy: Recent advances and future challenges. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 203–213, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Debiec H, Guigonis V, Mougenot B, Decobert F, Haymann JP, Bensman A, Deschênes G, Ronco PM: Antenatal membranous glomerulonephritis due to anti-neutral endopeptidase antibodies. N Engl J Med 346: 2053–2060, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck LH, Jr, Bonegio RG, Lambeau G, Beck DM, Powell DW, Cummins TD, Klein JB, Salant DJ: M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med 361: 11–21, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofstra JM, Wetzels JF: Anti-PLA₂R antibodies in membranous nephropathy: Ready for routine clinical practice? Neth J Med 70: 109–113, 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanescu HC, Arcos-Burgos M, Medlar A, Bockenhauer D, Kottgen A, Dragomirescu L, Voinescu C, Patel N, Pearce K, Hubank M, Stephens HA, Laundy V, Padmanabhan S, Zawadzka A, Hofstra JM, Coenen MJ, den Heijer M, Kiemeney LA, Bacq-Daian D, Stengel B, Powis SH, Brenchley P, Feehally J, Rees AJ, Debiec H, Wetzels JF, Ronco P, Mathieson PW, Kleta R: Risk HLA-DQA1 and PLA(2)R1 alleles in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med 364: 616–626, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu YH, Chen CH, Chen SY, Lin YJ, Liao WL, Tsai CH, Wan L, Tsai FJ: Association of phospholipase A2 receptor 1 polymorphisms with idiopathic membranous nephropathy in Chinese patients in Taiwan. J Biomed Sci 17: 81, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim S, Chin HJ, Na KY, Kim S, Oh J, Chung W, Noh JW, Lee YK, Cho JT, Lee EK, Chae DW, Progressive Renal Disease and Medical Informatics and Genomics Research (PREMIER) members : Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the phospholipase A2 receptor gene are associated with genetic susceptibility to idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Nephron Clin Pract 117: c253–c258, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein RJ, Zeiss C, Chew EY, Tsai JY, Sackler RS, Haynes C, Henning AK, SanGiovanni JP, Mane SM, Mayne ST, Bracken MB, Ferris FL, Ott J, Barnstable C, Hoh J: Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science 308: 385–389, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segelmark M: Genes that link nephritis to autoantibodies and innate immunity. N Engl J Med 364: 679–680, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graversen JH, Lorentsen RH, Jacobsen C, Moestrup SK, Sigurskjold BW, Thogersen HC, Etzerodt M: The plasminogen binding site of the C-type lectin tetranectin is located in the carbohydrate recognition domain, and binding is sensitive to both calcium and lysine. J Biol Chem 273: 29241–29246, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weis WI, Drickamer K: Structural basis of lectin-carbohydrate recognition. Annu Rev Biochem 65: 441–473, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambeau G, Ancian P, Barhanin J, Lazdunski M: Cloning and expression of a membrane receptor for secretory phospholipases A2. J Biol Chem 269: 1575–1578, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck LH: The human membranous antibody: mechanism and monitoring. ASN Renal Week. November 19, 2010. Available at: http://asn.sclivelearningcenter.com/index.aspx?PID=1840&SID=80319 Accessed July 23, 2012

- 14.Debiec H, Nauta J, Coulet F, van der Burg M, Guigonis V, Schurmans T, de Heer E, Soubrier F, Janssen F, Ronco P: Role of truncating mutations in MME gene in fetomaternal alloimmunisation and antenatal glomerulopathies. Lancet 364: 1252–1259, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedchenko V, Bondar O, Fogo AB, Vanacore R, Voziyan P, Kitching AR, Wieslander J, Kashtan C, Borza DB, Neilson EG, Wilson CB, Hudson BG: Molecular architecture of the Goodpasture autoantigen in anti-GBM nephritis. N Engl J Med 363: 343–354, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weis WI, Taylor ME, Drickamer K: The C-type lectin superfamily in the immune system. Immunol Rev 163: 19–34, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day AJ: The C-type carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) superfamily. Biochem Soc Trans 22: 83–88, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofstra JM, Beck LH, Jr, Beck DM, Wetzels JF, Salant DJ: Anti-phospholipase A₂ receptor antibodies correlate with clinical status in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1286–1291, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Debiec H, Ronco P: PLA2R autoantibodies and PLA2R glomerular deposits in membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med 364: 689–690, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF: A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 16: 1215, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rozen S, Skaletsky H: Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol 132: 365–386, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.1000 Genomes Project Consortium : A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 467: 1061–1073, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC: PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 81: 559–575, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D: The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res 12: 996–1006, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zelensky AN, Gready JE: The C-type lectin-like domain superfamily. FEBS J 272: 6179–6217, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]