Abstract

Syzygium cumini (S. cumini) (L.) Skeels (jambolan) is one of the widely used medicinal plants in the treatment of various diseases in particular diabetes. The present review has been primed to describe the existing data on the information on botany, phytochemical constituents, traditional uses and pharmacological actions of S. cumini (L.) Skeels (jambolan). Electronic database search was conducted with the search terms of Eugenia jambolana, S. cumini, jambolan, common plum and java plum. The plant has been viewed as an antidiabetic plant since it became commercially available several decades ago. During last four decades, numerous folk medicine and scientific reports on the antidiabetic effects of this plant have been cited in the literature. The plant is rich in compounds containing anthocyanins, glucoside, ellagic acid, isoquercetin, kaemferol and myrecetin. The seeds are claimed to contain alkaloid, jambosine, and glycoside jambolin or antimellin, which halts the diastatic conversion of starch into sugar. The vast number of literatures found in the database revealed that the extracts of different parts of jambolan showed significant pharmacological actions. We suggest that there is a need for further investigation to isolate active principles which confer the pharmacological action. Hence identification of such active compounds is useful for producing safer drugs in the treatment of various ailments including diabetes.

Keywords: Syzygium cumini, Medicinal uses, Myrtaceae, Phytochemistry, Traditional uses, Jambolan, Common plum, Java plum, Eugenia jambolana

1. Introduction

The genus Syzygium is one of the genera of the myrtle family Myrtaceae which is native to the tropics, particularly to tropical America and Australia. It has a worldwide, although highly uneven, distribution in tropical and subtropical regions. The genus comprises about 1 100 species, and has a native range that extends from Africa and Madagascar through southern Asia east through the Pacific. Its highest levels of diversity occur from Malaysia to northeastern Australia, where many species are very poorly known and many more have not been described taxonomically. Plants of this family are known to be rich in volatile oils which are reported for their uses in medicine[1] and many fruits of the family have a rich history of uses both as edibles and as traditional medicines in divergent ethnobotanical practices throughout the tropical and subtropical world[2]. Some of the edible species of Syzygium are planted throughout the tropics worldwide.

2. History and distribution

Syzygium cumini (S. cumini) (L.) Skeels is one of the best known species and it is very often cultivated. The synonyms of S. cumini are Eugenia jambolana Lam., Myrtus cumini Linn., Syzygium jambolana DC., Syzygium jambolanum (Lam.) DC., Eugenia djouant Perr., Calyptranthes jambolana Willd., Eugenia cumini (Linn.) Druce. and Eugenia caryophyllifolia Lam. It is commonly known as jambolan, black plum, jamun, java plum, Indian blackberry, Portuguese plum, Malabar plum, purple plum, Jamaica and damson plum.

For long in the period of recorded history, the tree is known to have grown in the Indian sub-continent, and many others adjoin regions of South Asia such as India, Bangladesh, Burma, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Indonesia. It was long ago introduced into and became naturalized in Malaysia. In southern Asia, the tree is venerated by Buddhists, and it is commonly planted near Hindu temples because it is considered sacred to Lord Krishna[3]. The plant has also been introduced to many different places where it has been utilized as a fruit producer, as an ornamental and also for its timber. In India, the plant is available throughout the plains from the Himalayas to southern India.

3. Botany

Jambolan is a large evergreen and densely foliaceous tree with greyish-brown thick bark, exfoliating in woody scales. The wood is whitish, close grained and durable; affords brown dyes and a kind of a gum Kino. The leaves are leathery, oblong-ovate to elliptic or obovate-elliptic with 6 to 12 centimeters long (extremely variable in shape, smooth and shining with numerous nerves uniting within the margin), the tip being broad and less acuminate. The panicles are borne mostly from the branchlets below the leaves, often being axillary or terminal, and are 4 to 6 centimeters long. Flowers are scented, greenish-white, in clusters of just a few or 10 to 40 and are round or oblong in shape and found in dichotomous paniculate cymes. The calyx is funnel-shaped, about 4 millimeters long, and toothed. The petals cohere and fall all together as a small disk. The stamens are numerous and about as long as the calyx. Several types, which differ in colour and size of fruits, including some improved races bearing purple to violet or white coloured flesh and seedless fruits have been developed. The fruits are berries and are often obviously oblong, 1.5 to 3.5 centimeters long, dark-purple or nearly black, luscious, fleshy, and edible; it contains a single large seed[4],[5]. The plant produces small purple plums, which have a very sweet flavor, turning slightly astringent on the edges of the pulp as the fruit becomes mature. The dark violet colored ripe fruits give the impression the fruit of the olive tree both in weight and shape and have an astringent taste[6]. The fruit has a combination of sweet, mildly sour and astringent flavour and tends to colour the tongue purple.

4. Phytochemical constituents

Jambolan is rich in compounds containing anthocyanins, glucoside, ellagic acid, isoquercetin, kaemferol and myrecetin. The seeds are claimed to contain alkaloid, jambosine, and glycoside jambolin or antimellin, which halts the diastatic conversion of starch into sugar and seed extract has lowered blood pressure by 34.6% and this action is attributed to the ellagic acid content[3]. The seeds have been reported to be rich in flavonoids, a well-known antioxidant, which accounts for the scavenging of free radicals and protective effect on antioxidant enzymes[7],[8] and also found to have high total phenolics with significant antioxidant activity[9] and are fairly rich in protein and calcium. Java plums are rich in sugar, mineral salts, vitamins C, PP which fortifies the beneficial effects of vitamin C, anthocyanins and flavonoids[10].

4.1. Leaves

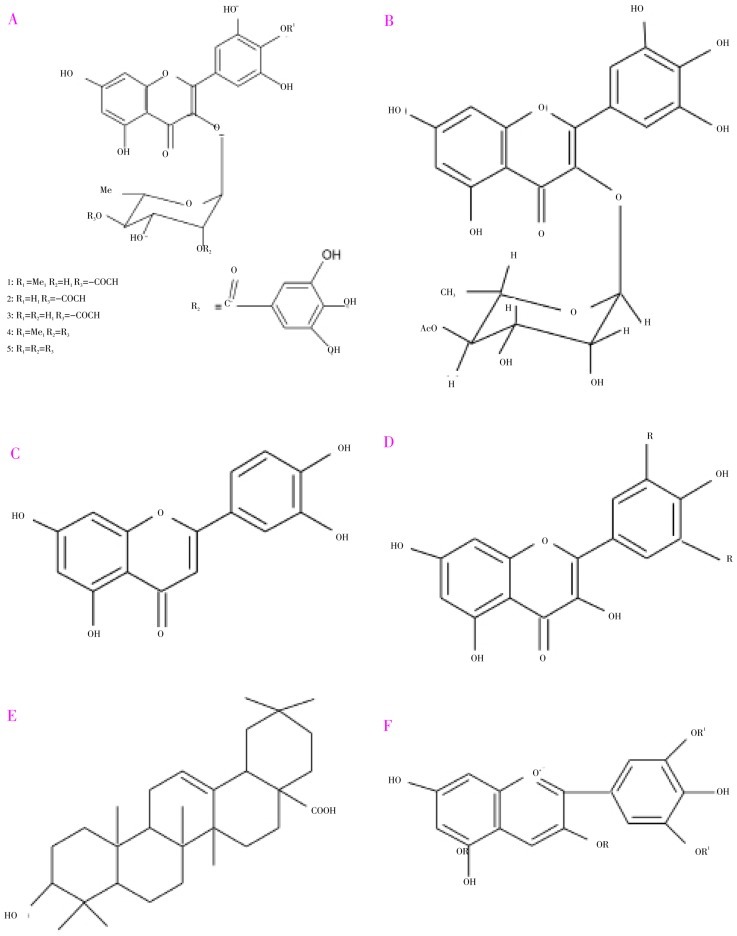

The leaves are rich in acylated flavonol glycosides[1] (Figure 1A), quercetin, myricetin, myricitin, myricetin 3-O-4-acetyl-L-rhamnopyranoside[11] (Figure 1B), triterpenoids[12], esterase, galloyl carboxylase[13], and tannin[3].

Figure 1. Phytochemical constituents isolated from S. cumini (L.) Skeels.

A: Mearnsetin -3-O-(400-O-acetyl)-a-L-rhamnopyranoside (1), myricetin 3-O-(400-O-acetyl-200-O-galloyl)-a-L-rhamnopyranoside (2), myricetin 3-O-(400-O-acetyl)-a-L-rhamnopyranoside (3), myricetin 40-methyl ether 3-O-a-l-rhamnopyranoside (4), myricerin (5); B: Myricetin 3-O-(4″-acetyl)-α-L-rhamnopyranoside; C: Quercetin; D: Kaempferol R=H; Myricetin R= OH; E: Oleanolic acid; F: Delphinidin-3-gentiobioside R = Gentiobiose, R1 = H: Malvidine-3-laminaribioside R = Laminaribiose R1 = Me.

4.2. Stem bark

The stem bark is rich in betulinic acid, friedelin, epi-friedelanol, β-sitosterol, eugenin and fatty acid ester of epi-friedelanol[14], β-sitosterol, quercetin kaempferol, myricetin (Figure 1C and Figure 1D), gallic acid and ellagic acid[15], bergenins[16], flavonoids and tannins[17]. The presence of gallo- and ellagi-tannins may be responsible for the astringent property of stem bark.

4.3. Flowers

The flowers are rich in kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, isoquercetin (quercetin-3-glucoside), myricetin-3-L-arabinoside, quercetin-3-D-galactoside, dihydromyricetin[18], oleanolic acid (Figure 1E), acetyl oleanolic acid, eugenol-triterpenoid A and eugenol-triterpenoid B[18].

4.4. Roots

The roots are rich in flavonoid glycosides[19] and isorhamnetin 3-O-rutinoside[20].

4.5. Fruits

The fruits are rich in raffinose, glucose, fructose[21], citric acid, mallic acid[22], gallic acid, anthocyanins[23]; delphinidin-3-gentiobioside, malvidin-3-laminaribioside, petunidin-3-gentiobioside[24] (Figure 1F)[24], cyanidin diglycoside, petunidin and malvidin[25]. The sourness of fruits may be due to presence of gallic acid. The color of the fruits might be due to the presence of anthocyanins[24]. The fruit contains 83.70–85.80 g moisture, 0.70–0.13 g protein, 0.15–0.30 g fat, 0.30–0.90 g crude fiber, 14.00 g carbohydrate, 0.32–0.40 g ash, 8.30–15.00 mg calcium, 35.00 mg magnesium, 15.00–16.20 mg phosphorus, 1.20–1.62 mg iron, 26.20 mg sodium, 55.00 mg potassium, 0.23 mg copper, 13.00 mg sulfur, 8.00 mg chlorine, 80 I.U. vitamin A, 0.01–0.03 mg thiamine, 0.009–0.01 mg riboflavin, 0.20–0.29 mg niacin, 5.70–18.00 mg ascorbic acid, 7.00 mg choline and 3.00 mcg folic acid per 100 g of edible portion[26]. One of the variety of jambolan found in the Brazil possesses malvidin-3-glucoside and petunidin-3-glucoside[27]. The peel powder of jambolan also can be employed as a colorant for foods and pharmaceuticals and anthocyanin pigments from fruit peels were studied for their antioxidant efficacy stability as extract and in formulations[28].

4.6. Essential oils

The essential oils isolated from the freshly collected leaf (accounting for 82% of the oil)[29], stem, seed, fruits contain α-Pinene, camphene, β-Pinene, myrcene, limonene, cis-Ocimene, trans-Ocimene, γ-Terpinene, terpinolene, bornyl acetate, α-Copaene, β-Caryophyllene, α-Humulene, γ-Cadinene and δ-Cadinene[6], trans-ocimene, cis-ocimene, β-myrcene, α-terpineol, dihydrocarvyl acetate, geranyl butyrate, terpinyl valerate[30], α-terpineol, β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, β-selinene, calacorene, α-muurolol, α-santalol, cis-farnesol: lauric, myristic, palmitic, stearic, oleic, linoleic, malvalic, sterculic and vernolic acids[31]. Unsaponifiable matter of the seed fat was also chemically investigated[32].

5. Medicinal properties

The bark is acrid, sweet, digestive, astringent to the bowels, anthelmintic and used for the treatment of sore throat, bronchitis, asthma, thirst, biliousness, dysentery and ulcers. It is also a good blood purifier. The fruit is acrid, sweet, cooling and astringent to the bowels and removes bad smell form mouth, biliousness, stomachic, astringent, diuretic and antidiabetic[33]. The fruit has a very long history of use for various medicinal purposes and currently has a large market for the treatment of chronic diarrhea and other enteric disorders[28]. The seed is sweet, astringent to the bowels and good for diabetes. The ash of the leaves is used for strengthening the teeth and gums. Vinegar prepared from the juice of the ripe fruit is an agreeable stomachic and carminative and used as diuretic[34] and it is also useful in spleen enlargement and an efficient astringent in chronic diarrhea.

Juice of tender leaves of this plant, leaves of mango and myrobalan are mixed and administered along with goat's milk and honey to treat dysentery with bloody discharge, whereas juice of tender leaves alone or in combination with carminatives such as cardamom or cinnamon is given in goat's milk to treat diarrhoea in children[33]. Traditional medical healers in Madagascar have been using the seeds of jambolan for generations as the centerpiece of an effective therapy for counteracting the slow debilitating impacts of diabetes[35]. The seed extract is used to treat cold, cough, fever and skin problems such as rashes and the mouth, throat, intestines and genitourinary tract ulcers (infected by Candida albicans) by the villagers of Tamil Nadu[36]. Jambolan fruit can be eaten raw and can be made into tarts, sauces and jams. Good quality jambolan juice is excellent for sherbet, syrup and “squash”, an Indian drink.

6. Uses in traditional medicine

All parts of the jambolan can be used medicinally and it has a long tradition in alternative medicine. From all over the world, the fruits have been used for a wide variety of ailments, including cough, diabetes, dysentery, inflammation and ringworm[2]. It is also an ancient medicinal plant with an illustrious medical history and has been the subject of classical reviews for over 100 years. It is widely distributed throughout India and ayurvedic medicine (Indian folk medicine) mentions its use for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Various traditional practitioners in India use the different parts of the plant in the treatment of diabetes, blisters in mouth, cancer, colic, diarrhea, digestive complaints, dysentery, piles, pimples and stomachache[37]. During last four decades, numerous folk medicinal reports on the antidiabetic effects of this plant have been cited in the literature (Table 1). In Unani medicine various parts of jambolan act as liver tonic, enrich blood, strengthen teeth and gums and form good lotion for removing ringworm infection of the head[38].

Table 1. Folk medicinal uses of S. cumini (L.) Skeels.

| Ethnic group used and their origin | Plant part used, mode of preparation, administration and ailments treated | References |

| Local people in southern Brazil | Either infusions or decoctions of leaves of jambolan in water at an average concentration of 2.5 g/L and drank it in place of water at a mean daily intake of about 1 liter are used in the treatment of diabetes. | [74] |

| Lakher and Pawi in North east India | Infusion of fruit or mixture of powdered bark and fruit is given orally to treat diabetes. | [75] |

| Juice obtained from the seeds is applied externally on sores and ulcers. | ||

| Powdered seeds are mixed with sugar are given orally 2–3 times daily in the treatment of dysentery. | ||

| The juice of leaves is given orally as antidote in opium poisoning and in centipede bite. | ||

| The juice of ripe fruits is stored for 3 days and then is given orally for gastric problems. | ||

| The juice obtained from the bark is given orally for the treatment of women with a history of repeated abortion. | ||

| Local informants in Maharastra, India | Fruit and stem bark are used in the treatment of diabetes, dysentery, increases appetite and to relieve from headache | [76] |

| Nepalese, Lepchas and Bhutias in northeast India | Decoction of stem bark is taken orally three times a day for 2–3 weeks to treat diabetes | [77] |

| Native amerindians and Quilombolas in North eastern Brazil | Leaves are used in the treatment of diabetes and renal problems. | [78] |

| Kani tribals in Southern India | Two teaspoon of juice extracted from the leaf is mixed with honey or cow's milk and taken orally taken twice a day after food for 3 months to treat diabetes. Fresh fruits are also taken orally to get relief from stomachache and to treat diabetes. | [79] |

| Young leaf is ground into a paste with goat's milk and taken orally to treat indigestion. | ||

| Malayalis in South India | Paste of seeds is prepared with the combination of leaves of Momordica charantia and flowers of Cassia auriculata and taken orally once a day for 3 months to treat diabetes. | [80] |

| Traditional medical healers in Madagascar | Seeds are taken orally for generations as the centerpiece of an effective therapy for counteracting the slow debilitating impacts of diabetes. | [35] |

| Local population in Andhra Pradesh, India | Shade dried seeds are made into powder and taken orally thrice a day in the treatment of diabetes. | [81] |

| Siddis in Karnataka, India | The juice obtained from the leaves is mixed with milk and taken orally early in the morning, to treat diabetes. | [82] |

| The juice obtained from the stem bark is mixed with butter milk and taken orally every day before going to bed to treat constipation. The same recipe, when taken early in the morning on an empty stomach, is claimed to stop blood discharge in the faeces. | ||

| Rural population in Brazil | Leaves of jambolan are taken orally in the treatment of diabetes. | [64] |

| Traditional healers in Brazil |

Tea prepared from the infusion or decoction of leaves is taken orally to treat diabetes. |

[83] |

| Tribal people in Maharastra | The tender leaves are taken orally to treat jaundice. It was claimed that the eyes, nails and urine turned yellow. The treatment was followed for 2–3 days by adults and children as well. | [84] |

The plant has been viewed as an antidiabetic plant since it became commercially available several decades ago. In the early 1960s to 1970s, some preliminary reports on the antidiabetic activity of different parts of jambolan in diabetic animals were reported. Most of these studies have been conducted using crude preparation of the plant without pointing out their chemical profile and antidiabetic action in animals is not fully understood. A number of herbal formulations were also prepared in combination with this plant available in market which showed potential antidiabetic activity and are used regularly by diabetic patients on the advice of the physicians. Different parts of the jambolan were also reported for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuropsycho-pharmacological, anti-microbial, anti-bacterial, anti-HIV, antileishmanial and antifungal, nitric oxide scavenging, free radical scavenging, anti-diarrheal, antifertility, anorexigenic, gastroprotective and anti-ulcerogenic and radioprotective activities[38].

7. Pharmacological actions of jambolan

Different parts of the jambolan especially fruits, seeds and stem bark possess promising activity against diabetes mellitus and it has been confirmed by several experimental and clinical studies. In the early 1960s to 1970s, Chirvan-Nia and Ratsimamanga[39], Sigogneau-Jagodzinski et al[40], Lal and Choudhuri[41], Shrotri et al[42], Bose and Sepha[43] and Vaish[44] reported the antidiabetic activity of various parts of jambolan in diabetic animals. Tea prepared from leaves of jambolan was reported to have antihyperglycemic effect[45]. The stem bark of the plant could induce the appearance of positive insulin staining cells in the epithelia of the pancreatic duct of treated animals[46] and a significant decrease in blood glucose levels was also observed in mice treated with the stem bark by oral glucose tolerance test[47]. Many clinical and experimental studies suggest that, different parts of the jambolan especially fruits and seeds possess promising activity against diabetes mellitus[7],[48]–[53].

Despite tremendous advancements have been made in the field of diabetic treatments, several earlier investigations have been reported from the different parts of jambolan with antioxidant[54],[55], anti-inflammatory[56]–[58], neuropsycho-pharmacological[59], anti-microbial[36], anti-bacterial[60]–[62], anti-HIV[63], antileishmanial and antifungal[64], nitric oxide scavenging[65], free radical scavenging[66], anti-diarrheal[67], antifertility[68], anorexigenic[69], gastroprotective and anti-ulcerogenic[70], behavioural effects[71] and radioprotective[72] activities. Besides the above, the effect of various concentrations of the leaf extracts of the plant on the radiation-induced micronuclei formation was studied by Jagetia and Baliga[73].

8. Conclusions

Jambolan is widely used by the traditional healers for the treatment of various diseases especially diabetes and related complications. The plant has many important compounds which confer the most of the characteristics of the plant. Most pharmacological works on diabetes were carried out with seeds but the pharmacological potential of the other parts of the plant is required to explore in detail. Similarly, not many works are there with pharmacological actions of phytochemical constituents of jambolan. Based on these facts, the authors hope that this review highlights the role of jambolan in various treatments and recommend that further phytochemical and clinical research should be done on this traditional medicinal plant for the discovery of safer drugs.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author (M Ayyanar) gratefully acknowledges University Grants Commission (UGC), New Delhi for financial support in the form of Dr. DS Kothari Post Doctoral Fellowship [Ref. No. F.4-2/2006 (BSR)/13-98/2008(BSR)] for preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Foundation Project: This work was fianancially supported by University Grants Commission, New Delhi [grant No. F.4-2/2006(BSR)/13-98/2008(BSR)].

Conflict of interest statement: We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mahmoud II, Marzouk MS, Moharram FA, El-Gindi MR, Hassan AM. Acylated flavonol glycosides from Eugenia jambolana leaves. Phytochemistry. 2001;58:1239–1244. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00365-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reynertson KA, Basile MJ, Kennelly EJ. Antioxidant potential of seven myrtaceous fruits. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2005;3:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morton J. Fruits of warm climates. Miami: Julia Morton Winterville North Carolina; p. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gamble JS. The flora of the presidency of Madras. London: Adlard & Son LTD; 1935. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hooker JD. The flora of British India. London: Nabu Press; 1879. p. 499. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craveiro AA, Andrade CHS, Matos FJA, Alencer JW, Machado MIL. Essential oil of Eugenia jambolana. J Nat Prod. 1983;46:591–592. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravi K, Ramachandran B, Subramanian S. Protective effect of Eugenia jambolana seed kernel on tissue antioxidants in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:1212–1217. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravi K, Ramachandran B, Subramanian S. Effect of Eugenia jambolana seed kernel on antioxidant defense system in streptozotocin induced diabetes in rats. Life Sci. 2004a;75:2717–2731. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bajpai M, Pande A, Tewari SK, Prakash D. Phenolic contents and antioxidant activity of some food and medicinal plants. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2005;56:287–291. doi: 10.1080/09637480500146606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Council of Scientific and Industrial Research . The wealth of India. New Delhi: Council of Scientific and Industrial Research; 1948. 1976 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timbola AK, Szpoganicz B, Branco A, Monache FD, Pizzolatti MG. A new flavonoid from leaves of Eugenia jambolana. Fitoterapia. 2002;73:174–176. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta GS, Sharma DP. Triterpenoid and other constituents of Eugenia jambolana leaves. Phytochemistry. 1974;13:2013–2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatia IS, Sharma SK, Bajaj KL. Esterase and galloyl carboxylase from Eugenia jambolana leaves. Indian J Exp Biol. 1974;12:550–552. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sengupta P, Das PB. Terpenoids and related compunds part IV triterpenoids the stem-bark of Eugenia jambolana Lam. Indian Chem Soc. 1965;42:255–258. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhargava KK, Dayal R, Seshadri TR. Chemical components of Eugenia jambolana stem bark. Curr Sci. 1974;43:645–646. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kopanski L, Schnelle G. Isolation of bergenin from barks of Syzygium cumini. Plant Med. 1988;54:572. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-962577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatia IS, Bajaj KL. Chemical constituents of the seeds and bark of Syzygium cumini. Plant Med. 1975;28:347–352. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1097868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nair RAG, Subramanian SS. Chemical examination of the flowers of Eugenia jambolana. J Sci Ind Res. 1962;21B:457–458. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaishnava MM, Tripathy AK, Gupta KR. Flavonoid glycosides from roots of Eugenia jambolana. Fitoterapia. 1992;63:259–260. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaishnava MM, Gupta KR. Isorhamnetin 3-O-rutinoside from Syzygium cumini Lam. J Indian Chem Soc. 1990;67:785–786. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srivastava HC. Paper chromatography of fruit juices. J Sci Ind Res. 1953;12B:363–365. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis YS, Dwarakanath CT, Johar DS. Acids and sugars in Eugenia jambolana. J Sci Ind Res. 1956;15C:280–281. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain MC, Seshadri TR. Anthocyanins of Eugenia jambolana fruits. Indian J Chem. 1975;3:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venkateswarlu G. On the nature of the colouring matter of the jambul fruit (Eugenia jambolana) J Indian Chem Soc. 1952;29:434–437. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma JN, Sheshadri TR. Survey of anthocyanins from Indian sources Part II. J Sci Ind Res. 1955;14:211–214. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noomrio MH, Dahot MU. Nutritive value of Eugenia jambosa fruit. J Islam Acad Sci. 1996;9:1. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lago ES, Gomes E, da Silva R. Extraction and anthocyanic pigment quantification of the Jamun fruit (Syzygium cumini Lam.) 2004. [Online] Available from: http// www.iqsc.usp.br/outros/eventos/2004/bmcfb/trabalhos/docs/trab-76.pdf. [Accessed on 20 August, 2010]

- 28.Veigas JM, Narayan MS, Laxman PM, Neelwarne B. Chemical nature stability and bioefficacies of anthocyanins from fruit peel of Syzygium cumini Skeels. Food Chem. 2007;105:619–627. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar A, Naqvi AA, Kahol AP, Tandon S. Composition of leaf oil of Syzygium cumini L, from north India. Indian Perfum. 2004;48:439–441. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vijayanand P, Rao LJM, Narasimham P. Volatile flavour components of Jamun fruit (Syzygium cumini) Flavour Fragr J. 2001;16:47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daulatabad CMJD, Mirajkar AM, Hosamani KM, Mulla GMM. Epoxy and cyclopropenoid fatty acids in Syzygium cuminii seed oil. J Sci Food Agric. 1988;43:91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta RD, Agrawal SK. Chemical examination of the unsaponifiable matter of the seed fat of Syzygium cumini. Sci Cult. 1970;36:298. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadkarni KM. Indian materia medica. Bombay: Popular Prakashan Ltd; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiritikar KR, Basu BD. Indian medicinal plants. Dehradun: International Book Distributors; 1987. pp. 1052–1054. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratsimamanga U. Native plants for our global village. TWAS Newslett. 1998;10:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chandrasekaran M, Venkatesalu V. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of Syzygium jambolanum seeds. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;91:105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jain SK. Dictionary of Indian folk medicine and ethnobotany. New Delhi: Deep Publications Paschim Vihar; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sagrawat H, Mann AS, Kharya MD. Pharmacological potential of Eugenia jambolana: a review. Pharmacogn Mag. 2006;2:96–104. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chirvan-Nia P, Ratsimamanga AR. Regression of cataract and hyperglycemia in diabetic sand rats (Psammomys obesus) having received an extract of Eugenia jambolana Lam. C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci D. 1972;274:254–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sigogneau-Jagodzinski M, Bibal-Prot P, Chanez M, Boiteau P. Contribution to the study of the action of a principle extracted from the myrtle of Madagascar (Eugenia jambolana Myrtaceae) on blood sugar of the normal rat. C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci D. 1967;264:1223–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lal BN, Choudhuri KD. Observations on Momordica charantia Linn, and Eugenia jambolana Lam. as oral antidiabetic remedies. Indian J Med Res. 1968;2:161. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shrotri DS, Kelkar M, Deshmukh VK, Aiman R. Investigations of the hypoglycemic properties of Vinca rosea Cassia auriculata and Eugenia jambolana. Indian J Med Res. 1963;51:464–467. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bose SN, Sepha GC. Clinical observations on the antidiabetic properties of Pterocarpus marsupium and Eugenia jambolana. J Indian Med Assoc. 1956;27:388–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaish SK. Therapeutic uses of Jamun seeds in alloxan diabetes. 1954. p. 230. Proceedings of Indian Science Congress Association.

- 45.Teixeira CC, Knijnik J, Pereira MV, Fuchs FD. The effect of tea prepared from leaves of “jambolao” (Syzygium cumini) on the blood glucose levels of normal rats an exploratory study. 1989. p. 191. Proceedings of the Brazilian-Sino Symposium on Chemistry and Pharmacology of Natural Products, Rio de Janeiro Brazil.

- 46.Schossler DRC, Mazzanti CM, Almeida da Luzi SC, Filappi A, Prestes D, Ferreria da Silveira A, et al. Syzygium cumini and the regeneration of insulin positive cells from the pancreatic duct. Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci. 2004;41:236–239. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Villasenor IM, Lamadrid MRA. Comparative antihyperglycaemic potentials of medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;104:129–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grover JK, Vats V, Rathi SS. Antihyperglycaemic effect of Eugenia jambolana and Tinospora cordifolia in experimental diabetes and their effects on key metabolic enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73:461–470. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vikrant V, Grover JK, Tandon N, Rathi SS, Gupta N. Treatment with extracts of Momordica charantia and Eugenia jambolana prevents hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in fructose fed rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;76:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prince PSM, Kamalakkannan N, Menon VP. Syzigium cumini seed extracts reduce tissue damage in diabetic rat brain. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84:205–209. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00316-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma SB, Nasir A, Prabhu KM, Murthy PS, Dev G. Hypoglycaemic and hypolipidemic effect of ethanolic extract of seeds of Eugenia jambolana in alloxan-induced diabetic rabbits. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;85:201–206. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma SB, Nasir A, Prabhu KM, Murthy PS. Antihyperglycaemic effect of the fruit-pulp of Eugenia jambolana in experimental diabetes mellitus. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;104:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ravi K, Rajasekaran S, Subramanian S. Antihyperlipidemic effect of Eugenia jambolana seed kernel on streptozotocin induced diabetes in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005;43:1433–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banerjee A, Dasgupta N, De B. In vitro study of antioxidant activity of Syzygium cumini fruit. Food Chem. 2005;90:727–733. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sultana B, Anwar F, Przybylski R. Antioxidant activity of phenolic components present in barks of Azadirachta indica, Terminalia arjuna, Acacia nilotica and Eugenia jambolana Lam. trees. Food Chem. 2007;104:1106–1114. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chaudhuri AKN, Pal S, Gomes A, Bhattacharya S. Antiinflammatory and related actions of Syzigium cumini seed extract. Phytother Res. 1990;4:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muruganandan S, Pant S, Srinivasan K, Chandra S, Tandan SK, Lal J, et al. Inhibitory role of Syzygium cumini on autacoid-induced inflammation in rats. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;46:482–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muruganandan S, Srinivasan K, Chandra S, Tandan SK, Lal J, Raviprakash V. Anti-inflammatory activity of Syzygium cumini bark. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:369–375. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chakraborty D, Mahapatra PK, Chaudhuri AKN. A neuropsycho-pharmacological study of Syzigium cumini. Plant Med. 1985;2:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bhuiyan MA, Mia MY, Rashid MA. Antibacterial principles of the seeds of Eugenia jambolana. Bangladesh J Bot. 1996;25:239–241. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shafi PM, Rosamma MK, Jamil K, Reddy PS. Antibacterial activity of Syzygium cumini and Syzygium travancoricum leaf essential oils. Fitoterapia. 2002;73:414–416. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(02)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nascimento GF, Locatelli J, Freitas PC, Silva GL. Antibacterial activity of plant extracts and phytochemicals on antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Braz J Microbiol. 2000;31:247–256. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kusumoto IT, Nakabayashi T, Kida H, Miyashiro H, Hattori H, Namba T, et al. Screening of various plant extracts used in ayurvedic medicine for inhibitory effects on human immunodeficiency virus type I (HIV-I) protease. Phytother Res. 1995;12:488–493. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Braga FG, Bouzada MLM, Fabri RL, Matos MO, Moreira FO, Scio E, et al. Antileishmanial and antifungal activity of plants used in traditional medicine in Brazil. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;111:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jagetia GC, Baliga MS. The evaluation of nitric oxide scavenging activity of certain Indian medicinal plants in vitro a preliminary study. J Med Food. 2004;7:343–348. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2004.7.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Silva DHS, Plaza CV, Bolzani VS, Cavalheiro AJ, Castro-Gamboa I. Antioxidants from fruits and leaves of Eugenia jambolana, an edible Myrtaceae species from Atlantic Forest. Plant Med. 2006;72:1038. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mukherjee PK, Saha K, Murugesan T, Mandal SC, Pal M, Saha BP. Screening of anti-diarrhoeal profile of some plant extracts of a specific region of West Bengal India. J Ethnopharmacol. 1998;60:85–89. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(97)00130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rajasekaran M, Bapna JS, Lakshmanan S, Nair RAG, Veliath AJ, Panchanadam M. Antifertility effect in male rats of oleanolic acid a triterpene from Eugenia jambolana flowers. J Ethnopharmacol. 1988;24:115–121. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(88)90142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Krikorian-Manoukian A, Ratsimamanga AR. Anorexigenic power of a principle extracted from the rotra of Madagascar (Eugenia jambolana Lam.) C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci D. 1967;264:1350–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ramirez RO, Rao CC. The gastroprotective effect of tannins extracted from duhat (Syzygium cumini Skeels) bark on HCl/ethanol induced gastric mucosal injury in Sprague-Dawley rats. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2003;29:253–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.De Lima TCM, Klueger PA, Pereira PA, Macedo-Neto WP, Morato GS, Farias MR. Behavioural effects of crude and semi-purified extracts of Syzygium cumini Linn Skeels. Phytother Res. 1998;12:488–493. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jagetia GC, Baliga MS. Evaluation of the radioprotective effect of the leaf extract of Syzygium cumini (Jamun) in mice exposed to a lethal dose of gamma-irradiation. Nahrung. 2003;47:181–185. doi: 10.1002/food.200390042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jagetia GC, Baliga MS. Syzygium cumini (Jamun) reduces the radiation-induced DNA damage in the cultured human peripheral blood lymphocytes a preliminary study. Toxicol Lett. 2002;132:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(02)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pepato MT, Folgadol VBB, Kettelhut IC, Brunetti IL. Lack of antidiabetic effect of a Eugenia jambolana leaf decoction on rat streptozotocin diabetes. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34:389–395. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2001000300014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sharma HK, Chhangte L, Dolui AK. Traditional medicinal plants in Mizoram India. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:146–161. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jain A, Katewa SS, Galav PK, Sharma P. Medicinal plant diversity of Sitamata wildlife sanctuary Rajasthan India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102:143–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chhetri DR, Parajuli P, Subba GC. Antidiabetic plants used by Sikkim and Darjeeling Himalayan tribes India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;99:199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.de Albuquerque UP, Muniz de Medeiros P, de Almeida AL, Monteiro JM, Machado de Freitas Lins Neto E, Gomes de Melo J, et al. Medicinal plants of the caatinga (semi-arid) vegetation of NE Brazil: a quantitative approach. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;114:325–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ayyanar M. Ethnobotanical wealth of Kani tribe in Tirunelveli hills (Ph.D thesis) University of Madras Chennai India; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Udayan PS, Satheesh G, Tushar KV, Balachandran I. Medicinal plants used by the Malayali tribe of Shevaroy hills Yercaud Salem district Tamil Nadu. Zoos Print J. 2006;21:2223–2224. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nagaraju GJ, Sarita P, Ramana Murty GA, Ravi Kumar M, Reddy BS, Charles MJ, et al. Estimation of trace elements in some anti-diabetic medicinal plants using PIXE technique. Appl Radiat Isot. 2006;64:893–900. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2006.02.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bhandary MJ, Chandrashekar KR, Kaveriappa KM. Medical ethnobotany of the Siddis of Uttara Kannada district Karnataka India. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;47:149–158. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01274-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Teixeira CC, Fuchs FD, Weinert LS, Esteves J. The efficacy of folk medicines in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus results of a randomized controlled trial of Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels. J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;31:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2006.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Natarajan B, Paulsen BS. An ethnopharmacological study from Thane district Maharashtra India traditional knowledge compared with modern biological science. Pharm Biol. 2000;38:139–151. doi: 10.1076/1388-0209(200004)3821-1FT139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]