Abstract

Objective

To isolate and identify Nocardia spp. from soil in different regions of Isfahan province in the center of Iran.

Methods

This study was conducted in 32 districts (16 cities and 16 villages) in Isfahan province during two years. A total of 800 soil samples from these regions were studied by using kanamycin. The isolated Nocardia species were examined by gram and acid-fast staining and were identified biochemically and morphologically. The frequency and distribution of Nocardia spp. were determined in relation to different factors such as soil pH and temperate climate.

Results

From 153 (19.1%) Nocardia isolates identified, Nocardia asteroids (N. asteroids) complex (45.5%) and Nocardia brasiliensis (N. brasiliensis) (24.7%) were the most frequently isolated species, followed by Nocardia otitidiscaviarum (2.2%), Nocardiopsis dassonvillei, Actinomadura actinomadura (each 1.7%) and Nocardia transvalensis (1.1%) and also unknown spp. (23.0%). In this study, most species (54.4%) of Nocardia, especially N. asteroides complex were isolated from soils with pH: 7.01-8, whereas in pH: 8.01-9 more N. brasiliensis was isolated. The most Nocardia spp. was detected from regions with semi-nomadic and temperate climate (41.1%).

Conclusions

N. asteroids complex is more prevalent in Isfahan province and soil can be a potential source of nocardiosis infections. It is to be considering that climate and soil pH are involved in the frequency and diversity of aerobic Actinomycetes.

Keywords: Nocardia, Nocardiosis, Actinomycetes, Soil microbiology, Isfahan, Iran, Nocardia asteroids, Climate

1. Introduction

Nocardia species are aerobic Actinomycetes, gram-positive, non-spore, filamentous, branching, obligatory aerobic and relatively slow-growing bacteria[1]. So far, more than 50 species in the genus Nocardia are described among which Nocardia asteroids (N. asteroids) complex, Nocardia brasiliensis (N. brasiliensis), Nocardia transvalensis (N. transvalensis), Nocardia otitidiscaviarum (N. otitidiscaviarum), Nocardia farcinica and Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis are more pathogenic in humans[2]. These organisms are found in sludge, soil, contaminated soils water, plants, spoiled material and plant and cause opportunistic infections in humans and animals[3]–[10].

Increase in the infections caused by these organisms, with different clinical forms of systemic and disseminated forms of nocardiosis in transplant recipients, tuberculosis, liver cirrhosis, cancer, diabetes, AIDS and patients under treatment with immunosuppressive drugs and broad spectrum antibiotics in the world, reveals more importance of isolation and identification of these agents[2],[11]–[24]. Various studies have shown that identification and isolation of these agents in soil of different areas help to diagnose nocardiosis[1].

Aerobic Actinomycetes are found in soils in different parts of the world. However, according to various factors such as environment and ecological factors like temperature, humidity, vegetation zone, etc., their abundance is variable in different regions of the world. Nocardiosis is sporadic in Iran, but in other countries it is more prevalent. In USA, 500–1 000 new case of nocardiosis was annually reported[1],[3],[4],[25].

Due to the climate and vegetation diversity in Isfahan province, which is one of the major tourist cities in the world, the present study was carried out with the goals of isolation and identification of different species of Nocardia in different regions and investigating the effect of environmental factors such as soil pH and type of climate on the frequency of these microorganisms in soil.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study site

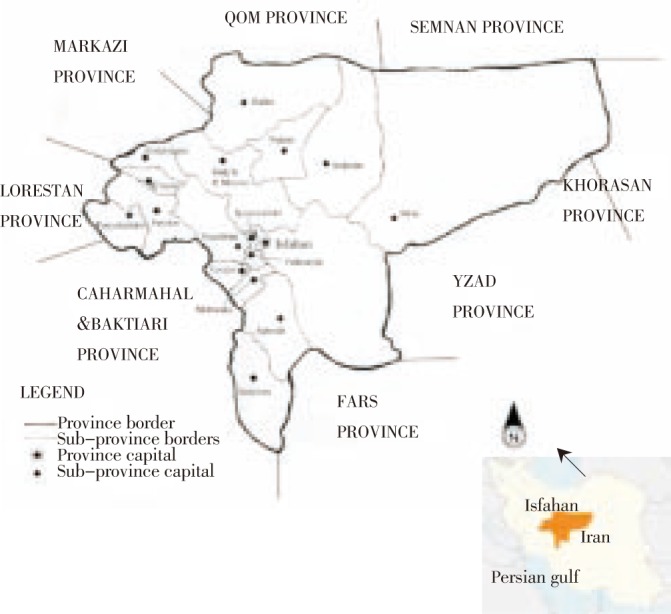

This study was done in Isfahan province (32°39′N, 51°40′E, with an area of 107 027 km2) in the center of Iran, during 2007–2008.

2.2. Sampling

A total of 800 soil samples were collected randomly from 800 different locations in 16 townships (including 16 cities and 16 villages) in Isfahan province. Fifty soil samples from each township (including 30 samples from central city and 20 samples from selected villages) were collected (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The map of soil sampling location in Isfahan province.

Sampling was carried out in winter and work on the samples lasted for 18 months. Sampling locations in cities included squares, boulevards, sidewalk, area offices, coastal and forest parks, rivers, waterfall and samples were collected in villages from corral livestock and domestic animals, nests, farm land, fruit gardens, garden houses, etc. Soil samples to the amount of 100–200 g for each sample were collected from superficial layer with depth not exceeding 2–5 cm. The samples were placed in sterile polyethylene bags, transported immediately to the laboratory and were stored at low temperature (4 °C) until tested. The pH of the samples was measured immediately in a 1:5 soil/deionized water suspension (w/v) using a pH meter according to a previous study[26].

Studied townships based on air temperature and humidity that in the sampling phase were measured. Considering the geographical situation, townships were divided into 3 groups including townships with cold and semi-wet climate, semi-nomadic climate and desert climate (Table 1).

Table 1. Separation of studied townships according to the type of climate.

| Climate | Townships |

| Cold and semi-wet | Khansar, Semirom, Feraidan, Feraidoonshahr, Golpayegan, Natanz |

| Semi-nomadic | Borkharomeimeh, Shahreza, Flavarjan, Lenjan, Mobarekeh |

| Desert | Ardestan, Khomainishahr, Kashan, Naiin, Najafabad |

In this study, three methods were evaluated during a pre-test. Initially, the method of glass rods dipped in paraffin in 30 soil samples from Falavarjan city was used, but due to high bacterial contamination, it did not achieve satisfactory results and only two positive samples with bacterial contamination were found. Then, two soil samples positive by dilution method with chloramphenicol and tetracycline antibiotics were evaluated. In this method, no Nocardia spp. and other Actinomycetes were isolated and only bacterial contamination was observed. Then, to solve this problem, the third method that used the medium containing kanamycin on these two samples was utilized in which satisfactory results were obtained.

2.3. Isolation method

For preparing suspensions, 3–5 g of soil samples were added to tubes containing 10 mL sterile saline and then tubes were shaken for 3 min. Then the suspension was incubated for 15 min and thereafter, 2–5 mL of the supernatant solution was transferred to another sterile tube by sterile pipette.

Streptomycin, chloramphenicol and antibiotic solutions (2 mg/mL) were added to half the volume of supernatant solution and the mixture was incubated for half an hour after being stirred up. Then after being shaken again, one drop (0.05 mL) of a brain-heart infusion (BHI) agar medium (Merck, Germany), containing cycloheximide (0.5 g/L) and kanamycin (25 mg/L) was added to the tube immediately, and then the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 2 weeks[14]. During this period, the wrinkled colonies of red, orange, yellow, and white to cream colors suspicious of Nocardia and other aerobic Actinomycetes were considered and cover slip-buried methods were used. If delicate and branched filaments which are the characteristics of Actinomycetes were seen, they were isolated by Sabouraud dextrose agar medium in tubes. Then by using Kinyoun staining, conventional biochemical tests and physiological criteria such as the capability to degrade the organic compounds such as tyrosine, casein, hypoxanthine, xanthine and starch as substrates, as well as growth in 4% gelatin medium, were studied in order to reach a possible classification to the species level[1].

3. Results

Among the 800 soil samples, 153 (19.1%) were positive for Nocardia spp. and other aerobic Actinomycetes. A total of 178 isolates of Nocardia spp. and other aerobic Actinomycetes were recognized. They belonged to 6 species of 3 genus as follows: N. asteroides complex (45.5%), N. brasiliensis (24.7%), N. otitidiscaviarum (2.2%), Nocardiopsis dassonvieli (N. dassonvieli) and Actinomadura madurae (A. madurae) (1.7%), N. transvalensis (1.1%) and unknown spp. (23.0%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of Nocardia spp. and other aerobic Actinomycetes isolated from soils of 16 townships in the province of Isfahan, Iran.

| Parameters | Townships |

Total | % Frquency | ||||||||||||||||

| Ard | Bor | Fer | Fla | Fsh | Gol | Kas | Kha | Kho | Len | Mob | Nai | Naj | Nat | Sem | Sha | ||||

| No. of samples examined | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 800 | ||

| Positive samples | 4 (8) | 2 (4) | 13 (26) | 21 (42) | 6 (12) | 3 (6) | 7 (14) | 10 (20) | 8 (16) | 16 (32) | 9 (18) | 13 (26) | 12 (24) | 9 (18) | 8 (16) | 12 (24) | 153 (19.1) | ||

| Species isolated | N. asteroides complex | 3 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 81 | 45.5 |

| N. brasiliensis | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 44 | 24.7 | |

| N. otitidiscaviarum | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2.2 | |

| N. transvalensis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1.1 | |

| A. madurae | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.7 | |

| N. dassonvieli | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1.7 | |

| Unknown spp. | 2 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 41 | 23 | |

| Total | 6 | 2 | 17 | 24 | 9 | 3 | 8 | 11 | 9 | 19 | 10 | 13 | 14 | 11 | 8 | 14 | 178 | 100 | |

Ard: Ardestan; Bor: Borkharomeimea; Fer: Feraidan; Fla: Flavarjan; Fsh: Feraidoonshahr; Gol: Golpayegan; Kas: Kashan; Kha: Khansar; Kho: Khomainishahr; Len: Lenjan; Mob: Mobarekea; Nai: Naiin; Naj: Najafabad; Nat: Natanz; Sem: Semirom; Sha: Shahreza.

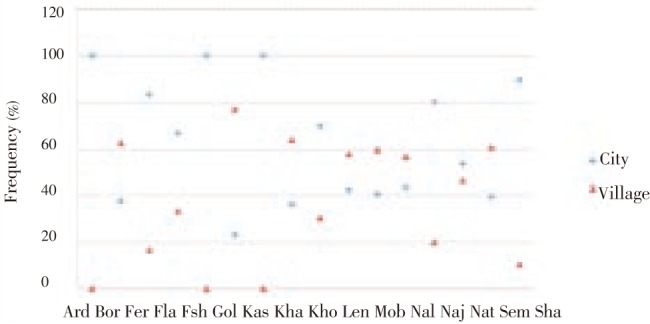

In this study, in most cities, N. asteroids complex was the dominant species. Moreover, more Nocardia spp. and other aerobic Actinomycetes were isolated from urban areas than rural regions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Frequency of Nocardia spp. and other aerobic Actinomycetes isolated from soils of urban and rural regions from 16 townships in the province of Isfahan, Iran.

Ard: Ardestan; Bor: Borkharomeimea; Fer: Feraidan; Fla: Flavarjan; Fsh: Feraidoonshahr; Gol: Golpayegan; Kas: Kashan; Kha: Khansar; Kho: Khomainishahr; Len: Lenjan; Mob: Mobarekea; Nai: Naiin; Naj: Najafabad; Nat: Natanz; Sem: Semirom; Sha: Shahreza.

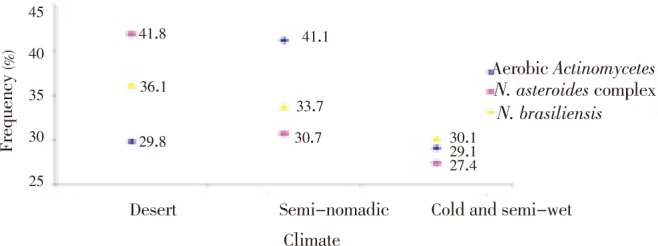

In the present study, most Nocardia spp. and other aerobic Actinomycetes were detected from regions with semi-nomadic and temperate climate (41.1%). Also most N. asteroides complexes (30.7%) were detected from regions with this type of climate (Figure 3). In addition, N. brasiliensis (36.1%) were most detected from regions with desert climate (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Frequency of Nocardia spp. and aerobic Actinomycetes isolated from soils of 16 townships in the province of Isfahan, Iran at different climate.

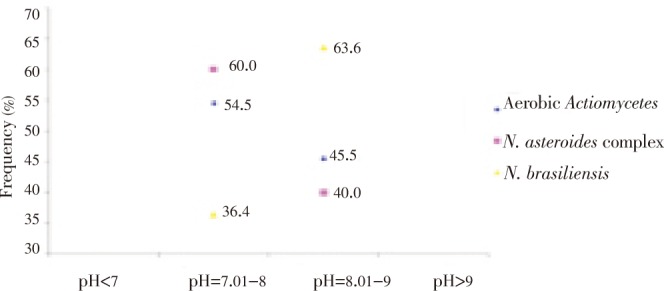

Figure 4 showed the distribution of the Nocardia spp. and other aerobic Actinomycetes in relation to soil pH. We found 54.5% Nocardia spp. and other aerobic Actinomycetes from the soil samples with pH: 7.01–8 and 45.5% from pH: 8.01–9. We did not find aerobic Actinomycetes from the soil samples with pH: 6–7.

Figure 4. Frequency of Nocardia spp. and aerobic Actinomycetes isolated from soils of 16 townships in the province Isfahan, Iran at pH different values.

In the present study, most N. asteroides complex species (60.0%) were isolated from the soil samples with pH: 7.01–8. In contrast, most N. brasiliensis species (63.6%) were isolated from the soil samples with pH: 8.01–9 (Figure 4).

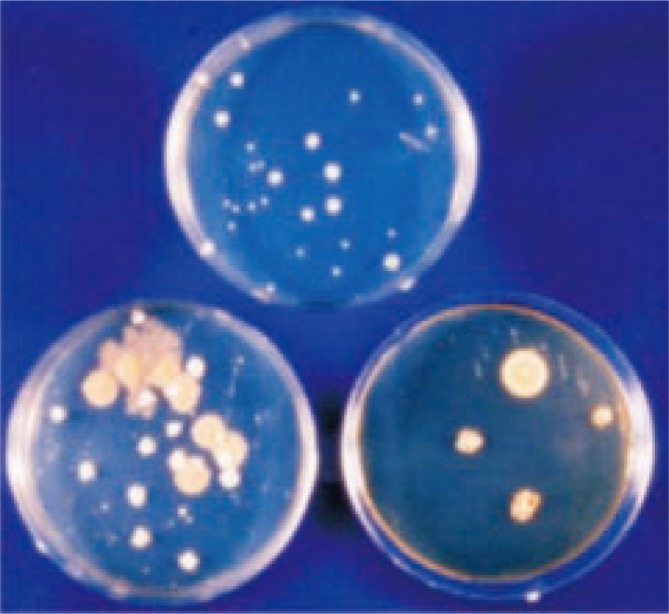

Figure 5 showed isolated Nocardia spp. from BHI agar medium containing cycloheximide (0.5 g/L) and kanamycin (25 mg/L), which was incubated at 37 °C for 7–10 day.

Figure 5. Isolated Nocardia spp. from BHI agar medium containing cycloheximide (0.5 g/L) and kanamycin (25 mg/L).

4. Discussion

In this study, isolation of different species of Nocardia spp. from soil in different regions of Isfahan, Iran and the effect of environmental factors such as soil pH and types of climate on frequency of these bacteria in soil were examined. In the present study, BHI agar medium containing two antibiotics (kanamycin and cycloheximide) were used and it was shown that the growth of Nocardia and Actinomadura was stimulated by kanamycin and in most cases in positive samples, only one colony or purified species of Nocardia was observed without microbial contamination. For the first time, Vetlugina et al used kanamycin for the isolation of Nocardia spp. from soil[14]. In this research, paraffin bait method was not applied because of bacterial contamination and some species of Nocardia and Actinomycetes do not grow on paraffin substrate.

In our study, Nocardia prevalence in soil was 16.4%. The frequency of pathogenic Nocardia species acquired from soil samples in different regions of the world has been reported to be 5%–50%[27]–[30]. In other survey in Iran the isolation rate of Nocardia from soil was reported to be 40.6%[25]. Differences observed in these studies could be due to type of studied soil and methods used[29].

In this study, the dominant species was N. asteroides complex. These results are similar with studies of Khan et al[28], Van Gelderen et al[30], and Ajello et al[31].

Studies in Iran show that like other parts of the world, the dominant agent of nocardiosis is N. asteroides complex. Nocardiosis in Iran and other parts of the world in clinical forms of pulmonary, sinusitis and mycetoma has been reported[32]–[39]. Also, like the study performed by Stapleton et al, in this study it was found that the rate of isolation of Nocardia spp. in semi-desert climate to colder regions is higher[40].

In this study, most species (54.4%) of Nocardia, especially N. asteroides complex was isolated from soils with pH: 7.01–8, whereas in pH: 8.01–9 more N. brasiliensis was isolated. It is to be considering that climate and soil pH are involved in the frequency and diversity of aerobic Actinomycetes. There is no previous report about relationship between pH and diversity of Nocardia in soil.

In this study, Streptomyces were not isolated, which was probably due to the following reasons: 1) according to Rippon[41], species of Streptomyces have been observed in soils with pH less than 6.5, whereas in this study, about 90% of soil samples were with pH>7; 2) another possible reason can be the sensitivity of Streptomyces to the amount of kanamycin used.

In general, soil pH and type of climate were probably involved in the rate of Nocardia spp. isolated from soil. Also kanamycin in culture medium is useful in isolation of Nocardia. It is also necessary to mention that this technique was used for the isolation of aerobic Actinomycets from soil samples for the first time in Iran.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Shidfar MR, Geramishoar M, Professor Kordbachea P, Professor Zaini F and Dr. Mirhendi SH in Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Isfahan Research State for their cooperation and valuable comments.

Footnotes

Foundation Project: This work was financially supported by Teheran University of Medical Sciences (grant No. TUMS/HF-2446).

Conflict of interest statement: We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Brown-Elliott BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, Wallace RJ. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259–282. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.259-282.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan DC, Chapman SW. Bacteria that masquerade as fungi: ctinomycosis/nocardia. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:216–221. doi: 10.1513/pats.200907-077AL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arifuzzaman M, Khatun MR, Rahman H. Isolation and screening of actinomycetes from Sundarbans soil for antibacterial activity. Afr J Biotechnol. 2010;9:4615–4619. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sazak A, Sahin N, Camas M. Nocardia goodfellowii sp. nov. and Nocardia thraciensis sp. nov., isolated from soil in Turkey. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011 doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.031559-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trichet E, Cohen-Bacrie S, Conrath J, Drancourt M, Hoffart L. Nocardia transvalensis keratitis: an emerging pathology among travelers returning from Asia. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:296. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castelli JB, Siciliano RF, Abdala E, Aiello VD. Infectious endocarditis caused by Nocardia sp.: histological morphology as a guide for the specific diagnosis. Braz J Infect Dis. 2011;15:384–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arends JE, Stemerding AM, Vorst SP, Neeling AJ, Weersink AJ. First report of a brain abscess caused by Nocardia veterana. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:4364–4365. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01062-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masaki T, Ohkusu K, Ezaki T, Miyamoto H. Nocardia elegans infection involving purulent arthritis in humans. J Infect Chemother. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10156-011-0311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sahu SK, Sharma S, Das S. Nocardia scleritis-clinical presentation and management: a report of three cases and review of literature. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s12348-011-0043-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amatya R, Koirala R, Khanal B, Dhakal SS. Nocardia brasiliensis primary pulmonary nocardiosis with subcutaneous involvement in an immunocompetent patient. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29(1):68–70. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.76530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardak E, Yigla M, Berger G, Sprecher H, Oren I. Clinical spectrum and outcome of Nocardia infection: experience of 15-year period from a single tertiary medical center. Am J Med Sci. 2011 doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31822cb5dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ambrosioni J, Lew D, Garbino J. Nocardiosis: updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. 2010;38:89–97. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-9193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dodiuk-Gad R, Cohen E, Ziv M, Goldstein LH, Chazan B, Shafer J, et al. et al. Cutaneous nocardiosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1380–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinaud C, Verdonk C, Bousquet A, Macnab C, Vaylet F, Soler C, et al. et al. Isolation of Nocardia beijingensis from a pulmonary abscess reveals human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2748–2750. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00613-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogade S, Metgud SC, Swoorooparani Actinomycetes mycetoma. J Lab Physicians. 2011;3:43–45. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.78564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minero MV, Marín M, Cercenado E, Rabadán PM, Bouza E, Muñoz P. Nocardiosis at the turn of the century. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009;88:250–261. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181afa1c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínez R, Reyes S, Menéndez R. Pulmonary nocardiosis: risk factors, clinical features, diagnosis and prognosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008;14(3):219–227. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3282f85dd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaswan KK, Vanikar AV, Feroz A, Patel HV, Gumber M, Trivedi HL. Nocardia infection in a renal transplant recipient. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2011;22:1203–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad N, Suresh JK, Gupta A, Prasad KN, Sharma RK. Nocardia asteroides peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients: case report and review of the literature. Indian J Nephrol. 2011;21:276–279. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.78070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al Akhrass F, Hachem R, Mohamed JA, Tarrand J, Kontoyiannis DP, Chandra J, et al. et al. Central venous catheter-associated Nocardia bacteremia in cancer patients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1651–1658. doi: 10.3201/eid1709.101810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alnaum HM, Elhassan MM, Mustafa FY, Hamid ME. Prevalence of Nocardia species among HIV-positive patients with suspected tuberculosis. Trop Dr. 2011;41:224–226. doi: 10.1258/td.2011.110107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu X, Han F, Wu J, He Q, Peng W, Wang Y, et al. et al. Nocardia infection in kidney transplant recipients: case report and analysis of 66 published cases. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13:385–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanioka K, Nagao M, Yamamoto M, Matsumura Y, Tabu H, Matsushima A, et al. et al. Disseminated Nocardia farcinica infection in a patient with myasthenia gravis successfully treated by linezolid: a case report and literature review. J Infect Chemother. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10156-011-0315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohmori S, Kobayashi M, Yaguchi T, Nakamura M. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis caused by Nocardia beijingensis in an immunocompromised patient with chemotherapy for advanced prostate cancer. J Dermatol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aghamirian MR, Ghiasian SA. Isolation and characterization of medically important aerobic Actinomycetes in soil of Iran (2006–2007) Open Microbiol J. 2009;3:53–57. doi: 10.2174/1874285800903010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Musallam AA. Distribution of keratinophilic for sponsoring the color photography fungi in animals folds in Kuwait. Mycopathologia. 1990;112:65–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00436500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vetlugina LA, Adiiatova ZhF, Khozhamuratova SSh, Rymzhanova ZA, Trenozhnikova LP, Kopytina MN. Isolation of Actinomycetales from the soil of Kazakhestan on selective media with antibiotics. Antibiot Khimioter. 1990;35:3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan ZU, Neil L, Chandy R, Chugh TD, Al-Sayer H, Provost F, et al. et al. Nocardia asteroides in the soil of Kuwait. Mycopathologia. 1997;137:159–163. doi: 10.1023/a:1006857801113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goel S, Kanta S. Prevalence of Nocardia species in the soil of Patiala area. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1993;36:53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Gelderen DKA, Runco DL, Salim R. Natural occurrence of Nocardia in soil of Tucuman: physiological characteristics. Mycopathologia. 1987;99:15–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00436675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ajello G, Brown J, Mahgoub ES, Ajello L. A note on the isolation of pathogenic aerobic actinomycetes from Sudanese soil. Curr Microbiol. 1979;2:25–26. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agterof MJ, van der Bruggen T, Tersmette M, ter Borg EJ, van den Bosch JM, Biesma DH. Nocardiosis: a case series and a mini review of clinical and microbiological features. Neth J Med. 2007;65:199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shojaei H, Hashemi A, Heidarieh P, Eshraghi S, Khosravi AR, Daei Naser A. Clinical isolation of Nocardia cyriacigeorgica from patients with various clinical manifestations, the first report from Iran. Med Mycol J. 2011;52:39–43. doi: 10.3314/jjmm.52.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zarei MA, Zarrin M. Mycetomas in Iran: a review article. Mycopathologia. 2008;165:135–141. doi: 10.1007/s11046-007-9066-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shamsadini S, Shamsi MS, Sadre ES, Vahidreza S. Report of two cases of mycetoma in the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13:1219–1222. doi: 10.26719/2007.13.5.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asilian A, Yoosefi A, Faghihi G. Cutaneous and pulmonary nocardiosis in pemphigus vulgaris: a rare complication of immunosuppressive therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1204–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu BQ, Zhang TT, Zhu JX, Liu H, Huang J, Zhang WX. Pulmonary nocardiosis in immunocompromised host: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2009;32:593–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carison H. Mycetoma (Madura foot) JAAPA. 2011;24:79. doi: 10.1097/01720610-201105000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blackmon KN, Ravenel JG, Gomez JM, Ciolino J, Wray DW. Pulmonary nocardiosis: computed tomography features at diagnosis. J Thorac Imaging. 2011;26(3):224–229. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181f45dd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stapleton F, Keay LJ, Sanfilippo PG, Katiyar S, Edwards KP, Naduvilath T. Relationship between climate, disease severity, and causative organism for contact lens-associated microbial keratitis in Australia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:690–698. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rippon JW. Medical mycology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Sauders Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]