Abstract

The protein family (Pfam) PF04536 is a broadly conserved domain family of unknown function (DUF477), with more than 1,350 members in prokaryotic and eukaryotic proteins. High-quality NMR structures of the N-terminal domain comprising residues 41–180 of the 684-residue protein CG2496 from Corynebacterium glutamicum and the N-terminal domain comprising residues 35–182 of the 435-residue protein PG0361 from Porphyromonas gingivalis both exhibit an α/β fold comprised of a four-stranded β-sheet, three α-helices packed against one side of the sheet, and a fourth α-helix attached to the other side. In spite of low sequence similarity (18%) assessed by structure-based sequence alignment, the two structures are globally quite similar. However, moderate structural differences are observed for the relative orientation of two of the four helices. Comparison with known protein structures reveals that the α/β architecture of CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182) has previously not been characterized. Moreover, calculation of surface charge potential and identification of surface clefts indicate that the two domains very likely have different functions.

Keywords: CG2496, PG0361, CgR26A, PgR37A, PF04536, DUF477, Structural genomics

Introduction

684-residue protein CG2496 from Corynebacterium glutamicum (UniProt accession number Q6M3G5) and 435-residue protein PG0361 from Porphyromonas gingivalis (Q7MX54) contain N-terminally located domains, which belong to the Pfam [1] protein family PF04536 of unknown function (DUF477) (Fig. S1). This broadly conserved protein domain family contains currently 1,351 members from a wide range of different bacteria, eukaryotic organisms, and remarkably also one archaebacterium (crenarchaeota). The N-terminal domains CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182), which exhibit very low ClustalW [2] pairwise sequence identity (<20%), were selected as targets of the Protein Structure Initiative and assigned to the Northeast Structural Genomics consortium (NESG; http://www.nesg.org) for structure determination (NESG Target IDs CgR26A and PgR37A, respectively), as part of the a cooperative intercenter effort aimed at providing structural coverage of large, uncharacterized protein domain families [3]. Initial structural representatives of such families exhibit high modeling leverage [4], expand our understanding of protein evolution [5], and generally expand our knowledge of fundamental relationships between protein sequences, three-dimensional structure, and protein function. The solution NMR structures of CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182) presented here are the first atomic resolution structures for domains of Pfam family PF04536.

Methods

CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182) were cloned, expressed, and purified following protocols [6–8] established by the NESG (see Supplementary Material for details; http://www.nmr2.buffalo.edu/nesg.wiki). The proteins included short C-terminal hexaHis tags (LEHHHHHH). The corresponding pET expression vectors (NESG CgR26A-41-180-21.3 and PgR37A-35-182-21.12), have been deposited in the PSI Materials Repository (http://psimr.asu.edu/). Protein samples were prepared at ∼0.9 mM concentration in 90% H2O/10% D2O, in a buffer containing 20 mM MES, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 5 mM CaCl2, 50 μM DSS, 0.02% NaN3 at pH 6.5. The [5% 13C; U-15N]-labeled samples enabled stereospecific assignment of the methyl groups of Val and Leu residues [9]. Isotropic overall rotational correlation times of about 9 ns were inferred from average 15N spin relaxation times for both CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182) (Supplementary Material, http://www.nmr2.buffalo.edu/nesg.wiki), indicating that both protein domains are monomeric in solution. This finding was confirmed by analytical gel-filtration with static light scattering detection (Supplementary Figs. S2, S3).

NMR data were acquired at 25°C on Varian INOVA 600 and 750 MHz, and Bruker AVANCE 800 and 900 MHz spectrometers, each equipped with a cryogenic 1H{13C,15N} probe. Total NMR measurement time for CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182) was 150 h each. Nearly complete sequence-specific 1H, 15N and 13C resonance assignments (Table 1; Supplementary Figs. S4, S5) were obtained from conventional triple-resonance NMR experiments (Supplementary Material) using the programs AutoAssign 2.3.0 [10, 11] and PINE [12], followed by manual assignment of side-chain resonances. Assignments were validated using the AVS software suite [13]. Chemical shifts, NOESY peak lists, and time domain NMR data have been deposited in the BioMagResBank (accession numbers 16569 and 16810 for CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182), respectively).

Table 1. CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182) structure statistics.

| CG2496(41–180) | PG0361(35–182) | |

|---|---|---|

| Completeness of resonance assignmentsa (%) | ||

| Backbone/Side-chain | 100.0/99.7 | 98.1/100.0 |

| Completeness of stereospecific assignmentsb (%) | ||

| Val & Leu isopropyl/βCH2/αCH2 of Gly | 100/35/50 | 100/25/30 |

| Conformation-restricting distance constraintsc | ||

| Intraresidue (i = j) | 432 | 593 |

| Sequential (|i ‒ j| = 1) | 567 | 894 |

| Medium range (1 < |i ‒ j| < 5) | 579 | 1,012 |

| Long range (|i ‒ j| ≥ 5) | 1,067 | 1,453 |

| Total | 2,645 | 3,952 |

| Dihedral angle constraints (φ/ψ) | 73/73 | 77/77 |

| Distance constraints per residue (of those, long-range) | 24.7 (9.4) | 27.0 (9.6) |

| CYANA target function (Å2) | 0.45 ± 0.16 | 1.85 ± 0.16 |

| Average number of distance constraint violations per conformer | ||

| 0.2‒0.5 Å | 1.0 | 5.6 |

| >0.5 Å | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Average number of dihedral angle constraint violations per conformer | ||

| >10° | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Average RMSD from mean coordinates (Å) | ||

| Backbone heavy atoms (all heavy atoms)d | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.9) |

| Backbone heavy atoms (all heavy atoms)e | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.9) |

| Heavy atoms of molecular coref | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Global quality scoresc (raw/Z-score) | ||

| PROCHECK [32] G-factor(φ and ψ) | 0.08/0.63 | −0.04/0.16 |

| PROCHECK [32] G-factor (all dihedral angles) | 0.07/0.41 | 0.02/0.12 |

| MOLPROBITY [33] clash score | 19.81/−1.87 | 23.77/−2.55 |

| Verify3D [34] | 0.47/0.16 | 0.48/0.32 |

| ProsaII [35] | 0.98/1.36 | 0.68/0.12 |

| RPF scores [23] | ||

| Recall/Precision/F-measure | 0.98/0.93/0.96 | 0.97/0.92/0.95 |

| DP-score | 0.90 | 0.85 |

| MOLPROBITY [33] Ramachandran summarye (%) | ||

| Most favored regions | 98.9 | 97.2 |

| Allowed regions | 1.0 | 2.5 |

| Disallowed regions | 0.1 | 0.3 |

Calculated with the AVS suite [13] excluding low complexity regions (residues 172–180 in CG2496), as well as C-terminal tags, N-terminal and Lys and Arg side chain amino groups, hydroxyl of Ser, Thr and Tyr, carboxyls of Asp and Glu, and non-protonated aromatic carbons

Relative to pairs with non-degenerate chemical shifts

Calculated with PSVS 1.4 [22]

Regular secondary structure elements: residues 57–59, 66–82, 86–91, 100–110, 116–122, 127–132, 138–153, 157–169 in CG2496(41–180) and 54–56, 63–79, 83–89, 97–108, 118–124, 129–134, 144–161, 164–182 in PG0361(35–182)

Ordered residues: 56–60, 63–93, 98–111, 115–168 in CG2496(41–180) and 37–45, 54–92, 95–108, 118–134, 137–181 PG0361(35–182)

Residues 56–61, 63–72, 74–76, 79–83, 85–95, 98–100, 102–104, 106–111, 115–123, 127–128, 130–131, 134, 136–137, 139, 141–144, 146–149, 151–153, 155–158, 160–165, 167–168 in CG2496(41–180) and 36, 37, 39, 42, 43, 45, 53–55, 58, 60, 61, 64, 68, 69, 73, 75, 76, 78, 80–90, 92, 95–97, 100–102, 104, 105, 107, 108, 119–125, 130–134, 138, 141–143, 146–148, 150, 151, 155–159, 161, 163–165, 168, 169, 172–176, 178, 179 in PG0361(35–182). Includes best-defined side chains

Structure calculations were performed using standardized methods of the NESG consortium [14, 15] and consensus analysis of automated NOESY (mixing time 70 ms) cross peak assignments provided by the programs CYANA[ 16, 17] and AutoStructure 2.2.1 [18] based on 1H–1H NOE-derived upper limit distance constraints, and backbone dihedral angle constraints derived from chemical shifts using the program TALOS+ [19] for residues located in well-defined regular structure elements. Stereospecific assignments of methylene protons were performed with the GLOMSA module of CYANA and the final structure calculation was performed with CYANA followed by refinement of selected conformers in an ‘explicit water bath’ [20] using the program CNS 1.2 [21]. Validation of the resulting 20 refined conformers for each domain structure was performed with the Protein Structure Validation Software (PSVS) server 1.3 [22] and the agreement of structures and NOESY peak lists was verified using the AutoStructure/RPF 2.2.1 package [23].

Results and discussion

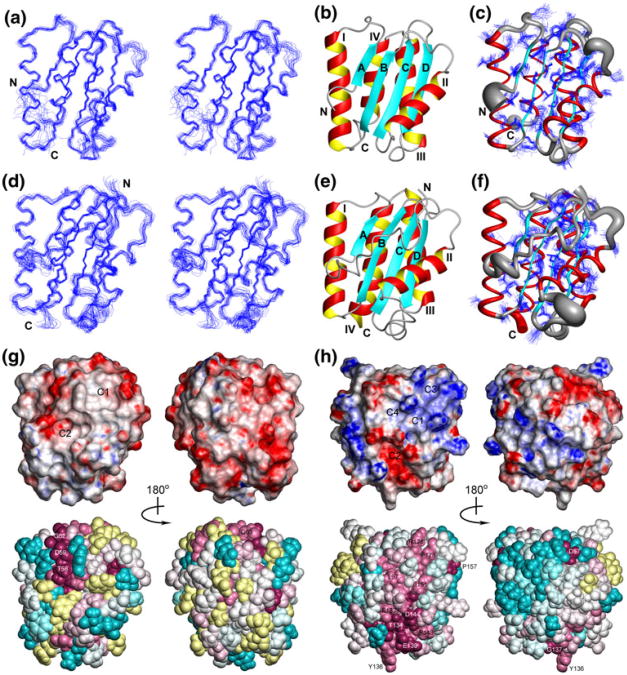

We obtained high-quality (Table 1) NMR structures of CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182) (Fig. 1) and their coordinates were deposited in the Protein Data Bank [24] on 10/19/2009 (accession code 2KPT) and 03/31/2010 (accession code 2KW7), respectively. Both structures exhibit an α/β-fold (Fig. 1b,e) consisting of four α-helices and a four-stranded β-sheet with the topology A(↑)B(↑)C(↑)D(↓). α-Helices I, III and IV are packed against one side of the β-sheet, while helix II is located on the opposite side. The locations of regular secondary structure elements are: β-strands A (residues 57–59 in CG2496/54–56 in PG0361), B (86–91/83–89), C (116–122/118–124) and D (127–132/129–134), and α-helices I (66–82/63–79), II (100–111/97–108), III (138–153/144–161) and IV (157–169/164–182).

Fig. 1.

a Stereoview of the 20 conformers representing the solution structure of CG2496(41–180) obtained after superposition of the Cα atoms of the regular secondary structure elements for minimal RMSD. Residues 41–52 and 172–180 of the disordered N- and C-terminal polypeptide segments were omitted for clarity, and the termini are labeled as “N” and “C”. b Ribbon diagram of residues 53–171 of the lowest-energy conformer of CG2496(41–180): α-helices are shown in red and yellow, β-strands are depicted in cyan, other polypeptide segments are in gray. c Sausage representation of backbone and superposition of the conformation of the best defined side chains (Table 1). A spline curve was drawn through the mean positions of Cα atoms of residues 53–171 with the thickness proportional to the mean global displacement of Cα atoms in the 20 conformers superimposed in (a). d Same as a for PG0361(35–182) with residues 35–182 shown. e Same as b for PG0361(35–182) with residues 35–182 shown. f Same as (c) for PG0361(35–182) with residues 35–182 shown. g Surface and space-filling representations of the lowest-energy conformer of CG2496(41–180) colored according to the electrostatic potential and the degree of residue conservation, respectively. The default ConSurf color scheme for residue conservation is employed: burgundy for the strongest conservation, cyan for the highest variability, and yellow for residues with insufficient data. Only residues 53–171 are shown with the flexible terminal segments excluded. The structures shown on the left have the same orientation as Fig. 1, and those on the right are rotated by 180° around the vertical axis. Surface clefts identified by Mark-Us/SCREEN are labeled as C1 and C2. h Same as g for the lowest-energy conformer of PG0361(35–182) with residues 35–182 shown, The structures shown on the left are rotated around the vertical axis by 90° relative to the orientation in (d–f), and those on the right are rotated by a further 180°. Surface clefts identified by Mark-Us/SCREEN are labeled as C1, C2, C3 and C4

In spite of the very low sequence identity (18% inferred from structure, Fig. S1c), the three-dimensional structures of PG0361(35–182) and CG2496(41–180) are quite similar: the root mean square deviation (RMSD) calculated for the mean coordinates of the backbone heavy atoms N, Cα and C′ of regular secondary structure elements is 2.2 Å. Furthermore, α-helices III and IV exhibit the largest structural differences in terms of length and packing against the remainder of the protein molecule, and Pro 157 introduces a kink in α-helix III of PG0361(35–182) that is absent in CG2496(41–180). As a result, the corresponding RMSD value calculated for only for the β-sheet and α-helices I and II is much lower, that is, 1.0 Å. A rather distant homology is reflected by the fact that 25% of the residues of the molecular core are conserved between PG0361(35–182) and CG2496(41–180) (Fig. S1c).

A search of the PDB database for similar structures using the program DALI [25] identifies the C-terminal domain of alanyl-tRNA synthetase (named “C-Ala domain” in the following) from Aquifex aeolicus (PDB code 3G98) as the only highly significant hit (other hits had Z-scores < ∼6) for both CG2496(41–180) (best match with chain B of 3G98: Z-score 8.4, RMSD of Cα atoms = 2.3 Å for 85 aligned residues with 8% sequence identity) and PG0361(35–182) (best match with chain A of 3G98: Z-score 6.5, RMSD of Cα atoms = 2.5 Å for 89 aligned residues and 4% sequence identity). However, the comparably small number of aligned residues indicates that structural similarity with C-Ala domain is limited to segments of the protein molecules. This is confirmed by visual inspection (Fig. S6): C-Ala domain contains a β-sheet with topology A(↓)B(↑)C(↑)D(↓)E(↑)F(↓), but only β-strands B-D and α-helices II-IV align structurally with corresponding regular structure elements in CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182). Moreover, the short β-strand A is arranged in opposite direction in C-Ala domain, α-helix I is absent, and the short polypeptide segment connecting α-helices III and IV in both CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182) is replaced by the antiparallel β-strands E and F. Furthermore, the functionally important Arg 840 residue predicted to interact with the elbow of tRNAAla, which is located in the β-strand F [26], is not present in CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182). Hence, CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182) are quite likely functionally not similar to the C-Ala domain; the observed partial structural similarity may have emerged from convergent evolution. This view is further supported by the fact that the full length proteins CG2496 and PG0361 are certainly not tRNA synthetases, but have entirely different functions: they are predicted to contain (1) transmembrane segments (Figs. S7–S10) and (2) N-terminal signal sequences for translocation in the extracellular and periplasmic space (Figs. S7–S12). Taken together, the search for structurally similar proteins reveals that CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182) exhibit a novel α/β architecture. So far, these structures have not yet yielded insights into their molecular functions.

Calculation of electrostatic surface potentials and identification of surface clefts, which are possibly of functional importance [27, 28], indicates that CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182) actually have different functions in the context of the full-length proteins. CG2496(41–180) features a mostly negative electrostatic surface potential and analysis using Mark-Us/SCREEN2 [27, 29] reveals two adjacent surface clefts C1 and C2 (Fig. 1g) located between the β-sheet and α-helix II (C1, 33 Å2 surface area, formed by Thr 58, Phe 88, Val 90, Trp 103, Ala 107, Asn 111 and Ile 188; C2, 25 Å2 surface area, Tyr 60, Leu 92, Ser 93, Ser 94, Phe95, Asp 96 and Trp 103). In contrast, PG0361(35–182) exhibits a mixed charge surface potential and four clefts C1-C4 (Fig. 1h) in rather different locations (C1, 77 Å2 surface area, Leu 64, Glu 65, Arg 96, Val 97, Arg 98, Ser 115, Ile 118, His 119, Ile 123; C2, 51 Å2 surface area, Glu 65, Leu 69, Lys 81, Arg 98, Glu 100, Thr 101, Gly 102, Glu 106, Asp 111; C3, 34 Å2 surface area, Arg 95, Arg 96, Ile 123, Phe 126, Arg 127; C4, 26 Å2 surface area, Ile 59, Gly 60, Asp 61, Ala 62, Leu 64, Gln 94, Arg 96). The only common feature appears to be that cavities C2 are negatively charged in both proteins, and that they exhibit the highest degrees of conservation within their non-overlapping modeling families (see below).

Different functions for CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182) are also suggested by the genomic context of the full-length proteins. Operon prediction [30] using the MicrobesOnline server (http://www.microbesonline.org) indicates that the gene encoding protein CG2496 is transcribed individually. In contrast, the gene of PG0361 is part of an operon also containing the genes pyrB and pyrI which encode subunits of an aspartate carbamoyl transferase catalyzing the first step of de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis.

Finally, identification of modeling families as was described previously [4, 31] reveals that the novel structural leverage, i.e., the number of protein structures that can be reliably modeled using the experimental structures presented here, is 7 and 368 for CG2496(41–180) and PG0361(35–182), respectively. However, structural leverage is dependent on the methods used for modeling [4, 31], and as homology modeling methods advance the leverage of these structures will also expand. Thus, considering that currently PF04536 contains 1145 non-redundant sequences, the two NMR structures presented here provide high leverage and conservatively ∼33% structural coverage for the very large Pfam family PF04536.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Lee, K. Hamilton, D. Wang, W. A. Buchwald, C. Ciccosanti, H. Janjua, R. Nair and S. Bhattacharya for helpful discussions and technical support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant number: U54 GM094597 (T.S. and G.T.M.). When NMR data acquisition took place, Prof. T. Szyperski was a member of the New York Structural Biology Center. The Center is a STAR center supported by the New York State Office of Science, Technology, and Academic Research. 900 MHz spectrometer was purchased with the funds from NIH, USA, the Keck Foundation, New York State, and the NYC Economic Development Corporation.

Abbreviations

- C-Ala domain

C-terminal domain of alanyl-tRNA Synthetase

- DSS

4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonate sodium salt

- DTT

Dithiothreitol

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- NESG

Northeast structural genomics consortium

- NOE

Nuclear overhauser effect

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- RMSD

Root mean square deviation

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material: The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10969-011-9122-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Alexander Eletsky, Department of Chemistry, The State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA; Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA.

Thomas B. Acton, Center for Advanced Biotechnology and Medicine and Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA; Department of Biochemistry, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, UMDNJ, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA; Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA

Rong Xiao, Center for Advanced Biotechnology and Medicine and Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA; Department of Biochemistry, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, UMDNJ, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA; Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA.

John K. Everett, Center for Advanced Biotechnology and Medicine and Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA; Department of Biochemistry, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, UMDNJ, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA; Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA

Gaetano T. Montelione, Center for Advanced Biotechnology and Medicine and Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA; Department of Biochemistry, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, UMDNJ, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA; Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA

Thomas Szyperski, Email: szypersk@buffalo.edu, Department of Chemistry, The State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA; Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA.

References

- 1.Finn RD, Mistry J, Schuster-Bockler B, Griffiths-Jones S, Hollich V, Lassmann T, Moxon S, Marshall M, Khanna A, Durbin R, Eddy SR, Sonnhammer ELL, Bateman A. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D247–D251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins DG, Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ. Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dessailly BH, Nair R, Jaroszewski L, Fajardo JE, Kouranov A, Lee D, Fiser A, Godzik A, Rost B, Orengo C. PSI-2: structural genomics to cover protein domain family space. Structure. 2009;17:869–881. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu JF, Montelione GT, Rost B. Novel leverage of structural genomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:850–853. doi: 10.1038/nbt0807-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murzin AG, Brenner SE, Hubbard T, Chothia C. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:537–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acton TB, Gunsalus KC, Xiao R, Ma LC, Aramini J, Baran MC, Chiang YW, Climent T, Cooper B, Denissova NG, Douglas SM, Everett JK, Ho CK, Macapagal D, Rajan PK, Shastry R, Shih LY, Swapna GVT, Wilson M, Wu M, Gerstein M, Inouye M, Hunt JF, Montelione GT. Nuclear magnetic resonance of biological macromolecules, Part C. In: James TL, editor. Methods in enzymology. Vol. 394. Elsevier; San Diego: 2005. pp. 210–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao R, Anderson S, Aramini J, Belote R, Buchwald WA, Ciccosanti C, Conover K, Everett JK, Hamilton K, Huang YJ, Janjua H, Jiang M, Kornhaber GJ, Lee DY, Locke JY, Ma LC, Maglaqui M, Mao L, Mitra S, Patel D, Rossi P, Sahdev S, Sharma S, Shastry R, Swapna GVT, Tong SN, Wang DY, Wang HA, Zhao L, Montelione GT, Acton TB. The high-throughput protein sample production platform of the Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium. J Struct Biol. 2010;172:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acton TB, Xiao R, Anderson S, Aramini J, Buchwald WA, Ciccosanti C, Conover K, Everett J, Hamilton K, Huang YJ, Janjua H, Kornhaber G, Lau J, Lee DY, Liu GH, Maglaqui M, Ma LC, Mao L, Patel D, Rossi P, Sahdev S, Shastry R, Swapna GVT, Tang YF, Tong SC, Wang DY, Wang H, Zhao L, Montelione GT. Fragment-based drug design: tools, practical approaches, and examples. In: Kuo LC, editor. Methods in enzymology. Vol. 493. 2011. pp. 21–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neri D, Szyperski T, Otting G, Senn H, Wuthrich K. Stereospecific nuclear magnetic resonance assignments of the methyl groups of valine and leucine in the DNA-binding domain of the 434 repressor by biosynthetically directed fractional 13C labeling. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7510–7516. doi: 10.1021/bi00445a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moseley HNB, Monleon D, Montelione GT. Nuclear magnetic resonance of biological macromolecules, Pt B. In: James TL, Dötsch V, Schmitz U, editors. Methods in enzymology. Vol. 339. Elsevier; San Diego: 2001. pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimmerman DE, Kulikowski CA, Huang YP, Feng WQ, Tashiro M, Shimotakahara S, Chien CY, Powers R, Montelione GT. Automated analysis of protein NMR assignments using methods from artificial intelligence. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:592–610. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bahrami A, Assadi AH, Markley JL, Eghbalnia HR. Probabilistic interaction network of evidence algorithm and its application to complete labeling of peak lists from protein NMR spectroscopy. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moseley HNB, Sahota G, Montelione GT. Assignment validation software suite for the evaluation and presentation of protein resonance assignment data. J Biomol NMR. 2004;28:341–355. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000015420.44364.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang YPJ, Moseley HNB, Baran MC, Arrowsmith C, Powers R, Tejero R, Szyperski T, Montelione GT. Nuclear magnetic resonance of biological macromolecules, Part C. In: James TL, editor. Methods in enzymology. Vol. 394. Elsevier; San Diego: 2005. pp. 111–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu GH, Shen Y, Atreya HS, Parish D, Shao Y, Sukumaran DK, Xiao R, Yee A, Lemak A, Bhattacharya A, Acton TA, Arrow-smith CH, Montelione GT, Szyperski T. NMR data collection and analysis protocol for high-throughput protein structure determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10487–10492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504338102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guntert P, Mumenthaler C, Wuthrich K. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program DYANA. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:283–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrmann T, Guntert P, Wuthrich K. Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE assignment using the new software CANDID and the torsion angle dynamics algorithm DYANA. J Mol Biol. 2002;319:209–227. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang YJ, Tejero R, Powers R, Montelione GT. A topology-constrained distance network algorithm for protein structure determination from NOESY data. Proteins. 2006;62:587–603. doi: 10.1002/prot.20820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linge JP, Williams MA, Spronk C, Bonvin A, Nilges M. Refinement of protein structures in explicit solvent. Proteins. 2003;50:496–506. doi: 10.1002/prot.10299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macro-molecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattacharya A, Tejero R, Montelione GT. Evaluating protein structures determined by structural genomics consortia. Proteins. 2007;66:778–795. doi: 10.1002/prot.21165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang YJ, Powers R, Montelione GT. Protein NMR recall, precision, and F-measure scores (RPF scores): structure quality assessment measures based on information retrieval statistics. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1665–1674. doi: 10.1021/ja047109h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holm L, Sander C. Dali: a network tool for protein structure comparison. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:478–480. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schimmel P, Guo M, Chong YE, Beebe K, Shapiro R, Yang XL. The C-Ala domain brings together editing and aminoacylation functions on one tRNA. Science. 2009;325:744–747. doi: 10.1126/science.1174343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honig B, Nayal M. On the nature of cavities on protein surfaces: application to the identification of drug-binding sites. Proteins. 2006;63:892–906. doi: 10.1002/prot.20897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laskowski RA. Surfnet: a program for visualizing molecular-surfaces, cavities, and intermolecular interactions. J Mol Graphics. 1995;13:323. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(95)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petrey D, Fischer M, Honig B. Structural relationships among proteins with different global topologies and their implications for function annotation strategies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17377–17382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907971106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alm EJ, Price MN, Huang KH, Arkin AP. A novel method for accurate operon predictions in all sequenced prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:880–892. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nair R, Liu J, Soong TT, Acton TB, Everett JK, Kouranov A, Fiser A, Godzik A, Jaroszewski L, Orengo C, Montelione GT, Rost B. Structural genomics is the largest contributor of novel structural leverage. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2009;10:181–191. doi: 10.1007/s10969-008-9055-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laskowski RA, Rullmann JAC, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. Aqua and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen VB, Arendall WB, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luthy R, Bowie JU, Eisenberg D. Assessment of protein models with 3-dimensional profiles. Nature. 1992;356:83–85. doi: 10.1038/356083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sippl MJ. Recognition of errors in 3-dimensional structures of proteins. Proteins. 1993;17:355–362. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.