Abstract

Background

Kidney cancer accounts for over 4000 UK deaths annually, and is one of the cancer sites with a poor mortality record compared with Europe.

Aim

To identify and quantify all clinical features of kidney cancer in primary care.

Design

Case-control study, using General Practice Research Database records.

Method

A total of 3149 patients aged ≥40 years, diagnosed with kidney cancer between 2000 and 2009, and 14 091 age, sex and practice-matched controls, were selected. Clinical features associated with kidney cancer were identified, and analysed using conditional logistic regression. Positive predictive values for features of kidney cancer were estimated.

Results

Cases consulted more frequently than controls in the year before diagnosis: median 16 consultations (interquartile range 10–25) versus 8 (4–15): P<0.001. Fifteen features were independently associated with kidney cancer: visible haematuria, odds ratio 37 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 28 to 49), abdominal pain 2.8 (95% CI = 2.4 to 3.4), microcytosis 2.6 (95% CI = 1.9 to 3.4), raised inflammatory markers 2.4 (95% CI = 2.1 to 2.8), thrombocytosis 2.2 (95% CI = 1.7 to 2.7), low haemoglobin 1.9 (95% CI = 1.6 to 2.2), urinary tract infection 1.8 (95% CI = 1.5 to 2.1), nausea 1.8 (95% CI = 1.4 to 2.3), raised creatinine 1.7 (95% CI = 1.5 to 2.0), leukocytosis 1.5 (95% CI = 1.2 to 1.9), fatigue 1.5 (95% CI = 1.2 to 1.9), constipation 1.4 (95% CI = 1.1 to 1.7), back pain 1.4 (95% CI = 1.2 to 1.7), abnormal liver function 1.3 (95% CI = 1.2 to 1.5), and raised blood sugar 1.2 (95% CI = 1.1 to 1.4). The positive predictive value for visible haematuria in patients aged ≥60 years was 1.0% (95% CI = 0.8 to 1.3).

Conclusion

Visible haematuria is the commonest and most powerful single predictor of kidney cancer, and the risk rises when additional symptoms are present. When considered alongside the risk of bladder cancer, the overall risk of urinary tract cancer from haematuria warrants referral.

Keywords: diagnosis, haematuria, kidney cancer, primary health care

INTRODUCTION

Kidney cancer is the 14th most common cancer worldwide, and accounts for 2–3% of new cancer diagnoses.1 It is associated with cigarette smoking and obesity, and has a male to female ratio of 8:5.2 The incidence rises with age: 74% of UK diagnoses are made in the ≥60 years age group, with 64 years being the average age at diagnosis. Renal cell cancer accounts for >80% of kidney cancers, the remainder being transitional cell cancers of the renal pelvis (7–8%) and the childhood Wilm’s tumour (1%).1,3,4 Five-year survival for patients with a localised tumour is 85%, dropping to between 35 and 60% after regional spread has occurred and below 10% after metastasis.5 Emergency presentations occur in 24% of cases, slightly above the UK norm for all cancers, and have a higher mortality.6 Mortality from kidney cancer increased until 2005, when it levelled off.7 No reliable screening test is available, nor is it likely to be in the foreseeable future. The UK is one of several countries with a gatekeeper healthcare system, where GPs control access to secondary care. Countries with a gatekeeper system have shown to have significantly lower 1-year cancer survival rates.8

Diagnostic research in this field has — until this article — examined kidney cancer along with other urological cancers, but not separately. Furthermore, as bladder cancer is more common, its symptoms will have contributed in a large part to the findings. Moreover, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines combine bladder and renal cancers in their recommendations.9 However, the studies upon which these guidelines were based were largely conducted in secondary care, using patients already selected for investigation, so are typically at a later stage of their disease. There have been no primary care reports examining multiple clinical features of urological cancer, although four primary care studies have examined haematuria, merging kidney, bladder, and sometimes prostate cancers. In one study of patients referred to an open access haematuria clinic, renal cancers were found in six (1.7%) of the 363 in the cohort.10 A similar Belgian study reported ‘other’ urological cancers (not bladder) in 39 patients. The positive predictive value (PPV) of visible haematuria was 2.0% for urological cancer.11 A cohort study using UK electronic records estimated PPVs for haematuria for combined urological cancer of males: 5.5%, (95% confidence interval [CI] = 4.9 to 6.1) and females 2.5% (95% CI = 2.1 to 3.0).12 No analysis was available for individual cancer sites. In a final study assessing predictors of renal tract cancer, the following symptoms were identified: haematuria, abdominal pain, weight loss, anaemia, and appetite loss (the latter in females only).13 No PPVs were calculated. Again, the results were not separated by cancer site. It is not known if the symptoms of bladder and kidney cancer differ. If they do, this could have clinical importance, as the first choice of investigation for possible kidney cancer is ultrasound, whereas for bladder cancer it is cystoscopy: in most urological clinics both are performed. Ultrasound is generally available in primary care so, in theory at least, GPs could test for possible kidney cancer without referral.

How this fits in

The clinical features of kidney cancer have not been studied separately in primary care. The study found seven symptoms to be associated with the cancer. All the positive predictive values for these symptoms were very small, apart from haematuria. However, only 18% of patients with kidney cancer had haematuria recorded in their records, so a policy of investigation based solely on that symptom will miss most cancers.

This study aimed to identify and quantify the early clinical features (symptoms, diseases and abnormal investigations) of kidney cancer in primary care, with the intention that this will inform the selection of patients for definitive investigation.

METHOD

This was a matched case-control study using patient records in the UK’s General Practice Research Database (GPRD), which contains anonymised patient records from nearly 600 general practices across the UK. Data are recorded for all primary care consultations and investigation results. The GPRD applies stringent data quality levels on their practices.14,15

Cases and controls

Cases had a record of one of 22 GPRD kidney cancer codes (based on Read Codes and linked to ICD-10 classifications; available from authors) between January 2000 and December 2009 inclusive. All were aged ≥40 years with a minimum of 1 year of data before diagnosis. All cancer sites were studied for patients aged ≥40 years as cancers in the under 40s are rare and often atypical. Up to five controls per case were matched to cases by sex, general practice, and age (within 1 year). There is no ‘standard’ case-control ratio for studies like this, and this study restricted to five by resources, still provided ample power (see below). The first cancer code was taken to be the date of diagnosis, or index date.14,15 The controls’ index dates matched that of their case. Exclusion criteria were: metastatic cancer to the kidney from a non-kidney primary, diagnosis before 2000, or no consultations in the year before diagnosis. In preparing the dataset the GPRD inadvertently added a bladder cancer code to the dataset. These cases were identified and removed.

Selection of investigations and symptom variables

A list of features potentially associated with kidney cancer was generated from three sources: a traditional literature review using PubMed and EBSCO, patient reported symptoms and clinical knowledge. Self-reported features were taken from several online kidney cancer support organisations and chat rooms and identified through internet searches using search terms like ‘kidney cancer’, ‘kidney cancer symptoms’, and ‘early signs/indications/symptoms kidney cancer’. Visible and non-visible haematuria were studied separately. The single word ‘haematuria’ was assumed to be visible haematuria, with only descriptions using the term ‘microscopic’ or ‘trace’ assigned to non-visible haematuria. Over 1800 GPRD codes were compiled for the putative features of kidney cancer from the GPRD master list of over 100 000 codes. Occurrences of these features were identified in the year before the index date. Repeated consultations for the same complaint were also identified. Additionally, records of fractures were compiled to identify any recording bias (assuming that the fracture rate would be approximately equal between cases and controls).14,15 Any feature reported in fewer than 5% of cases or controls was excluded. Abnormal investigation results were defined as the patient having a test value falling outside their local laboratory’s normal range. Patients with a normal laboratory result were grouped with those who had not been tested. The raised inflammatory markers variable was a composite of any of abnormal erythrocyte sedimentation rate, plasma viscosity, or C-reactive protein; similarly abnormal liver function tests reflected a raised value of any of the hepatic enzymes reported by each laboratory.

Analysis and statistical methods

Analysis followed the protocol used in previous studies.14–17 The main method was conditional logistic regression, performed in three stages. First, univariable analysis was conducted on the putative features. These were retained if they had a P-value of ≤0.1, and were grouped for the first multivariable analysis, with retention requiring a P-value ≤0.05. A final multivariable model was compiled from the surviving features of the previous stages. This used a P-value threshold of 0.01. All excluded variables were checked against the final model. Clinically plausible interaction terms were added to the final model and retained if their P-value was also ≤0.01.

Positive predictive values (PPVs) were produced for all features shown to be independently associated with kidney cancer. This was repeated for pairs of symptoms and for second attendances with the same symptom. Bayes’ theorem was used to calculate the PPVs (prior odds x likelihood ratio = posterior odds). The prior odds used were the age-specific national incidence of kidney cancer for 2008, expressed as odds. To enable the calculation of PPVs for the consulting population, the proportion of the control population who had not consulted in the year before diagnosis was estimated: 1483 (9.5%) of 15 574 eligible controls had not consulted. PPVs were therefore divided by 0.905 to give the figure for the consulting population.

Power calculations were used rather than sample size calculations 3000 cases and 15 000 controls (the estimates initially provided by the GPRD) provided >98% power (5% two-sided alpha) to detect a change in a rare variable from 1% in cases and 2% of controls. For a commoner variable, the study had >97% power to detect a change in prevalence of 20% in cases to 17% in controls. Data analysis was conducted using Stata software (version 11).

RESULTS

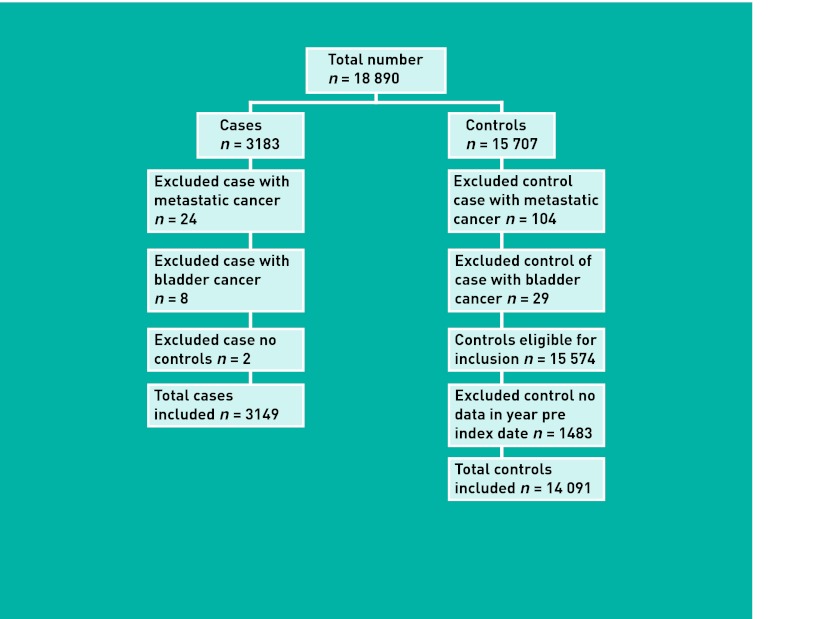

The GPRD provided 18 890 patients (3183 cases; 15 707 controls). Application of the exclusion criteria is shown in Figure 1, leading to a final number of 17 240 (3149 cases; 14 091 controls).

Figure 1.

Application of exclusion criteria.

Patient demographic and consultation information is given in Table 1. Cases consulted significantly more frequently than controls in the year before diagnosis (P ≤0.001; ranksum test).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and consultation rates in the year before diagnosis

| Cases | Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 1930) | Female (n = 1219) | Total (n = 3149) | Male (n = 8429) | Female (n = 5662) | Total (n = 14091) | |

| Median (IQR) age at diagnosis, years | 68 (60–76) | 71 (62–79) | 69 (61–77) | 69 (61–76) | 71 (62–79) | 70 (61–77) |

| Median (IQR) number of consultations | 16 (10–24) | 17 (11–25) | 16 (10–25) | 8 (4–14) | 9 (4–16) | 8 (4–15) |

IQR = interquartile range.

Clinical features

Twenty-four symptoms and twenty-two abnormal test results were considered initially. Ten symptom and eleven abnormal test variables were present in at least 5% of cases. Just over 1% of cases in this study had a record of non-visible haematuria. Features associated with kidney cancer in univariable and multivariable analysis are shown in Table 2. All variables in the final multivariable model had a P-value <0.001. No interaction terms were found.

Table 2.

Clinical features of kidney cancer (all ages)

| Feature | Cases, n (%) n = 3149 | Controls, n (%) n = 14091 | Likelihood ratioa (95% CI) | Odds ratio in multivariable analysis b (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||||

| Visible haematuria | 558 (18) | 97 (1) | 26 (21 to 32) | 37 (28 to 49) |

| Back pain | 341 (11) | 901 (6) | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.7) |

| Abdominal pain | 350 (11) | 514 (4) | 3.1 (2.7 to 3.5) | 2.8 (2.4 to 3.4) |

| Fatigue | 210 (7) | 405 (3) | 2.3 (2.0 to 2.7) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) |

| Constipation | 194 (6) | 420 (3) | 2.1 (1.8 to 2.4) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) |

| Nausea | 171 (5) | 263 (2) | 2.9 (2.4 to 3.5) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.3) |

|

| ||||

| Diseases | ||||

| Lower urinary tract infection | 339 (11) | 608 (4) | 2.5 (2.2 to 2.8) | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.1) |

|

| ||||

| Investigations | ||||

| Raised inflammatory markers | 783 (25) | 993 (7) | 3.5 (3.2 to 3.8) | 2.4 (2.1 to 2.8) |

| Low haemoglobin | 738 (23) | 968 (7) | 3.4 (3.1 to 3.7) | 1.9 (1.6 to 2.2) |

| Raised liver function test | 654(21) | 1526 (11) | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.1) | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.5) |

| Raised creatinine | 565 (18) | 1095 (8) | 2.3 (2.1 to 2.5) | 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) |

| Raised blood sugar | 485 (15) | 1378 (10) | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.7) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) |

| Thrombocytosis | 348 (11) | 251 (2) | 6.2 (5.3 to 7.3) | 2.2 (1.7 to 2.7) |

| Leukocytosis | 304 (10) | 330 (2) | 4.1 (3.5 to 4.8) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) |

| Microcytosis | 233 (7) | 158 (1) | 6.6 (5.4 to 8.1) | 2.6 (1.9 to 3.4) |

The univariate likelihood ratio, showing the likelihood of having a specific feature in a patient with kidney cancer, compared with the likelihood of having it in a patient without cancer.

In multivariate conditional logistic regression, containing all 15 variables

From the 3149 cases, 2334 (74%) had at least one of the final model features from Table 2 recorded. The proportion of patients with a fracture did not differ between cases and controls (P<0.094).

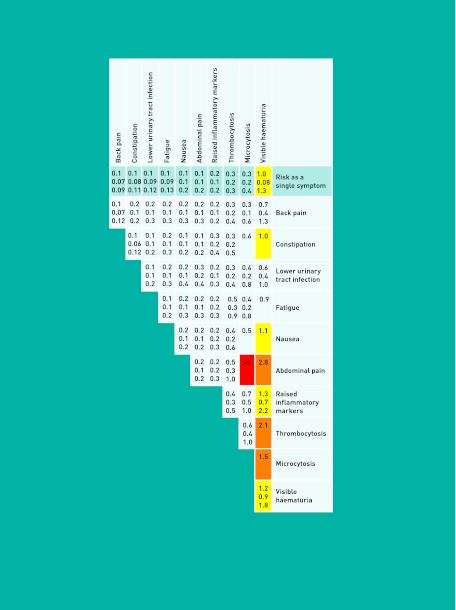

Positive predictive values

Figure 2 shows the PPVs for individual, combined, and repeat features, for patients aged ≥60 years. The top line represents risk for each single feature; below is the risk for combined and repeated features. The greater the number and darkness of the shading shown, the higher the associated risk was.

Figure 2.

Positive predictive values for kidney cancer in patients ≥60 years of age, for individual, paired and repeated features.

The likelihood ratios were similar between patients aged 40–59 and ≥60 years. The resulting PPVs were approximately twice as high in the over 60s group. The one exception was visible haematuria, which showed a higher association to kidney cancer in the under 60s group (40–59 likelihood ratio [LR]: 55.6; ≥60 LR: 22.1) The PPV of visible haematuria in the 40–59 years age group was 0.7% (95% CI = 0.4 to 1.3).

DISCUSSION

Summary

This study is the first to identify multiple clinical features of kidney cancer in primary care, and quantify them. Seven symptoms, one disease and eight abnormal investigation results were associated with the cancer. The highest single risk was for visible haematuria, being 1.0% for patients aged ≥60 years. Risk increased slightly for repeat symptoms, and when combined with abnormal investigations or abdominal pain. The remaining features were associated with relatively low risk.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this study are its large size, its primary care setting and its sole focus on kidney cancer. The use of GPRD data allowed the study to access thousands of cases from UK general practices. The GPRD is the UK’s largest computerised patient record database with an established reputation for data quality and diagnostic validity.18,19 Using it ensured patient representativeness across the UK, good power and generalisable results. The large size also enabled sub-analyses by age and sex. Additionally, the start of this study coincides with the period of time when the automatic transmission of laboratory data began. As a consequence, recording error was largely eliminated. Apart from size, another major strength of this study is its setting. The use of primary care data is vital if results are to feed back into future referral selection processes. This is the main clinical problem: deciding who warrants referral, especially in the patient without alarm symptoms. It was particularly useful, therefore, to analyse all clinical features, rather than just haematuria. This allowed for new features to be identified. Additionally, the use of online support group websites allowed us to investigate patient reported symptoms absent from the scientific literature so far. Therefore, it is unlikely that any relevant feature was omitted from this study’s list.

The nature of this study meant that it was reliant on the accuracy of GP data recording. The GPRD contains many codes, some of which overlap. There will have been variation in GP selection of codes for recording of symptoms, although there is usually a dominant code used by most GPs for that symptom. There will also be some under-recording of symptoms. This is only a problem if present particularly in cases or controls. This was not seen for fractures. If under-recording is approximately equal in cases and controls, the likelihood ratios and PPVs will still be correct. It is possible that pertinent features may have been recorded in the ‘free text’ section which is the area where GPs can amplify their clinical record without having to use pre-supplied codes. The GPRD does not release the free-text routinely; for fear that it may lead to de-anonymisation. Nonetheless, a recent study on free-text indicated a high concordance between free-text data and diagnostic coding.20 The case-control design of this study meant that prior odds could not be calculated from within the study. Instead, the prior odds of cancer from registry data were estimated. The size of the national registries will have provided a more accurate estimate than any cohort study could give.

Comparison with existing literature

Almost 30% of renal cancer patients consult their GP three or more times before diagnosis, a marker that has been used as a proxy for delays in diagnosis.21,22 The current study fits with this finding, in that cases consulted twice as often as controls. Higher consultations may not represent delays. Indeed they could, in part at least, represent initial investigation for possible urine infection, followed by review. Such clinical practice is good medicine, although there is a fine dividing line between appropriate in-house testing and creating delays. However, existing research has shown that mortality rates worsen in countries where access to specialists is guarded by primary care physicians.8

Previous primary care research has never studied kidney cancer alone, merging it with bladder and sometimes prostate, ureteric or urethral cancers. The main reported symptom for these cancers is haematuria. The PPV of 1.0%, with narrow confidence intervals, was lower than previous reports, although most of these had small sample sizes, and wide confidence intervals.11 The closest comparator also used the GPRD, and found PPVs approximately four to five times higher than this study.12 This can easily be explained by the Jones study also merging bladder and kidney cancer (plus urethra, although it is very rare).12 A study of bladder cancer alone yielded a PPV for haematuria of 2.6%, which when added to the 1.0% for kidney cancer gives very similar figures to the Jones study.14 A final primary care study highlighted the importance of clinical features other than haematuria in urological cancers.13 Symptoms identified for both sexes were: haematuria, abdominal pain, weight loss and anaemia, although combinations of symptoms were not reported. An increased risk when combined with certain abnormal investigations was also found: raised inflammatory markers, thrombocytosis, or microcytosis. Thrombocytosis in primary care cancer diagnosis may be important. An association between thrombocytosis and kidney, pancreatic, and lung cancers was also found.15,23

Implications for practice

There has been a progressive shift towards primary care investigation of possible cancer. Chest X-ray and colonoscopy, for lung and colorectal cancers, have been available for many years without specialist input. Ca125 and transvaginal ultrasound are now available for possible ovarian cancer, and open-access MRI brain was launched in 2012.24 Abdominal ultrasound is widely available, and this is the main initial investigation for possible kidney cancers. It was hoped to identify symptom complexes other than haematuria, which could have allowed GPs to order an ultrasound. Instead, the results of this study are dominated by haematuria. An ultrasound alone would be insufficient to rule out cancer, as it is not sufficiently accurate in bladder cancer diagnosis. Thus for investigation of haematuria, the twin approach of ultrasound and cystoscopy is still appropriate.

Visible haematuria is the highest individual risk factor for developing kidney cancer. If kidney cancer were the only cancer of interest, then it is questionable if the PPV would warrant testing of all patients with haematuria. However, when the possibility of bladder cancer is added, haematuria per se warrants testing. There are subtle differences between kidney and bladder cancer symptoms.14 Negative results on both tests will be required to rule out cancer with confidence. The bladder and kidney findings will be merged, and the results fed into the current revision of the NICE guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution to the research presented in this paper made by the Discovery Programme Steering Committee comprising: Roger Jones (chair); Jonathan Banks; Alison Clutterbuck; Jon Emery; Joanne Hartland; Sandra Hollinghurst; Maire Justice; Jenny Knowles; Helen Morris; Tim Peters; Greg Rubin.

Funding

This study was funded by the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme, RP-PG-0608-10045. William Hamilton was part-funded by a NIHR post-doctoral fellowship.

Ethical approval

Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (protocol 09-110).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

William Hamilton is clinical lead on the ongoing revision of the NICE guidance on investigation of suspected cancer. Other than this, no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Cancer Research UK . Kidney cancer: UK incidence statistics. Cancer Research UK; 2012. http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/kidney/incidence/#geog (accessed 20 Feb 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergström A, Hsieh CC, Lindblad P, et al. Obesity and renal cell cancer — a quantitative review. Br J Cancer. 2001;85(7):984–990. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macmillan . Types of kidney cancer. Macmillan Cancer Support; 2012. http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Cancerinformation/Cancertypes/Kidney/Aboutkidneycancer/Typesofkidneycancer.aspx (accessed 20 Feb 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow WH, Dong LM, Devesa SS. Epidemiology and risk factors for kidney cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7(5):245–257. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merck manuals . Kidney cancer. Whitehouse Station, NJ, US: Merck and Co; 2007. http://www.merckmanuals.com/home/kidney_and_urinary_tract_disorders/cancers_of_the_kidney_and_urinary_tract/kidney_cancer.html (accessed 20 Feb 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Cancer Intelligence Network . Routes to diagnosis — NCIN data briefing. London: NCIN; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Research UK . Mortality statistics. Kidney cancer — UK mortality statistics. Cancer Research UK; 2012. http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/kidney/mortality/ (accessed 20 Feb 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vedsted P, Olesen F. Are the serious problems in cancer survival partly rooted in gatekeeper principles? Br J Gen Pract. 2011 doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X588484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence . Referral Guidelines for suspected cancer. London: NICE; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Summerton N, Mann S, Rigby AS, et al. Patients with new onset haematuria: assessing the discriminant value of clinical information in relation to urological malignancies. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(477):284–289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruyninckx R, Buntinx F, Aertgeerts B, Van Casteren V. The diagnostic value of macroscopic haematuria for the diagnosis of urological cancer in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(486):31–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones R, Latinovic R, Charlton J, Gulliford MC. Alarm symptoms in early diagnosis of cancer in primary care: cohort study using General Practice Research Database. BMJ. 2007;334(7602):1040. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39171.637106.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Coupland, Identifying patients with suspected renal tract cancer in primary care: derivation and validation of an algorithm. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X636074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shephard EA, Stapley S, Neal RD, et al. Clinical features of bladder cancer in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X654560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stapley S, Peters TJ, Neal RD, et al. The risk of pancreatic cancer in symptomatic patients in primary care: a large case-control study using electronic records. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(12):940–1944. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton W, Kernick D. Clinical features of primary brain tumours: a case-control study using electronic primary care records. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(542):695–699. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton W, Round A, Sharp D, Peters TJ. Clinical features of colorectal cancer before diagnosis: a population-based case-control study. Br J Cancer. 2005;93(4):399–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan NF, Harrison SE, Rose PW. Validity of diagnostic coding within the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2010 doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X483562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thiru K, Hassey A, Sullivan F. Systematic review of scope and quality of electronic patient record data in primary care. BMJ. 2003;326(7398):1070. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7398.1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tate AR, Martin AG, Ali A, Cassell JA. Using free text information to explore how and when GPs code a diagnosis of ovarian cancer: an observational study using primary care records of patients with ovarian cancer. BMJ Open. 2011;1(1):e000025. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2010-000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyratzopoulos G, Neal RD, Barbiere JM, et al. Variation in number of general practitioner consultations before hospital referral for cancer: findings from the 2010 National Cancer Patient Experience Survey in England. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(4):353–365. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton W. Diagnosis: cancer diagnosis in UK primary care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(5):251–252. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton W, Peters TJ, Round A, Sharp D. What are the clinical features of lung cancer before the diagnosis is made? A population based case-control study. Thorax. 2005;60(12):1059–1065. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.045880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Health . Direct access to diagnostic tests for cancer: best practice referral pathways for general practitioners. London: DoH; 2012. [Google Scholar]